Not all butterflies occupying your garden are obvious. Fallen oak leaves provide a camouflaged perch for low-profile butterflies such as the common roadside skipper (Amblyscirtes vialis).

Once you start gardening for butterflies you will begin noticing them—and a variety of other flower visitors like bees and hummingbirds—all around your garden. You may already be familiar with the thrill of finding an unexpected winged visitor gathering nectar from your daisy or a fantastically striped caterpillar quietly munching away on some willow leaves. To watch butterflies is to become intimately familiar with their habits and needs, which ultimately leads to a greater understanding of how your garden can provide for them. Before you know it, this familiarity will be influencing everything you do in the garden, from changing your mowing and fall cleaning regimens to planting specific host and nectar plants to entice certain butterflies to become frequent visitors or permanent residents.

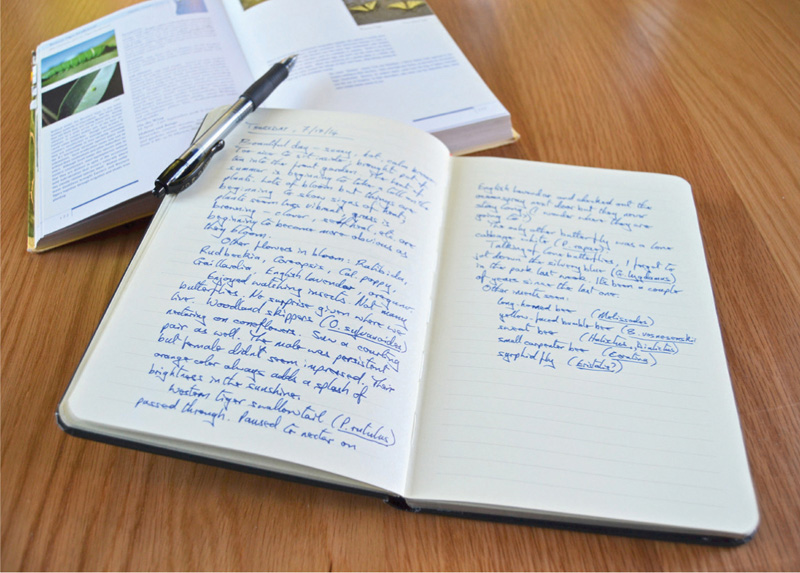

As you watch your butterflies and learn more about them, you may want to start recording their appearances and noting your observations. This may take the form of photographs or sketches, which can be shared with other enthusiasts. You may even start to build a list of local species. These observations can propel you to become involved in citizen science projects where you can collect data to inform large-scale science and conservation projects. Eventually you may find that your butterfly watching even leads to becoming a local expert, organizing classes or giving talks at the local library or schools. It may take you out into the natural world at large, where you can look for butterflies in all of their varied habitats.

This chapter provides tips for finding and observing butterflies. We also briefly explain how you can rear your own adults from larvae collected in the field.

Not all butterflies occupying your garden are obvious. Fallen oak leaves provide a camouflaged perch for low-profile butterflies such as the common roadside skipper (Amblyscirtes vialis).

The first step in becoming a butterfly watcher is figuring out where to look for them. The best search technique depends on the life stage you are seeking. Adult butterflies with their colorful, graceful flights through the landscape are easy to notice, particularly if they are large and showy like admirals, swallowtails, and monarchs. The smaller butterflies are more often overlooked in the garden, even though they are no less beautiful. Grass skippers keep a low profile, flitting near the ground and blending in with grasses and forbs with their tawny brown or tan bodies. Blues, coppers, and hairstreaks can be the size of your thumbnail and display iridescent blues, bright orange chevrons, chunky black spots, and delicate tails. Once you know where to look in your garden, you may be surprised how many of these small animals have been flying under your nose the whole time.

The best time to search for adult butterflies is between the hours of ten in the morning and four in the afternoon because this is the warmest part of the day, and they are most active when the sun is shining and temperatures are above 60 degrees F. It doesn’t hurt to have a calm day, either, especially if you’re hoping to take photographs. Keep in mind that in midsummer many butterflies seek shelter in the middle of the day as temperatures peak and then become active again later in the afternoon. This is especially true in southern regions.

