Chapter 59 NURSING MANAGEMENT: delirium, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease

1. Describe the aetiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies and collaborative management of delirium.

2. Define dementia and describe its impact on society.

3. Compare and contrast different aetiologies of dementia.

4. Explain the clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies and collaborative management of dementia.

5. Analyse the clinical manifestations, diagnostic studies and collaborative management of Alzheimer’s disease.

6. Evaluate the nursing management of the patient with Alzheimer’s disease.

7. Describe other neurodegenerative disorders associated with dementia, including Lewy body disease, Pick’s disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and normal-pressure hydrocephalus.

The three most common cognitive conditions in older adults are delirium (acute confusion), dementia and depression. Although this chapter focuses on delirium and dementia, depression is often associated with these conditions and they often occur simultaneously. It is important to be able to identify the distinguishing characteristics of each of these conditions, as the treatment is very different for each one. Many older patients who are admitted to hospital for acute treatment may experience delirium or already be suffering from degenerative disorders such as dementia. Nurses who work in an acute care setting should be able to recognise the symptoms of these conditions so that effective and evidence-based care can be given in a holistic and compassionate manner.

Delirium

Delirium, which is a state of temporary but acute reversible mental confusion or altered level of consciousness, is a common presenting feature of almost any medical or surgical disease in frail older adults. Approximately 10–40% of older people are delirious when admitted to hospital and up to 50% develop delirium during hospitalisation.1 Delirium is often unrecognised or misdiagnosed and results in higher morbidity and mortality.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The pathophysiological mechanism of delirium is poorly understood. Neuroimaging studies indicate that both cortical and subcortical structures (thalamus, basal ganglia and pontine reticular formation) are involved.2 The involvement of subcortical structures may explain the high risk of delirium in people with Parkinson’s disease. The neurotransmitter acetylcholine may also be a critical factor in the development of delirium. This is based in part on three observations: (1) anticholinergic drugs can precipitate delirium in older adults; (2) anticholinesterase agents (physostigmine) can reverse delirium caused by anticholinergic drug use; and (3) other risk factors for delirium, such as hypoglycaemia, hypoxia and thiamine deficiency, decrease the central nervous system (CNS) production of acetylcholine. Other neurotransmitters, including gamma-aminobutyric acid, noradrenaline, dopamine and serotonin, may also be involved in delirium but are less well studied.

Delirium associated with infection, inflammation and cancer may be related to the action of specific cytokines, such as interleukins and interferons.3 In addition, patients treated with cytokine therapies (e.g. interferon for hepatitis C) can develop neuropsychiatric side effects, including delirium.

Clinically, delirium is rarely caused by a single factor. It is often the result of the interaction of the patient’s underlying condition with a precipitating event. Delirium may present as a result of: advanced age; underlying cerebral disease such as dementia or substance abuse; chronic illnesses such as lung, heart or renal disease; infections; poor nutrition; drug interactions; metabolic or hormone disorders; and environmental factors such as sleep disruption, noise and pain that influence cerebral dysfunction.4 Delirium can also occur following a relatively minor insult in a vulnerable patient. For example, the patient with underlying health problems, such as congestive heart failure, cancer, cognitive impairment or sensory limitations, may develop delirium in response to a relatively minor change (e.g. use of a sleeping tablet). In other non-vulnerable patients, it may take a combination of factors (e.g. anaesthesia, major surgery, infection, prolonged sleep deprivation) to precipitate delirium.2 Delirium can also be a symptom of a serious medical illness, such as bacterial meningitis.

Understanding factors that can lead to delirium can help to determine effective interventions. Several factors identified as precipitating delirium are shown in Box 59-1. One of the most important risk factors for delirium is pre-existing dementia. Many of the conditions that can precipitate delirium are more common in older adults. In addition, older patients have limited compensatory mechanisms to deal with physiological insults such as hypoxia, hypoglycaemia and dehydration. Older adults are more susceptible to drug-induced delirium, in part because of their increased potential for using multiple drugs. Medications, including sedative–hypnotics, narcotics (in particular pethidine), benzodiazepines and drugs with anticholinergic properties, can cause or contribute to delirium, especially in older or vulnerable patients.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Patients with delirium can present with a variety of manifestations ranging from hypoactivity and lethargy to hyperactivity, including agitation and hallucinations.2,4 Patients can also have mixed delirium and manifest both hypoactive and hyperactive symptoms at different times of the day. Patients who are hypoactive may go undetected, as they do not appear to pose any challenges to their clinical management. Furthermore, their lack of demand on staff may be seen as their means of coping with the situation. In most patients, delirium usually develops over a 2–3 day period. The early manifestations often include inability to concentrate, irritability, insomnia, loss of appetite, restlessness and confusion. Later the manifestations may include agitation, misperception, misinterpretation and hallucinations. These symptoms can be challenging to manage in an acute medical/surgical situation. Symptoms will usually fluctuate between lucid and disruptive periods over the course of the day. The International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, suggests that for a definite diagnosis of delirium symptoms should be present in each of the following five areas of mental function: consciousness and attention, cognition, psychomotor, sleep–wake cycle and emotion.5

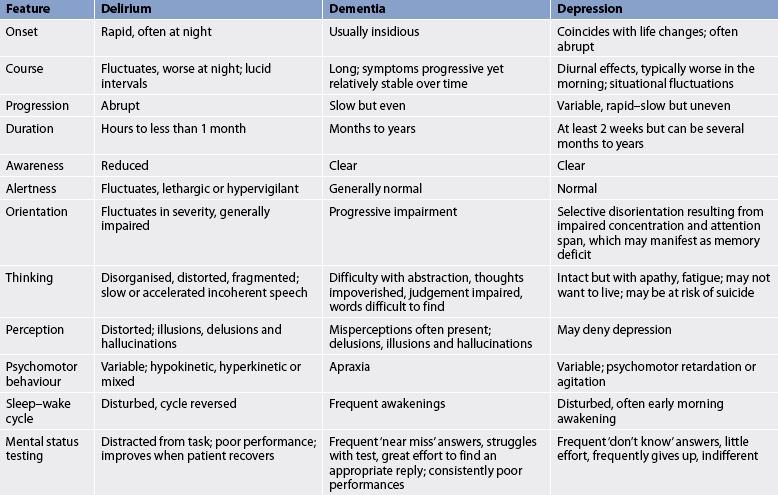

Manifestations of delirium are sometimes confused with dementia and depression, especially when the patient is an older adult. Table 59-1 compares the features of delirium, dementia and depression. Delirium should be suspected in any older person who shows a sudden change or fluctuation of mental state or behaviour.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

A careful history, including medical and mental status and physical examination, is the first step in the diagnosis of delirium. This includes careful attention to medications, both prescription and over-the-counter drug use. There are a large number of delirium assessment instruments. The following are the only ones that have been determined to be robust: the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM), the Delirium Rating Scale (DRS), the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale (MDAS) and the NEECHAM.6 A full assessment should include an interview with family members who are capable of describing the patient’s usual cognition state. Nursing notes should be reviewed for evidence of symptoms and commencement of symptoms.

Once delirium has been diagnosed, potential causes can be explored. These include careful review of the patient’s medical history, including medications. Laboratory tests include full blood count, serum electrolyte, urea and creatinine levels, electrocardiogram, urine analysis, liver function tests, and thyroid function and oxygen saturation level. Drug and alcohol levels may be obtained. If unexplained fever or nuchal rigidity (neck stiffness) is present, a lumbar puncture may be performed to exclude meningitis or encephalitis. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is examined for glucose, protein and the presence of bacteria. If the patient’s history includes head injury, appropriate X-ray or scans (i.e. brain-imaging studies, computed tomography [CT] or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI]) may be ordered.

COLLABORATIVE AND NURSING MANAGEMENT: DELIRIUM

COLLABORATIVE AND NURSING MANAGEMENT: DELIRIUM

Preventing delirium in patients at risk of delirium is important. Patient groups at risk include those with neurological disorders (e.g. stroke, dementia, CNS infection and Parkinson’s disease), sensory impairment and advanced age. Other risk factors include hospitalisation in an intensive care unit, lack of a watch or calendar and absence of reading glasses.4 Untreated pain may also precipitate delirium.

Care of the patient with delirium is focused on eliminating precipitating factors.4 If it is drug-induced, medications may be discontinued. As delirium can also accompany drug and alcohol withdrawal, drug screening may be performed. Fluid and electrolyte imbalances and nutritional deficiencies (e.g. thiamine) are corrected if appropriate. If the problem is related to environmental conditions (e.g. overstimulating or understimulating environment), changes should be made to the environment. If delirium is secondary to infection, appropriate antibiotic therapy is started. Similarly, if delirium is secondary to chronic illness, such as chronic renal failure or congestive heart failure, treatment is focused on these conditions.

Care of the patient experiencing delirium includes protecting them from harm. Priority is given to creating a calm and safe environment, including a reduction in noise and light levels where possible. This may include transferring the patient to a private room or one closer to the nurses’ station and planning for consistent staffing where possible. Reorientation and behavioural interventions should be used, such as encouraging family members to stay at the bedside and providing familiar objects such as family photographs, reassurance and reorienting information as to place, time and procedures.7 Clocks, calendars and listing the patient’s scheduled activities are also useful in reducing confusion.

