THE GEOLOGICAL SLEDGE TRIP

BY DR. LAURENCE M. GOULD

IN his original plans for sledging operations southward from Little America, Admiral Byrd had expected to have the dog teams proceed directly south to the Queen Maud Range at the foot of Axel Heiberg Glacier. En route they were to establish bases that could be used by the airplanes for flights to the east or west as well as over the pole. The loss of the Fokker on the geological trip to the Rockefeller Mountains during the first season of operations necessarily curtailed the work that could be done by airplane. Of all places of interest, both geologically and geographically, the Queen Maud Mountains, especially at their junction with the supposed Carmen Land, had first place. With the loss of the Fokker it was impossible for the geologist to have a plane at his disposal to reach these fields of activity. Consequently it was decided to have the southern sledging trip provide the means for geological and geographical research in this section as well as to lay bases for possible use by the airplanes. The designation of the party was then changed to the Geological Sledging Party under the leadership of the expedition geologist.

To reach the places desired by the geologist it was necessary to plan for a much longer sledge trip than had been originally visioned. These plans were consummated and the long trip was made possible only because of the excellent cooperation of the Supporting Party whose work has been elsewhere described.

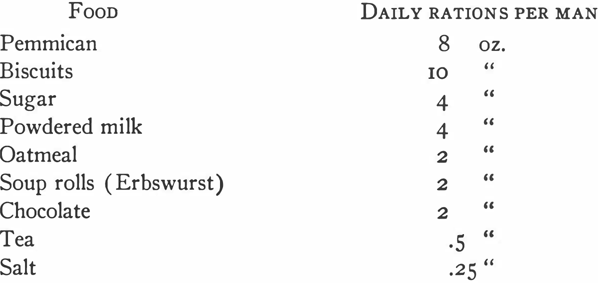

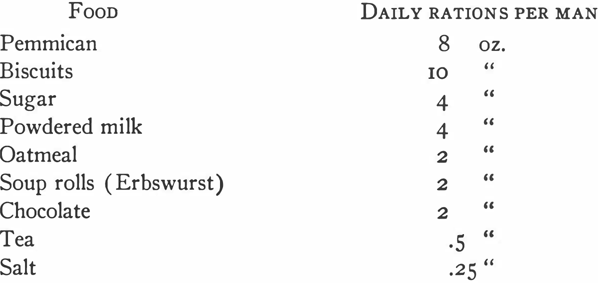

A large part of the winter was consumed in making plans and completing preparations for the trip. To understand the reasons for the success of the trip, a knowledge of these preparations is essential. The first thing to occupy our attention was, of course, food; and, with the assistance of Dr. Coman, we worked out the following very generous ration:

The above items were the essential constituents of our ration, but in addition, more or less as delicacies for occasional use to add variety, we included:

The greatest innovation in the above is oatmeal. It was necessary in preparing rations for such a lengthy trip to take food that needed little or no cooking, in view of the fact that our entire fuel supply had to be carried with us. We did some experiments during the winter and found that a vacuum jug made an excellent fireless cooker, and that it was only necessary to bring the oatmeal to a boil and put it into the jug after supper to find it well cooked by morning. Furthermore, after breakfast we filled the jug with hot tea so that we could make our noonday stop and have a hot drink without lighting a fire. This system worked out well, and throughout the summer we had two bowls of hot oatmeal and milk for breakfast with two cups of hot tea and a biscuit: for lunch, two cups of tea, a 4 oz. bar of chocolate and two biscuits: for supper, two or three bowls of rich stew made of pemmican and soup rolls, four biscuits and two cups of tea. The other items in our rations were used from time to time by way of variety.

For a cooker we used an adaptation of the Nansen cooker designed and built by Victor Czegka, the machinist. For the standard one burner primus, a two burner arrangement was substituted. I dare say no one has ever used a more efficient stove than this one.

Of almost equal importance to our own food, was that of the dogs. It was a rare bit of good fortune that Dr. Malcolm, Professor of Chemistry at Otago University in Dunedin, New Zealand, interested himself in our behalf. He designed a pemmican that represented a correctly balanced diet which the dogs liked and on which they thrived throughout the trip.

Little need be said about our personal equipment, for it did not differ essentially from that used by Admiral Byrd and others who went far afield by air.

