The calendar page on the first year of the war had been turned. The first major battle at Bull Run had seen Michigan lose approximately one hundred men killed, wounded and missing or captured. The losses were chiefly from one regiment. Two others had covered the Union army’s retreat from the battleground and were the absolute final line of protection for the Federal troops. The second year of the war would prove to be one of much greater cost.50

In the spring, Ulysses S. Grant, now a general, was in command of an army in middle Tennessee readying itself for continuing the offensive he had embarked upon in February. After capturing Forts Henry and Donelson near the Kentucky border, Grant had moved down the Tennessee River toward a Rebel army at Corinth, Mississippi. The town was a march away of a day or so from his base at Pittsburg Landing. Early on the morning of April 6, 1862, the Confederates sprang upon Grant’s troops while they were still encamped. The Federals gave ground until a line of defense was constructed back at the landing, halting the Rebels after a daylong struggle. With the protection of nightfall, the Northerners regrouped. Reinforcements crossed the river to Grant, and the next day, his troops pushed the Confederates back past the Union campsites and into retreat. It was a battle known by the name of a rural church building near one of those camps—Shiloh—and it was a bloodbath.

Combined, the two armies suffered over twenty thousand casualties, far in excess of anything experienced in the war to this point. Grant’s force lost over thirteen thousand. Michigan troops—the Twelfth, Thirteenth and Fifteenth Regiments—were among those bloodied. The Twelfth was a component of the Sixth Division, under the command of Brigadier General Benjamin Prentiss, and of the First Brigade, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William H. Graves, of Adrian, who had been wounded at First Bull Run. The regiment was camped in the Union center at the tip of the spear in the position farthest toward the Confederates at Corinth. On the evening before the Rebel attack, Graves—still smarting from the defeat in the east—took it upon himself to order one company to reconnoiter into the woods ahead. Around 8:30 p.m., its captain reported back that long lines of campfires stretched out to his front, right and left. The report was passed up to Prentiss, who dismissed it, but Graves’s commanding officer thought different: he ordered a contingent, including two companies of the Twelfth, out in front as a trip wire in case an attack was imminent. The Rebels fell upon this advance picket at 3:00 a.m., and the great battle commenced. The Twelfth fought on during the day as part of three successive lines of defense, until the division was surrounded and many of its number captured. Prentiss was among those taken as prisoners. The Twelfth suffered over two hundred casualties.

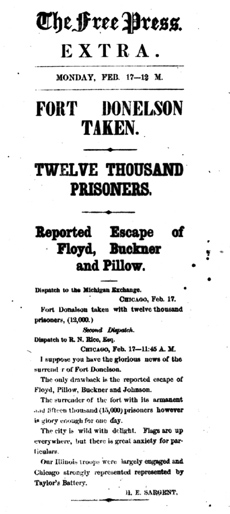

Detroit Free Press screams “Extra” on Monday, February 17, 1862, about the capture of Fort Donelson and twelve thousand prisoners.

The Fifteenth Infantry arrived at the landing on April 5, the day before the battle, and encamped. Lacking ammunition, it nonetheless advanced to the sound of battle the next morning. At first, it went into the fight with bayonets only, but after securing ammunition in the rear, returned to the action, losing over one hundred men. Such Michigan infantrymen were not the only units engaged. Battery B of the First Light Artillery fought at the Peach Orchard and near a pool that became known as the Bloody Pond. It stood its ground in the face of several charges but finally was overcome by superior numbers. Losing four of its six guns, half of the First’s men were also captured. Michigan’s soldiers had helped hold back the Confederate advance long enough for Grant to construct his line of defense, paving the way for victory.51

Back East, a new commander had a new plan to advance on Richmond to take the capital of the Confederacy and end the war in one fell swoop. In March 1862, General George McClellan transported most of his Army of the Potomac down that river to the peninsula between the James and York Rivers, anchored by a base of operations at Fortress Monroe on its eastern tip. Another wing remained between the two cities to protect Washington. In April, the Union force began cautiously moving toward Richmond. Not until early May did the first significant encounter result at Williamsburg. The Second Infantry went into action after a trying march, losing several officers and some sixty men in total. In one account of that fighting, a private who had received his weapon only the day before was found on the field beside a dead Confederate, both transfixed by the other’s bayonet. A young lieutenant from Michigan led a small detachment in an assault on a Confederate redoubt. It was the first real experience under fire for George A. Custer of Monroe, and his intrepid leadership earned him favorable mention in his commander’s battle report. The fighting near the colonial capital forced the Rebels back into the outskirts of Richmond.

