![]()

The following week I go again to the pub on Landsberger Straße to hunt through Der Stürmer and find several more corresponding names. Disturbing. But maybe Raffi accepted money from Nazis only so he could undermine their work. He wouldn’t be capable of doing anything terrible, and I could never believe he was involved in a murder.

I glimpse Vera, Rolf, and Heidi only once more that year, on the evening of the 19th of April, though I spot Mr Zarco coming and going with some regularity, of course. I’m making Hansi pose as a reader at the kitchen table—his hands under his chin and eyes gazing purposefully down at my copy of The Magic Mountain—when a harsh and familiar voice coming from outside makes me bolt upright. I rush to the window and find Vera in the courtyard, her hands on her hips, irritated about something. Heidi and Rolf come through the door to the front building a few moments later. He’s chomping on a cigar and Heidi, blue lace at the collar of a pretty white dress, is carrying a pink cake box. Vera calls them forward, her hands in a frenzied whirl, and Rolf gives Heidi a peck on the cheek as if to say, Bear with her …

My first urge is to call out. My second is to lean back out of sight, which is what I do. Our window is open, so I can hear them clearly.

“Stop that!” Vera snaps at her friends. “It’s enough that you two walk like tree stumps, you don’t have to compound the problem with unnecessary affection.”

“Define unnecessary,” Rolf replies, laughing.

“All affection between married couples. It’s an affront to all we hold dear in Germany.”

“Vera, you make my bones ache!” he tells her, but Heidi, gently, suggests that Vera go on up the stairs and they will catch up.

Impatient with everyone and everything. The modus operandi of a goddess who spent years on view to gaping circus-goers.

Heidi and Rolf penguin-walk behind her into the rear building.

“What is it?” Hansi asks, still posing perfectly. An amazing child. He deserves a medal from the Artists Guild.

“And that’s that,” I whisper with resentful finality, sensing I’ll never get to know such special people. I sit back down and grab my pencil.

“That’s what?” my brother asks.

I aim the pencil point at him threateningly. If he were normal, this is where he’d scream at me to stop being such a bully or call my mother for help. But Hansi is who he is; he simply rests his head on the table and vanishes into his cloud of thoughts.

Papa enters the kitchen a short time later and, sensing something is wrong, says, “Show me your drawing, Häschen.”

A kind man, but sweetness in parents can be irritating—like too soft a pillow. I stifle my urge to scream and hand him my sketchbook. Papa studies my previous drawing—Hansi in profile, his tongue poking between his lips and eyes focused on a distant surprise. “No doubt about it—you’ve got talent,” he says proudly.

“It’s all wrong,” I say, because some dark part of me wants to spoil our easy intimacy.

“It’s not—I’d know that handsome boy anywhere.” He rests a gentle hand atop Hansi’s head, as he does when he knows his son is lost to us. We both do that a lot. Returning my sketchbook to me, Papa says, “You’re more of an artist than you know.”

“Thanks,” I reply, and it is a lovely thing to say, but I’m really thinking, Why are my family and Tonio not enough for me?

Vera, Heidi, and Rolf must have been invited to Mr Zarco’s for Passover dinner. If I’d kept the curtains open, I’d probably have spotted K-H and Marianne, too.

That night before bed, Papa discovers that an envelope with my name on it has been pushed under the door. Alone in the room I share with Hansi, I rip it open and find a photo of a woman’s swollen belly—as smooth and bright as marble in the moonlight—and a neatly printed note: “Our child and me—first portrait. World premiere four months away! Love, Marianne and K-H.”

Raffi comes home in mid-May, his skin as dark as cinnamon and his black hair falling down to his shoulders, the picture of a Biblical acolyte. We talk in our courtyard, and I try to be interested in his descriptions of Egyptian life 3,300 years ago, but the Nazi names we don’t mention lie like cadavers between us. A week later, unable to bear the chill I feel whenever I pass his apartment, I knock on his door one evening after supper. His parents are out, and he and I sit in his room, me on his neatly made bed, him at his desk chair, which he has turned around so he can lean forward over the cane-work back.

“I can’t tell you much because other people would be in danger,” he says even before I have a chance to explain why I’ve come. “But what I told you was the truth—it was a shopping list.”

“Have you been getting money from the Nazis on your list to support your fieldwork?”

He laughs in a single burst. “That’s a good one!”

“Then why the British money? Didn’t you intend to use it in Egypt?”

“Soph, you’ve got far too vivid an imagination for your own good.” In a low voice, he tells me, “I was bribing Nazi politicians. And others with similar ideas. They prefer British pounds because it’s a more solid currency than the mark. Every time I made a bribe, I wrote down a name and a date.”

So I was partially right. “Bribing them why?” I question.

“To get their support on certain issues. To ease up on their hateful rhetoric.”

For the first time in weeks, I feel as if the ground is solid beneath me. “And where did you get the money?”

“Isaac told me you know now about The Ring. The members pay dues according to how much they can afford. I used some of our … our funds to purchase pounds on the black market.”

