In June 1967, urban violence erupted in Michigan’s largest city after a police raid on a blind pig backfired. It was a hot summer, the war in Vietnam was raging and racial tensions between the African American community and the police department boiled over. In June 1943, a civil disturbance erupted in Detroit when violence broke out between racial groups. Social and migration changes caused by World War II set teeth on edge. Both riots had a Civil War antecedent, reflecting unfinished business about race.

On March 6, 1863, after the trial of a “colored” man resulted in conviction for assaulting a white female, rioters—dissatisfied with the resulting jail sentence—took to Detroit streets to inflict injury on persons and property. No draft riot like the infamous New York City event of July 1863, it was, by all accounts, racially driven.125 The media contributed to the discord: the Detroit Advertiser & Tribune blamed the event on racially oriented coverage by its competitor, the Detroit Free Press; for its part, the Free Press blamed the event on those who were disrupting the existing social order.126 At the same time whites in Detroit were inflicting death and destruction on blacks, in Lansing, the governor of Michigan was calling for more racial equality and equal rights. A civil war seemed to be raging within the state over the issue of freedom: for whom and under what conditions?

About 45,000 people lived in Detroit according to the 1860 census. Some 6,799 blacks were recorded in Michigan that year, with a quarter of their population residing in Detroit. On April 25, 1861, reacting to Fort Sumter and mobilization of troops to answer Lincoln’s call, black Detroiters met at the Second Baptist Church to declare:

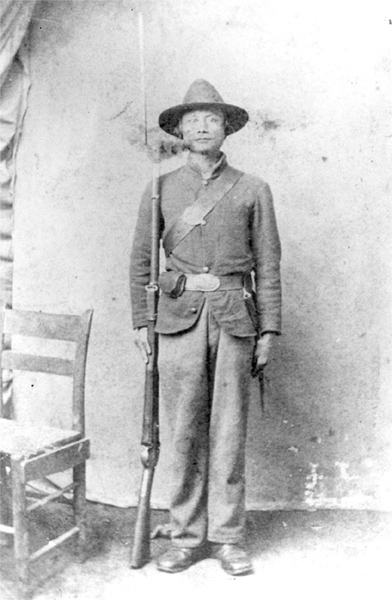

Felix C. Balderry, Eleventh Infantry (Leonidas Township), enlisted at age twenty-one on December 7, 1863, for three years. A “South Sea Islands immigrant,” he was most likely Filipino.

1. That we love this land of our nativity, above all lands.

2. That when the government of the State of Michigan manifests a deposition to recognize us as men and citizens,…then we will sacrifice our lives, if necessary, in defense of the flag of our country.

3. That…as men whose hearts are with the union and the flag, we beg the government of Michigan to place us in such a position that we may be able to prove the courage, devotion and patriotism of our people.

4. Nevertheless, that if the State of Michigan is ever invaded we hold ourselves ready and willing, in common with other men to repel such invasion at all hazards and to the last extremity.127

African Americans elsewhere in Michigan made similar offers.128

Such volunteerism could not be accepted under Federal law. The second Militia Act of 1792 made eligible for service “each and every free able-bodied white male citizen” of a state. Lincoln’s call for three-months’ soldiers, invoking this statutory authority, could not lawfully enable nonwhites to fight the Southern rebellion. The lengthening course of the war, however, made necessary a reappraisal of this policy.

In Michigan, the campaign to advocate reversal of this policy began early. Governor Blair supported black enlistment and emancipation. The Detroit Advertiser & Tribune called for the enlistment of blacks, given their obvious “ability to serve in a [sic] intelligent and courageous manner.”129 People of color in Detroit were “especially vocal”130 in support of such a step. Michigan’s two U.S. senators, Zachariah Chandler and Jacob Howard, were on the side of such efforts in Congress. A revised militia act, passed with their support in July 1862, permitted enlistment “for the purpose of constructing intrenchments [sic], or performing camp service or any other labor, or any military or naval service for which they may be found competent, persons of African descent.”