Personal contact through touch and verbal communication can be important reorienting strategies. The patient’s sensory deficits should be corrected if they usually wear glasses or a hearing aid. The use of restraints should be avoided, while complementary therapies, such as relaxation techniques, aromatherapy therapy, music therapy and massage, may assist relaxation and reduce patient anxiety.8

Comprehensive, institutional-based programs focused on education, support, reorientation, anxiety reduction, screening and risk factor assessment, prevention of dehydration and sleep deprivation, and vision and hearing impairments may reduce overall episodes of delirium in hospitalised older patients.2 An interdisciplinary team approach is needed to reduce polypharmacy, decrease pain, enhance nutritional intake, reduce incontinence and prevent the adverse consequences of immobility, including skin breakdown.

Drug therapy

Drug therapy

Drug therapy is reserved for those patients with severe agitation, especially those whose agitation interferes with required medical therapy (e.g. fluid replacement, intubation and dialysis). Agitation can put the patient at risk of falls and injury. Drug therapy is used cautiously, because many of the drugs used to manage agitation have psychoactive properties.

Patients may be treated with low-dose antipsychotics (neuroleptics), such as haloperidol, to produce sedation.9 Care needs to be taken, as haloperidol may also produce early extrapyramidal reactions, such as dystonia (impairment of muscle tone), parkinsonism and akathisia. Older patients require smaller doses of antipsychotic agents because the ageing process limits their ability to metabolise and excrete medications. Older people on antipsychotic medications must be monitored carefully for the early and rapid onset of side effects. Early extrapyramidal side effects can lead to agitation, rigidity and difficulty in walking, leading to the risk of falls. Newer antipsychotics, including risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine, can be used to manage agitated behaviour in older adults. These drugs have fewer side effects than haloperidol.

Short-acting benzodiazepines (e.g. lorazepam) can be used to treat delirium associated with sedative and alcohol withdrawal or in conjunction with antipsychotics to reduce extrapyramidal side effects. However, antiparkinsonian agents, such as benzhexol and benztropine, are more commonly used for extrapyramidal disturbances. These drugs may worsen delirium caused by other factors and must be used cautiously.

Dementia

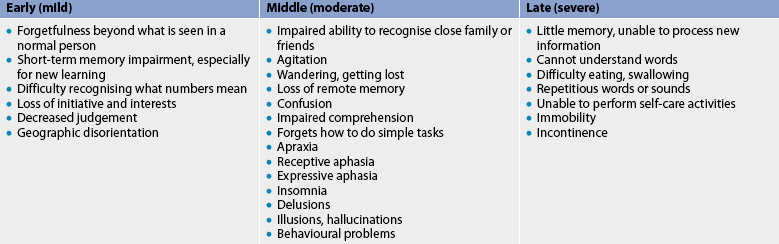

Dementia is a syndrome associated with a range of diseases characterised by the progressive impairment of brain functions, which include loss of memory, cognitive skills, orientation, attention, language, judgement and reasoning, and personality. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia. Ultimately, the decline in cognitive functioning results in alterations in the individual’s ability to work, social and family responsibilities, and activities of daily living. Clinical manifestations of dementia are classified as mild, moderate and severe (see Table 59-2).

Dementia is a disorder that occurs most often in older adults, with the prevalence increasing rapidly in persons over 70 years and in particular in those aged 85 years and over.10 The ageing of the population and the subsequent increase in the prevalence of dementia has resulted in dementia being viewed as an international public health concern. In New Zealand, there are approximately 40,746 people living with dementia (3% of whom are Māori), and this number is expected to rise to 74,821 by 2026.11 In Australia, approximately 256,529 people are living with dementia, and this number is expected to exceed 981,044 by 2050.9 Dementia is the key factor in triggering entry to residential aged care and has resulted in a high number of residents with dementia. Although it is difficult to put a figure on the number of people with dementia in residential aged care, the Australian Institute of Health & Welfare estimates that 32% of residents with high-care needs possibly have dementia and 59% probably have dementia.12 There are suggestions that a gap exists between supply and demand for both community and residential care for this population.10

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

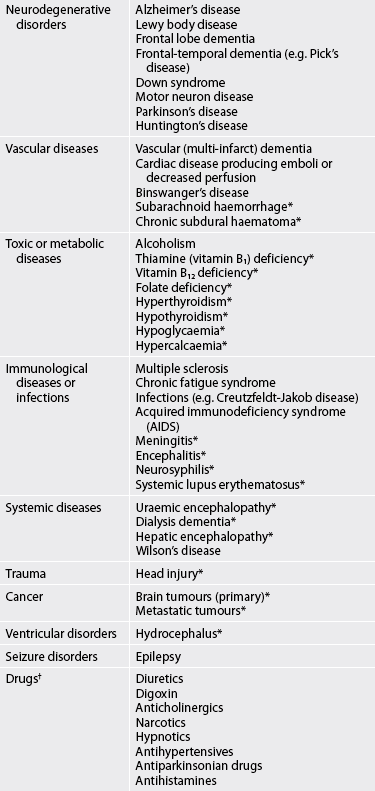

There are both treatable (potentially reversible) and non-treatable conditions that cause dementia (see Table 59-3). The two most common causes are neurodegenerative conditions (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease) and vascular disorders. Neurodegenerative conditions account for 60–80% of all dementias. Dementia is predominately a disorder of the very old (i.e. over 85 years) but it is not a normal part of ageing. A family history of dementia is a risk factor for dementia. Infectious conditions, such as bacterial meningitis and viral encephalitis, can result in both vascular and neurodegenerative changes that may ultimately result in dementia.

Vascular damage is the second most common cause of dementia. Vascular dementia, also called multi-infarct dementia, results from ischaemia, ischaemic–hypoxic or haemorrhagic brain lesions, which lead to extended damage to the brain and associated functions. Vascular dementia may be caused by a single stroke (infarct) or by multiple strokes of varying degrees of severity.

A history of smoking, cardiac arrhythmias (e.g. atrial fibrillation), hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease predispose to vascular dementia. Recently, elevated serum homocysteine and decreased folate and vitamin B12 serum levels have been associated with cognitive decline and dementia.13

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Depending on the cause of the dementia, the onset of symptoms may be insidious and gradual or somewhat more abrupt. Dementia associated with neurological degeneration is gradual and progressive over time. Vascular dementia presents as a history of stepwise deterioration. Early diagnosis and treatment may encourage a degree of recovery in the person with vascular dementia. However, it is not easy to distinguish the aetiology of dementia (vascular versus neurodegenerative) based on symptom progression alone. An acute (days to weeks) or subacute (weeks to months) pattern of change may be indicative of an infectious or metabolic cause, including encephalitis, meningitis, hypothyroidism or drug-related dementia.

Regardless of the cause of dementia, there are changes in cognitive functioning (see Table 59-2). Patients may complain of memory loss, mild disorientation and/or trouble with words and numbers. Often, it is a family member, in particular the spouse, who complains to the healthcare provider about the patient’s declining memory. Degeneration of the normal ageing brain accounts for the small changes in short-term memory that are common in older people but these do not affect activities of daily living. The memory loss accommodated in dementia is initially for recent events with past memories still intact. With progression of the disorder, memory loss develops to both recent and remote memory and ultimately affects the ability to perform self-care.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Early diagnosis is focused on determining the cause (e.g. reversible versus non-reversible factors). An important first step is a thorough medical, neurological and psychological history. A physical examination is performed to rule out contributing medical conditions. Screening for vitamin B12 deficiency and hypothyroidism are often performed. Based on patient history, testing for neurosyphilis (see Ch 60) may be performed. Cognitive evaluation and ongoing clinical monitoring of persons with mild cognitive impairment may assist with the identification of intervention and support if required, as well as diagnosis.

Mental status testing is an important component of patient evaluation. Patients with mild dementia may be able to compensate, making it difficult to evaluate cognitive function. Furthermore, people whose first language is not English may be disadvantaged because of language problems. Cognitive testing is focused on evaluating memory, ability to calculate, language, visual–spatial skills and alertness. Although there are other instruments, the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (see Box 59-2) or revised MMSE-2 is the most commonly used instrument to assess cognitive functioning.14

BOX 59-2 Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)

Registration

‘Listen carefully, I am going to say three words. You say them back after I stop. Ready? Here they are … HOUSE (pause), CAR (pause), LAKE (pause). Now repeat those words back to me.’ (Repeat up to five times, but score only the first trial.)

Reading

‘Please read this and do what it says.’ (Show examinee the words CLOSE YOUR EYES on the stimulus form.)

Source: Reproduced by special permission of the Publisher, Psychological Assessment Resource, Inc., 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, FL 33549, from the Mini Mental State Examination, by Marshal Folstein and Susan Folstein, Copyright 1975, 1998, 2001 by Mini-Mental, LLC, Inc. Published 2001 by Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc. Further reproduction is prohibited without permission from PAR, Inc. The MMSE and the revised version MMSE-2 can be purchased from PAR, Inc., by calling (1-813) 449 4065 or email: custsup@parinc.com

The cause of confusion is difficult to diagnose. A clinical history of the speed of onset of the confusion will help to differentiate between delirium and dementia. Manifestations of depression can mimic confusion and it is often mistaken for dementia in older adults. When dementia and depression do occur together (which may be in as many as 40% of dementia cases), the intellectual deterioration may be more extreme. Depression, alone or in combination with dementia, is treatable. The challenge is to make an early assessment.

