The Union victory at Chattanooga propelled Ulysses S. Grant into the position of general in chief and command out East. He would face a new kind of adversary in Robert E. Lee, the Rebels’ main hope for independence on the battlefield. The Confederacy was not limited to that route though, for November would bring an opportunity for voters in the North to determine whether Abraham Lincoln, or another candidate, would man the nation’s helm in 1865. Peace was still a possibility and, with it, independence.

Something had changed, though, during these several years in the attitudes of individual Michigan soldiers. They were fighting for the Union, and they fought against the “slave power.” What about freedom for African Americans? Perhaps, but in the spring of 1864, the Eighth Infantry demonstrated they were, indeed, fighting for a new birth of freedom. A Rebel slave owner appeared at their picket line outside of Annapolis, seeking to reclaim his runaway. The men of the Eighth “pounced” on the Southerner, who narrowly escaped with his life. He was no owner of property—he was the reason they were so far from home, seeing friends and neighbors wounded and killed. The Emancipation Proclamation, far from a divisive act splitting Northern brothers apart, had taken hold of their head and heart.200

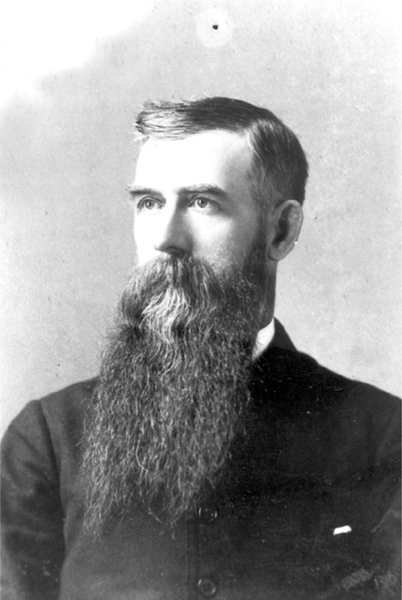

An important factor in the esprit of Michigan units was a War Department policy that allowed special designations for those who had fought and would fight again. Charles B. Haydon of Kalamazoo, a practicing lawyer when the war began, had enlisted in the Second Michigan Infantry in April 1861. He fought at First and Second Bull Run, in the Peninsula campaign and at Fredericksburg. His unit was transferred to the West, where he suffered a grave wound at Jackson during the Vicksburg campaign. Fortunately, he recovered. Promoted to lieutenant colonel, Haydon became responsible for campaigning among his men to gain the designation of “veteran volunteers,” a proud title signifying that they were not draftees and had reenlisted for the war’s duration. It would only be awarded if a sufficient number of the men reenlisted, and they would be rewarded with a thirty day furlough. Haydon “campaigned strenuously for re-enlistment” and succeeded. Nearly two hundred re-signed.

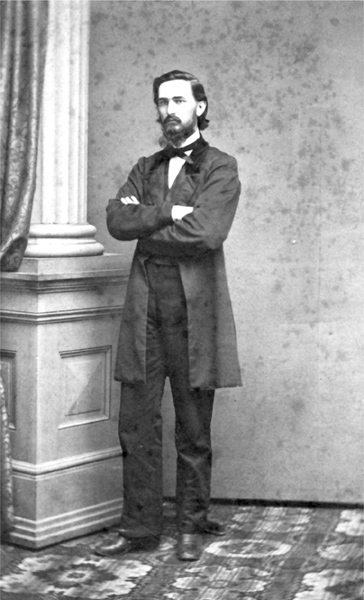

James M. Greenfield, Seventh Infantry (Ontonagon County), enlisted at age twenty and reenlisted in December 1863. He was wounded in action at Meadow Run, May 31, 1864, and discharged for disability.

In a diary he kept diligently during his service, Haydon bragged on his men. On the way home to Michigan to enjoy the furlough with them, he recorded this February 17 entry: “I have taken a very severe cold & am almost sick.” It was followed on February 20 with an item about attending a theater play: “Everybody had a bad cold & coughed.” There are no entries after February 21. On March 14, 1864, veteran volunteer officer Charles B. Haydon died of pneumonia in a Cincinnati military hospital. He had not lived to see his thirtieth birthday.201

After their respite, the Second was ordered back to the East. On May 6, it crossed the Rapidan River in Virginia and marched into “the Wilderness” with the rest of the Army of the Potomac. So named because of its dense tree cover, the thickets hid approaching Confederates who smashed into the Union right flank, commencing a running battle that would not cease for two weeks. Enduring thirty-eight casualties in the first two days, the regiment was ordered to march to the nearby courthouse town of Spotsylvania, where it went into action again on May 10, 11 and 12. At one point, the Confederates shot down every artilleryman in a New York battery and threatened to capture their four guns. The Second’s commanding officer “immediately called for volunteers…who manned the guns, putting in a double charge of canister to that already in, and with these guns, loaded to the muzzle, opened a terrific and destructive fire” on the enemy.202 The artillery was saved, as was the nearby Union line. It was the latest in a string of heroic exploits by the unit.