The sledges came in for a good deal of alteration. We planned to have five dog teams of nine dogs each with each team hauling two sledges in tandem. When we finally left Little America we used for lead sledges, one single-ended flexible sledge, two double-ended flexible sledges, and two double-ended rigid freight sledges such as had been used so successfully in transporting supplies from the ships to Little America. For the second or trailer sledges we used much lighter types, two single-ended sledges supplied by Amundsen and three sledges with runners made from skis. We found the rigid freight sledges heavy and cumbersome to handle on the trail, and as our loads lightened these were the first sledges we abandoned. In every particular for use on the trail we found the flexible type—that is one bound together by rawhide thongs—superior. All of these flexible sledges which we used were lashed together by Strom and Balchen, and the two double-ended lead sledges were entirely constructed by them. I do not think that any explorers have had better sledges than these two.

In addition to the expected amount of camp gear, ropes and materials for making repairs, we carried a moving picture camera and six thousand feet of film, two still cameras with an abundance of film, a radio receiver and transmitter with hand generator, and flags for marking the trail.

We planned to mark the trail at half mile intervals with small orange flags. Surmounting each depot of dog food, man food and fuel to be laid down at fifty mile intervals from Little America to the foot of the Queen Maud Mountains, was to be a large flag. Furthermore a line of trail flags, spaced at one-fourth mile intervals, was to be placed to the east and west of the depots for a distance of five miles. The flag sticks thus set out were to be numbered serially beginning with one and proceeding away from the depot on either side. Flags to the east to have a capital E together with the appropriate number, while those to the west were to have a W with appropriate number. Thus a flag stick marked with W-2 would be eight flags or two miles west of the depot. For the first 200 miles of the trip southward, which ended with depot No. 4, this system of marking the trail and laying depots was carried out by the Supporting Party.

As our plans stood completed we planned to sledge directly south from Little America to the foot of the Queen Maud Mountains, where we would establish a base where Admiral Byrd could make a cache of gasoline and oil for refueling on the polar flight. After the polar flight we planned to scale Mt. Nansen, if possible, and then sledge eastward along the foot of the range, at least as far as Carmen Land. We were then to return to our base camp, established when we reached the mountains, and follow our trail back toward Little America as far as depot No. 5 at latitude 82° 35' south. We then proposed to leave the trail and head northeast to investigate Amundsen's recorded appearances of land, after which we would return to our main trail at depot No. 3, and then back to Little America.

Neither the Supporting Party nor the Geological Party found any evidence of this land on their way south. On his first flight south to lay a cache of gasoline and oil for the polar flight, Admiral Byrd found that there was no land whatever showing toward the east. The Geological Party therefore naturally abandoned its plan to leave the main trail when homeward bound. Otherwise the plans as outlined above were carried out.

By the middle of October both sledging parties were ready to depart. On the morning of October 15, 1929, the Supporting Party took its final departure. We decided to go along with them for a few days, just by way of testing out our own equipment and to have our heavy loads at least a few miles under way when we took our final departure. In my own unenlightened eagerness to be of use, I attempted, with my skis on, to drive Mike Thorne's team. The results were disastrous. My skis became entangled with dogs and sledges. I was so badly bruised as a result that I brought my own party back to Little America from only 20 miles out. Two days after our return to Little America the five dog teams departed again on what we termed the 100 mile trip. I remained in camp to recuperate. They moved our heavy loads out to depot No. 2, 100 miles south of Little America, and then returned to Little America, arriving on October 28th.

Some seven days were consumed in making desired alterations in our equipment and giving the dogs a good rest. Finally on November 4th everything was ready for our final departure. There were six of us—Frederick E. Crockett, dog driver and radio operator; Edward E. Goodale, dog driver; George A. Thorne, dog driver and topographer; J. S. O'Brien, dog driver and surveyor; Norman D. Vaughan, dog driver and in general charge of all the dogs; and myself in the role of navigator, cook, and of course geologist.

It was a dull gray day with overcast sky—at one P. M.—that we took our departure.

The first 100 miles, of course, were dead easy, for my companions had previously advanced our heavy sledge load to that point. From here south it was hard work Little need be said about our travel to depot No. 4, established by the Supporting Party at 81° 43', for they had traversed and marked this part of our route ahead of us. Their difficulties in crossing the badly crevassed area between 81° south and depot No. 4 have been described. The fact that they preceded us and marked the trail made our crossing relatively easy. Recrossing this area two months later on our homeward trip was, however, a different story.

