At 6 inches, the wingspan of North America’s largest butterfly, the giant swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes, above), is nearly twelve times that of the continent’s smallest, the western pygmy-blue (Brephidium exilis, below).

In an increasingly altered and fragmented global landscape, butterflies are suffering from lack of flowers. Yards, gardens, and parks are often filled with turfgrass or cultivars that are beautiful to look at but provide no food for these insects. Habitat on farms has decreased as farmers seek to maximize production, and areas like roadsides are often mowed right when the flowers start blooming. Large quantities of pesticides are also used in all of these landscapes.

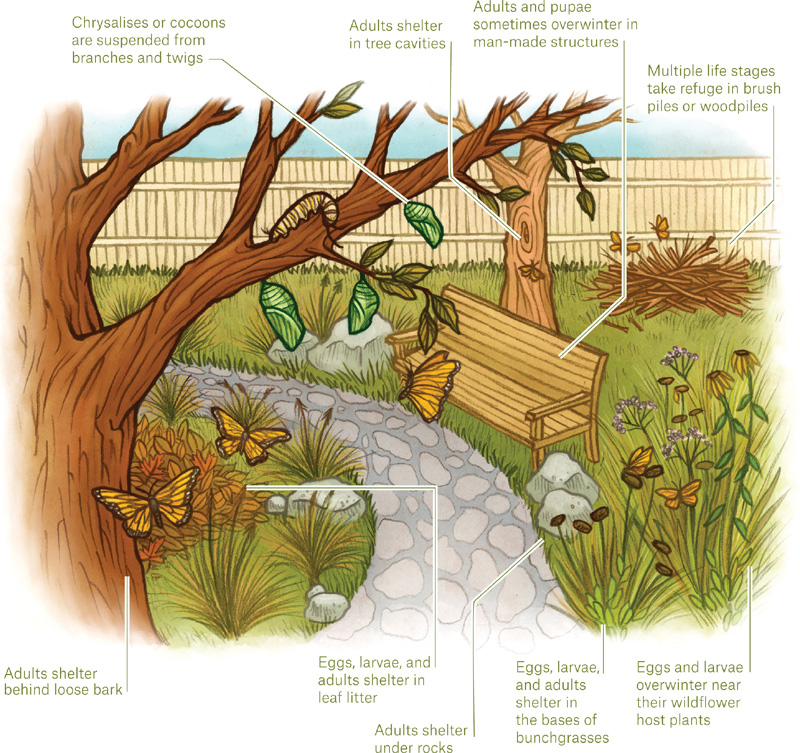

A well-designed garden can offer all a butterfly or moth needs to complete its life cycle. Providing host plants and nectar sources will go a long way toward attracting and keeping butterflies and is a very good place to start your butterfly gardening efforts. Adding sites where butterflies and moths can overwinter will round out your garden and make it truly a butterfly paradise. Knowing about the variety of butterflies that exist and the life stages of these animals will allow you to tailor your garden to their needs.

To help you know the butterflies you see in your garden, we introduce you here to the broad groupings of butterflies known as families, some of which are broken down further into subfamilies. Although representatives of most of these groups can be found in all areas across North America, the species you see will vary depending on where you live. To identify specific butterflies, we encourage you to check out one of the many good national and regional guides to butterflies that can be found in bookstores and libraries (some of which are listed at the back of this book).

At 6 inches, the wingspan of North America’s largest butterfly, the giant swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes, above), is nearly twelve times that of the continent’s smallest, the western pygmy-blue (Brephidium exilis, below).

The rapid, skipping flight of these butterflies gives the family its common name. Skippers are small to medium size and are distinct from other butterflies in having larger bodies in proportion to the wings. They can also be distinguished from other butterflies by the hooked bulb at the end of each antenna. On skippers, this bulb is bent almost 90 degrees to the side, rather than straight as in other butterflies.

Most North American species are grouped in one of two subfamilies: the monocot (grass) skippers and the dicot (flowering plant) skippers. There are approximately 200 species of skippers in the United States. You can encourage them to visit your garden if you provide their grass host plants.

Grass skippers often hold their wings partially open with the forewing separated from the hind wing, making two Vs.