Diagnosis of dementia related to vascular causes is based on the presence of cognitive loss, vascular brain lesions identified by neuroimaging techniques and the exclusion of other causes of dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease). Although both single photon emission CT (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET) scanning techniques can be used to characterise CNS changes in dementia, these tools are not routinely used in the initial diagnosis of dementia. There are no genetic markers or CSF markers that are currently recommended for routine evaluation of patients with dementia.

COLLABORATIVE AND NURSING MANAGEMENT: DEMENTIA

COLLABORATIVE AND NURSING MANAGEMENT: DEMENTIA

Collaborative and nursing management of the patient with dementia is similar to that described for Alzheimer’s disease (see below). Preventative measures for vascular dementia include treatment of risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, smoking, hyperfibrinogenaemia, hyperhomocysteinaemia, orthostatic hypotension and cardiac arrhythmias. (Stroke is discussed in Ch 57.) Cholinesterase inhibitors (discussed later in the chapter) that are used for patients with Alzheimer’s disease are also useful in patients with vascular dementia.

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a chronic, progressive, degenerative disease of the brain. It is the most common form of dementia, accounting for approximately 60–80% of all cases of dementia. AD is named after Alois Alzheimer, a German doctor who in 1906 described changes in the brain tissue of a 51-year-old woman who had died of an unusual mental illness.

About 70% of people who suffer from dementia have AD. The course of the disease can span 5–20 years and the majority of people need care during this time. The cost of care is high. In 2008 the total cost of dementia in New Zealand was estimated to be NZ$712.9 million, and in Australia the cost of care is projected to increase from A$11.1 billion in 2010 to A$59.6 billion in 2050. Government policy in both countries is, as far as possible, to provide support to older people remaining in their own home.10,11

The incidence of AD is approximately the same for all ethnic groups. However, recent research highlights that the prevalence of dementia is higher (at 12.4%) in the 45 years and older Indigenous Australian population living in rural and remote areas than the rate in the general Australian population (at 2.6%).15 The most common type of dementia found in the Indigenous population is Alzheimer’s, followed by vascular dementia. Because of the age profile of Indigenous communities, dementia is found in younger age groups, aged 45 years and older—life expectancy for Indigenous Australians is around 59 years for males and 65 years for females, compared with 76 years for all Australian males and 82 years for all Australian females (a difference of approximately 17 years for both males and females).16 The New Zealand European population has a life expectancy of 75 years for males and 80 years for females, while the Māori population has a life expectancy of 68 years for males and 72 years for females.17 Because the Māori live longer than Indigenous Australians, it is assumed they have an increased risk of AD.

There is increasing evidence that the risk factors for heart disease and stroke, such as hypertension and elevated cholesterol levels, may contribute to the risk of AD.18 Women are more likely than men to develop AD, primarily because they live longer. There appears to be a link between AD and Down syndrome, based on autopsy findings. People with Down syndrome may develop clinical signs around the age of 20, and by age 40 almost 100% of people with Down syndrome will have evidence of AD.

AETIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The exact aetiology of AD is unknown. Similar to other forms of dementia, age is the most important risk factor for developing the condition. However, AD is a disease that destroys brain cells, which is not a normal part of ageing. Only a small percentage of people younger than 60 years of age will develop AD. When AD develops in someone under the age of 60, it is referred to as early-onset AD. AD that becomes evident in individuals after the age of 60 is called late-onset AD (see the Health disparities box).

People in whom a clear pattern of inheritance within a family is established are said to have familial Alzheimer’s disease (FAD). Others in whom no familial connection can be made are termed sporadic. FAD is associated with earlier onset (before 60 years of age) and more rapid disease course. In both FAD and sporadic AD, the pathogenesis of disease is similar.

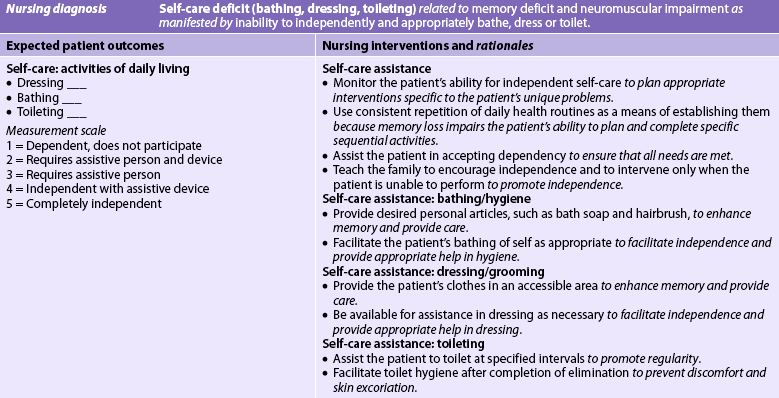

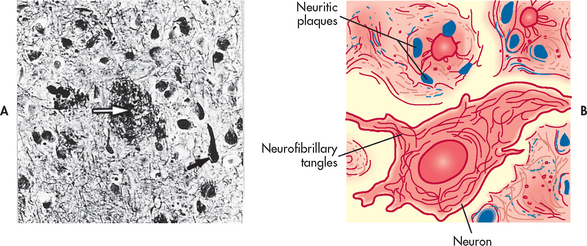

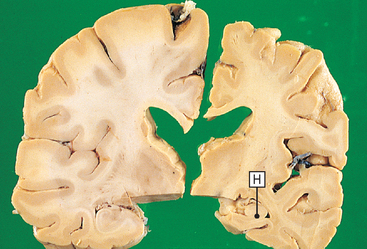

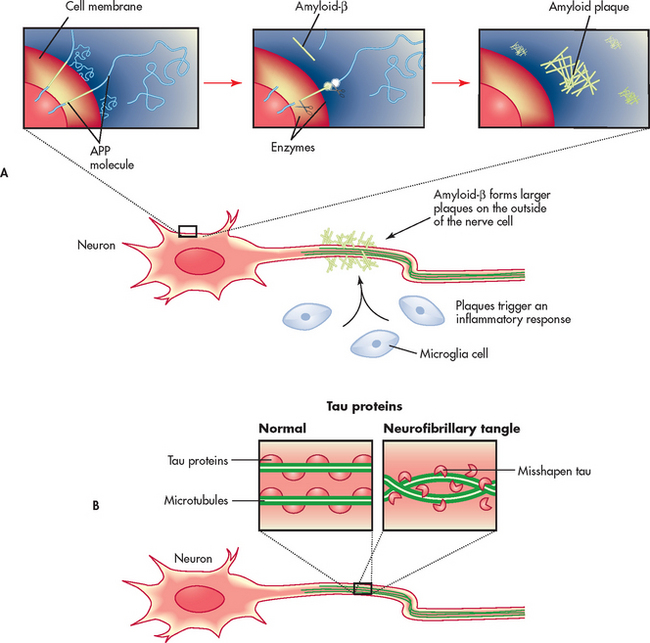

The characteristic findings in AD are the presence of abnormal clumps (neuritic or senile plaques) and tangled bundles of fibres (neurofibrillary tangles) in the brain (see Fig 59-1). The neuritic plaque is a cluster of degenerating axonal and dendritic nerve terminals that contain amyloid-β (A-β) protein. Neurofibrillary tangles are seen in the cytoplasm of abnormal neurons in those areas of the brain (hippocampus, cerebral cortex) most affected by AD (see Fig 59-2). In the cerebral cortex, they are found in those areas of the brain associated with cognition, learning, sleep and memory.

Figure 59-1 Pathological changes in Alzheimer’s disease. A, Senile plaque with central amyloid core (white arrow) next to a neurofibrillary tangle (black arrow) on the histological specimen from a brain autopsy. B, Schematic representation of neuritic plaque and neurofibrillary tangle.

Figure 59-2 Alzheimer’s disease. This photograph shows slices from two brains. On the left is a normal brain from a 70-year-old; on the right is the same region from a 70-year-old with Alzheimer’s disease. The diseased brain is atrophic with a loss of cortex and white matter, most marked in the hippocampal region (H).

HEALTH DISPARITIES

Genetic basis

Late onset (sporadic) (>60 years old at onset)

• Genetically more complex than early-onset form

• Presence of apolipoprotein E-4 (ApoE-4) gene on chromosome 19 increases the likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease

• If two ApoE-4 alleles are inherited, there is a higher risk of Alzheimer’s disease

• Presence of ApoE-2 allele is associated with a lower risk of Alzheimer’s disease

Clinical implications

• Alzheimer’s disease is the most common cause of dementia

• Overall the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease is three times higher among people with one affected parent than in those with no affected parents

• Genetic testing and counselling for family members of patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease may be appropriate

• If person tests positive for ApoE-4, it does not mean that the person will develop Alzheimer’s disease

Genetic factors may play a critical role in how the brain processes the A-β protein.18 Overproduction of A-β protein appears to be an important risk factor for AD. A-β protein is part of a larger protein called amyloid precursor protein (APP), which is involved in cell membrane function and is produced by cells throughout the body. Large amounts of APP are produced in the brain. Neuritic plaques are composed of A-β protein. Abnormally high levels of A-β protein are thought to produce cell damage either directly or through eliciting an inflammatory response and ultimately neuron death (see Fig 59-3, A).

