Chapter 41 NURSING MANAGEMENT: upper gastrointestinal problems

1. Describe the aetiology, complications, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of nausea and vomiting.

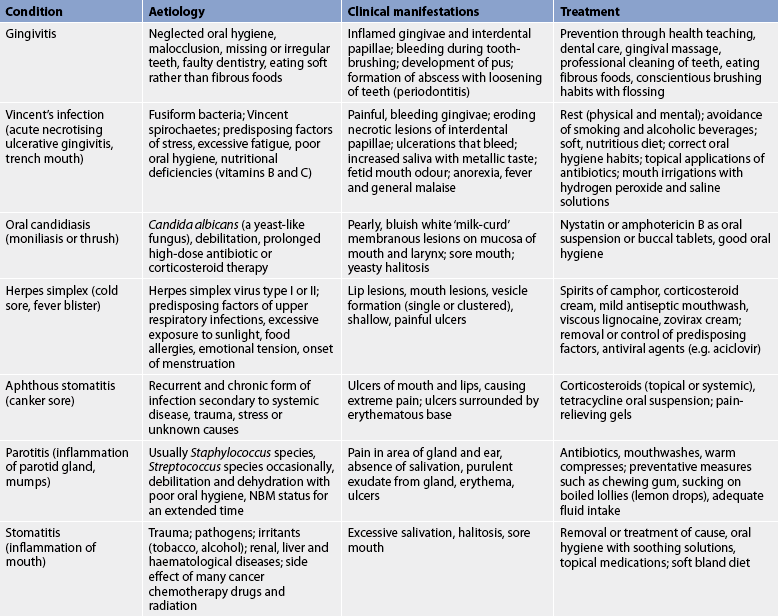

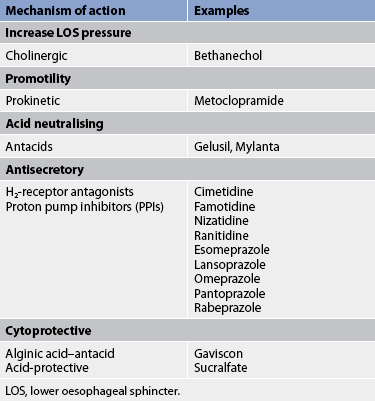

2. Describe the aetiology, clinical manifestations and treatment of common oral inflammations and infections.

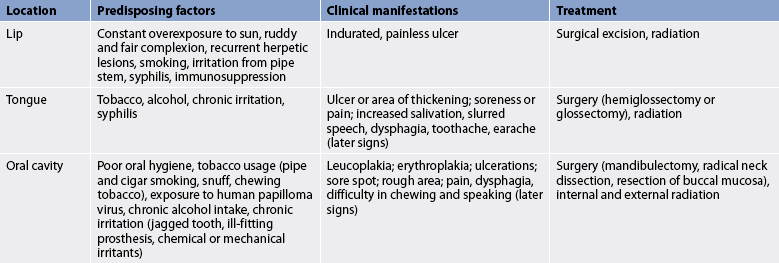

3. Describe the aetiology, clinical manifestations, complications, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of oral cancer.

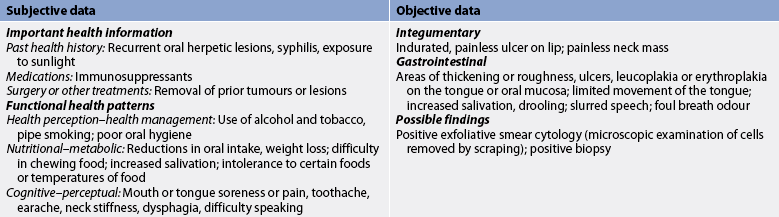

4. Explain the types, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, complications and multidisciplinary care, including surgical therapy and nursing management, of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and hiatus hernia.

5. Describe the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, complications and multidisciplinary care of oesophageal cancer, diverticula, achalasia and oesophageal strictures.

6. Differentiate between acute and chronic gastritis, including the aetiology, pathophysiology, multidisciplinary care and nursing management.

7. Explain the common aetiology, clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

8. Compare and contrast gastric and duodenal ulcers, including the aetiology and pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, complications, multidisciplinary care and nursing management.

9. Describe the clinical manifestations, multidisciplinary care and nursing management of gastric cancer.

10. Identify the common types of food poisoning and the nursing responsibilities related to food poisoning.

Nausea and vomiting

Nausea and vomiting are the most common manifestations of gastrointestinal (GI) diseases. Nausea is a feeling of discomfort in the epigastrium with a conscious desire to vomit. Vomiting is the forceful ejection of partially digested food and secretions (emesis) from the upper GI tract. Vomiting is a complex act that requires the coordinated activities of several structures: closure of the glottis, deep inspiration with contraction of the diaphragm in the inspiratory position, closure of the pylorus, relaxation of the stomach and lower oesophageal sphincter, and contraction of the abdominal muscles with increasing intraabdominal pressure. These simultaneous activities force the stomach contents up through the oesophagus, into the pharynx and out of the mouth. Although nausea and vomiting can occur independently, they are usually closely related and treated as one problem.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Nausea and vomiting are found in a wide variety of GI disorders, as well as in conditions that are unrelated to GI disease. These include pregnancy, infectious diseases, central nervous system (CNS) disorders (e.g. meningitis, CNS tumour), cardiovascular problems (e.g. myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure), metabolic disorders (e.g. Addison’s disease, uraemia), as side effects of drugs (e.g. opioids, chemotherapy, digoxin) and psychological factors (e.g. stress, fear).

Generally, nausea occurs before vomiting and is characterised by contraction of the duodenum and slowing of gastric motility and emptying. A single episode of nausea accompanied by vomiting may not be significant. However, if vomiting occurs several times, it is important that the cause be identified.

A vomiting centre (emetic centre) in the brainstem coordinates the multiple components involved in vomiting. This centre receives input from various stimuli. Neural impulses reach the vomiting centre via afferent pathways through branches of the autonomic nervous system. Visceral receptors for these afferent fibres are located in the GI tract, kidneys, heart and uterus. When stimulated, these receptors relay information to the vomiting centre, which then initiates the vomiting reflex (see Fig 41-1).

Figure 41-1 Stimuli involved in the act of vomiting. CTZ, chemoreceptor trigger zone; GI, gastrointestinal.

In addition, the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) located in the brainstem responds to chemical stimuli of drugs and toxins. The CTZ also plays a role in vomiting when it is due to labyrinthine stimulation (e.g. motion sickness). Once stimulated, the CTZ transmits impulses directly to the vomiting centre.

Vomiting can also occur when the GI tract becomes overly irritated, excited or distended. It can be a protective mechanism to rid the body of spoiled or irritating foods and liquids. Immediately before the act of vomiting, the person becomes aware of the need to vomit. The autonomic nervous system is activated, resulting in both parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system stimulation. Sympathetic activation produces tachycardia, tachypnoea and diaphoresis. Parasympathetic stimulation causes relaxation of the lower oesophageal (cardiac) sphincter, an increase in gastric motility and a pronounced increase in salivation. These manifestations are experienced immediately before vomiting.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Nausea is a subjective complaint. Anorexia (lack of appetite) usually accompanies nausea and is brought on by unpleasant stimulation involving any of the five senses. When nausea and vomiting are prolonged, dehydration can occur rapidly. In addition to water, essential electrolytes (e.g. potassium, sodium, chloride, hydrogen) are also lost. As vomiting persists, there may be severe electrolyte imbalances, loss of extracellular fluid volume, decreased plasma volume and eventually circulatory failure. Metabolic alkalosis can result from loss of gastric hydrochloric acid (HCl). Metabolic acidosis can occur because of the loss of bicarbonate when contents from the small intestine are vomited. However, metabolic acidosis as a result of severe vomiting is less common than metabolic alkalosis. Weight loss resulting from fluid loss is evident in a short time when vomiting is severe.

The threat of pulmonary aspiration is a concern when vomiting occurs in patients who are elderly or unconscious or who have other conditions that impair the gag reflex. Patients who cannot adequately protect their airway should be put in a semi-Fowler or side-lying position to prevent aspiration.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

The goals of multidisciplinary care are to determine and treat the underlying cause of the nausea and vomiting and to provide symptomatic relief. Determining the cause is often difficult because nausea and vomiting are manifestations of many conditions of the GI tract and of disorders of other body systems.

A careful history should elicit important information regarding times when the vomiting occurs, precipitating factors and a description of the contents of the vomitus or emesis. Associated symptoms such as abdominal pain, fever, diarrhoea, vertigo or similar illness identified among family and friends can assist diagnosis. The time of day at which the vomiting occurs is often helpful in determining the cause; for example, early morning vomiting is a frequent occurrence in pregnancy. Women are more likely than men to suffer from nausea and vomiting associated with both surgical procedures and motion sickness.

In all patients, differentiation must be made between vomiting, regurgitation and projectile vomiting. Regurgitation is a process in which gastric contents flow back into the mouth. Retching or vomiting seldom precedes it. Projectile vomiting is a very forceful expulsion of stomach contents without nausea and is characteristic of CNS tumours.

