![]()

Twenty thousand books are burned by university students in Berlin’s Opernplatz on the 10th of May. Sigmund Freud, Max Brod, Alfred Döblin, Klaus Mann, Peter Altenberg, Oscar Blumenthal, Richard Beer-Hofmann … If you don’t know all their names, then the Nazis succeeded in turning more of our culture to ash than you may want to admit.

Tonio leaves a red rose for me on our doormat every Saturday morning, together with a note, which he always signs, Faithfully yours. My father and mother are impressed by his loyalty, and they let me see him again long before my three-month sentence has elapsed.

I drag Tonio to see Marlene Dietrich in Blonde Venus in early June, and as revenge, he makes me come with him to see King Kong. We take Hansi with us, since I don’t see why I should suffer alone.

“The era of Jewish intellectualism is now at an end,” says Dr Goebbels in the newsreel before the film. “The future German won’t just be a man of books, but a man of character.”

Our Propaganda Minister is addressing a throng of students exalted by this chance to destroy a thousand years of poetry and prose they never wanted to read in the first place. Or could it be that Dr Goebbels is talking directly to that pile of ash in the center of the screen—the smoldering jumble that was Germany’s culture until three months ago? It’s hard to tell from the camera angle and no one would put it past that madman to have a conversation with cinders. As Isaac once told me, “Goebbels’ mind is urine.”

“Absolutely wonderful!” Tonio whispers to me as the minister reaches his final cadence, which means I’m in love with a young man who likes the scent of piss.

My patriotic boyfriend then moves my left hand over the expanding bulge in his pants, confirming a little-known fact that no one will ever write about, not even after the war: Dr Goebbels knows how to arouse the men of Germany better than the most experienced Neapolitan prostitute on the Kurfürstendamm. That’s his most intimate secret, and ours.

Then King Kong comes on and Fay Wray is pretty in a mousy way, and the towering gorilla is terrifyingly realistic—almost as realistic as that other wind-up toy, Dr Goebbels—and Tonio, Hansi, and I, and everyone else in a thousand theaters across the country can be scared of something that will end in less than two hours, and forget about the importance of books for a while. Or forever, depending on whether we are men and women of character.

* * *

One afternoon after school, Tonio meets me so that we can hunt for old car and movie magazines in the back room of an overstuffed junk shop on Karlstraße that we sometimes explore when I can bear the dust. Afterward, since we’re only a minute from Julia’s shop, we go there, and I explain to Tonio that I met her and her son at Isaac’s Carnival party, though I’m careful to call him Mr Zarco. We stand across the street, under the awning of a café.

“What are you up to?” he asks me suspiciously.

“Nothing. I just want to watch for a while.”

Julia helps a man in a derby hat choose tea for whatever problem has made him touch his elbow twice. She’s wearing a brown woolen skirt and black blouse, and her dark hair is bound tightly on top of her head. Unless the traitor in The Ring slips up, I realize, we’ll never find out who he or she is. So I will have to start things in motion …

I begin to track Julia’s movements over the next weeks, always in the afternoon, but only irregularly because of commitments at home. She eats lunch in her apartment, which is directly above her shop. An assistant—a pale, petite young woman—substitutes her at this time but stays for only an hour and a half. At six in the afternoon, Julia closes up and fetches Martin. Often pausing for coffee at Wolff’s Café on Lothringstraße, she walks to a whitewashed, five-story apartment house behind the Bötzow Brewery on Saarbrücker Straße, where the stink of hops and malt is so intense that it brings tears to my eyes. A friend there must tutor the young man during the day, or simply watch over him. The mother and son then walk home leisurely, occasionally arm in arm, though Martin sometimes pauses at shop windows, his hands flat against the glass. They talk as they walk and Julia’s laughter is frequent and free. She seems to be a woman who has gotten what she wanted out of life. She usually buys Martin a treat at the Hengstmann Bakery, just next door to Wolff’s Café. He adores cream puffs, and she keeps a white handkerchief in her leather bag to wipe his face afterward, though he sometimes insists on doing it himself and shakes his hands as if they’re on fire when he doesn’t get his way. Anyone can see she is devoted to her son. Sometimes she watches him as he runs ahead of her, his arms flailing, and her eyes aren’t worried, like my mother’s used to be. They’re radiant with an emotion I’d never have expected—admiration.

I try to remember that a contented woman who adores her son might still commit a murder—could even be conspiring with the Nazis. After all, we all have a double life in Germany. And yet, I soon begin to doubt she had anything to do with Georg’s death.

Julia’s days are confined by a small area of Berlin. Only once does she make a deviation. In early June she fails to fetch Martin at the usual hour and instead walks east down Oranienburger Straße, glancing up briefly at the shimmering golden dome of the New Synagogue. She threads her way through the confusion of shoppers in the Hackescher Market and strides up Rosenthaler Straße like a woman on a mission. As I navigate past the pushcarts, apologizing to the people I bump into, I realize with an electric jolt where she’s headed and what might be about to take place. So I slip into a beer garden before I’m spotted. After all, if my hunch is correct, then Isaac or Vera could be right behind me.

I force myself to drink a glass of wine so that I’m not tempted to jump up too soon. My legs are tense with the need to catch up to Julia. But being caught now would ruin my plans.

I find Karl’s Cellar as dingy and dimly lit as ever, which is a bit of luck since it reduces my chances of being spotted. I’m standing just inside the front door, which is separated from the dining area by an American-style bar. Far at the back, submerged in the watery light from the table lamps, are the people I’m after. They seem elongated, almost dreamlike, as though they’re trapped in a canvas of red and reflective black, and a kind of liquid gold that burnishes their skin. They’re seated round a long rectangular table, and I hold my hand above my eyes as I count them so no one can see my face. Twenty-two members have arrived. Vera is easy to spot, a head taller than everyone else. Next I notice Isaac, and seated on his right, chatting with their hands, are K-H and Marianne. Heidi doesn’t seem to be there, but Rolf is seated across from Vera, who’s whispering something to Roman. Julia is there, too, of course.

A big-bellied waiter comes up to me right away and tells me that the restaurant is closed until seven-thirty, which is an hour away. I tell him in a beseeching tone that I’ve agreed to meet a friend here, but he replies coarsely that I’ll have to wait outside. It’s plain from his tone that he is protecting The Ring.

“Please, I have a bad head cold,” I tell him. “Just let me wait here a few minutes.”

“I’m sorry—Karl makes the rules and I can’t break them.”

“Then can I speak to Karl?”

“You are speaking to him,” he shoots back—unfortunately, without humor. He raises his arm to prevent me from entering. “Please, Fraülein,” he says forcefully, “just wait outside.”

The last thing I see before leaving is a black hat being passed around the table, brim up, and K-H placing his hand into its hollow.

On the way home, I realize they must have been drawing lots of some sort, which means I’ll have to defy my parents and visit Isaac to find out why. Late the next afternoon, I spill a full bottle of milk down the sink when Mama isn’t looking and tell her I’m off to Frau Koslowski’s grocery since we’ve none left. Rushing like a madwoman, I slip off to Isaac’s apartment, but he isn’t in. Over the next few days, he never answers my knocks. I worry that he has been arrested, but Mrs Munchenberg tells me that he asked her to take in his mail for a few weeks, so he must be on a trip.

