“This country has a new public health problem—Congress and the FDA.”

—Dr. Joel J. Nobel, 1993

“We will surely live to regret the day we gave the FDA the kind of arbitrary power it is now exercising.”

—James O. Page, editor of Journal of Emergency Medical Services, 19921

If you asked the average American to name the single biggest problem with US health care, he would probably answer, “It costs too much.” Indeed, from 1960 to 2009, the “medical care” component of the Consumer Price Index grew an average of 1.8 percentage points more per year than the overall CPI. Measured in 2009 dollars, US per capita expenditures on health care rose from $1,066 in 1960 to a staggering $8,170 in 2009. Finally, expressed as a share of the economy, total American health care spending ballooned during this same period from 5 percent of GDP to 17.4 percent.2 This seemingly unstoppable growth in both the unit price and total expense of US health care was undoubtedly one of the main reasons for the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. As President Obama and his supporters framed the issue, it seemed that “the private sector” couldn’t provide affordable medical care to Americans.

After our historical survey in the first chapter, we know that such claims are completely erroneous. Even before the New Deal, time and again the government has ratcheted up its interventions in the markets for health care and insurance, driving up cost far above what it would be in a freer environment.

Broadly speaking, the government’s interventions in the market for health care can be grouped into two categories: (1) those that increase demand and (2) those that restrict supply. Putting these two together obviously pushes prices up; the laws of economics work the same in health care as in any other sector. (If the government started buying up apples at the same time it burned down half of the apple trees, what would happen to the price of apples at the grocery store?)

The first category of intervention, in which the government boosts demand for medical services and products, includes direct government payments (through Medicare and Medicaid). However, it also includes the tax code’s encouragement of third-party payment arrangements, which—as we have seen—weaken the incentives for end consumers to “shop around” and do their part to control medical costs.

The second category of intervention, in which the government restricts supply, is also important when considering what went wrong with US health care. One obvious culprit here is government-enforced medical licensing, which makes it literally illegal for people to provide various types of medical care without first jumping through numerous and expensive hoops. Another obvious culprit is the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which erects enormous hurdles in the way of companies trying to bring new drugs to market.

This chapter focuses on the FDA because it is a perfect example of how top-down government planning fails when it comes to medicine. As we will see, the FDA hits Americans with a double whammy. On the one hand, it prolongs the development of potentially useful drugs, leading to delayed treatment and artificially inflated prices. On the other hand, the FDA also fails to protect Americans from unacceptably dangerous drugs, even when experts in the private sector have raised alarm bells.

The FDA thus gives Americans the worst of both worlds: it makes it harder and more expensive to obtain quality treatment, while at the same time promoting the use of unacceptably dangerous products. By analyzing the operations of the FDA and its impact on drug development, this chapter will help explain why US health care costs have been rising so dramatically, and why more government intervention is not the answer.

The Food and Drug Administration was not organized under that name until 1930, but its regulatory functions were laid out in the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act.3 According to its website, the FDA’s current mission includes:

… protecting the public health by assuring the safety, effectiveness, quality, and security of human and veterinary drugs, vaccines and other biological products, and medical devices. The FDA is also responsible for the safety and security of most of our nation’s food supply, all cosmetics, dietary supplements and products that give off radiation.4

Most Americans have been taught to believe that the creation of the FDA was an obviously necessary event in US history. In the bad old days before the FDA, so the story goes, Americans had little protection from snake oil salesmen pushing poisonous products on an ignorant public. The normal market forces of competition could not be trusted to weed out greedy hucksters, because when it comes to medicine (and food), a dangerous product can mean death. This is why, so the usual narrative concludes, we need an agency like the FDA to set minimum standards of safety and efficacy, above which private companies can then compete for sales. The problem with this typical understanding of the FDA’s role is that in reality, there’s no such thing as a “safe” drug. Even water can kill you if you drink too much of it, too quickly. To take a less flippant example, imagine a new drug that promises an 80 percent chance of curing a certain type of cancer, but will cause a stroke in 1 percent of the patients who use it. Should the FDA approve such a drug? With these hypothetical numbers, it definitely seems “effective,” but is it “safe”? What if we kept reducing the percentage of cancer victims it would cure, while increasing the percentage of patients who would suffer a stroke? It’s not obvious where the dividing line should be drawn, and indeed readers would no doubt offer different opinions. Just as the FAA (Federal Aviation Administration) can’t really guarantee “safe” air travel—the only way to ensure zero plane crashes would be to ban all flights—the FDA can’t truly guarantee a “safe” supply of drugs. To completely eliminate the possibility of an impure drug causing a harmful side effect, the FDA would need to ban all drugs, which is clearly a cure worse than the disease.

