The waters outlining Michigan do more than shape the state and provide recreational outlets for its citizens; they have served as a moat, providing protection from hostile forces. Like all such water-based defenses, however, they require only appropriate countermeasures to make them ineffective. At several points, geography places Michigan in proximity to a foreign nation. In 1861 at Detroit, the guardian of the boundary was Fort Wayne, a muster point and drill ground for Michigan troops before they headed off to the battlefield. Far up at the Soo, Fort Brady served as the first line of defense. Military installations at Mackinac Island and other locations also resisted the potential of attack. Almost the entire Michigan–Canada border, though, lay miles from shore in the middle of Lakes Superior, Huron and Erie. Today, that line is the longest undefended border in the world. A century and a half ago, Canada’s connection to Great Britain and its proximity to northern states like Michigan shaped a different strategic setting.

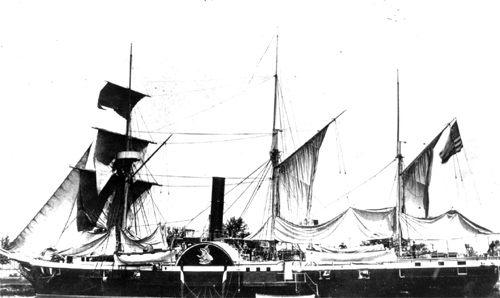

A single warship plied the waters of the Great Lakes in defense of the United States. The USS Michigan was a paddle steam frigate, but its significance eclipsed that status as the lone navy ship on the inland seas. Constructed in 1842 and launched the next year, it was the first iron-hulled steam warship in the U.S. fleet. Its mission was to guard four of the five Great Lakes, omitting only Lake Ontario because of the falls at its western end. The vessel’s armament consisted of “pivoting shell guns mounted on its centerline,”75 a revolutionary improvement in firepower. The Michigan could outrun any ship afloat, and, in case of battle damage, its system of watertight compartments improved the likelihood of continued buoyancy. Forerunner to the famed USS Monitor, the iron vessel was designed to act independently of a fleet and either outgun or outrun its enemy.

USS Michigan.

The Michigan was a player in the “battle of Lake Erie,” the most spectacular maritime incident on the Great Lakes during the Civil War. On September 19, 1864, the passenger steamer Philo Parsons departed Detroit bound for Sandusky, Ohio. Such an excursion was a forerunner of the trek millions of Michiganders would later take to that below-the-border destination to experience a different kind of wild ride. At a couple points along its route, the ship took on passengers who actually were Confederate plotters intent on using the ship for a daring exploit. Their plan: attack and capture the Michigan, free thousands of Confederates imprisoned at Johnson Island near Sandusky and convert the warship into a Great Lakes raider for the South. Not only would the Confederacy gain a significant manpower increase—among the captives were seven generals and the son of former vice president John C. Breckinridge—it would receive a huge morale boost. And the captured ship would wreak havoc on commercial traffic all through the lakes and St. Lawrence rivershed, mirroring destruction of Northern merchant ships on the oceans.

On land, a key player was a veteran of Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry. On water, the mastermind was a Scotsman with experience in irregular warfare. Gaining control of the Philo Parsons by force (several crewmembers were injured) just past Put-in-Bay before its arrival at Kelley’s Island, the Rebels redirected the vessel toward Sandusky Bay and the island prison camp just inside. The plan was abandoned, though, when most of the plotters grew fearful that the formidable Michigan, anchored in the harbor, had been warned. In truth, the plot had been uncovered. Turning about, the Philo Parsons headed back to the Canadian side of the Detroit River for an escape. Though most fled successfully, some Confederates were captured and imprisoned at Johnson’s Island, an ironic outcome given their mission. When in range of the Michigan, the task of trying to take the warship proved too much. Its design had worked even without firing a shot.76

For Michigan’s neighbors, the American Civil War would influence the shape of the Canadian confederation to come. While they may know something about the war, “[f]ew Canadians realize that, although it was primarily an American tragedy, it also stands as a defining event” in their history.77 Tens of thousands of Canadians fought in the war78 —some five thousand died—and twice during its course, Canada, as a constituent part of Great Britain, approached belligerency with the United States. History has treated the northern front as a sideshow, yet the Confederacy’s failure to use Michigan’s northern neighbor as a staging ground to open a second front contributed to the final outcome.

With its thousands of miles of fresh water coastline and a fast-moving river that flows by its largest city, Civil War Michigan could be expected to field a large contingent of sailors for the U.S. Navy. The identity of most is not known, but one mariner from Michigan deserved a better fate.

Detroiter William Gouin enlisted at Boston, Massachusetts, on January 1, 1862. He began his navy service on board the USS Ohio before transfer to the USS Kearsarge. The sloop-of-war was designed to hunt down Confederate raiders, and on June 19, 1864, it discovered the CSS Alabama in the harbor at Cherbourg, France. The exploits of the Alabama in attacking and sinking Union merchant ships was already legendary. Rather than holding in or making a run, the Alabama came out to face the Federal warship—and in an hour was ablaze and sinking. The superior firepower of the Kearsarge and its defensive armament gave it the advantage. Remarkably, the U.S. ship’s crew suffered only three wounded in the battle and one killed. Seaman Gouin died on June 27, in the hospital at Cherbourg from wounds received during the engagement.

A surgeon aboard the ship recounted his impressions of Gouin:

[Gouin’s] behavior during and after battle were worthy of the highest praise. Stationed at the after pivot-gun he was seriously wounded in the leg by the explosion of a shell; in agony, and exhausted from the loss of blood, he dragged himself to the forward hatch, concealing the severity of his injury, so that his comrades would not leave their stations for his assistance.79

Though the only fatality, Gouin was not the only Michigander aboard. Fred Walden, also of Detroit, had enlisted for service as a coal heaver on the Kearsarge at Cadiz, Spain, on January 26, 1864, under the alias of John Pope. He also experienced the memorable sea battle and was discharged on November 30, 1864.80

American naval lore includes Commodore Dewey’s famous order at the Battle of Manila Bay during the later Spanish-American War, “You may fire when ready, Gridley.” The latter officer was captain of the Olympia, flagship of Dewey’s squadron and a Civil War veteran. Charles V. Gridley had two Michigan connections. He was “attached” to the Michigan on the Great Lakes from 1870 to 1872. First, though, he had been appointed to the Naval Academy from Hillsdale, Michigan. An Indiana native whose family moved when he was quite young, he attended Hillsdale College until obtaining an appointment to Annapolis at age sixteen on September 26, 1860. Graduating in 1863, he served as an ensign aboard the USS Oneida from 1863 to 1865 as part of the West Gulf Blockading Squadron.81 During the Battle of Mobile Bay in August 1864—occasion of another famous naval expression—his conduct received commendation as “beyond all praise.”82 Ironically, Gridley’s final resting place is Erie, Pennsylvania, the port of station for the Michigan.

A complete accounting of the service of Michigan sailors is not found in postwar reporting. The record does reveal that 598 enlistments were credited to Michigan by the War Department. Of the 13 regular officers listed in the Michigan adjutant general’s compendium, 2 served during the war in the U.S. Marine Corps, 1 commanded a ship in the assaults on Fort Fisher, 3 served aboard Admiral David Farragut’s flagship USS Hartford, 1 served on the Michigan and 1 fought in Farragut’s squadron at Vicksburg and Port Hudson. Several were wounded in action. “Of the services of Michigan men in the navy, during the war, there is unfortunately but little on record.”83 History may not have adequately written up their contributions to eventual victory, but that is history’s fault.