CHAPTER 2

Dealing a New Hand and Upping the Ante

Following the intensive and violent events on the St. Lawrence and Niagara frontiers at the end of 1813, the first months of 1814 were, by comparison, a period of little active campaigning. However, behind the scenes there was a massive amount of simultaneous planning and strategizing taking place by the principal players on both sides of the frontier. In addition, as the weeks passed there developed an increasing parallel tempo of construction of new military fortifications, supply warehouses, and barracks to prepare for the approaching campaigns on land, as well as the construction of two enlarged naval fleets to contest the control of Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. Both sides made substantial increases to the volumes of military and ancillary supplies that were ordered, produced, transported, and stockpiled during this period. Gone were the days of minor probes, amateurish raids, and ill-supplied expeditions. Instead, an entirely new scale of warfare was to be undertaken, as both sides were determined to make the 1814 campaign the decisive blow that would cripple or entirely defeat their enemy — once and for all.

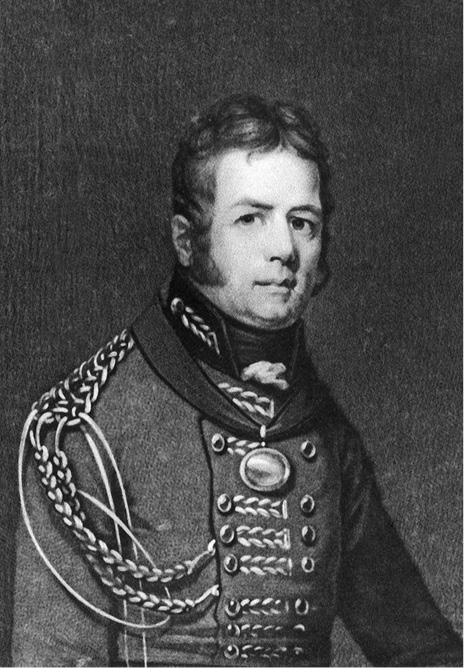

S.W. Reynolds, artist, date unknown, Library and Archives Canada, C-19123.

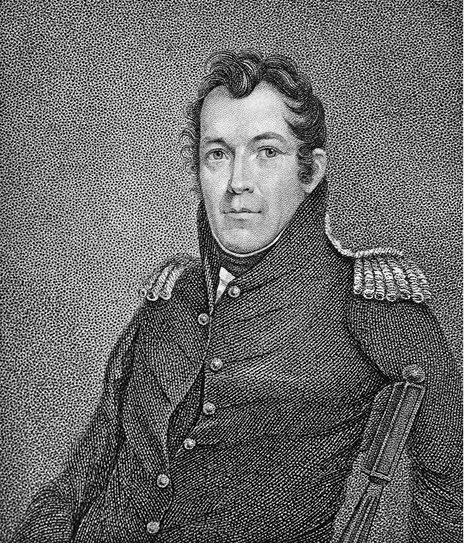

For Lieutenant General Gordon Drummond, the senior British military commander in Upper Canada and lieutenant governor/president of the province’s civilian administration, the neutralization of the American military threats on the Niagara and St. Lawrence frontiers at the end of 1813 enabled him to plan for an offensive campaign in 1814. To this end, Drummond followed the same line as his military/civilian administrative predecessors, by making strong representations to his senior military commander (who was also the governor general of the Canadian colonies), Sir George Prevost, to send additional troops and resources into Upper Canada, where all of the significant fighting over the previous year and a half had taken place. Drummond reasoned that these additional resources were essential if he was to expel the occupying American land forces from the western portions of the province and re-establish his line of communication with the isolated British garrison at Fort Michilimackinac (Fort Mackinac) in the far north. This was to be followed by a period of reconstruction and strengthening of both the existing military depots above Kingston, as well as constructing new shipbuilding centres on Lake Erie for the production of a new British flotilla that would regain the essential transport lines and naval supremacy on that lake. For this latter project Drummond knew he already had the backing of Sir James Yeo, the senior naval commander on Lake Ontario, as Yeo had already proposed a similar project to Prevost the previous December.