The presence of faecal odour and bile after prolonged vomiting indicates intestinal obstruction below the level of the pylorus. The presence of bile in the vomitus may suggest obstruction below the ampulla of Vater or bile reflux gastritis. The presence of partially digested food several hours after a meal is indicative of gastric outlet obstruction or a delay in gastric emptying.

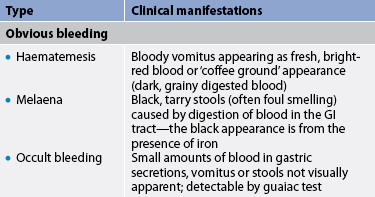

The colour of the vomitus aids in determining the presence and source of bleeding. Vomitus with a ‘coffee ground’ appearance is associated with bleeding in the stomach, where blood changes to dark brown as a result of its interaction with gastric acid. Bright-red blood indicates active bleeding, which is suggestive of a tear in the mucosal lining of the lower oesophagus or fundus of the stomach, bleeding gastric or duodenal ulcer or neoplasm, or bleeding oesophageal or gastric varices.

Drug therapy

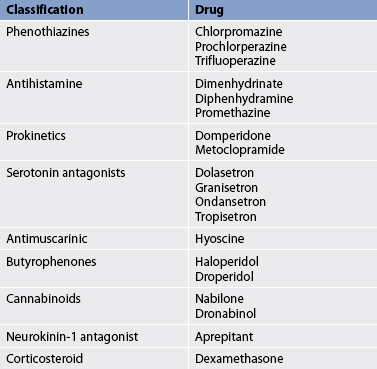

The use of drugs in the treatment of nausea and vomiting depends on the cause of the problem. Many different drugs can be used (see Table 41-1). Because the cause cannot always be readily determined, drugs must be used with caution. The use of antiemetics before the cause of the vomiting is established can mask the underlying disease process and delay diagnosis and treatment. Many of the antiemetic drugs act on the CNS at the level of the CTZ. In general, they block the neurochemicals that appear to trigger nausea and vomiting.

Drugs that control nausea and vomiting include antimuscarinics (e.g. hyoscine), antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine) and phenothiazines (e.g. chlorpromazine, prochlorperazine). Because many of these drugs have anticholinergic actions, they are contraindicated for patients with glaucoma, prostatic hyperplasia, pyloric or bladder neck obstruction, or biliary obstruction. They share many common side effects, which include dry mouth, hypotension, sedative effects, rashes and GI disturbances such as constipation. Consultation with a pharmacist may be indicated before administering these drugs to a patient with multiple medical problems who is taking other medications.

Other drugs with antiemetic properties include metoclopramide and domperidone. These drugs act both centrally and peripherally on dopamine receptors. Peripherally they enhance the release of acetylcholine, resulting in increased gastric emptying. Because of this effect, these drugs are considered prokinetics. (Prokinetics are types of drugs that enhance gastrointestinal motility by increasing the frequency and/or strength of contractions in the small intestine but without disrupting their rhythm.) However, about 10–20% of patients taking metoclopramide experience CNS side effects ranging from anxiety to hallucinations. Extrapyramidal side effects, including tremor and dyskinesias similar to those in Parkinson’s disease, may also occur. Although domperidone supposedly does not cross the blood–brain barrier and has fewer side effects when compared to metoclopramide, acute extrapyramidal (dystonic) reactions have been reported.

Antagonists to specific serotonin (5-HT) receptors have been found to act both centrally and peripherally to reduce nausea and vomiting. In particular, antagonists to the 5-HT3 receptors are effective in reducing cancer chemotherapy-induced vomiting, vomiting caused by total body radiation, GI motility disturbances, carcinoid syndrome, and nausea and vomiting related to migraine headache and anxiety. Serotonin antagonists, including ondansetron, tropisetron and dolasetron, act centrally in the vomiting centre, as well as within the GI tract, preventing local initiation of the vomiting reflex. Dexamethasone is used in the management of cancer chemotherapy-induced vomiting, usually in combination with other antiemetics. Dexamethasone alone or in combination with ondansetron reduces both acute and delayed chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Cannabinoids have been used to prevent chemotherapy-induced vomiting when other therapies are ineffective. They are also used to relieve nausea and vomiting in the palliative care of patients with the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Nutritional therapy

The patient with severe vomiting requires intravenous (IV) fluid therapy with electrolyte and glucose replacement until able to tolerate oral intake. In some cases a nasogastric (NG) tube and suction are used to decompress the stomach. Once the symptoms have subsided, oral nourishment, beginning with clear liquids, is started. Extremely hot or cold liquids are not usually well tolerated. Carbonated beverages at room temperature with the carbonation reduced and warm tea are more easily tolerated. The addition of dry toast or crackers may alleviate the feeling of nausea and help prevent vomiting. Water is the initial fluid of choice for rehydration by mouth. Sipping small amounts of fluid (5–15 mL) every 15–20 minutes is usually better tolerated than drinking large amounts less frequently.

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Source: Ulbricht CE, Basch EM. Natural standard herb and supplement reference: evidence-based clinical reviews. St Louis: Mosby; 2005. Natural Standard. Herbs and supplements. Available at www:naturalstandard.com, accessed 10 November 2010.

As the patient’s condition improves, a diet high in carbohydrates and low in fatty foods should be provided. Items such as a baked potato, plain jelly, cereal with milk and sugar, and boiled lollies may be added. Some patients find ginger and peppermint oil effective. Coffee, spicy foods, highly acidic foods and those with strong odours are often poorly tolerated. Food should be eaten slowly and in small amounts to prevent overdistension of the stomach. When solid foods have been reintroduced, fluids should be taken between meals rather than with meals. It is advised that the patient remain quietly relaxed for approximately 1 hour after meals. For breastfed babies, breast milk is usually best continued, but bottle-fed babies should be given clear liquids.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: NAUSEA AND VOMITING

NURSING MANAGEMENT: NAUSEA AND VOMITING

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

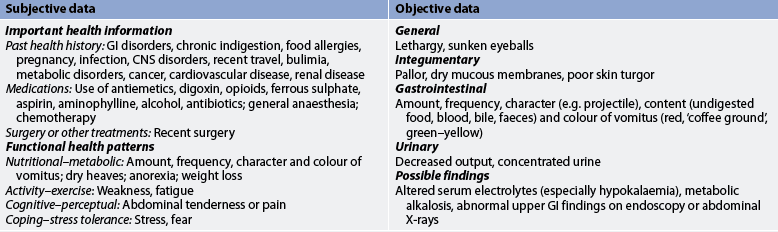

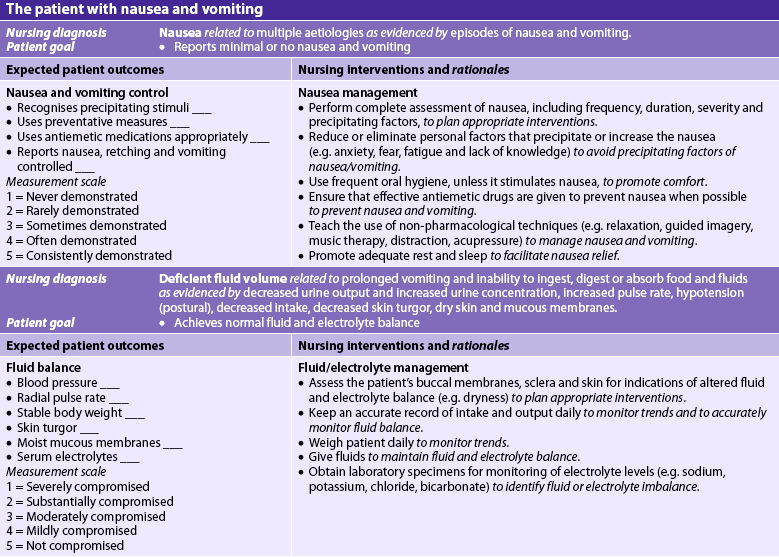

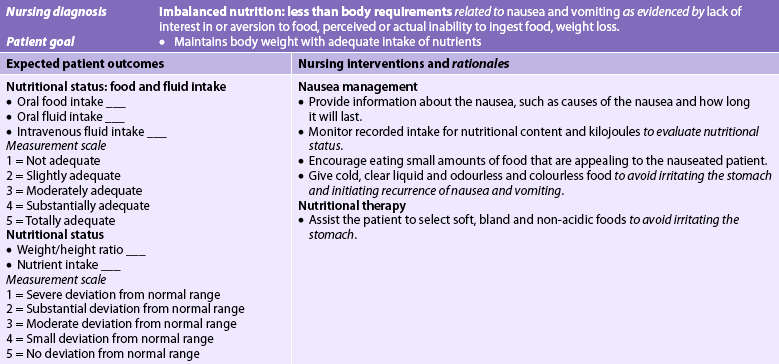

Each patient with a history of prolonged and persistent nausea or vomiting requires a thorough nursing assessment before a specific plan of care is developed. Although the conditions associated with nausea and vomiting are numerous, the nurse should have a basic understanding of the more common conditions and should be able to identify the patient who is at high risk. Knowledge of the physiological mechanisms involved in nausea and vomiting is important to the assessment process. Table 41-2 presents subjective and objective data that should be obtained from a patient with nausea and vomiting, regardless of the underlying cause.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with nausea and vomiting may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 41-1.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with nausea and vomiting will: (1) experience minimal or no nausea and vomiting; (2) have normal electrolyte levels and hydration status; and (3) return to a normal pattern of fluid balance and nutrient intake.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

The majority of individuals with nausea and vomiting can be managed at home. However, when nausea and vomiting persist regardless of home treatment strategies, hospitalisation may be necessary for diagnosis of the underlying problem. Until a diagnosis is confirmed, the patient is kept nil by mouth (NBM) and given IV fluids. An NG tube connected to suction may be necessary for the patient with persistent vomiting, as well as for the patient in whom the possible diagnosis may be bowel obstruction or paralytic ileus. Keeping the stomach empty reduces the stimulus to vomit. The NG tube should be secured to eliminate its movement in the nose and back of the throat because this can stimulate nausea and vomiting.

