On January 26, 1837, long-awaited good news came to the people of Michigan Territory.2 President Andrew Jackson signed legislation admitting Michigan into the Union as the twenty-sixth state. Its entry marked a doubling in the number of the original thirteen states, but superstition was not a cause of the more than two-year delay in achieving statehood. A border dispute with the state of Ohio, resolved only when Michigan relinquished its claim to Toledo and its Lake Erie harbor while accepting the bulk of the Upper Peninsula, prompted the detention.

Under the leadership of territorial governor Stevens T. Mason, who believed Michigan qualified for admission, steps were taken in 1834 and 1835 to demonstrate that condition. A census revealed that Michigan had more than enough population; Mason called for and helped direct a convention to draft a constitution. The effort went so far as the design of a great seal of the state to be used for official documents. To this day, it bears the date of 1835,3 representative of a populace who would beat down the door to enter into the Union.

Michigan came in as a free state. Ironically, it once had been slave territory because of French and British antecedents. Slavery existed in the Great Lakes territory at the formation of the nation; for example, the estate of William Macomb—namesake of Michigan’s third largest county—included twenty-six slaves. Contemporary histories described how the French aided Native American allies by keeping as slaves the enemies of those tribes. Statehood did not, however, commence eradication of the practice. That came earlier.

In 1787, the same year the U.S. Constitution was written and proposed to the original thirteen states, the Continental Congress approved a measure determining the future of the territory north and west of the Ohio River. This “Northwest Ordinance” decreed that from three to five new states would be created and join the Union “on an equal footing with the original States in all respects whatever.” A major difference, however, was found in this language: “[t]here shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.”4 Although outlawed, it was not until the British surrendered control of the territory in 1796 that the declaration was other than a paper statement. The antislavery provision made it into the ordinance in an interesting way. According to its chief drafter, he “had no idea the States would agree to the sixth Art. prohibiting slavery, as only [Massachusetts] of the Eastern States was present—and therefore omitted it in the draft—but finding the House favorably disposed on the subject, after we had completed the other parts I moved the art.—which was agreed to without opposition.”5 A strange twist of history helped make Michigan a land of liberty for all.

From such a serendipitous origin, the theme found its way into the original Michigan Constitution of 1835 in the ordinance-based phrasing of Article IX: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall ever be introduced into this state, except for the punishment of crimes of which the party shall have been duly convicted.”6 A year after the constitution process was complete and just months before statehood, delegates from southeast Michigan gathered at the First Presbyterian Church in Ann Arbor on November 10, 1836, for what they called an “Anti-Slavery State Convention.”7 The outcomes included establishment of the Michigan State Anti-Slavery Society, a series of resolutions attacking the institution of slavery in the Southern and border states and a decision to begin publication of an antislavery newspaper.

It would take some time—and some courage—to go to press, given events in a neighboring jurisdiction. In the fall of 1837 in Illinois, a proslavery crowd murdered publisher Elijah Lovejoy over his abolitionist articles. Within the next several years, though, three different antislavery publications would emerge in Michigan. Brothers William and Nicholas Sullivan published the first, the American Freeman, in Jackson in 1838. The next year, Seymour Treadwell began publishing the Michigan Freeman. Theodore Foster and the Reverend Guy Beckley launched the Signal of Liberty in April 1841 with operations above a shop on Broadway Avenue in Ann Arbor. This weekly publication included minutes from antislavery meetings across the state. All three papers sought to convince the rest of Michigan to support the nationwide abolition of slavery.8

Not all in the state concurred. Having three electoral votes upon its admission, Michigan initially supported presidential candidates of the antiabolition Democratic Party. Martin Van Buren carried Michigan in 1836, James Polk in 1840, native son Lewis Cass in 1848 and Franklin Pierce in 1852. While more Michiganders were voting for platforms that promised noninterference with slavery, others were aiding runaway slaves via the Underground Railroad that extended through the southern tier of the state’s counties.9 In June 1848, a convention gathered in Buffalo, New York, to select a ticket for the fall election. This “Free Soil Party” nominated Charles C. Foote of Michigan as candidate for the vice presidency of the United States.10 Support for their ticket siphoned votes from Cass’s run for the presidency.