Relief sweeps through me. “Thank God. I thought …” I shake my head at my silliness.

“You thought I’d switched teams, didn’t you?” Only now realizing that I probably copied down his list, he jumps up. “You took down my hieroglyphics and … and then had them translated somehow,” he says, horrified.

“Yes, Dr Gross, at the …”

“So Dr Gross knows what you found out?”

“No, I never mentioned your name. And he has no idea what links all the names on the list. Or what the numbers mean. He thinks they’re part of a game.” I explain what I told Dr Gross.

“We can’t be sure he’s forgotten what he saw.”

Raffi looks off into his thoughts. I see fear in the clenching of his jaw.

“I did something really dumb, didn’t I?” I observe.

He smiles generously. “No, it’s going to be all right. Don’t worry.”

“I’m sorry, but I was really worried about you.”

“Forget about it.” He sits with me and tells me to turn so he can braid my hair—a vestige of his babysitting duties.

I can see from his face that he’s pondering how to rectify the situation. “Raffi, I’m sorry,” I say.

“Everything is okay. In any case, I’m out of the bribery business. So none of this matters anymore.”

“Can you tell me who was chasing you that day Tonio and I helped you?”

“Soph, I can’t make braids if you keep turning around! It was someone who wanted to learn who I’d been bribing.”

I love the pull and tug of his hands. “But what if the police interrogate you? Or Nazi thugs?”

“All I could tell them would be old news at this point,” he assures me, his voice now secure. “The only people who could get in trouble besides me would be the Nazis themselves. Because I would never reveal the names of the people in The Ring.”

Bravado or the truth?

“Did Georg Hirsch plan the bribery campaign? I mean, he was head of The Ring, wasn’t he? Was that why he was killed?”

Raffi leans past my shoulder and looks at me darkly. “I told you these were serious, adult matters.”

“Does Mr Zarco know why Georg was killed?”

He grips both my shoulders and says threateningly, “Soph, either you shush or we won’t be able to be friends anymore.”

Georg was killed by a Nazi assassin because he threatened to go public with the names of National Socialists being bribed by The Ring. After all, accepting hush money from a group filled with Jews would discredit them completely—and look very bad for the party in general. That’s what I soon conclude, but I don’t share my thoughts with anyone, not even Rini. I tell her that Raffi’s list consisted of the names of Nazis about whom he’d written letters to the Chancellor, denouncing their anti-Semitic beliefs. She’s disappointed, since it’s hardly a discovery worthy of the sleuthing we’ve done, but it’s safer for Raffi this way. And maybe for Rini, too.

Over that spring and summer, Mr Zarco and I are friendly whenever we bump into each other, but I can tell from the deliberateness in his speech and hand gestures that he’s waiting for me to make the first move to renew our friendship. “Reserved” is how Mama describes him. “Secretly exuberant” seems more accurate, though Papa says that makes no sense. He has the appreciation for poetry of a shoehorn.

Rini suggests that the stunning Nazi victory in the July elections may be responsible for Mr Zarco’s reticence. After all, I’m a Christian and he’s a Jew, and Hitler now presides over what has become the most powerful party in Germany, with 230 seats in the Reichstag. And it’s a fact that everyone I know is more tense than usual. Even Papa, who explodes at me for my faulty dishwashing one warm August evening, sending me to my room in tears. Mama, sitting at the foot of my bed, confides that the election results have left him plagued by insomnia. So maybe sleeplessness is a curse I inherited from him.

Seeing Hitler’s speeches in newsreels, we grow familiar with his spasmodic, epileptic rants, as well as his Viennese suburban accent and vocabulary.

“The personality of a village rat-catcher,” Papa tells me. “Mark my words, he’ll be sent back to his garret in Bavaria in less than a year.”

Like most Berliners, Papa pronounces Bayern, Bavaria, as if it’s a land of toothless troglodytes. That must hurt Mama, who loves her homeland as if it’s a magic kingdom in a fairy tale, but I’m too young—and maybe too resentful of her—to direct any words of sympathy her way.

Papa’s opinion of Hitler is the popular consensus, but my art teacher, Frau Mittelmann, disagrees. She’s the person who first interested me in sketching. No one can draw a daisy, carob pod, or stuffed walrus head like her, except maybe Albrecht Dürer, whose work she always shows us as inspiration. Frau Mittelmann has the pointy face of a fox, with a range of smiles from devilish to beatific that would be the envy of any actress, and she always darts around class as though she has just drunk an entire pot of coffee. She has short brown hair that she combs straight back like a man—very stylish, and she wears antique clothing in bright colors, like one of the Gypsy dancers I once saw on the KuDamm. To begin a drawing session, she always reads a quote from a famous painter. The one that makes me tingle is from Cézanne: “Fruits like having their portrait painted. They seem to sit and ask your forgiveness for fading. Their thoughts are given off with their perfumes. They come with all their scents, they speak of the fields they have left behind, the rain which has nourished them, the daybreaks they have seen.”