Paediatric considerations: nausea and vomiting

Babies and children can dehydrate quickly, especially if they also have diarrhoea. Children under 6 years of age should be examined if vomiting persists for more than 12 hours or if any physical signs of dehydration are present, such as rapid breathing and pulse rate, dry lips and oral mucosa, or sunken eyes and fontanelle.

Gerontological considerations: nausea and vomiting

The older patient experiencing nausea and vomiting requires careful assessment and monitoring, particularly during periods of fluid loss and subsequent rehydration therapy. Older patients are more likely to have cardiac or renal insufficiency that places them at greater risk of life-threatening fluid and electrolyte imbalances. In addition, excessive replacement of fluid and electrolytes may result in adverse consequences for the elderly person who has heart failure or renal disease. Finally, the older adult with a decreased level of consciousness may be at high risk of aspiration of vomitus. Close monitoring of the patient’s physical status and level of consciousness during episodes of vomiting must be a primary concern for the nurse.

In addition, the elderly are particularly susceptible to the CNS side effects of antiemetic drugs; these drugs may produce confusion. Dosages should be reduced and efficacy closely evaluated. Safety precautions also should be instituted for these patients.

With prolonged vomiting, there is a possibility of dehydration and acid–base and electrolyte imbalances. The nurse plans care that includes accurate recording of intake and output, monitoring vital signs, assessing for signs of dehydration, proper positioning to prevent possible aspiration in the susceptible patient, and observing for changes in the patient’s general physical comfort and psychological status. The nurse takes responsibility for providing physical and emotional support; maintaining a quiet, odour-free environment; and giving explanations regarding any diagnostic tests or procedures performed.

Patients who are hospitalised for other health problems may be prone to episodes of nausea and vomiting. These individuals include the postoperative patient who is recovering from the effects of a surgical procedure, anaesthesia and pain. Nausea and vomiting are common side effects in the cancer patient receiving chemotherapeutic drugs (nursing care of the cancer patient is found in Ch 15).

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

The patient and family may need instructions on: (1) how to deal successfully with the unpleasant sensations of nausea; (2) methods of preventing nausea and vomiting; and (3) strategies to maintain fluid and nutritional intake. The occurrence of nausea or vomiting may be minimised if measures are taken to keep the immediate environment quiet, free of noxious odours and well ventilated. The avoidance of sudden changes of position and unnecessary activity is also helpful. Use of relaxation techniques, frequent rest periods and diversionary tactics may help prevent nausea and vomiting or facilitate a more rapid recovery from their effects. Cleansing the face and hands with a cool washcloth and mouth care between episodes increase the person’s comfort level. When the symptoms occur, all foods and drugs should be stopped until the acute phase is past.

If a medication is suspected as the cause, the healthcare provider should be notified immediately so that either the dosage can be altered or a new drug can be prescribed. The patient should be reminded that stopping the drug without consulting the healthcare provider may eliminate the immediate cause of the nausea and vomiting but that omission of the prescribed drug may have detrimental effects on health or the disease state.

When food is identified as the precipitating cause of nausea and vomiting, the nurse should help the patient solve the problem and identify when it was eaten, prior history with that food and whether anyone else in the family is sick.

When the patient believes some foods and fluids can be tolerated, the nurse might suggest that it would be helpful to begin with clear liquids, tea or broth, dry crackers or toast, and then plain jelly. Bland foods, such as pasta, rice and cooked chicken, are generally well tolerated in small amounts. An antiemetic drug should be taken only if prescribed by the doctor or nurse practitioner. Taking over-the-counter drugs for the relief of symptoms may make the condition worse.

Oral inflammations and infections

Oral infections and inflammations may be specific mouth diseases or they may occur in the presence of some systemic diseases, such as leukaemia or vitamin deficiency. When oral inflammations and infections are present, they can severely impair the ingestion of food and fluids. Common inflammations and infections of the oral cavity are presented in Table 41-3.

Oral, oesophageal and gastric problems

HEALTH DISPARITIES

• The incidence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus in males in Australia has risen dramatically, with an average increase of 23.5% per year over the past 20 years. This increase is not seen in women.

• Gastric cancer is two to five times more common in Māori and Pacific Islander populations than it is in European New Zealanders.

• Māori descent is a consistent indicator of poorer survival from upper gastrointestinal cancer in New Zealand.

• Areca (betel) nut chewed in Australia and New Zealand by immigrants from India is associated with oral leucoplakia and submucous fibrosis: both are considered to be risk factors for oral cancer.

The patient who is immunosuppressed (e.g. a patient with AIDS or receiving chemotherapy) is most susceptible to oral infections. Patients receiving corticosteroid inhalant treatment for asthma are at risk of oral infections, especially candidiasis.

Oral infections may predispose to infections in other body organs. For example, the oral cavity can be considered a potential reservoir for respiratory pathogens. In addition, oral pathogens have been associated with heart disease.

An important element in reducing oral infection and inflammation is good oral and dental hygiene. Management of oral infection and inflammation is focused on identification of the cause, elimination of infection, provision of comfort measures and maintenance of nutritional intake.

Oral cancer

Oral (or oropharyngeal) cancer may occur on the lips or anywhere within the mouth (e.g. tongue, floor of the mouth, buccal mucosa, hard palate, soft palate, pharyngeal walls and tonsils). In 2006, oral cancer was diagnosed in 354 New Zealanders1 and 2427 Australians, and 466 Australians died from the disease.2 Oral cancer is more common after 45 years of age. It occurs in all ethnic groups but is more common in men (male-to-female ratio 2:1). Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common oral malignant tumour (more than 90%). Mortality rates have been decreasing since the early 1980s. The 5-year survival rate for oral cancer is 60%,3 although the survival rate for Indigenous Australians and Māori is lower than that of the general population.

Most oral malignant lesions occur on the lower lip in men. Other common sites are the lateral border and undersurface of the tongue, the labial commissure and the buccal mucosa. Carcinoma of the lip has the most favourable prognosis of any of the oral tumours. This is probably because lip lesions are more apparent to the patient than other oral lesions and so are usually diagnosed earlier.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although the definitive cause of oral cancer is unknown, there are a number of predisposing factors (see Table 41-4). Factors that influence the development of oral cancer include tobacco use (e.g. cigar, cigarette, pipe, chewing tobacco), chewing of betel nut (areca nut), excessive alcohol intake and chronic irritation, such as from a jagged tooth or poor dental care. Individuals who smoke have a 7–10 times higher risk of developing oral cancer compared with non-smokers. Constant overexposure to ultraviolet radiation from the sun is also a factor in the development of cancer of the lip. Irritation from the pipe stem resting on the lip is a factor in pipe smokers. Human papilloma virus (HPV) has also been postulated to have a role in the development of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.4

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The common manifestations of oral cancer are leucoplakia, erythroplakia, ulcerations, a sore that bleeds easily and does not heal and a rough area (felt with the tongue). Patients may also report non-specific symptoms, including chronic sore throat and voice changes. Leucoplakia, called ‘white patch’ or ‘smoker’s patch’, is often considered a precancerous lesion, although fewer than 15% of these lesions actually transform into malignant cells. It is a whitish patch on the mucosa of the mouth or tongue. The patch becomes keratinised (hard and leathery) and is sometimes described as hyperkeratosis. Leucoplakia is the result of chronic irritation, especially from smoking. Erythroplakia (also known as erythroplasia), which is seen as a red velvety patch on the mouth or tongue, is also considered a precancerous lesion. More than 50% of cases of erythroplakia will progress to squamous cell carcinoma. Later symptoms of oral cancer are pain, dysphagia (difficulty swallowing) and difficulty in moving the jaw (e.g. chewing and speaking).

Cancer of the lip usually appears as an indurated, painless ulcer on the lip. The first sign of carcinoma of the tongue is an ulcer or area of thickening. Soreness or pain of the tongue may occur, especially when eating hot or highly seasoned foods. Cancerous lesions are most likely to develop in the proximal half of the tongue. Some patients experience limitation of movement of the tongue. Later symptoms of cancer of the tongue include increased salivation, slurred speech, dysphagia, toothache and earache. Approximately 30% of patients with oral cancer have an asymptomatic neck mass.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Biopsy of the suspected lesion with cytological examination is the most definitive diagnostic study for oral cancer. Oral exfoliative cytology involves scraping the suspicious lesion and spreading this scraping on a slide. Unlike biopsy, a negative cytological smear does not reliably rule out the possibility of a malignant condition but it may be used as an initial screening test. The toluidine blue test may also be used as a screening test for oral cancer. Toluidine blue is applied topically to stain an area and cancer cells preferentially take up the dye. However, the definitive diagnosis of cancer is based on biopsy and histology.5 Computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) are useful in the staging of oral cancer.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Multidisciplinary care of oral carcinoma usually consists of surgery, radiation, chemotherapy or a combination of these (see Box 41-1).