To secure his southern flank and prevent any American interference in this plan, Drummond also proposed establishing a strong mobile infantry force at Long Point to guard against any American landing aimed at destroying the planned shipyards, or cutting off his troops on the Niagara frontier, as well as protecting the vital food supplies provided by that area. Finally, he proposed making a daring three-pronged offensive. First, Yeo would lead a force of around two hundred sailors and troops in a march across the frozen Lake Erie to destroy or capture that part of the American fleet that was wintering at Put-in-Bay. At the same time, he (Drummond) would command two columns of troops (cumulatively made up of a total of 750 regulars, 250 militia, 100 Royal Marines, 40 Royal Marine artillery with three field pieces, 400 Native allies, and 20 provincial cavalry) to recapture Amherstburg and seize any American boats wintering there.[1]

In response, Sir George Prevost, while giving an initial qualified approval for this combined offensive operation, continued to expound his own absolute conviction that the American troops wintering along the Lake Champlain and St. Lawrence corridors represented a significant military threat to Lower Canada that negated any argument to send troops into Upper Canada:

… nor indeed is it much my wish to draw the attention of serious exertions of the enemy against that quarter [the Detroit corridor] where we have experienced so much difficulty in forwarding the necessary supplies and from total want of accommodation for carrying on the service … besides other considerations of a still more important nature, induce me to encourage the enemy in selecting a less distant scene of action for the ensuing campaigns But under every circumstance, the unequivocal demonstration … of directing their whole disposable force with their utmost energy against Lower Canada must be as unequivocally done away before I can feel myself qualified in making any alteration in the disposition of the troops below Kingston…. The defence of Lower Canada [is] … a consideration which must never be lost sight of and to which every other, as of minor importance, must give way…. The suggestion of moving a Corps for the recovering our lost position at Detroit is … beyond our means…. One great objection to detaching Corps [from Quebec] to the distant points of the Upper province is that we thereby expose them to a most arduous and critical struggle without the means of supporting or withdrawing them, while we leave ourselves, by such measures, weak and without a disposable force.[2]

— Prevost to Drummond,

January, 5, 1814

However, Prevost’s lack of support became moot when the weather chose not to co-operate with Drummond’s plans, as a fluctuating period of unseasonably warm and cold conditions rendered the Lake Erie ice too thin for an infantry attack to be made, but thick enough to prevent any boats being sailed across without the grave danger of striking ice floes and sinking. Consequently, by the end of February, Drummond was forced to call off the entire expedition. Which perhaps was just as well, for there were plenty of additional matters that required his attention, the most immediate being the lack of provisions and supplies with which to feed his army and all of the refugee Native allies he was responsible for. Consequently, Drummond took the extraordinary step of making an extensive personal tour of inspection of the Grand and Upper Thames river valleys during the first weeks of March to assess the potential resources of food and provisions that could be expected to flow from that area. Upon his return, a far more sombre commander penned his findings to Prevost:

I availed myself of an opportunity to visit that part of the district which lies to the westward, as far as the Delaware town on the River Thames and Long Point and vicinity on Lake Erie. I was much concerned to find that part of the country bordering on the River Thames extremely drained of resources, so much so in fact, as to make it almost amounting to an impossibility to support an adequate force for its protection without drawing all supplies for that purpose from the neighbourhood of Long Point.[3]

— Drummond to Prevost,

March 5, 1814

Shortly thereafter, the situation for the provision of grain for the making of bread was deemed so serious that despite the inevitable negative backlash of public opinion, Drummond was forced to issue the following edict:

York, March 14, 1814 …

Know ye that finding it at present expedient and necessary … I hearby … prohibit the distillation of spirits, strong waters or low wines from any wheat, corn, or other grain, meal or flour within this Province … to the first day of July now next ensuing, under the penalties and forfeitures by the said act imposed.[4]

At another level, due to a deficiency in hard cash within Upper Canada, the main medium of currency had devolved upon army-issued bills of exchange or “scrip,” which was not meant for widespread circulation within the civilian economy. As a result, commodity prices soared as people began to hoard their gold and silver coinage, whilst simultaneously refusing to be paid in the scrip, thus substantially reducing products and produce being offered for sale to the commissariat and quartermaster departments. This issue also had unexpected fallout on the reconstruction work required to prepare the Niagara frontier fortifications of Fort Erie, Fort Chippawa, Queenston, Fort Mississauga, and Fort Niagara for active service, once the campaigning recommenced in the spring.