We arrived at depot No. 4, the last outpost of the Supporting Party, on November 17th. From here on our work became heavier, and the dogs had already all the load they should haul. Yet somehow we had to carry on from here at least 500 pounds of dog food. We loaded it onto our sledges, and on the morning of November 18th we started southward pioneering our way.

We had long since learned that the dogs keep a straighter course if someone leads the trail ahead. George Thorne, or Mike, as we all called him, was eminently fitted to lead the way. Thus we travelled with Mike ahead, immediately I came driving his team so that I could watch the compass on the sledge and call ahead to him as necessary, “right,'' “left” or “steady.” He had such a good sense of direction that he needed but little steering from me.

This first day with the additional loads was a disheartening one. Everybody was tugging at ropes tied to the sledges trying to help the dogs along, and Mike and Norman even carried heavy packs on their backs. Even so we travelled but 8 miles. The mountains seemed infinitely far away that night. Our sense of slowness in travel was further accentuated that day, for just after noon we suddenly heard behind and above us an unfamiliar and unexpected roar. We looked up to see the Floyd Bennett soaring over us southward bound to lay a cache of gasoline, oil and food for use on the polar flight. A sharper contrast between the old and the new methods of travel could hardly be pictured. Here was Commander Byrd and his party covering in four hours a distance which took us four weeks to cover with our dogs.

November 19th we travelled 12 miles, and the dogs were so utterly tired out that we deemed it best to give them a holiday. Accordingly we let them rest the 20th. This was a good idea. From now on things began to go better. And from here on to the mountains we travelled along without greatly fearing but that we should be able to make our goal.

From the crevassed area to the mountains the Barrier is quite flat and unbroken. The following entries from my log describe typical days over this part of our journey: “Nov. 21. Fairly good surface this morning—few low sastrugi but well coated over. Overcast but with fair visibility this morning. Became steadily worse and at 10 o'clock a light snowfall began. The horizon promptly disappeared, and we are in that sort of milky light when every direction—up, down, left, right—all look alike. One could not even distinguish the snow surface at his feet. One had the curious sensation of being suspended in a world of opaque white. I became fairly dizzy watching the compass and then looking up to see if Mike was on the course. I would level my eyes toward him and then find him up above me 45 degrees, so it seemed.”

“November 25. Rough sastrugi which we had to cross diagonally and which made the compass bound about badly and steering, therefore, difficult. As is always the case, these sastrugi trend in an ESE to WNW direction. We were sure at noon that at last we could see the long sought for mountains. Shortly after noon, the southerly haze lifted and there to the southwest, but still very far away, was a grand escarpment of snow covered peaks, nothing dead ahead. By four o'clock we could distinguish a huge mountain mass almost dead ahead of us. This we believe to be Mt. Nansen. It has been a stimulating afternoon after the almost unchanging travel for the past three weeks over the sastrugi surface of the Barrier.”

“November 27. Twenty-five to thirty miles of wind this morning with heavy drift, but we would have gone on anyhow but that we were requested to wait until one P. M. for radio schedule with Little America to advise them about the weather, since they were in readiness to take off for the polar flight. Even so we broke camp immediately the schedule was over and were under way by three o'clock.

“The mountains have drawn much nearer today, so much so that it is hard to believe that they are still 50 miles away. Perfect weather this afternoon with only about 5 miles of wind, made the mountains stand out especially clearly. We could see a great gap in the solid wall of rock, which we believe to be Axel Heiberg Glacier, and we have already altered our course to steer directly toward it. (Later we were to learn that it was Liv's Glacier and not Axel Heiberg toward which we were steering.)

“The weather has been perfect since noon. Nothing better could be hoped for for the polar flight, but we learn that it is still cloudy and windy at Little America.”

“On the morning of the 28th I sent a message to Commander Byrd to the effect that the sky was cloudless, that the barometer was high, that there was no wind, and that this looked like the day.

“It was the day. We remained in camp or stood by for the flight, listening in by radio ready to start with our dog teams to the rescue should the plane have a forced landing. We were not needed, but we did get a real thrill when the Floyd Bennett, poleward bound, zoomed over us and dropped us a parachuted load of films, messages and cigarettes.

“November 29. Shortly after 9 o'clock, when we learned that the Floyd Bennett had landed at Little America, we broke camp and were under way again.