When approaching a butterfly to identify it, move with smooth, fluid steps so that you do not startle it into flight. Also be sure to keep your shadow from falling across the butterfly as you approach. Sometimes seemingly inconsequential things can have an effect on your observations. For example, even clothing can make a difference: a brightly colored shirt combined with a quick movement can surprise a butterfly into flight, whereas the same movement might not cause alarm when cloaked in plain colors. On the other hand, bright colors attract males of certain species, so you may get a few inquisitive darts until they determine you are not an intruder or a potential mate.

Immature stages of butterflies can be equally rewarding but trickier to find. If you are hoping to find eggs, larvae, or even pupae you will need to carefully search known host plants, turning over leaves and stems, and check nearby structures and safe places where caterpillars may have crawled to pupate. When you search for these stages, knowledge of specific host plants and what time of year you are likely to see each species is particularly important and can help you home in on the right spots to look.

Another way to find eggs is to closely watch for an ovipositing female laying eggs on host plants. When she flies away, step in and carefully look for the tiny egg, often on the undersides of leaves or along stems. Identify the plant and check to see if it is a known host plant for a specific species, and then see if you can corroborate that with your sighting of the female. The host plant is a good way to narrow down species identification when no adult is in sight and only an egg or a larva is found. When you are searching for caterpillars, look for frass and signs of chewing.

A young Gulf fritillary caterpillar leaves clues to its location in the form of frass and chewed leaves. Use these clues to home in on caterpillars, which are often hidden on the undersides of leaves.

Learning to search for and find immature stages of butterflies is an entirely different way of butterfly watching and will enable you to learn quite a bit about each species’ life history and special requirements. It is also a great way to continue your observations when conditions are not ideal for adults.

Butterfly watching is quickly becoming a popular pastime, rivaling the popularity of bird watching. Tools for butterfly watching are simple: a good regional field guide, a notebook and a pen, a pair of binoculars, and perhaps a camera. When choosing binoculars, be sure to select a model that allows for close focusing (a minimum of 6 feet or less). A small plant press may be useful for collecting plant specimens to be identified later. Other potential equipment includes nets, jars, and maps. Look for regional butterfly checklists online and in print (see “Additional Resources” and “Suggested Reading”) to get an idea of which species exist in your area and whether they are rare or common.

Practice and simple equipment such as a net and a viewing jar allow up-close viewing of butterflies.

Some butterfly enthusiasts observe butterflies strictly with their eyes and binoculars, while others prefer to use a net to temporarily capture butterflies for closer inspection and identification. If you use a net, realize that you are handling a living thing. People have been netting butterflies for hundreds of years, and you can safely net and release butterflies without injuring them. Correct net technique involves not just catching the butterfly but also handling it properly after you catch it. You can remove the butterfly from the net by gently grasping its wings with your forefinger and thumb and removing it from the net, or by using spatulate forceps, similar to those used by stamp collectors. Forceps that are serrated or more pointed may inadvertently tear a butterfly’s wings. You can also use a jar or buy a container with a magnifying glass in the top to look at the butterfly. If you use a jar, make sure it is large enough for the butterfly and always look at the butterfly in the shade. The inside of the jar can get hot quickly in the sun and the butterfly will become more active, which makes it hard to see details.

The vast majority of what we know about butterflies has come from extensive notes, letters, and records written by amateur butterfly enthusiasts. The importance of writing down your observations cannot be overstated. Each piece of information you keep gains significance as time goes on and may one day be used by researchers.

As you get to know the species in your garden and afield, consider keeping a small notebook of your observations. At a minimum, keep track of the species (including number of individuals observed), its behavior, associated habitat and/or host or nectar plants, time of day (preferably in military time), date (formatted day/month/year, with month spelled out), weather (temperature, cloud cover, wind speed, unusual weather events before or during your observation), and specific location. Be sure to include your name as the observer.

Behavioral notes can be especially important in studies of poorly understood species. The location is also very important, as an observation without this information means little. Many records from the past are accompanied by vague location information such as “Dallas, TX” or “the Appalachians,” information that is not very helpful to someone trying to relocate a population. These days, with Internet resources, smartphones, and an abundance of maps, locations can be specified much more precisely. Perhaps the best way to record a sighting is to use latitude and longitude. Numerous smartphone apps are now available that can pinpoint your latitude and longitude. Additional locality information such as directions, place names, street names, and names of water bodies is also helpful. This could be something as simple as your address if the butterfly was sighted in your home garden.

It is best to write down your notes and observations immediately, as letting even a short period of time elapse between sighting and notes can alter your memory and blur important details. As you keep these records and observations, think about starting your own “life list” or county list, a practice adopted from birders that many butterfly watchers enjoy using.

