On the southeast corner of the state capitol grounds in Lansing, more hidden than others, is a realistic statue of a Michigan soldier. The image is not just of any infantryman aiming a rifle. In October 1915, a half-century after the war and with the legislature’s approval, the survivors of the First Michigan Sharpshooters came to town to dedicate their monument. Always a resourceful bunch, despite diminished numbers they had raised the necessary funds themselves.

From much of Michigan and from all walks of life they had been recruited for the Union army. Mustered in on July 7, 1863, the regiment saw action west of the Appalachians in defending against Morgan’s Raid and then made its way east to fight at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania and Petersburg. The regiment was credited as one of the first two units to enter Petersburg in April 1865 after its forced abandonment by Lee’s army. An inscription on the monument states that of a total enrollment of 981 soldiers, 113 were killed or died of wounds, 41 died as prisoners of war, 109 died of disease, 353 were discharged for wounds and disability and 365 remained to be mustered out on August 7, 1865.

Among that number were 145 Native Americans. From mostly the northern part of the Lower Peninsula, these men wore Union blue for a Michigan unit. Although they made up a small percentage of the total enrolled, each one had agreed to risk his life on the battlefield to preserve the United States of America. The adjutant general’s report does not refer to them as Native Americans. That term was reserved for those who were not first-generation immigrants. Rather, the report simply calls them Indians. Nonetheless, it does not appear to tally them in the “Total foreign” column but in the “Total Americans” figures. Despite nineteenth-century America’s outlook, these Michiganders fought in the struggle for freedom and equality.84

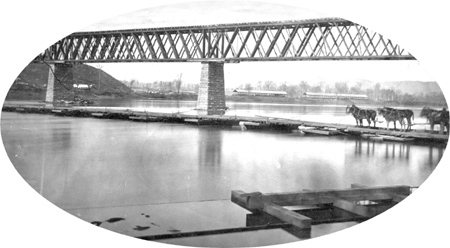

The “Michigan Bridge” built by the First Engineers and Mechanics at Bridgeport, Alabama, in 1863.

During a later contest that touched on the same themes, actor John Wayne starred in a motion picture portraying The Fighting Seabees. These “construction battalions” performed their duties under hazardous conditions in the Pacific theater, arriving on the scene soon after the Marines to erect buildings, construct airfields and build bridges. They were trained to return enemy fire when necessary. Nearly a century earlier, the Seabees’ forerunners were enlistees in the First Michigan Engineers and Mechanics. The regiment was comprised of artisans, craftsmen, railroad men and engineers, whose work advanced ultimate victory for the North by building and maintaining the infrastructure upon which the Union armies depended. And they fought Confederate units when attacked. Frequently separated by many miles due to the far-flung nature of their projects, the soldiers and their officers kept supply lines open, telegraph messages flowing and fortifications strengthened. Their bridge-building—a precursor to an iconic Michigan structure that would later link its two peninsulas—was a signature skill.85

In December 1862, a unique command was formed from three regiments of horse soldiers, all from the same state, united under one general officer. The Army of the Potomac veterans would become “the only cavalry brigade in the service made up entirely of regiments from a single state.”86 The Michigan Cavalry Brigade later was bolstered by the addition of a fourth from the Peninsula State, thus combining the First, Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Michigan horse regiments. Six months later, their special status was enhanced on the eve of Gettysburg. Promoted from captain to brigadier general, George A. Custer of Monroe, Michigan,87 was given command. The move was intended to instill élan in the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry command, which was often bested by Rebel cavalry.88 It succeeded wildly. Of Custer’s exploits there is no shortage of telling and, in the Civil War, most fell in the favorable column. Without those he commanded, of course, Custer would never have reached the apogee of his fame. They were “an elite unit,” the best brigade in the cavalry arm.89

A case in point is the encounter between the Michigan troopers and Jeb Stuart’s cavalry at Hunterstown, Pennsylvania, late in the day on July 2, 1863. The Union Third Cavalry division had been ordered to protect the Federal right flank near the town. Their advance scouts came into contact in the main street of Hunterstown with the rearguard of one of Stuart’s brigades commanded by Wade Hampton. Falling back, the Confederates regrouped near a farmhouse on the road to Gettysburg. Custer had been directed to engage the gray cavalry, and he ordered a company of the Sixth Michigan to charge the enemy. Almost immediately, he drew his sword and shouted to the surprised troopers, “I’ll lead you this time boys—Come on!”