At this point we need to briefly suspend our analysis of the FDA in order to provide you with a bedrock concept: the number needed to treat, or NNT. We urge you not to skip this section, even though at first you might not think the material is necessary to follow the historical discussion. We will return to the concept of NNT time and again throughout this book; it is critical that you give us a chance to explain the basics. Along with shedding light on the skullduggery of the FDA, awareness of this concept will allow you to far more knowledgeably evaluate the pros and cons of medications in your own life.

When it comes to pharmaceuticals, we have a natural tendency to give them a lot more credit than they deserve. We tend to think that a given drug is designed to produce a certain therapeutic effect—in other words, an effect that addresses a specific disease condition or symptoms—and that the therapeutic effect will be expressed in anyone who takes it. We also tend to think that the drug’s most dominant feature is its therapeutic effect and that side effects are minor nuisances that occur rarely or intermittently. We have even reached the point where we believe a well-crafted drug can produce a therapeutic effect devoid of unwanted side effects.

The actual truth is quite different. Therapeutic effects are intrinsically linked to side effects, and the degree of therapeutic effect has a lot more to do with the individual taking the medicine than with the intrinsic properties of the drug itself. As Hippocrates said, “It is more important to know what sort of person has a disease than to know the sort of disease a person has.”

For this crash course in NNT, we will first summarize Keaton’s Laws of Pharmacology, named in honor of one of our (McGuff’s) Pharmacology professor from Medical School, T. Kent Keaton, PhD.

1. Not all drugs have a therapeutic effect, and those that do depend on the presence and severity of a disease.

2. All drugs have side effects.

3. No drug has a single effect.

4. Side effects are proportionate to therapeutic effect.

5. Drugs can kill you.

Now let us elaborate on each of these laws. First, for a drug to have a therapeutic effect, there has to be an objective disease condition. Furthermore, the more serious the disease condition, the greater the likelihood that a therapeutic effect will be realized. When a disease condition is not present, what would have been a therapeutic effect has now become a side effect. For example, a person with very high blood pressure has a high likelihood of experiencing a therapeutic benefit from the administration of a blood pressure medicine, but a person with normal blood pressure will only experience the side effect of hypotension. A person with mild disease—such as borderline hypertension with only transient elevations of blood pressure—has a much lower likelihood of experiencing the drug’s benefit when his pressure intermittently spikes, and a much greater chance of hypotension during the majority of the day when his blood pressure is normal.

If we look at all people being treated with a particular medication for a particular disease, and view the disease as being expressed across a spectrum of severity, we can derive a number called the number needed to treat. This figure represents the number of patients with a condition that you would need to treat in order to confer benefit to one patient. This is called NNT-B (number needed to treat to benefit). Typically, a NNT-B of five is considered a pretty good therapeutic ratio, meaning you have to treat five patients in order to benefit one patient.

Now Keaton’s second law states that all drugs have side effects. This is not dependent on the presence of disease (at least not directly). With regard to a person with a disease state, there is a single desired “side effect” that addresses the disease state in question. When the disease state is present, the desired side effect becomes our therapeutic effect. The more severe the disease state, the more likely you are to have a therapeutic effect. When the disease state is less severe, there is a greater chance that the therapeutic effect will just revert to one of the drug’s side effects. In other words, we can simply state that a drug has a constellation of effects. If one of those effects improves upon a disease state we call it therapeutic, while all the other effects we call side effects.

Keaton’s third law is related to the second law. It is not possible to create a drug that has a single effect (the therapeutic effect). Human physiology is not that simple. It is impossible to isolate a single effect of a medication and eliminate all the others. When someone tells you a drug or supplement has a therapeutic effect, but no side effects, you are being lied to. In fact, this leads us to our fourth law.

The fourth law states that side effects are proportionate to therapeutic effects. This is true because a drug simply has a collection of effects bundled together. When one of these effects is directed at a disease state (or a marker of disease), it becomes a therapeutic effect and all the others become side effects. A popular TV ad for an over-the-counter antihistamine once claimed “side effects similar to placebo.” Well, guess what? If side effects were similar to placebo then the therapeutic effect also had to be similar to placebo.