Such differences were temporarily laid aside when Michigan troops marched off to service in the Mexican War. None saw combat, and the number involved was relatively small. Afterward, a veteran of the conflict moved to Michigan in April 1849. “I was ordered to Detroit, Michigan, where two years were spent with but few important incidents.”11 The young officer spent the time in a house quite nice for its day and of which he must have been particularly fond. Married less than a year earlier, here is where he brought his new bride, Julia, for their first extended time together. The couple’s first child, Fred, was born in Detroit on May 30, 1850. The clapboard-sided Greek Revival home with its adjacent grape arbor and garden were located on East Fort Street near the city center.12 The officer’s name would later be known to every American: Ulysses Simpson Grant.13

The Mexican War and its aftermath only exacerbated the slavery problem. A Michigan gathering14 of some fifteen hundred people disgruntled over the then dominant Democratic and Whig political machines changed the course of history.

By this time the people of Michigan were concerned with a problem that was every day more widely splitting the people of the United States. This was the problem of slavery…

Those who were opposed to slavery were dissatisfied with the old political parties. In 1854 a group of anti-slavery people called a meeting at Jackson, Michigan, to establish a new political party in which they felt they could have confidence.

So many people came to Jackson that there was no building large enough to hold the crowd. They met outdoors in what has been called the “Convention Under the Oaks” and chose the name Republican for their party. Several states claim to have been the birthplace of the national Republican party. Among these, Michigan has one of the strongest claims because of the convention at Jackson on July 6, 1854.

Michigan has an even firmer position in the beginning of the Republican party because of the election of 1854. Michigan’s Republicans won the election, and Michigan was the first state to have a Republican governor, Kingsley Bingham. The Republicans also won three of the four seats in the United States House of Representatives, as well as both houses of the state legislature.15

Born in New York State in 1808, Bingham opposed extension of slavery into the western territories of Kansas and Nebraska and, after serving in the same Congress as Lincoln, left the Democratic Party for the party of freedom. He was reelected as governor in 1856.

That year also meant a presidential election. Stumping for Republican nominee John C. Fremont, a former congressman from Illinois came to an August rally in Kalamazoo. Abraham Lincoln’s speech in Bronson Park did not excite reporters or many in attendance. His appearance suffered from the competing attractions: a giant “concourse” with a “free public table,” parades, eight bands and the Battle Creek Glee Club. Plus, four speakers’ stands were going simultaneously during the afternoon, so that the Detroit Daily Advertiser would lament it could assign only a single stenographic reporter to the speeches and added, “Our reporter stuck to the main stand.” Lincoln was preceded by remarks from Zachariah Chandler of Detroit and then introduced by Hezekiah G. Wells of the Republican executive committee.

This is partly what Lincoln said:

This government is sought to be put on a new track. Slavery is to be made a ruling element in our government. The question can be avoided in but two ways. By the one, we must submit, and allow slavery to triumph, or, by the other, we must triumph over the black demon. We have chosen the latter manner. If you of the North wish to get rid of this question, you must decide between these two ways—submit and vote for Buchanan, submit and vote that slavery is a just and good thing and immediately get rid of the question; or unite with us, and help us to triumph. We would all like to have the question done away with, but we cannot submit.

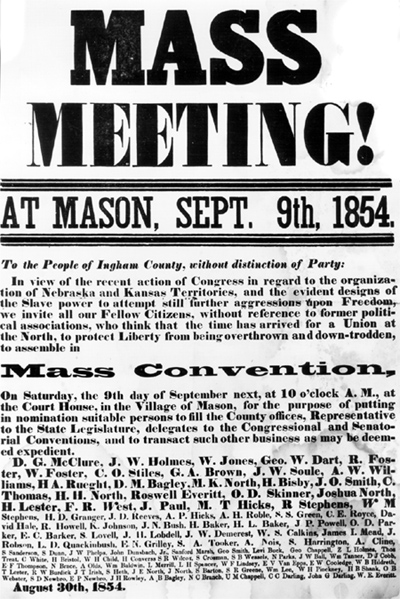

A broadside announces a mass meeting in Mason on September 9, 1854, to oppose “the Slave power.”