Custer led the lone company southward past the Felty farm and directly into Hampton’s defenders near the Gilbert house. The Confederates were posted on both sides of the road, and the fighting was furious. In hand-to-hand combat, Custer’s horse fell, trapping the Boy General underneath. Rebels began to surround the dismounted and frantic officer. One approached Custer either to capture or kill the prize.

Twenty-three-year-old private Norvill Churchill of the First Michigan, one of the general’s orderlies, came to the rescue. Riding up, he shot the enemy soldier and reached down for his commander. Custer grabbed Churchill’s arm, pulled himself up and seated himself as best he could, hanging onto the saddle for dear life. Churchill turned his horse, and the three raced toward comrades and safety with the rest of Company A following close by. In the space of a few minutes, several Union soldiers had been killed or wounded, but the quick thinking of a young man from Almont90 had saved the new general and preserved him for action the next day, at East Cavalry Field at Gettysburg, and on many other fields of fire before war’s end.91 Churchill’s commanding officer, coincidentally, was also twenty-three.92

Custer and Stuart went at it again on the third day at Gettysburg. On the far left Confederate flank, Stuart brought his cavalry to harass and circle around behind the Union lines, sewing confusion in coordination with George Pickett’s charge at the Federal center. Interdicting him was a detached unit of the Union cavalry—Custer’s Michigan Brigade. The field east of Gettysburg saw numerous charges between the two forces, including several led by Custer himself. He rode to the head of one column and shouted, “Come on, you Wolverines!” Stuart was blocked and withdrew.93

Custer’s charmed life while cutting a conspicuous figure94 meant harrowing escapes on a number of occasions. Not so for Noah H. Ferry of the Fifth Michigan Cavalry. Born on Mackinac Island in 1831, he grew up in Grand Haven and entered the service as captain of Company F in August 1862. Promoted to major in December 1862, he coolly led troops at East Cavalry Field. His men revered him. While rallying his men, a Confederate bullet killed him instantly. His immediate commanding officer, Russell Alger, would write: “His death cast a deep gloom upon the entire Brigade. He was a gallant soldier, an exemplary man, and his loss was a great blow.” His father traveled to Gettysburg after the battle to retrieve the body of his brave son. He was buried in Lake Forest Cemetery in Grand Haven.95

Noah H. Ferry was born on Mackinac Island on August 30, 1831. He served in the Fifth Cavalry and was killed in action at East Cavalry Field, Gettysburg, on July 3, 1863.

The Michigan Cavalry Brigade would take fearfully high casualties during the Overland Campaign. In May 1864, its losses totaled 45 percent: of 1,700 men in the brigade, 98 would be killed in action, 330 wounded and 348 missing. At Trevilian Station in June, “[b]attling alone in dense, tangled underbrush, the Wolverines sustained 416 casualties, including 41 killed, the highest for the cavalry in the entire war.”96

In the western theater, the horsemen of Michigan wrote their own history. Perhaps the winner of the longest Civil War book title competition would be A Hundred Battles in the West: St. Louis to Atlanta, 1861–65. The Second Michigan Cavalry with the Armies of the Mississippi, Ohio, Kentucky and Cumberland, under Generals Halleck, Sherman, Pope, Rosecrans, Thomas and Others; with Mention of a Few of the Famous Regiments and Brigades of the West.97 The lengthy description aptly suggests how the Second Michigan Cavalry fought on many of the western battlegrounds. Rendezvousing at Grand Rapids in October 1861, the regiment fought at Island No. 10, in the campaign and siege of Corinth, at Perryville, at Chickamauga, at Knoxville, under Sherman into Georgia and under Thomas during the Nashville campaign.