The fifth law states, quite simply, that drugs can kill you. This law is related to the inverse benefit law we’ve described and requires an understanding of NNT. The number needed to treat is simply an expression of the power of the medication: it is the number of people that you need to give the drug to in order to see the effect in one patient. The NNT-B is the number needed to show benefit, as we mentioned previously. NNT-H is the number needed to show harm. NNT-B is dependent on the presence and severity of the disease state that the drug is supposed to treat. If a disease state is severe, the NNT-B will be small (it may take only five patients being treated in order to show benefit to one). If the disease state is mild, the NNT-B may be much larger (25 patients treated in order to show benefit to one).

Here is the problem: NNT-H does not depend on the presence of disease, because it is an effect that occurs independent of the disease state. Also, the other effects that contribute to NNT-H are additive, meaning that they can reinforce each other, lowering the threshold needed to cause harm to a patient. When a patient is taking two or more drugs, this additive effect can be greater than the sum of its parts because many drugs are metabolized by common pathways. When multiple drugs are metabolized in the same organ, they are eliminated more slowly and the circulating drug level rises, which disproportionately affects the NNT-H.

NNT-B and NNT-H are interrelated. Because there will always be a greater number of side effects than therapeutic effects, we must be careful to use a drug only in a situation where the NNT-B is a smaller number than the NNT-H. Since NNT-B is at a numerical disadvantage right out of the gate, the only way it can gain this ground back is to be given only to patients with the most severe disease. If someone has a severe disease, the NNT-B of a drug may be three and the NNT-H may be 10, but in someone with mild disease, the NNT-B may be 15 and the NNT-H remains 10. The simple presence of a disease is not an indication to use a drug; only if the disease is of sufficient severity should the patient consider doing so.

Now that we’ve given you a basic framework with which to think about the possible benefits and harms of pharmaceuticals, we can return to our analysis of the FDA.

When assessing the ways in which the FDA might be harming Americans, economists typically focus on the onerous restrictions it places on the development of new drugs. Economists are wont to focus on incentives, and when they consider those facing the FDA, they see reasons to expect the agency to err on the side of restriction rather than approval. As a recent study explained:

[T]he FDA faces asymmetrical incentives. Damage can occur when bad drugs are approved quickly or when good drugs are approved slowly. However, the cost to the FDA of these two outcomes is not the same. When bad drugs are approved quickly, the FDA is scrutinized and criticized, victims are identified, and their graves are marked. In contrast, when good drugs are approved slowly, the victims are unknown…. We know that some people who died would have lived had new drugs been available sooner, but we don’t know which people. As a result, premature deaths from drug lag and drug loss create less opposition than deaths from early approval, and the FDA’s natural stance is one of deadly caution.5

From our discussion of NNT, we know that the language in this quotation is a bit imprecise; in reality it’s too simplistic to classify drugs as either “good” or “bad.” Nonetheless, the authors of the study are pointing to an important phenomenon regarding incentives, which we can illustrate by studying the FDA’s response to two tragedies: thalidomide in the 1960s and Vioxx in the 2000s.

Let’s begin with thalidomide. Even though the FDA never approved commercial distribution—indeed President Kennedy would later honor the FDA reviewer who had denied the drug company’s application—American physicians nonetheless had received millions of tablets of thalidomide for clinical testing, and had distributed them to some 20,000 patients (though fewer than 1,000 of them were pregnant women). Though the impact in the US was fortunately contained, in the late 1950s and early 1960s more than 10,000 children in 46 countries were born with birth defects due to their mothers’ use of thalidomide during pregnancy.6 Ultimately the thalidomide tragedy increased the scope of the FDA’s powers, which the FDA itself explains in the following historical treatment taken from the FDA Consumer magazine:

All they wanted was a good night’s sleep, and a drug called thalidomide gave it to them. It brought a quick, natural sleep for millions of people who had trouble drifting off, and it also gave pregnant women relief from morning sickness. The drug’s German manufacturer claimed it was … safe for pregnant women….

By 1957, thalidomide was sold over-the-counter in Germany. By 1960, it was sold throughout Europe and South America, in Canada, and in many other parts of the world. To introduce it into the United States, the Richardson-Merrell pharmaceutical company of Cincinnati submitted an application to FDA in September 1960 to sell thalidomide under the brand name Kevadon.

The application was assigned to medical officer [Frances Oldham] Kelsey, who had joined FDA just one month earlier. It was her first drug review assignment…

Kelsey had concerns about the drug from the beginning… After Kelsey detailed these deficiencies in a letter to Richardson-Merrell, the company sent in additional information—but not enough to satisfy Kelsey.

… Kelsey did not cave under the pressure.