Figure 59-3 Current aetiological theories for the development of Alzheimer’s disease. A, Abnormal amounts of amyloid-β are cleaved from the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and released into the circulation. The amyloid-β fragments come together in clumps to form plaques that attach to the neuron. Microglia react to the plaque and an inflammatory response results. B, Tau proteins provide structural support for the neuron microtubules. Chemical changes in the neuron produce structural changes in tau proteins. This results in twisting and tangling (neurofibrillary tangles).

Understanding why neurons produce A-β protein led researchers to examine the enzymes (and their genes) that are responsible for both the synthesis and processing of APP. Mutations in two genes have been shown to cause early-onset FAD: presenilin-1 (PSEN1) and presenilin-2 (PSEN2) (see the Health disparities box). When the presenilin-1 and presenilin-2 genes are mutated, they cause brain cells to overproduce A-β protein and this is associated with early-onset FAD.18

The first gene associated with both late-onset familial and sporadic AD was the epsilon-(E)-4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) gene on chromosome 19. ApoE may play a role in clearing amyloid plaques. ApoE comes in several different forms or alleles but three occur most commonly. People inherit one allele (ApoE-2, ApoE-3, ApoE-4) from each parent. Mutations in this gene result in greater amyloid deposition. The presence of ApoE-4 increases the risk of a person developing late-onset AD. However, the presence of the gene alone is not adequate to account for AD because many people with ApoE-4 do not develop AD.18

An important part of the neurofibrillary tangle is a protein called tau. Tau proteins in the CNS are involved in providing support for intracellular structure through their support of microtubules. Tau proteins hold the microtubules together like railway sleepers hold the railway tracks together. In AD, it appears that the tau protein is altered and, as a result, the microtubules twist together in a helical fashion (Fig 59-3, B). This ultimately forms the neurofibrillary tangles observed in the neurons of persons with AD.

The presence of neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles appears to be related to neuronal death. However, whether they are directly toxic or predispose to cell injury via other mechanisms remains to be determined. For example, examination of autopsied brain tissue from AD patients shows evidence of inflammatory changes. These findings suggest that AD may involve an inflammatory process. This inflammatory response may be elicited by cell damage or death secondary to A-β protein or neurofibrillary tangle formation.

Neuritic plaques and neurofibrillary tangles are not unique to patients with AD or dementia. They are also found in the brains of individuals without evidence of cognitive impairment. However, they are more plentiful in the brains of individuals with AD.

Cholinergic neurons are lost in people with AD, particularly in regions essential for memory and cognition. Other neurotransmitter systems, including serotonin and noradrenaline, also show losses over time in patients with AD. Such neurotransmitter changes are the basis of current drug therapies for AD.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Pathological changes often precede clinical manifestations of dementia by anywhere from 5 to 20 years. Mild cognitive impairment refers to a state of cognition and functional ability between normal ageing and early AD (see Table 59-4). More than 80% of patients with mild cognitive impairment develop AD within 10 years at a rate of 10–15% of patients per year. It is important to identify patients with mild cognitive impairment and initiate treatment strategies to stop or reverse the decline in cognitive function. If treated appropriately, the progression to onset of AD may be delayed.

TABLE 59-4 Comparison of normal forgetfulness and memory loss

| Normal forgetfulness | Mild cognitive impairment memory loss | Alzheimer’s disease memory loss |

|---|---|---|

| Sometimes misplaces keys, eyeglasses, or other items | Frequently misplaces items | Forgets what an item is used for or puts it in an inappropriate place |

| Momentarily forgets an acquaintance’s name | Frequently forgets people’s names and is slow to recall them | May not remember knowing a person |

| Occasionally has to search for a word | Has increasing difficulty finding desired words | Begins to lose language skills and may withdraw from social interaction |

| Occasionally forgets to run an errand | Begins to forget important events and appointments | Loses the sense of time; does not know what day it is |

| May forget an event from the distant past | May forget recent events or newly learned information | Has seriously impaired recent memory and difficulty learning and remembering new information |

| When driving, may momentarily forget where to turn, but quickly orients self | Becomes temporarily lost more often; may have trouble understanding and following a map | Becomes easily disoriented or lost in familiar places, sometimes for hours |

| Jokes about memory loss | Worries about memory loss; family and friends notice lapses | May have little or no awareness of cognitive problems |

Source: Adapted from rabins P. Memory. In: the Johns Hopkins white papers. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 2007.

A list of warning signs that include common manifestations of AD is shown in Box 59-3. The manifestations of AD can be categorised similarly to those for dementia as mild, moderate and severe (see Table 59-2). The rate of progression from mild to severe is highly variable from individual to individual and ranges from 3 to 20 years. Some patients may have mild cognitive impairment for years, whereas others, especially those with early-onset AD, may progress over a period of a few years from mild to severe impairment.

BOX 59-3 Early warning signs of Alzheimer’s disease

PATIENT & FAMILY TEACHING GUIDE

1. Memory loss that affects job skills. Frequent forgetfulness or unexplainable confusion at home or in the workplace may signal that something is wrong. This type of memory loss goes beyond forgetting an assignment, a colleague’s name, a deadline or a telephone number.

2. Difficulty performing familiar tasks. It is not abnormal for most people to become distracted and to forget something (e.g. leave something on the stove too long). People with Alzheimer’s disease may cook a meal but then forget not only to serve it but also that they made it.

3. Problems with language. Most people have trouble with finding the ‘right’ word from time to time. People with Alzheimer’s disease may forget simple words or substitute inappropriate words, making their speech difficult to understand.

4. Disorientation to time and place. While most individuals occasionally forget the day of the week or what they need from the store, people with Alzheimer’s disease can become lost on their own street, not knowing where they are, how they got there or how to get back home.

5. Poor or decreased judgement. Many individuals from time to time may choose not to dress appropriately for the weather (e.g. not wearing a coat or jumper on a cold evening). A person with Alzheimer’s may dress inappropriately in more noticeable ways, such as wearing a bathrobe to the shops or jumper on a hot day.

6. Problems with abstract thinking. For the person with Alzheimer’s disease this goes beyond challenges such as balancing a chequebook. The person may have difficulty recognising numbers or doing even basic calculations.

7. Misplacing things. For many individuals, temporarily misplacing keys, a purse or wallet is a normal, albeit frustrating, event. The person with Alzheimer’s disease may put items in inappropriate places (e.g. eating utensils in clothing drawers) but have no memory of how they got there.

8. Changes in mood or behaviour. Most individuals experience mood changes. People with Alzheimer’s disease tends to exhibit more rapid mood swings for no apparent reason.

9. Changes in personality. As most individual’s age, they may demonstrate some change in personality (e.g. become less tolerant). The person with Alzheimer’s disease can change dramatically, either suddenly or over time. For example, someone who is generally easygoing may become angry, suspicious or fearful.

10. Loss of initiative. People with Alzheimer’s disease may become and remain uninterested and uninvolved in many or all of their usual pursuits.

Source: Adapted from Alzheimer’s Association. Early warning signs. Chicago, IL: Alzheimer’s Association.

An initial sign of AD is a subtle deterioration in memory. Inevitably, this progresses to more profound memory loss that interferes with the patient’s ability to function. As the disease progresses, manifestations are more easily noticed and become serious enough to cause people with AD or their family members to seek medical help. Recent events and new information cannot be recalled. Personal hygiene deteriorates, as does the ability to concentrate and maintain attention. Ongoing loss of neurons in AD can cause a person to act in altered or unpredictable ways. Behavioural manifestations of AD (e.g. agitation) result from changes that take place within the brain. They are neither intentional nor controllable by the individual with the disease. Some patients develop psychotic manifestations (e.g. delusions, hallucinations).

With progression of AD, additional cognitive impairments are noted. These include dysphasia (difficulty comprehending language and oral communication), apraxia (inability to manipulate objects or perform purposeful acts), visual agnosia (inability to recognise objects by sight) and dysgraphia (difficulty communicating via writing). Eventually, long-term memories cannot be recalled and the ability to recognise family members and friends is lost. Non-cognitive problems that may occur include persistent wandering and sexually inappropriate behaviour.

Later in the disease, the ability to communicate and to perform activities of daily living is lost. In the late or final stages of AD, the person is unresponsive, incontinent and requires 24-hour care.

DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

The diagnosis of AD is primarily a diagnosis of exclusion. No single clinical test can be used to diagnose the disease. Where there is evidence of cognitive impairment, there is increased emphasis on early and careful evaluation of the patient. As indicated earlier in this chapter, there are many conditions that can cause manifestations of dementia, some of which are treatable or ‘reversible’ (see Table 59-3).