The first three were essentially fire-gutted and partially demolished shells, capable of no defensive stand if attacked, while Fort Mississauga was only just in the process of being built. Fort Niagara’s buildings were essentially intact, but its external earthworks and picketing defences were in a bad state, as a series of land-slips had caused entire sections to cant over or collapse. While the various garrison troops could be ordered to do some of the manual work on these locations, qualified military engineers and skilled tradesmen were in short supply to do the professional jobs. Hiring civilian contractors and workmen was essential if these fortifications were to be repaired. Unfortunately, as these civilian individuals were already in high demand for other civilian work and military projects (such as those under Yeo at Kingston), few were available for work on the Niagara, and those who were available did not like being paid in scrip. The situation became so bad that, as there were not enough trade workers available to produce new picketing to restore the Fort Niagara defences, Lieutenant General Drummond was forced to authorize the dismantling of the picketing already installed at Fort George and its transportation and re-erection at Fort Niagara! Nor could he accede to the recommendation of the region’s commander of the “Right Division,” Major General Riall, for either the substantial reduction in the scale and dimensions of Fort Niagara defence perimeter (so as to reduce the structural maintenance required and the garrison of troops needed to defend it) or its entire demolition, as Drummond believed that:

… although a considerable proportion of the Right Division will necessarily be employed for its defence, yet a still much greater force of the enemy must unavoidably be engaged in its investment, which force might otherwise be at liberty to act against us in perhaps a far more vulnerable point.[5]

— Drummond to Prevost,

March 22, 1814

In yet another matter, denied the service of additional regular troops from Lower Canada, Lieutenant General Drummond was forced to look to the Upper Canada militias for his new supply of manpower. He therefore revised the regulations upon which his only full-time militia regiment, the Incorporated Militia of Upper Canada, was operating.

Having been formed the previous March, the original intention had been to establish three full battalions of this corps. Unfortunately, insufficient volunteers had stepped forward for full-time service to fill the three-battalion quota. Instead, four divisions of companies of Incorporated Militia had been raised, these being at Prescott (six companies), Kingston (three companies), York (one company), and on the Niagara (three companies). Each of these divisions had already seen significant active service during 1813 (for additional details on this unit see author’s Redcoated Ploughboys), but without the numbers to justify the establishment of three battalions, Drummond decided to amalgamate the divisions into a single battalion force. Under normal conditions, the geographic and military supply hub at Kingston would have been the natural location to gather these units for training and equipping. However, as there was already a strong garrison of regular troops stationed at Kingston, while that of York (Toronto) was still under-strength, Drummond decided to unify the separate units at York — there to be combined into the Volunteer Battalion of Incorporated Militia of Upper Canada and placed under the command of Captain William Robinson (8th [King’s] Regiment). Lieutenant General Drummond also amended the Upper Canada Militia Acts to establish a rotating conscription within the part-time embodied militia regiments, whereby a selected number of men were drafted for three months of intensive training within the ranks of the Incorporated Militia. By these measures he hoped to improve the overall standard of the militias so they could bolster the line when needed.

During this same period, at Kingston, Commodore Sir James Yeo was having challenges of his own in the planning of his new campaign for the Lakes, once the sailing season recommenced.

- His current fleet of Lake Ontario vessels was ice-bound at Kingston and were universally in need of extensive refits and repairs from their hard service during 1813.