“The mountains stood out clearly and beautifully, and we continued to head directly for the great break which we at first thought was Axel Heiberg glacier, but which we are now convinced is Liv's. The mountains draw perceptibly nearer and it looks very much as though we would surely reach them tomorrow.

“November 30. The mountains looked so near that we decided to make them or bust—it came very near being the latter. We travelled 35 miles over the toughest going we have ever had, which was complicated by a twenty mile wind from the SE with heavy drifting snow that stung our faces and pushed us about where the surface became icy near the mountains. Fifteen miles away from the mountains the Barrier was pushed up into icy covered ridges by the ice flowing out of the glaciers, and the whole was cut up by a series of great, almost parallel crevasses, miles in length, that crossed our course diagonally. We crossed numberless ones—great huge ones—little ones—open and closed ones—bridges falling in as we hurried across.

“Individual dogs always tumbling in, and occasionally part of a team would fall through and begin to fight amongst themselves, and then again a sledge would break through.

“As we neared the mountains the surface became icy, and it became increasingly difficult to keep straight on skis and manage the sledges, but we are camped tonight at the foot of Liv's Glacier in the very shadow of Mt. Nansen. Very tired after the long trek, but even if I were not I should need much more poetic felicity of expression than I can muster to give any notion of the sublime sight ahead of us—a mighty range of mountains from ten to fifteen thousand feet high, rising sheer from the Ross Barrier, which at their feet are less than 300 feet above sea level. We already feel repaid for the long hard days of travel behind us—up every morning from 5:30 to 6 o'clock, with temperatures from 5 to 30 degrees below zero, start the primus stove to thaw out our food and melt snow for powdered milk and for tea. Then the dead quiet (provided the dogs have not begun to stir about) of the Barrier air is disturbed as I howl, ‘Breakfast! Norman, Eddie, Freddie, Mike, Obie.' Then breakfast of oatmeal, steaming hot from the vacuum jug, with plenty of rich milk and sugar, then two cups of tea and a biscuit. Breakfast over, great haste to get under way as soon as possible. We stop at noon for a few minutes rest and for two cups of hot tea from the vacuum jug, two biscuits, a bar of chocolate, and a small piece of pemmican. We mush on again until we think the dogs have gone far enough, halt, pitch our tents, picket and feed the dogs. While the others are busy attending to the dogs I am busy getting supper of thick pemmican stew, three biscuits with bacon fat, or, on rare occasions, butter and two cups of tea, and then into our fur sleeping bags. But now all that is changed, and a month, full of opportunity, lies right before us.”

Thus far in our travels we had concentrated entirely on the business of getting to the mountains. Now we were ready to go to work. There were two major tasks ahead of us. We wanted to map or chart as great areas of the Queen Maud Mountains as we could, and here before us lay a veritable paradise for a geologist. Naturally I wanted as much time as possible to devote to my geological and geographical studies. We made a division of labor with George (Mike) Thorne and Jack O'Brien assigned to the task of mapping while I was freed to devote myself to my own particular interests. I assisted with the mapping to the extent of doing the navigating and making all the astronomical observations. In the following weeks nothing seemed to please Mike so much as to stand around with his compass on a jacob staff or with the theodolite shooting angles on peaks and glaciers. He was tireless, and it was principally due to his industry that we were able to bring back so complete a map of our travels in and along the front ranges of the Queen Maud Mountains.

We spent three days exploring the lower part of Liv's Glacier and the surrounding mountains. We immediately saw the necessity of getting well into the mountains beyond the foothills if we were to reach the rocks that held the key to the geology. These foothills were composed entirely of the old pre-Cambrian rocks, the very oldest rocks we know, while the higher mountains farther south were seen to have their lower portions of old pre-Cambrian rocks overlain by some kind of flat-lying rocks that appeared to be arranged in layers. If these layers turned out to be sedimentary then we should be able to unravel in part the geological story of this great mountain range.

We had hoped to be able to get at these higher mountains by way of Liv's Glacier, but we found it so steep and so badly crevassed that we were scarcely able to climb it on foot even when shod with crampons. We therefore left this, our first mountain camp, and came along the foot of the range to the southeast and camped on the lower part of what Amundsen indicates on his chart as the western portion of Axel Heiberg Glacier. We established our mountain base here and called it Strom Camp, and immediately set to work making preparations for our projected trips into the mountains and eastward. The most important part of our preparations consisted of taking an accurate inventory of our dog and man food and basing our plans on the amount of food available.