I hope Vera or some other friend will come to our apartment house to water Isaac’s pelargoniums so I can ask after him. But I never spot anyone.

Two more weeks pass without any word from Isaac. Meanwhile, in late June, Hansi’s headmaster gives us the news I’ve long been fearing, that the boy will not be admitted back to school after the summer vacation. “If he doesn’t speak or even react to what is happening in class, what are we supposed to do with him?” Dr Meier tells us.

We have no answer, and Papa tells Hansi—kneeling down to his height to soften the blow—that he’ll be spending his days at home now. Does my brother care? I can’t tell from his hollow stare. I’m sure, however, that he’s fading from us. Still, Mama tells him cheerfully, “Don’t worry, you’re far better off here with me.”

Probably just what the witch told Hansel and Gretl, I think.

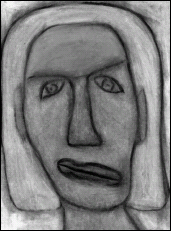

Once Papa gives me permission to open my sketchbook again, I get Hansi to pose for me all the time. Among other benefits, it helps me count off the days while Isaac is gone without growing frantic.

Monet had the water-lilies of Giverny and Van Gogh had the sunflowers of Arles, and a moderately talented girl living on Marienburger Straße has a mute little boy with long earlobes and silken hair. For hours at a time I draw his face and hands, and his elfin feet, which look like they were made for jumping down rabbit holes after his own never-to-be-revealed ideas and opinions. Sometimes in the early morning, I try to draw him inside the spangled dust swirling around us. Fairy powder making us the only two people on earth. If only I could grab hold of my brother as he dives into his own world—his own personal Araboth. So many answers might be waiting for me there: how to get Raffi home and keep him and Isaac safe, and maybe most important of all, how to make my real father return.

I sit by his bed when I have insomnia, which is almost all the time. Hundreds of sketches of a boy with arms and legs at spider angles, or curled into a ball, his covers on or off, snoring, snuffling … Once, he even talks in his sleep, and though his words are too muffled to understand, I think I hear the word Finland.

I sometimes put my hand on Hansi’s head while he is in dreamland. I feel the fragile softness of his breathing entering into me. Maybe his very presence—his innocence—is protecting me, keeping me sane. Is that what I’d see if I looked below our surface?

After school ends for the year, Mama orders me to join the Bund Deutscher Mädel, the Young German Maidens, so starting in July, two afternoons a week, I train my public double for her place in the Fatherland. Our uniform consists of a knee-length, dark blue woolen skirt with a double pleat in the center, a white blouse with two breast pockets, and a black neckerchief. In it, I could be Gurka. No, let’s be honest, I am Gurka! Rini may be Jewish and therefore a bloodsucking insect, but at least she doesn’t have to suffer the indignity of looking like she’s training to become a Prussian prison guard.

Thankfully, we Maidens have to wear our outfits to school only on Hitler’s birthday and other such happy occasions, so most of the time I can dress as though I were still living in the twentieth century. As I might have predicted, Tonio and my mother both adore me in my uniform. When Mama sees it on me for the first time, she clasps her hands together and tells me I’ve never looked more charming. A statement meant to divert me from understanding that what’s truly beautiful to her is my being forced to wear such wretched things, but what would she think if she knew that my boyfriend asks me to dress in my uniform at his father’s private apartment? A Young Maiden on her knees for Germany … That’s the heroic sculpture Tonio makes with his bowed back and racing heart every time we close his father’s adulterous door behind us. I don’t mind in the least; that handsome young man’s polishing of my desires may be the only thing saving my mind. And the joy he thrusts inside me when I’ve got my eyes closed and am pleading with him to open me as wide and deep as possible cannot yet be used as evidence against me in any of the Führer’s courts.

More than anything else, I love the power I feel when he is in my mouth, that dirt-pure sense of being a girl worshipping an altar older and far more meaningful than Hitler, Göring, and all the other lesser divinities who’ve created this world where I have to wear a swastika armband to school, and make believe Rini doesn’t exist, and stand outside Isaac’s door without daring to knock because someone with a mind fit for a latrine has decided that culture is bad for the German soul. I adore the patina of Berlin grime in our dimly lit, one-room shack in the fairy-tale forest we make with our own bodies, with its spider webs in every corner and its gray fungus-muck on the shower curtain, and the lavender-scented foot powder left by Tonio’s father’s secretary on the chipped red bathroom tiles. In this grotesque refuge from proper behavior that’s not on any map in my parents’ possession, I’m using every forbidden trick I’ve got—and I’m discovering I’ve got plenty!—to please a young man, one who may or may not be worthy of me, as it turns out. Maybe that determination ought to matter to me a great deal, but it doesn’t, because he’s as breathless and exalted as God was when he first spurted the universe into existence, and I’m doing what’s been done by women since Adam and Eve first were exiled for coiling like snakes around the knowledge of good and evil, and giving myself in ways that every father in the Fatherland would despise.

Each stain on my Young Maiden blouse and skirt is my victory not just over my mother and father but over my country. You think that’s crazy? Then consider yourself very fortunate, because you didn’t live in Berlin in 1933.

Sex may be the only hope in a dictatorship like ours. Not that the Maidens know anything about such subjects. We sew and sing, bake cakes, learn how to keep our fingernails clean, and practice the proper Hitler salute. All essential for the German homemaker. We also read about ourselves in Das Deutsche Mädel magazine. Each issue is full of lively news of girls scaling the Alps, for instance, but what they do when they finally make it to the top of Mount Wendelstein is anybody’s guess. Surely one or two of the more fame-hungry girls might at least stumble from exhaustion over a cliff to give the readers something captivating to read about, but no such luck.

When Maria Borgwaldt, our group leader, inspects me and the other new girls after our first week of training, she strongly advises me to wear my hair in plaits. “Good-looking and practical,” she tells me, tugging on the ends of hers like two bell-ropes, which may be her way of either remaining alert or of reminding herself not to say what she really thinks.

Maria speaks in a voice so sincere that it is a miracle God doesn’t appear to her and order her to stop talking for Him.

“I’ll think seriously about braids,” I tell her, but we both know I mean no.

The next week, as I’m waiting my turn to shimmy up a rope in the school gymnasium, she pulls me aside to give me private advice. We stand arm in arm, which is a privilege for me, since she is renowned for having mastered all of the more difficult techniques in our Young Maiden Cookbook. Our Lady of Soufflés, is what I call her. Because Maria’s personal soufflé is never going to fall, of course.

“Sophie,” she tells me, “you wouldn’t want your hair to slow you down or get caught on something. That could be dangerous. You really must braid it.”

Daring to reveal a crack of light from behind the Semitic Wall, I reply, “Do you really believe that letting my hair stay loose is keeping me from setting a world record in the long jump?”

No smile. “That’s not the point, Sophie,” she says, as if I ever thought it was. “Even if you only jump one centimeter further, that could make all the difference.”

“To whom?” I ask. Now that I’ve started talking like myself, I can’t seem to stop.

“To the Führer.”

I look around. “He seems to have stepped out for a smoke.”

“I don’t think he smokes.”

“Cigarettes and cigars, maybe not, but he loves smoking books.”

“What are you talking about?”

Maria looks like a deer paralyzed by car headlights. A dangerous sight; those blue eyes of hers are so empty and pretty that I might just fall in and never find my way out.

“Forget it,” I tell her.

