On the heels of the Army of the Potomac’s disaster on the Rappahannock in December 1862, Confederate president Jefferson Davis felt confident in making a prediction:

Out of this victory is to come that dissatisfaction in the North West which will rive the power of that section; and thus we see in the future the dawn—first separation of the North West from the Eastern States, the discord among them which will paralyze the power of both,—then for us future peace and prosperity.105

Davis’s reference to the “North West” subsumed Michigan. Would it grow dissatisfied after so many disappointments and follow the South’s example, withdrawing from support of the war during 1863?

In May, Lee again defeated the Army of the Potomac in the Battle of Chancellorsville. It was perhaps his most spectacular victory, and the hopes of the North for a change of outcome in the eastern theater were again dashed. On the heels of his victory, Lee launched his second invasion of the North in late June. En route to head off the Rebels, the Army of the Potomac got shocking news that a new commander would have to lead it into battle. The tides of war seemed all in Lee’s favor.

The Union defenders caught up to Lee outside of a crossroads town in southern Pennsylvania. Outnumbered by brigades of Confederate infantry, Buford’s troopers held them off early in the morning along the Chambersburg pike northwest of the village. Arriving infantry were thrown into battle as soon as they neared the field. Among them was the Twenty-fourth Michigan, the most recent addition to the Iron Brigade comprised of western regiments.

The moment was critical:

At an early hour on the 1st day of July we marched in the direction of Gettysburg, distant six or seven miles. The report of artillery was soon heard in the direction of this place, which indicated that our cavalry had already engaged the enemy. Our pace was considerably quickened, and about 9 A.M. we came near the town of Gettysburg, and filed off to the left…and were moved forward into line of battle on the double-quick…The brigade was ordered to advance at once, no order being given or time allowed for loading our guns…The order to charge was now given, and the brigade dashed up and over the hill, and down into the ravine through which flows Willoughby’s Run, where we captured a large number of prisoners…In this affair the 24th Michigan occupied the extreme left of the brigade…The brigade…marched into the woods known as McPherson’s woods, and formed in line of battle…the position was ordered to be held, and must be held at all hazards. The enemy advanced in two lines of battle, their right extending beyond and overlapping our left…The 19th Indiana, on our left,…was forced back. The left of my regiment was now exposed to an enfilading and cross fire, and orders were given for this portion of the line to swing back so as to face the enemy now on the flank…We made a desperate resistance; but the enemy accumulating in our front, and our losses being very great, we were forced to fall back…By this time the ranks were so decimated that scarcely a fourth of the force taken into action could be rallied…We had inflicted severe loss on the enemy, but their numbers were so overpowering and our own losses had been so great that we were unable to maintain our position, and were forced back, step by step, contesting every foot of the ground to the barricade.106

This account was written by the regiment’s colonel, Henry Morrow of Detroit. He had been wounded in the action, captured and released after the battle. He wrote of the losses being severe, which was no exaggeration. The regiment went into battle with 496 officers and enlisted men. It suffered 363 casualties; color bearers Charles Ballou, August Ernest, William Kelly and Abel Peck were killed, along with 8 officers: Gilbert Dickey of Detroit, Newell Grace of Detroit, Reuben Humphreyville of Livonia, Malachi O’Donnell of Detroit, Winfield Safford of Plymouth, Lucius Shattuck of Plymouth, William Speed of Detroit and Walter Wallace of Brownstown. The next morning, only 99 men answered roll call.107

Abel G. Peck, Twenty-fourth Infantry (Nankin), enlisted at age forty-two on August 6, 1862, as a color bearer. He was killed in action at McPherson’s Woods on the first day of Gettysburg.