When I mention Papa’s opinion of Hitler before class one day, Frau Mittelmann smooths down the front of her floral-print smock with tense hands. “Your father should never forget that the Pied Piper was a rat-catcher, too,” she says menacingly. A few minutes later, while we’re sketching two proud yellow apples and the sadly withered pomegranate that doubles as her paperweight, she kneels down beside my desk. “Hitler has vowed to free us from our shame over our defeat in the Great War,” she whispers. “But we’ll have to give him our children in exchange.” Then she stands up, her knobby knees creaking, and says with uncharacteristic coarseness, “I must be mad to discuss these things with you. Get back to your drawing, Sophie.”

Is she afraid that I will report her to Dr Hildebrandt, the school principal? We’ve all heard the rumors that he attended a Nazi rally in Nuremberg last year.

Over lunch that day, I complain about Frau Mittelmann’s brusqueness to Rini.

“You just don’t understand, Soficka,” she tells me. “You can’t imagine the pressure we Jews are under.”

Rini often calls me Soficka, the cka suffix borrowed from my horrid middle name, Ludowicka.

“So explain it to me,” I say, digging my fork into my boiled potatoes.

“That would be pointless.” She lands with all her certainty on her last word, and I feel the thud deep in my chest. “You are either a Jew or you aren’t, and all the goodwill in the world can’t change that.”

She sounds as if she’s glad that a Semitic wall has grown up between us, which makes me so mad I could clock her right over the head with my history book, but Rini is in one of her squinty-eyed black moods, so I ask her instead why she thinks Hitler has had such success of late.

“Once you pass the outskirts of Berlin, my dear, you are back in the Middle Ages as far as the Jews are concerned,” she tells me, saying my dear in English because it’s her latest affectation. “Three steps past Neuenhagen Süd, our country becomes an anti-Semitic wasteland. The people out there”—Rini tosses away a dismissive wave in the general direction of Silesia—“still think we have tails and horns, and that we boil Christian children like you and Hansi in cauldrons for our Passover dinner.”

“I don’t think I’ve enough meat on me even as an appetizer,” I say, making Rini laugh, “and Hansi would taste really bland, like over-boiled rice.”

Our German teacher, Dr Fabig, gathers Rini, me, and a handful of other students around him a few days later, having overheard our political conversations. He speaks in a hushed voice while stuffing papers in his briefcase—dark leather, with a brass handle—then stands it on his desk. He takes off his wire-rim glasses, which he does only when he’s upset. “The Volk despise our great writers. They think Goethe is far too effeminate. And Schiller, my God”—here, Dr Fabig shakes his head morosely—“my poor dear Schiller puts them in a catatonic state. And now that the Jews are considered un-German, I’m afraid Heine is done for.” He stands up and grabs the handle of his briefcase, making ready to go. “As for Rilke, they could never take the time away from counting their spare change or milking their cows to understand what he writes. They cheer for Hitler because he despises our great men. He prefers reading a weapons catalogue to Novalis. It’s as simple as that.”

Frau Koslowski, from the neighborhood grocery store, says that posters of Hitler and the Nazi Party are everywhere because we have no icons in our churches. The way her milky eyes focus on me, as if I’m to blame, makes me take a step back. “If you Germans had saints around you, listening to your every heartbeat, then you would not need a leader to speak to you of the glories of this world.”

Raffi tells me in a scornful voice, “A gangster is what the rabble want—a man who will barge into the homes of his enemies with both hands swinging and a grenade in his pocket, and send all the crystal crashing to the ground, then blow up the evidence behind him.”

Even Hansi has an opinion about Hitler, which he mostly expresses by covering his ears every time our Chancellor rants on the radio. “He shouts too much!” my brother observes.

So it is that we begin referring to Hitler as the little man who shouts.

“He’s the only politician with vision,” Tonio’s father, Dr Hessel, tells me.

I’m in his sitting room, waiting for Tonio to dress, studying the framed picture of the Nazi leader that’s joined the photograph of Czar Peter on the wall behind the couch. Hitler is giving his stiff-armed salute to a cheering crowd.

“He sees what we could become if we aspire to greatness—to heaven on earth,” Dr Hessel continues, speaking to an audience that isn’t there, like a man who has confused Wagner’s operas for real life.

Tonio himself is convinced you have to shut your eyes to understand the man’s charisma. “Sophie, I admit that Hitler is physically repulsive,” he says, “so don’t look at him. Then you’ll hear that his passion is real—more real than anything you’ve ever heard before.”

I close my eyes tight while we’re watching a newsreel of a rally in Munich, but all I can hear is his painful, frantic urgency and provincial pronunciation. A passionate rat-catcher that could only ever appeal to the willfully blind. That’s what I think.