Our first field work necessitated ascending the glacier to get at the rocks that capped Mt. Nansen, which lay at the head of it. We left Strom Camp on December 6th and sledged fourteen miles up the glacier and camped as near as we could to the rocks which I wanted to reach. The flanks of Mt. Nansen were encased in ice which in part pulls away from the rock faces to leave great crevasses which made the ascent to the rocks somewhat uncertain.

The next day Mike Thorne, Ed Goodale, Freddie Crockett, and I started out on skis to climb the steep slope above our camp and thread our way, if possible, among the crevasses to the rocks which were our goal. We dared not attempt to climb about here other than on skis for fear of falling into crevasses, and in my log for December 7th, I find the day described as follows:

“Climbed on skis up saddle between two spurs on southern slope of Mt. Nansen—very steep and difficult with a small ice falls half way up, a series of crevasses transverse to our course from one to eight or eleven feet in width, but usually roofed over. We roped to climb and ‘herringboned' and ‘sidebilled' our way up on our skis. Had to climb even steeper slope beyond these first crevasses to reach the coveted rocks—a bit hazardous this, for we were climbing along a steep side hill, and some 200 feet below us, paralleling our course, was a great yawning chasm.

“The snow was crusted over, and it was hard to make our skis stick, but we finally reached our rocks, the very rocks that I wanted most to find in the Antarctic. We became so interested in our rock collecting that none of us noted the changing weather. Quite suddenly we were completely engulfed ant could see nothing of our surroundings. We hastened to put on our skis, hoping we would be able to retrace our steps. Then it began to snow, and we began to get a bit nervous. We hurriedly roped and began our descent.

“Mike is an expert on skis, but for the rest of us the down going was more difficult than the ascent. We slipped and fell time after time, knowing the big open crevasse was a few feet below us, got up, swallowed our hearts, and skidded on again. Fortunately the snowfall was not sufficient to cover our tracks, and when we had cleared the first steep slope the clouds lifted enough so we could see our way across the worst of the crevasses. Then came the steep, uncrevassed slope with which we began our climb. Here we could take off our awkward ropes. Mike slid grandly down the hill and Freddie Crockett did pretty well following him, but as for Ed Goodale and me, after trying with great difficulty to sidehill our way down, we finally sat down on our skis and disgracefully slid to the bottom.”

This was really one of the worst days of the whole summer, and not the least significant of the thrills was the realization that the flat lying rocks that cap Mt. Nansen were a great series of sandstones, containing toward their top seams of impure coaly material. This discovery definitely establishes the fact that we are here dealing with precisely the same mountain structure as those known and studied by British geologists along the western borders of the Ross Sea. In other words the structure of the sandstone demonstrates that Mt. Nansen is part of a great uplifted fault block system of mountains, that takes its rise more than a thousand miles away toward the west and north. Furthermore the presence of the low grade coaly material on Mt. Nansen greatly increases the limits of the coal field that is believed to underlie a large part of the Antarctic Plateau.

It was also on this first day's climb that Ed Goodale found lichens on one of the rocks. It was an interesting find for it was the farthest south at which indigenous life of any sort had ever been found. We were later to find greater growths of lichens even farther south than this.

On the 8th of December we moved farther westward to get at another spur of Mt. Nansen, and Norman Vaughan, Ed Goodale, Mike and I climbed again to the rocks—up ice faces where we had to chop our steps and over ragged pinnacled columns of dolerite—lots of fun and amazingly interesting rocks.

Another day's work about this side of Mt. Nansen, and then we headed back down the glacier to make preparations for our trip eastward along the foot of the range. What a riot it is driving the dog teams down the steep slopes of the glacier. The sledges are rough-locked, that is, ropes are put around the runners to prevent their sliding easily, and then the driver yells ‘'yake" and tries to keep his team from getting too near another one and away from any chance crevasses.

Coming down Norm's team and Eddie's got too close together and mixed in one grand fight. I was sliding grandly along between the sledges. Immediately the fight commenced, and purely from the standpoint of self preservation, I tried to stop, but instead I slid right into the middle of the mêlée and in trying to extricate myself from the jam without getting bitten I parted the dogs and have not yet confessed to the drivers that I did not deliberately set out to separate the dogs for them. I am such an awkward dog driver anyhow, that when I make a grand splurge like this one I hate to confess that it was accidental.