The regiment should be renowned for another cause. One of its commanders was Philip A. Sheridan. The citizens of Port Huron presented a horse (one account indicates he was foaled near Grand Rapids) to Company K of the Second Cavalry, and the animal found its way into Sheridan’s possession. The three-year-old mount was presented by the officers to Sheridan, then colonel of the regiment, in the spring of 1862 when the regiment was stationed at Rienzi, Mississippi, and that is how he got his name. Over seventeen hands in height, powerfully built, he was one of the strongest horses that Sheridan ever had. And Rienzi was cool under fire.

At Cedar Creek in the fall of 1864, Sheridan made a ride aboard Rienzi that became the stuff of legend. Hearing the sound of battle many miles away from Winchester, Sheridan spurred the horse and raced toward the conflict. He encountered groups of dispirited Federals retreating along the road; waving his hat and shouting for them to turn around and fight, Sheridan—and Rienzi—helped turn the tide and deliver a smashing defeat to the Confederate forces in the Shenandoah Valley:

The distance from Winchester to Cedar Creek, on the north bank of which the Army of the Shenandoah lay encamped, is a little less than nineteen miles. As we debouched into the fields…the general would wave his hat to the men and point to the front, never lessening his speed as he pressed forward. It was enough. One glance at the eager face and familiar black horse and they knew him and, starting to their feet, they swung their caps around their heads and broke into cheers as he passed beyond them; and then gathering up their belongings started after him for the front, shouting to their comrades farther out in the fields, “Sheridan! Sheridan!” waving their hats and pointing after him as he dashed onward…So rapid had been our gait that nearly all of the escort save the commanding officer and a few of his best mounted men had been distanced, for they were more heavily weighted and ordinary troop horses could not live at such a pace.98

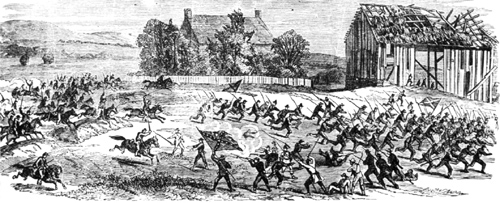

The “Gallant Charge” of the Sixth Cavalry near Falling Waters on July 14, 1863. The illustration is by Edwin Forbes, Harper’s Weekly.

Personal exploits on horseback were not the exclusive province of generals. After participating in the Corinth campaign in late 1862, Ransom Myers was wounded in a conflict in Kentucky, suffered an arm amputation and returned to Michigan. He was not yet finished. With one arm, he reenlisted in the Tenth Michigan Cavalry to serve as a courier. Though he could no longer easily fire a weapon, his disability did not mean he lacked the will to serve at the front. He was discharged at war’s end, becoming a minister of the gospel and serving in another army.

The Tenth Michigan Cavalry was in on the demise of John Hunt Morgan, the “Mosby of the West.” Morgan met his fate “at the hands of Tennessee Unionists—the Thirteenth and Ninth Tennessee Cavalry regiments, aided by the Tenth Michigan.” After the Confederate general’s escape from the Ohio Penitentiary, he began operating in east Tennessee and planned an attack on a brigade of Tennessee and Michigan troops near Knoxville. On September 3, 1864, he moved his troops to Greenville, the home of Vice President Andrew Johnson. Morgan went to sleep in town and was awakened during the night to find the Union troops he had planned to attack surrounding the house. This time, however, his escape went awry, and he was fatally shot. “The forces engaged on the Union side” were the Thirteenth and Eighth Tennessee and “Tenth Michigan, Major Newell” of Ypsilanti commanding.99