The famed Iron Brigade took part in the Battle of the Wilderness. Emile Mettetal did also. He had enlisted in the Twenty-fourth Michigan Infantry on August 12, 1862, at the tender age of nineteen. According to the company descriptive book, he was born in Redford, stood five feet, eight inches, had descended from French Canadians and was a farmer. A member of Company I, he had fought at Fredericksburg and other battles. After the Wilderness, he was declared missing. His name appeared on a different roll: the list of prisoners in the Andersonville camp near Americus, Georgia. He would be transferred to Camp Florence in South Carolina when Union troops approached. Early the next year, he would be paroled for reasons of illness and sent to Wilmington, North Carolina, for transport back north. He never made it. Although he may have died before leaving Florence203 or Wilmington, Mettetal may have made it onto the steamer General Lyon, the transport for some six hundred prisoners back home. The ship was in a storm off Cape Hatteras and caught fire when the pitching waves tipped over kerosene barrels, causing the ship to sink. Only thirty-four made it to shore. Emile was neither on the passenger list nor among the survivors.

A great sacrifice was paid on May 12 at Spotsylvania by the Seventeenth Michigan. Its division was ordered to charge the enemy lines and take an exposed artillery battery. Advancing “under a tremendous shelling,” it found itself confronting a larger Confederate force that was about to make its own charge:

The lines of the enemy extended in a circle around the left of our regiment, and closed on our rear, opening a heavy fire both in front and rear, at one time having the entire regiment prisoners. The men fought desperately hand to hand with the enemy, and during the struggle 43 men and 4 officers succeeded in making their escape…In this charge the loss of the regiment was 23 killed, 73 wounded, and 93 taken prisoners, out of 225 engaged.204

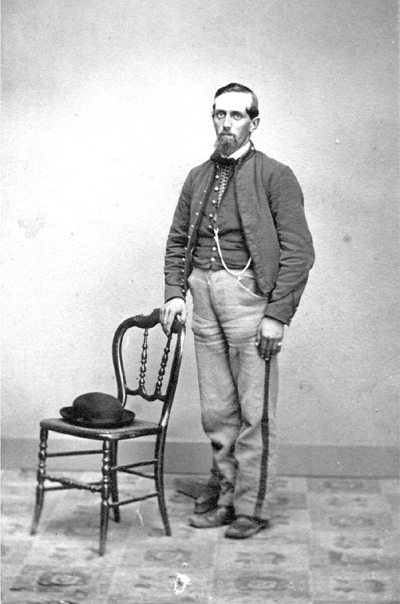

Roswell P. Carpenter, Twentieth Infantry (Ann Arbor), held ranks of first lieutenant, division ordnance officer and captain. He was killed in action on May 12, 1864, at Spotsylvania.

Never did men fight with more valor.

Spotsylvania was truly a bloody affair. One of the notable exploits on the Union side was an attack by Colonel Emory Upton on the “Mule Shoe Salient.” Military experts have ever after lauded the brilliance of the assault. Upton would later write the standard textbook on tactics for the U.S. Army. Several aspects of the Spotsylvania attack were not noted as time went by. First, it was not ultimately successful. Second, it was not originally Upton’s idea. He had received his early training as an artillerist under Henry Hunt—and thus was a disciple of the teaching of concentration of firepower that Hunt had demonstrated on several battlefields.205

Despite fearful losses in these May battles, Grant did not give up. He continued to press Lee, seeking to maneuver him into a battle outside of entrenchments where a decisive victory could be won. Lee countered every move, until a surprising day when the Union forces moved swiftly and appeared outside of Petersburg to the south of the Confederate capital, threatening to cut off supply lines and forcing Richmond’s surrender. The advance, however, was botched, and Lee was able to thwart Grant’s strategy. For a while, that is. For the next few months, the Union lines around Petersburg and Richmond would extend farther until they nearly reached and could cut off the rail lines that supplied Lee’s troops. On August 25, 1864, Michigan soldiers battled at Reams Station, Virginia. Culminating a week of intense fighting outside of Petersburg, eleven different Michigan units were involved in actions that left many casualties, including Major Horatio Belcher of the Eighth Infantry. The Flint officer had gone off to war three years earlier in August 1861; he was killed on August 19.

In a bold move designed to break Lee’s lines, Grant approved a plan for a tunnel underneath the Confederate lines near Petersburg that would be exploded and create a breach in their lines that Union troops could exploit. The tunnel was dug, explosives were placed, a detonator was set off and tons of earth and humanity were flung high in the air in an explosion that shocked even its planners. The Union troops were ordered in, but they became trapped inside the crater, struggling to climb up its unstable sides and facing Confederates who surrounded the men in the hole and poured an intense fire into the hapless blue clads. Not all were overcome: “Among our troops was a company of Indians, belonging to the 1st Michigan S.S. [Sharpshooters]. They did splendid work, crawling to the very top of the bank, and rising up, they would take a quick and fatal aim, then drop quickly down again.”