The Twenty-fourth had bought time—time for the rest of the army to come up and time for those who followed to take heights south of Gettysburg and hold them on this first day of July against further Rebel attacks. The First Michigan Infantry reached the battlefield after midnight, having ruined their shoe leather at a furious pace. Initially held in reserve the next morning, it was directed to the front line around four o’clock in the afternoon and posted in a wheat field on the left flank between an elevation known as Little Round Top and the center along Cemetery Ridge. It numbered 20 officers and 125 soldiers. Their arrival was just in time:

We had no sooner got our line fully established than the enemy drove in our skirmishers and appeared in force in the edge of a wood on our front, within two hundred yards of our line. We ordered our men to fix bayonets, and commenced firing on the enemy with a deadly effect, driving him back with great loss. He, however, soon returned, and was a second time driven back with great loss. Our men stood up bravely under the storm of bullets sent against them, loading and firing as coolly as though on drill…We maintained our line, repulsing and holding in check the enemy until 7:30 P.M., when we were ordered to fall back, which we did in good order.108

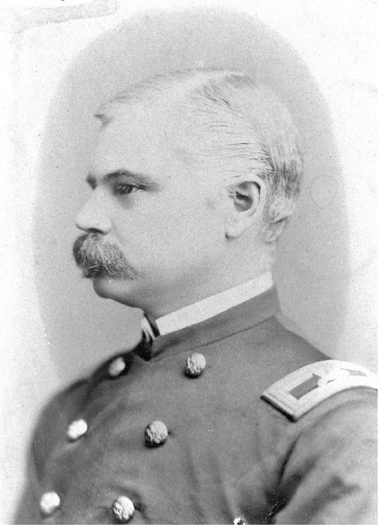

First Lieutenant John Pulford, Company A, Fifth Infantry, rose to brevet brigadier general for meritorious service.

Similar contributions were made at this location and in a nearby peach orchard by the 3rd, 4th and 5th Infantry. Colonel Harrison Jefferds of Dexter defended the flag of the 4th in hand-to-hand fighting and paid for it with his life. The 5th was noted in the brigade after-action report: “The unflinching bravery of the 5th Michigan, which sustained a loss of more than one-half of its numbers without yielding a foot of ground, deserves to be especially mentioned.”109 Its colonel, John Pulford of Detroit, suffered two wounds in the fighting.110

Little Round Top commanded the Union line, which stretched out from its northern slope onto a ridge near the town cemetery. Confederate forces had noted the hill’s strategic position and mounted a strong force to take it on this second day. A brigade composed of a regiment each from New York and Pennsylvania, the Twentieth Maine and the Sixteenth Michigan were rushed to the top. Arriving “in the nick of time” just before the Rebels, the brigade quickly piled stones together from which to begin firing at the gray soldiers climbing toward them. The Sixteenth faced into the teeth of an assault from a legendary Texas brigade and, when ammunition supplies failed, they used rocks against the enemy: “It was a deadly strife, with hand to hand encounters, clashing bayonets, clubbed muskets, and rough stones dug in desperation from the face of the rough hillside.”111 Desperation led to a charge down the hill that, against the odds, drove the Confederates off. The hill remained in Union hands for the rest of the battle.

On the afternoon of July 3, the Seventh Michigan Infantry was posted at the very center of the Union line near a low stone wall and a small wood of trees. The men had marched nearly seventy-five miles in three days and fought the day before in support of their comrades at the Wheatfield and the Peach Orchard. Its complement was down to 14 officers and 151 men out of the original 900. The men had stacked rails, stones and earth in front of their line for protection, using sticks and boards as implements in the absence of shovels. Posted on low-slung Cemetery Ridge, it had a front-row seat for what might develop during the afternoon.

Around 1:00 p.m., over one hundred Confederate artillery pieces opened up on the position held by the Seventh and its brigade in an obvious attempt to prepare the way for a major assault. Fortunately, the enemy gunners miscalculated a bit, and their shells landed primarily to the rear of the Union front-line position. At 3:00 p.m., the firing ceased, and thousands of Confederate infantry began to march out from under the protection of trees, form up in parade ground fashion and start off across the intervening farm fields to assault the Federal position. They came in several lines—waves, as it were. These were the troops who had been victors on the Peninsula, at the two Manassas battles, at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. Watching as they marched to the attack was its mastermind, Robert E. Lee, who had again and again correctly calculated how to impose defeat on his adversary.