Keeping detailed notes about your observations is a great way to start learning about the various butterfly species visiting your garden.

Collecting has been vital to our understanding of butterflies and has led to great steps forward in knowledge of species’ life history and distributions—as well as to some of our most ardent butterfly conservationists. It has helped scientists, naturalists, and land managers understand these animals, identify species, and document biodiversity. Collecting can also be an extremely helpful source of information for setting conservation priorities, monitoring climate change, and educating others. Much important research rests firmly on responsibly gathered, well-curated collections made by amateurs and professionals alike.

If you are going to collect, you need the proper equipment and the know-how to ensure that you do it responsibly. Collecting of butterflies should always be done with consideration of its possible consequences. Collecting will not impair most butterfly populations, but intensive collecting can potentially harm very rare and ecologically vulnerable species. Instances of this are uncommon but can happen, especially through aggressive and heedless commercial collecting.

Xerces recommends the following practices for collectors, whether scientists, amateur enthusiasts, or children making a study collection:

• Have specific objectives for your activity rather than just killing insects randomly.

• Collect no more individuals than are needed, particularly of females, even in cases where a series of specimens must be secured for studies in variation and evolutionary biology.

• Always follow the law. Do not collect from areas such as national parks or state parks where collecting is prohibited without a permit. Never collect specimens of a species protected by federal or state laws, local ordinance, or any relevant international treaty. Use common sense.

• Do not collect specimens of a single species in large numbers year after year from the same locality in the same season. If regular sampling is necessary, be conservative and take more males than females, whose removal makes much more difference to the population.

• Honor each specimen collected by recording the precise location and date of collecting along with the name of the collector on the envelope or pin label. If these facts are not noted, nothing can be learned and a potentially valuable scientific specimen becomes a mere curio—just a dead insect on a pin.

• Do as little damage as possible to the habitat in collecting (and watching) locales.

Taking photographs is an effective alternative to collecting for many purposes. With high-quality digital cameras and smartphones, you can often get diagnostic photos for identification. Binoculars can be a great help in observing species that are otherwise difficult to reach or when you want to see intimate details of a butterfly’s life. You might also consider making a collection from road-killed butterflies. The son of one of the authors has a nice educational collection assembled from already-dead specimens, and one Xerces member collected every species of butterfly known in New Jersey in this manner.

Photography is an excellent way to observe butterflies in your garden and capture them in their natural settings. While they can be difficult to photograph because they startle easily and are often busily moving from flower to flower in search of nectar, and while it takes some patience, photographing butterflies can be a great pleasure. Photography will allow you to closely observe their behaviors and to document and identify species without handling them. Photographs are also an excellent aid to identification once you have left the field or garden. Just be sure to capture multiple perspectives of each butterfly you see, as minute details are not always easily visible in photos, and diagnostic features may be on both the undersides and upper sides of the wings.

Numerous online communities exist to help with identification or let you track all of your sightings. For example, both e-Butterfly.org and the Butterflies and Moths of North America website allow users to upload photographs of species, which are then pinned to a map of nationwide observations. Each upload is vetted by a regional expert, adding to a large and quickly growing collection of citizen-gathered data. A similar resource, the Butterflies I’ve Seen portal through the North American Butterfly Association website, allows users to upload photos and observations, categorized by field trips, to a greater database, in addition to creating their own life lists of butterflies.

An easy way to photograph butterflies is to set up your camera near flowers that attract adults. Tripods or monopods are especially useful for this method, as they allow for clear shots without camera shake. If using a tripod, consider leaving the head partially untightened so you can easily swivel the camera around to keep your target in focus. If you want to follow a subject around, be slow and quiet, and do not let your shadow fall across the butterfly as you approach. You may want to gradually move forward on your knees, focusing and snapping a few shots along the way in case the butterfly spooks and flies away. Butterflies need to heat up in order to fly, so early morning hours when butterflies are still cool and potentially even damp with dew are the best time to search for and photograph them.

Photographing butterflies takes a bit of patience but can be a very rewarding way to document the species in your garden and local area.

A digital single lens reflex (DSLR) camera with interchangeable lenses is ideal for photographing butterflies, although digital compact cameras have increasingly sophisticated zoom lenses and produce good quality images. Many other cameras, including simple point-and-shoot and smartphone cameras, will also work for the beginner. The standard for butterfly photography is a macro zoom lens, which will allow you to take fairly close photographs without needing to get so near your subject that you startle it away. Many photographers prefer lenses with a range of 70 to 180 mm. Handheld flashes and diffusers may be helpful in achieving crisp shots with good lighting, but natural light (especially in the golden morning and evening hours) can also work very well. A flash can help fill in details on the wings and will also eliminate some movement (blurring), but if you do use a flash, try to place it in the same position as the sun in order to make shadows look more natural.