The Native Americans were not the only Michigan units involved, and they would all encounter a deadly situation together:

The sharpshooters, on the far left of the disorganized Union forces, were joined by the 2nd and 20th Michigan. They had gained a foothold on the Rebel works…Unit cohesion was impossible, and it is doubtful orders could have been heard, much less followed. Men clawed into the sides of the crater in a vain attempt to evade Confederate fire raining down on them. Under a pitiless sun, the corpses soon bloated and became breastworks for those who were still alive.

Through it all, the Indians kept their composure. Lieutenant William H. Randall of Company I, captured during the fight, remembered that “the Indians showed great coolness. They would fire at a Johnny and then drop down. Would then peek over the works and try to see the effect of their shot.” Lieutenant Bowley claimed to have seen that “some of them were mortally wounded, and clustering together, covered their heads with their blouses, chanted a death song, and died—four of them in a group.”206

Their sacrifice proved for naught; the Federals retreated, and Grant settled in for a siege.

In the West, the commander put in charge was William T. Sherman, and he was determined to take Atlanta. Second only to Richmond in military importance, the Georgia city was a railroad hub and armament supplier. Its fall would likely free Sherman’s army to march northward toward Richmond and signify desperate times for the Confederacy. By a series of flanking movements, Sherman’s forces maneuvered the Rebel army back into the outskirts of Atlanta. Several battles were fought en route, and at Peach Tree Creek, on July 12, Captain Frank Baldwin of Constantine, Company D, Nineteenth Michigan Infantry, won his first Medal of Honor by “leading a countercharge…under a galling fire ahead of his own men, and singly entered the enemy’s line, capturing and bringing back 2 commissioned officers, fully armed, besides a guidon of a Georgia regiment.”207 Just nine days later, Battery F of the First Michigan Light Artillery was credited with being the first Union battery to throw shells into the Confederate stronghold.208 Not long after, the city fell, and Union troops marched in. Back in Detroit, “amid great rejoicing an impromptu celebration was arranged. A national salute was fired, brilliant fireworks displayed, and speeches were made” by U.S. senator Jacob Howard and other community leaders.209

Sherman now developed a new plan: he would march to the sea, his target being Savannah, Georgia, making the South “howl.” Leaving no military capabilities behind, Sherman ordered the depots, rolling stock and warehouses of Atlanta set on fire. The Michigan Engineers and Mechanics played a large part in obeying the order. The regiment also had a large role both in the march itself, by actively opening roads and fighting when attacked, and in the opposition to the Rebel army that threatened Sherman’s rear, by maintaining the railroads and aiding the capabilities of the Union contingent left behind to confront that army. A total of some three thousand soldiers would at various times be counted among the regiment. It would end the war with more men than it had at the start.

John Henry Carpenter, Fourteenth Infantry (Washtenaw County), reenlisted on April 13, 1864. He was killed in action on August 7, 1864, near Atlanta.

After the fall of Atlanta, Battery F of the First Light Artillery was sent back to Chattanooga, where it remained until being posted to Nashville. On October 26, 1864, the Twenty-eighth Michigan Infantry left for the front. Organized from communities in the southwestern Lower Peninsula, the regiment left its encampment at Kalamazoo for the Tennessee capital. In mid-December, it saw action at the Battle of Nashville, where the Rebel Army of Tennessee was crippled and put out of commission. Battery F, too, was in the fight.

The November election could have produced a result that, in Lincoln’s judgment, would make winning the war impossible. The Michigan electorate—including its soldiers away at the front—cast their votes and decided on prosecuting the war rather than peace negotiations. The Michigan soldier vote was dramatically in Lincoln’s favor. He won 9,402 to 2,959, a margin of 76 percent. Some were landslides: the Ninth Infantry went for Lincoln 413–95. The fabled and bloodied Twenty-fourth voted for him 177–49. Soldiers convalescing in hospital wards voted overwhelmingly for the Union ticket, 388–46. The war would continue.

It had been quite a year. At the start and for much of its duration, the prospects for the reelection of Lincoln looked grim. Michigan’s political leadership helped clear the way for Lincoln’s renomination, but a war-weary North faced a difficult decision. As late as September, Lincoln expected the worst. Then, Atlanta fell. If Lincoln’s fate had depended on Michigan volunteers, though, he need not have worried. From war’s commencement until the last day of 1863, Michigan had furnished 53,749 troops, enough for an entire army. Though an impressive number, the first ten months of 1864 proved more astounding. A total of 27,616 Michiganders were in uniform for the first time. The analysis: “The striking fact is exhibited by these figures that during ten months only of 1864 the State of Michigan had furnished more than half as many men for the service as were sent from the State during the whole of the first three years of the war, and of this large number of men actually furnished, only 1,600 were drafted.”210

Far from surrendering to war-weariness, Michigan was stepping it up.