Son of the Morning Star, Yellow Hair, Boy General: most Americans recognize one of Michigan’s most famous military officers by such terms, for they refer to George Armstrong Custer of Little Big Horn fame. More than a decade before that encounter, Custer led the Michigan Cavalry Brigade to glory after his promotion from captain to brigadier general138 on June 28, 1863, immediately before the Battle of Gettysburg. He was but one of three elevated that day. Wesley Merritt of New York was also promoted to brigadier general from captain; he went on to division command under Phil Sheridan. Custer and Merritt remain well known, the former for the fateful day in the Black Hills of South Dakota, the latter for, among other things, presiding over the inquiry into that event. What of the third appointee?

Elon John Farnsworth was born on July 30, 1837, in Green Oak Township, Michigan. He entered the University of Michigan in 1855 but left in 1858 to join the First Dragoons in the Mormon conflict in Utah. After the Civil War began, he led a cavalry regiment in a number of eastern theater engagements. On the road to Gettysburg, the cavalry commander of the Army of the Potomac recommended his promotion to brigadier general and command of the First Cavalry Brigade, Third Division. He led his troopers into action at Hanover Station on June 30, driving off Jeb Stuart’s horsemen. At an action on July 1 en route to Gettysburg, Farnsworth was slightly wounded but remained in the saddle. The next day, after dark, brought on another skirmish at Hunterstown; then came the third day of the battle.

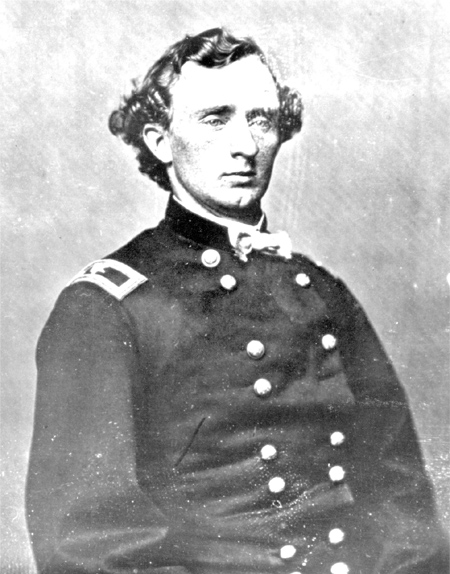

George A. Custer, before fame.

Pickett’s Charge at the center of the Union line had just failed, and the Army of Northern Virginia drew itself up to defend against a counterattack. Union commander Meade decided not to risk wide-scale offensive action. On the Federal left, however, Farnsworth was ordered by his immediate superior, General Judson Kilpatrick (nicknamed “Kill Cavalry”), to attack the Confederates’ far right flank in coordination with Merritt’s force.

Although Farnsworth protested that it was suicide, Kilpatrick insisted that he should charge with half of his brigade against the center of Law’s slender line. Law by juggling his men about had neutralized Merritt’s threat and had shifted what little weight he could spare against Farnsworth, who soon found himself running through a gauntlet of Confederate infantry no matter which way he turned. He put on a brilliant display of courage and horsemanship, but the attack ended in a fiasco, including the death of Farnsworth.139

The “gallant Farnsworth fell, heroically leading a charge of his brigade, against the rebel infantry,” suffering “five mortal wounds.”140 The site where he went down, known today as South Cavalry Field, is a section of America’s most famous battlefield that is least visited. Farnsworth was twenty-five years old and had been a general officer for six days.

Another Michigan-bred general fought with distinction at Gettysburg. Henry J. Hunt was born to a military family at Detroit Barracks on September 14, 1819,141 and spent part of his adolescence in Maumee, just across the Ohio border. His appointment to West Point ended with a ranking in the middle of the class (nineteenth of thirty-one).142 Serving in the Mexican War and the Mormon expedition, Hunt possessed extensive combat and leadership experience when the Civil War began. His battery covered the retreat at First Bull Run, and he was the tactical genius behind the massed batteries of Federal artillery that decimated Rebel attacks at Malvern Hill, saving the Army of the Potomac. Such contributions were echoed at Antietam and Fredericksburg; notwithstanding, under General Joseph Hooker, his command was reduced to a nominal level at the Battle of Chancellorsville, which Hunt argued, and Hooker admitted, was an important factor in the Union defeat.

