Orlando Willcox received his commission as colonel of the First Michigan Infantry, a three-months’ regiment, on May 1, 1861. Before those three months were up, he was a prisoner of war and would be for many more. Though early in the conflict and far harsher conditions awaited captured soldiers later on, Willcox’s experience is chilling. Commencing with the first significant battle of contending armies, North and South, Americans became POWs at the mercy of fellow Americans.

Treated well by his military captors and attentive medical staff near the Manassas battlefield, the recovering Willcox was soon transported by train along with other captives to Castle Pinckney in Charleston Harbor. The trip was an ordeal, “the worst by far I ever took.”190 Several times forced to stay in the cars for hours, with little food (mostly poor) and no water, the prisoners were “such a haggard set of wretches I never beheld.”191 After detraining at the Charleston station, they were marched not to a military facility but the town jail. Such treatment equated their status with common criminals—as the Confederacy soon classified them. They were held as “pirates and common felons” in retaliation for treatment of Rebel privateers up North.

While awaiting execution, Willcox found himself in solitary confinement on rations of bread and water. When the U.S. government relented on the privateers, his condition improved. He was moved inland to Columbia and confined to the city jail. Before long, prisoner exchanges commenced, and fellow officer William Withington—a “gallant Christian soldier and gentleman” who had rescued the wounded Willcox—was released.192 As events progressed, Willcox and a contingent of forty Michigan soldiers were taken back to Richmond to await exchange. Initially held in a hospital, after several days they were confined to Libby Prison, where conditions were the worst he had endured.

Writing after the war, Willcox placed his time shuttling between prisons in perspective. The old tobacco warehouse was not Andersonville—site of thousands of deaths amid starvation—and he judged that Confederate POWs endured harsher treatment in Northern prisons. Still, ubiquitous filth and vermin made imprisonment a squalid experience. And another transfer, not northward to freedom but southward to Salisbury, North Carolina, inflicted emotional distress that exceeded any improvement in living conditions. Once more, his party was threatened with reprisal if prisoners at the North received a capital penalty. In August 1862, finally, Willcox was exchanged and transported into Union hands at Fortress Monroe.193 He returned home to a hero’s welcome.

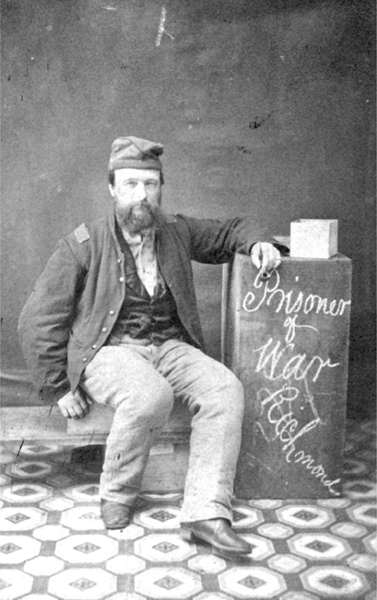

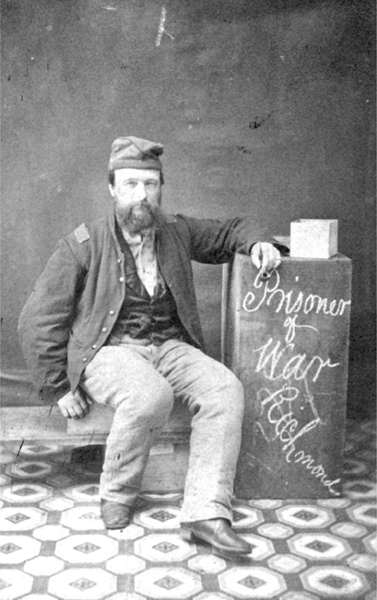

An unidentified Eighth Infantry soldier is pictured next to a sign that says, “Prisoner of War, Richmond.”

Libby Prison was where Lieutenant James Wells, officer in the Eighth Michigan Cavalry, ended up after capture near Chattanooga in September 1863. He was marched to Dalton, Georgia, shipped in crowded freight cars to Atlanta, and then reshipped to Richmond. At Libby Prison, he waited vainly for exchange. After six months, he joined an effort to escape—a wildly successful one, for over one hundred soldiers fled to freedom. After a first attempt through a sewer failed, a cadre of prisoners worked for more than seven weeks on a tunnel from the east end of the prison basement, under a street, to the other side and a hidden exit. The prisoners went through the tunnel on the night of February 9, 1864, Wells among them. He and forty-two others successfully made the Federal lines. Going without food, crossing rivers and moving largely at night, he linked up with two other escapees and, out of resources, finally hailed approaching cavalry even though it meant taking their chances. The horse soldiers were Union, on patrol to seek out the escaped prisoners. Among those brought in was William B. McCreery of Flint, a colonel in the Twenty-first Michigan Infantry, wounded six times during the war.194 Regained freedom for such men was very sweet.195

Wells hailed from Schoolcraft and had enlisted as a sergeant in December 1862. He was promoted to second lieutenant in March 1863; six months later, he was a prisoner. After his escape, he was promoted to captain in May 1864 and captured again during Stoneman’s Raid in August 1864. This time, he was exchanged only a month later. His first encounter with prison life was trying: he was constantly hungry and suffered, along with many cellmates, from a feeling of unrest “which, if yielded to, often led to despondency and even insanity.”196

