![]()

Tonio comes to the funeral in uniform. We link hands with Hansi between us, and later he speaks to my father alone. I can guess what they talk about, because when my boyfriend catches up with me, he brings up marriage for the first time, but I do not want to be tied to him or Isaac or anyone else. Still, he obliges me to talk of our future, and as we do, I decide I want black borders to grow around my life, the ones Mama should have had. I want to be a girl in a Rouault painting.

“I can’t talk about anything right now and know what I’m saying,” I finally tell Tonio. “We’ll talk again in a couple of months.”

“Maybe your hair will have grown back by then,” he says, trying to cheer me up.

“I hope not,” I warn him.

While the minister’s sermon drags across our emotions, Hansi sits right on the lawn, his legs crossed. I can tell the boy fears rain. Papa looks at him as if he’s a lost cause, his face compressed by anger. I’d like to punch him for forgetting how to love my brother at the worst possible time.

After exchanging whispers with my father, Aunt Ilse marches over to Hansi and informs him that he’s a ridiculous sight. She grabs his wrists and tries to tug him to his feet, whispering that he’d better not fight her, which makes him shriek like a cornered animal, so I rush to her and say, “If you don’t leave my brother alone, I’ll break your neck!” Ich breche dir den Hals! I use those exact words, and even now I can feel the drum-tautness of righteousness in my heart. Aunt Ilse, ready to burst into tears, lets go of Hansi and orders me never to talk to her like that again, but I don’t apologize. I take Hansi’s hand and ask him to step back with me from the grave, which he does. Later, I overhear Ilse informing Grandma that I may already be suffering from the family madness.

What family madness? This is news to me. And good news, too, since maybe my aunts will keep away from me forever.

The life I imagined for myself slides away from me after that, as if it’s a message carried out to sea. I do our food shopping and cook every night, and I quit the Young Maidens without attending a final choir practice. Fräulein Schumann never calls, which surprises me.

Now, so many years later, I’m astonished that I didn’t resent having to make this sacrifice. Without being aware of it, I must have spent those months after Mama’s death in a state of dissipated shock, doing my best to simply keep walking.

Papa seems to react to Mama’s death much like a Rilke poem, slowly, subtly, and also in surprising ways, though he would dismiss my comparison to verse with a derisive snort. He takes a week off after the funeral and goes around the house quietly, as if walking on tiptoe. He closes his eyes all the time, and sometimes his lashes squeeze out tears, which makes me sit with him and rub the back of his hand as if I’m polishing our grief. He takes his time when he eats supper but says little to us, as though he’s a condemned man living out his sentence. He’s aged, too—I’m aware now that the hair on his temples and over his ears has grayed. He helps me wash the dishes, mostly so we can talk about my studies, which have not gone well since Mama’s illness began. He’s worried I may fail all my classes, but for better or worse, I’ll do what I have to do to pass.

He’s good with Hansi, too, and does jigsaw puzzles with the boy even first thing in the morning. We don’t talk about Mama. I don’t bring her up because I sense that whatever I might say would only make him feel worse, and he must be thinking the same about me.

Papa becomes the man he was for a time, but when he goes back to work, his sudden absence is like a second death to me. I know it’s unfair, but I want him waiting for me when I get home from classes, and Hansi does too. For a time, the boy goes on strike the only way he knows how, by refusing to go to school. Papa pleads with him and, when that has no effect, yells at him so cruelly—calling him an embarrassment to his face for the first time—that Hansi bursts into tears and starts scraping at his neck with his fingernails. Is his frenzied swiping a symptom of his realization that the red-faced bully screaming at him is all he’s got left? Dr Hassgall comes over the next morning. God knows what magic powder that man keeps in the pockets of his tweed coat, but Hansi goes back to school with him.

As for Tonio, he’s particularly good with Hansi during our period of grief. When he’s on leave, the three of us go for long walks down by the Spree. We bring stale bread along so we can feed the ducks and geese.

Over the next few months, Papa distances himself progressively from Hansi and me. When he doesn’t think I’m watching, he looks at the boy as if he’s an intruder, and he flees to his bedroom after supper. Our father never sits with us to read his newspaper or listen to the radio. I want to be alone … Garbo’s famous line, but now it could be Papa’s. Could he be sobbing into one of Mama’s blouses, breathing in the lost scent of her like I sometimes do?

Only now do I realize that Mama—and not my father—was the center of our family.

Then the next phase of his flight from us begins: Papa leaves for work every day before Hansi and I are awake. Maybe we’re too painful a reminder of our mother. Or maybe he knows he needs to earn a living for our family and has to get on with his life despite his grief. That doesn’t occur to me at the time, but it seems an obvious explanation now.

At times, he becomes affectionate again and takes us out to supper. Afterward, he buys Hansi all the chocolate ice cream he can eat. Isaac says that I need to give Papa time. “The death of a wife is a road that has no end.”

True for the death of a mother, too: I cry tears enough to fill the giant hole inside me, but it never gets filled.

Gurka and her milkmaid friends whisper and snicker about how boyish I look whenever I pass. Their amused stares open old wounds, but I’ve already left school behind in my mind. I take one or two mornings off each week after Mama dies and discover that life is much easier when I have half the day free.

When I tell Isaac I’m quitting, he takes out his wallet and replies, “I’ve been expecting this. I know all rational arguments will fail with you, so I’ll pay you to stay in school.”

“How much?” I ask, laughing.

“However much it takes.” He spreads out a fan of Reichsmark.

“I don’t want money, I want affection.”

“Deal!” he says, opening his arms.