Opposing the oncoming Rebel force was a line of blue infantry that included the Seventh. Federal artillery commander Henry Hunt sought to aid their defense and now brought a hundred Union guns to bear on the Rebel charge. Hunt seemed to be everywhere this fateful day. At midmorning, he had carefully inspected the entire line in the center to verify that all the Federal batteries were in good condition and fully supplied. His instructions to the batteries and chiefs of artillery were to fire their guns deliberately and concentrate it on one enemy battery at a time—not stopping until each was silenced. Hunt was on the summit of Little Round Top at 1:00 p.m., when the Confederate guns opened up at the center. He had immediately left for the Artillery Reserve park to order all replacement batteries prepared to move up at a moment’s notice. Next he had proceeded along the line, under fire, to replace batteries that were disabled by the Confederate barrage. About 2:30 p.m., he ordered his gunners to gradually cease their return fire to conserve ammunition for the infantry charge he expected to come and, in the process, perhaps deluded the Confederates that the cannonade had silenced enough Union guns to justify advancing their infantry. At 3:00 p.m., as the enemy infantry advanced, he ordered new batteries into position to replace exhausted ones and positioned guns to operate both in front and in flank of the oncoming wave. As he waited for their arrival near the stone wall, Hunt sat on his horse and drew his sidearm, ready to help repel the thousands of soldiers who were approaching the Federal line.

The brigade commander of the Seventh was Norman Hall, and here is what he would write afterward of the next several moments:

My line was single, the only support…having been called away…There was a disposition in the men to reserve their fire for close quarters, but when I observed the movement the enemy was endeavoring to execute, I caused the Seventh Michigan and Twentieth Massachusetts Volunteers to open fire at about 200 yards. The deadly aim of the former regiment was attested by the line of slain within its range. This had a great effect upon the result, for it caused the enemy to move rapidly at one point and consequently to crowd in front—being occasioned at the point where his column was forming, he did not recover from this disorder.

There was but a moment of doubtful contest in front of the position of this brigade. The enemy halted to deliver his fire, wavered, and fled, while the line of the fallen perfectly marked the limit of his advance. The troops were pouring into the ranks of the fleeing enemy that rapid and accurate fire, the delivery of which victorious lines always so much enjoy, when I saw that a portion of the line…on my right had given way, and many men were making to the rear as fast as possible, while the enemy was pouring over the rails that had been a slight cover for the troops.

Having gained this apparent advantage, the enemy seemed to turn again and re-engage my whole line…I was forced to order my own brigade back from the line, and move it by the flank under a heavy fire. The enemy was rapidly gaining a foothold; organization was mostly lost; in the confusion commands were useless, while a disposition on the part of the men to fall back apace or two each time to load, gave the line a retiring direction. With the officers of my staff and a few others, who seemed to comprehend what was required, the head of the line, still slowly moving by the flank, was crowded closer to the enemy and the men obliged to load in their places. I did not see any man of my command who appeared disposed to run away.

The line remained in this way for about ten minutes, rather giving way than advancing, when, by a simultaneous effort upon the part of all the officers I could instruct, aided by the general advance of many of the colors, the line closed with the enemy, and, after a few minutes of desperate, often hand-to-hand fighting, the crowd—for such had become that part of the enemy’s column that had passed the fence—threw down their arms and were taken prisoners of war, while the remainder broke and fled in great disorder…Generals Garnett and Armistead were picked up near this point, together with many colonels and officers of other grades.