If Maria were to lose her virginity would she gain a sense of humor? A question worth asking of Martin Heidegger and all the other philosophers who are sleeping now in Hitler’s bed.

In our studies, I learn that we will be expected to have hordes of happy children and obey our husbands. Aryan rabbits with our legs open. Wearing invisible collars around our necks and chains on our ankles—the Maiden uniform that no one sees or even imagines. Except maybe Tonio: perhaps it’s the clanging of my fetters and metal scent that gets him panting like a dog. If so, good for him!

We learn that Maidens may not spit, curse, or get a tattoo. Maria tells us that such debauched habits brought down the Roman Empire. As did frolicking in bed before marriage apparently, because she also implies—using terms so vague that a few of the girls ask me later what I think she may have meant that—it is strictly verboten to take our boyfriends in our mouths, let alone allow them inside our baby-making apparatus.

Obviously, any girls trying to model themselves on Marlene Dietrich aren’t going to make it in the Maidens. But I am, despite my wry contempt. Within a few weeks, I’ve forged friendships with two of the more cynical girls—twins living on Senefelder Platz named Betina and Barbara. I’ve also earned a merit badge—a brass eagle—for embroidering swastikas onto men’s woolen hats. I considered making the messiest ones in the history of the Reich, but Papa—who watched me sewing them at home—told me that since the hats were going to be distributed to Berlin’s poor, they had to be perfect. He’s obviously still on the side of the proletariat, who are now called the Volk.

I also win a third-place medal for running the hundred-meter dash faster than everyone except Ursula Krabbe, who has such long legs that she is obviously reincarnated from a stork, and Maria herself, who has her hair braided and fastened in a tight knot, and who therefore had an unfair advantage against the rest of us.

I’m also not as bad at javelin throwing as I thought. My best: twelve meters. Excellent news for our defense forces should we be attacked by short-sighted Finns escaping from Hansi’s dreams. Or should the Jews rise up against us, as Maria warns.

I begin to feel reasonably comfortable with the other Maidens until a physician named Herbert Linden gives us a lecture on Racial Hygiene, complete with slides of the kind of men we must not marry if we are to keep the Aryan race pure. The Jew is, of course, Number One on our list of verboten suitors, and we see a mug shot of a fat-faced specimen in profile so we can better see his monumentally hooked nose. Number Two is a swarthy, smirking Gypsy whom we see head-on so that we can remark his greasy halo of shoulder-length hair. Last but not least of these inferiors is a bare-chested Negro sitting on a stool while a man in a white coat uses calipers to measure his thick lips. Three and a half centimeters of proof that he is beneath our contempt. The girls groan each time another beastly candidate for our German maidenhood comes up, and nervous laughter breaks out when we see dwarfs and hare-lipped men. But nothing compares to the hoots of horror and giggles when a hump-shouldered giant with a cruel, caveman face appears against a background with a grid measuring his height—two meters seven. I’m as silent as death because he could be Vera’s brother.

Later in the slideshow we hear about the dangers of marrying men who look normal but who are anything but—idiots, epileptics, syphilitics, the congenitally deaf and blind. And those who live in their own universe, whom Dr Linden calls schizophrenics. One of the types he describes is Hansi, which makes my legs quiver as if I need to run and never stop.

Isaac returns during the third week of July. He’s been gone for over a month. “Thank God, you’re safe,” I say when he opens his door to me.

I’d like to fall into his arms and cede all my worries to him, but he’s frowning. “Sophele, it’s a risk for you to come here. Your parents … And the neighbors …”

“I don’t care about them,” I tell him, but he doesn’t invite me in. “Where have you been?” I ask.

“Istanbul—visiting my relatives.”

“You could have told me you were going.”

“Maybe, but I wanted to keep my plans something of a secret.”

“Are your relatives all right?”

“Just fine.” He wants to tell me more—I can tell by the indecision in his eyes and then his quick look away—but at length he says, “You’d better go home. I don’t want to get you in trouble.” Since I’ve already started to cry, he says, “Sophele, please, this is hard for me, too. You may never know how hard. Forgive me.”

And just like that, he closes his door on me. I sit on his stairs because Mama will only ask me inconvenient questions if she sees me sobbing. And I stay there a long time, because I feel as if I’ve been discarded by the only man who might help me stop from turning into a Young Maiden.

That same week, Papa tells us he has been authorized to tell us about his new job. He’s become a Senior Technician in the Health Ministry’s Research and Development Department. “In the future,” he says, beaming, “we’ll be able to cure tuberculosis and other diseases with pills we synthesize in the laboratory. And we shall keep the price of these life-saving medicines down within the reach of even the poorest German.”

I try to believe that this isn’t a line he’s memorized, but I just can’t do it. And I try not to think about the other people I’d rather be with. I’ve decided that I ought to abide by my parents’ rules for a while—to make believe I’m the girl they want me to be.

Papa asks me to invite Tonio to go out with us to the Café Bauer to celebrate, and my boyfriend wears his Nazi Youth uniform for the occasion. He looks more and more like a young Cary Grant. I play with his feet under the table. He keeps pushing them away. The embarrassed son-in-law.

I eat duck dripping with a sauce of Preiselbeeren, tart little berries. It’s so good that I fake swooning and end up making even Hansi laugh. After a waiter takes away our plates, all the lights go dark and the tuxedoed maitre d’ brings a giant chocolate cake to our table topped with lighted candles. When it reaches us, I see Hansi’s name in whipped cream. My brother will be ten on the 16th of August, which is tomorrow, and we sing a rousing happy birthday. I know he wouldn’t want his big sister helping him blow out the candles in front of all these people, so I lean back in my chair, but my boyfriend helps him. Then Tonio shows me a grateful smile, and I realize he understands that I withheld my assistance out of respect for the world of men. I could kiss him for that. Being understood by him now seems lifesaving.

Over the next months, whenever I see Isaac in the courtyard or walking on the street, I slink away, but his eyes often follow me in my thoughts. A constant, watchful presence—a third eye in my head. I don’t dare to break the silence between us, however, though both of us slowly learn that it’s safe to smile at each other. That small gesture is our life raft. And what’s left of my resistance to our dictatorship.

Despite my pledge, I’ve let Georg’s murder slip away from me completely. Like so much else.

Late that summer, I realize why men like my father have been able to get more rewarding work of late; all the Jews are fired from their government jobs, including our teachers. Dr Fabig, among others, doesn’t return for the start of the new school year. According to the rumors, he turned out to be one-quarter Jewish, like his beloved Rainer Maria Rilke, and resigned before getting his letter of dismissal, although maybe a twenty-five percent Jew could have hung on to his job for a while longer.

Rini and the other Jewish girls also fail to return for the start of the new term. It’s rumored that she’s now attending an Orthodox school on Schützenstraße.

The best friendship of my life, and I allowed it to be buried along with so much else.

And so it is that my sixteenth birthday comes and goes on the 19th of September without much happiness. On top of everything else, this year’s theme for presents seems to be hideous clothing: Tonio gives me a cotton skirt in a floral pattern fit for my Bavarian grandmother; Mama buys me a plain white cotton blouse two sizes too large in order to conceal my breasts; and Papa gets me a fringed brown shawl with swastikas at its corners, perfect for a Gypsy Nazi with really bad taste, if such a person exists.

Does the girl they want me to be try on these monstrosities together, as they intend? You bet, and I even tell them that they go together splendidly.