Confederate commander Joseph Johnston developed a plan to drive the Union army away, but the Battle of Fair Oaks in early June resulted in his severe wounding and no favorable outcome, except for appointment of his replacement, Robert E. Lee. The new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia would become the Confederate general whom the Michigan units would confront in the East over the next several years. In a near-continuous fight known as the Seven Days Battles during the last week in June and on July 1, Lee took the offensive and drove McClellan away from Richmond. When the smoke finally cleared on the week’s fighting, over thirty-five thousand soldiers were casualties. Michigan troops had fought well,52 including an artillery commander born in Michigan during a key point that saved his army.

John Braden, Fifth Infantry (Detroit), was wounded at Williamsburg, Gettysburg and Locust Grove, Virginia. He was discharged at expiration of service in October 1864.

The Army of the Potomac had its back to the James River with Lee closing in. Nearby, on a sloping plateau known as Malvern Hill, a long line of cannons was placed in front of the blue infantry. As the gray lines moved into position, Detroiter Henry Jackson Hunt double-checked the position of his hundred guns. They opened up on the Confederate infantry units, as each attacked. When Rebel artillery attempted piecemeal counter fire, the Union batteries knocked them out of action one by one. The day was a disaster for Lee and became forever known for the central role played by the Federal cannons without serious infantry support. Hunt had so capably organized and managed the artillery here, defeating Lee. They would meet in similar circumstances a year later in Pennsylvania.

John Emory Crane, First Infantry (Hillsdale County), son of a Pioneer Wesleyan minister, died of disease in a hospital at Fort Monroe on July 4, 1862.

McClellan sought to reinforce and resupply his Army of the Potomac before resuming any forward movement. Lee took the opportunity to move his army back toward northern Virginia and require McClellan to follow. In late August, opposing forces met again on the battleground near Manassas.53 Lee dispatched one of his army’s wings under Stonewall Jackson to attack the Union line of supply, after which Jackson went into defensive mode to lure the Union troops into battle. The trap worked, and when Lee’s other wing arrived they smashed into the unprotected Federal left flank. The result was total collapse and retreat by the Union force.

Once again, a rear guard action on the road to Washington became necessary to save the United States army from destruction at Manassas. Federal cavalry came to the rescue. General John Buford, later of Gettysburg renown, shouted, “Boys, save our army, cover their retreat,” and the First Michigan Cavalry charged into the pursuing Confederates. The tactic succeeded, but at a high price. The colonel of the First Cavalry, Thornton Fleming Brodhead of Grosse Ile, was mortally wounded.54

During the fighting on the second day at Manassas, Michigan infantry was in place on both ends of the line. The Third Michigan held the right, and the First and Sixteenth were on the left. The latter two regiments were engaged in the assault on Jackson, crossing the field near Groveton under heavy artillery fire. As they attacked Stonewall’s brigades head-on, they became exposed to the flank attack. The Sixteenth was much cut up; the First, in a matter of minutes, lost eight officers and half of the regiment. Neither had anything to show for their courage under fire except combat laurels.

Lee continued as the aggressor. After Second Bull Run, he launched an invasion into Maryland, hoping to enlist sympathizers to the Southern side and European nations to recognize the legitimacy of the Confederacy. Splitting his army into several elements to collect provisions and recruits, he deployed several units as a screen in the mountain passes on his eastern flank to prevent McClellan from using them to attack before the separated fragments could reunite. On September 14, the Army of the Potomac sought to force the passes. The Seventeenth Infantry went into action at South Mountain; at midday, Confederate artillery opened up on the regiment as it supported the Union guns. After enduring the shelling for several hours, the regiment finally was ordered to attack the Rebels in the looming dusk. Their task was a daunting one: the enemy was posted behind stone walls at the top of the hill. Advancing up the mountain under heavy fire, the green regiment carried the Rebel defenses and drove the enemy back down the other side of the crest. The way was clear for McClellan to go after Lee. The regiment lost a third of their number but gained a nickname for its indomitable feat as the “Stonewall Regiment.”55 Its commander: Colonel William Withington, who was finally exchanged after his capture at First Bull Run.