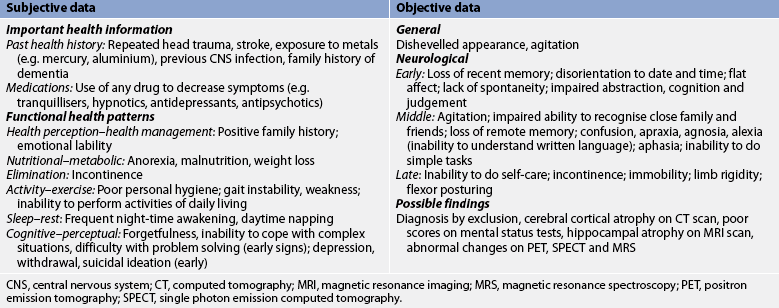

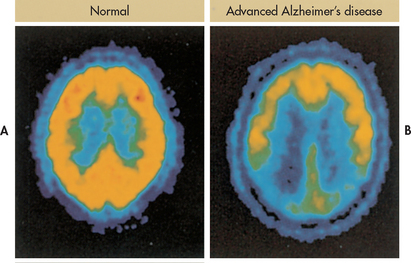

When all other possible conditions that can cause cognitive impairment have been ruled out, a clinical diagnosis of AD can be made. A comprehensive patient evaluation includes a complete health history, physical examination, neurological and mental status assessments, and laboratory tests (see Table 59-5). Brain imaging tests include CT or MRI. A CT or an MRI scan may show brain atrophy and enlarged ventricles in the later stages of the disease, although this finding occurs in other diseases and can be seen in persons without cognitive impairment. Newer techniques include SPECT, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) and PET (see Fig 59-4).

TABLE 59-5 Alzheimer’s disease

CNS, central nervous system; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; PET, positron emission tomography; SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography.

Figure 59-4 Positron emission tomography (PET) can be used to assist in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Radioactive fluorine is applied to glucose (fluorodeoxyglucose), which is taken up by metabolically active cells (yellow areas). A, A normal brain. B, Advanced Alzheimer’s disease is recognised by hypometabolism in many areas of the brain.

These techniques allow for detection of changes early in the disease as well as monitoring of treatment response. Blood levels of ApoE-4 protein may be obtained. However, blood levels are not conclusive for AD. While neuroimaging, neuropsychological testing and examination of genetic markers may provide a diagnosis of possible or probable AD, a definitive diagnosis requires examination of brain tissue and the presence of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques at autopsy.

Neuropsychological testing with tools such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (see Box 59-2) can help document the degree of cognitive impairment. Neuropsychological testing is important not only for diagnostic purposes but also to determine a baseline from which changes can be evaluated over time.

Research indicates that the brain in a person with AD contains extensive oxidative damage.18 A urine test that measures isoprostanes (by-products of fat metabolism associated with free radicals) may provide a mechanism for assessing risk of AD in those with mild cognitive impairment. However, widespread use of this marker is not currently available.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

There is currently no cure for AD. The collaborative management of AD is aimed at improving or controlling decline in cognition and controlling undesirable manifestations (see Box 59-4). Nurses have an important role in the provision of person-centred care and the coordination of the management team.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE

Diagnostic studies

History and physical examination, including psychological evaluation

Neuropsychological testing including Mini-Mental State Examination (see Box 59-2)

Brain imaging tests: CT, MRI, MRS, SPECT, PET

Serum glucose, creatinine, urea levels

Collaborative therapy

Drug therapy for cognitive problems (Table 59-6)

Drug therapy for behavioural problems (Table 59-6)

Assistance with functional independence

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; PET, positron emission tomography; SPECT, single photon emission computed tomography.

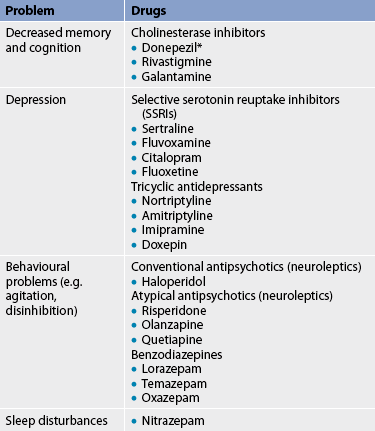

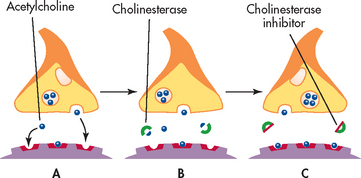

Drug therapy

Drug therapy for AD is listed in Table 59-6. Cholinesterase inhibitors are used in the treatment of mild and moderate dementia.19 They block cholinesterase, the enzyme responsible for the breakdown of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft (see Fig 59-5). Cholinesterase inhibitors include tacrine, donepezil, rivastigmine and galantamine. Unfortunately, they have resulted in various adverse drug effects. A more recent drug, memantine, inhibits N-Methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptors, prevents glutamate excitotoxicity and has minimal drug side effects.19 In people with moderate-to-severe dementia the best evidence-based therapy has been found to be the addition of memantine to donepezil therapy. Patients must meet specific criteria to be eligible for subsidised treatment with donepezil under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) in Australia, while in New Zealand donepezil has been subsidised since the end of 2010 and does not require special authority approval or specialist recommendation. Memantine and donepezil have been shown to either improve or stabilise cognitive decline in some people with AD. As a result, they can enhance functional abilities. However, these drugs do not cure or reverse the progression of the disease and it is not known whether their long-term administration will actually delay the progression of the neurological damage. Gastrointestinal side effects have been reduced through the production of the rivastigmine transdermal patch.20

TABLE 59-6 Alzheimer’s disease

* only available with special authority in Australia and MMSE scores need to show improvement to justify continued use; within New Zealand it is available on the PBS.

Figure 59-5 Mechanism of action of cholinesterase inhibitors. A, Acetylcholine is released from the nerve synapses and carries a message across the synapse. B, Cholinesterase breaks down acetylcholine. C, Cholinesterase inhibitors block cholinesterase, thus giving acetylcholine more time to transmit the message.

Drug therapy is often used for the management of behavioural problems that occur in people with AD. Conventional antipsychotic drugs (e.g. haloperidol) can be used to manage acute episodes of agitation, aggressive behaviour and psychosis. However, these antipsychotics, even in small doses, are associated with side effects in older adults, including early extrapyramidal symptoms, such as dystonia, parkinsonism and akathisia. Therefore, small doses of atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone, olanzapine and quetiapine are being used more commonly for behavioural management. They reduce aggression, improve behaviour and usually have fewer side effects.

Treating the depression that is often associated with AD may improve cognitive ability. Depression is often treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), including fluoxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine and citalopram. Anticonvulsant drugs, including carbamazepine, are also used to manage behavioural problems. These drugs tend to act as mood stabilisers.

There has been some debate about the ability of certain drugs, hormones and herbs (e.g. ginkgo biloba) to prevent or treat AD. Although there is one study that supports the hypothesis that low brain oestrogen may be a risk factor for developing AD, others do not support giving hormone replacement therapy to women with dementia.21 Herbal extracts such as ginkgo biloba (see the Complementary & alternative therapies box) have been tested in animal models; they appear to have multifunctional properties and their use in the treatment of AD looks promising.22 However, there is a need for caution, as there are conflicting findings where ginkgo biloba has been shown to provide no benefit.19 The lack of standardisation in study design may have influenced these findings and researchers have advocated for guidelines to evaluate complementary and alternative medicines.23

COMPLEMENTARY & ALTERNATIVE THERAPIES

Nursing implications

• May increase risk of bleeding. Use with caution in patients with bleeding disorders and those taking medications, herbs or supplements that increase risk of bleeding.

• May affect blood glucose. Caution is advised in patients with diabetes mellitus or those taking medications, herbs or supplements that affect blood glucose levels. Advise these patients to have close monitoring of blood glucose by a healthcare professional.

Source: DeKosky ST, Williamson JD, Fitzpatrick AL et al. Ginkgo biloba for prevention of dementia. JAMA 2008; 300:2253. Snitz BE, O’Meara ES, Carlson MC et al. Ginkgo biloba for preventing cognitive decline in older adults. JAMA 2009; 302:2663.

Long-term intake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) seems to decrease the risk of developing AD and delay the onset of the disease.24 However, more research is needed in this area. In addition, the increased potential for upper gastrointestinal bleeding when high doses of NSAIDs are used in older adults has encouraged caution in their use.

Antioxidants such as vitamin C, vitamin E and selegiline have been associated with a reduced risk of AD. They are thought to prevent nerve cell damage by destroying toxic free radicals. Free radicals are by-products of normal cell metabolism.

A number of ongoing clinical drug trials are attempting to find drugs that can limit or decrease the rate of disease progression, as well as manage the signs and symptoms of AD. These new agents will focus on enhancing communication between nerve cells, regulating defective cell processes (reducing A-β deposition), protecting nerve cells from damage and repairing nerve cells in the brain.

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

NURSING MANAGEMENT: ALZHEIMER’S DISEASE

Nursing assessment

Nursing assessment

Subjective and objective data that should be obtained from the patient with AD are presented in Table 59-5. Useful questions for the patient and family/carer are, ‘When did you first notice the memory loss?’ and ‘How has the memory loss progressed since then?’