Before returning to Strom Camp we climbed what we believed to be Mt. Betty, both to make a search for a cache left there by Amundsen eighteen years ago, and to get a look up the eastern part of Axel Heiberg Glacier. We failed to find the cache and did not get much of a view of Axel Heiberg. We returned to our base camp to make ready for our proposed eastern trip. On the 12th Ed Goodale and I made a successful search for the cache of food and gasoline laid down by Admiral Byrd before the polar flight. We brought the food back to camp and were glad to have it, for it gave us a great margin of safety for carrying out our plans without taking too long chances.

On the morning of the 13th—and it was Friday too—we started on our eastern trip. To our left the Barrier was heavily blanketed with clouds, but it was brilliant sunny weather over the mountains, and what a setting for our start! Ahead and disappearing toward the east a great range of mountains unknown and unexplored—fifteen miles away and to our right was Mt. Nansen in all his glory. A great sight is this mountain, dignified and grand as befits anything named for such a man as Fridtjof Nansen.

We camped part way up Axel Heiberg Glacier with Mt. Ruth Gade towering above us—a fairy land setting in this world of white in the brilliant sun. How different it was the next morning—sky overcast and snow beginning to fall. For three days we were snowbound, with a fall of sixteen inches of soft wet snow, and so warm that it melted on everything it touched. We were wet and, of course, very cold, much colder than we had been at 25 below when we could keep dry.

Time hung heavy on our hands. When we left Little America each man was allowed to bring one book, but of course these had been left at Strom Camp when we started eastward. Someone had brought a pack of cards, so we played hearts with our daily issue of chocolate for stakes. How different our camp looked when the sun finally came back. The dogs, as they lay curled in the snow, had melted themselves down into wells. They were half buried, and the tents, sagging under their load, reminded one of evergreens at home with their branches sagging after a heavy fall of wet snow.

On the 7th when the sun returned, we dug ourselves out and were under way again—very heavy sledging and skiing. Directly ahead of us the surface was so badly crevassed that we had to head out into the Barrier to go eastward. We made frequent stops for Obie and Mike to do their surveying. About two o'clock on the 18th we saw that we were coming to a great ice field and decided to turn sharply to our right and go into the mountains and climb up for a look around. We camped at the foot of an interesting looking ridge up which we climbed 2,000 feet after supper. An observation later showed this to be our farthest south, 85° 27', and even here as at Mt. Nansen we found lichens on the rocks, the farthest south that life has yet been found.

The mountains here were composed entirely of the old pre-Cambrian gneisses, schists and granites, the very oldest rocks known. There was no cap rock of sandstone. The great sheets of ice that had at some not very remote geological time covered all these mountains, had long since carried it all away. But any rocks are of interest to the geologist—and all the members of the party had by this time become amateur geologists—so of course they were ever on the outlook for minerals. In general these old rocks were quite barren of interesting minerals. It was about this camp that were found some copper bearing rocks but not in sufficient quantity to suggest any extensive deposits.

We looked out away from the mountains and to the east, and the surface was ice as far as we could see. But we had decided to go eastward, at least as far as Marie Byrd Land which begins at the 15t0h meridian. In my log for the 19th I find that “We headed out to avoid the ice, but it was no use—soon became so bad that we couldn't stand on our skis but had to take them off and hang onto the sledges. Ice was fairly smooth at first, but after two hours travelling we found ourselves in an area that had been much crevassed. Fortunately most of the crevasses were not of great extent, but they gave us some nasty spills nevertheless. We had to play a sort of game of tag with them. We could see them easily enough, for they were in part bridged with snow, whereas the rest of the ice was swept clean. But seeing the crevasses and avoiding them were two different matters.

“It was almost impossible to guide the sledges or make the dogs go where we wanted them to go. The dogs have gotten pretty smart about crossing crevasses and have learned that their best chance of keeping out is to head straight across them. But once they are across they forget that a change in their course may pull the sledge into the very hole they have been able to avoid. So we often crashed into them with our sledges. Wrecked one of our best sledges and had to abandon it and badly damaged the runners on the others. We had to travel 25 miles before we could find a patch of snow big enough to anchor our tents on.”