- While General Wilkinson’s attack toward Montreal the previous autumn (for details see The Flames of War) had been thwarted, the growing scale of the war meant that the single main-supply lifeline of the St. Lawrence River would be even more vital to the British war effort and, in the event of an American resurgence, vulnerable to attack. Consequently, in addition to the existing land-based garrisons, Yeo determined that an enlarged gunboat fleet was required to guard this waterway and the convoys coming up from Lower Canada.

- The existing stocks of cut and prepared timber, fabricated ship fittings, sail canvas, ropes, blocks, and every other conceivable item necessary to outfit and maintain the existing vessels were either in short supply or entirely exhausted, leaving the official repair and preparation schedule in tatters.

- His roster of experienced sailors was barely enough to properly crew his existing fleet, let alone that of any new boats that were to be launched.

- The humiliating and strategically devastating loss of the Lake Erie fleet and the strategic imperative to regain some kind of British naval presence on the upper lakes meant that he had to seriously consider directing considerable resources and manpower away from his own reserves and (more importantly to Yeo) his direct personal control.

Beyond and above these issues was the fact that Yeo was receiving increasing numbers of reports from British agents and American deserters that the Americans were preparing a new intensive program of warship construction at Sackets Harbor. If these proved true, then by the spring the Americans would emerge with a fleet of much bigger and heavier-armed vessels that could wrest control of the essential water supply lines from Yeo’s smaller fleet, thus allowing them to simultaneously dominate Lake Erie, Lake Ontario, and the St. Lawrence River for the foreseeable future, possibly forcing the British to abandon Upper Canada entirely.

Believing this new shipbuilding threat to be paramount, and despite the severe challenges and costs involved, Yeo felt he had no alternative but to enter into an arms race with his American counterpart, Commodore Isaac Chauncey. To this end, not only did he have to design and build new warships in an impossibly short period of time, but these vessels needed to be big enough and sufficiently well-armed and crewed to compete with anything Chauncey could put into the water.

Fortunately, because Yeo’s superiors (Sir George Prevost at Quebec and Lord Bathurst in England) concurred in the need to dominate the entire Great Lakes system, Yeo was basically given a blank cheque to get the job done to control Lake Ontario. As a result, during the winter of 1813–14, Kingston became a beehive of activity. Every available local skilled tradesman was hired and set to work in an attempt to get the first batch of vessels, consisting of two frigates and four gunboats, ready for action as soon as the ice broke up. However, when this local labour force proved inadequate to the size of the task, additional workers were recruited and taken from the Niagara and York (Toronto) areas, to the detriment of their own project timetables. In addition, experienced shipworkers were brought up from Lower Canada and even the Maritimes to ensure the work got done in time. Beyond this, an entire infrastructure of workshops and warehouses were built to either fabricate, repair, or store the necessary parts and supplies that would be needed to complete the fleet for action.