So it is I am bribed back into those dreadful classrooms, with curses against the Jews carved into the desks and “Heil Hitlers” in our teachers’ greetings, and exams on racial characteristics. What I remember most from my second- to-last year is our German professor, Dr Hefter, informing us in a proud voice that German is superior to English and French because even Negroes can speak those other languages. It’s then—for the first time in ages—that I raise my hand to speak.

“Yes, Sophie?” Dr Hefter asks, astonished that I want to participate. Such an innocent smile he has. It’s almost a shame to betray his pleasure in inviting me to talk.

“Seeing as how Dr Goebbels can speak German reasonably well,” I tell him, “I think we can put aside your argument that it’s a language for superior men.”

Hushed, pressure-filled silence fills the classroom around me and Dr Hefter jerks his head back as if I’ve whacked him. In his poodle-brown eyes, I can see his tiny mind racing around in circles, trying to find an explanation for this dangerous effrontery. Seizing the only one his faulty nose can sniff out, he grins. “Sophie has made a joke, but I must tell you, young lady, that …”

“It’s no joke,” I interrupt. “Anyone with eyes can see that Dr Goebbels is of inferior breeding, and yet he can speak German with reasonable accuracy. Does he speak even broken English or French? I doubt it. If he did, then he wouldn’t be a minister in this government because he’d be too cultured for the National Socialists.”

Dr Hefter coughs to cover his discomfort, then goes to his desk, and picks up the play by Schiller we’re to begin today: William Tell. “Please open to page one,” he tells the class.

And we do open our books. And no one ever says another word about my blasphemy, though Dr Hildebrandt, our headmaster, gives me a stern lecture on proper behavior the next morning. He ends by slapping his metal ruler into his desk so loud that I jump.

“Consider yourself just a single infraction from expulsion, young lady!”

That I manage to get through the school year without being expelled is a testament to my patience, though it is not often a quality I associate with my younger self. And it is good to have the summer free—for my Jewish studies with Isaac and long walks in Berlin’s parks with Tonio and Hansi. But these months of graceful ease end all too soon. Just after the start of my final year, on the 15th of September, our government passes two new laws designed to keep the vermin off the main deck of the refurbished ship we’re sailing on. The “Reich Citizenship Law” strips Jews of their German nationality and their right to vote, as well as to hold public office; and my favorite, the Teutonically pompous “Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor,” forbids Jews from marrying “Germans” or even having sexual relations with one.

These enactments will be remembered in years to come as the Nuremberg Laws. But whatever their name, Isaac and I are now outlaws. And abracadabra … he is stateless. Our orgasms have now become evidence proving our guilt, and we risk either imprisonment or hard labor, according to the new law.

“I don’t know about you, but I’d prefer hard labor, since I’m already used to that,” I tell Isaac, laughing. I’ve just raced up to his apartment, and I’m giddy with the news that I’ll be fighting on the front lines every time we dive under his down comforter.

“It’s not the least bit funny,” he replies, annoyed, pouring me a cup of coffee since he says I need sobering up. “The Nazis want to change our instincts about what is natural.”

“But no one, not even the most ignorant peasant in the Black Forest, could really believe that you can change who is a German from one moment to the next. Declaring that you’re not a citizen is like declaring that an oak tree isn’t a tree. My God, you’ve been in the army—you’re more German than my father!”

“Sophele, you want our people to behave rationally, but they never have and never will. And this is a very bad sign.” He shakes his head morosely.

“A sign of what?”

“In 1449, the Spanish monarchy passed laws that stated that the Jews had tainted blood. As a consequence, we became defined not by our religion, but by our impure nature. Converting a Jew to Christianity would not take away that impurity, because our religion meant nothing. It was only our blood that counted. So the only way to prevent us from infecting those with Spanish blood was to kill us, and the Inquisition set up by the Church did just that! Then the Portuguese copied them. For hundreds of years they hunted us down. You see? The Church would have tortured and killed Berekiah Zarco and the rest of my ancestors if they hadn’t escaped to Istanbul.” He ends his sentence on a sharp intake of breath and doesn’t continue.

“What is it?” I ask

“I think that Berekiah has been trying to tell me that the killing is about to return, and that this time it will be worse, but I didn’t want to believe it.” He gives me a penetrating look.

“Sophele, these laws are a prerequisite to legislating murder.”

I think Isaac is wrong to be so worried until the next day at school. Dr Habermann, our philosophy teacher, has written the new rules about who is a Jew on the board, from which I learn that a Jew is anyone with at least three grandparents who are Jewish, or anyone who has two Jewish grandparents if he or she was a member of the Jewish religious community when the new law was passed, or joined the community later, or was married to a Jewish person, or … I don’t read to the end, because all these clauses are absurd; we are all aware that a Jew is anyone who practices Judaism, just as we know that Jews have been German citizens for as long as there has been a Germany, but all the other students copy down every convoluted word in their notebooks as if they’re sleepwalking through life. And so it is that we come to accept that an oak tree is no longer a tree. And if Hitler decides tomorrow that gravity no longer exists, will we fly up into the air?

On his next weekend off, Tonio agrees with me that these laws are absurd, but he says that Hitler’s genius is in knowing that a nation’s dreams don’t always make sense. “It’s simple,” he tells me in his preacherly voice when I tell him I don’t have a clue what he’s talking about. “Germans have always dreamed of having their own country, free of … of impurities and foreign imperfections. And the Führer has taught us that we have every right to live out that dream.”