Nursing diagnoses

Nursing diagnoses

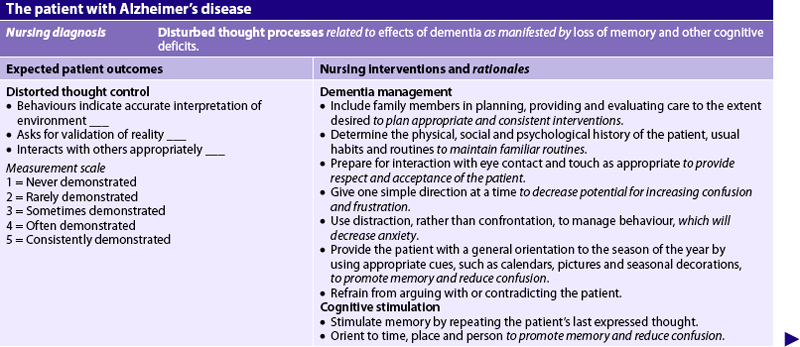

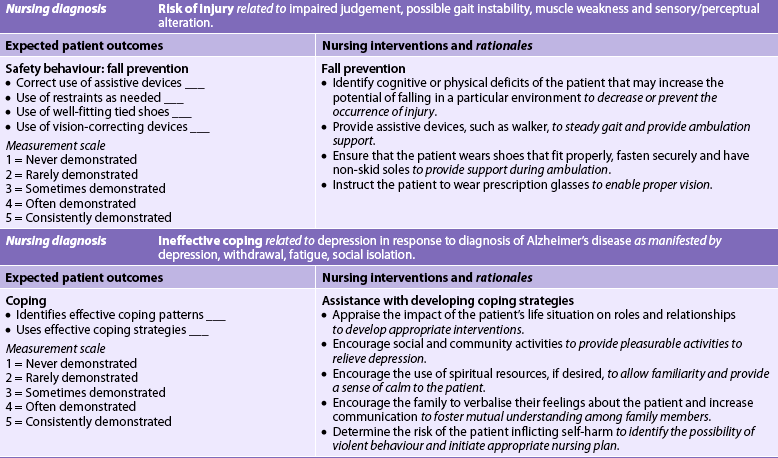

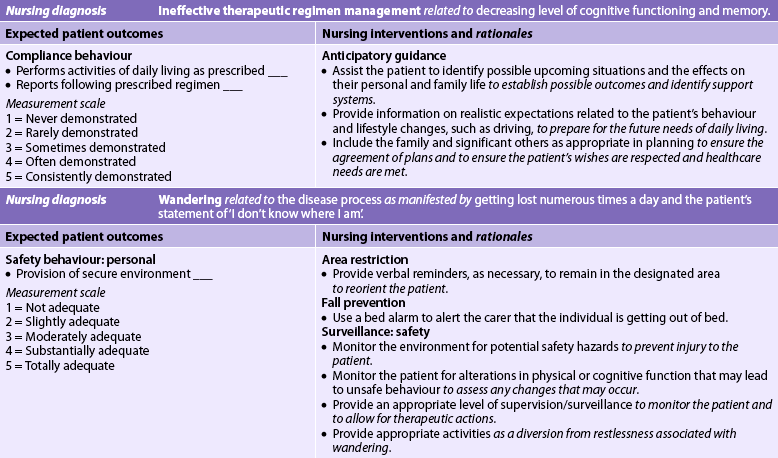

Nursing diagnoses for AD may include, but are not limited to, those presented in NCP 59-1.

Planning

Planning

The overall goals are that the patient with AD will: (1) maintain functional ability for as long as possible; (2) be maintained in a safe environment with a minimum of injuries; (3) have personal care needs met; and (4) have personhood and dignity maintained. The overall goals for the carer of a patient with AD are to: (1) reduce carer stress; (2) maintain personal health; and (3) cope with the long-term effects of caregiving.

Nursing implementation

Nursing implementation

Health promotion

Health promotion

There is no known method to reduce the risk of AD, although ongoing studies suggest that antioxidants may be beneficial. Because traumatic brain injury may be a risk factor for developing AD, the nurse should promote safety in physical activities and driving. Depression should be recognised and treated early. Genetic testing is not generally offered for AD.

Early recognition and treatment of AD are important. The nurse has a responsibility in terms of informing patients and their families about the early signs of AD and treatment. The warning signs of AD are shown in Box 59-3.

Acute intervention

Acute intervention

The diagnosis of AD is traumatic for both the patient and the family. Common responses following diagnosis include depression, denial, anxiety and fear, isolation and feelings of loss. The nurse is in an important position to assess for depression and suicidal ideation. Antidepressant drugs and counselling may be appropriate interventions to assist the patient. Furthermore, the nurse can assess the family’s ability to accept and cope with the diagnosis, as well as their support mechanisms and the safety of the home care environment.

As there is no current treatment for reversing AD, an important nursing responsibility is to ensure the person with dementia can maintain quality of life. The nurse can assist by working collaboratively with the patient’s carer to manage clinical manifestations effectively as they change over time and to teach the carer to manage the patient’s care.25

Patients with AD may be hospitalised for acute and chronic illnesses that may require surgical interventions. Their potential inability to communicate symptoms of health problems places the responsibility for assessment and diagnosis on carers and healthcare professionals. Hospitalisation of the person with AD can be a traumatic event for both the patient and the carer and can precipitate a worsening of the disease symptoms or result in delirium. Persons with AD hospitalised in the acute care setting need to be observed more closely because of the increased risk of delirium and concerns for safety; they also need to be frequently oriented to place and time, and given reassurance. The use of the same nurses caring for the patient may be helpful in reducing anxiety or disruptive behaviour. It is common to request a family carer to sit with their newly admitted family member, particularly during periods of agitation and/or wandering, as this may help to settle the person into new surroundings and reduce the need for sedation.26 The use of sedation increases the risk of falls and can lead to further disorientation and other complications, such as urinary and faecal incontinence.

Ambulatory and home care

Ambulatory and home care

While approximately half the people with AD live in the community, the insidious and progressive nature of the disease may necessitate placement in long-term care. Attention in these circumstances must continue to focus on the maintenance of the individual’s quality of life.

Patients with AD progress through stages of the disease at variable rates. Box 59-5 provides a family and carer teaching guide to assist them to care for the patient for as long as they wish to or are able.

FAMILY & CARER TEACHING GUIDE

Mild stage

1. Confirm the diagnosis. Many treatable (and potentially reversible) conditions can mimic Alzheimer’s disease (see Table 59-3).

2. Get the person to stop driving. Confusion and poor judgement can impair driving skills and potentially put others at risk.

3. Encourage activities such as visiting friends and family, listening to music, participating in hobbies and exercising.

4. Provide cues in the home, establish a routine and determine specific locations where essential items (e.g. glasses) need to be kept.

5. Do not correct misstatements or faulty memory.

6. Make plans for the future in terms of care options, financial concerns and personal preference for care.

Moderate stage

1. Install door locks for patient safety.

2. Provide protective wear for urinary and faecal incontinence.

3. Ensure that the home has good lighting, install handrails in stairways and bathroom, and remove rugs or ensure that they are tacked down.

4. Label drawers and taps (hot and cold) to ensure safety.

5. Develop strategies, such as distraction and diversion, to cope with behavioural problems. Identify and reduce potential triggers (e.g. reduce stress, extremes in temperature) for disruptive behaviour.

6. Provide memory triggers, such as pictures of family and friends.

Late stage

1. Provide a regular schedule for toileting to reduce incontinence.

2. Provide care to meet needs, including oral care and skin care.

3. Monitor diet and fluid intake to ensure their adequacy.

4. Continue communication through talking and touching.

5. Consider placement in a long-term care facility when providing total care becomes too difficult.

The nursing care needs of the patient change as the disease progresses, emphasising the need for individualised regular assessment, monitoring and support. Regardless of the setting, the severity of the problems and the amount of care required intensify over time. The specific manifestations of the disease will depend on the area of the brain involved. Nursing care is focused on decreasing clinical manifestations, preventing harm, and supporting the patient and carer through the disease process.

In the mild cognitive impairment phase, memory aids (e.g. calendars) may be beneficial. During this phase, depression is common. Depression is related to the diagnosis of an incurable disorder, as well as the impact of the disease on activities of daily living (e.g. driving, socialising with friends, participating in hobbies or recreational activities). Drug therapy with cholinesterase inhibitors appears to be most effective during the early stages. However, not all patients will show improvement. Drug therapy must be taken on a regular basis. Because memory is one of the key functions to be altered early in AD, drug compliance may require close monitoring.

After the initial diagnosis, patients need to be aware that the progression of the disease is variable. Effective management of the disease can slow the progress of the disease and decrease the burden on the patient, carer and family. However, decisions related to care should be made with the patient, family members and the healthcare team early in the disease. The nurse has a role in advising the patient and carer to initiate healthcare and advance directives/living wills and other important decisions while the patient still has the capacity to do so.