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

*Any of the following approaches may be used, depending on the primary lesion and the extent of metastasis.

Surgical therapy

Surgery remains the most effective treatment, especially for removing the central core of the tumour. Many of the operations are radical procedures involving extensive resections. Various surgical procedures may be performed, depending on the location and extent of the tumour. Some examples are partial mandibulectomy (removal of the mandible), hemiglossectomy (removal of half of the tongue), glossectomy (removal of the tongue), resections of the buccal mucosa and floor of the mouth, and radical neck dissection.

Because cancers of the oral cavity metastasise early to the cervical lymph nodes, a radical neck dissection is commonly performed. It includes wide excision of the involved primary lesion with removal of the regional lymph nodes, the deep cervical lymph nodes and their lymphatic channels. In addition, the following structures may be removed or transected (depending on the extent of the primary lesion): sternocleidomastoid muscle and other closely associated muscles, internal jugular vein, mandible, submaxillary gland, part of the thyroid and parathyroid glands, and spinal accessory nerve. A tracheostomy is commonly performed along with the radical neck dissection. Drainage tubes are inserted into the surgical area and connected to suction to remove fluid and blood.

Non-surgical therapy

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy are used together when the lesions are more advanced or involve several structures of the oral cavity. Chemotherapy may be used when surgery and radiation therapy fail or as initial therapy for smaller tumours. Chemotherapeutic agents used include 5-fluorouracil, methotrexate, cisplatin, carboplatin, paclitaxel, docetaxel and bleomycin. Combination drug therapies are also used. (Chemotherapy is discussed in Ch 15.) Brachytherapy with implantations of radioactive seeds has been used successfully to treat early-stage oral cancer.

Palliative treatment may be the best management when the prognosis is poor, the cancer is inoperable or the patient decides against surgery. Palliation aims to treat the symptoms and make the patient more comfortable. If it becomes difficult for the patient to swallow, a gastrostomy may be performed to allow for adequate nutritional intake (see Ch 39). Analgesic medication should be given freely to this patient. Frequent suctioning of the oral cavity becomes necessary when swallowing becomes difficult. (Other nursing measures for the terminally ill patient are discussed in Ch 9.)

Nutritional therapy

If patients have pre-existing depression, alcoholism or presurgery radiation treatment, they may be malnourished even before surgery. After radical neck surgery, the patient may be unable to take in nutrients through the normal route of ingestion because of swelling, the location of sutures or difficulty with swallowing. Parenteral fluids will be given for the first 24–48 hours. After this time, tube feedings are usually given via an NG or nasointestinal tube that was placed during surgery. Sometimes a temporary feeding gastrostomy may be the optimal choice and will be inserted prior to radiation treatment or surgery. (NG and gastrostomy feedings are described in Ch 39.) Cervical oesophagostomy and pharyngostomy have also been used. The nurse must observe for tolerance of the feedings and adjust the amount, time and formula if nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or distension occurs. The patient is instructed about the tube feedings. When the patient can swallow, small amounts of water are given. Close observation for choking is essential. Suctioning may be necessary to prevent aspiration.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ORAL CANCER

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ORAL CANCER

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from a patient with oral cancer are presented in Table 41-5.

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with oral cancer may include, but are not limited to, the following:

• imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to oral pain, difficulty chewing and swallowing, surgical resection and radiation treatment

• chronic pain related to the tumour and surgical radiation

• anxiety related to the diagnosis of cancer, uncertain future, the potential for disfiguring surgery, the potential for recurrence and prognosis

• ineffective coping related to body image change

• ineffective health maintenance related to lack of knowledge of the disease process and therapeutic regimen and unavailability of a support system.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with carcinoma of the oral cavity will: (1) have a patent airway; (2) be able to communicate; (3) have adequate nutritional intake to promote wound healing; and (4) have relief of pain and discomfort.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

The nurse has a significant role in the early detection and treatment of oral cancer. The nurse needs to provide the patient with information about predisposing factors (e.g. constant overexposure to the sun, tobacco and other irritants). Smoking, long-term use of chewing tobacco, alcohol, and exposure and infection with HPV are the major risk factors for oral cancer. Patients who are smokers should be informed about smoking cessation programs that are available in the community. (Smoking cessation is discussed in Ch 10.) Oral cancers have an increased chance of recurrence if risk factors are not reduced. The nurse should also teach correct oral hygiene and dental care and encourage the patient to seek preventative dental care. Risk factors should be identified. Because early detection of oral cancer is important, the patient should be taught to examine the mouth and to recognise the danger signals of oral cancer. If any of these signals are present, the patient should be instructed to visit a healthcare provider. Danger signals include unexplained pain or soreness in the mouth, unusual bleeding from the oral cavity, dysphagia and swelling or a lump in the neck.

Any individual with an ulcerative lesion that does not heal within 2–3 weeks should be referred to a doctor and a biopsy of the lesion should probably be performed. The nurse should inspect the patient’s oral cavity to detect suspicious lesions.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Preoperative care for the patient who is to have a radical neck dissection involves consideration of the patient’s physical and psychosocial needs. Physical preparation is the same as for any major surgery, with special emphasis on oral hygiene. A thorough assessment of alcohol intake should be done and measures to assess and treat withdrawal if it is a problem should be implemented early. Explanations and emotional support should include postoperative measures relating to communication and feeding. The surgical procedure should be explained to the patient and the nurse should make sure that the patient understands the information. Radical neck dissection and the related nursing management are discussed in Chapter 26.

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) is not a disease but a syndrome. GORD is defined as any clinically significant symptomatic condition or histopathological alteration presumed to be secondary to reflux of the gastric contents into the lower oesophagus. GORD is the most common upper GI problem seen in adults. Approximately 10–20% of the Western world experience GORD symptoms. There are approximately 61,049 hospital admissions per year in Australia for GORD.6

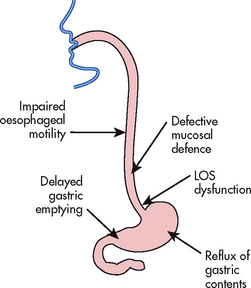

There is no single cause of GORD. Several factors or combinations of factors can be involved (see Fig 41-2). It results when the defences of the lower oesophagus are overwhelmed by the reflux of acidic stomach contents into the oesophagus. Predisposing conditions include hiatus hernia, incompetent lower oesophageal sphincter (LOS), decreased oesophageal clearance (ability to clear liquids or food from the oesophagus into the stomach) resulting from impaired oesophageal motility, and decreased gastric emptying. The acidic gastric secretions that reflux up into the lower oesophagus result in oesophageal irritation and inflammation (oesophagitis). In addition, the gastric enzyme pepsin and intestinal enzymes (e.g. trypsin) and bile salts are also corrosive to the oesophageal mucosa. The degree of inflammation depends on the amount and composition of gastric reflux and on the ability of the oesophagus to clear the acidic contents.

Figure 41-2 Factors involved in the pathogenesis of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD). LOS, lower oesophageal sphincter.

One of the primary factors in GORD is an incompetent LOS. An incompetent LOS results in a decrease in pressure in the distal portion of the oesophagus. As a result, gastric contents are able to move from an area of higher pressure (stomach) to an area of lower pressure (oesophagus) when the patient is in a supine position or has an increase in intraabdominal pressure. Decreased LOS pressure can be due to certain foods (e.g. caffeine, chocolate) and drugs (e.g. anticholinergics). Obesity is a risk factor for GORD, although the mechanism remains to be determined. Pregnant women are at greater risk of GORD. Cigarette and cigar smoking can also contribute to GORD. A common cause of GORD is a hiatus hernia, which is discussed on page 1086.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The symptoms of GORD vary from individual to individual. Heartburn (pyrosis) from gastro-oesophageal reflux is the most common clinical manifestation. It is caused by irritation of the oesophagus by the gastric secretions. Heartburn is described as a burning, tight sensation that is felt intermittently beneath the lower sternum and spreads upwards to the throat or jaw. Patients may also complain of dyspepsia. Dyspepsia is defined as pain or discomfort centred in the upper abdomen (mainly in or around the midline as opposed to the right or left hypochondrium). Episodes of hypersalivation (water brash) are another common complaint. Complaints of non-cardiac chest pain are more common in older adults with GORD.

Most individuals have mild symptoms, including heartburn that occurs about once a week after a meal, with no evidence of mucosal damage. However, the persistence of mild symptoms for a period of 5 years or more or symptoms associated with difficulty in swallowing should be evaluated. Heartburn that occurs more frequently than once a week, becomes more severe or occurs at night and wakes a person from sleep may be a sign of a more serious condition, and consultation with a healthcare provider is advised. Older adults who complain of a recent onset of heartburn should also receive medical evaluation.