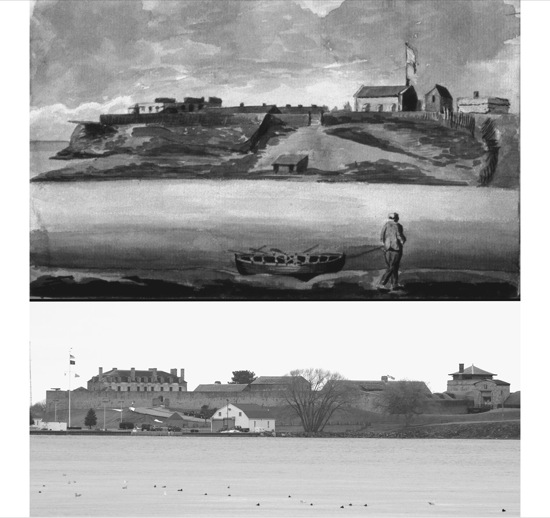

Indents for supplies to be forwarded from Lower Canada now went out by the dozens instead of singly, and supplies were requested in quantities of tons and hundreds instead of pounds and dozens. Within weeks the return shipments started to arrive in convoys of sleighs, as the St. Lawrence River remained frozen. Similarly, transfer requisitions for ships’ fittings and crews were responded to by the stripping of auxiliary naval transport vessels and even warships docked on the east coast, and their subsequent overland transportation to Kingston — along with a battalion of Royal Marines and, a relatively new military novelty, a battery of Royal Marine Artillery (Congreve Rocket) troops. As a result, the Kingston waterfront at Point Frederick turned into a naval-personnel hub and ship-production centre, the likes of which had never before been seen in British North America, away from the traditional ports of Halifax and Quebec City. While the result of these efforts soon began to rise in the form of buildings around the point and on the slipways in the shapes of two frigates, subsequently to be named the Princess Charlotte and Prince Regent, and three large gunboats Crysler, Queenston, and Niagara.

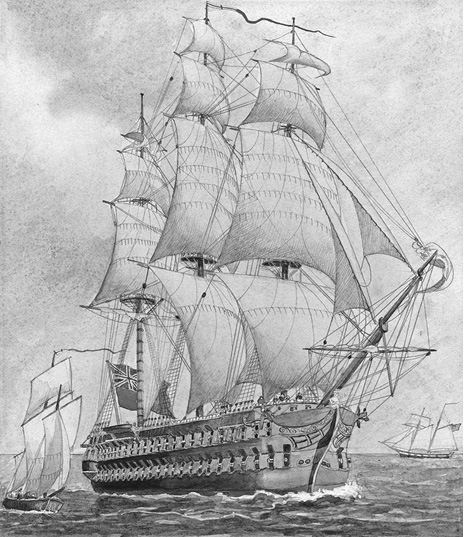

By February, with the current warships almost complete and awaiting launching in April, Yeo took the next step in his arms race by giving orders that as soon as the slipways were clear, a new behemoth warship, the largest yet to be built outside of the British yards, was to be immediately begun and completed with maximum speed. Subsequently named the St. Lawrence, this vessel was to be built with no less than three full gun decks, mounting a formidable 104 guns and allowing for the reduced requirements for the displacement and draft dimensions of a lake vessel as opposed to an ocean-going one, could be roughly compared in size to the immortal Victory of Lord Nelson fame. Unfortunately it also proved to be a black hole of a project that gobbled up valuable resources that could have been used to readily outfit and maintain the remainder of the fleet, as well as send vital supplies up to the troops fighting on the Niagara frontier.

As if this was not enough, across the Atlantic Yeo’s superiors at the Admiralty shook off their previous lethargies about the status of the Great Lakes and began to actively plan for the development of a real North American fresh-water navy for the lakes. To this end, as well as sending vastly increased volumes of supplies and manpower to the region, they also looked at ways in which they could speed up the rate of production and completion of new warships entering service. For this, they took the extraordinary decision to design, develop, fabricate, and assemble the main frames and hull parts for two frigates (Prompte and Psyche) and two brigs (Goshawk and Calibri) — in kit form at the shipyards at Chatham, England! Following which, the “frigates in frame” would be transported across the ocean to Quebec or Montreal, hauled overland past the Lachine Rapids, and then brought up the St. Lawrence to Kingston for reconstruction on the Point Frederick slipways, before being planked, decked, masted, and sparred with locally provided materials and “fitted-out” with either entirely new materials or fittings stripped off vessels in port at Quebec. By then the ships would have travelled a total distance of over 4,000 miles (6,437 kilometers)! They also drafted movement and transfer orders for almost a thousand additional seamen, which were to be implemented once the prefabricated ships were delivered and well under construction.

As the total number of existing and new vessels intended for the Great Lakes would effectively double the fleet that would come under Yeo’s command, their lordships also decided that the current arrangement (whereby Yeo and his fleet were linked to the army’s quartermaster general’s department and therefore directly under Sir George Prevost’s direction) should be amended. Consequently, in January 1814, the Admiralty established an independent naval command for Yeo to oversee. His title was elevated from “Senior Officer on the Lakes” to “Commander-in-Chief of his Majesty’s Ships and Vessels Employed on the Lakes,” while his jurisdiction not only covered the Great Lakes and Lake Champlain, but all the intervening waterways and rivers between — as well as all of the Royal Navy and associated or linked civilian shore establishments in Upper and parts of Lower Canada. In addition, as this new command would be a distinctly Royal Navy affair, it was recognized that the existing names applied to the lakes fleet sometimes duplicated those of other pre-existing vessels already on the navy’s list of vessels. Consequently, the admiralty, in its bureaucratic wisdom, unilaterally reclassified and renamed Yeo’s ships to avoid official confusion.[*6]