GRASS SKIPPERS (SUBFAMILY HESPERIINAE) Grass skippers resemble moths, being hairier and more robust than most other butterflies, but unlike most moths they fly during the day. These skippers tend to have short wings and must flap them rapidly (“skip”) to fly. Most North American species are orange-brown and lack the brighter colors and complex wing patterns of the other butterflies, although this is not true of tropical species. When at rest, they often hold their wings partially open with the forewing separated from the hind wing, making two Vs, one inside the other, when observed from the front or back. Males of many species have dark patches or streaks on the upper side of the forewing containing special scales that produce pheromones for attracting a mate. Skipper caterpillars frequently curl the blades of grasses or sedges with silk to form nests in which they feed, overwinter, and pupate.

Dicot skippers are often dark and mothlike, as exemplified by this common sootywing (Pholisora catullus), but still have the clubbed antennae characteristic of butterflies.

DICOT OR SPREAD-WINGED SKIPPERS (SUBFAMILY PYRGINAE) Perhaps three dozen dicot skippers such as duskywings and cloudywings are native in North America. Dicot skippers are usually darker than grass skippers, either black or dark brown and often with white spots or checkers. They have broad wings that are commonly opened flat—not in the double-V pattern—when the butterflies are perched, hence “spread-winged” skippers.

The swallowtail family includes the largest and most easily recognized butterflies in the world, which are also among the most common butterflies seen in gardens. There are about 550 species worldwide. The aptly named giant swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes), with a wingspan up to 6 inches, is the largest butterfly in North America.

Swallowtails are well loved because of their size and beauty, and several species are formally recognized as state symbols. The eastern tiger swallowtail (Papilio glaucus) is the state insect of Virginia and the state butterfly of Georgia, Delaware, and South Carolina. The black swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) is the state butterfly of Oklahoma, and the Oregon swallowtail (Papilio oregonius) is the state insect of Oregon.

The wings of swallowtails are often black and yellow or black and white. Most species have tails on their hind wings reminiscent of the elegant forked tails of barn swallows and other similar birds. These tails may serve as a way to escape predators such as birds. When a bird strikes, it often takes off just the end of the tail on the wing of the butterfly, which does no real harm. Next time you see a swallowtail in your garden, look to see if it has escaped a bird.

The related parnassians (subfamily Parnassiinae) do not have tails and are often mostly white with red spots and only small, fine black stripes. The wings are often off-white or ashen because parnassians have a thinner covering of scales on the outer half of their wings, making them translucent and the colors less intense. Five species of parnassians are found in North America.

Adult swallowtails are strong fliers and may pass over your garden as often as they stop in it. In open areas and parks, they often patrol back and forth along the edges of wooded areas or streams. Some species gather in large groups at mud puddles and damp stretches of sand. These are mostly males who sip at the moisture to glean salts and other nutrients not available from flowers.

Swallowtail larvae are excellent mimics, and young caterpillars of some species mimic bird droppings with extraordinary accuracy as a means of camouflage. When disturbed or handled, older caterpillars of some species have an impressive defensive display: a bright orange, forked, foul-smelling organ called an osmeterium is pushed out just behind the head. The osmeterium likely startles predators, and the smell may deter them.

Caterpillars of some species of swallowtail display a bright orange, forked, foul-smelling organ called an osmeterium to ward off predators.

Swallowtails get their name from the tails on their hind wings, reminiscent of the elegant forked tails of barn swallows.

Whites like this Sara’s orangetip (Anthocharis sara) often have bright orange wingtips and black marginal wing patterns.

Male sulphurs are often a bright, clear lemon yellow like this orange sulphur (Colias eurytheme), while females are more likely to be off-white.

Butterflies in this family vary in size from small to swallowtail size and are most often white, marbled, yellow, or orange. Bright orange wingtips and black marginal patterns are common. In some species, the males and females have visibly different wing patterns or coloration. Males can be a bright, clear lemon yellow, while females are off-white with small dark markings. Some say that the word butterfly originated from a European member of this family, the brimstone (Gonepteryx rhamni), which centuries ago was called the butter fly in Britain for its pale yellow color.

In many areas of North America these are among the earliest butterflies to emerge, so they are the first ones to look for in early spring. They fly in a continuous fluttering pattern and are common along roadsides, in meadows, and in gardens. Sulphurs can be particularly quick moving, spending only a moment at a flower before flying on. Dozens of individuals, usually male, often group together on a patch of damp mud to drink and take in minerals and salts.