Heartburn may occur following the ingestion of food or drugs that decrease the LOS pressure or are directly irritating to the oesophageal mucosa (see Box 41-2).

An individual with GORD may also report respiratory symptoms, including wheezing, coughing and dyspnoea. Nocturnal coughing can awaken the patient, resulting in disturbed sleep patterns. Otolaryngological symptoms include hoarseness, sore throat, a globus sensation (sense of a lump in the throat) and choking. Regurgitation (effortless return of food or gastric contents from the stomach into the oesophagus or mouth) is a fairly common manifestation of GORD. It is often described as hot, bitter or sour liquid coming into the throat or mouth. Gastric symptoms, including early satiety, post-meal bloating, nausea and vomiting, are related to delayed gastric emptying.

COMPLICATIONS

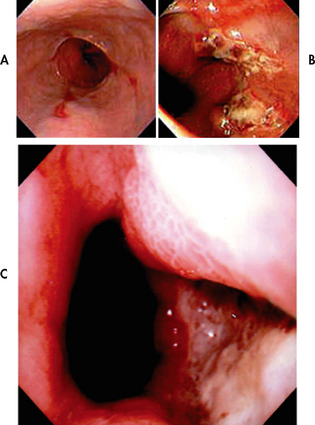

Complications of GORD are related to the direct local effects of gastric acid on the oesophageal mucosa. Oesophagitis (inflammation of the oesophagus) is a frequent complication of GORD. Oesophagitis with oesophageal ulcerations is shown in Figure 41-3. Repeated exposure may cause scar tissue formation and decreased distensibility of the oesophagus (oesophageal stricture). This may result in dysphagia.

Figure 41-3 Endoscopic images of the lower oesophagus in cases of reflux oesophagitis. A, Linear ulceration, B, Extensive circumferential ulceration. C, Deep ulceration.

Source: Grainger & Allison’s diagnostic radiology. 5th edn. Accessed on MD consult.

Another complication of GORD is Barrett’s oesophagus (oesophageal metaplasia). In Barrett’s oesophagus the normal squamous epithelium of the oesophagus is replaced with columnar epithelium. These cell changes are thought to be related to chronic reflux oesophagitis. However, patients with no history of reflux can still develop Barrett’s oesophagus. Approximately 5–15% of patients with chronic reflux have Barrett’s oesophagus.7 Barrett’s oesophagus is considered a precancerous lesion, which places the patient at risk of oesophageal cancer. Signs and symptoms of Barrett’s oesophagus can range from none to mild to bleeding and perforation. Because patients with Barrett’s oesophagus are at higher risk of adenocarcinoma, they need to be monitored on a regular basis (every 1–3 years) by endoscopy and biopsy.

Respiratory complications of GORD include cough, bronchospasm, laryngospasm and cricopharyngeal spasm. These complications are due to irritation of the upper airway by gastric secretions. With GORD there is also the potential for asthma, chronic bronchitis and pneumonia as a result of aspiration of the gastric contents into the respiratory system. Dental erosion, especially of the posterior teeth, may result from acid reflux into the mouth.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Diagnostic studies are performed to determine the cause of the GORD (see Box 41-3). A barium swallow is done to determine whether there is a hiatus hernia, which is a protrusion of the upper part of the stomach (called the gastric fundus) above the diaphragm. Endoscopy is useful in assessing the competence of the LOS and the extent of inflammation (if present), potential scarring and strictures. Biopsy specimens can be taken to diagnose peptic stricture, carcinoma of the oesophagus or Barrett’s oesophagus. Oesophageal manometric studies are performed to measure pressure in the oesophagus, as well as in the LOS. The determination of pH using specially designed probes in the laboratory or using ambulatory monitoring systems may demonstrate the presence of acid in the normally alkaline oesophagus. Radionuclide tests may also be performed to detect reflux of the gastric contents and the rate of oesophageal clearance.

BOX 41-3 GORD and hiatus hernia

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

*See Table 41-6.

Due to the cost and discomfort of diagnostic procedures, it has been suggested that high-dose proton pump inhibitor (PPI) treatment (explained in the section on drug therapy below) be used as a first step in the diagnosis of GORD.8 In patients with GORD, PPI treatment should result in a marked reduction or elimination of symptoms.7

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Most patients with GORD can be successfully managed by lifestyle modifications and drug therapy. These are long-term approaches requiring patient teaching and compliance with therapies. When these therapies are ineffective, surgery is an option.

Lifestyle modifications

The patient with GORD is taught to avoid factors that aggravate symptoms. Particular attention is given to diet and drugs that may affect the LOS, acid secretion or gastric emptying. Patients who smoke are encouraged to stop. Cigarette smoking has been associated with decreased acid clearance from the lower oesophagus.9

Nutritional therapy

Although diet does not cause GORD, food can aggravate symptoms. No specific diet is necessary, but foods that cause reflux should be avoided. Fatty foods stimulate the release of cholecystokinin, a hormone from the duodenum that decreases LOS pressure. High-fat foods also decrease the rate of gastric emptying. Foods that decrease LOS pressure, such as chocolate, peppermint, coffee and tea (see Box 41-2), should be avoided because they predispose to reflux. Milk products should be restricted and avoided at bedtime because milk increases gastric acid secretion. Small, frequent meals are advised to prevent overdistension of the stomach. The patient should avoid late evening meals and nocturnal snacking. Fluids should be taken between, rather than with, meals to reduce gastric distension. Certain foods (e.g. tomato-based products, orange juice) may irritate the acid-sensitive oesophagus and may need to be avoided. To reduce intraabdominal pressure, weight reduction is recommended if the patient is overweight.

Drug therapy

Drug therapy for GORD is focused on improving LOS function, increasing oesophageal clearance, decreasing the volume and acidity of reflux and protecting the oesophageal mucosa (see Table 41-6).

There are two approaches to drug therapy. The ‘step-up’ approach involves starting with antacids and over-the-counter histamine-2 receptor (H2R) antagonists and increasing to prescription H2R antagonists and finally PPIs. The ‘step-down’ approach involves starting with a PPI and over time titrating down to prescription H2R antagonists and finally over-the-counter H2R antagonists and antacids. A more recent approach is to use PPIs on-demand or as needed.

Antacids produce quick but short-lived relief of heartburn. They act by neutralising HCl. They should be taken 1–3 hours after meals and at bedtime. Over-the-counter antacids with or without alginic acid may be useful in patients with mild, intermittent heartburn. The alginic acid reacts with sodium bicarbonate and forms a viscous solution that floats to the surface of the gastric contents and coats the oesophagus, acting as a mechanical barrier to reflux. However, in patients with moderate-to-severe or frequent symptoms or in patients with documented oesophagitis, these regimens are not effective in relieving symptoms or healing erosive lesions.

Antisecretory agents decrease the secretion of HCl by the stomach. H2R antagonists (e.g. cimetidine, ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine) are available in over-the-counter (ranitidine) and prescription formulations. Over-the-counter preparations have lower drug dosages compared with prescription drugs. In prescription doses, H2R antagonists reduce symptoms and promote oesophageal healing in approximately 50% of patients. Patients frequently relapse (i.e. GORD symptoms return) when the drug is ceased.

PPIs such as omeprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole, rabeprazole and lansoprazole also decrease stomach HCl secretion. These agents act by inhibiting the proton pump mechanism that is responsible for the secretion of hydrogen ions. PPIs promote oesophageal healing in approximately 80–90% of patients but are more expensive than H2R antagonists. PPIs may also be beneficial in decreasing the incidence of oesophageal strictures, a complication of chronic GORD.

Another drug that may be used to treat GORD is sucralfate, an antiulcer drug used for its cytoprotective properties. Cholinergic drugs, such as bethanechol, may be used to increase LOS pressure, improve oesophageal emptying in the supine position and increase gastric emptying. However, the value of current cholinergic agents is limited because they also stimulate HCl secretion. Prokinetic (motility-enhancing) drugs, such as metoclopramide, promote gastric emptying and reduce the risk of gastric acid reflux (see Table 41-6).

Surgical therapy

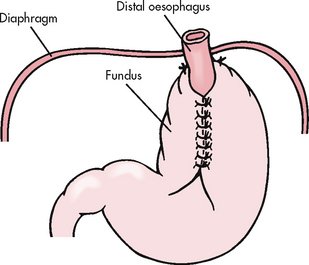

Surgical therapy (antireflux surgery) may be necessary if long-term conservative therapy fails, if a hiatus hernia is present or if complications such as oesophageal stricture and stenosis (narrowing), chronic oesophagitis and bleeding exist. Most surgical procedures are performed laparoscopically. The objective of surgical intervention for GORD is to reduce the reflux of gastric contents by enhancing the integrity of the LOS. In these procedures the fundus of the stomach is wrapped around the lower portion of the oesophagus to create a higher pressure barrier to reflux.

Laparoscopically-performed Nissen and Toupet fundoplications have become the standard surgical techniques used in antireflux surgery.10 The Nissen fundoplication is shown in Figure 41-4. The use of laparoscopic antireflux surgery for GORD has reduced complications, overall morbidity and the cost of hospitalisation compared with a thoracic or open abdominal approach.