We’re lying together in bed when he declares this, and I roll over onto my belly so that I don’t have to see his self-assured face asking for my agreement. And because I’m remembering Vera telling me—when I first met her—that it’s better that dreams remain in their own realm. If only Tonio weren’t so pleased about Hitler’s malignancy, our relations would be easier. Though I’m beginning to see that he could be useful to me in terms of knowing what the Volk are thinking. After all, it will be important to know when it has become too dangerous for Isaac and Vera to remain in Germany.

As a result of the Nuremberg Laws, two of Isaac’s oldest Christian clients refuse to do business with him any longer or even to pay their outstanding bills. Isaac tries to meet with them, but humiliation is the result; they refuse to even let him in their offices. Is this a turning point in his way of thinking? Instead of spending extra hours drumming up new business, he buries himself in Berekiah Zarco’s manuscripts more obsessively than ever. When I ask if there’s anything I can do to help with his business, he replies matter-of-factly, “Don’t worry, the factory is healthy enough to take care of itself,” then asks me to make him some coffee so he can concentrate better.

One cold evening in late November 1935, Papa takes us out to supper at the indoor restaurant of the Köln Beer Garden, and a woman in a fur coat the size of a brown bear joins us there. She’s twenty-seven. I know, because I ask. She talks sweetly to me, and she is full of sincere and sad glances at Hansi. She wears bright red lipstick and cobalt blue mascara, which makes her look like a mutant parrot. Her low-cut black dress is elegant and a bit slutty, like an outfit a gangster would choose for his girlfriend. Her earrings are gigantic pink pearls. Her name is Greta Pach, and Papa introduces her to Hansi and me as a secretary at the Health Ministry.

“Your father’s secretary,” Greta adds, staking her claim, and Papa gives her a quick-tempered glare.

That single glance from my father gives their game away before it’s even started. And when I ask Greta how long she’s been at the ministry, she replies in a breathy voice—proto–Marilyn Monroe—that she started nearly four years ago, which means she was on the job the day Papa arrived.

Hansi doesn’t do the math, which is just as well, but I know now that she and Papa have been working together—and probably sleeping together—since the moment he joined the Health Ministry in August 1933. Two years, four months ago.

I go to the bathroom since I don’t want to break down in front of Papa. Will he leave us now, so he can start making little red and blue parakeets in Greta’s womb? I splash my face and neck with cold water, but I’m burning up. Sitting in a stall, I realize I have a decision to make: I can either make a scene and risk losing Papa, or I can act as sweet as possible so that he’ll stay with us.

As soon as I see Hansi slurping his soup, I realize I really have no options. I’ll be nice to our father for maybe the same reason Mama was. He Who Earns the Money Holds All the Cards. That’s what I’d like to engrave now on Mama’s gravestone.

“I’m glad you could join us for dinner,” I tell Greta after I sit down, and I ask where she lives, doing my best to sound cheerful.

Papa, believing I’m up to no good, tells me I’m being far too inquisitive, but she waves him away and says, “No, Sophie has a right to know about me,” and I can see from the cheeky, amused way she looks at me that she knows that I know what’s up. She says she lives in “too large” an apartment in Charlottenburg. To my subsequent questions she tells me that she divorced her stockbroker husband four years ago. Her maiden name was Allers. She adds that she loves painting, particularly Cézanne’s landscapes. Is that indicative of good taste or did Papa tell her what she’d need to say to win me over?

Papa’s hand rests like an awning over his irritated eyes during our friendly exchange as if he’d like to drop through a hole in the floor. From the way he’s fingering the salt shaker I can tell he’s dying for a cigarette. I understand now that this dinner was Greta’s idea.

“Someday when you come over, I’ll be happy to draw you,” I tell Greta. And I will indeed be gratified; I’ll give her a beak and feathers, and I’ll add a big cheetah behind her, with my own saber-toothed smile, ready to swallow her whole and spit out her goddamned pearl earrings.

“And you’ll have to come to my apartment,” she gushes. “You and Hansi both. You’ll love my new curtains! They’re blue and green brocade.”

“I’m a real big fan of brocade,” I reply.

She doesn’t recognize my sarcasm but Papa gives me a look of warning. Though he’s the one who’s going to have to watch it, because I understand now why we never had enough money to buy a bigger apartment; keeping Greta warmed by a brown bear and getting her new drapes has sentenced Mama, Hansi, and me to a smaller life. Still, I compliment her dress, which makes Papa nod at me as if to say, That’s more like it!

Does he suspect I’d like to tip over the tall white candle at the center of our table and set his pinstriped suit on fire?

After dessert, he lights Greta’s cigarette and takes one for himself from her tin—Haus Bergmann, his own brand. I ask her for one, too, which she offers me with a pleased smile, but Papa is quick to add in an outraged voice, “Sophie, I didn’t know you smoked. And I don’t think it’s a good idea.”

“You don’t know a lot of things,” I say. “So just give me a light.”

He frowns nastily, so I give him a look of warning, though my nervousness is like a fist around my throat, and I don’t know where this crazy courage to defy him comes from, and hope Mama won’t hate me if I don’t have the will to fight him for long.

When I tell Isaac about Papa’s affair, he says, “You’d best be very careful with him. If he’s fallen in love, he won’t have much patience for anyone who tries to get in the way.”

Tonio tells me much the same thing: “Just let your father and Greta get on with their lives.”

Their advice infuriates me. And seems indicative of a secret worldwide conspiracy of men.