Larvae of most whites feed on the plants in the mustard family such as cabbage, and most sulphurs feed on plants in the pea family. Although very few butterfly caterpillars are pests, this family includes two: the orange sulphur (Colias eurytheme), which can be a pest of alfalfa, and the cabbage white (Pieris rapae), introduced from Europe and now one of the most common butterflies in gardens and a likely pest if you grow cabbage or broccoli. The widespread abundance and distribution of the cabbage white is not typical of this family, as many whites and sulphurs have restricted ranges and their caterpillars occur only on specific host plants.

The family Lycaenidae is a highly diverse group of small butterflies. The group includes the blues, coppers, hairstreaks, and metalmarks. It is the second largest group of butterflies, with approximately 5000 species worldwide and about 150 species in North America. Despite their small size, they are often strikingly beautiful, with wings shimmering in blue, green, or copper. Rather than being pigmented, the wing scales on male lycaenids have a structure that refracts light, leading to iridescent colors that change with the angle of viewing. The females are less brightly colored. On the underside, the wings of both males and females may be dotted with bold spots or zigzag lines.

As illustrated by this Melissa blue (Plebejus melissa), blues are small, usually less than 1½ inches across, but stunningly beautiful, with shimmering wings that are often dotted with bold spots or zigzag lines.

Damage to the wings of butterflies from bird strikes is relatively common. This gray hairstreak (Strymon melinus) survived thanks to wing markings that fooled the bird into striking the wrong end.

Many of these butterflies have hairlike tails and bright eyespots at the rear of their hind wings. Together, these mimic the head and antennae, an adaptation intended to fool predators such as birds; they strike the wing instead of the head, getting nothing but a mouthful of dry, scaly wing and allowing the butterfly to escape, torn but essentially unharmed.

This group includes the smallest butterfly in the United States (and one of the smallest in the world), the western pygmy-blue (Brephidium exilis), which measures little more than ½ inch from wingtip to wingtip. Blues are common residents of gardens in many areas of the country. Plants in the buckwheat family and the heath and heather family as well as shrubs such as dogwood, elderberry, and huckleberry can help attract them.

Many butterflies in this family, including blues and coppers, have an unusual relationship with ants. In some species, caterpillars feeding on the host plant are attended to and protected by ants, and the ants receive sugar-rich honeydew produced by the caterpillars in return. With particular species of ants, only the first part of the caterpillar’s life is spent on the plant, and the remainder of the caterpillar life span is spent in the ant nest. Once the ants bring the caterpillar into the nest, they may feed it ant regurgitations, or in some cases the caterpillar eats the ant larvae. Some ants bring the chrysalis up out of the nest; others let the butterfly emerge from the chrysalis inside the nest, in which case the butterfly must crawl out of the nest before it can expand its wings.

Nymphalidae is the largest and most diverse butterfly family, encompassing many of the best-known butterflies, such as monarchs and painted ladies. The family also includes fritillaries, crescents, checkerspots, anglewings, admirals, and longwings. They are called brush-foots because the forelegs of these butterflies are greatly reduced in size and covered in hair—brushlike. They are held close to the head and are used primarily for tasting potential food. Because the forelegs are so small and tucked away, these butterflies appear to have only four legs.

The great diversity of butterflies in this family means no single characteristic—other than the appearance of having only four legs—unites them or makes them easy to identify as a group. The nymphalids are often colored in shades of orange, brown, and black, sometimes checkered or dotted, sometimes having eyespots or spots of silver. Some are even shaped and patterned like dead leaves. Nymphalid caterpillars feed on a wide variety of plant families. Most caterpillars in this family have large spines, and their chrysalises are usually sharply angled and adorned with silver or gold colors.

Many caterpillars in the family Nymphalidae have large spines, as illustrated by this variegated fritillary (Euptoieta claudia).

LONGWINGS AND FRITILLARIES Longwings are tropical butterflies that breed on and are closely co-evolved with passionflowers. They are among the few butterflies to feed on pollen. Most species have long, narrow wings with stripes of color. The zebra heliconian (Heliconius charithonia) is the most widespread in the United States. It is commonly seen in Florida but may be found as far west as California and as far north as North Carolina. In contrast, fritillaries are widespread throughout North America and can be found in many different environments. The wings of fritillaries are orange or warm brown with black markings and often have glistening silver spots below.

