They came from every corner of Michigan on the Fourth of July 1866, the ninetieth anniversary of the signature event that launched the American republic. There were no highways, no motor vehicles, only a few rail lines that linked populated areas, so they also came by horse, by buggy, by wagon, by walking. They came, men of different ethnicities, convinced that this muster was every bit as important as any they had attended. These soldiers of democracy came together; some had received a delayed birthright of freedom thanks in no small part to their own military service. They came because of their devotion to the nation, to the state that had fought its way into the Union and for the people who would not allow the permanence of the United States of America to be threatened.

They were “men set apart,”228 these Michigan Civil War veterans. Some bore the scars of battle on their person: a missing hand, arm or leg; exhibiting a limp or shuffle or crutch. Others showed no visible evidence of suffering; still, in a tangible way, their wizened appearance conveyed a near-escape from death. Faded blue uniforms, careworn caps, tarnished brass buttons and well-trod boots proved who they were. Blue, yes, a sea of blue was massing this day, blue of those lake-bound shores, blue of the Michigan summer sky, blue of the field upon which the state coat of arms flew on flags they had followed into harm’s way.

They shared a common bond forged in the storm of shot and shell of over eight hundred conflicts from Ohio to Florida and Pennsylvania to Louisiana. That bond had been strengthened as they bivouacked together, marched together, shared privation and plenty together, endured temporary defeat and celebrated ultimate victory together. Now, with their mission to restore the Union accomplished, they gathered at Campus Martius, the drill ground and rallying point in Detroit for Michigan’s militia since 1788, to perform one last act of service. In that public square, five years earlier, an enthusiastic crowd of citizens—men and women—had presented a set of colors to first responders of the First Michigan Infantry as they departed for war. Today, there was a mission yet to be completed: Michigan would be an early adopter of the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution, seeking to fulfill the new birth of freedom achieved by these soldiers and citizens. But on this July Fourth, a gathering of men and women made equally enthusiastic witnesses to the assembly of the blue-clad who would entrust symbols of the struggle into the state’s care for all of posterity.

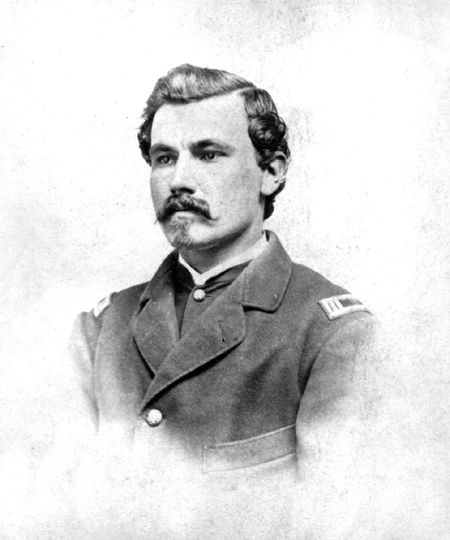

Sergeant William R. Dodsley, Twenty-fourth Infantry (Detroit), Iron Brigade, enlisted at age twenty-two on August 5, 1862. He was mustered out on June 30, 1865.

Attached to war-scarred staffs, regimental banners—altogether, there were 163 of them—were proudly borne into the square. Many were “mere shreds, tattered, torn and bullet-pierced,” “illustrative of valor,” “mementoes of patriotism.”229 There was that flag of the First Infantry, a unit in both battles of Bull Run. There was the scrap of the Twenty-fourth Infantry, illustrious component of the immortal Iron Brigade. There was the flag of the Eleventh Infantry that charged up Missionary Ridge into the teeth of Confederate fire. There was the guidon of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade, mounted troops who had evened the score with vaunted horse soldiers of the South. There was the flag of the Seventh Infantry that made an amphibious assault across the Rappahannock under fire of the Army of Northern Virginia at Fredericksburg. There was the banner of the First Engineers who had built the “Michigan Bridge” to open the key supply line to Chattanooga. There was the flag of the Seventeenth Infantry, the “Stonewall Regiment,” who had charged up and over the wall near Antietam. There were banners representative of all forty-six regiments and several other independent companies, some proudly waving, others so fragmentary that were gingerly carried by hand.