The nation decided, and James Buchanan won. His fellow Michigan Democrat, Lewis Cass, espoused their party’s political philosophy, which was quite different from the one held by Lincoln and his fellow Republicans. They held that the people of a territory ought to decide whether to authorize or prohibit slavery. Cass had risen to the top post in his party in Michigan, having served as territorial governor, U.S. secretary of war, U.S. senator, ambassador and presidential candidate in 1848. Buchanan named him secretary of state.

Two years later, the Michigan governorship was again on the line. Competing for the post were Democrat Charles P. Stuart and Republican Moses Wisner. Securing his law license in 1841, Wisner began practicing in Lapeer as prosecuting attorney thanks to an appointment by Governor William Woodbridge, a Whig. An abolitionist, Wisner participated in the 1854 gathering under the oaks in Jackson. His success as an attorney in Oakland County, exemplified by accumulation of almost six thousand acres of land, pushed him to prominence and led to nomination in the gubernatorial election in ’58. Running as a Republican to replace the state’s first governor from that party, Wisner beat Stuart, one of the sitting U.S. senators, by over nine thousand votes.16

As Republicans solidified their hold on Michigan, slavery opponents came from other states to seek support. On March 12, 1859, abolitionist John Brown of Kansas met with a number of prominent African Americans in a house in the heart of Detroit. A non-Michigander also attended by the name of Frederick Douglass. In this historic interracial meeting, Brown sought their assistance for an urgent, violent plan against slavery. Douglass and the Detroiters opposed the approach.17 Seven months later, Brown and a small cadre of followers stormed and briefly held the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. The slave uprising he sought to foment did not occur, and Brown was captured and hanged.

The state of Michigan was but twenty-three years old when it participated in the momentous 1860 election. Inhabited by nearly 750,000 free persons, Michigan ranked sixteenth in the nation and ninth out of the twenty-two Northern states in population.18 That year, Lincoln captured the Republican nomination for president and ran on a platform opposing the extension of slavery.19 He did not visit Michigan during the campaign, as was customary for candidates; William Seward of New York did stump for Lincoln20 in the state and received enthusiastic welcomes.21 Lincoln won; in Michigan, he took 88,445 votes compared to 64,958 for second-place finisher Stephen Douglas, the Northern Democratic candidate. In the country as a whole, Lincoln received 180 electoral votes, while his competitors received a combined total of 123. All 6 of Michigan’s electoral votes went in the Lincoln column,22 aiding his elevation to the White House.

The election outcome prompted South Carolina to bolt the Union the next month.23 A week before the Southerners’ decision, Lewis Cass resigned from the Buchanan cabinet, complaining that the administration was too “doughface” in the crisis that was daily escalating.24 It had not mobilized the Federal military or taken strong action to protect U.S. property. Cass was convinced that forceful action would have faced down Southerners who were threatening secession.25 His sentiments were echoed by other Michiganders, who watched as Southern states that had helped keep theirs out of the Union were now attempting to destroy what it had fought so hard to enter.26

Governor Wisner’s final address27 to the legislature in early 1861 did not mince words: “This is no time for vacillating councils when the cry of treason is ringing in our ears. The constitution as our fathers made it, is good enough for us, and must be enforced upon every foot of American soil.”28 On January 8, 1861, a salute of one hundred guns was fired in Detroit to honor the defense of Charleston Harbor when the garrison moved to Fort Sumter.29 On March 15, the legislature authorized Governor Austin Blair—another Republican—to supply troops to aid the federal government. News of the firing on Fort Sumter was received the same day it occurred, thanks to the telegraph. The thunderbolt shock of war that April Sunday when the fort surrendered found Michigan unprepared for the news—but the shock did not immobilize it.

Recall the great seal of the state of Michigan. In addition to bearing a date representing its fight to get into the Union, the seal featured an eagle, symbolic of the national bird, with yet another message, the phrase “E Pluribus Unum”: from out of many, one. Michigan had embraced the Revolutionary War–era motto, also found on the Federal seal, portraying that out of many colonies—or states—emerged a single nation, indivisible. And that is where Michigan came down as the nation’s flag was being lowered at Fort Sumter.