The zebra heliconian (Heliconius charithonia) is a longwing that can be seen throughout much of the southern United States from Florida to California.

CHECKERSPOTS AND CRESCENTS As the name suggests, checkerspots often bear a checkerboard-like pattern in black, white, and orange. They are usually medium size (wingspan less than 2½ inches) and are relatively strong flyers. The crescents are generally smaller and typically have dark, crescent-shaped bands along the edges of their wings. This group includes some of our most endangered butterflies. On the West Coast, three closely related subspecies, the Taylor’s checkerspot (Euphydryas editha taylori), the bay checkerspot (Euphydryas editha bayensis), and the Quino checkerspot (Euphydryas editha quino), are all protected under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. Two other members of this family, the Baltimore checkerspot (Euphydryas phaeton) in the east and the Sacramento Mountains checkerspot (Euphydryas anicia cloudcrofti) in New Mexico, also need conservation attention.

The appearance of having only four legs is a defining characteristic of the brush-footed butterflies. The “missing” legs of this Baltimore checkerspot (Euphydryas phaeton) are the same orange color as the others and can be seen held close to the head.

Crescents like this pearl crescent (Phyciodes tharos) typically have dark, crescent-shaped bands along the edges of their wings.

TRUE NYMPHS (ANGLEWINGS, COMMAS, TORTOISESHELLS, LADIES, BUCKEYES, AND ADMIRALS) As strong fliers that travel broadly across the landscape, true nymphs include many butterflies that frequent gardens. They are almost all medium size but are highly variable in shape and color (as the long list of names here might suggest). The anglewings, commas, and tortoiseshells are remarkable mimics of bark or leaves, with the camouflaged underside of the wings completely masking the brightly colored upper side when closed together. Anglewings enhance this camouflage by having uneven edges to their wings; tortoiseshells have broader wings with less-ragged edges. The commas often have a silvery white, comma-shaped mark on the ventral hind wing. The ladies—including the painted lady (Vanessa cardui)—are strong fliers with orange or pink-tinted wings tipped with black and white. The underside is predominantly covered in intricate patterns in brown and cream with a line of obvious spots. The buckeyes, as you might expect, have large eyespots on their wings. The admirals are larger than the other true nymphs, with bold bands of white or orange that resemble the stripes of military uniforms.

The American lady (Vanessa virginiensis) is a frequent visitor to gardens.

The admirals, exemplified by this red admiral (Vanessa atalanta), are relatively large butterflies with bold bands of white or orange said to resemble the stripes of military uniforms.

SATYRS, BROWNS, AND RINGLETS Members of this group are medium size and often drab. They are usually various shades of brown and often have darker eyespots on their wings. They have a weak, bobbing flight and can be seen near woods, prairies, or alpine areas among grasses, which are their larval host plants. They also feed on bamboo and palms.

The satyrs, browns, and ringlets are not the most colorful butterflies but have a subtle beauty, as shown by this common wood-nymph (Cercyonis pegala).

MILKWEED BUTTERFLIES The milkweed butterflies include our best-known and best-studied butterfly, the monarch (Danaus plexippus). This familiar species is a remarkably strong flier, migrating great distances every year to overwintering roosts in California and central Mexico. Monarchs have a very interesting life cycle (more on this later when we discuss migration), and gardeners can take advantage of the fact that they spread out across the United States every year to draw them to gardens. This group also includes numerous other, mainly tropical, equally large species. In the southern United States, the queen butterfly (Danaus gilippus) can easily be mistaken for a monarch. This butterfly also feeds on milkweed and is only slightly smaller, with similar orange and black markings. Looking at how the markings are arranged and oriented allows for positive identification.

The queen (Danaus gilippus, top) is often mistaken for a monarch (Danaus plexippus, bottom). They are closely related and both feed on milkweed as caterpillars.

The life cycle of a butterfly is a miraculous phenomenon. Whereas the young of mammals and birds look like small versions of the adults, butterflies and moths go through a major transformation that restructures their entire bodies. Who would dream that a slow-moving, fat, crawling, leaf-chewing caterpillar could transform into a flying, nectar-drinking, colorful adult butterfly?