One day in November, I spot Mrs Munchenberg while Mama and I are shopping at Wertheim’s. She must have lost her law job because she’s a saleswoman at the perfume counter. She holds a finger to her lips, then whips around so Mama won’t see her, humiliation in her bowed back.

When she dares to turn to me again, I slip away from my mother, who is busy shopping for soaps. “Any news on Raffi?” I whisper.

Mrs Munchenberg brings my hand to her cheek, then kisses it, as if I’m the confidante she’s been waiting for. “Oh, Sophie, not a thing. It’s been terrible. All we know is that he’s still in Dachau.” Her hands are frozen. “Maybe you could ask your father to write to the Justice Ministry for us … ?”

“I’m sorry, but I don’t think he’d do that.”

“Why? What risk would he run?”

“Please, Mrs Munchenberg, I have to go.”

“No, Sophie, you can’t. I need …”

I have to pry her hand off me to get back to my mother, and when I turn to check that Mrs Munchenberg is all right, she’s sitting right on the floor, her head in her hands, and another saleswoman is trying to help her up.

Tonio is relieved that Jewish physicians have been forced to leave their posts at state hospitals. Even those in private practice are prohibited from having Aryan patients.

“Imagine a Jew cutting you open,” he tells me one afternoon just before Christmas, shuddering for dramatic effect, just as we’ve reached his father’s hideout.

I say nothing, and with a sneer he tells me, “You’re always silent when I mention Jews.”

“Because I can’t think of anything nice to say about your opinions,” I reply, which makes him throw up his hands as if I’m hopeless.

For the first time ever, his penis doesn’t get hard when I lick it. The cause or the result of his sour mood? After he manages an erection, he thrusts inside me angrily. I roll over onto my belly afterward, because I feel as though he’s sliced me open. By the time I look at him again, he’s nearly dressed. I reach out to him, but he thrusts my arm away. “You know, you really disgust me,” he says contemptuously. I’m too shocked to utter a word, which gives him time to glower at me and add, “I don’t even think you’re very pretty. If you want the truth, I never did.”

He walks into the hallway and I trail after him, naked. He reaches for his coat from the hook, then grabs the door handle.

“What happened? Where are you going?” I ask, reaching behind me for a wall that’s not there; I feel as if I’ve been clubbed on the head.

“Home,” he snarls.

The door opens and closes; just like that, he has walked out on me. And I’m dumb enough not to guess how it’s possible for him to hurt me so easily. I sit on the floor, like Mrs Munchenberg, unsure of how to escape the sense of pre-ordained disaster around me. And I stay there a long time, aware of myself in that way we are when we have reached a crossroads. Each of my breaths becomes the admonishment, You thought you were safe here, but you were wrong.

After I’m dressed, I lock the apartment with the key Tonio has given me, sensing I’ve lost my power not just over my boyfriend but also over my own life.

Tonio doesn’t leave any roses or notes for me over the next week, and I don’t dare knock at his apartment or wait for him in the courtyard. Too much humiliation waits for me down that road. I’m shipwrecked on Sophie Island. A clean break is what the hundreds of miles of ocean around me are usually called, but the sands of my grief spill over into everything I see and touch. What is it that went wrong? I ache with bewilderment and grief all the time.

One afternoon during this terrible period, I have the frenzied urge to visit Georg’s apartment house. Staring up at his windows, I wonder who’s living there, and the feeling that he and I share something important makes me run away. Could it be a life that didn’t turn out anything like we wanted?

Mama asks me about my gloomy face one day while I’m cleaning the oven, but I tell her that it’s that time of the month. She sits me down and brushes my hair. We talk about Hansi. She’s sure he’ll start talking again one day soon, and then we’ll enroll him in school.

Not if we don’t get him some help, I think.

Papa suspects there’s more to my sadness than my period and tells me in a concerned voice that he’ll call Dr Nohel for an appointment the next day. He turns to leave my room, but then stops. “And where’s our Tonio been lately?”

Our Tonio … ? So my father, too, had dreams of seeing us married.

“He goes hiking every weekend with his Nazi Youth colleagues,” I reply.

“I’m sorry. That must be hard. Maybe you can start seeing him on weekday evenings. You’re old enough now. I’ll ask your mother.”

It’s not fair of Papa to show such kindness to me, because now I can’t stop the tears.

“What’s wrong?” he asks, sitting with me again.

“I’m just grateful to you.”

He wipes my eyes with his thumbs and gazes at me lovingly. “Just leave it to me. I’m sure I can get your mother’s permission.”

* * *

Sure enough, Papa wins agreement from my mother for me to see Tonio on Wednesday evenings. I let them think I’m delighted and grateful. For my first date I tell my parents that he and I will be going to the movies on the KuDamm, but instead I walk to Grenadierstraße. I hide from my life in a smoky café, under a signed photograph of Benjamin Disraeli hanging on the grimy wall. Six young men and two young women—about my age—are seated next to me, which gives me a chance to eavesdrop. They’re planning a visit to Palestine. While I sip my hot chocolate, they argue about how best to realize their dreams of a Jewish state. We watch the wooden horse carts passing by and listen to the clop-clop-clop of hooves. A pickle-seller pokes his head in, but no one’s interested. I wish I were a Jew, I think. Not a rational desire these days, but a Mediterranean sun, olive trees, donkey rides, and a warm sea would be waiting to welcome me if I were. Just the antidote to the winds of the Berlin winter. And Tonio.

And if I were a Jew, then I could see Isaac and Vera any time I wanted.

After the youthful Zionists go their separate ways, I head to the Tiergarten. The crazy jiggling of the tram sends me back to my childhood, and the shimmering, fawn-colored wood paneling feels like the surface of my grief. The landscape of Berlin rushing by—all those sooty buildings, train tracks into the provinces, and garish advertising signs for Holstina dyes, Schmeltzer’s pumpernickel, and Sonne briquettes—makes my pain more acute by that uncommonly unfair law of the human heart that twins joy with sadness.

From time to time, I used to see someone crying in public, and I’d stare at the person’s reddened, fluttering eyes without much understanding. Now, while passing the dome of St Hedwig’s Church, a fearsome-looking black-haired worker sitting near me brushes away tears, and I realize that despair has taught me I’m no different from him or anyone else. All of us hanging on by a thread.

Crying is as infectious as yawning, so I get off by the Finance Ministry on Dorotheenstraße and walk the rest of the way to the park. And I scratch myself under my panties when no one’s looking; I’ve had an itch there for the last few days and it’s getting worse. A rash? I can’t find anything but a little redness. Maybe it’s the pernicious effect of sorrow.

The last thing I want is Dr Nohel putting his hairy muzzle between my legs, so at my check-up on Friday afternoon I refrain from mentioning my itching. He prescribes luminal for my sleeplessness. When I take a first pill that evening, I learn why so many Berliners are trudging around with dull, moonlike faces. Over the next week, I feel as if I’m living inside warm molasses. I wake, trudge through the day, and pass out on my bed, still in my clothes. What people say to me eases through my head like a trail of smoke not worth following. God bless luminal; it allows me to sleep even in class.

“Sophie!” Dr Richter, our math teacher, yells in my ear one morning.

Startled awake, I have no idea where I am until he says, “Are your dreams more interesting than my lesson?”