“I think I always accepted the fact that one was going to get bullied and pressured by industry,” says Kelsey. “It was understandable that the companies were very anxious to get their drugs approved.”…

The headline read “’Heroine’ of FDA Keeps Bad Drug Off of Market.” The story appeared on the front page of The Washington Post on July 15, 1962. Reporter Morton Mintz told the tale of “how the skepticism and stubbornness of a Government physician prevented what could have been an appalling American tragedy, the birth of hundreds or indeed thousands of armless and legless children.”…

In the wake of the furor these articles created, the American public soon came to realize how narrowly they had averted a major tragedy. And politicians who had been fighting for years for tighter drug controls were finally taken seriously.

A controversial bill introduced by Sen. Estes Kefauver of Tennessee several years earlier was resurrected from its congressional committee graveyard and rewritten. President Kennedy signed the bill generally known as the Kefauver-Harris Amendments into law on Oct. 10, 1962. This landmark drug law, which modified the earlier Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act of 1938, strengthened FDA’s control of drug experimentation on humans and changed the way new drugs were regulated.

Under the 1938 law, drug manufacturers had only to show that their drugs were safe. Under the 1962 law, for the first time, they also had to show that all new drugs were effective….

FDA grew along with its increased regulatory responsibilities. In 1960, Kelsey was one of only seven full-time and four young part-time physicians reviewing drugs at the agency. Today [in 2001—eds.] there are nearly 400 medical officers at FDA, but they are not as accessible to the drug companies as they were in the 1960s when Kelsey was pressured by the thalidomide manufacturer.7

We have included the lengthy quotation from the FDA Consumer magazine because it so perfectly epitomizes the image of itself that the FDA wants to inculcate in the minds of the American public. The FDA is portrayed as a band of heroic, selfless scientists and supporting staff doing their best to keep the American public safe from the unscrupulous sales efforts of big pharmaceutical companies.

Yet even on its own terms, this tale is somewhat odd. After all, the FDA hadn’t approved thalidomide, so it’s not clear why the 1938 scope of its powers was deemed inadequate. It would make sense for the other governments (such as Germany’s) that had approved thalidomide to review their procedures, but the US government was drastically changing the organization and mandate of the FDA at the same time President Kennedy was giving an award to Kelsey for doing such a great job under the old framework.

Adding to the irony, the obvious problem with thalidomide was that it clearly wasn’t safe for use during pregnancy. Why then, in response to the thalidomide tragedy, would the FDA’s powers be beefed up in 1962 to include the criterion of proof of efficacy, in addition to the long-standing proof of safety? To repeat, the problem with thalidomide was that it was dangerous for certain populations; Kelsey hadn’t been asking the manufacturer for evidence that thalidomide was effective.

Whether or not it was a rational response to the thalidomide experience, the 1962 expansion of the FDA’s powers came with a significant downside. Once again we turn to Milton Friedman, who explained the trade-offs in his bestselling book, Free to Choose. Writing in 1979, Friedman explained:

[T]he number of “new chemical entities” introduced each year has fallen by more than 50 percent since 1962. Equally important, it now [in 1979—eds.] takes much longer for a new drug to be approved and, partly as a result, the cost of developing a new drug has been multiplied manyfold. According to one estimate for the 1950s and early 1960s, it then cost about half a million dollars and took about twenty-five months to develop a new drug and bring it to market…. By 1978, “it [was] costing $54 million and about eight years of effort to bring a drug to market”—a hundredfold increase in cost and quadrupling of time, compared with a doubling of prices in general. As a result, drug companies can no longer afford to develop new drugs in the United States for patients with rare diseases. Increasingly, they must rely on drugs with high volume sales.8

As Friedman makes clear, the post-thalidomide expansion and transformation of the FDA’s powers in 1962 drastically curtailed the introduction of new drugs on the market. The enormous increase in development costs also changed the strategy of drug makers, who now had to focus on drugs with mass-market appeal in order to have any hope of turning a profit. The whole episode drives home the standard point that economists make when criticizing the FDA: because the public will be outraged if the FDA allows a drug with unacceptably dangerous side effects on the market, the agency has the incentive to proceed too cautiously, holding up potentially beneficial drugs for too long and artificially driving up the cost of drug development. In contrast to the quite visible victims of thalidomide, it’s not as obvious to identify the Americans over the years who have suffered or even died because the FDA stifled the development of a new drug that would have provided relief.

In addition to the thalidomide episode, we can see another illustration of this pattern with the 2004 voluntary recall of Vioxx by its manufacturer, Merck. But first we need to explain the historical context.