I search in vain through my father’s coat and pants for his key to Greta’s apartment over the next couple of weeks, and while seated bent-backed on his bed, I realize Mama also must have done a lot of searching over the last two years—for lipstick stains, hotel receipts, and God knows what else. Or maybe her torment began much earlier; she must have suspected—like I do—that this wasn’t Papa’s first affair. If only she’d had the courage to confide in me. Then, all our interactions—even the difficult ones—might have been based on trust, and everything I feel now might be so much less weighted with a sense of having missed out on our life together.

Maybe my mother even met some of the other women, though I can’t think of any possibilities except Maria Gorman, Papa’s old friend from Communist Party headquarters. After all, Mama threw out her raspberry jam without even tasting it and never demonstrated any concern over her being arrested. Two clues to a marriage gone wrong. I suppose that’s not much less than most children get, so I shouldn’t feel so cheated.

Though maybe I’m all wrong about Maria’s having slept with my father and the frequency of his instances of infidelity; sometimes now I think of him as a chameleon, blending into situations and events. There’s so much about him I never understood.

At the time, I reason that there’s little point in my speculating further about Papa’s double life because the past is a puzzle whose pieces are already formed, and no amount of rearranging I might do will make those odd little shapes fit any differently. So maybe Tonio’s and Isaac’s advice to me was perfect. Still, couldn’t my father have waited more than four months to show Hansi and me that his heart is not with us? No stamina, as I’ve said.

A year has passed since the members of The Ring agreed not to see or talk to one another, so to celebrate their being able to socialize again Isaac invites Vera, K-H, and Marianne to Hanukkah dinner, and on the windy, bone-chilling evening of the 20th of December, I sneak up there for an hour, leaving Hansi in front of Harpo and his new underwater ballet partner, Chico.

As we await his guests, Isaac tells me, “I only hope we’ve spent enough time apart from each other to convince our traitor that we’re harmless.”

“Are you harmless?”

“Yes and no,” he says, pinching my cheek and looking at me lecherously.

He’s wrapped in his favorite cardigan sweater—brown, with holes at the elbows—and I’m wearing his floppy fur slippers and a scarf; heating an apartment is expensive and his business has been crippled by the Nazis.

Roman doesn’t join us; he’s with the Circus Cardinali for the winter. Rolf doesn’t come over either. None of us has seen him since Heidi’s funeral.

As soon as K-H and Marianne arrive, they offer me condolences and hugs for Mama’s death—and rub my new short hair with appreciative laughs. Vera does too, since we’re pretending we haven’t seen or spoken to each other.

K-H doesn’t take his probing eyes from me as we sip our wine and finally says, “I’d like to photograph you now that you’ve become who you were meant to be.”

How does he know? When I ask, he points to his eyes. “I’m trained to see,” he tells me.

When our guests ask after Hansi, I tell them about his scooping Groucho out of our tank and me flushing the murderous fish down the drain. Vera says we should have eaten him. “Goldfish are good on top of toast,” she says, rubbing her belly, “especially with a little horseradish.”

Despite her humor, Vera looks wan and tired, and I read in the obsessive way she smokes that she’s barely hanging on, but she assures me she couldn’t be better. As we sit down at the dinner table, I ask K-H and Marianne if they’ve spoken to Rolf.

“No, I’m afraid he blames all of us for Heidi’s death,” K-H tells me.

“Why does he blame you?” I ask.

“Because Vera and Isaac asked her to do some investigating.”

“Heidi discovered something that ended her life,” Marianne adds, “though we’ll never find out what it was.”

A statement I hear as a challenge … Did she learn the identity of the person who’d helped Georg to undermine The Ring? I let the conversation pass me by and look below the glass. Maybe it wasn’t something she knew but something she’d done that got her murdered. Could she have been the traitor who denounced Raffi and told the Gestapo where to find Vera? Someone did, so why not her? Which might mean that another member of The Ring took revenge and poisoned her.

“Oh, get this, Sophele,” K-H says indignantly, drawing my attention away from my speculations, “I got kicked off the deaf swim team for being Jewish.”

“And I got thrown off the bird-watching club for giants,” Vera adds sarcastically.

“Vera, I’d been on the team for seven years. I love swimming. It was a disappointment.”

“Oh, shut up! All we do is complain. We don’t do anything anymore. I hate it!”

Over the next hour, Vera snaps at the others a couple more times for their abandonment of the struggle. “Working with foreign journalists isn’t getting us anywhere!” she tells them.

“And working separately makes no sense.”

Depression settles over me because the solidarity these old friends once shared has vanished. K-H doesn’t even take pictures. I hadn’t realized that working together against the Nazis had given them not just a mission, but also such optimistic delight in one another, and now, disappointed in themselves, they will have to discover a new way to be together—if they can. Do they know that Isaac and I are lovers? I don’t sense any drumbeats of scandal beneath our conversation. After the first menorah candle is lit and Isaac leads us in Hanukkah prayers, it’s time for me to go home. He leads me to his door. I’m already two glasses of wine more dizzy than usual, which may be why I kiss him on the lips. He starts as if pierced by an arrow, but I want our friends to know I’m an outlaw—and to encourage them to keep battling any way they can. And maybe I even wish to live up to K-H’s assessment and be seen as myself. That was Mama’s goal and maybe it’s also my most important inheritance from her.

* * *

The next day, after school, I let myself in to Isaac’s apartment and find him in his usual sculptural position: sitting at his desk, hunched over his manuscripts. Except that this time he’s holding a big ivory-handled magnifying glass, and when he turns to me, he puts it over his nose, which grows the size of a pear. His eyes twinkle from the pleasure of making me laugh, but he doesn’t jump up to kiss me. Unusual. He lowers the lens as though the air has been let out of him. “Sophele, if I were ruining your life, you’d tell me, wouldn’t you?” he asks in a hesitant, concerned voice, which makes me feel as if we’re tiptoeing toward danger.