And who would lose to Tarzan in any battle of wits, I add to my description a few minutes after the newsreel ends, because Tonio has dragged me to see Tarzan the Ape Man, and as soon as we’re transported to that wondrous black-and-white Hollywood jungle it becomes clear to me—and likely every woman and girl in the Ufa-Palast Theater—that a bare-chested Johnny Weissmuller is someone we’d prefer to vote for. But Tonio and I have kissed in that inhabited darkness—floating between the screen and our seats, between California and Berlin—and I don’t want to upset him. Though it turns out he has an answer all ready for me …

“Weismuller is an Aryan name,” he says as we step outside in the warm summer evening, “which just proves what Hitler has been saying about the superiority of our race.”

Our race? Doesn’t one of us have a Slavic mother?

Uncharacteristically, Mama swears she has the definitive answer to all my questions about Hitler: he owes his success to too few calories in German bellies. “Five million people practically starving, and twenty million more who are afraid to join them, are going to make the wrong decision every time. Hunger goes to the brain.”

The certainty in her voice … It occurs to me then that she must have gone without food as a girl. Tender feelings well up inside me. “Did you and your sisters often go hungry?” I ask.

“Of course not,” she tells me, and her deadly frown makes me feel foolish for caring about the girl she once was.

While chopping leeks for the potato soup, I gaze down to hide my speculations about what wrong decisions Mama made because of her own hunger. My fear—so bottomless it leaves me in a cold sweat—is that giving birth to a certain badly behaved girl was one of them. Maybe my name is right at the top of her list of errors.

I remember what Mr Zarco told me about how God appears to each of us differently, and I decide to ask Mama what she thinks Hitler finds most beautiful about the world.

She looks up from the mop she’s pushing across the floor. “I bet it would be the sound of his own voice. But in that, Sophie,” she adds, fixing me with a disgusted look, “he’s hardly alone.”

Contempt for her fellow human beings? Worth nurturing, so I ask her to elucidate, but she says that she was just babbling and that I better hurry up with the leeks, which makes me roll my eyes since Hansi is only just starting to peel his second potato.

Rini is more forthcoming. “Hitler would love pulling off the wings of a live bird,” she declares. Then she flips her hair casually off her forehead and breaks off another square of her chocolate bar. “Want some, my dear?” she asks, not a trace of horror on her face.

Sometimes that girl scares me.

The 19th of September is my fifteenth birthday. Tonio gives me a gift wrapped impeccably in blue-and-white-striped paper, which means his mother did it for him. The card says, “For Sophie, who’ll make us all proud.”

I hug him hard, because his words mean he understands—and supports—my desire to excel. I find a sketchbook inside—fifty sheets of smooth, heavy paper, the best I’ve ever had.

“It’s perfect!” I beam. “Thank you.” I want to say more but I also don’t want to frighten him off—my leitmotif with men.

No turning back: that’s what our continuing embrace means. At least to me. Who knows what a hug might signify to a sixteen-year-old boy who can’t wrap a present by himself?

At supper, after I blow out the candles on my birthday cake, my parents give me a set of twenty-four colored pencils made in Czechoslovakia by Koh-I-Noor. Which means that they and Tonio conspired together to buy complementary gifts. A very encouraging sign!

On Sunday, the 2nd of October, I learn some more about what The Ring has been planning, and I get my first glimpse of the road we are all about to take into our future. It’s the day after Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, and Mr Zarco, eager to celebrate in style, takes scissors to a swastika flag and hangs the tattered fabric out his window facing Prenzlauer Allee. He does an excellent job. I find out later that other members of his group are shredding flags all over Berlin and its suburbs.

When Papa and I return from the bakery with fresh bread, we see how Mr Zarco’s handiwork has turned the black, red, and white banner into spaghetti.

“Good for him!” Papa exults.

Mama disagrees hotly. “To make a public spectacle … it’s embarrassing.”

“Why?” I ask, pausing as I munch my toast. I give her an innocent look, though I’m well aware I’m playing havoc with her emotions.

Papa and I both stare expectantly at her. Even Hansi is gazing at her above his oatmeal, though maybe he’s only trying to communicate telepathically with her that he wants more milk.

“Because it happens to be beneath him,” she tells me, escaping to the sink to wash her hands.

“Why is it beneath him?”

“Sophie!” Mama snaps, turning back to me with vengeful eyes. “I hope for the sake of your future husband that you one day learn some restraint.”

Papa holds his finger to his lips when I glance at him for support, so I stomp into the sitting room. Mama’s testiness gives me the perfect excuse for slipping out of the apartment, and I ease the front door open and dash down the stairs, across the courtyard, and up the back staircase. I’ll pay for my rashness later, but for now I feel only a wind of joy blowing through me.

Tonio has been waiting for me and we race to the street. On turning the corner past our building, we spot Mr Zarco’s protest and Tonio’s lips twist disdainfully. “That sort of affront makes you wonder if the Jews even want to be part of the new Germany we’re building,” he says.

This is the first time Tonio has used we when referring to the Nazis. I’m upset, but overlooking such a major flaw also makes me feel magnanimous.