To achieve this transformation, a butterfly or moth passes through four distinct stages: egg, caterpillar (or larva), chrysalis (or pupa), and adult. An entomologist, or insect scientist, would describe this as complete metamorphosis because the form the butterfly takes is different at each stage. Compare this with simple or incomplete metamorphosis, in which the animal does not have a pupal stage and once hatched from an egg looks very much like it did at every prior life stage as it grows. Grasshoppers and shield bugs are examples of creatures that go through incomplete metamorphosis.

Some butterfly species (known as univoltine species) produce only one generation or brood per year, while many complete two or more generations per year. In each generation, an adult butterfly lays its eggs and the caterpillar grows and pupates and emerges as an adult. With two generations, this happens twice over the growing season. Generations from eggs laid during the spring or summer will complete their life cycle within three to eight weeks; those generations from eggs, larvae, or pupae that overwinter may take six to eight months. Regardless of the season in which breeding occurs, univoltine species take twelve months to complete their life cycle.

The butterfly and moth life cycle has four distinct stages—egg, caterpillar (or larva), chrysalis (or pupa), and adult—as illustrated by the Taylor’s checkerspot (Euphydryas editha taylori) butterfly. A well-designed butterfly garden provides for all of these life stages.

Butterfly eggs are singularly beautiful objects. Without a hand lens, you may see them as colored specks on a plant. Up close, they may be smooth and shiny or intricately structured with ridges or bumps, and may be spherical, flattened, or elongated. They may be white or yellow, green or red, and may have colored bands or spots. Some resemble tiny sea urchins, others currants and gooseberries. The eggs can vary quite a bit in size, shape, and color from family to family and even species to species.

Depending on the species, a female butterfly may lay a few dozen to many hundreds of eggs in her lifetime. She carefully selects particular plants, called host plants, on which to lay her eggs, singly or in clusters. She will most often deposit her eggs on the undersides of leaves, alighting on the leaf and curling her body to lay eggs from the tip of her abdomen. Eggs may also be laid on flower buds, stems, or, in the case of the Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae), on the tendrils of their host plant (the passionflower vine).

How long the eggs remain unhatched varies with the species. Some butterflies, such as many blues and hairstreaks, overwinter as eggs. For these species, the eggs last many months. For butterflies that lay eggs in spring or summer, development begins immediately and the eggs usually hatch after a few days.

Tucked underneath leaves or on plant stems, butterfly eggs can be hard to find, but you’ll be rewarded with the sight of intricate jewels. Eggs of different species often differ in shape, size, and color.

The Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) lays its eggs directly on tendrils of the passionflower vine.

The first thing newly hatched caterpillars do is eat, starting with their own egg shells—a good source of protein to jump-start their rapid growth—and then the plant on which the egg was laid. Caterpillars spend most of their time eating, and because they are particular about what they eat, it is critical for the adult female to lay her eggs on or very near an appropriate food source lest her offspring starve. Caterpillars can consume a tremendous amount of biomass relative to their size and ultimately grow to many times their original proportions.

Butterfly and moth caterpillars need to shed their skin to be able to grow. This Gulf fritillary (Agraulis vanillae) caterpillar has just molted; its freshly shed skin is behind it.

Like most insects, butterflies have an exoskeleton, even as caterpillars. This exoskeleton is basically their bone structure, a hard shell on the outside of their bodies with corresponding organs and muscles underneath. Because the exoskeleton does not expand to accommodate growth, a caterpillar must shed it several times in a process known as molting. The caterpillar is the only life stage that molts. Once a butterfly emerges as an adult, it no longer grows. Depending on the species, molting generally occurs four to six times. Each stage between molts is called an instar, and the caterpillar at each instar is larger than the previous one. In the final molt the caterpillar transforms into a pupa, or chrysalis, the mummylike quiescent stage between larva and adult.

Molting is regarded as one of the most vulnerable processes a caterpillar goes through. In the period immediately before and after shedding its old skin, the caterpillar is immobile and can easily fall prey to a predator.

As with eggs, the length of time a butterfly spends as a caterpillar depends largely on whether it passes the winter in this stage (as many skippers do). If the caterpillar doesn’t overwinter, it will spend a few days to a week in each instar between molts, with development typically completed within three to eight weeks.