Arriving on the field at Gettysburg late on July 1, he was called upon the next day to place batteries and ensure sufficient ammunition in all three sectors of the defenses manned by the Army of the Potomac. His acumen helped stem the looming disaster at the Peach Orchard and Wheatfield on the Union left. It was on the third day, though, that he reached the pinnacle of his career.143

Hunt first had to ensure proper support for the Federal right flank at Culp’s Hill during the morning. Army commander Meade looked for Lee to attack in the center, along Cemetery Ridge, and Hunt next busied himself in readying the Union artillery for an infantry assault. While the Army of Northern Virginia unleashed its entire artillery to soften up the Federal position for the charge, Hunt kept admonishing his gunners to save and target their return fire. Such carefulness resulted in a dispute with infantry general Winfield Hancock, who wanted the return fire of cannons to embolden his soldiers as they awaited Lee’s assault. Hunt disagreed; the guns were best employed in hitting real artillery targets and defending against massed infantry, not merely as morale boosters.

This hard-won wisdom paid off for the Union side once the Confederate batteries grew silent and long lines of infantry emerged from behind their positions. Stepping off for the mile-long hike across open fields to the Federal lines, the thousands of Rebels were an imposing sight—except to Henry Hunt. His artillerymen let loose with a storm of shot and shell that staggered the gray divisions and pushed them toward the left, squeezing the attack into a narrow section of the Union lines near a stone wall and copse of trees. To here, in the epicenter of danger, Hunt spurred his horse. He was the only mounted officer on Cemetery Ridge, conspicuous by his height, uniform and by firing a sidearm at the enemy.

Bruce Catton painted the scene in Glory Road when soldiers

heard the uproar of battle different from any they had ever heard before—“strange and terrible, a sound that came from thousands of human throats, yet was not a commingling of shouts and yells but rather like a vast mournful roar.” There was no cheering, but thousands of men were growling and cursing without realizing it as they fought to the utmost limit of primal savagery…Gibbon was down with a bullet through his shoulder, Webb had been wounded, and Hancock was knocked off his horse by a bullet…Except for one valiant staff officer, there was not a mounted man to be seen. Hunt was in the middle of the infantry, firing his revolver.144

General Alexander Webb, commander of the center of the Union line, would much later recount the scene to an illustrator:

I was dismounted. In fact, we were all dismounted…Could you typify the artillery, which were firing grapeshot over our heads into those fellows, by representing Hunt, the Chief of Artillery, on horseback, just looking over the rear of my lines. That’s good!…Another thing I remember, I looked around and there I saw Hunt who had ridden up, and was popping at them with a revolver. I had to laugh; he looked so funny, up there on his horse, popping at them…He was right at the line, my men, you could put him here; that would introduce it…That’s it. That is true. That is on oath, and the first time I have seen it correct…Kelly: Here is Hunt. Webb: Yes, make him coming up with some men. Kelly: Why did you laugh, when you said he used his pistol? Webb: Because he looked so funny picking at them; I did not need his little pistol.145

Hunt’s horse was shot and went down, momentarily trapping the general’s leg. Several of his gunners helped him up as Union infantry came running to push back the Southerners. In a moment, it was over. The Army of the Potomac, infantry and artillery together, had been too much for Pickett’s charge. Henry Hunt had been instrumental in turning back the high tide of the Confederacy.146 He went on to serve, but it would be hard to reach this pinnacle again.147

General Israel B. Richardson.