“I have a special present for you,” he adds as we head off, “but it’s in the Neue Museum.”

“What is it?” I ask, thrilled by his surprise.

“Patience!” he commands, and he grins in that wily way that makes my breathing deepen.

We make our way across Berlin, which at the moment is a journey into a myth about a boy and a girl walking beside a river of dark glass—the Spree. On Königstraße, across from the main post office, I decide to play hide and seek, and I duck in through the open doorway of an out-of-business restaurant with fake palms painted on the windows. In richer cities like Paris and New York, do the doors to ruined lives stay boarded up? Here, our homeless and unemployed knock padlocks off doors with old shoes and set their bruised suitcases down inside abandoned shops, their mop-haired kids in tow. We have an entire second city built by the wretched inside the bankrupt, and if you are willing to take a risk, you can look down into this underworld any time you like.

Six filthy mattresses smelling of mildew are spread on the floor, an equal number of old blankets piled neatly on top of one of them. In the far corner spreads a mess of dog-food cans and old newspapers. Behind a smashed-up table and under a copy of the Morgenpost from July, I find a black violin case. Inside is a letter addressed to Heinz from Greta and underlined copies of Erich Maria Remarque’s two novels: All Quiet on the Western Front and The Road Back.

“Take a look at this,” I tell Tonio eagerly, feeling kinship for Heinz. “Maybe he’s performing in Alexanderplatz, playing Beethoven and Brahms for his supper.”

After only a cursory look, Tonio sneers. “Remarque is an enemy of the people,” he declares.

I don’t even try to answer that.

A broken window at the back spreads a sheet of light across the floor and onto a wooden counter where the owners must have set out Sachertorten and other cakes in better times. Tonio doesn’t fight me as I lead him there, and we don’t say another word, because I’ve slipped my hand through his zipper. As I push him back against the counter, his eyes flutter close. I drop to my knees, eager to have his hands pressing down on my shoulders. The silence, dark and fragile, is ours. Even the clutter belongs to us, because it’s proof that our need for each other can resist the vagaries of time and place.

I love the color of his penis—milky brown, but pinkish near its tip—and the silly way it hangs down when it’s not yet fully hard. His balls contract like magic when I cup them, and he moans as if he’s being flailed. Why didn’t anyone ever tell me how easy it was to subdue a boy? I take the pearl of fluid at his slit onto my fingertip and bring it to the tip of my tongue. A small gesture, but it makes him look at me so hard that I know he’s my prisoner.

“Am I to be a part of the new Germany?” I ask Tonio.

A swooning young man—his head arched back and neck straining, his fingers digging into my shoulders—who can still laugh. What more could any girl want?

“Please, Sophie … You’re breaking me in half.”

I love the thick, pungent taste of his need for me. And the size of his power.

After I’ve taken all he’s got for me and he’s shriveled back into a wrinkled acorn, I lick him clean, because I can’t get enough of my new sense of adulthood, and because we both need to see what we might lose if we’re not careful.

Sex as our detour around the little man who shouts, Tonio’s contempt for Erich Maria Remarque, Georg’s death, and all the other things that might separate us. An unusual escape route, I think at the time.

Arm in arm, we amble up the long staircase of the New Museum to the second floor and head into the Engraving Rooms, where Tonio stands me—hands again on my shoulders, but this time gentle—in front of a Dürer drawing of his mother.

“You need to see a real live Dürer if you are going to keep improving,” he says by way of explanation, in an adult voice that’s very impressive.

He takes a step back so I can look at it alone. This discretion is new to him. Maybe our devotion to each other is tugging him toward manhood.

According to the indication beside the sketch, it has been 418 years since Mrs Dürer posed for her son, and yet she is still peeking out at the world from beneath her headscarf—captured forever in a moment of wary anticipation. I step closer, into the field of silence and nervous emotion that her face creates in me. Can she be wondering something so unimportant as who is about to come in her front door? Will her husband demand his lunch and a stein of beer? Maybe her son is the one whose footsteps she hears, and he is about to show her his latest canvas. More exciting for her, of course, but at times it must seem that the rivalry between son and father for her attention will never end. I see that tug in different directions in her tightly sealed lips and straining eyes, and maybe it’s why her son has drawn her midway between anger and laughter. My Mother’s Two Roads, he might have called this sketch.

Strength appears in her gaze, as well—a glint of power, a dominance over herself and her home, and her son; though it’s 1514 and Albrecht is already famous, she is aware she holds his heart in her hands. That’s the womanly power she has, and that I am beginning to acquire over Tonio.

“I’ll never be that good,” I tell him when he steps beside me.

“You’ll go as far as you can.”

He holds my arm and kisses my neck. In his touch, I feel why I’ve made only tentative attempts to draw him. I can’t give form to Tonio yet—he’s still too much a mystery to me, and too essential to my well-being to risk fixing on paper. A poor likeness—or even a good one—might be the magic that breaks our spell. No, I won’t try to draw Tonio, not even after we’re married. And what I don’t sketch will remain sacred.