“Where’d that come from?” I ask.

“Last night, K-H, Marianne, and Vera thought I might be taking advantage of you.”

I roll my eyes, then comb his tufts of wild hair with my hand. We sit together, me on his lap. On my insistence, we talk of his childhood, which makes me feel sleepy in a good way. “I’m not too heavy, am I?” I ask every few minutes, and he just scoffs as if I’m being silly.

I like hearing his stories over and over. I like being able to lean against the reassurance of knowing what’s coming next; Mama’s death has made me that fragile and childlike again.

After we make love, he slips his arm under my head, and we talk about his wife for the first time. “For many years, she was my shadow, and I was hers,” he says. “Maybe we were even too close. Our son’s death drew us together but isolated us.” He shrugs sadly. “Then one day, I woke up and I looked all around me, and there was nothing there. A terrible thing to cast no image in front of you or behind you. Like not being born. Like living as a dybbuk—a ghost who haunts the earth.”

Knowing what he has lost makes me hold him tightly, and he doesn’t resist. His generous ease with me is why jealousy doesn’t poison us. Yet our intimacy makes me shiver after a time; the chill of being too naked in front of a lover. I stand up and fetch his magnifying glass. Sitting by him on the bed, I look at his lips—giant petals of a fleshy flower. I ask why he needs it.

“I want to see if Berekiah Zarco wrote any references to the Seventh Gate in the margins of his manuscripts … in tiny letters. I hate wearing my reading glasses and my vision isn’t what it used to be.”

“That’s because your eyes are no longer German.”

“True,” he replies, morosely.

“And I didn’t even know you had reading glasses.”

“Because they only get in the way. Sophele, Vera asked me last night to help her blow up Gestapo headquarters. We need to persuade her to emigrate before she kills somebody.”

Though maybe she already has murdered someone, I think, and I picture her wrapping her giant hands around Heidi’s throat and squeezing. I’d ask Isaac if he suspects her, too, but I’m pretty sure he’d lie to protect her. “Do you have Rolf’s address?” I ask him instead.

“Do me a favor and don’t see him,” he replies. He turns away from me abruptly, stands, and goes to the window. Opening the curtains a crack, he looks out.

“Why?” I ask.

“Because … because I’d prefer you didn’t. And I think that should be enough for you.”

The harsh way he talks to me makes me ask a question I didn’t know I had. “Isaac, you’re not involved in Heidi’s murder in any way, are you?”

“Me?” He turns to face me, outraged. “Heidi was a good friend of mine!”

“Still, if she were betraying you …”

“Do you think she was?”

“I have no idea. In any case, I promise I won’t break any Nuremberg laws with Rolf,” I joke, trying to ease the ill-feeling between us.

“You shouldn’t always try to be amusing,” he snaps.

He walks to his desk, where he’s left his pipe. Are we going to have our first fight? Perhaps, since I’m in no mood to cede him an inch of my right to be whoever I am. “I never thought I’d have to apologize to you for my sense of humor,” I tell him. “In any case, since you’re no longer a citizen, you don’t get a vote on how I behave.”

“You’re unstoppable.”

“Because I’m an Aryan. I’ve got honor and character.”

He gives me such a contemptuous look that I feel as if I’ve swallowed dirt. I get up and dress without a word. Who’d have thought our first quarrel would be so sickeningly silent? At the very least, I’d hoped for some smashed Mesopotamian crockery and Yiddish curses: May you grow six extra feet and not have enough money for comfortable shoes … ! This is more like a fight between two crippled hens.

He lights his pipe and goes back to reading, so self-contained that it leaves me bitter.

“So what’s Rolf’s address?” I say when I’m dressed.

“Kronprinzenstraße, Number 34, second floor. But if you visit him,” he tells me, as if it’s an order, “then go straight from school. We can’t be sure we’re not being watched, so I don’t want anyone following you from your apartment or mine. For all I know someone has a magnifying glass trained on us right now.”

Rolf lives in a dimly lit, gritty neighborhood that was built for workers at the Knorr break factory in Rummelsberg. I can’t go over in the early evening without Hansi, so he’s been dragging after me since we reached the Frankfurter Allee Station. My explanations about why I’m bringing him so far from home must not have landed in solid ground inside that miniature brain of his, so I have to threaten to do my imitation of King Kong subduing a dinosaur every few minutes or he might just start a sit-down strike on the slush-filled sidewalk and wind up with pneumonia, which I’ll have to pay for, since who else is going to care for him? Is he aware he’s slowly torturing me to death?

We’ve taken a circuitous route to get here in order to throw off anyone who might be on our trail. It has taken a full hour, and so we’re also half frozen—another reason for Hansi’s disaffection. Rolf lives in a handsome pink and white building with ironwork balconies. He answers my knocks right away, still mostly head and legs, but his hunchback has grown and makes him lean his head down cruelly to the left, as if he’s listening for squeaking in the floorboards. He’s clipped his hair as severely as a prisoner, and his eyes are smaller than I remember them—peepholes surrounded by deep wrinkles. He’s aged many years since I last saw him.

A glorious smile of surprise brightens his round little face, but he’s unable to lift his gaze all the way up to meet mine: “Sophele!”

I kneel down and we kiss cheeks. He stinks of cigar smoke. The whole apartment does. And it’s so cold that he’s wearing a long frock coat, midnight blue, undoubtedly Vera’s handiwork. “I think you met my brother once,” I say, reaching behind me for Hansi before he wanders off.