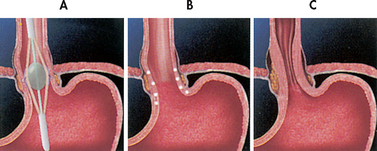

Endoscopic therapy

Endoscopic approaches to the management of GORD include endoscopic suturing devices for the lower oesophageal sphincter and endoscopic radiofrequency therapy.

The suturing devices insert sutures in the gastric cardia, to form small pleats that reduce the size of the opening of the oesophagus, thereby preventing oesophageal reflux Endoscopic radiofrequency therapy (Stretta procedure) uses a catheter that delivers radiofrequency energy to the smooth muscle of the gastro-oesophageal junction (see Fig 41-5).11 The radiofrequency energy causes tissue damage below the oesophageal lining forming scar tissue, which shrinks the surrounding tissue, resulting in a tightening of the lower oesophageal sphincter.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: GASTRO-OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: GASTRO-OESOPHAGEAL REFLUX DISEASE

Patients with GORD must avoid factors that cause reflux. A patient teaching guide is provided in Box 41-4.

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

The following are teaching guidelines for the patient and family:

1. Explain the rationale for a high-protein, low-fat diet.

2. Encourage the patient to eat small, frequent meals to prevent gastric distension.

3. Explain the rationale for avoiding alcohol, smoking (causes an almost immediate, marked decrease in LOS pressure) and beverages that contain caffeine.

4. Teach the patient not to lie down for 2–3 hours after eating, wear tight clothing around the waist or bend over (especially after eating).

5. Encourage the patient to sleep with the head of bed elevated on 10–15 cm blocks (gravity fosters oesophageal emptying).

6. Teach the patient about drugs, including the rationale for their use and common side effects.

7. Discuss strategies for weight reduction if appropriate.

8. Encourage the patient and family to share concerns about lifestyle changes and living with a chronic problem.

The patient who is a smoker should stop smoking. Smoking causes an almost immediate drop in LOS pressure and decreases the ability to clear acid from the oesophagus. The patient may need to be referred to other members of the healthcare team or to community resources for assistance in stopping smoking. (See Ch 10 for additional information related to smoking cessation.) Obesity is a contributing factor for GORD as intraabdominal pressure increases, thus overtaking the resting pressure of the LOS. The patient should be encouraged to participate in a weight reduction program. Substances that decrease LOS pressure and tone should be avoided (see Box 41-2). If stress seems to cause symptoms, measures to cope with stress should be discussed. The patient should also be taught about the possible side effects of drugs.

Nursing care for the patient who is having acute symptoms consists mainly of encouraging the patient to follow the necessary regimen. The nurse should ensure that the head of the bed is elevated to approximately 30° (usually on 10–15 cm blocks) and that the patient does not lie down during the first 2–3 hours after eating. Teaching the patient to avoid foods and activities that cause reflux is important (e.g. late-night eating should be avoided). The patient may be taking drugs to relieve heartburn, so the nurse must observe for side effects (see below) as well as evaluating the drugs’ effectiveness. Even when symptoms subside, the patient may need to continue drugs because the underlying problem is still present. Because of the link between GORD and metaplastic changes in the lower oesophagus (Barrett’s oesophagus), patients are instructed to see their healthcare provider if symptoms persist.

The nurse needs to instruct the patient about side effects of the drugs being taken. Side effects with H2R antagonists and PPIs are rare. Headache is the most common complaint of patients taking a PPI. Antacids have minimal side effects. Antacids that contain aluminium tend to cause constipation, whereas those that contain magnesium tend to cause diarrhoea. Several antacids are combinations of aluminium and magnesium and are designed to minimise these side effects. If the patient is taking bethanechol, side effects to observe for include urinary urgency, increased salivation, abdominal cramping with diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting and hypotension. Such side effects often limit the effectiveness of cholinergic agents in the treatment of GORD. Side effects of metoclopramide include restlessness, anxiety, insomnia and hallucinations. Side effects of sucralfate include drowsiness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, constipation, urticaria and rash.

Postoperative care focuses on concerns related to the prevention of respiratory complications, the maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance and the prevention of infection. If a thoracic approach is used, a chest tube is inserted. Assessment and management related to closed chest drainage are important (see Ch 27).

If an open abdominal incision is used, respiratory complications can occur because of the high abdominal incision. Respiratory assessment should include respiratory rate and rhythm, pulse rate and rhythm, and signs of pneumothorax (e.g. dyspnoea, chest pain, cyanosis). Deep breathing is essential to fully expand the lungs. Because most procedures are performed laparoscopically, the risk of respiratory complications is reduced. For some patients, the laparoscopic fundoplication is performed as an outpatient procedure. However, patients at risk of complications, including those with prior upper abdominal surgeries and those with comorbidities (e.g. cardiac disease, obesity), are hospitalised postprocedure.

The patient receives IV fluids and electrolytes until the return of peristalsis. Care should be taken to maintain patency of the NG tube (if present) to prevent the need to reinsert the tube. It is dangerous to attempt to replace the tube because of the possibility of perforation of the surgical repair. Immediately after the surgical procedure, the patient cannot voluntarily vomit or belch, and this may cause bloating and abdominal discomfort. When peristalsis returns, only fluids are given initially. Solids are added gradually so that the stomach is not overdistended. The nurse must maintain an accurate recording of intake and output and observe for fluid and electrolyte imbalances (see Ch 16).

After surgical therapy, there should be a decrease in symptoms of gastric reflux. However, the recurrence rate may range from 10% to 30% over a 20-year period following surgery. The patient should be instructed to report symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation. Such problems may be temporary and resolve with time. In the first month after surgery the patient may report mild dysphagia caused by oedema but it should resolve. The patient should advise the doctor of persistent dysphagia, epigastric fullness and bloating. A normal diet is gradually resumed. The patient should avoid foods that are gas forming and should try to prevent gastric distension. Food should be chewed thoroughly.

Following endoscopic therapy (e.g. Stretta procedure) the patient is monitored for complaints of chest pain. The patient is instructed to remain on clear liquids for 24 hours and then a soft diet for the next 2 weeks. Patients should take liquid medications to decrease irritation to the oesophageal mucosa. If nausea and vomiting occur, patients are instructed to contact their doctor. For 10 days following the procedure the patient should avoid non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

Hiatus hernia

Hiatus hernia is herniation of a portion of the stomach into the chest through an opening, or hiatus, in the diaphragm. It is also referred to as diaphragmatic hernia. The incidence of hiatus hernia is difficult to determine. However, it is the most common abnormality found on X-ray examination of the upper GI tract. Hiatus hernias are common in older adults and occur more often in women than in men.

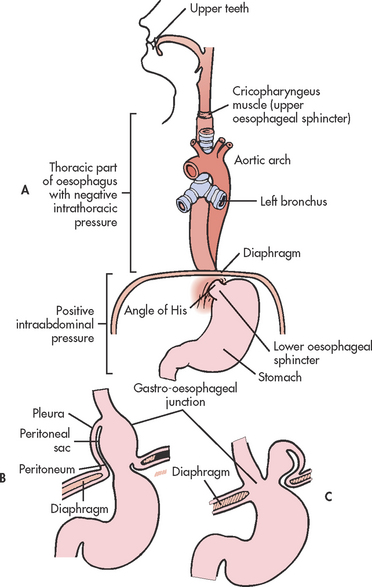

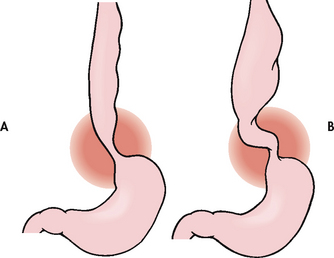

Hiatus hernias are classified into the following two types (see Fig 41-6):

1. Sliding: The junction of the stomach and oesophagus is above the hiatus of the diaphragm and a part of the stomach slides through the hiatus opening in the diaphragm. The stomach ‘slides’ into the thoracic cavity when the patient is supine and usually goes back into the abdominal cavity when the patient is standing upright. This is the most common type of hiatus hernia.

2. Paraoesophageal or rolling: The oesophagogastric junction remains in the normal position, but the fundus and the greater curvature of the stomach roll up through the diaphragm, forming a pocket alongside the oesophagus.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The actual cause of hiatus hernia is unknown. Many factors contribute to the development of a hiatus hernia. Structural changes, such as weakening of the muscles in the diaphragm around the oesophagogastric opening, are usually contributing factors. Factors that increase intraabdominal pressure, including obesity, pregnancy, ascites, tumours, tight underwear, intense physical exertion and heavy lifting on a continual basis, may also predispose to development of a hiatus hernia. Other predisposing factors are increased age, trauma, poor nutrition and a forced recumbent position, as when a prolonged illness confines the person to bed. In some cases, congenital weakness is a contributing factor.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Persons with a hiatus hernia are often asymptomatic. When present, the signs and symptoms of hiatus hernia are similar to those described for GORD. Heartburn, especially after a meal or after lying supine, is a common symptom. Patients may complain of dysphagia. Frequently the symptoms of hiatus hernia mimic gall bladder disease, peptic ulcer disease and angina. However, some patients with hiatus hernia have no symptoms. Reflux and discomfort are also associated with position, occurring soon or several hours after lying down. Bending over may cause a severe burning pain, which is usually relieved by sitting or standing. Other common precipitating factors of pain include large meals, alcohol and smoking. Nocturnal symptoms of heartburn are common, especially if the person has eaten before going to sleep.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications that may occur with hiatus hernia include GORD, oesophagitis, haemorrhage from erosion, stenosis (narrowing of the oesophagus), ulcerations of the herniated portion of the stomach, strangulation of the hernia and regurgitation with tracheal aspiration. Patients with a history of hiatus hernia are more at risk of hospitalisation for respiratory disease.12

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A barium swallow is an important diagnostic measure that may show the protrusion of gastric mucosa through the oesophageal hiatus in the patient with hiatus hernia. Endoscopic visualisation of the lower oesophagus provides information on the degree of mucosal inflammation or other abnormalities. Other tests are described in Box 41-3.