Such experiences were not limited to a few Michiganders, and some had similar endings. Clement A. Lounsberry enlisted at Marshall in Company I, First Infantry, on April 22, 1861, for three months; he was eighteen. Like Willcox, he was wounded and taken prisoner at the Battle of First Bull Run. A year later, he was exchanged, whereupon he enlisted for a three-year term in Company I, Twentieth Infantry, as first sergeant. Promoted to second lieutenant, he was again wounded and taken prisoner during the aftermath of the Battle of Chancellorsville in May 1863. Lounsberry returned to the regiment and was wounded in action yet again at the Battle of Spotsylvania in May 1864. He became a brigade aide de camp and assistant adjutant general, finally receiving promotion to colonel. Thrice wounded, twice a prisoner, Lounsberry received promotion and commendation for gallant and meritorious services during the Overland Campaign.

Clement A. Lounsberry—thrice wounded, twice prisoner—enlisted at age eighteen on April 22, 1861. He rose to brevet major for gallant and meritorious services during the Overland Campaign.

One of the most famous of POWs was Hazen Pingree. Born August 30, 1840, in Maine, he volunteered in a Massachusetts regiment and was captured at the South Anna River in 1864. Initially imprisoned in Virginia and North Carolina, he was transported to Andersonville prison near Americus, Georgia. When Sherman’s march to the sea threatened the camp, Confederate authorities transferred him to Millen, Georgia. During a roll call for an exchange in November 1864, he assumed the identity of the other prisoner and escaped. Returning to the blue lines, he was present at Appomattox and had the pleasure of witnessing Lee’s surrender up close and personal. After the war he moved to Detroit, began working in a shoe factory and started up a firm that grew into one of the best-known footwear manufacturers in the nation, Pingree & Smith. In 1889, he ran successfully for mayor of Detroit. In 1897, he was elected governor; forced to decide between retaining the mayoralty and governing the entire state, Pingree chose the Lansing post, where he served two terms.

Commissioned officers and enlisted men did not typically find themselves together. Lieutenant Colonel Frederick Swift of Detroit was captured at the Battle of the Wilderness. While being escorted to the rear and transported to a camp, he witnessed a Rebel general officer managing the battle. His captors confirmed: it was Robert E. Lee. En route to Georgia, he and a handful of others jumped off the moving train and hid out for several days, aided by a slave who provided food and guidance for their escape. Alas, they were recaptured and taken to a prison at Macon, where conditions were not as bad as Andersonville only because of the smaller number and rank of the inmates. Provisions were “very scant, poor corn-bread and worse bacon,” yet the officers felt fortunate when learning of the privation at the other Georgia camp. To keep up their spirits, some men played whist, euchre, chess and checkers. Others died of despair and homesickness. Swift did not wait long for an exchange; taken to Charleston and locked up in the town jail for a time, he and companions later were placed under house arrest. Finally, the day of the ceremony arrived. The Union officers boarded a Confederate ferry, which steamed out toward Fort Sumter. Once safely transferred to a larger U.S. frigate, the prisoners rejoiced and were brought to tears when the blockading squadron outside the harbor lined up and fired salutes as their ship of freedom steamed past in review.197

Not all POW stories ended so joyfully. More than seven hundred Michigan soldiers and sailors never escaped, never were exchanged or never walked out of Andersonville alive.198 From Fifth Cavalry soldier C.M. Abbott to John Zett of the Twenty-second Infantry, with artillerymen and engineers and sharpshooters included, the names of those who died there fill a dozen pages. The roster understates the effects of confinement, for others made it all the way back to Michigan only to succumb, literally in the arms of their loved ones.

Some four decades after the war, the governor—an escapee from Andersonville—and a delegation of legislators and dignitaries dedicated a monument there, on Memorial Day, to those who endured and those whose final glimpse was of the walls of the prison stockade. The remains of two men were found while excavating the foundation for the memorial within those walls. Unlike several other states, the Michigan monument was situated not in the cemetery but on the ground where the prisoners lived and died. The governor recalled “the dense masses of the prisoners,” remembered pitiless skies and suffering that day by day struck down the weakened “right and left.” His remarks served as an epitaph for the sacrifice that all Michigan prisoners in all camps had made: monument there, on Memorial Day, to those who endured and those whose final glimpse was of the walls of the prison stockade. The remains of two men were found while excavating the foundation for the memorial within those walls. Unlike several other states, the Michigan monument was situated not in the cemetery but on the ground where the prisoners lived and died. The governor recalled “the dense masses of the prisoners,” remembered pitiless skies and suffering that day by day struck down the weakened “right and left.” His remarks served as an epitaph for the sacrifice that all Michigan prisoners in all camps had made:

A bone ring carved by Thaddeus L. Waters, Second Cavalry, while imprisoned in Andersonville.

This is sacred ground, consecrated by the suffering of men who here gave “the last full measure of devotion.”

Theirs was not the glory of death on the firing line; the reaper touched them not amid the roar and the shock of battle. Penned in by the dead line, wasted by disease, far from home and loved ones, they were mercifully mustered out, leaving as a heritage to the nation the memory of a devotion as limitless as eternity itself.199