“Yes, of course. Come in, come in … !” He unfolds his arm graciously. “What brings you to this side of town?” he asks with a sweet smile.

“I just wanted to see how you were.”

He turns on the ceiling light, a white Chinese lantern. “I’m glad you came. Sit …” He points to a tattered black velvet couch with lumpy orange cushions. The coffee table between us is covered with dishes crusted with leftovers, including a rim of cheese that’s grown a smelly gray beard, and a nub of cigar. Seeing Hansi sniff at the offending smells, Rolf picks up all the porcelain and cradles the mess into the kitchen, saying, “My cleaning lady didn’t come this week …”

A crash makes me jump. I get the feeling Rolf is part of a club of Berlin widowers who grow towers of dishes in their sinks. Isaac is, of course, a charter member.

He questions me about my schoolwork and my parents, and he pats my leg stiffly when I talk of Mama’s death. I can see from his sheepish look that he thinks I might refuse a more intimate sign of his solidarity, so I kiss his cheek, which allows him to hug me. Happy with our renewed friendship, he shuffles eagerly off for his scrapbook, which documents his two decades in the circus. He sits between Hansi and me. The elephants and tigers in the background hold Hansi’s attention, but Rolf always points to Heidi. “There she is … you see her? And here I am.”

He’s a man who would notice his wife first even if she were photographed behind Jean Harlow. Rolf had a full head of luscious brown hair back then. A squashed, neckless Samson. In several pictures, he’s wearing gold Moroccan slippers, the kind with long curling toes.

“We had an act in which I played the servant of a clown who thought he was a pasha,” he explains. “When I think of the idiotic things I did …” He rolls his eyes.

Heidi wears her blond hair in braids in the old pictures. “She’d have made a much better Young Maiden than me,” I tell Rolf, which makes him grin.

Next, he brings in piles of napkins that he saved from the restaurants he dined in on his circus travels. My favorite is of ruby-colored lace. It glows like stained glass when I hold it up to the light. “That one’s from Prague,” he tells me.

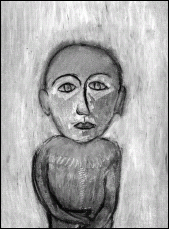

Rolf as a young man, dressed for a circus performance

He also shows us his cane collection—more than fifty. He keeps them in a beer barrel in his bedroom. His two favorites have white, ceramic monkey-heads. The devilish creatures are smiling cheekily, as if they’re hiding some glorious gossip under their tongues. “I bought them in Warsaw, in a Jewish antique shop,” Rolf tells us. “I was told they’re magic wands.” He holds one out to me and says, “Make a wish, Sophele, then blow on the monkey.”

I’d wish for Heidi to return, but that’s not likely to happen, so I think, Let Isaac and me outlast the Nazis. It’s in that moment that I learn I’ve given up any hope of sending Hitler back to his Vienna garret anytime soon.

Hansi reaches out for the cane, and Rolf lets him have it. The boy presses his lips to the monkey head for far longer than would be considered normal by most people.

“You can keep it if you want,” our host tells him sweetly, which prompts the boy to fold his lips inside his mouth and make a moaning noise. “Does he need to pee?” Rolf asks me.

“That just means ‘thank you’ in the Hansi Universe.”

“You’re welcome,” Rolf tells the boy, patting his leg.

“Sophele,” he suddenly gasps, “I think I see something for you, too.” Reaching behind my ear, he produces the napkin from Prague. “Voilà!” he says, beaming.

I kiss his cheek again and spread the fabric on my lap. “I’d forgotten what a magician you are.” Leaning forward to look across at my brother, I say, “Did you see what Rolf did?”

But he’s courting the monkey with his enraptured eyes and says nothing.

“Sophele, why don’t I teach you the trick!” Rolf exclaims. “You’ll be able to keep your kids entertained.”

After fifteen minutes, my hands have grasped the basic idea, and I practice so many times over the coming weeks that I learn to pull my mom’s old watch from behind Hansi’s ear.

Rolf and I talk for a time about the disadvantages of being three foot tall in a big city like Berlin, then about Paris, Budapest, Munich … Hansi falls fast asleep. As Rolf gazes at the boy, his eyes turn to liquid. He whispers, “Your brother is beautiful, beautiful, beautiful.” Schön, schön, schön …

Only a poet of the heart would say schön three times, and now I understand more about why Heidi adored him. And I can speak of important matters. “Rolf, Heidi was wonderful. I won’t ever forget her.”

“This may sound silly to you,” he replies, “but I never realized that her dying would be so very final. The lesson I’ve learned is that death is the only thing that never ends. You understand?” He locks his fingers, then pulls them apart. “The world has come undone … has been emptied of meaning. Like the story I just told you about Paris … All my stories are stones I toss out into the world in the hopes that one of them might make a dent that will prove I’m still alive. But they only prove the opposite—that I’m not really here.”

He talks so eloquently, and with such an effort to be understood by me, that I’m moved to tears myself. But I feel useless, too. So little good I can do for him …

“I’m being a terrible host,” he says, regaining his enthusiasm. “I’ll make us some tea, and I’ll put more coals in the stove. You poor things must be frozen.”

He and I go to the kitchen together, and while he busies himself with cups and saucers, I scrape the bearded cheese into the garbage and start soaking his dishes, which makes him tug me away from the sink. He’s a strong little man—a tiny tractor. Our struggle—back and forth—makes me burst out laughing. “We’d make a good comedy team,” I say.

After I get my way, and all the crusted porcelain is soaking nicely, he says, “Sophele, let me give you some of Heidi’s silk flowers.”

