To say that Michigan performed her whole duty in her efforts to aid in suppressing the rebellion would not be saying enough; for, considering the low ebb of her finances at the time, it was an undertaking under great disadvantage, and especially so as Michigan, like most of the other States, had in the past made but a very feeble preparation, in a military point of view, to meet an emergency of that magnitude.30

The surrender of Fort Sumter prompted President Lincoln to call on loyal states for seventy-five thousand volunteers to put down the rebellion. It constituted a huge order. Michigan’s military force consisted of twenty-eight militia companies of 1,240 men. They were not organized into regiments or supported by sufficient public funds, since the state appropriation equaled just $3,000. Each company had to pay its own way; most were poorly equipped, all were poorly armed. In August the year before, the first-ever state encampment had met in Jackson under the direction of militia veteran Alpheus Williams of Detroit. It proved useful when the war started but hardly furnished a ready response.31

The antebellum legislature had been unmoved by arguments for bolstering the military:32 “Michigan, in common with other Northern States, had shared in the prevailing indifference” as to the prospect of armed conflict. “Thus the times of peace had not been devoted to a preparation for war.”33 In March 1861, while Fort Sumter effectively was under siege, an “act to provide a military force” was passed providing for recruitment of enough soldiers to form two regiments. They could drill up to ten days per month. One legislator, a former governor, sought to amend the bill by inserting “corn”—not referring to foodstuffs but to military leadership, i.e., “corn field officers.” No appropriations followed, and no implementation transpired.34

First responses to Fort Sumter were from ordinary civilians. When news arrived of the attack on April 13, lawyers in Detroit quickly convened at the bar library to avow their fealty to the Union. A day after the surrender, a Union meeting was held at the Firemen’s Hall. Lincoln’s call for troops was issued on April 15; the next day, Governor Blair responded with a trip to Detroit from Lansing, where he issued an immediate call for a regiment of ten companies. At a meeting later that day, when fulfilling Michigan’s quota would likely require $100,000, Detroit’s citizens pledged a loan of half that amount. “The amounts thus raised, as well as all other indebtedness incurred in like manner, were assumed by the State on the assembling of the Legislature.”35

Each succeeding day saw more mobilization, more esprit. At an April 17 ceremony, the American flag was ceremonially raised over the Detroit Board of Trade building and speeches were given in support of the Union; “General” Cass was present, lending his support. The Detroit Light Guards met up to organize for war service. On April 18, the flag was raised on top of the custom house and post office to confirm the security of Federal installations in the state. On April 20, a ceremony was held in front of the post office and an oath of loyalty administered to all government officials. The Sherlock, Scott and Brady Guards organized in anticipation of being called up. On April 23, the flag was again raised in a ceremony at Firemen’s Hall, and on April 25, it was flown over the city hall for a pro-Union speech by Cass and the singing of the “Star-Spangled Banner” by three thousand school children.

The War Department implemented Lincoln’s decree by assigning quotas to the various loyal states. Despite remonstrances by Governor Austin Blair that Michigan could furnish more, it was initially called upon to supply just a single infantry regiment. On May 4, the legislature made provision for relief of the families of volunteers who would respond.36 Many did, and the First Michigan Infantry was formed largely out of militia companies in Adrian, Ann Arbor, Burr Oak, Coldwater, Detroit, Jackson, Manchester, Marshall and Ypsilanti. On May 11 came a formal presentation of banner and cockades to the troop at Campus Martius. Two days later, the regiment left for the nation’s capital under the command of Colonel Orlando Willcox of Detroit, appointed by Blair to head Michigan’s first responders.

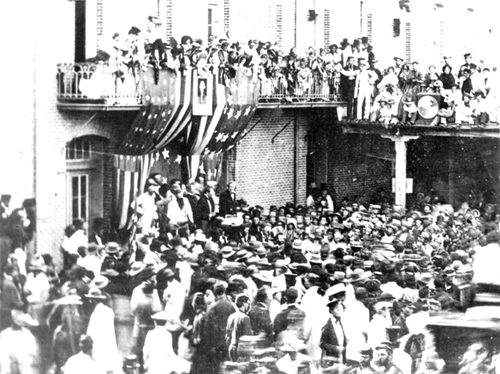

An oath of allegiance is said on April 20, 1861, before the old Detroit post office on Griswold, south of the first capitol.

Once the scales had fallen from its eyes, and the War Department increased its allotment, Michigan was springing into action. On June 2, the Second Michigan Infantry left the city. Many more soldiers in many other units would follow their path. The War Department designated Fort Wayne in Detroit as a camp of instruction from which many of Michigan’s troops were mustered, trained and dispatched to the front.

The emergencies and duties of the hour were then fully realized by the people of the State, and the uprising was universal…pledging fidelity and pecuniary assistance to the Nation in its hour of great peril, and volunteers in large numbers were congregating and demanding instant service for the Union, while the watch-fires of patriotism had been kindled on every hillside and in every valley, burning and flashing with intense brightness, at once cheering and inspiring.37

First Michigan Infantry receives a flag from “the Ladies & Citizens of Detroit” on May 11, 1861.

The trustees of Adrian College offered the use of campus buildings and grounds to the Fourth Infantry for training, a site named Camp Williams. The City of Adrian donated money to build a mess and dining hall. By early June, ten companies of the Fourth had arrived and started their training. On June 21, nearly thirty thousand people came to see them off to Washington. The women of Adrian presented the unit with a regimental flag bearing this admonition: “The Ladies of Adrian to the Fourth regiment Defend It.”