John A. Clark, Seventh Infantry (Monroe), held the ranks of sergeant, second lieutenant and first lieutenant. He was killed in action at Antietam on September 17, 1862.

McClellan attacked Lee near Sharpsburg, Maryland, along Antietam Creek.56 He did so, however, in stages, allowing the Confederates to mount successive defensive lines. The Seventh Michigan went into action on the right of the Union line in the West Woods, under the command of Norman Hall of Fort Sumter fame. More than half the force engaged was disabled. Officers killed in this action were James Turrill of Lapeer, John Eberhard of Burr Oak and John A. Clark and Allen Zacharias of Monroe.

In the center, Major General Richardson led his division in an advance across open fields to a sunken road where Confederates lay in wait. The Federals were cut down in swaths. Richardson continued the attacks on this Bloody Lane until the Rebels were driven off with heavy casualties of their own—and until he was shot down. Taken to the rear, Richardson died several days after the battle.

After the success in the center, the left wing of McClellan’s army captured a bridge across the creek, enabling an advance on the remaining thin line of Confederates toward the close of the day’s action. Orlando Willcox advanced here on the left with a force that included the Eighth Michigan Infantry. He was pressing the Confederates back and nearing the town of Sharpsburg when ordered to withdraw. He would later wonder what might have happened if allowed to press his advance. The bloodiest day in American military history had ended. Some 350 Michiganders were killed or wounded, including the death of the highest ranking officer it sent to war.

Out in the western theater, opposing armies under Confederate Braxton Bragg and Union general William Rosecrans met at Perryville, Kentucky, in October. Both were searching for suitable supplies of drinking water during a particularly hot fall. Bragg attacked part of Rosecrans’s army with nearly all of his but, in a battle that could have gone against the Federals, it ended up withdrawing. Battery A of the First Light Artillery under Cyrus Loomis of Coldwater played an important role. It was reported to have fired both the first and last shots of the day’s action. It fought a lengthy duel with the Washington Artillery of the Confederate side; it repelled five charges; and it claimed to have saved the Union right flank. The battery suffered eighteen casualties and lost thirty-three horses.57

The year ended in disaster for the Army of the Potomac. In December, it stole a march on Lee’s army, but a logistics failure prevented pontoon boats from arriving across from the town of Fredericksburg when the army could have marched into the town and onto the heights beyond. By the time bridge-building apparatus was on the scene, so was Lee. Attempts to force a landing were thwarted by sharpshooters firing at the Federal bridge builders from hidden locations in houses and structures in the town.

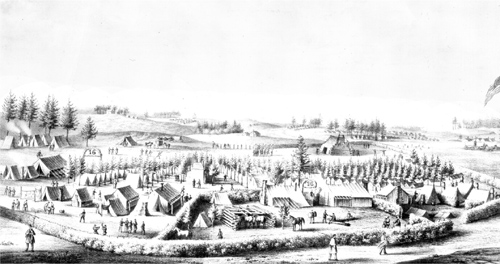

“Camp of 16th Michigan Regiment near Fredricksburg [sic],” a lithograph by A. Hoen & Co., Baltimore, December 13, 1862.

At first, Union infantry units were moved into position to provide cover for the engineers. When that proved ineffective, volunteers were sought to cross the river and eliminate the Rebel snipers. Henry Baxter of Jonesville, colonel of the Seventh Michigan—at the request of his brigade commander, Colonel Hall—agreed to storm the town.

Hall’s after action account is thus:

I stated to Colonel Baxter that I saw no hopes of effecting the crossing, unless he could man the oars, place the boats, and push across unassisted. I confess I felt apprehensions of disaster in this attempt, as, without experience in the management of boats, the shore might not be reached promptly, if at all, and the party lost. Colonel Baxter promptly accepted the new conditions, and proceeded immediately to arrange the boats, some of which had to be carried to the water…The boats pushed gallantly across under a sharp fire. While in the boats, 1 man was killed and Lieutenant Colonel Baxter and several men were wounded. The party, which numbered from 60 to 70 men, formed under the bank and rushed upon the first street, attacked the enemy, and, in the space of a few minutes, 31 prisoners were captured and a secure lodgment effected. Several men were here also wounded, and Lieutenant Emery and 1 man killed. The remainder of the regiment meanwhile crossed.

The one fatality was Lieutenant Franklin Emery of Lapeer.