He leads me into his bedroom. Hansi is snoring, which makes Rolf grin as though he’s the cutest thing in the world, so I whisper, “Be glad you don’t have to sleep in the same room with the midnight express to Cologne. Sometimes I wish he’d derail.”

Rolf’s bed is only four feet square. His dresser comes up to my hip. We’re in Lilliput and I’m the awkward, oversized foreigner here.

“Look at this,” he says excitedly, and he turns the key in the bottom drawer, which is his hiding place for hundreds of silk blossoms. “When Heidi wasn’t cooking, she was sewing flowers. Vera taught her how. Take some. She’d want you to have them.”

I take a blue lily and a white rose.

“Vera says she hasn’t seen you in a while,” I say as he relocks the drawer. I use a light tone so as not to upset him.

He glares up at me. “So you’ve spoken to her about me?” he asks, as if I’ve committed a crime.

“Just once. The other night, she came to Isaac’s apartment.”

“I’ve nothing to say to her. Or any of the others.” He waddles out of the room angrily.

“But why?” I call from behind him. “They’re worried about you.”

In the kitchen again, Rolf angles his head up to meet my gaze as best he can, his tiny eyes flashing, his neck trembling from the effort to look up. “I’ll never forgive Vera for not opening her door to Heidi on the day she vanished. If she had, then …” He doesn’t finish his sentence because nothing now can save his wife from being murdered.

“Vera told me she asked you and Heidi to look into who might be betraying The Ring. Do you know if she’d discovered anything that might have gotten her into trouble?”

“We didn’t have much time to really ask around.”

“Do you have any idea who might have been informing the Nazis of The Ring’s activities?”

“No.” The water for our tea has come to a boil and Rolf begins to pour it into his pot.

“Do you think that Vera might have something to do with Heidi’s death?”

Rolf starts, spilling water on the oven, which hisses. “Shit!” he exclaims under his breath.

“Sorry. Did you get some on yourself?”

“No, I’m all right.” He secures the wooden handle of his pan with both his hands and holds it out from his body like a sword. When he’s done filling his teapot, he gazes out the window, capturing his thoughts. He looks younger in profile, and I can easily imagine him as a mop-haired little boy, dashing through his parents’ legs, delighted by simple things like silk flowers and cakes. I hope his parents recognized his bright nature as a gift.

“I considered the possibility that Vera may have been involved,” he tells me. “But Vera and Heidi were close. They had an understanding about women’s things, about …” He sighs at his failure to find the right word. “I can’t imagine Vera discarding Heidi in some lake. If I believed that, I couldn’t … couldn’t go on.”

After Rolf, Hansi, and I have had our tea, it’s time to go, since we have to reach home before Papa. At the door, Rolf waves me close to him and says, “Something odd has happened that I haven’t told anyone about.”

“What?”

“Sebastian Stangl, the doctor who fooled me and Heidi, who had her sterilized … He vanished, too, but no body has been found.”

“Did you read about him in the newspaper?”

“No, I went to his office just after I received the results of Heidi’s autopsy. I wanted to confront him for betraying us, but one of his nurses told me he’d already been missing for ten days. Two policemen came to interview me shortly after that. They searched my apartment and then brought me down to the station for more questioning. Then they released me. If they had any proof, I’d be in jail now. I’m pretty sure they’d need to have a body to accuse me of murder, in any case.”

“But you didn’t kill Dr Stangl, did you?”

“No, but I wish I had. Not that the police believe me. They’re still watching me. I can’t help thinking that there’s a kind of symmetry to what’s happened.”

“A symmetry?”

“Dr Stangl is now dead most likely, just like Heidi. I wouldn’t be surprised if he were lying in the Rummelsburger See. In fact, I’d wager everything I own, even Heidi’s flowers, that if the police find out what happened to him, they’ll discover who killed my wife, as well!”

On reaching home, I look up Dr Stangl’s number in the phone book, but I find only his office number. When I call, no one answers. I try several times the next day without any luck. It’s only on the following morning that a nurse named Katja Müller finally picks up and tells me I was lucky to find her in; she’s putting files into storage. She gives me Dr Stangl’s home number, since I tell her I’d like to express my sympathy to his wife. Mrs Stangl doesn’t answer that day, but I find her in the next afternoon. Her suspicion of my motives chills the line between us. When I explain about being a friend of Heidi’s, thinking that will warm her tone, she bursts out that she’s sure that Rolf has killed her husband.

After she calms down, she explains that Dr Stangl received a phone call on the day he vanished. “He left the house right away because the patient who called was in distress. Sebastian was like that … he’d go out in the middle of the night to rescue a friend.”

And then he’d sterilize them against their will, I think. “Who did your husband say the call was from?” I ask.

“Rolf.”

“Did your husband actually mention his last name?”

“No, but he said it was the dwarf. And to think of how many times my husband saw him after hours! If I could count the number of visits that little bastard made to our home for help … in the morning, at night … And my husband never turned him away. Never!”

“I think someone pretending to be Rolf lured Dr Stangl out on the evening he vanished,” I tell Isaac.

No answer. He talks little these days and spends nearly all his time studying Berekiah Zarco’s manuscripts. If I didn’t prepare him hard-boiled eggs and toast, he’d starve to death. Even so, his ribs have begun to show, and he looks a bit like a Picasso goat. Sexy in a desperate way. We’ve got the heat back on temporarily, though it’s still a bit chilly, and at this moment he’s sitting on the end of the bed in his bathrobe, scanning The Third Gate with his ivory-handled magnifying glass from Istanbul. I’m lying behind him on my side, propped on my elbow. My bare feet are warming against his back, because he’s the best oven in the world. No coal necessary. Just sex, toast, and eggs.