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: HIATUS HERNIA

NURSING AND COLLABORATIVE MANAGEMENT: HIATUS HERNIA

Conservative therapy

Conservative therapy

Conservative therapy of a hiatus hernia is similar to that described under GORD, including lifestyle modifications (e.g. reduction of intraabdominal pressure by eliminating constricting garments, avoiding lifting and straining, eliminating alcohol and smoking, elevating the head of the bed) and the use of antacids and antisecretory agents (PPIs, H2R antagonists). Elevation of the bed on 10–15 cm blocks assists gravity in maintaining the stomach in the abdominal cavity and also helps prevent reflux and tracheal aspiration. If overweight, the patient should be encouraged to lose weight.

Surgical therapy

Surgical therapy

Surgical management of a hiatus hernia involves reduction of the herniated stomach into the abdomen, closure of the defect, fixation of the stomach and an antireflux procedure. Several methods may be used: the Nissen fundoplication, the Toupet fundoplication or technique and the Belsey fundoplication. A fundoplication involves ‘wrapping’ the fundus of the stomach around the lower portion of the oesophagus in varying positions. This procedure reduces the hernia, provides an acceptable LOS pressure and prevents movement of the gastro-oesophageal junction. The Nissen fundoplication is shown in Figure 41-4. As in GORD, laparoscopically performed Nissen and Toupet techniques have become the standard surgical techniques for hiatus hernia.13 The Hill gastropexy is an abdominal surgical fundoplication approach that may be used in selected cases.

Gerontological considerations: GORD and hiatus hernia

The incidence of both GORD and hiatus hernia increases with age. It is associated with weakening of the diaphragm, obesity, kyphosis and the use of support briefs or other factors that increase intraabdominal pressure. Medications commonly taken by older patients, including nitrates, calcium channel blockers and antidepressants, will decrease LOS pressure. Others, such as NSAIDs and potassium, can irritate the oesophageal mucosa. Some older adults with hiatus hernia and GORD are asymptomatic. The first indications may include oesophageal bleeding secondary to oesophagitis or respiratory complications (e.g. aspiration pneumonia) related to aspiration of the gastric contents. The LOS may become less competent with ageing in some individuals.

The clinical course and management of GORD and hiatus hernia in the older adult are similar to those for the younger adult. With the increased use of laparoscopic procedures, surgical risks have been reduced. However, an older adult with cardiovascular and pulmonary problems may not be a good candidate for surgical intervention. In addition, changes in lifestyle, including the elimination of dietary factors, such as caffeine-containing beverages and chocolate, and elevating the head of the bed on blocks, may be more difficult for the older adult.

Oesophageal cancer

Oesophageal cancer (a malignant neoplasm of the oesophagus) is a disease that varies widely in its geographical distribution. There are parts of Asia in which the rate of oesophageal cancer is extremely high (it is the second most common type of cancer in China), whereas in Western societies the incidence is relatively low. However, that situation is changing and in Australia it is now listed as one of the top 10 causes of cancer deaths.2 In New Zealand, however, there has been a small decrease in the rate of deaths, from 232 deaths in 2002 to 208 in 2006.1 Because oesophageal cancer is rarely diagnosed in the early stages, the 5-year survival rate is currently only 17%.

The majority of oesophageal cancers are adenocarcinomas, with the remainder being squamous cell carcinomas. Adenocarcinomas arise from the glands lining the oesophagus and resemble cancers of the stomach and small intestine. The incidence of oesophageal cancer increases with age. One risk factor for oesophageal adenocarcinoma is Barrett’s oesophagus and it is estimated that 1 in 200 cases of Barrett’s oesophagus will progress to oesophageal cancer. (Barrett’s oesophagus is described under GORD on p 1082.)

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The cause of oesophageal cancer is unknown. Several important risk factors include Barrett’s metaplasia, smoking and excessive alcohol intake, obesity and dietary intake low in fruits and vegetables. Patients with injury to oesophageal mucosa such as ingestion of lye are also at greater risk. Occupational exposure to asbestos and cement dust has been linked to the gender differences in oesophageal cancer rates. Achalasia, a condition in which there is delayed emptying of the lower oesophagus, is associated with squamous cell cancer.

The majority of oesophageal tumours are located in the middle and lower portions of the oesophagus. The malignant tumour usually appears as an ulcerated lesion and has often advanced by the time the patient experiences symptoms. The tumour may penetrate the muscular layer and even extend outside the wall of the oesophagus. Obstruction of the oesophagus occurs in the later stages.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The onset of symptoms is usually late in relation to the extent of the tumour. Progressive dysphagia is the most common symptom and may be expressed as a feeling, felt substernally, as though food is not passing. Initially the dysphagia occurs only with meat, then with soft foods and eventually with liquids.

Pain develops late and is described as occurring in the substernal, epigastric or back areas and usually increases with swallowing. The pain may radiate to the neck, jaw, ears and shoulders. If the tumour is in the upper third of the oesophagus (cervical), symptoms such as sore throat, choking and hoarseness may occur. Odynophagia (pain on swallowing) may be present. Weight loss is fairly common. When oesophageal stenosis is severe, regurgitation of blood-flecked oesophageal contents is common.

COMPLICATIONS

Fatal haemorrhage may occur if the cancer erodes through the oesophagus and into the aorta. Oesophageal perforation with fistula formation into the lungs or trachea sometimes develops. The tumour may enlarge enough to cause oesophageal obstruction. There is spread via the lymph system, with the liver and lungs being common sites of metastasis.

Diagnostic studies

A barium swallow with fluoroscopy may demonstrate a narrowing of the oesophagus at the site of the tumour (see Box 41-5). Sometimes a crater is visible. Endoscopy with biopsy is necessary to make a definitive diagnosis of carcinoma by identification of malignant cells. In early tumours, chromoendoscopy with Lugol’s iodine or methylene blue may highlight abnormalities that are difficult to detect with standard endoscopy.14 Endoscopic ultrasonography is an important tool used to stage oesophageal cancer. A bronchoscopic examination may be performed to detect malignant involvement of the lung. CT scanning, PET scanning and MRI are also used to assess the extent of the disease.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

The treatment of oesophageal cancer depends on the location of the tumour and whether invasion or metastasis has occurred (see Box 41-5). Oesophageal cancer has a poor prognosis, mainly because it is not usually diagnosed until the disease is advanced. The best results may be obtained with a combination of surgery, endoscopic ablation, chemotherapy and radiation. Cancer in the cervical oesophagus is treated in a similar way to oral carcinoma, which was described earlier in this chapter.

Endoscopic approaches utilising photodynamic and/or thermal debulking techniques may be used to ablate mucosal adenocarcinoma or Barrett’s oesophagus with high-grade dysplasia. In photodynamic therapy a photosensitiser injected intravenously is absorbed to a greater degree by neoplastic tissue. Light is transmitted via a fibre that is passed through the endoscope and the photosensitiser is activated by the light, resulting in destruction of the cells. Thermal debulking techniques include argon plasma coagulation and laser therapy.15 Endoscopic mucosal resection is used to remove superficial or submucosal neoplasms.

The types of surgical procedures that can be performed are: (1) removal of part or all of the oesophagus (oesophagectomy) with use of a Dacron graft or segment of jejunum to replace the resected part; (2) resection of a portion of the oesophagus and anastomosis of the remaining portion to the stomach; and (3) resection of a portion of the oesophagus and anastomosis of a segment of colon to the remaining portion. The surgical approaches may be open (thoracic or abdominal incision) thoracoscopic or laparoscopic. Surgery may not be performed if the patient is older or in poor physical health. The use of minimally invasive oesophagectomy (e.g. laparoscopic vagal nerve sparing surgery) is being performed with increased frequency. It has the advantage of using a smaller incision, and decreasing intensive care unit and hospital stay, with fewer pulmonary complications. However, overall outcomes appear to be similar to open resection of the oesophagus.

Concurrent radiation and chemotherapy are used to slow the progression of oesophageal cancer. Currently, there is no standard single or combination drug therapy recommended for oesophageal cancer. Chemotherapeutic agents, such as cisplatin, carboplatin, capecitibine and fluorouracil, in combination with radiation before and/or after surgery are used. If the tumour is in the cervical section (upper third) of the oesophagus, radiation is usually indicated. A tumour in the lower third of the oesophagus is usually resected surgically. Chemotherapy is used in advanced oesophageal cancer to reduce symptoms, especially dysphagia, and to increase survival.