The Michigan adjutant general’s report tells the story:

The 10th Michigan Cavalry, then in command of Major Newell, encamped near Bulls’ Gap, is ordered by General Gillam to attack the enemy’s camp [along the Greenville road]. Marching all night, he dismounts his men at daylight and charges into Morgan’s first camp, driving the enemy in hot haste, leaving their breakfast half cooked, and their dead and wounded. Reaching the second camp, the enemy is found in better condition. General Gillam comes up with the 9th Tennessee Cavalry (Colonel Brownlow), orders that regiment to the charge with sabres, but a sharp fire from the enemy drove the regiment back. The 13th Tennessee Cavalry (Colonel Miller) comes up, the enemy driving the 9th advances rapidly, with a large cavalry force, at least 1,000 strong, filling the road from fence to fence. The 10th Michigan opens fire at about half pistol range with carbines, and soon the road is blocked with dead and wounded men and horses. The enemy, confused, hastily falls back, pursued to the woods, but is shelled out and pushes on to Greenville; is again charged on, becomes demoralized, breaks up, and flees. Morgan and staff are discovered under shelter of a house; a company of the 13th Tennessee is sent to capture him; he rushes for his horse, but is shot in the attempt by a sergeant of the company.100

Michigan not only participated in putting down the Mosby of the West, it was front and center in the end of Jeb Stuart out East. The Battle of Yellow Tavern was fought north of Richmond on May 11, 1864. The cavalry action resulted from Sheridan’s pursuit of Stuart, defending his capital, and whose aggressiveness led him to engage the Federals despite being greatly outnumbered. Sheridan went on the attack, and a little after four o’clock in the afternoon, in a driving rain, his troops charged the Confederate position, breaking it. Seeing the rift in his defenses, Stuart galloped to the fore and rallied his troops, driving off the Union troopers. One of those Union soldiers was Private John A. Huff of the Fifth Michigan, who had been a member of Berdan’s famed sharpshooters. With a single shot, Huff inflicted a mortal wound to Stuart’s side. “Stuart’s death befell in front of Custer’s Michigan brigade and it was a Michigan man who fired the fatal shot.”101

Hiram Berdan—his name symbolized the corps of expert marksmen he recruited who could inspire fear with their ability to hit faraway targets. With enlistments in the elite unit originating from many states including Michigan, the regiment played “a conspicuous part” at Chancellorsville in surrounding and capturing hundreds of prisoners of the Twenty-third Georgia and helping hold the center of the Union line when the day seemed lost. Berdan had lived in Plymouth, Michigan, from age six and “passed every leisure hour in the woods with his rifle”—“his rural Michigan background was ever reflected in his lifelong interest in the sport of target shooting.”102 From this unit came the marksman who ended Jeb Stuart’s life.

Not all of the general office cavalry casualties were on the Confederate side. Toward the end of the third day at Gettysburg, after Pickett’s charge had been repulsed, an action occurred beyond Big Round Top on the far Federal left flank. This time, it was twenty-five-year-old Elon J. Farnsworth, born in Michigan, who went to his fate:

It is remarkable that the most deliberate and desperate cavalry charge made during the Civil War passed so nearly unnoticed that the attention of the country was first drawn to it by reports of the enemy. The charge was directly ordered by General Meade and immediately after it was made he sent a congratulatory dispatch, and yet when the report went up that Farnsworth was killed and the regiment that he led all but annihilated, this order was withheld from the Official Report. The friends of Farnsworth attacked Kilpatrick for having ordered a wanton waste of life and he remained silent. If the charge had been on any other part of the field, or at an earlier hour of the day, it would have commanded wide attention. As it was, it was witnessed only by the enemy and by the few men at the batteries.