For those flags that still could fly, their custodians felt the full honor of today’s duty. All too many color bearers had carried these flags into the fight never to return; their graves, along with those of thousands who had followed them into battle or who had never emerged from behind prison walls, served as silent testimony to the gravity of this ceremony. As was now second nature, the Michigan men marched this day in rows and columns, orderly and straight, just as they had during the two days in May 1865 when passing in the victorious grand review of the Union armies in the nation’s capital. They stood this day in those rows and those columns, orderly and straight, symbolic of the fallen comrades who now lay in rows and files, orderly and straight, in cemeteries at Gettysburg and Nashville and so many other hallowed places throughout America.

One of their own generals, overlooked for promotion despite his stalwart leadership, despite having served from First Bull Run to the final siege of Richmond, spoke for those veterans present and those unavoidably absent. Orlando Willcox reminded all of why these men had gone into combat: “not to establish or defend a throne, neither for spoils, oppression, nor any other unworthy object, but simply for the Union, and as soon as may be let the ancient foundations of the Constitution be restored with only the crumbling stone of slavery left out, and with liberty guaranteed to all.” His voice rang out for the missing fourteen thousand, those who “return not to receive your thanks and the plaudits of their grateful countrymen. They walk the earth no more in the flesh, but their fame survives, and their glorified forms bend above us, now, and with hands unseen deck these colors with invisible garlands.”

General Willcox concluded with timeless sentiments: “It only now remains for me, in the name of the Michigan soldiers, to surrender to the State these Flags, tattered but not stained, emblems of a war that is past. We shall ever retain our pride in their glorious associations, as well as our love for the old Peninsular State.”

Governor Henry Crapo replied on behalf of the people of the two peninsulas: “I may venture to give you the assurance that you have the unbounded gratitude and love of your fellow-citizens; and that between you and them the glory of these defaced old Flags will ever be a subject of inspiration—a common bond of affection.”

Battle flag of the Twenty-fourth Infantry.

Crapo spoke of the nobility of these “defaced” banners:

To you they represent a nationality which you have periled your lives to maintain; and are emblematic of a liberty which your strong arms and stout hearts have helped to win. To us they are our fathers’ Flags—the ensigns of all the worthy dead—your comrades, our relatives and friends—who for their preservation have given their blood to enrich the battle-fields, and their agonies to hallow the prison-pens of a demoniac enemy. They are your Flags and ours. How rich the Treasure! They will not be forgotten and their history left unwritten.

Concluding, the governor paid tribute to the raw heroism of farm boys and city clerks by making a solemn vow: “Let us, then, tenderly deposit them, as sacred relics, in the archives of our State, there to stand forever, her proudest possession—a revered incentive to liberty and patriotism, and a constant rebuke and terror to oppression and treason.”

Within a few years, an imposing soldiers and sailors monument, designed by Ann Arbor native Randolph Rogers, would be erected in this square with monies collected from all over Michigan and aided significantly by efforts of its female leadership.230 Four plaques containing bas-reliefs of Union leaders Lincoln, Grant, Sherman and Farragut—famed admiral of Hispanic descent—were featured. Four wingspread eagles stand guard below four women who symbolize victory, history, emancipation and Union. Crowning the fifty-six-foot-high memorial is an eleven-foot-tall female figure, armed with sword and shield, representing Michigan. Ever after at Campus Martius would stand this monument, “Erected by the People of Michigan in honor of the Martyrs who fell and the heroes who fought in defense of Union and Liberty.”

Year after year, veterans of the war for the Union went to their final bivouac.231 Some were buried in Detroit’s Elmwood Cemetery, where the location of their graves fulfilled the promise of America. For here, next to one another, one finds veterans of all backgrounds, blacks next to whites next to Native Americans in a quiet pastoral setting that belies the titanic struggle they fought and won.

It was said so well on that Fourth of July: “while we have souls to remember, let their memories be cherished.”232 Indeed, their memory remains, yet today, our sacred trust.