Twenty battle-flags were captured in a space of 100 yards square…Between 1,500 and 2,000 prisoners were captured at the point of attack…Piles of dead and thousands of wounded upon both sides attested the desperation of assailants and defenders.112

Among the dead was the Seventh’s lieutenant colonel, Amos Steele of Mason, killed while leading his men to defeat the assault.113

The battle—and perhaps the war—had hung in the balance. Michigander Hall, veteran of so many actions, evaluated what had happened:

In claiming for my brigade and a few other troops the turning point of the battle of July 3, I do not forget how liable inferior commanders are to regard only what takes place in their own front, or how extended a view it must require to judge of the relative importance of different points of the line of battle. The decision of the rebel commander was upon that point; the concentration of artillery fire was upon that point; the din of battle developed in a column of attack upon that point; the greatest effort and greatest carnage was at that point; and the victory was at that point.114

“At that point.” Here it was that a “rain of missiles,” a “terror-spreading” barrage, had been concentrated on their position. Here it was that the gray infantry marched forward with “an appearance of being fearfully irresistible.”115 Here it was that near the stone wall, behind a rail fence, the Seventh Michigan stood against the irresistible at the very moment when the battle would turn. Ever after, this point would be known, and commemorated by monument and memory, as the “High Water Mark of the Confederacy.”

Michigan cavalry also played a part in the victory on the third day. On the far right of the Union positions, the cavalry brigade under the command of General George Custer met the mounted legions of Wade Hampton, right-hand to Jeb Stuart. The Boy General and his Michigan riders “charged in close column upon Hampton’s brigade, using the saber only, and driving the enemy from the field.”116 On the left, the other cavalry boy general from Michigan, Elon Farnsworth of Green Oak Township, made a desperate charge that cost him his life.117

July was also an important month in the other theater of war. The day after the battle at Gettysburg concluded, Grant’s campaign to take the Confederate stronghold at Vicksburg, Mississippi, concluded with the surrender of the town and thirty thousand defenders. For weeks the Union army had marched through Mississippi, defeating each Rebel contingent it confronted, until finally trapping the Confederates and laying siege to the river town. Michigan troops were in the campaign and helped capture Vicksburg, closing off the Mississippi River to Confederate navigation for the remainder of the war. The Second, Sixth, Eighth, Twelfth, Fifteenth, Twentieth and Twenty-seventh Infantry Regiments had marched, fought and assaulted the Rebels until achieving victory in the surrender on the Fourth of July.

While eyes back home were glued to the reports emerging from Gettysburg and Vicksburg, the Twenty-fifth Michigan Infantry was trying to save Louisville, Kentucky. Recruited from towns like Buchanan, Galesburg, Holland, Niles and Three Rivers, five companies were defending a bridge across the Green River at Tebbs Bend on the morning of July 4. Confederate cavalry commanded by General John H. Morgan outnumbered them four to one. He ordered the regiment to surrender—the cause of the 260 Michigan troops was hopeless. Colonel Orlando Moore of Schoolcraft replied, “This being the Fourth of July, I cannot entertain the proposition of surrender.” Morgan made eight attacks on their entrenchments. At the medical station, treating the wounded, a surgeon discovered something unusual about his patient: she was Lizzie Compton, a woman disguised as a man in order to fight for her country. Her services under fire helped turn Morgan away and produce an unlikely victory.

Lorin L. Comstock (Adrian), served in the First Infantry (three months) and as a lieutenant colonel of the Seventeenth Infantry. He died on November 25, 1863, after being hit with a musket ball by a Rebel sharpshooter at Knoxville.

In the fall, the Federal force at Knoxville found itself under siege. Among their number was Charles Howard Gardner, a Michigan boy serving as drummer in his unit. Gardner had grown up in Flint; when Charley was thirteen, his father joined the Second Michigan Infantry, and his favorite teacher, S.C. Guild, signed up with the Eighth. Charley enlisted with his teacher’s unit as part of its band. He was, after all, too young to fight. The outcome of their volunteering would be the same. Charley’s father died while in service of typhoid fever; Guild was killed in action. The young Gardner decided not to quit and remained with his regiment during the siege in Knoxville. During action he was shot, but the wound did not initially appear fatal. After the siege was lifted and the Eighth had fought off the Rebels, the wounded Charley Gardner was sent back to Detroit for recuperation. He never made it. His mother and siblings, anxiously awaiting a happy return after losing the other two, would have to learn of Gardner’s death en route.