Not every general was so fortunate. At Antietam, Israel Richardson went down from an artillery shell wound while leading his division at Bloody Lane. Richardson was a five-year cadet at West Point, graduating toward the bottom (thirty-eighth in a class of fifty-two). His academic performance was eclipsed during the Mexican War, when he twice was brevetted for bravery. Resigning from the army in 1855, he moved to Pontiac, Michigan, to begin civilian life as a farmer.

The outbreak of war brought him back as captain of the Second Infantry. He commanded a brigade at First Bull Run and was promoted first to brigadier then major general. He fought during the Peninsula Campaign and at South Mountain. On September 17, 1862, he led his troops into the single bloodiest day of the war. After being wounded, he was taken to the Pry House, headquarters of army commander McClellan, behind the lines.148 He had the honor of a visit from the president, and his wife came to his side to help his recuperation. Although not immediately life-threatening, Richardson’s wound became infected, and he came down with pneumonia. On November 3, 1862, he died.

The site of his wounding is marked today on the Antietam battlefield just below the observation tower at the Sunken Road. Vehicles travel down Richardson Avenue to gain access to one of the most historic portions of any Civil War site. The marker, central on the battleground, is testimony to valor on that awful day:

I looked over my right shoulder and saw that gallant old fellow advancing on the right of our line, almost alone, afoot with his bare sword in his hand, and his face was as black as a thunder cloud; and well it might be, for some of our own men, turning their heads toward him, cried out, “Behind the haystack!” and he roared out, “God d—— the field officers!” I shall never cease to admire that magnificent fighting general who advanced with his front line, with his sword bare and ready for use, and his swarthy face, burning eye, and square jaw, though long since lifeless dust, are dear to me.149

Like Richardson, Alpheus Williams had embraced Michigan later in life. Moving to Detroit in 1836 at the age of twenty-six, he made it his lifelong home—with one major interlude: military service for his state that began (unofficially) in 1860 before the war erupted and lasted until its end. He had no West Point background to commend himself to the Union effort, only service as a militia officer whose troops never got into action during the Mexican War. Commissioned a brigadier general in August 1861, he commanded troops in both theaters and assumed temporary command of the Twelfth Corps at Gettysburg on the right flank at Culp’s Hill. “Pap” Williams, as his troops affectionately called him, never rose beyond brigade rank, yet he was one of the most reliable officers of the War. Sherman wrote of him: “He is an honest, true, and brave soldier and gentleman. One who never faltered or hesitated in our long and perilous campaign. He deserves any favor that can be bestowed.”150

General Alpheus S. Williams.

None was by the War Department even though “Brigadier General Alpheus Williams led a division longer than any other in the Army of the Potomac.”151 The people of Detroit compensated for the lack of national recognition by erecting a magnificent equestrian statue of him and one of his horses—they were named Yorkshire, Major and Plug Ugly—on Belle Isle.

Just as overlooked, locked in an attic trunk and virtually untouched since the author’s death, the papers of one of Michigan’s generals were revealed in 1999. Orlando Willcox was a Detroit native. He graduated eighth of thirty-eight in the West Point class of 1847, ahead of A.P. Hill, Ambrose Burnside, John Gibbon, Charles Griffin and Henry Heth. A veteran of Mexican and other conflicts, he was an obvious choice to head up the three-months’ regiment that answered the call for volunteers after Fort Sumter. Wounded and captured at First Bull Run, he was exchanged and returned to a hero’s welcome in Detroit in August 1862 after thirteen months’ imprisonment.

His remarks to the crowd are insightful, preceding issuance of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation in September:

Here is a monster that lies curled up in our midst, and that threatens, with its scaly coils, to crush out freedom, and its name is slavery…There is no more need of talking about measures to put out slavery, or measures to protect the domestic institutions of the South; for this war, with its thunder and its mighty revolutions, is of itself crushing out slavery, and you need not say anything more about it.152

General Orlando B. Willcox.