Largely because of the 1962 transformation of the FDA’s procedures in reaction to the thalidomide tragedy, the time it took the agency to review a New Drug Application (NDA) had grown excessively long: a typical NDA review took two and a half years, while some applications took eight years. The problem was not that any particular review involved such long consideration, but rather that the FDA was understaffed; applications might sit in a queue for years.

To address this problem, Congress passed the 1992 Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) “establishing renewable five-year periods of mandatory fees submitted by pharmaceutical companies along with their applications (as well as product and establishment fees).”9 Those fees allowed the FDA to hire hundreds of new employees. Because of the vast new manpower at its disposal, in the post-1992 PDUFA era the FDA tackled the backlog of drug applications, leading to a surge of approvals in 1996.

However, disaster once again struck in 2004—this time concerning Vioxx, a popular anti-inflammatory drug. The manufacturer, Merck, voluntarily pulled Vioxx from the market after a long-term study on patients at risk of developing recurrent colon polyps had to be halted “because of an increased risk of serious cardiovascular events, including heart attacks and strokes, among study patients taking Vioxx compared to patients receiving placebo.”10

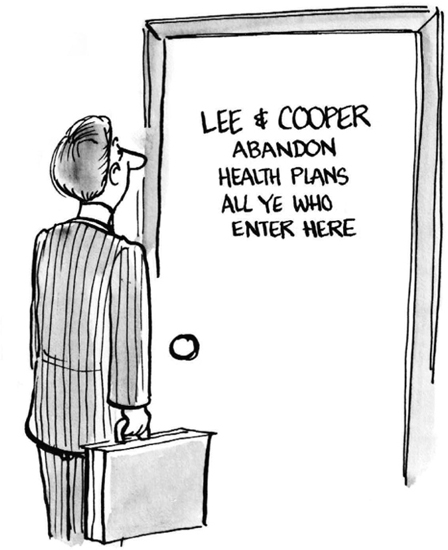

DON’T LEAVE YOUR HEALTH IN THE HANDS OF GOVERNMENT “EXPERTS”

The sordid Vioxx episode led an FDA whistleblower, David Graham, to declare that the agency was complicit in “what may be the single greatest drug safety catastrophe in the history of this country or the history of the world.”11

As with thalidomide, following the Vioxx bombshell the FDA reduced the approval rate of new drugs. Specifically, from 1993 through 2004—a period after the PDUFA reforms but before the Vioxx scandal—the FDA approved an average of 33.4 new molecular entities (NMEs) and new therapeutically significant biologics each year.12 Yet from 2005 through 2013, in the wake of the Vioxx public relations disaster, the FDA only approved an annual average of 25.3, a decline of 24 percent.13

“WHEREVER THERE IS MISLEADINGLY LABELED ORANGE JUICE, I’LL BE THERE …”

David A. Kessler, M.D. was Commissioner of the FDA from 1990 to 1997. According to the FDA’s bio page, “Dr. Kessler was sworn in on the same day that the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) was signed. Early in his tenure, he took action to protect consumers from misleading uses of the term ‘fresh’ in conjunction with processed or partially processed orange juice and tomato products, gaining himself the name ‘Elliot Knessler.’”14

What this cutesy description fails to convey is the absurd destruction unleashed under Kessler’s tenure. To take an example, on one occasion US marshals seized and destroyed 12,000 gallons of Procter & Gamble’s orange juice because it was labeled “Citrus Hill Fresh Choice.” (For what it’s worth, the juice had the disclaimer “Made from Concentrate” on the packaging, but FDA officials said the print was too small.) Kessler timed this raid to take place during a speech he was giving at a convention of food and drug attorneys, ensuring they realized there was a new sheriff in town.

Just to make sure the entire industry got the message, associate FDA Commissioner Jeff Nesbitt later announced, “The agency expects any and every company to make sure that its labeling is consistent with FDA policy, which has been in place for several decades. And if they don’t, and if the FDA finds out about it, then those companies can expect similar action.”15

In summary, we see that in response to public scandals, the FDA clamped down on its approvals, raising the barriers to the delivery of new drugs (and biologics) to patients. These episodes illustrate an incentive problem facing the FDA: because it receives far more negative feedback for approving drugs with dangerous side effects than for withholding drugs with useful therapeutic effects, the FDA will end up delaying or even totally preventing many suffering patients from receiving relief. If someone dies because the FDA does not approve a drug that would have saved his life, that death will be attributed to the illness, not to the FDA.