The other students laugh. I apologize, though even Dr Richter must suspect that yes would be the right answer. Or why ask the question in the first place?

The percentage of Berliners under sedation: a statistic that never appears in the papers.

I see Tonio from afar one afternoon just before the end of the year, while Hansi and I are making our way home from a trip to Weissee Lake, where we can go skating and watch the little black ducks. There’s half a foot of snow on the ground, which means we’re both exhausted from our walk.

Tonio is standing at the entrance to our building with two boys I’ve never met, rubbing their hands together and stepping around to stay warm. New friends laughing—about girls, most likely. I stare at him from down the street. And give a small gasp when he spots me. Hansi tugs on me, wanting to run ahead to Tonio, but I jerk back on his arm.

“Don’t you move or I’ll bury you in the snow!” I tell him.

He looks up at me as if I’ve lost my mind. That’s what comes of threatening him but never really throttling him.

Tonio asks one of the boys for a cigarette and turns his back to me. I drag Hansi to Frau Koslowski’s grocery and we sit with her behind her counter. Her hunched shoulders and heart-wrenching stories about growing up poor suit me, and Hansi is happy to eat candy.

Through Frau Koslowski, I learn that I’ve just entered the club of spurned young women. Her first boyfriend was Piotr. “Tall and clever and beautiful, but ein Schwein,” she says. A pig. Sixty years have passed and she still can’t forgive him. A good role model.

When I next peer out, Tonio and his friends have gone, and Hansi and I clomp home.

Our Young Maiden troop starts a chorus in the new year, and I’ve been chosen for the soprano section. Our teacher is Fräulein Schumann. “Sadly, I’m not related to the composer,” she tells us that first afternoon. She’s slender and graceful, and no more than twenty-five. She plays a pitch pipe to start us on the right key. “Sing it!” she exclaims, and we match the sound as best we can. She says my vibrato needs training, but that I’ve got potential. She uses a lot of Italian terms: rubato, sostenuto, scherzo … She says legato is the most important thing for me to learn—to keep the notes strung together and leave no spaces between them. “No room for even the point of a needle!”

Fraülein Schumann and her lessons are my first indication there is life after Tonio.

On the first Tuesday in early January, I hear a familiar voice calling after me as I’m rushing through the chilly morning to school—Isaac. And before I’ve realized what I’m doing I’m talking once again to our local Elder of Zion.

“Sophele,” he says urgently, out of breath, since he’s run a little ways after me. “Please come to my apartment after school today.”

“I don’t think I can,” I tell him. “My father would kill me. And I’ve got choral practice.” And you owe me an apology, I’d like to add.

If he hadn’t reached out for me with his warm hand in the midst of a frigid morning, I’d have turned away. That scares me even today—how life can take an important turn at any moment.

“It’s about Vera,” he says.

Fear bursts in my chest. “Is she ill?”

“No, but she needs your help.”

Isaac greets me at his apartment late that afternoon. He gives me a bone-crunching hug, then holds my face in his hands and gives me such an adoring smile that I could almost believe that my life is only about being doted on.

“I’ve missed you, Sophele,” he says. “Please forgive me. I was very rude to you. But I was being watched by the police. I noticed the same little twit following me twice to work. An incompetent schlemiel. Though maybe he wanted me to spot him—to scare me.”

“Why do you think he was following you in the first place?”

“Who knows? Maybe it has to do with Georg’s murder. Or maybe Raffi told the Nazis something about me in Dachau.”

“He wouldn’t do that!”

“I know. . . but if he’s being beaten … Anyway,” he adds, seeing that he’s upset me, “all the excitement is over now. I haven’t seen the schlemiel in weeks.”

“I’m sorry I didn’t try coming to see you again, but my parents…” He puts his finger to my lips, then to his own. “Sssshhh … I know.”

His delight in me makes me tingle. When we’re together, it’s as if seeing myself in those radiant eyes of his is magic—as if I’ve whispered the word that makes the world sing without even knowing it.

“Have you discovered anything about who might be the traitor in The Ring?” I ask.

“Nothing. But we’ve stopped meeting … it’s just too risky. So each of us is working on his own. I’m doing what I can and so are the others.” Isaac points to his shelves, which have been emptied of at least half of their books, but before we can talk about what that has to do with his new tactics, Vera comes out of the kitchen in bare feet, her hair sopping wet, dripping all over the fraying rug.

“You are sick!” I say.

“No, I needed to wet my head or I’d have caught on fire. I’m like an overheated engine.”

“Why?”

“I’m in a panic.”

“Vera, for God’s sake,” Isaac interrupts, “dry your hair.” He points to the moat forming around her feet and then the continuing drip, drip, drip. “You’ll turn the rug moldy.”

“Isaac, it’s just an old shmata.” She spreads her legs apart and bends down like a giraffe so we can kiss cheeks.

“Mein Gott, Vera, can you ever simply do what I say?” He puts his palms together and whispers a Hebrew prayer.

“No need to call on supernatural help!” With a bow, she strides away to the bathroom.

“What’s a shmata?” I ask Isaac, who tells me it means rag.

We hear a cabinet door banging, and the sink turned on and off. Isaac rolls his eyes and begins packing tobacco into the bulb of his pipe.

“When Vera’s around you really know it,” I observe.

“She does have a certain irrepressible presence.” He’s got his lighter poised in one hand, the bowl of the pipe in the other, and he’s staring at me with happy eyes. Yet there is a certain curiosity in them that makes me uncomfortable, as if he wants my secrets.

“Do you have the jacket Vera made me?” I ask.

“Yes, it’s in my wardrobe. You want it?” He raises his eyebrows as if we’ve just hatched a plot.

After he gets his pipe going, we sneak together to his bedroom. His blankets are in a nest on the floor and dozens of old books are jumbled on the mattress.

“Do you sleep with your books?” I ask.

“Nu, doesn’t everyone?”

While I’m silently condemning the mess, he slips my jacket over my shoulders. The black silk shimmers as if it’s alive, and I’d almost forgotten the blue pockets—the color of Giotto’s frescoes. When I look in Isaac’s mirror, I reach up to the pink necklace of pearls around the collar, needing to touch their beauty.

“You look like a troubadour,” he tells me.

Vera comes in wearing a towel as a turban. She looks like an Arabian giant.

“Stunning piece of work, even if I do say so myself,” she tells me, hands on hips, tapping her foot and waiting for a compliment.

“You’re a genius,” I say, and I embrace her, and the fierce way she hugs me back makes me understand she’s been waiting for me. A woman who always needs to be reassured, though no one would ever guess.

The three of us sit in the kitchen over glasses of wine. Vera tells us that people with her overheated metabolism sometimes spontaneously combust. She read recently about a woman in Rouen flaring up and setting her couch on fire. Her husband, seeing her turn into a torch, smothered her in a blanket and saved her life, but the house burned down.

Isaac scoffs.

“I’m serious!” Vera says, lighting a cigarette.

“Then maybe you shouldn’t smoke,” I suggest.

“I said spontaneous! It happens without a fire source.” She squints at me vengefully.

“Vera, your story sounds fishy,” Isaac says.

“The article was in Marie-Claire!” she declares, as if that settles the matter.

“Oy, talk about a shmata!”

“I wouldn’t expect an alter kacker who can’t even understand French to understand.” She draws in so deeply on her cigarette that it’s a wonder she doesn’t fall over dead. It’s her sign of triumph. I stare in admiration.