All butterflies form a chrysalis in which they transform from a caterpillar into an adult. The chrysalises of many butterflies hang from silk buttons called cremasters, as with the monarch chrysalises on the left, or are held upright by silken girdles, like the black swallowtail chrysalis on the right.

After a caterpillar has gone through four to six instars, it stops eating and searches for a safe place to pupate. During pupation, the caterpillar’s entire physiology undergoes drastic changes as its body restructures itself to eventually emerge as a winged adult. Chrysalis is the term for both this stage in development and the encasing at this stage, during which the structure of the insect is being completely reorganized. The term is derived from chrysós, Greek for “gold,” referring to the metallic-gold coloration of many chrysalises.

Pupa and chrysalis have the same meaning: the transformative stage between the larva and the adult. While pupa can refer to this naked stage in a butterfly or moth, chrysalis is used strictly for the butterfly pupa. A cocoon is the silk casing that a moth caterpillar spins around itself before it turns into a pupa.

The chrysalises of many butterflies hang from silk buttons called cremasters or are held upright by silken girdles. Some are disguised to blend into their surroundings, being generally green or brown and resembling leaves, stems, or wood. Others are covered in thornlike bumps. Some butterflies, such as swallowtails, overwinter as chrysalises. For butterflies completing development in a single season, the chrysalis stage lasts a couple of weeks.

Just before the butterfly’s emergence, the chrysalis usually changes color. You may also begin to see the markings of the wings through the now-translucent casing. It breaks open across the back and the butterfly crawls out from it. Once free of the chrysalis, the butterfly pumps fluid from its swollen body to its still-crumpled wings. The freshly emerged butterfly clings to the plant or structure next to its chrysalis to complete the process of metamorphosis, letting its wings dry and harden before taking flight in search of food and a mate.

This sequence of photos of a black swallowtail (Papilio polyxenes) shows how the chrysalis changes color just before the butterfly’s emergence and then splits open so the butterfly can crawl out. Once free from its chrysalis, the butterfly pumps fluid from its body into its still-crumpled wings.

It might appear counter to their beauty, but many butterflies feed at seemingly noxious sources such as mud puddles or animal scat. Here eight species of butterflies—eastern tailed-blue, northern pearly-eye, red admiral, silvery checkerspot, spicebush swallowtail, spring azure, cloudywing, and hoary edge—are feeding on one coyote scat.

The primary activities of adult butterflies are feeding, mating, and egg laying. Nearly all butterflies need to feed as adults. Nectar from flowers and sugar from tree sap, overripe fruit, or aphid honeydew provide most, but not all, of the nutrition that most butterfly and moth species need. To acquire additional nutrients, minerals, and salts, sometimes butterflies (males in particular) imbibe liquid from carcasses, animal waste, mud puddles, and moist soil. A few species of butterflies—such as tropical longwings, which can be found in the southern United States—eat pollen as well as nectar. Longwings collect pollen around their mouthparts and then combine it with their own saliva to break down the amino acids before ingesting it. This protein-rich meal enables them to live longer than most other butterflies and may even give them a reproductive advantage.

A male butterfly like this fiery skipper (Hylephila phyleus) may “court” the female by flying around her and rapidly beating his wings.

Male butterflies find females by sight or sometimes using chemicals called pheromones—natural perfume—at close range. The male may “court” the female by flying around her, and they may spiral up into the air together. This courtship is sometimes confused with a male warding off another male from its territory because both involve two butterflies flying around each other. If the female accepts the male, they couple end to end, with the tips of their abdomens joined. They may remain coupled for an hour or more, sometimes even overnight.

During mating, the male passes a packet of sperm and nutrients called a spermatophore to the female. The sperm then fertilizes each egg as it passes down the female’s egg-laying tube. After mating, female butterflies locate appropriate host plants by sight or scent and usually land on or near the plant to oviposit (lay eggs) singly or in clusters on or under the leaves. Some grass skippers do not land at all; they fly over their chosen host plant and drop the eggs one by one.

As humans, we need safe places to live, healthy food to eat, and protection from poisons. Butterflies are no different. To survive and complete their life cycle, butterflies need food plants for their caterpillars (which ecologists refer to as host plants or larval host plants), nectar to fuel their activities, safe places to take shelter, and protection from pesticides. Your garden can provide all a butterfly needs in a single space. Providing plants for caterpillars to eat, food for adults, and a secure place to pupate or overwinter can all be accomplished even in a relatively small yard. Later in the book you will find a directory of some of the best plants for supporting butterflies in garden settings; here we describe butterflies’ plant needs in general.