One mechanism of the harm (and silliness) of the FDA’s arbitrary power flows through its regulation of advertising. (Our account in this section draws on the analysis of Paul H. Rubin, in his contribution to a volume on the deadliness of FDA regulations.16) By the late 1980s, there was substantial evidence that a daily dose of aspirin could significantly reduce the risk of heart attack in middle-aged men. At the time, a package of BAYER would instruct the consumer, “Ask your doctor about new uses for BAYER ENTERIC Aspirin.” But the package itself did not specify exactly what these “new uses” might be!

The reason was that on March 2, 1988, the FDA Commissioner Frank Young told the relevant companies that if they advertised the use of aspirin to prevent first heart attacks, they would face legal action. Rubin describes the Catch-22 nature of the aspirin manufacturers in this situation, and explains why they didn’t go through the formal process to win FDA approval for the use of aspirin in first heart attack prevention:

The FDA’s approval process is costly, and it would cost some tens or hundreds of millions of dollars to obtain approval for aspirin as a heart attack preventative. Indeed, because the benefits of aspirin are so well documented, it might be impossible for ethical reasons to undertake such a study at all; researchers would probably be unwilling to deny any patients the benefits of aspirin, as is required in such a study. The one study cited previously … was terminated early because of the overwhelming evidence of the benefits of aspirin.17

Let us reiterate the Kafka-esque absurdity (and tragedy) of the situation: the FDA would not allow aspirin manufacturers to tell their customers about the medical benefits of their product in preventing first heart attacks, because these benefits had not been empirically validated in accordance with FDA protocol. Yet the reason the manufacturers couldn’t provide such evidence was that the benefits were so obvious, it would have been professionally unethical for researchers to conduct the relevant studies!

Later in his paper, Rubin also touches on the humorous aspects when discussing the FDA’s requirement of a “brief summary” in almost all advertisements of a drug. (The brief summary must include the “uses, side effects, and contraindications” of a drug.) However, the FDA allows that if an ad merely mentions the name of the drug but not its purpose, then the “brief summary” may be omitted. This rule led to some funny situations, such as a TV actor who “was forbidden from scratching his head during a Rogaine® commercial because the FDA believed that this indicated that the product was related to hair.”18

WARNING! SIDE EFFECTS MAY INCLUDE TUNING OUT …

Nowadays, it is commonplace for TV ads for a new drug to hire a professional speed-reader to zip through all of the horrible things that could happen to you if you use the product. When this practice first began, it struck many people as hilarious and also foolish: why in the world would a drug company pay good money to let people know its pill could give you diarrhea?

Yet in retrospect, it’s clear what has happened: precisely because the public is overwhelmed with every possible danger associated with every drug on the market, the information is drowned out. Nobody bothers trying to parse the actual warning. The assumption is: “If the FDA is letting them advertise this on TV, it must be safe.”

Although the standard economist discussion of the FDA is correct in pointing out its “deadly caution,” this is only half the story. At the same time that the FDA systematically keeps beneficial drugs off the market—or at least delays their introduction and makes them needlessly expensive—the FDA also approves unacceptably dangerous drugs, and is very reluctant to admit its mistakes even when the evidence is obvious. At first it might seem as if we are contradicting ourselves, but the two patterns are simultaneously true: the FDA gives Americans the worst of both worlds; it commits sins both of omission and commission.

Perhaps the best example we can give of the FDA ignoring clear evidence that it had approved an unacceptably dangerous drug is the tragic case of Vioxx, to which we’ve already alluded but will now give a fuller account. In the late 1990s, COX-2 inhibitors were the new darling of the drug market. They inhibited cyclooxegenase, an enzyme integral to the inflammation present in osteoarthritis. There was obviously a massive market for such drugs. Vioxx was approved for sale by the FDA in 1999. One year later, Merck, the maker of Vioxx, sent the results of a study (titled “Vioxx Gastrointestinal Outcomes Research” or “VIGOR”) to the FDA. Although there was much controversy over this study (and how Merck allegedly tried to spin its results in a positive light), the VIGOR results certainly raised red flags suggesting that Vioxx carried significant risks for heart attack, stroke, and sudden cardiac death. Yet it was not until April 2002 that these risks were even mentioned on the drug label, a shocking delay of two years that critics say indicates the cozy relationship between Merck and the FDA.

Then in 2004, reviewing the preliminary results of another trial (the APPROVe study), Merck shut down the study early and pulled Vioxx from the market—an action they took voluntarily without FDA direction. This was an extraordinary decision, making rofecoxib (the generic drug which Merck sold under the brand name of Vioxx) one of the most widely used drugs to be withdrawn from the market.