Charles H. Gardner, musician, Eighth Infantry (Flint), enlisted for three years at age fourteen. He died December 21, 1863, at Knoxville from wounds received on December 1.

After Grant’s great victory at Vicksburg, he was assigned to replace Rosecrans at Chattanooga when the latter let himself get entrapped at that Tennessee River town. The first step Grant took was to open up a solid supply line, for the Union troops were on short rations. Michigan engineers built a magnificent bridge over the river as a key part of eliminating the shortage. Hemming in the besieged Union army, the Rebels sat atop a naturally strong position of Lookout Mountain on the west and Missionary Ridge to the south. The Rebel commander, Braxton Bragg, thought his position was impregnable.118 On Saturday, November 25, his troops fully supplied, Grant launched attacks on both wings of the Confederate position. After the passage of several hours, neither was succeeding, so in late afternoon, he directed an assault on the center, hoping to draw defenders away from their flanks and make those attacks victorious. What happened next surprised even the unflappable Grant.119

The Eleventh Michigan, under the command of William Stoughton of Sturgis,120 was posted in the Union center, to the left of troops commanded by Philip Sheridan. They faced an open field of nearly a half-mile’s length in front of Missionary Ridge. Rebel rifle pits were located halfway up the slope, and a strong breastwork with cannons in place here and there was visible at the top. Bragg’s confidence did seem well placed. Receiving Grant’s order to attack, the regiment and the whole line in the center moved forward toward this “impregnable mountain wall that blotted out half the sky.”121 The advance was immediately shelled by Confederate artillery, but they continued to move steadily toward the base of the hill and a line of pickets. The thin gray line was sent fleeing up the hill, but this was little achievement. The Rebel fire upon their position at the base was growing ever more destructive, so Stoughton ordered a charge up the slope upon the first line of rifle pits. Scrambling up the side of the ridge, the Union infantry took the position and regrouped during a brief respite. They soon discovered it was no place to stay—the “rising slope was an obvious deathtrap…From the crest of the ridge the Confederates were sending down a sharp plunging fire.”122

Another order was given: “At the command the whole line sprung forward in gallant style and moved rapidly up the steep and difficult ascent. When near the crest they dashed forward with a shout of victory, routing the enemy and driving him from his stronghold, and capturing a large number of prisoners and one piece of artillery.”123

The Eleventh had done what seemed impossible. Marching across an open plain in full sight of the enemy, undergoing artillery fire all the while, taking the picket line at the base, then the rifle pits halfway up and then assaulting the breastworks on the summit, they had gone into battle with 255 officers and men, suffered 34 casualties and won for their command—and Grant, who would soon be sent East—a great victory.

Albert Sonewald, First Infantry (Ann Arbor), was a veteran of battles from Mechanicsville to Gettysburg. He died of disease in a Washington, D.C. hospital on October 31, 1863.

As the year was ending, the voters of Troy Township went to the polls on December 28 to decide whether to approve a new tax. Proceeds would be used to encourage enlistments by paying $100 to each man who volunteered to join the Union military. The bounty was one of many proposed to Michigan voters in local and state elections to encourage enlistment. In the midst of the war, the people of this community had to confront imposing higher taxes on themselves in order to send more soldiers off on behalf of the Union. Troy voters said “yes.”

Jefferson Davis had proven a poor prophet. How would the record be written of Michigan’s participation during 1863?

They bore a conspicuous and gallant part in the ever memorable campaigns under General Hooker in Virginia, and General Meade in Pennsylvania, at the defense of Knoxville by General Burnside, at the capture of Vicksburg by General Grant, and on the celebrated Kilpatrick raid against Richmond. They were also engaged in the campaign of General Rosecrans against Chattanooga.124

Employing neutral terms like “conspicuous” and “memorable” suggested mixed results; “gallant” left nothing to judgment. In truth, this summary far understated the sacrifices and valor contributed during this year by Michigan’s infantry, cavalry, artillery soldiers and citizens back home.