We walk back home in the early afternoon. By now, residents from all over the neighborhood have come to see the ruined flag, our first tourist attraction. I begin to believe that having Hitler around might finally put our dull little street on the map!

Tonio kisses me goodbye below Mr Zarco’s window because he and his parents are visiting his aunt and cousins that afternoon. I soon strike up a conversation with a Jewish family from Dahlem, a neighborhood ten miles across the city. They were on their way to relatives when they spotted the flag. Their burgundy Ford is parked across the street and has drawn a crowd of screeching kids because the family’s bearded old wolfhound, Pfeffer—sitting tall in the driver’s seat—is happily licking the hands of anyone reaching inside the window.

“Sophele!” Mr Zarco suddenly calls down. “What a nice surprise!”

I shout up that I want his autograph, which makes him laugh with such pleasure that I’m proud of myself for the rest of that day.

“A good idea I had, no?” he calls down to me enthusiastically.

As I shout up my agreement, a skinny, spectacled photographer wearing a nametag saying that he works for Der Stürmer begins to snap away at our neighbor with a tiny black camera. Emboldened by the tourists around me, I step up to him. “Excuse me,” I say, “but I don’t recall Mr Zarco giving you permission to photograph him.”

He gives me a look of violent disdain and goes back to his work. My pulse races when I think of swatting the camera out of his hands, but I don’t have the courage.

In such seemingly insignificant ways did I slip away from myself, I now realize. If only Rini had been with me; she’d have grabbed his damn camera and hurled it against a wall, then casually offered me a square of chocolate.

“Forget the mischief-maker,” Mr Zarco calls down, flapping his hand. “He’s harmless.”

So it was that he, too, let his guard down.

As I would later be told by Mr Zarco and the Munchenbergs, sometime after midnight, three men throw bricks through Mr Zarco’s window. Raffi and his parents hear the breaking glass and peer out their kitchen window in time to see them praising each other’s aim. Raffi is sure they’re wearing the brown shirts and flaring trousers of the S.A., the Nazis’ private army.

Mr Zarco bursts out of sleep, terrified, then rushes to his window and sees the men laughing, then running away. He sits on the end of his bed, puts his head in his hands, and sobs as he hasn’t since his wife’s death, nine years earlier. After sweeping up the broken glass, he throws a towel over any tiny shards that might still be there and lays the bricks one on top of the other on his night table, next to his Yiddish copy of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. He’s shivering from the chilly wind rushing in through the shattered window, but he takes off his nightshirt, wanting the cold to wrap around his naked body, to feel the discomfort of a city—his city—becoming a castle under siege. When he slips back under his eiderdown, he imagines that he is snuggling with his wife and making a home for himself in her. From experience, he knows it is the only way he will be able to sleep.

He wakes three times during the night, and each time he is pleased that he has provoked a reaction from the Nazis. The brisk autumn wind now seems to confirm that he has acted bravely. Sitting up during his last bout of sleeplessness, he stares at a linden across Prenzlauer Allee as if its leaves and branches contain the answer to where all of Germany’s political turmoil is leading. And he prays, his lips moving over the syllables as quickly as he can, as if to outrace destiny.

To my solemn disappointment, I sleep through all the excitement. Tonio does too.

Two policemen come the next morning to interview Raffi Munchenberg and his parents, and Mr Zarco. They take away the bricks as evidence of the crime. They also order our neighbor to remove his flag, alleging that he is creating a public nuisance.

He cedes to their wishes, but puts it back up on Tuesday morning. An emergency assembly of tenants reluctantly votes that evening to ask Mr Zarco to refrain from any overt displays of political opinions.

“I’m sorry, but the flag stays,” he tells their delegation.

That’s when Dr Lessing, who lives in the apartment opposite the old tailor’s, says, “Until Germany resolves the Jewish question once and for all, it’s best for you and your people to make no more trouble than you already have.”

“Oh, is that right? Rest assured, Dr Lessing, I haven’t even started making trouble yet!” Mr Zarco replies menacingly. “And I would advise you to keep out of my way.” He then invites his guests to leave.

Papa was a member of the delegation and tells me all this before tucking me in. Now, he’s not so sure that our old neighbor is acting sensibly. “Except in an emergency, individuals ought not to work alone or even in small groups,” he says, speaking in that artificial voice that means he’s quoting Marx or one of his other heroes. “Party leadership should determine the timing and manner of all protests.”

“Maybe for Mr Zarco this is an emergency,” I reply.

“It’s my curse to have so quick-witted a daughter,” he says, batting me playfully on the nose like a cat.

The police are back on Wednesday. In raised voices, they threaten to arrest Mr Zarco. And history repeats itself; he takes in his flag only to put it back out at sunrise.

Later that morning, as he walks to his small factory on Dragonerstraße, someone bumps into him from behind. Annoyed, the tailor turns around, and a man—slender, wearing a stylish woolen coat—whacks him in the gut with a plank of wood, breaking two ribs.