The best butterfly gardens provide both nectar and host plants and secure places for butterflies to pupate and overwinter.

Many species of wildflowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees are butterfly hosts. Caterpillars of some species will eat only a single species of plant or several very closely related plants, while other species will eat a wide range of plants from multiple families. Often, butterflies and moths have specialized relationships with native larval host plants. For example, research by Douglas Tallamy and his colleagues at the University of Delaware revealed that in the eastern United States, native plants support four times as many native butterfly and moth species as do introduced plants. This relationship between plants and butterflies is the result of a long history of coevolution.

Most butterflies lay their eggs directly on a host plant. This female silver-banded hairstreak (Chlorostrymon simaethis) is placing the egg carefully from the tip of her abdomen.

For the many butterflies that are host-plant specific, such as monarchs with their milkweed, the availability of these host plants is critical to their survival. These butterflies are limited to areas where their host plants thrive. For example, the federally endangered Fender’s blue butterfly (Icaricia icarioides fenderi) feeds almost exclusively on Kincaid’s lupine (Lupinus sulphureus subsp. kincaidii), which is itself threatened. Both species are found mainly in a narrow region of northwest Oregon, although the lupine enjoys a slightly larger range north into southern Washington and south into parts of central Oregon. As with all species that are highly selective with their food plants, the Fender’s blue will not survive without its host plant. At the opposite end of the spectrum is the gray hairstreak (Strymon melinus), a butterfly found from coast to coast in the United States. Its caterpillars feed on a huge variety of plants; more than eighty different plant species from at least two dozen plant families have been documented.

Most butterflies lay their eggs directly on host plants so that caterpillars after hatching do not have to travel far to begin feeding. When flying through a landscape—over gardens, across a meadow, around the edge of a woodlot—butterflies locate and identify host plants through a combination of sight and scent. From a distance, the females use both visual and chemical cues to guide them, picking up scent using their antennae. When a female butterfly lands on a potential larval host plant, she “tastes” it with chemoreceptors located at the tips of her legs to determine its suitability. (She can be choosy; a female seldom lays eggs on the first plant she visits.) A butterfly’s ability to find specific plants within the landscape is remarkable. Species of fritillary can locate violets that have senesced (dried) and are not visible. They lay eggs on or near these dried-up plants. The larvae hatch and immediately go into a period of suspended development (diapause), not feeding until the next spring when the plants are young and green.

Leaves are the primary source of caterpillar food, but these voracious animals also sometimes eat stems, flowers, and immature fruits. Although some butterfly larvae are generalists and feed on a variety of plant parts, others feed on just one or a few parts of their host plant.

This common buckeye (Junonia coenia), like most butterflies and moths, has a long tubular mouthpart called a proboscis that it unfurls and inserts into flowers to sip nectar.

Energy-rich nectar is the primary food source for most adult butterflies and moths, and is thus the major attractant to flowers. Butterflies can access either shallow or deep reservoirs of nectar, from a variety of flower shapes and sizes, with a long, tubular mouthpart called a proboscis. Nectar typically consists of fructose, glucose, and sucrose in varying proportions and also includes amino acids. Some nectar also includes secondary compounds such as lipids, antioxidants, and alkaloids. Both the volume of nectar produced and its sugar concentration vary widely across flowering plant species.

Many native plants such as Joe Pye weed provide plentiful nectar and will help attract butterflies to your garden.

Both native and nonnative plants attract butterflies with their nectar, but we believe native plants should always be your first choice. They often grow well because they are adapted to a particular area, and they are not likely to be invasive and crowd out other plants. Many native plants that provide high-quality nectar are also host plants for caterpillars. Such groups of plants include buckwheats (Eriogonum species), milkweeds (Asclepias species), thistles (Cirsium species), wild indigos (Baptisia species), and wild lilacs (Ceanothus species).