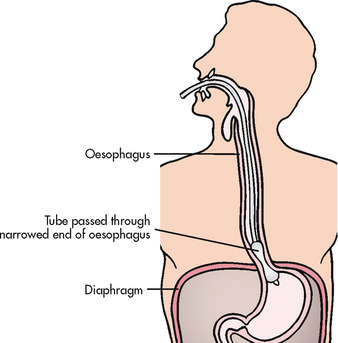

Palliative therapy consists of restoration of the swallowing function and maintenance of nutrition and hydration. Dilatation or stent placement, or both, can relieve obstruction. Dilatation is done with various types of dilators (e.g. Savary Gilliard); it often relieves dysphagia and allows for improved nutrition. Placement of a stent or prosthesis may help when dilation is no longer effective. Self-expandable metal stents are available with features to prevent stent migration and tumour ingrowth. The prosthesis is placed in the oesophagus and bridges the stenotic segment. Once expanded, food and fluids can pass through.

Endoscopic laser therapy or vaporisation of the tumour may be used in combination with dilatation. Obstruction recurs as the tumour grows but laser therapy can be repeated. Sometimes these procedures are combined with radiation therapy. Other measures for palliation include gastrostomy or oesophagostomy tube placements for nutrition support and pain management.

Nutritional therapy

After oesophageal surgery, parenteral fluids are given. When fluids are allowed after bowel sounds have returned, 30–60 mL of water are given hourly, with gradual progression to small, frequent bland meals. The patient should be in an upright position to prevent regurgitation of the fluid and should be observed for signs of intolerance to the feeding or leakage of the feeding into the mediastinum. Symptoms that indicate leakage are pain, increased temperature and dyspnoea. Symptoms of food intolerance include vomiting and abdominal distension. A gastrostomy or jejunostomy may be performed for the purpose of feeding the patient. (Gastrostomy and tube feedings are discussed in Ch 39.)

NURSING MANAGEMENT: OESOPHAGEAL CANCER

NURSING MANAGEMENT: OESOPHAGEAL CANCER

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

The patient should be asked about any history of GORD, hiatus hernia, achalasia or Barrett’s oesophagus and about tobacco and alcohol use. The patient should be assessed for progressive dysphagia and odynophagia (burning, squeezing pain while swallowing) and questioned regarding the type of substances ingested that cause dysphagia, such as meat, soft foods and liquids. The patient should also be assessed for pain (substernal, epigastric or back areas), choking, heartburn, hoarseness, cough, anorexia, weight loss and regurgitation (sometimes bloody).

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses for the patient with oesophageal cancer include, but are not limited to, the following:

• imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements related to dysphagia, odynophagia, weakness, chemotherapy and radiation therapy

• chronic pain related to the tumour

• fluid volume deficit related to inadequate intake

• risk of aspiration related to impaired oesophageal function

• anxiety related to the diagnosis of cancer, uncertain future and poor prognosis

• anticipatory grieving related to the diagnosis of life-threatening malignancy

• ineffective health maintenance related to lack of knowledge of the disease process and therapeutic regimen, unavailability of a support system and chronic debilitating disease.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with oesophageal cancer will: (1) have relief of symptoms, including pain and dysphagia; (2) achieve optimal nutritional intake; (3) understand the prognosis of the disease; and (4) experience a quality of life appropriate to disease progression.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

Patients with diagnosed Barrett’s oesophagus need to be counselled regarding regular follow-up evaluation. Health counselling should focus on cessation of smoking and excessive alcohol intake, as well as other risk factors for GORD. Maintenance of good oral hygiene and dietary habits (intake of fresh fruits and vegetables) may also be helpful.

Patients diagnosed with Barrett’s oesophagus need to be treated because this is considered a premalignant condition. Early diagnosis of oesophageal tumours is important but difficult because the onset of symptoms is usually late. Patients are encouraged to seek medical attention for any oesophageal problems, especially dysphagia. Intensive surveillance of patients with Barrett’s oesophagus has not been shown to reduce the mortality rate associated with oesophageal cancer. However, the American College of Gastroenterology surveillance guidelines recommend that patients showing evidence of high-grade dysplasia during screening should be evaluated for oesophageal resection.16

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

Preoperative care

Preoperative care

In addition to general preoperative teaching and preparation, particular attention to the patient’s nutritional needs and oral care is important. Many patients are poorly nourished because of the inability to ingest adequate amounts of food and fluids before surgery. A high-kilojoule, high-protein diet is recommended; it may have to be in liquid form. Some patients may need IV fluid replacement or total parenteral nutrition. The patient and/or family member should be instructed on how to keep an intake and output record and assess for signs of fluid and electrolyte imbalance. Some treatment protocols necessitate preoperative radiation and chemotherapy.

Meticulous oral care is essential. The mouth, including the tongue, gingivae and teeth or dentures, must be cleaned thoroughly. It may be necessary to use swabs or a gauze pad to scrub the mouth, including the tongue. Milk of magnesia with mineral oil may be used to remove crust formation. A mixture of mouthwash, ice and water makes a refreshing rinse.

Teaching should include information about chest tubes (if an open thoracic approach is used), IV lines, NG tube, gastrostomy feeding, pain management, turning, coughing and deep breathing. (General preoperative care is presented in Ch 17.)

Postoperative care

Postoperative care

The patient usually has an NG tube in place and there may be bloody drainage for 8–12 hours. The drainage gradually changes to greenish yellow. Assessment of the drainage, maintenance of the tube and oral and nasal care are nursing responsibilities. The NG tube should not be repositioned or reinserted without consulting the surgeon.

Because of the location of the incision and the general condition of the patient, emphasis is placed on the prevention of respiratory complications. Turning and deep breathing should be done every 2 hours. Use of an incentive spirometer helps to prevent respiratory complications.

The patient should be positioned in a semi-Fowler or Fowler position to prevent reflux and aspiration of gastric secretions. When the patient can drink fluids or eat, the upright position should be maintained for at least 2 hours after eating.

For patients who have had an oesophageal stent placed for palliation of symptoms, specific education about dietary modifications for management of nutritional intake is required. They need to avoid leafy vegetables, oranges, pineapples and unskinned fruits. Caution needs to be used with large medications, glucose sweets, bread and meat portions larger than minced beef size. The patient should be instructed to eat sitting up, chew for twice as long as usual and drink fizzy effervescent drinks frequently throughout their meal. Medication to suppress acid production is often required as oesophageal stents can allow reflux of stomach acid into the oesophagus.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

Many patients require long-term follow-up care after surgery for oesophageal cancer. The patient may undergo chemotherapy and radiation treatment following surgery. The patient needs encouragement and assistance in maintaining adequate nutrition. A permanent feeding gastrostomy may be required. The patient usually has fears and anxieties about a diagnosis of cancer. The nurse should know what the healthcare provider has told the patient about the prognosis and then provide appropriate counselling and support.

Referral to a home health nurse may be necessary for continued care of the patient (e.g. gastrostomy teaching, follow-up wound care). See Chapter 9 for management of the terminally ill patient and Chapter 15 for care of the cancer patient.

Other oesophageal disorders

OESOPHAGEAL DIVERTICULA

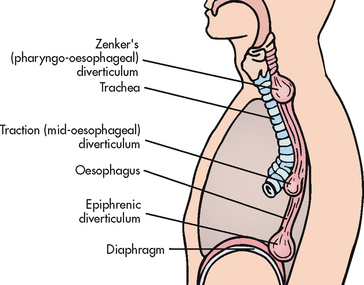

Oesophageal diverticula are sac-like outpouchings of one or more layers of the oesophagus. They occur in three main areas: (1) above the upper oesophageal sphincter (Zenker’s diverticulum), which is the most common location; (2) near the oesophageal midpoint (traction diverticulum); and (3) above the LOS (epiphrenic diverticulum) (see Fig 41-7).

Figure 41-7 Possible sites for the occurrence of oesophageal diverticula. These hollow outpouchings may occur just above the upper oesophageal sphincter (Zenker’s, the most common type of pulsion diverticulum), near the midpoint of the oesophagus (traction) and just above the lower oesophageal sphincter (epiphrenic).

Pharyngeal pouches (Zenker’s diverticula) occur most commonly in elderly patients (over 60 years) and typical symptoms include dysphagia, regurgitation, chronic cough, aspiration and weight loss (see Fig 41-8). Traction diverticulum may not cause signs and symptoms. The patient frequently complains of tasting sour food and smelling a foul odour caused by the stagnant food. Complications include malnutrition, aspiration and perforation. A diagnosis is easily established by barium studies.

Figure 41-8 Barium swallow of a patient with a Zenker’s diverticulum. Arrow points to the pharyngeal pouch.

There is no specific treatment for diverticula. Some patients find they can empty the pocket of food that collects by applying pressure at a point on the neck. The diet may have to be limited to foods that pass more readily (e.g. food that has been blended). Treatment of the diverticulum may be necessary if nutrition becomes disrupted. Treatment is surgical via an endoscopic or open approach. Open approaches have been associated with significant morbidity because the majority of patients are elderly and often have general medical problems. Treatment by endoscopic stapling diverticulotomy has become increasingly popular with its distinct advantages related to decreased complications.

OESOPHAGEAL STRICTURES