“So stop sitting there like a pimple on pickle,” she tells me, “and tell us how you are. And don’t leave out any hideous details. Your misfortunes will make us feel better.”

I talk about the Young Maidens, and she and Isaac adore my stories about Our Lady of the Soufflés and Das Deutsche Mädel magazine, which Isaac refers to as Der Deutsche Madig, the Worm-Eaten German. I end up with the giggles. And as I tell more stories, I feel as if I’m made of fireworks. I’m alert for the first time in weeks. Then I drink some tea to dilute the wine that Isaac says is setting off too many sparks in my head.

“So when are you going to be on the cover of the Worm-Eaten German?” he asks me.

“I’d have to do something special to merit that.”

“Maybe you could drown an old rabbi,” Vera suggests.

“Vera, Sophele has no choice,” Isaac notes.

“Is that true?” she asks me, unraveling her towel and shaking her clumped hair down to her shoulders.

“My mother would boil me with her potatoes if I quit. Anyway,” I chirp, trying to make the best of it, “what we do isn’t always idiotic.”

Vera gazes down at me skeptically, her eyebrows lifting under the awning of her forehead. Not a good look for her. I want to find something positive to say about the Young Maidens, so I talk about Fräulein Schumann and our chorus.

“Learning how to sing is like being able to do something I never thought I could,” I tell them.

“Like a blessing,” Isaac says.

“Exactly.”

“Has Hansi resumed talking?” he asks.

“No, not a word.”

“And have your parents found a school for him?”

“No, he’s home all the time. They’re … they’re embarrassed by him now.”

Vera snorts. “Soon they’ll lock him in a wardrobe!”

“You’re not getting along very well with your Mama and Papa, are you?” Isaac asks.

“No, but things have been better since I joined the Young Maidens and … and started to pretend I’m a good daughter.” To defend them, I add, “I just think they’re caught up in things beyond their control and don’t know what to do.”

“Good try, Sophele,” Vera says, “but Hansi is not beyond their control. Helping him lead his life is, in fact, their responsibility.”

She lets me get away with nothing. I love her for that, though she doesn’t also have to give me such a look of outrage.

“I need my notebook,” Isaac says, and he goes off to his bedroom.

I ask Vera for a cigarette and try to copy her style of smoking. Isaac returns and writes a name and phone number on a sheet of paper, then tears it off for me. “Tell your father to call this man, Philip Hassgall. He studied with Rudolf Steiner, the Austrian philosopher and educator. Philip sometimes brings kids like Hansi back to us. Not all the way, but they are able to lead independent lives.” Anticipating my question, he adds, “He’s an Aryan, so you don’t have to worry.”

“Where will I say I got his name?”

“In an article in the newspaper. There was one a few months back. I can get a copy of it if you need it.” He pours more tea into my cup. “Are you sketching your brother?”

“Sometimes.”

“Good. That’s important for both of you. Wherever he’s gone, he must always know you are there for him.” He sips his wine and gives me an inviting smile meant to get me talking again, but I don’t make a peep. “What’s wrong?” he asks.

“I’ve mostly stopped drawing. I only draw Hansi … and only infrequently.”

“Why?”

“Frau Mittelmann left for France and …”

That’s when the news of my break-up with Tonio tumbles out of me. Complete with sniffles, tears, and even a nosebleed because I blow too hard into Isaac’s handkerchief.

Vera leans forward and catches my blood on her fingertips to prevent my troubadour jacket from getting stained. “Men!” she snarls, as if that’s all one needs to say on the subject. She’s holding Isaac’s handkerchief to my nose. A cigarette dangles from her lips, and the curling smoke forces her to shut one eye. “Tilt further back or it’ll never stop.”

“If I tilt any further my neck will snap off!”

“Are you still in love with him?” Isaac asks.

“I think so,” I reply in my muffled voice.

“Then you might as well just keep bleeding,” Vera declares, yanking the handkerchief away.

“Vera!”

“Okay, okay …” She starts blotting again.

“Sophele, try talking to him about what’s bothering you about your parents and the way our country is going,” Isaac tells me. “He could be waiting for you to be honest with him. He’s caught up in things beyond his control, too.”

Vera makes a skeptical tsk noise. “Oh, please, Tonio is what … sixteen, seventeen?”

“Seventeen,” I tell her.

“At that age, no one respects anyone else’s opinions. I didn’t. And I’m quite sure you didn’t either, Isaac.”

“I respect Tonio’s opinion—at least sometimes,” I point out.

My nose has stopped bleeding. Vera leans away from me and says, “You respect what the little delinquent says because you’ve got a soufflé that can be bruised, meine Liebe. And because his affection seems more important than being right or wrong. That errant belief is what has always doomed us.” She shakes her head as if all women are a lost cause. One of the many themes to Vera’s life.

“Anyway, I can’t go to him,” I announce. “He has to come to me.”

“Take him a present as an excuse for visiting him,” Isaac says excitedly. “How about a drawing of Hansi.” Seeing my frown, he says, “Or a book—one of mine. I’m getting rid of them anyway.”

“You’re not throwing them out?”

“Good God, no! But when there’s a war on, books are some of the first casualties, so I’m sending them away. It’s part of a new campaign I’ve just started in this war.”

“Is there a war on?”

Vera points a make-believe pistol right between my eyes. “You’re the enemy … you and me and Isaac.” She pulls the trigger and makes a popping sound.

“And Hansi too,” Isaac adds gravely.

I feel as if I’m backed up against a wall made of my own fear. I have to fight too, I think, fiddling with the pearls on my collar. “So where are you sending your books?” I ask.

“To my relatives in Turkey. I’m keeping only the ones I need for my studies.”

“Oy!” Vera says, snorting. “You’re not still trying to wriggle your way into Araboth?”

“How else will I beat Sophele to the cover of Worm-Eaten German magazine?”

“Is that why you went to Istanbul?” I ask. “To prepare your relatives to receive your books.”

“No, not really. I went because we’ve decided to take the war overseas.”

“I don’t understand.”

“We were going around to the embassies, as you know. But we weren’t getting very far, so I had another idea,” he says excitedly, his hands pushed boyishly between his legs. Why not start working with journalists in Paris and London, Rome and Budapest? Why not convince them to write about what the Nazis have in store for the world—long, intelligent articles. So I went to Istanbul to present our cause to some reporters there. A few good pieces have already been published. The plan is to build up popular feeling against the Nazis and then, when the time is right, start planting the idea in people’s heads for an embargo. While I was in Istanbul, others in The Ring went elsewhere. We’re going to work individually from now on. As I told you, no more meetings. It’s too dangerous now that the Nazis have so much power. So each person has a country. And we’ve agreed not to talk about the progress we’re making. Even if our telephones are tapped, the Nazis won’t learn anything.”

“But if they do find out, they’ll say you’re committing treason! You could be executed.”

“I am committing treason—at least from their point of view!” Sticking his pipe stem in his mouth and grinning, he adds, “And I’ve never felt better.”

“Isaac,” I say, looking down to prepare for a confession that may irritate him, “back in early June I followed Julia … to Karl’s Cellar.”

“Big surprise!” he exclaims, scoffing. Then, with merriment in his eyes, he says, “I’m the one who sent Karl to chase you out.”

“How did you spot me?”