There are many other aspects of photography to consider, including the size of the aperture, the depth of field, and the shutter speed (using a faster shutter may help you get a clear shot if your butterfly is on the move). Most cameras these days feature a range of automatic settings from high-speed sports to portrait, with a close-up setting (typically marked with a flower icon) for shooting at shorter distances. As you become more comfortable with photography, you may want to move on from these automatic settings. In the meantime, program mode is a good place to start, letting the camera select shutter speed and aperture while you concentrate on the butterflies.

Regardless of your camera type, the best way to improve your butterfly photography is to practice. Get to know your particular camera and its settings and practice with not just butterflies but other animals and stationary subjects as well. Numerous books are dedicated to butterfly, insect, and nature photography, all of which offer great tips on techniques and the latest equipment.

Raising butterflies can be a way to observe all of the life stages and to help kids understand metamorphosis. Children and adults alike can be filled with wonder at the sight of a tiny caterpillar growing, pupating, and then emerging as an adult. This takes planning, equipment, and time, but many resources are available to help those who are interested.

Not all butterflies are good candidates for rearing. Some have specific life cycle strategies such as association with ants and do not do well in captivity. It is best to pick a well-known species such as monarch (Danaus plexippus), painted lady (Vanessa cardui), or cabbage white (Pieris rapae). Eggs can be harder to find than caterpillars and harder to rear.

To rear a caterpillar, you first need to find one in your garden. Follow the tips earlier in the chapter on finding and observing butterflies to locate a suitable caterpillar. Try to find a feeding caterpillar so that you know which host plant it is eating; if you find a caterpillar away from its host plant, it is best to leave it alone. Monarchs are a good choice as they eat only milkweed. Cabbage whites are another good choice as you can often find them on the cabbage or broccoli growing in your yard. The host plant should be easy to access and harvest; you will need fresh leaves every day. Caterpillars eat many times their weight in plant materials, so you will need an ample supply of the host plant to raise a caterpillar.

Be sure to collect some of the host plant when you collect the caterpillar. Place your cuttings in a moist bag and your caterpillar in a dry collection container with some of its host plant. When you get inside, put your plant cuttings stems down in their own jar or vase with a small amount of water in the bottom to keep them fresh, and then place your caterpillar on the leaves of the plant. You may want to cover the mouth of the jar or vase to keep your caterpillar from accidentally falling into the water. Then place the plant and the caterpillar in an enclosure so the caterpillar cannot escape.

Eggs can be hidden on the undersides of leaves or along stems. This tiny egg has already been vacated by its Fender’s blue inhabitant; note the tiny exit hole that gives the egg a donutlike shape.

Caterpillars can be kept in an aquarium, a large jar, a bug cage, or another container. You will need to clean it every day, so the container should be easy to open. It should have a screen covering or holes for air flow and should allow you to see the caterpillar inside. Make sure the air exchange is ample by either using a mesh cover or poking holes in the container lid. Unless you plan to move the chrysalis, the cage should be large enough for the adult to expand its wings when it emerges.

Caterpillars are voracious eaters and can quickly decimate your host plant supply. Be sure to give them plenty of fresh food and the space they need to complete their life cycles.

Keep the caterpillar’s new home out of direct sun and be sure to replace any wilted leaves with fresh ones from the appropriate host plant. It is critical you provide the correct host plant, as many caterpillars will eat from only one plant or plant family. Be sure to clean out the container frequently—your caterpillar is an eating machine and will produce a lot of droppings. Add some twigs and small branches to the container so the caterpillar has something other than the container lid to attach to when it pupates.

The life cycles of butterflies vary, but caterpillars will usually eat for seven days to more than two weeks before they pupate. The chrysalis may last for a similar period of time before the butterfly emerges. Always release the butterfly where you found it. This helps ensure it will have the necessary resources to complete its life cycle, and it means you are not releasing a butterfly into an area where that species may not have been found before.