Mr Zarco falls to his knees, gasping. A second thug—overweight, with a double-chin and mustache—hisses that he is a parasite. He grabs our old neighbor’s hair and tugs him facedown onto the sidewalk, so hard that his chin meets the pavement with a thud. For a time, Mr Zarco is unsure as to where he is. The last thing he recalls is the word Jew whispered in his ear as if it were composed of heavy sand. Is he awake or dreaming?

At the Augusta Hospital, doctors in the emergency room bandage Mr Zarco’s broken ribs. A nurse stitches up the deep gash on his chin. Feeling the tug of the string, he decides it’s delightful being helpless in a woman’s hands again.

The next afternoon, while Mr Zarco is snoozing, a cleaning woman lifts his tweed coat off the chair it has been resting on, and page two of the current issue of Der Stürmer tumbles out of the pocket. It’s folded in four, and when she opens it up, she discovers a photograph of him has been printed near the bottom. She puts it on his night table for safekeeping. Stirring from the sound of her footsteps a few moments later, Mr Zarco reaches for his water glass, and his hand brushes against the newsprint. Sitting up, he sees himself leaning out his window next to the ruined swastika and reads the caption: A Jewish parasite on Prenzlauer Allee in Berlin desecrates our glorious flag.

The thugs must have identified him from this clipping and stuffed it in his pocket to be certain he understood that they were avenging his affront. But at least a dozen flags were shredded all over the city, so why did Der Stürmer print only Mr Zarco’s picture?

A few days later, when I see the photograph, a tremor shakes me, because I’m thinking: No matter what else he does in his life, Mr Zarco will always be on page two of issue Number 42 of that wretched newspaper and the Nazis will always know where he lives.

K-H, Mr Zarco’s photographer friend, knocks on our door that evening and reassures us that our upstairs neighbor is recovering well. My mother brings him a cup of the coffee she’s just made. K-H wears red suspenders and a white bow tie. Very classy. And today, his cologne smells of violets.

“Isaac is already complaining about the chazerai that the hospital calls food,” K-H tells us, laughing in the relieved way of people who’ve been crying. “You understand?”

“No,” my mother says, because she isn’t used to his deaf person’s voice or his Yiddish, so I translate chazerai, pig-food, into German; it’s a word Rini uses all the time.

Gazing at me over his steaming cup, he says in a somber voice, “Sophie, Isaac wanted me to tell you that you’ll have to water his plants until he comes home.”

“His plants?”

“He said you agreed to help—to water his pelargoniums whenever he was away.”

Tears of gratitude flood my eyes. Worse, I can’t assemble a voice to explain myself.

“Didn’t you hear? Mr Zarco is going to be fine,” says Papa, pressing reassuring lips to my cheek. Mama sits beside me and combs my hair with her fingers.

When I’ve calmed down, I lead K-H to Mr Zarco’s apartment. The photographer asks me about my favorite subjects at school. He speaks in short sentences to better manage all those words he cannot hear. I talk about Frau Mittelmann, but my words float over the image of Mr Zarco lying facedown in his own blood.

“Sophie … ?” K-H is holding the front door open for me. Empty of guests, the sitting room is a landscape of books. The Persian rug is gone, too, revealing a dark parquet floor. I feel like a child in a fairy-tale forest, facing the unknown alone. I’d like to knock every last volume off the shelves. Destruction as a way to prove that nothing now can ever be the same.

And Tonio sympathizes with these hooligans …

My face must give away my despondency, and K-H pours a little schnapps into a shot glass for me. “Drink this, sweetheart,” he says as if it’s an order, and as the burning descends into my belly, he adds cheerfully, “Isaac won’t be stopped by broken ribs. Now, I’m going to leave you for a minute. I have to pack a bag for him in there.” He points to the bedroom. “Isaac needs something to read. And he needs more tobacco. So you just water the plants and stop worrying.” He plucks his suspenders and smiles handsomely.

Am I evil for wondering about what his penis looks like? “I’m all right, just do what you need to do,” I assure him.

Four pink and white pelargoniums huddle under the windows in the sitting room, as quietly exuberant as Mr Zarco himself. They’ve been planted in canary-yellow ceramic pots and arranged on a slate platform. I squat down by them and pull off the wilted flowers, wanting the plants to be perfect for his return. I find a rusted iron watering can under the sink in the kitchen.

When the flowers have soaked up all they can, I pass by the guest room on my way to Mr Zarco’s bedroom. My first look at Wonderland. Twenty blue and green glass fish—each the size of my hand—are dangling from the ceiling, spreading colored shadows around the room, which is a treasury of paintings and drawings. A watercolor of a city of domes and minarets catches my eye first. It’s painted in browns and grays under a blue-blue sky, as if even bright sunlight cannot lift the gloom from the city. Istanbul, Mr Zarco will later tell me.