“It was K-H,” Vera says. He notices every girl between the age of sixteen and thirty within half a mile. He’s got a kind of lecherous radar.”

“You drew lots out of a hat,” I say.

“For those of us without language skills or preferences, we decided country assignments that way.”

“I had to go to Madrid,” Vera says glumly.

“It didn’t work out?” I ask.

“Sophele, I can assure you that being jeered at in Spanish is even worse than in German. The street kids … malignant little pests … and with a satanic ability to spot me even in the dark. As for the journalists, they’re doing an excellent job on Hitler, but Spain has its own problems. There might be a civil war.”

Checking Vera’s watch for the time, I jump up in horror. “Yipes! I’ve got to get going.”

“But I haven’t even asked you my question,” she whines.

“I’m listening.”

“Sit down first.”

After I’m seated, she announces, “I’ve found someone who wants to be the father of my baby.” She makes a grimace as if I might condemn her.

“That’s wonderful!” I exclaim, though I won’t deny thinking she might give birth to the mieskeit of the century. “Who’s the lucky man?”

“A Polish mason. Very handsome. And get this … he’s seen a photograph of me and my face didn’t dissuade him. K-H found him for me while photographing a construction site.” She looks up to the sky and mouths, Thank you, Jesus, Mary, and Karl-Heinz Rosenman … “The point is, I’m meeting him in two days to discuss when we’ll start to … to … you know …” Vera tilts her head to the side and gives me a girlish smile.

“It’s incredible, you haven’t even met the Rudolph Valentino of Poznan yet and you’re already turning into a blushing bride!” Isaac observes. Pointing his pipe at me, he adds, “What she means is, she has to talk to him about when they’ll start schtuping.”

“Fucking,” Vera translates, a furrow in her brow, concerned, perhaps, about how she’ll perform after so many years of hiding backstage. “And I can’t be alone when I meet him, Sophele. I’ll burst into flame and set what’s left of the Reichstag and the rest of Berlin on fire. So I want you to come with me.”

Before I leave, Isaac gives me a monograph on the German painter Caspar David Friedrich for Tonio, though I know I’ll never address so much as a single word to him unless he apologizes to me first. Childish or wise, I know it with the certainty of the small death in my gut.

The following Thursday morning, I tell my mother we’re having a special Young Maidens supper and meet Vera at her apartment on Blumenstraße in the late afternoon. It’s a top-floor garret in a soot-darkened building with a mildewed wooden staircase that creaks under my feet as if it’s been practicing for a film set in a haunted house. On her door she’s tacked a photograph of Minnie bleeding onto the street. At the bottom she has written, “If you approve, vote for Hitler.”

After I knock, she peers at me through a slowly opening crack, then pulls me in as if I’ve arrived late. “I don’t like my neighbors knowing who comes and goes,” she explains.

Her living room is a tobacco-scented hothouse crammed with rickety bookshelves, a small round dining table—wooden with a metal rim, of the kind used in outdoor cafés—and two old chairs that she’s upholstered with black and white striped fabric.

“My place is gemütlich, cozy, isn’t it?” she says cheerfully.

“Absolutely,” I enthuse, though suffocatingly cramped would better describe it. Worst of all, the ceiling is badly cracked and sags down half a foot, as if it’s filled with rainwater. She reaches up and palms a big fissure. “I can hold it up in an emergency, so don’t worry.”

“Who’s worried?” I say, practicing my acting skills. “Can I see the rest of the apartment?” I want to find the bathroom in case I have the courage to ask her my favor.

“For an Aryan you’re pretty nosey, aren’t you?”

“If I’m going to inform on you, I need to case the joint.”

Her bedroom is just big enough for her cot, which is so long that it looks like a barge. “My mattress was special-ordered from Heitinger’s,” she tells me. “Isaac got me a discount.”

Black curtains frame two small windows. For the first time I realize that Vera is poor.

“Is Isaac’s business doing all right?” I ask her.

“It was going well until a few months ago when he started losing his Aryan customers.” She feigns polishing a crystal ball and gazing into its depths. “I see hard times ahead for Isaac Zarco and his friends, including … what’s this? I see a girl … a very pretty but evil girl with a gorgeous, pearl-collared jacket …”

“You never cease to amaze me,” I tell her, laughing.

“Amazing is my only option,” she replies, grinning.

“Not true,” I tell her. “I don’t know what I’d do without you and Isaac.”

Vera caresses a hand through my hair, plainly touched, then gives me a tour. The bathroom is covered in mildewed brown tile, and two red-tinted bulbs stick out like clown noses above the mirror. It’ll have to do, I think. “I need your help before we go find Prince Charming,” I tell her.

“With what?”

“I have an itch that won’t go away. Down below,” I say, pointing. “But I can’t find anything. Would you take a look?”

She closes the shutters and goes to her bedroom for a reading lamp and chair. After I take off my skirt and slip, she has me sit on the bathtub rim. Pulling up her chair, she shines the lamp between my legs. It’s hot. “Hmmnnn,” she says darkly, peering at my personal parts.

“Please say it’s nothing serious!” I plead.

“Sophele, I’m afraid you’ve got Filzläuse.”

In German, that means felt-lice, and I’ve never heard of them before. “What are you talking about?” I ask skeptically.

“Filzläuse, my dear—you’re crawling with them.” Vera stands up with a grunt and explains the miniature parasitic nature of crab lice to me. To show me how they’re biting into my tender skin, she opens her mouth and bares her teeth—nicotine-stained daggers.

“How many do I have?” I’m expecting she’ll say ten, or at the most twenty. I am, at the time, a total idiot.

“I don’t know, maybe a thousand!”

“Oh, my God!”

A chill shoots up through my body and out the very top of my head. A rocket of dread. The next thing I see is Vera leaning dangerously close to me. For some reason, the ceiling is behind her. She’s holding her hand to my forehead, and when I reach up to brush her cheek to make sure she’s real, she says, “Welcome back to planet Earth.”

She has me sit up and drink a cup of linden tea, everyone’s favorite remedy. “You passed out for a few seconds,” she tells me. “You’ll be fine now.”

We put on my slip and skirt. I cradle the teacup in both my hands like a tiny girl. My arms feel as weak and pliant as a rag doll’s.

“How long have you let this go on?” she questions, washing her hands at the sink.

“A couple of weeks. Vera, where did they come from?”

“Take a guess,” she replies, grinning like a rogue.

“I’ve been in some pretty run-down movie theaters. And the bathrooms there …”

“What in God’s name do those Young Maidens teach you?” she hollers, scandalized.

“Oh, Vera, tell me how I got them,” I moan. “I’m not in the mood for guessing games.”

She dries her hands with a dishtowel. “They’re a parting gift from Tonio. The only way you can get crab lice is from someone you’ve slept with.”

“Oy,” I say.

“Oy is right.”

“Which means …”

I decide not to end that troubling sentence, but Vera does: “… that he must have slept with a girl who was infested.”

Now I know how he could leave me so easily! He’s found someone else. Or a great many someone elses.

We purchase dusting powder for my lice and I sprinkle it on myself in the bathroom of Karl’s Cellar, creating toxic puffs in the air that sting my eyes. I then rub the insecticide around per Vera’s instructions, furious at myself for being such an innocent. After I wash my hands raw to get off the stink of powder, I slip back into the restaurant, picturing the busy city of lice feeding off me. My own Metropolis right between my legs.