After the repulse of Pickett, Meade’s attention was drawn to an apparent movement of the enemy’s troops towards the right. His left wing was peculiarly unprotected. Law’s brigade was firmly lodged on the side of Round Top, and the valley to which Longstreet’s eye turned so eagerly was open. An order reached Kilpatrick to hurl his cavalry on the rear of Law’s brigade and create so strong a diversion that Lee’s plan would be disclosed.

There was an oppressive stillness after the day’s excitement. I rode to the front and found General Kilpatrick standing by his horse. He showed great impatience and eagerness for orders. The great opportunity, which was to have hurled his two brigades across the open fields upon the right and rear of Pickett’s broken columns had been allowed to pass. As I turned away an orderly dashed by shouting: “We turned the charge, nine acres of prisoners.” In a moment an aide came down and Kilpatrick sprang into his saddle and rode towards him. The verbal order I heard delivered was: “Hood’s division is turning our left; play all your guns; charge in their rear; create a strong diversion.”

In a moment, Farnsworth rode up. Kilpatrick impetuously repeated the order. Farnsworth, who was a tall man with military bearing, received the order in silence. It was repeated. Farnsworth spoke with emotion: “General, do you mean it? Shall I throw my handful of men over rough ground, through timber, against a brigade of infantry?”

We rode out in columns of fours with drawn sabres. After giving the order to me, General Farnsworth took his place at the head of the 3rd Battalion.

The 3rd Battalion under Major (William) Wells, a young officer who bore a charmed life and was destined to pass through many daring encounters…moved out in splendid form to the left of the 1st Battalion, and swept in a great circle to the right around the front of the hill and across our path, then guiding to the left across the valley and up the side of the hill at the base of Round Top. Upon this hill was a field enclosed with heavy stone walls. They charged along the wall and between it and the mountain directly in the rear of several Confederate regiments in position and between them and the 4th Alabama. It was a swift…charge over rocks, through timber, under close enfilading fire. The rush was the war of a hurricane. The direction towards Devil’s Den. At the foot of the declivity the column turned left, rode close to a battery, receiving the fire of its support, and swept across the open field and upon the rear of the Texas skirmish line. Farnsworth’s horse had fallen; a trooper sprang from the saddle, gave the General his horse and escaped on foot. Captain Cushman and a few others with Farnsworth turned back. The 1st Battalion was again in motion. The enemy’s sharpshooters appeared in the rocks above us and opened fire. We rode obliquely up the hill in the direction of Wells, then wheeling to the left between the picket line and the wall. From this point, part of my men turned back with prisoners. The head of the column leapt the wall, into the open field. Farnsworth, seeing the horsemen, raised his sabre and charged as if with an army. At almost the same moment his followers and what remained of the 1st Battalion cut their way through the 15th Alabama, which was wheeling into position at a run and offered little resistance. We charged in the same direction but on opposite sides of the wall that parallels Round Top and within two hundred paces of each other.

General Farnsworth fell in the enemy’s lines with his sabre raised, dead with five wounds, and received a tribute for gallantry from the enemy that his superiors refused. There was no encouragement of on looking armies, no cheer, no bravado. There was consecration and each man felt as he tightened his sabre belt that he was summoned to a ride of death.103

Merritt Lewis, Seventh Cavalry (Grand Rapids), lost his right leg at Gettysburg.

In the years after the war, artist and painter James Kelly successfully persuaded veteran officers to sit for sketches, portraits and small talk. One participant was General Alexander Pennington, who spoke of Custer with the familiarity of one who had seen him up close. Pennington recounted how an officer regarded the flamboyant Boy General as a “popinjay,” until seeing his courage in battle: “My God, I’ve had enough of him!” Pennington described Custer as being possessed of “a boyish chuckle. I never heard him laugh heartily,” and how he would carry “a canteen of cold tea on his saddle.” Finally, he told of how Custer’s horse ran away down Pennsylvania Avenue during the grand review, thanks to its pedigree in racing, the rider “looking like a blaze of glory.”104

Equally so, the Michigan horsemen, sharpshooters and engineers blazed their names and units into glory.