Adult community day care is one of the options available to people with AD. Although programs vary in size, structure, physical environment and degree of experience of staff, the common goals of all day-care programs for people with AD are to provide respite for the family and a protective and person-centred environment for the patient. The person with AD will benefit from stimulating activities that encourage their independence, and involvement in decision making and positive reinforcement can help their functional independence. Respite from the demands of care allows the carer to be more responsive to the patient’s needs.

Although adult day care may delay the transition to long-term care, as the disease progresses to gross impairment in cognitive function, memory and sense of self, the patient may need to be placed in a long-term care facility. Special dementia units that care for patients with AD are becoming increasingly common in long-term care settings. Such units are characterised by spaces that allow patients to walk freely yet are locked to prevent them from wandering outside of the grounds. The units encourage a person-centred environment for patients whereby the AD is not ignored but it no longer becomes the determinant of care practice. The focus is placed on the individual and meeting their needs.

As patients progress to the late stages (severe impairment) of the disease, they will have increased difficulty with the most basic functions, including walking and talking. Total care is required at this stage.

Specific challenges in caring for the person with AD across the phases of the disease are described below.

Behavioural problems

Behavioural problems

Behavioural disruptions occur in about 90% of patients with AD. Such problems can include repetitiveness (asking the same question repeatedly), delusions (false beliefs), hallucinations, agitation and aggression, altered sleeping patterns and wandering. These behaviours are often unpredictable and challenge carers. Nurses can assist in educating carers that these behaviours are not intentional and are often difficult to control. Behavioural symptoms often lead to placing the patient in institutional care.

The Needs-Driven Dementia-Compromised model suggests that disruptive behaviours are not symptoms of dementia but expressions of unmet needs.27 In patients with dementia, the hospital environment often leads to an increase in confusion, agitation and behavioural problems. Controlling the environment to reduce stimuli is the first step in behaviour management. This includes managing factors such as excessive noise and extremes in temperature, which can trigger behaviour disruptions. The use of consistent routines may help to manage behavioural symptoms. Using touch and eye contact when communicating with the patient can also orientate the patient and reduce anxiety.

Reminiscence therapy for people with dementia

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

Is reminiscence therapy (I) effective as a therapy (O) for older people with dementia (P)?

Best clinical practice

• Reminiscence therapy involves the discussion of past events, activities and experiences with another person or group of people.

• Prompts such as photographs, books and familiar items are used to assist discussion at least once a week.

• There is some evidence to suggest that reminiscence therapy is effective in improving mood in people with dementia.

Implications for nursing practice

• Nurses can use reminiscence therapy to help people with dementia to recall previous enjoyable life events.

• Reminiscence therapy can improve quality of life for the person with dementia and when carers assist the person with dementia to construct a life storybook this can help relatives to understand life events.

• Further research is required to understand the impact of reminiscence therapy on mood, cognition and wellbeing.

P, patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; O, outcome(s) of interest.

Other strategies to assist with behavioural disruption include redirection, distraction and reassurance. The person who is restless or agitated may be redirected to perform activities such as sweeping, raking or dusting. Strategies to distract the agitated person include sensory stimulation such as music therapy, watching DVDs, looking at family photographs, aromatherapy, sitting in a rocking chair, soothing massage or taking a walk. Reassurance involves letting the person know that they are safe and that they will be protected from danger, harm or embarrassment. An assessment of the situation is necessary to identify factors that may encourage disruptive behaviour. As verbal skills decline, the carer and nurse may need to rely on the patient’s body language to anticipate their care needs.

When non-pharmacological therapies are ineffective or there is concern about self-injury or for other patients’ welfare, disruptive behaviour may be treated with drug therapy (see Table 59-6). However, many of these drugs have adverse side effects that can be distressing for the patient and carer. Thus the side effects of the drugs need to be weighed against the distress and potential safety concerns for the patient created by the behaviour.

What are risk factors for falls in patients with dementia?

EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE

Clinical question

In patients with dementia or cognitive impairment (P), what factors (I) increase the risk of falls (O)?

Critical appraisal and synthesis of evidence

• Six prospective cohort studies (n = 825) with average patient age 65 years old.

• Patients with varying severity of cognitive impairments including Alzheimer’s disease were followed for 3 months to 3 years.

• Identified risk factors were motor and functional impairment, impaired vision, dementia type and severity, behavioural disturbances, fall history, antiseizure drugs and low bone density.

Implications for nursing practice

• All patients with cognitive impairment are at high risk for falls.

• Institute fall precautions on admission to healthcare agencies.

• Assess for fall risk factors and implement interventions specific to those factors (e.g. ensuring patient eyeglasses are worn for vision impairment).

P, Patient population of interest; I, intervention or area of interest; O, outcome(s) of interest.

Safety

Safety

The person with AD is at risk of danger to their personal safety. Such dangers include injury from falls, injury from ingesting dangerous substances, wandering, injury to others and self with sharp objects, fire or burns, and inability to respond to crises. These concerns increase the need for staff to be more vigilant and to position the patient where they can closely monitor them. As the patient may have difficulty navigating physical spaces and interpreting environmental cues, the environment must be adapted for them wherever possible. Stairwells must be well lit. Handrails are essential. Polished floor surfaces and linoleum can predispose to falls. In the bathroom, water temperature should be regulated, non-skid mats should be used in the bath or shower, and handrails should be installed in the bath and commode. In the home, throw rugs and extension cords should be removed to prevent falls. Ideally, the environment should be designed to support those with cognitive impairment.

People with AD often wander. They wander for different reasons, in different ways and with different outcomes. Some of the reasons for wandering are thought to be an expression of an unmet need, restlessness, curiosity or stimuli that trigger memories of earlier routines or a desire to leave the facility.28 Methods used to prevent wandering include restraints, drugs and locked doors. No evidence is currently available to support such methods as preventative barriers to wandering in people with AD.28

Pain management

Pain management

Pain in patients with AD is underdiagnosed and undertreated because of the difficulties these patients have in being able to articulate their needs. Specialist tools that help to recognise and document pain have been developed and validated.29 Untreated pain can result in alterations in the patient’s behaviour, such as increased vocalisation, agitation, withdrawal and changes in function. Pain should be treated appropriately with drug therapies and the patient’s response monitored.

Eating and swallowing difficulties

Eating and swallowing difficulties

Loss of interest in food and decreased ability to self-feed (feeding apraxia), as well as comorbidities, can result in significant nutritional deficiencies in patients with AD. Inadequate assistance with feeding may further add to the problem.

Pureed foods, thickened liquids and nutritional supplements can be used when chewing and swallowing become problematic in the later stages of the disease.30 Patients may need to be reminded to chew their food and to swallow. Distractions at mealtimes, including the television, should be avoided. A quiet and unhurried environment should be encouraged for eating with music and seating arrangements that are designed to increase communication between patients and nurses. Easy-grip eating utensils and finger foods may allow the patient to self-feed. Liquids should be offered frequently.

When oral feeding is not possible, alternative routes may be explored. Nasogastric (NG) feeding may be used for short periods, but for long-term use the NG tube is uncomfortable and may add further to the patient’s agitation. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube provides another option. Little long-term benefit has been noted in patients receiving PEG feedings, however, and as patients with AD are vulnerable to aspiration of feeding formula and tube dislodgement, the pros and cons of this treatment need to be considered carefully. (Nutritional support therapies are described in Ch 39.)

Oral care

Oral care

The oral health of people with dementia is significantly worse than for older people without dementia.31 Risk factors for dental decay in people with dementia include having existing dental caries, having many teeth and being older than 80 years.31 There is a potential for tooth decay due to decreased tooth brushing and flossing and pockets of food being held in the mouth due to swallowing difficulties. Dental caries and tooth abscess can add to patient discomfort and pain and subsequently may increase agitation. The patient’s mouth should be inspected regularly and mouth care provided if the patient is unable to perform self-care.

Infection prevention

Infection prevention

Urinary tract infections and pneumonia are the most common infections that occur in patients with AD,32 and such infections are ultimately the cause of death for many. Patients with AD are at increased risk of aspiration pneumonia. Immobility can also predispose to pneumonia. Reduced fluid intake, prostate hyperplasia in men, poor hygiene and urinary drainage devices (e.g. catheter) can predispose to bladder infection. Manifestations of infection—including changes in behaviour (e.g. restlessness), fever, cough (pneumonia) and pain on urination (bladder)—need to be evaluated and treated appropriately.

Skin care

Skin care

It is important to monitor the patient’s skin. Rashes, areas of redness and skin breakdown should be noted and treated as appropriate. In the late stages, incontinence along with immobility and undernutrition can place the patient at risk of skin breakdown. The skin should be kept dry and clean and the patient’s position changed regularly to avoid areas of pressure over bony prominences.

Elimination problems

Elimination problems

During the middle and late stages of AD, urinary and faecal incontinence become a problem. Scheduled toileting, such as first thing in the morning and before and after meals, in combination with prompting and praising may reduce elimination problems.26

If the patient experiences liquid stools without a recent solid stool, impaction should be considered. Constipation may be due to immobility or dietary intake (e.g. reduced fibre and fluid intake). Increasing dietary fibre, fibre supplements and stool softeners are the first line of management. The combination of ageing, other health problems and swallowing difficulties may increase the risk of complications associated with the use of emollients such as mineral oil, stimulants, osmotic agents and enemas. (Management of constipation is discussed in Ch 42.)