Just above it is a drawing of a bride and groom soaring through the air. Behind the love-struck couple is a cockeyed village centered by a garlic-bulb Orthodox church. My first Chagall. I will study it many times over the coming years, and what never ceases to amaze me is the sense that the artist has reproduced an entire world in a five-by-seven sketch. It’s one of the works that changes my life.

Near the window is the drawing that becomes my favorite, however. It’s an Otto Dix portrait of a slender, kindly looking gentleman standing by an open window and wearing an elegant but threadbare coat. The man, in his sixties, is aware he is being sketched, and his lips are pursed in gentle amusement. His long, spidery hands are beautiful—the hands of a father who writes weekly letters to his faraway children with an antique pen, I fantasize. It’s his goodness that the artist has sought to capture I’m sure of it. And I place his name in a special spot in my memory when Mr Zarco tells it to me a few days later: Iwar von Lücken, a German poet and friend of Mr Dix.

As I step into the doorway of Mr Zarco’s bedroom, K-H waves me in. Only one painting is on the walls—a watercolor of a shimmering topaz-colored forest under the purple sky of dusk. The trees seem to be made of fire. Like a premonition of destruction—or rebirth.

Below the painting is a mahogany desk covered by a blotter of faded green felt. On it are three notebooks of black-and-white checked oilcloth, like those used by schoolchildren.

“Sophele,” K-H says gently, coming up to me, “I wanted to say something to you before. This country of ours is going through a difficult period, but everything will be all right in the end.” He kisses my brow. “You’re too young to worry. Live your life.”

What good luck I’ve had to meet such a considerate man, I think, but he seems to have forgotten that I’m at an age where nearly every experience can grow thorns.

“Now the disagreeable part,” he says, wrinkling his nose. “The flag has to come down.”

“No, please. If you remove it, then Mr Zarco’s protest didn’t mean anything.”

He tilts his head as if weighing his options. “No, next time they might throw firebombs. Or murder him, like they did Georg. We can’t take the chance.”

“Did you know Georg well?” I ask, and when he nods, I add, “Did you like him?”

“Yes, though he wanted to use violence against the Nazis. I wasn’t so sure.”

“Is Mr Zarco against violence?”

“He’s not sure either.”

“And Vera?”

K-H laughs, then crosses himself as though warding off evil. “I’d never presume to speak for Vera.” He brings his fist down on his head like Buster Keaton. “She’d clobber me.”

So maybe Georg was murdered by the Nazis because he wanted to start using violent tactics against them. “Do you really think Georg was strangled?” I ask. “I mean, there were no signs of a fight.”

He shrugs. “Maybe I’ll show you the pictures when you’re a bit older—if your parents give me permission, that is. Then, you can make up your own mind.”

“What pictures?” I question.

“Vera was the one who found Georg dead. She had me take photos, because she wasn’t convinced the police would investigate properly. She wanted proof of those swastikas drawn on him. She was very upset, as you can imagine.”

“And where are the photos now?”

“Isaac has them.”

“Do you know where he keeps them?”

“Yes,” he grins, eyeing me suspiciously, “but I’m not going to tell you. We probably shouldn’t even be talking about these things.”

“K-H, I’m fifteen years old,” I declare. “And … and I knew Georg. So I think I have a right to see the pictures, especially because I’m worried about

Mr Zarco and what’s going to happen to him and … and all the Jews.” Seeing that he’s still going to turn me down, I add, “My parents let me see my father’s mother in her casket when I was only twelve. I didn’t get the least bit upset.” That’s a lie, since I spiraled down into nightmares for days afterward, but it’s for a good cause.

“Are you sure?”

When I nod, he heaves a sigh of resignation. Men can be such pushovers.

Mr Zarco keeps the photos in an envelope in his desk drawer. The first is of Georg’s pale and slender face. His cheeks show a dusting of whiskers, and I’m struck by his high, flaring eyebrows, which seem too bushy for so thin a man. A swastika reaches its evil arms across each cheek, like a grasping spider. A smaller one sits at the center of his forehead. There are no marks on his neck.

Georg looks older than I remember him, but he was in makeup then, dressed as Cesare.

The second picture is of his hands, a rushed, uneven swastika in each palm. I’d bet the killer made these ones last—as an afterthought, while fearing being caught. So maybe the murder wasn’t planned.

“Was it creepy taking pictures of a dead man?” I ask K-H.

“No, I’m used to it. I was a police photographer for several years.”

As he goes to the window to take down the spaghetti flag, I rush to him and reach out for his shoulder so he’ll turn to me. “K-H, even if the rest of Germany is stuck in the Middle Ages, this is Berlin. Mr Zarco should be able to do what he wants to here.”

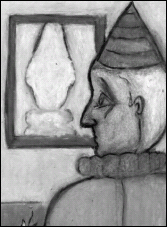

I catch Hansi wondering about his reflection

He shakes his head. “That’s the point, Sophie—he can’t. Not anymore.”