Even more alarming was a study performed by veteran FDA employee David Graham, MD, which was slated for publication in the November 17, 2004 issue of the British medical journal The Lancet. Graham’s study showed that Vioxx had caused 140,000 cases of coronary artery disease, with 60,000 of those cases being fatal. Yet for some reason, the article never appeared. Dr. Graham alleges he was threatened by the FDA. In an interview Dr. Graham gave with Newsweek, he stated:

I believe there were multiple levels of FDA management who wanted to keep the information of the magnitude of harm caused by Vioxx from the public and wanted to damage my credibility as a scientist. There’s no question in my mind that, had Merck not withdrawn Vioxx, it would still be on the shelves today and Americans would still be dying of heart attacks because of it. And this would be with the FDA’s full knowledge and complicity.19

The tragic case of Vioxx is extreme, but it is not isolated. Indeed, there are institutional biases in the current regulatory framework that prevent the FDA from achieving its ostensible function of protecting the public from dangerous drugs. We’ll explain the main forces at work in the remainder of this chapter. In doing so we rely heavily on the NNT framework explained earlier, which you may need to review to understand the discussion that follows.

NOT EVEN GOOD PEOPLE CAN FIX A BROKEN SYSTEM

“Since November [2004], when I appeared before the Senate Finance Committee and announced to the world that the FDA was incapable of protecting America from unsafe drugs or from another Vioxx®, very little has changed on the surface and substantively nothing has changed. The structural problems that exist within the FDA, where the people who approve the drugs are also the ones who oversee the post-marketing regulation of the drug, remain unchanged. The people who approve a drug when they see that there is a safety problem with it are very reluctant to do anything about it because it will reflect badly on them. They continue to let the damage occur. America is just as at risk now, as it was in November, as it was two years ago, and as it was five years ago.”

—2005 interview with David Graham, MD, 20-year FDA employee and senior drug safety researcher20

To understand why the FDA ends up giving a false signal of safety regarding some drugs, we need to review the rules governing the introduction and marketing of pharmaceuticals. During the FDA approval process, a new drug’s efficacy is assessed in patients with more severe disease, and furthermore, the drug is likely to be investigated in isolation and therefore not exposed to the effects of other medications that drive down the NNT-H.

Once a drug receives FDA approval, the manufacturer now has permission to advertise it as an “approved treatment” for a certain disease state. Once a drug gets marketed to physicians and patients, its use becomes more widespread; now people with milder disease are taking the drug, compared to those with more severe cases who were involved in the initial testing. Because of this change in the population taking the drug, there is an increase in the NNT-B (the number of people who need to take the drug in order to experience one case of benefit) and a simultaneous decrease in the NNT-H (the number of people who need to take the drug in order to experience one case of harm). Amplifying this problem is the fact that in the real world, most patients are on multiple medications for which their side effects are additive, which drives the NNT-H even lower. The end result is that the medication’s side effects become evident as the NNT-B and NNT-H become increasingly out of balance. This process explains why we so often find out a couple of years later about the dangerous effects of medications that started out as the “next great thing.”

FDA approval is based on a stepwise process that involves animal or basic science data (IND or investigational new drug), followed by clinical trials in humans, followed by provisional approval (NDA or new drug application).21 These studies are usually carried out by the manufacturer and are submitted to the FDA. This process naturally has the potential for conflicts of interest, a situation that was greatly exacerbated with the 1992 Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) in which the drug manufacturers began to literally provide the funding for the FDA to hire the staff who would then review their drug applications.

To be clear, we are not alleging that there is systematic manipulation of data involved, or that the researchers employed in the pharmaceutical industry on the whole are more dishonest than those in other fields. Rather, we are pointing out that the current system—with the FDA sitting atop a pyramid of control by the power of law—suffers from institutional biases that would be weeded out in a more competitive arena with multiple “authorities” providing expert product review. Under the current framework, the data about therapeutic effects and side effects for a new drug are collected under controlled and ideal circumstances. To repeat, what typically happens in a study (conducted by and reviewed by people who are all ultimately on the payroll of the manufacturer) is that a new drug will be tested on a population with severe disease who are not using other medications. This unrealistically places the NNT-B and the NNT-H in the best possible light, relative to the population of consumers to whom the drug eventually will be marketed.