Butterflies are particularly vulnerable to predators during pupation, and safe places of refuge are critical. They also need places to overwinter, whether as eggs, caterpillars, chrysalises, or adults. And they need places to spend the night or to escape storms, especially as adults. The type of shelter varies depending upon the habitat in which the butterfly lives and the particular species of butterfly. Many species that live in prairies and meadows crawl down into the bases of grasses. Woodland butterflies may seek shelter under tree leaves, and alpine butterflies may take advantage of rock crevices. Most butterflies spend the night on their own, but some species, such as zebra longwings (Heliconius charithonia), can form large communal roosts in trees.

Caterpillars seek out many different places to pupate in gardens, including structures such as buildings and fences.

All butterflies must pupate. Caterpillars often pupate on or near their host plants. Chrysalises can be hidden away and hard to find—under duff or leaf litter, in a tree crevice, in tall grasses or bushes, or attached to a shrub, fence post, or building—but they have also been found in exposed places such as the strands of a barbed wire fence.

Many butterflies undergo a period of suspended development known as diapause, which enables them to survive stretches of inclement weather. During diapause, no growth or development occurs, and most feeding is also halted. Usually this happens during the cold winter months (overwintering or hibernation) or during the summer dry season (aestivation), when vegetation is no longer succulent or nectar-producing flowers are scarce. Strict summer aestivation is uncommon in North American butterflies and usually precedes an overwintering period (for example, a species goes into diapause during the summer dry period and remains in this state until the following spring).

Multiple periods of diapause can happen within one generation. This is the case for butterflies in many high-latitude or high-altitude locations that require two to three years to fully develop due to the short growing season and long winters. Living at elevations above 13,000 feet in the mountains of southern Colorado, the Uncompahgre fritillary (Boloria acrocnema) makes a good example. Eggs hatch in the summer and the caterpillars feed for a while before hibernating through the winter. In the second summer, they feed as caterpillars. Some may complete development, pupate, and emerge as adults; others will enter hibernation for a second time. When the third summer arrives, the overwintered caterpillars finish feeding, pupate, and finally emerge as adults.

Gardeners will not encounter this species but may still need to consider butterflies that go through a single period of prolonged diapause, up to a year or longer. The chrysalis of the anise swallowtail (Papilio zelicaon), a butterfly that is widespread in western North America, may remain in diapause through two winters and the seasons in between.

The majority of butterflies pass through diapause as a caterpillar or chrysalis, but some overwinter as eggs or adults. Species that go through diapause in the egg stage usually hatch in the spring and feed rapidly on tender new foliage. The adults that emerge then lay eggs that remain dormant from summer to the following spring. Groups of closely related butterflies often employ similar strategies when it comes to diapause, with some exceptions in each group. Many hairstreaks overwinter as eggs, while checkerspots often hibernate as partially grown larvae. White admirals and viceroys do the same but often wrap leaves around themselves and secure the leaves to twigs with silk to provide a secluded location. Duskywing skippers overwinter as fully developed caterpillars, pupating in the spring and emerging shortly thereafter.

Some butterflies like this mourning cloak (Nymphalis antiopa) overwinter as adults. They tuck themselves into tree cavities, logs, brush piles, old rock walls, and buildings for shelter against the winter.

Butterflies that overwinter as adults include anglewings, tortoiseshells, and the monarch butterfly. Anglewings and tortoiseshells tend to take shelter in both natural and manmade areas, including tree cavities, under logs or rocks, behind loose bark, within evergreen foliage, or tucked into stone walls, buildings, and fences. Most butterflies overwinter in or near the same place they were born. The most famous exception to this is the monarch, which may travel hundreds or thousands of miles each fall to overwintering sites along the California coast or in fir forests in Mexico. Other migrant species include cloudless sulphur (Phoebis sennae), painted lady (Vanessa cardui), and buckeye (Junonia coenia). Some migrant species do not make a return journey; individuals in the northern parts of their range die with the arrival of winter. While some of these species are known to lay eggs throughout their journey, these northern regions are often repopulated by new migrants the following year.

No matter which family they belong to, butterflies need larval host plants, nectar plants, and sheltering habitat to support the various stages of their life cycle. We turn next to how to design a garden that will meet their needs.

Depending on the species and the location, butterflies may use a variety of features in the garden for shelter.

Monarchs are not the only butterflies that migrate. Other migrants include the cloudless sulphur (Phoebis sennae).

In addition to a diversity of nectar and host plant species, butterfly gardens should strive to offer a range of vegetative structure, including plants of varying heights and stem densities.