Such service merited reward:

Any man or boy of African descent, who by the laws of any State shall owe service or labor to any person who, during the present rebellion, has levied war or has borne arms against the United States, or adhered to their enemies by giving them aid and comfort, shall render any such service as is provided for in this act, he, his mother and his wife and children, shall forever thereafter be free, any law, usage, or custom whatsoever to the contrary notwithstanding.

When the vote for the bill came up in the summer of 1862, both senators were steadfast in seeking the maximum opportunity for blacks to serve in the military.131

In the spring of 1863, not content to limit duties to support roles, Governor Blair and Senator Chandler jointly applied to the War Department for authority to raise a regiment of colored infantry. Advertiser & Tribune editor Henry Barnes separately wrote for permission. They would have to wait until July for the War Department to issue approval—but once received, little more delay occurred. Within just a couple of weeks, Adjutant General Robertson authorized Barnes to begin enrollment in the first Michigan regiment of persons of color. The choice of a newspaperman to lead the effort, and his commissioning as colonel of the regiment, meant that someone with no military experience would initially lead the Michigan contingent.

Kinchen Artis, Company H, First Colored Infantry, enlisted at age thirty-seven on December 19, 1863, at Battle Creek for three years.

Six months later, on February 17, 1864, the First Michigan Colored Regiment mustered, 895 strong, and marched down Woodward Avenue to the approbation of onlookers. It had taken a while to achieve the requisite strength—not because of a lack of fortitude by Michigan blacks, but because their ranks had been reduced by bounties (army pay was lower than that of whites) and recruiting efforts from other northern states that lacked a significant African American population. To prevent the undermining of Michigan’s contribution, the legislature acted to prohibit recruiting of Michigan men by out-of-state interlopers. In December 1863, the regimental leadership and band made a tour of the southern Michigan counties, stopping in Ypsilanti, Ann Arbor, Jackson, Niles, Cassopolis, Marshall and Kalamazoo. Traveling the circuit paid off, doubling the number of enlistments in just a few weeks.

After their mustering in, the regiment trained at Camp Ward just east of downtown Detroit.132 In March, they embarked for Annapolis and further training. After arrival, Barnes resigned as colonel and returned to Detroit, with his mission to deploy black soldiers in the field accomplished. Detroiter Henry L. Chipman, a regular army captain at war’s inception and an officer of high regard, was promoted from lieutenant colonel. The unit was transported to Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, in April and, on May 23, 1864, was redesignated as the 102nd United States Colored Troops (USCT) in accordance with War Department requirements.

As was typical with USCTs, the Michigan unit initially was assigned guard duty, rather than front-line service, of fortifications on the island and in Beaufort. In early August, they moved to Jacksonville, Florida, and first “saw the elephant.” On August 11, a march inland to the village of Baldwin was met by a troop of Confederate cavalry seeking to protect the rail junction. The rebels attacked—and were repulsed by the 102nd. This first successful encounter was followed up by a five-day, one-hundred-mile march farther into Florida, tearing up track and destroying rolling stock. Their route passed the battleground at Olustee where, just months earlier, a Union force had been defeated. If accounts of that conflict were accurate, casualties in the black troops involved had included post-battle hostilities.

At the end of August, the regiment was transferred back to Beaufort. On November 28, it was part of an expeditionary force that steamed up the Broad River to sever the Charleston & Savannah Railroad near Pocotaligo, South Carolina, and support Sherman’s campaign against Savannah. Disembarking at Boyd’s Landing, it marched inland and, on November 30, encountered an entrenched Confederate force at Honey Hill. During the battle, a section of the 3rd New York Artillery was cut down by Southern fire, jeopardizing its ordnance. The 102nd was ordered to secure and bring off the cannons. After an initial attempt did not succeed, an officer and thirty men thrice rushed forward to secure the guns where Rebel artillery and sharpshooters had killed off the gunners. Each rush retrieved an artillery piece. Their commander was later awarded the Medal of Honor and, in his after-action report, Colonel Chipman wrote: “Too high praise cannot be awarded to Lieutenant [Orson] Bennett133 for the gallant manner in which he led his men in that perilous enterprise, nor to his men who so faithfully followed their leader.” With one-fifth of the force suffering casualties—sixty-six in total—the heroism of these men could not be argued.134