“Isaac, do you have any idea who might be able to imitate Rolf’s voice?” I ask loudly.

He looks back at me, annoyed that I’m disturbing him. “What makes you think Rolf didn’t do it?”

“He said he didn’t, and I believe him. Is that stupid of me?”

“Maybe a bit naïve.” He turns the page of his text and leans forward, so low that he looks as though he’s sniffing his ancestor’s sixteenth-century Turkish ink.

“Could Dr Stangl have been the person betraying The Ring?” I ask.

“Sophie, I’m trying to read!”

“Raffi is dead, and so is Vera’s baby. And now Heidi … I want some answers!”

“I never let Stangl in on our plans. I’m not that big a Dummkopf.”

“But maybe someone else did. You said that your circus friends had him as their doctor.”

He flaps his hand at me over his shoulder. A sign I should keep quiet, but I like testing his patience. “Did you like him?” I ask. “His wife seemed to think he was a saint.”

“A saint!” he exclaims in an outraged voice as he whips around. “He was a horror. Though it’s true that he was kind to us when I first met him.” He shrugs. “People change … he changed.”

Standing, he goes to his desk to look at another manuscript. He opens his bathrobe so he can scratch his balls. Then he tugs on their hairs. Maybe Tonio will enjoy the same mild torture when he’s pushing seventy.

“Isaac,” I say, sitting up, and when he doesn’t look at me, I make the cackling noise of a Berlin crow; I’ve discovered it works better than words.

“What is it?” he asks without turning around.

“Why do you think someone would kill both Heidi and Dr Stangl?”

He looks at me pleadingly. “Stop! I’ve told you before, I don’t like you running around Berlin asking questions about murders.” He gives me his fatal, squinty-eyed glare, but I’ve been vaccinated against his indignation by now.

“I’ll stop when I get to the end of the mystery,” I tell him. “That’s my Araboth.”

He lets his body sag. Another strategy to get his way—he wants sympathy for the frail old tailor who started working when he was ten. “I worry about you,” he says.

“I promise I’ll be careful.”

“Sophele, if you ever get into trouble, you are to come to me. Or call me. No matter what has happened, I’ll help you. Do you remember what mesirat nefesh means?”

“The willingness to go into the Land of the Dead to rescue a loved one.” I know what’s coming next, so I add, “You won’t need to make any sacrifice for me.”

“But if you do get into trouble …”

“You’ll be the first to know. I promise.”

His eyes brighten. “I want to give you a present. I thought of waiting until your birthday, but it’s too far away.”

“I think I can see what you’ve got for me,” I say, since his putz has begun to stir.

“Oh, you can have that old thing anytime you want it,” he says, stretching out his penis to do his silly imitation of an elephant trunk, then letting it fall. “No, I’ve got a real present for you!” Kneeling down, he takes out a red-wrapped box from the bottom drawer of his desk and holds it out to me. “Open it.”

Inside, I find a wooden case of forty-eight oil pastels, all the colors Chagall, Cézanne, and Sophie Riedesel might want, even that particularly helpless shade of gray that glazes over Isaac’s eyes when I lead him away from Berekiah Zarco to our bed.

After he’s spent and moaning on his back like a shipwrecked man on the Island of Insatiable Lovers—more to amuse both of us than from actual exhaustion—I take out the oil pastels and try to make a color portrait for the first time. But my hands and eyes are confounded by too many possibilities. It’s as if I’ve been handed a deck with 200 cards, and I make such a tangle of lines and colors that Isaac ends up grimacing and hiding his eyes from his lopsided likeness. Nobody born after the age of silent movies could make such a melodramatic face. The man has talent.

I try right away to sketch him again, but I’m unable to translate the textures and emotions of his face—the soft, tender folds of his eyelids, the shell-shadows inside his ears, his tired affection for me—into blue, red, and yellow. In fact, it takes months before I begin to feel as if I am coming to learn how to deal with color. Isaac says that it’s no wonder; the spectrum is one of the most powerful emanations of God, and the ability of white light to separate into its constituent parts is a very great mystery.

He also tells me that color symbolizes the joy of creation. “Imagine Adam when he saw the blue sky for the first time! Or Eve, when she held that red apple!”

“Was Eve wrong to eat the apple?” A question I’ve wanted to ask him for a long time.

“No, no, no. If she didn’t take the apple, we’d never have left Eden, and men and women would never know there was a world around them, or have any sense of themselves. In any case, Eve didn’t do anything that we all don’t do.”

“No?”

“Each of us in our lives takes a bite of that same apple in the moment before we first recognize ourselves in a mirror. We are all Eve, just as we are all Adam. And as we chew the apple, we say to ourselves, ‘I exist, and I am separate from God.’”

“So the snake isn’t evil?”

“No, the snake is eternity—the earth-born spark of eternity that starts the fire … the blaze in each of us. The snake is life recognizing itself, and knowing that we have a great deal of work to do while we’re here. Remember, the only hands and eyes God has are our own.”

“So why do people regard the snake as evil?”

“Because they think the world is made of prose when it’s made of poetry.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Because you’ve only just reached the Third Gate,” he says, kissing the center of my forehead. You’re just a little pisher who’s figuring out how to use her pastels.”

“When will I reach the Fourth Gate?”

“When you marry and have children.” Groaning he adds, “Though you’ll see it approaching when you start to have all the headaches that come with falling in love.”