The Third Infantry marches down Detroit’s Jefferson Avenue in the June 6, 1861 edition of the New-York Illustrated News.

Similar events took place at Camp Owen in Marshall and other camps around the state. Not all found the traditional three branches appropriate to their skills. Over in Illinois, a regiment of engineers was being raised, and advertisements went out to neighboring states. In Michigan, with even more infantry companies being raised than the War Department had authorized, some saw the Illinois opportunity as their chance to serve. By end of summer, companies of engineers were forming in five Michigan communities to head to Chicago. Then, on September 10, four Grand Rapids businessmen met.

Surveyor Wright Coffinberry, master carpenter Baker Borden, merchant James Sligh and contractor Perrin Fox “decided that it would be better to raise an entire engineer regiment within the state and ‘thereby give Michigan the credit’ than to send companies elsewhere.” After securing the war secretary’s sign off on September 11, the four telegraphed the governor for his approval. Blair jumped on a train for Grand Rapids the night he received the telegram, met with the four on the morning of the twelfth and gave his approval so long as the regiment would be known as the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics. He telegraphed the secretary on the thirteenth of having “cheerfully authorized” the regiment. Adjutant General John Robertson issued General Order No. 76 on the same day, announcing the regiment’s formation. Four days is all it took to secure Michigan its most unique unit.38

Such support was not unusual. The First Michigan Infantry went off to war well organized: “Michigan sent off her first regiment fully armed, well equipped, fairly well drilled and in condition to at once take the field. It was ready to leave the state, and importuning for orders to do so, before those orders came.”39

They arrived in Baltimore on May 16 where, not long before, a Massachusetts regiment had been attacked by Southern sympathizers. The mob “was still there, but it did not venture to raise its hand against the Michigan soldiers.”40 The regiment safely went on to D.C. Arriving in the nation’s capital was exhilarating. The New York Tribune reported: “No regiment that has yet arrived has created such an excitement as the Michigan First.”41 An enthusiastic crowd came out to welcome the Michiganders, though it was 10:00 p.m., for they were “the first western regiment which had arrived at the capital.”42 Proceeding to the White House on the second day after arriving, the officers and band serenaded the president, were invited into the East Room and exchanged greetings.43

Michigan troops struck quite the image. One historian writes of how its earliest regiments were “formed of the hardiest of the state’s youth.”44 “These rowdy Michiganders would earn a reputation as being among the most ferocious fighters of the war, perhaps because of their rugged frontier background.”45 They did not have to wait long.

At 2:00 a.m. on May 24, the First Michigan went into action. Crossing the Potomac River on the Long Bridge, it stepped onto Rebel-held Virginia, a move that “was historic as the opening aggressive movement—the entry of the Grand Army of the Republic, as it was then named for the first time, upon the sacred soil.”46 It marched down to Alexandria to take back the city, cooperating with a regiment of New Yorkers. Their commander, Elmer Ellsworth, an associate of the president, was killed hauling down the Confederate flag from above a hotel. The Rebel troops fled at the appearance of the Michiganders, and Willcox had the honor of reclaiming the town by raising “the Stars and Stripes over the captured city.”47

Would the fortunes of war continue to smile on the regiment? At first, yes, as Willcox’s talent was rewarded with larger brigade command. The Union army prepared to advance on the Rebel force near Manassas Junction, Virginia, beyond a tributary called Bull Run. On July 21, the armies clashed as the Federals swept across the creek and around the left wing of the Southerners, initially gaining the upper hand. Willcox’s brigade came in on the far right of the Federal line. In the see-saw affair in that sector, the First Michigan advanced during a key moment to retake a battery of artillery that had fallen into Rebel hands. The regiment marched across fields and down the right side of Sudley Road, coming in at an opportune moment and rescuing the guns. Opening fire from the fence along the road, the left of the regiment drove off the Confederates and advanced to the point of woods south of the Henry House. The plan was to get into the Rebel rear and cause much mischief. But Willcox’s horse was hit, as was he in the right forearm. Captain William Withington of Jackson came up and led his commander into the woods, where he dismounted and attempted a return to the Union lines. A captain of a Virginia regiment confronted the two and took them prisoner.

The advance of the “Michigan regiment” into Alexandria in the May 24, 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly.

Also engaged in the battle were the Second and Third Michigan in the brigade commanded by General Israel Richardson of Pontiac and the Fourth Michigan in Willcox’s. Richardson’s troops fought their way across Bull Run and to a position opposite the Henry House, where they exchanged fire with Stonewall Jackson’s troops. The Fourth Michigan was on detached service at Fairfax Court House. Willcox’s after-action report noted that his old regiment “deserves the credit of advancing farther into the enemy’s lines than any other of our troops,” as their dead on the field proved.

Medal of Honor winner William Withington.

The return of the three-months’ regiment. Lewis Cass spoke at this event.

The fortitude of Michiganders was not cooled after the defeat and Willcox’s capture. The example of the four regiments helped spur continuing enlistments.48 As fall came on and the nation faced the reality that defeating the rebellion would require a long and hard war, Michigan men continued to be mustered into Federal service. “During the first year of fighting, twenty-one Michigan regiments were formed. Michigan men fought in most of the early battles of the war in the East.”49

Michigan was answering the call, and its efforts on behalf of the Union cause were not flagging.