It is not mere speculation on our part to suggest that a voluntary system of private review would produce better results than the current approach. For example, since 1993 the “Worst Pills, Best Pills” newsletter successfully predicted all 20 of the FDA’s withdrawals, in some cases years before the FDA actually reversed its initial decision. “Worst Pills, Best Pills” warned consumers about Meridia 12.5 years before its withdrawal, Zelnorm 2.8 years, Tequin 3.8 years, Bextra 2.4 years, Vioxx 3.5 years, Baycol 3.4 years, Propulsid 1.7 years, Rezulin 2.2 years, Raxar 1.4 years, Duract 0.6 years, and Redux 1.2 years before FDA withdrawal.22

No system is going to be perfect, but we can definitely improve upon the current framework in which the FDA simultaneously saddles pharmaceutical companies with arbitrary hurdles while giving the seal of approval to some drugs that have blazing red flags. Consumers would make more informed medical decisions in an open environment with competing medical “authorities” providing information on the potential benefits and dangers of new drugs, where reputation and track record determined the “power” of an opinion. It is commonplace for government agencies to waste money and underperform private-sector counterparts. Why would we expect anything different from the FDA?

The misunderstanding of NNT is behind a lot of polypharmacy (the use of four or more medications by a patient) and the harm that can come from it. Not understanding NNT also explains why so many physicians and laypeople tolerate the concept of inventing diseases to fit a medication. What if you are a drug company that develops a medication whose therapeutic effect is supposed to be a lowering of blood pressure, but you notice that one of the side effects is that it grows hair in balding patients? Well, you simply change it into a baldness medication that now has a side effect of lowering blood pressure (Minoxidil). What if you are working on a medication to treat a certain type of disease state and notice that a major side effect is an erection lasting a couple of hours, or that it makes eyelashes grow longer? Then you invent diseases that are really just normal parts of life (“male pattern baldness” or “erectile dysfunction” or “PMDD”), in the process creating a much larger cohort of people taking the medication. When greater numbers take a medication, the NNT-H shrinks. Inventing diseases creates a much broader market for a drug than exists with most legitimate diseases, which is why this has become such a common practice. The problem is, when there is no legitimate disease, the NNT-H will always exceed NNT-B.

What you should now be starting to see is a particular pattern that develops when the government is given the power to regulate. There is an immediate alliance that develops between the government and the dominant players in the industry to be regulated. A naïve observer might expect all private companies to adamantly resist government interference with their business. However, the biggest companies in an industry often recognize the advantages of costly new regulations. For one thing, they can more easily absorb the fixed compliance costs of filing reports and other mundane requirements. Yet more ominously, the dominant players can often gain credibility in the eyes of the public by obtaining the government’s “seal of approval”—a seal that is all too easy to acquire, because the government needs the expertise of industry leaders in order to develop those very regulations.

Having been placed in the prestigious consultant role, the industry leaders can then help frame regulations that hamstring the competition. The advantage that ensues gives the industry leaders even more dominance, which makes these companies incredibly rich. The money generated by government-favored companies gets funneled back to the government in the form of lobbying and regulatory fees. This entire process matures in a feed-forward fashion until ultimately there develops a “revolving door,” whereby CEOs of the dominant corporations end up serving a stint as the czar of a given regulatory agency that oversees their industry. It is hardly a “conspiracy theory” to suggest that this process invites corruption and fails to protect the public.

FDA: TAKING OUT THE COMPETITION

Another pattern of the FDA’s activities is that their most severe actions seem to be directed at non-pharmaceutical companies. Supplements in particular are a prime target for the FDA’s punitive powers. This seems odd given that the safety record for even the sketchiest supplements (such as those containing ephedra) is far superior to the safety records of pharmaceuticals. Certainly no supplement has ever caused 140,000 cases of heart attack or stroke with 60,000 fatalities, as did Vioxx!

Indeed, there is growing evidence that supplements may in some cases prove superior to pharmaceuticals.23 (For example, research suggests that SAM-e works as well as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and that omega-3 supplementation works better than statins.) Many critics plausibly argue that the FDA attacks the supplement industry so severely because they wish to suppress competition on behalf of their benefactors, the pharmaceutical industry.

We covered a lot of territory in this chapter. The takeaway message is that the FDA hits Americans with a double whammy: it hinders the development and marketing of genuinely useful drugs, while at the same time giving the public a false sense of security for drugs that are quite dangerous. We are not demanding the impossible; private-sector groups have a much better track record when it comes to drug evaluation.

Finally, we made it clear in this chapter that large pharmaceutical companies are not innocent babes in the wood when it comes to the scandals of drug development. Although ultimately the power flows from the government and its giant stick, “Big Pharma” has been involved in the revolving door corruption in which industry leaders join the ranks of those regulating their former colleagues.