In the thick of fighting, Willcox lost two horses to enemy fire at Antietam but was poised to strike a crippling blow against Lee’s weak right when ordered (three times) to withdraw. He was acting corps commander at Fredericksburg and directed troops on the assault at Marye’s Heights. After transfer to the western theater, he was stationed at Indianapolis in a support role but aided in the capture of John Hunt Morgan during the raid across the Ohio River in 1863. Restored to front-line command in March 1864, Willcox commanded a division during the Overland Campaign and at the Battle of the Crater. On August 19 at the Weldon Railroad outside of Petersburg, “Willcox and his division saved the day.”153 His sector was the target for Lee’s final break-out attempt at Fort Stedman on March 25, 1865, and Willcox’s troops successfully defended their lines. Within a week he led the breakthrough that impelled Lee’s evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond, leading to the surrender at Appomattox on April 9.

The modern-day editor of his papers recaps: “Willcox had little, if any, political influence to exercise during the war, each of his promotions being earned by his seniority and merit alone.”154 From Bull Run as colonel of the First Michigan to the Civil War’s end, from prison confinement to receiving the Medal of Honor, Willcox was the epitome of the nonpolitical general. His comparative lack of notoriety perfectly represents how history did not accord Civil War Michiganders their full due.

Other general officers with Michigan connections served without much fame but just as faithfully.155 In the West Point class of 1846 graduated U.S. Grant, twenty-first out of thirty-nine. Five positions ahead of him was Christopher Columbus Augur, who had moved to Michigan when a boy. He served in the Mexican War and out West against the Plains Indians. The commencement of the Civil War found him commandant of cadets at West Point. In November 1861, he was promoted to brigadier general and commanded troops during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign. At the August 9, 1862 Battle of Cedar Mountain, he was severely wounded and subsequently received promotion to major general. He transferred to the western theater and served in the capture of Port Hudson, Mississippi, in July 1863. Brought back to head the Department of Washington, he escorted President Lincoln’s body from the Petersen House to the White House after the assassination. It was an honor to a general who himself bore the scars of war.

Russell A. Alger, orphaned at the age of twelve, moved to Grand Rapids before the war to work in the lumber industry. Commissioned a second lieutenant in the Second Cavalry, he was involved in over sixty battles, wounded four times and led the first Union troops into Gettysburg on June 28, 1863. He was again wounded in the pursuit of Lee’s army after the battle. At Trevilian Station in June 1864, his command “gallantly charged down the Gordonville Road, capturing 1,500 horses and 800 prisoners” according to Sheridan’s report. At war’s end, he received brevets as brigadier and major general. Resuming civilian pursuits, he moved to Detroit, where he became a leading citizen. He was elected governor of Michigan in 1884, was secretary of war in the McKinley cabinet from 1897 to 1899, was appointed and subsequently elected to the United States senate and died in Washington, D.C., in January 1907.

Israel C. Smith was born in Grand Rapids in March 1839. Enlisting as a private, he was promoted to lieutenant and captain, noted for bravery at the Battle of Fair Oaks in June 1862, wounded twice at Second Bull Run and once at Gettysburg and, on several occasions, exhibited great personal courage in the face of the enemy. He was transferred to the west in 1864 after recovering from his last wounding. Brevetted a brigadier general in March 1865, his postwar career was equally distinguished.

Henry Baxter was commissioned captain of Company C, Seventh Infantry, at age thirty-nine, on August 19, 1861. He was wounded in action at Antietam, led troops at Fredericksburg and received brevets as both brigadier and major general for gallant and meritorious conduct at the Wilderness in May 1864, Dabney’s Mill in February 1865 and Five Forks in April 1865. He was honorably discharged on August 24, 1865, having served for four years and two days.156

And then there was Custer. Much has been written of his meteoric career—by one count, some sixteen hundred books. Among all of the general officers connected to Michigan, Custer garnered the greatest public exposure. He “was, in judgments handed down then and now, the ideal cavalry general,” whose “leadership during the Civil War was nothing short of outstanding.” His monument looms in downtown Monroe, signifying iconic status as the Michigan officer whose name would not have risen so high absent a post–Civil War end.157