According to later accounts, the Michigan troops included Robert Henry Hendershot, who became known as “the Drummer Boy of the Rappahannock.” Like Michigander Charles Gardner, he was a drummer for the Eighth Michigan. His regiment was stationed near the Seventh, and when it was crossing the Rappahannock under fire, it was said that young Robert ran to help push the boats. He had crossed the river when a shell fragment hit his drum and broke it into pieces; picking up a musket, he encountered a Confederate soldier and took him prisoner. The story of a boy capturing a Rebel made him a hero.58

George W. Curtis, First Infantry (Houghton County), enlisted at age thirty in July 1861, reenlisted February 17, 1864, and was wounded in action on March 29, 1865.

During assaults on Confederate positions beyond the town, much of the Michigan infantry was held in reserve. The First again was called upon to participate in an assault with little chance of success. They suffered losses while forming for the assault in town and then took more casualties as they tried to take the heights. Captain J. Benton Kennedy of Jackson was mortally wounded while leading his company. Remaining on the field until dark, the regiment was not withdrawn until late the following day. The experience of the Fourth Michigan was much the same: being ordered into action, left on the field overnight and withdrawn after the loss of a number of enlisted men and Lieutenant James Clark of Ann Arbor. Covering the assaults was the artillery fire from across the river of Henry Hunt.59

The very end of the year brought about an unusual action. At the Battle of Stones River near Murfreesboro, Tennessee, armies under Rosecrans and Bragg fought on December 31, 1862, and New Year’s Day 1863. Both commanders planned an attack on the other’s right. After the two days, Rosecrans claimed victory when Bragg withdrew. It would take over a century for commemoration of the role played by Michigan soldiers in a number of units during the battle. The text of the 1966 monument revealed that the marker is

dedicated to all the Michigan soldiers engaged in this great battle, to the seventy-one men who lost their lives and to the six regiments which fought bravely for their country: Twenty-first Michigan Infantry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel William B. McCreery (Flint), 18 killed, 89 wounded, 36 missing; Eleventh Michigan Infantry, commanded by Colonel William Stoughton (Sturgis), 30 killed, 84 wounded, 25 missing; Thirteenth Michigan Infantry, commanded by Colonel Michael Shoemaker (Jackson), 17 killed, 72 wounded; Fourth Michigan Cavalry, commanded by Colonel Robert H.G. Minty (Detroit), 1 killed, 7 wounded, 12 missing; First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics, commanded by Colonel William P. Innes (Grand Rapids), 2 killed, 9 wounded, 5 missing; First Michigan Artillery Battery, Company A, commanded by Colonel Cyrus O. Loomis (Coldwater), 1 killed, 10 wounded, 2 missing. Michigan men fought at Stones River for the preservation and perpetuity of the Union.

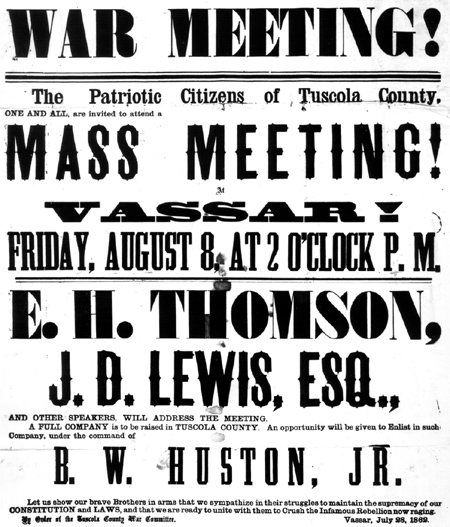

A Tuscola County “Mass War Meeting” is announced on July 28, 1862.

The year closed with significant Union victories out West—despite missteps—and no significant change in affairs in the East. The casualties had mounted far beyond expectations; huge portions of Confederate territory were in Union hands, but the Rebel capital remained defiant. Warfare during 1862 did produce one seismic shift: after the Battle of Antietam, Lincoln announced that, on the first of the new year, he would issue a proclamation freeing all slaves within Confederate territory. On the same winter’s day, Michigan troops were fighting along a river in central Tennessee when Lincoln inked his name to the war measure that achieved liberty for millions of Americans in the rest of the South. The Emancipation Proclamation was celebrated by many in Michigan, including its Republican leadership.

The war was continuing, but America would never be the same.