It was the same thing over again the next day, but most of the time we were going down hill so we made another 25 miles to find ourselves well to the east of the 150th meridian—in Marie Byrd Land—on American soil here in the Antarctic.

Here again we found the same old rocks that form the base of all the mountains and constitute all of the mountains except the great high ones around Axel Heiberg Glacier, where these old rocks are overlain by the sandstone. Here also we found the same fault block structure.

Looking back over the route we have come and the area we have mapped it is interesting to note that eastward from Mt. Alice W. the mountains are much lower and continue so as far east as we could see. The highest peaks in Marie Byrd Land do not exceed 5000 feet, while Mt. Ruth Gade beside Axel Heiberg Glacier is 15,000 feet. This eastern part of our mountains is also characterized by greater glaciers than Axel Heiberg or Liv's. We charted three great valley or outlet glaciers that should be classed along with the Beardmore which is the largest valley glacier so far known any place in the world.

While Mike was busy finishing his mapping the rest of us climbed the nearest mountain. We called this one Supporting Party Mountain. It was our farthest point from Little America and we had been able to reach it only because of the good work of the Supporting Party. We built a cairn on top of the mountain. In this cairn will be found a page from my notebook with the following note thereon.

“Dec. 21st, 1929

Camp Francis Dana Coman

85° 25' 17" S

147° 55' W

Marie Byrd Land, Antarctica

“This note the farthest east point reached by the Geological Party of the Byrd Antarctic Expedition. We are beyond or east of the 150th meridian, and therefore in the name of Commander Richard Evelyn Byrd claim this land as a part of Marie Byrd Land, a dependency or possession of the United States of America. We are not only the first Americans but the first individuals of any nationality to set foot on American soil in the Antarctic. This extended sledge journey from little America has been made possible by the cooperative work of the Supporting Party composed of Arthur Walden, leader; Christopher Braathen; Jack Bursey; and Joe de Ganahl. Our Geological Party is composed of:

L. M. Gould, leader and geologist

N. D. Vaughan, dog driver

G. A. Thorne, topographer

E. E. Goodale, dog driver

F. E. Crockett, dog driver and radio operator

J. S. O'Brien, civil engineer.”

When I had collected all the rocks I thought we could carry and Mike had finished locating his mountains and glaciers we were ready to start back toward Strom Camp. The essential part of our scientific work was finished. We had mapped 175 miles of the front ranges of the Queen Maud Mountains, we had demonstrated that this great fault block mountain system is continued almost due eastward from Axel Heiberg Glacier for more than a hundred miles, we had demonstrated that there is no such highland as Amundsen thought he saw and called Carmen Land, and furthermore we had helped to push the known limits of the Ross Shelf Ice more than one hundred miles east than they had been known to exist by the base laying flight made by Commander Byrd.

Westward bound toward Strom Camp we found recrossing the glacial ice almost as much of a nightmare as it had been the first time we had crossed. Otherwise the return journey was devoid of special happenings until we camped Christmas Day at the foot of Mt. Betty. We had determined to make a last thorough search of this mountain for the Amundsen cache, for there was no other place that would fit Amundsen's description of Mt. Betty. As we broke camp, Mike and I skied ahead down to a ridge where we thought we saw something that looked like a cairn of rocks. It was.

We signalled the dog teams to come along. What a thrill we did all get on this Christmas Day to stand where Amundsen had once stood and to find, perfectly intact, the cairn he had erected eighteen years before. We couldn't help standing at attention, with hats off, in admiring respect for the memory of this remarkable man before we touched a rock of the cairn. It was one of the most exciting moments of the summer when I pried the lid off the tin can in the cairn and took out a bit of paper which had formerly been a page in Amundsen's notebook, and on which he had briefly recounted his discovery of the South Pole.

Back in Strom Camp again on the 26th. I had wanted to make one more journey into the mountains but the dogs were too tired. We had to give them a few days rest before we began our long trek northward to Little America. We carefully overhauled our gear and discarded pretty much everything except our instruments, our food, and my rock collection. Our good discarded equipment we cached on Mt. Betty not far from Amundsen's cairn. In a tin can within the cairn we left a note giving a brief account of the Expedition and the Geological Party. I left one of my rock hammers on top of the rock cairn we had built around the cache.