In January, the regiment again began a campaign to support Sherman’s march northward. The men made several expeditions into the countryside, attacking and dispelling Confederate cavalry and destroying railroads. On February 27, they entered the captured city of Charleston, having “ransacked every plantation on our way and burnt up every thing we could not carry away.”135 An early March expedition found them moving toward Georgetown, then turning toward the heartland, to begin destruction of rail lines and equipment through Sumter(ville) and Camden. After taking the latter town, the force marched south toward Stateburg until, on April 18, meeting Confederates where Swift Creek ran into the Wateree River at Boykin’s Mill. The Rebel force was across the creek and on higher ground, with marshes protecting the approaches. Several unsuccessful assaults were made until the 102nd was ordered to flank the Confederates on their right; with “the aid of a negro guide they succeeded in crossing on a log.” Having a lodgment to turn the Rebel line, the entire force then charged their position and succeeded when “the enemy gave way.” The next day saw the same kind of encounter at Rafting Creek, and the same flanking tactic was employed to the same level of success. Driving the Rebs off, the force resumed its march back toward Georgetown and further warfare.

It was no longer necessary. On April 21, during a midday rest stop at Fultons Post Office south of Manchester, a detachment of Confederates appeared, bearing a flag of truce. The Southerners conveyed the imminent surrender of Joseph Johnston to Sherman. With Lee having capitulated in Virginia, no other major Confederate force was in the field east of the Mississippi—thus, the war was effectively over. The expedition had been a success, with minimal losses. Chipman was recognized for “excellent service” thanks to the performance of his troops.136 The regiment spent the next five months in Charleston on occupation duty.

Flag of the First Colored Infantry.

On September 30, 1865, the 102nd USCT ceased to exist when the veterans were mustered out of Federal service. They returned to Detroit, arriving on October 17 and 19. A total of 1,555 had enlisted and, according to U.S. provost marshal records, 1,387 men served in the unit. Approximately 150 deserted, a typical attrition rate during the war, with a desertion rate of only 1.2 percent in the field. About 10 percent never came home: 6 were killed in action, 5 died of wounds and 129 died of disease. Their average age was 25.8; some were younger than 18. Approximately 43 percent were farmers, because a full two-thirds had come from southwest Michigan, while 9 percent were from Detroit. Very few had been born in Michigan, for obvious reasons, but they did the state proud. Even the Free Press conceded that they had fought nobly.

Inspired by their service, fellow Michigander Sojourner Truth is credited with authoring lyrics of “The Valiant Soldiers,” sung to the tune of “John Brown’s Body.”137 Modern-era Detroiter Dudley Randall wrote this springtime poem in the honor of the soldiers of the 102nd:

Memorial Wreath

In the green month when resurrected flowers

Like laughing children ignorant of death,

Brighten the couch of those who wake no more,

Love and remembrance blossom in our hearts,

For you who bore the extreme sharp pang for us,

And bought our freedom with your lives.

And now,

Honoring your memory, with love we bring

These fiery roses, white-hot cotton flowers

And violets bluer than cool northern skies

You dreamed of stooped in burning prison fields

When liberty was only a faint north star,

Not a bright flower planted by your hands

Reaching up hardy nourished with your blood.

Fit gravefellows you are for Douglass, Brown,

Turner and Truth and Tubman…whose rapt eyes

Fashioned a new world in this wilderness.

American earth is richer for your bones;

Our hearts prouder for the blood we inherit.