Vera waiting nervously for the Polish Rudolph Valentino

Vera is sipping ouzo—her preferred drink—when I join her. Looking around, I discover the restaurant is filled today with women’s shoe salesmen, as my mother would say, some of whom are holding hands and even kissing.

“Are there lots of places in Berlin for men who like other men?” I whisper to Vera.

“Dozens,” she says. “And thank God for that or where would I be able to go?”

Our Polish worker enters after ten minutes. Even in the dim, moist lighting of this red-tinted fish tank, he’s gorgeous, though he’s more of a middle-aged Randolph Scott than Rudolph Valentino. His thick gray hair is pleasantly mussed, and deep, masculine wrinkles frame his blue-gray eyes. His walk is solid, too, and has a bit of a lilt to it, as though a jig—or more likely, a polka—is playing in his head. I have a vision of him as a rough-talking cowboy in an American Western.

“Oh, my God!” Vera whispers to me, her megalithic jaw dropping open. “Get a look at him! My baby will be gorgeous.”

Fearing he’ll walk out without noticing us at the back, she waves to him, arms high, as though she’s a semaphore specialist helping a battleship into berth. He rushes to us purposefully and shakes her hand and mine in his work-toughened paw, then drops down next to her with the sigh of a heavy laborer and gives us a sweet and eminently seductive smile. His nails are crescented with dirt and his fingers are enormous—as big as cigars.

As we converse, I notice that whenever he really gets a good look at Vera, his eyes tear. Cristophe, the sensitive cowboy from Poznan!

After the introductions and a few pleasantries about the wretched weather, a popular subject of conversation for Berliners at least ten months a year, Vera asks how he likes living here, but his German is no more than rudimentary. “Very big,” he says, opening his arms wide. Then he puts his hands over his ears. “And too much noise.”

He lights her cigarette, then one for me and finally himself. The touch of his hand makes either my lice or my soufflé itch, though I’m pretty sure I know which.

Vera and Cristophe talk in ever-tightening circles around the subject at hand and finally agree to begin meeting at her apartment in two weeks. She hands him a first payment in an envelope and tells him her address is inside. Then she squeezes his arm. “God bless you, Cristophe,” she says as if he’s saved her life, then races off to the woman’s room because she hasn’t drunk enough ouzo yet to numb her emotions.

Instead of going directly home, I head to Georg’s apartment after saying good-bye to Vera, and I knock again on Mr Habbaki’s door; I’ve thought of some questions I should have asked him the first time around.

My tiny Lebanese host serves me almond cookies and cherry juice, overjoyed to have a visitor, and after he’s vented his irritation about his apartment’s faulty heating, we get down to business. Unfortunately, he doesn’t recall much of anything about Georg’s last weeks.

“Was he sick before he was killed?” I ask, thinking he might have been poisoned slowly.

“I don’t think so.”

“Did he get any unusual guests … other than the people who moved his furniture? Did he complain of being followed or watched? Did he change the time he left his apartment in the morning?”

Mr Habbaki can’t recall anything.

He soon runs out of cookies and I run out of questions. Fortunately, a retired nurse who lives upstairs and who was out the first time I visited remembers more. Mrs Brill and I sit on her black velvet sofa together. After I’ve complimented her on the beige bedspread she’s just crocheted for her son, and the white ceramic water dish she purchased yesterday for her cross-eyed toy poodle, Max—named by her late husband after the German boxer, Max Schmelling—I interrupt her rambling and ask about Georg. Max sits on her lap, pants, and licks his scrotum and paws as we talk. After about ten minutes, she finally says something worth my while. “I do remember one unusual thing,” she says, placing her hand in mine, as if we’ve known each other for ages, “because Georg had such beautiful hair. I saw him one day in the street, just before … before he died, and all of it was cut off.” She makes a slicing motion to emphasize her point. “I told him, it’s such a shame that you’ve cut off all your beautiful hair. And do you know what he told me … ?” I give a big nod, since she’s slightly deaf and maybe a bit batty too, and she says, “‘It’s my new look for the spring, Mrs Brill.’”

Did Georg want to appear less recognizable to his enemies? Maybe he found a new job that required short hair—one that he told no one about, not even Vera.

“Georg was always changing the way he looked,” Isaac tells me dismissively when I inform him about the haircut. “He didn’t like being … being trapped by other people’s expectations.”

“So you don’t think he’d taken a new job that he told no one about?”

“Definitely not. We spoke nearly every day on the phone and he’d have at least given me his new number.”

On my insistence, Isaac fetches K-H’s photographs of the dead man, and as he hovers over me, I confirm that Georg’s hair was closely cropped. And a bit ragged around his ears. I’d missed that before, having concentrated solely on the swastikas.

“If you ask me, he got a bad haircut,” I tell Isaac, who shrugs as if it’s of no interest.

He lets me keep the photos on the condition that I never mention them to anyone, and I slip them in behind Garbo in my K-H Collection.

Over the next few mornings, before anyone else is up, I take them down and study them under the hot circle of light made by my reading lamp. Once, Hansi wakes up and joins me, leaning against my back and pressing his snoozy face over my shoulder. I flip them over right away, but then—figuring Hansi can’t do any harm—show them to him and tell him that they’re puzzle pieces that don’t quite fit. I’m hoping that he’ll spot something that’s invisible to me, but after a half-hearted look, he just yawns and goes back to bed.

I follow Julia twice more over the next week, but she never deviates from her usual routine. One woman’s simple, contented life is another’s dead end.

At the end of January, on the appointed day and hour for Vera’s rendezvous with Cristophe, an envelope is slid under her door; she rips it open to find a two-word note: “I’m sorry.”

“No further explanation,” she tells me when we meet at Karl’s Cellar later that week. “I guess that once he got a good look at me in the flesh, he decided …” Her voice breaks and she covers her head with her cloak. A leper whose last hopes have been dashed.

As we sit together, I realize that the only answer is for the prospective father not to get a look at her face or body, which means she’ll have to wear a mask. Or he’ll have to be …

“Roman Bensaude!” I whisper to her excitedly, but Vera won’t come out of her mohair hiding place to hear my new idea, so I tug it off her. “I bet Roman would have a baby with you,” I tell her. “I don’t know why I didn’t think of him before.”

“He’s blind as the Bodenschicht of hell—the bottom layer of hell.”

“Exactly. He won’t see you. It’ll be perfect.”

“Sophie, my child could be born blind! And deformed! Why are you trying to make me feel worse? Does seeing me distraught give you some sort of perverse pleasure?”

“Look, I thought you were willing to take risks. And you’re fond of Roman, right? Be an optimist for a change.”

“Optimism is a word without meaning for me.”

I quote her one of Isaac’s jokes: “What’s the difference between an optimist, a pessimist, and a kabbalist?”

“I don’t want to know,” she groans.

“An optimist sees a fly and thinks it might be an eagle, a pessimist sees an eagle and thinks it’s probably just a fly, and a kabbalist sees an eagle and a fly and thinks they’re both aspects of God!”

She gives me a dirty look.

“Sorry,” I tell her. “All I mean is that with Roman as the father, your child will be talented and handsome. And I’d bet he’ll be a very good father.”

“Roman is a Jew!” she growls.

“So much the better. You’d make one more enemy for the Nazis in your womb.” I risk taking her tulip bulb chin in my hand and say, “It’s a war, remember?”