Carer support

Carer support

AD disrupts all aspects of personal and family life. Those caring for people with AD are at a high risk of anxiety and depression because of the high demands of caregiving and, in particular, the memory loss and behavioural disruption that is experienced by the patient with dementia.33 Interventions that can help carers to recognise and understand the disease process are provided in Box 59-5.

As the disease progresses, the relationship of the carer to the patient changes.25 Family roles may be altered or reversed (child caring for parent). A range of decisions must be made, including when to tell the patient about the diagnosis, when to have the patient stop driving or doing activities that might be dangerous, when to ask for assistance and when to place the patient in adult day care or long-term care. With early-onset AD, the patient is affected during their most productive career and family years. The consequences can be devastating for the individual and the family.

Sexual relations for couples are also seriously affected by AD. As the disease progresses, sexual interest may decline for both the patient and the partner. A number of reasons account for this, including carer fatigue, and memory impairment and incontinence in the person with AD. It is also possible for the person with AD to have a heightened sexual drive as the disease causes them to become disinhibited.

The nurse has an important role in working with the carer to determine stressors and strategies to reduce the burden of caregiving. For example, establishing what the carer views as most disruptive or distressful can help establish priorities for care. Establishing the carer’s knowledge of AD can assist the nurse to determine their education needs. Carer education can help to reduce conflict—for example, by teaching carers to understand that disruptive behaviours are a result of the disease.24 Risks to the safety of the patient and carer are given high priority.

Carers, most of whom are women, may be older adults themselves. The caregiving stress or burden can have adverse outcomes for their health, especially for those who have chronic health problems. Caring for someone with dementia can result in the carer feeling they are living within a cycle of continual loss.33 Nurses have a role in helping and supporting carers so that they can develop a sense of satisfaction and accomplishment within their caring role.

Support groups for carers and family members are available in both Australia and New Zealand within the various Alzheimer’s associations and carers support services. Such groups aim to provide an atmosphere of understanding and to give current information about AD and related topics, such as safety, legal, ethical and financial issues. Other supportive strategies include stress management and relaxation.

Other neurodegenerative diseases

Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease are neurodegenerative diseases (these are discussed in Ch 58). Both diseases are chronic, progressive and incurable. Despite differences in the aetiology and pathophysiology of these diseases, both are associated with the development of dementia in the later stages of disease.

Lewy body disease is a condition characterised by the presence of Lewy bodies (intraneural cytoplasmic inclusions) in the brainstem and cortex. The disease has features of both AD and Parkinson’s disease. Patients with this form of dementia exhibit disabling mental impairment progressing to dementia, fluctuations in cognitive function, visual hallucinations and features of Parkinson’s disease, especially rigidity. The diagnostic criteria for Lewy body dementia is based on clinical signs and symptoms and is confirmed at autopsy by histological examination of brain tissue.

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rare and fatal brain disorder thought to be caused by a prion protein. A prion is a small infectious pathogen containing protein but lacking nucleic acids.34 There are three types of CJD: sporadic CJD, hereditary CJD and acquired CJD. Worldwide, sporadic CJD affects 1 in 1 million individuals each year. The earliest symptom of CJD may be memory impairment and behaviour changes. The disease progresses rapidly with mental deterioration, involuntary movements (muscle jerks), weakness in the limbs, blindness and eventually coma. There is no diagnostic test for CJD. Only autopsy and examination of brain tissue can confirm the diagnosis.34 There is no treatment for CJD. Emphasis is on reducing the risk of acquiring CJD via food products.

A variant of CJD (vCJD; also called ‘mad cow disease’) was first described in the mid-1980s. The source of this infection appeared to be beef used in baby food preparations obtained from animals contaminated with bovine spongiform encephalopathy. Worldwide, approximately 110 cases of vCJD have been identified. No cases have been reported in Australia,35 but 6 people in New Zealand who received US-made made pituitary hGH were reported as having been diagnosed with CJD in 2010.36

Pick’s disease, a type of frontotemporal dementia, is a rare brain disorder characterised by disturbances in behaviour, sleep, personality and eventually memory.37 The major distinguishing characteristic between this disorder and AD is marked symmetrical lobar atrophy of the temporal and/or frontal lobes. The disease is relentless in its progression, which may ultimately include language impairment, erratic behaviour and dementia. Because of the strange behaviour associated with Pick’s disease and frontotemporal dementia, psychiatrists are often asked to see these patients before they are sent to geriatric services.38 There is no specific treatment. The diagnosis can be confirmed only at autopsy.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus is an uncommon disorder characterised by an obstruction in the flow of CSF, which causes a build-up of this fluid in the brain.37 Symptoms of the condition include dementia, urinary incontinence and difficulty in walking. Meningitis, encephalitis or head injury may cause the condition. If diagnosed early in the disease, normal pressure hydrocephalus is treatable by surgery in which a shunt is inserted to divert the fluid away from the brain.

The patient with Alzheimer’s disease

CASE STUDY

Patient profile

Dan Yves, an 80-year-old man, was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease 3 years ago. His 78-year-old wife brought him to the emergency department because he wandered from his home, fell and injured his left hip.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

1. What is the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease?

2. What precipitating factors may have resulted in this patient’s fall?

3. What precautions need to be taken regarding the inpatient care of this patient?

4. What teaching and discharge plan should be developed for this patient and his wife?

5. Write one or more appropriate nursing diagnoses based on the assessment data presented. Are there any collaborative problems?

1. Which of the following patients is most at risk of developing delirium?

3. Vascular dementia is associated with:

4. The clinical diagnosis of dementia is based on:

5. The early stage of Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by:

6. A major goal of treatment for the patient with Alzheimer’s disease is to:

1 Anderson D. Preventing delirium in older people. Br Med Bull. 2005;73–74:25–34.

2 Alagiakrishnan K, Blanchett P. Delirium. eMedicine from WebMD. Available at http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/288890-overview, Updated 3 January 2011. accessed 8 January 2011.

3 Broadhurst C, Wilson K. Immunology of delirium: new opportunities for treatment and research. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;179:288–289. (Seminal text)

4 Bjorkelund KB, Hommel A, Thorngren K-G, et al. Reducing delirium in elderly patients with hip fracture: a multi-factorial intervention study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2010;54:678–688.

5 World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. Geneva: WHO, 1992. (Still in current use)

6 Adams D, Sharma N, Whelan PJP, et al. Delirium scales: a review of current evidence. Aging Ment Hlth. 2010;14(5):543–555.

7 Ski C, O’Connell B. Mismanagement of delirium places patients at risk. Aust J Adv Nurs. 2006;23(3):42–46.

8 Cooke M, Moyle W, Shum D, et al. The effect of music on quality of life and depression in older people with dementia: a randomized control trial. J Hlth Psych. 2010;15(5):765–776.

9 Stagno D, Gibson C, Breitbart W. The delirium subtypes: a review of prevalence, phenomenology, pathophysiology, and treatment response. Palliat Support Care. 2004;2(2):171–179.

10 Access Economics. Caring places: planning for aged care and dementia, 2010–2050. Canberra: Alzheimer’s Australia; 2010. Available at www.alzheimers.org.au accessed 19 November 2010.

11 Access Economics. Dementia economic impact report, 2008. Wellington: Alzheimer’s New Zealand, 2008.

12 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). Residential aged care in Australia, 2003–2004: a statistical overview. Aged Care Statistics Series no. 20. AIHW cat. no. AGE 43. Canberra: AIHW, 2005.

13 Vogel T, Dali-Youcef N, Kaltenbach G, et al. Homocysteine, vitamin B12, folate and cognitive functions: a systematic and critical review of the literature. Int J Clin Pract. 2009;63(7):1061–1067.

14 Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state. A practical method of grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. (Seminal paper)

15 Alzheimer’s Australia. Dementia: a major health problem for indigenous people. Briefing prepared for Parliamentary Friends of Dementia. Paper 12. Canberra: Alzheimer’s Australia, 2007.

16 Australian Institute of Health & Welfare (AIHW). The health and welfare of Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Canberra: AIHW; 2005. Available at www.aihw.gov.au/publications/index.cfm/title/9226 accessed 8 January 2011.

17 New Zealand Ministry of Health (NZMOH) and the University of Auckland. Nutrition and the burden of disease: New Zealand, 1997–2011. Wellington: NZMOH; 2003. Available at www.moh.govt.nz/moh.nsf/indexmh/Publications-2003-Nutrition+and+the+Burden+of+Disease accessed 8 January 2011.

18 Abdul HM, Sultana R, Keller JN, et al. Mutations in amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 genes increase the basal oxidative stress in murine neuronal cells and lead to increased sensitivity to oxidative stress mediated by amyloid β-peptide (1-42), H2O2 and kainic acid: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2006;96(5):1322.

19 Xiong G, Doraiswamy PM. Combination drug therapy for Alzheimer’s disease: what is evidence-based, and what is not? Geriatrics. 2005;60(6):22–26.

20 Emre M, Bernabei R, Blesa R, et al. Drug profile: transdermal rivastigmine patch in the treatment of Alzheimer disease. CNS Neuro Ther. 2010;16:246–253.