On our homeward trip we decided to travel at night, both in order to have the sun behind us and because the sledging and skiing would generally be better than in the day. We had no relish for recrossing the crevasses in front of Liv's Glacier, so we laid our course northeast from Strom Camp hoping to avoid them and to pick up our trail later when we were all out into the solid Barrier again. For several days clouds had hung over the Barrier and mountains, but as if for a good omen they lifted just as we were ready to leave Strom Camp at one o'clock on the morning of the 30th.

Could you who read this have seen the picture that greeted us then, you would know that there had been much beside our geology and cartography to make the summer fascinating. To the south of us lay Mt. Nansen in all his splendor, his cap of shining ice, his blackish shoulders of bare rock loosely wrapped in a ragged old shawl, and the whole made glorious by the touch of the long skeletal fingers of the early morning sun.

This grand old mountain had somehow come to hold the first place in our affections, and this sight was just what we would all have wished to keep as our last intimate view of the mountains. We finally turned our backs and headed northward toward Little America and home.

Quite as we had planned we did miss the worst part of the crevassed area we had crossed when we had arrived at the mountains, and on the second day of travel we picked up our old trail. How much more easily we travelled along now than when southward bound. We had become much more adept on skis and the dogs were fairly lightly loaded.

Two things furnished the principal variety on the homeward trip until we were again in the crevassed region between latitudes 81 and 82. These were the weather and the character of the Barrier surface as it affected sleding and skiing. For January 3rd I find the following entry in my log:

“Now the morning sun is out and the sky is gorgeous with a great variety of ethereal cirri, and there is a bit of wind from the southeast. It has been overcast and foggy the whole night and most of the morning. In fact late in the morning there was a light fall of fluffy snow as though ‘the angels were moulting!' We had to keep close together to keep each other in sight, and even then it frequently happened that we with the front sledge could not see the last sledge behind us. I had to watch the compass fairly closely and call directions to Mike occasionally in order to keep on the course. And I don't believe we missed a single flag that we had previously placed to mark our trail. The thorough marking of the trail on our southbound trip was a good idea, and is already repaying us for the time we spent in doing the work.

“We came by depot no. 6 shortly after noon and stopped only long enough to take on some dog pemmican and some man food.”

And on the 4th the following: “Much hardest day we have had since leaving the mountains. Weak crust on the snow broke through under the dogs who plodded and waddled heavily along hauling sledges that went crushing their way through the snow rather than gliding over it easily. The dogs are already quiet. There will be no fighting amongst them tonight for they are very tired. A thin streak of clear sky to the south about midnight gave us one last glimpse of the snow capped mountains which are now far behind and which none of us will likely ever see again.”

We didn't need to worry about the weather until we reached the crevassed region. On January I oth the sky was overcast and things were pretty completely hidden from our view by a light fog. And we were nearing the broken area. I carefully watched the sledge meter and at what I thought was the proper time I said, “We'll camp here.” We had the usual experience that we had encountered before in areas where there is active deformation of the ice.

There was an almost constant fusilade as of rifle shots about and under us as the ice cracked under its tension. But in the middle of the night after the dogs and camp had been quiet for several hours I woke up and lay awake for a long time without hearing a sound. But when we got up in the morning and began moving about, the noises began all over again. Even though the Barrier is here some hundreds of feet thick, it appears that where we camped it was under such a delicate state of stress that our movements disturbed the equilibrium. When the clouds lifted we found that we had accidentally camped just between two goodly sized crevasses, either one of which we might easily have fallen into without skis.

We had to abandon our former trail through the crevasses on account of the roofs of old ones on the former trail having fallen in and new ones having formed. We travelled three miles and had to stop on account of heavy fog. We waited two days for it to clear but it lightened only partially. Our dog food was getting so low that we could not stay longer without killing some dogs. We didn't want to do that, so Norman, Mike, and I roped and started out on skis in an attempt to find a route we could follow out with safety. This we were able to do and hurriedly retracing our steps we broke camp and headed out. The next day we picked up our old trail just south of depot no. 3 as we had planned to do.

The rest of the homeward journey was uneventful. On the 19th, in the early morning, we saw the tops of the radio towers at Little America. Only then did we have the feeling that we were nearly home—home from a sledge trip on which together with our many side trips we had covered more than 1500 miles. Glad as we were to be back in the comparative luxury of Little America, it was with a feeling akin to the forlorn that we looked back at our sledge tracks disappearing into the limitless white to the south. We had had a good time and had, in some measure, known the joy of achievement.