Recently, citizen science programs around the world have harnessed the enthusiasm of volunteers to collect and contribute scientific data. Citizen science is a way for the public to engage in important scientific discovery and allows for outdoor classrooms that can inspire young and old alike. The first naturalists and scientists were almost all self-taught, not being trained at universities, but as science shifted from our backyards to university labs it became harder for people to engage in scientific activities. Now with the advent of technology like smartphones and because of advances in identifying species, everyone can help scientists better understand the natural world so we can better conserve it.

Smartphones are enabling a new generation of citizen scientists to collect and submit photographs and other observations in real time.

The power of citizen science is the ability to collect huge data sets across large geographic areas, which is often impossible for the single researcher or research team. People from all walks of life now participate in projects that run the gamut from analyzing the extent of sea star wasting diseases to understanding rangewide shifts, migrations, and population declines of dragonflies. Local bioblitzes (rapid inventories of all plants or animals that generally take place over a twenty-four-hour period) are often hosted by parks and schools in an attempt to identify all species in a given area. These blitzes rely on volunteers to help find, photograph, and collect specimens that are identified or verified by regional experts, and they are a great way to become familiar with your local species and get to know other enthusiasts in your area.

This tagged monarch is ready for its migration to Mexico. Tag recoveries at overwintering sites give scientists a better understanding of migration pathways throughout North America.

Numerous citizen science programs focus on butterflies. Great Britain has the longest-running butterfly citizen science programs, and the United States boasts a growing number of projects and participants, particularly relating to monarch butterflies. Many of these projects depend on volunteers to count monarchs at overwintering sites, monitor larval populations and monarch health, track migrations, tally species at annual events, and upload photos and location information to get a sense of global distributions over time.

BAMONA strives to bring verified lepidopteran occurrence data and natural history information together in a single publicly accessible database. Citizen scientists can contribute observations and photographs to be included in the database, and knowledgeable individuals can apply to become regional monitors.

eButterfly is an international citizen science project dedicated to butterfly biodiversity, conservation, and education. Researchers associated with the website use citizen-contributed observations to study how global climate change is affecting our natural environments and how we can make decisions to help mitigate the effects on butterfly biodiversity and abundance.

Journey North is a global study of wildlife migration, including monarch butterflies. This organization provides information on tagging and monitoring monarch butterflies as they migrate in the eastern United States.

The MLMP is a project of the University of Minnesota’s Monarch Lab. Volunteers in the United States and Canada collect long-term data on larval monarch populations and milkweed habitat in order to better understand how and why monarch populations vary in time and space.

monarchmonitoringproject.com/index.html

The Monarch Monitoring Project conducted by New Jersey Audubon’s Cape May Bird Observatory seeks to better understand the fall migration of monarchs along the Atlantic coast. Volunteers assist by tagging thousands of monarchs every year, some of which are rediscovered at the Mexican overwintering grounds later in the year.

Based at the University of Kansas, Monarch Watch is a nonprofit education, conservation, and research program that focuses on the monarch butterfly, its habitat, and its spectacular fall migration. Monarch Watch has a broad network of volunteers who tag migrating monarchs and report tag sightings.

National Moth Week is held during the last full week of July to celebrate the beauty, life cycles, and habitats of moths. “Moth-ers” of all ages and abilities are encouraged to learn about, observe, and document moths in their backyards, parks, and neighborhoods. Moth information gathered at NMW events can be submitted via the website.

Regional NABA chapters host butterfly counts each year, most often around the Fourth of July but also in the spring and fall. New members are welcome to join counts as well as other field trips to monitor butterfly populations and report sightings.

Project MonarchHealth seeks to understand host-parasite interactions by tracking the spread of a protozoan parasite (Ophryocystis elektroscirrha) in wild monarch populations across North America. Citizen scientists collect parasite spores from captured-and-released monarchs and send them in to the MonarchHealth lab for testing.

Citizens help researchers at Iowa State University to monitor red admirals and painted ladies by providing observations of territorial behavior, migration, life history, number of broods, and seasonal variations. Includes the Vanessa Migration Project.

The Southwest Monarch Study studies the migration patterns of monarch butterflies in Arizona. Their activities include tagging monarchs, monitoring milkweed populations, and searching for habitats that attract and support monarchs. People of all ages are welcome to participate. The Southwest Monarch Study also provides educational programs to raise monarch awareness.

The Western Monarch Count is an annual effort of volunteer monitors to collect data on the status of monarch populations overwintering along the California coast. Thanks to the extraordinary efforts of a cadre of volunteers, more than a decade of data demonstrates that monarchs have undergone a dramatic decline in the western United States.