BRITISH LAKE ONTARIO FLEET, OFFICIAL NAME CHANGES 1814

Earl of Moria (ship-rigged sloop-of-war, built in 1805) becomes HMS Charwell

Royal George (ship-rigged sloop-of war, built in 1809) becomes HMS Niagara

Prince Regent (armed schooner, built in 1812 and previously renamed Lord Beresford in 1813) becomes HMS Netley

Sir George Prevost (ship-rigged sloop-of-war, built in 1813 and previously renamed Wolfe in 1813), becomes HMS Montreal

Lord Melville (brig-rigged sloop-of-war, built in 1813) becomes HMS Star

Sir Sydney Smith (armed schooner, built in 1808 and previously named Governor Simcoe) becomes HMS Magnet

Thus, in a single stroke of the pen, Sir George Prevost no longer had a direct subordinate under his command or control over the Lake Ontario fleet, but a separate naval establishment and independent associate commander with whom he was now expected to co-operate and coordinate the future campaigns of the war in Upper Canada — a fact that obviously did not sit well with Sir George. In a sop to Prevost’s pride and in an attempt to cut off any future argument, Lord Bathurst wrote to Prevost on January 20, 1814.

It has been determined … to extend the scale of Naval exertions; and feeling that to impose on you the conduct of Naval operations so much more extended than heretofore, would be to increase unnecessarily the responsibility of your situation, I have thought it best … to submit to the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty, the necessity of taking charge of all the Naval establishment on the lakes, and placing the fleets and dock yards there on a similar footing with His Majesty’s fleets and dock yards in other parts of the world.[7]

Unfortunately, this communication did not have its desired effect, as Prevost’s pride was distinctly hurt, resulting in a soured working relationship between Prevost and Yeo once the two commanders’ divergent opinions on how the campaigns should be conducted and respective jurisdictions of authority came into conflict. As an aside to this British naval segment, it should also be noted that at the end of February 1814 the detachment of naval personnel previously sent up from Kingston to participate in the now-cancelled Lake Erie operation were diverted north with new orders to travel overland to Georgian Bay and commence the establishment of a small gunboat dockyard facility in a naturally sheltered anchorage on the Penetanguishene inlet. However, once they finally arrived, the detachment, under the command of Lieutenant Newdigate Poyntz, R.N., found the undeveloped shoreline and rocky terrain made their assigned task almost impossible without considerably more manpower and resources. Consequently, they relocated further round Georgian Bay into the Nottawasaga River (at today’s Wasaga Beach), where the vastly better low and sandy ground permitted the groundbreaking for boat construction.

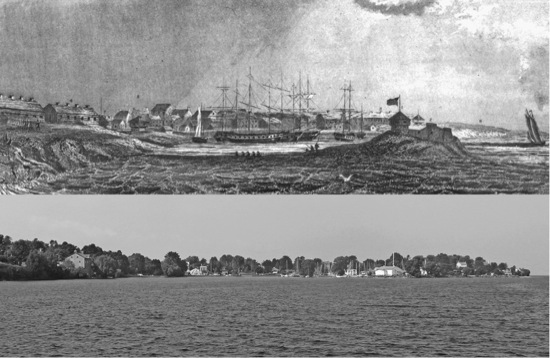

Meanwhile, during this same period and south of the border at Sackets Harbor, Commodore Isaac Chauncey had ended the 1813 shipping season by immediately beginning work on his own plans and strategies for how he would conduct his 1814 naval campaign. His main shipbuilding base had been attacked and almost overwhelmed by the British the previous May, and had only survived by good luck and the premature withdrawal of those forces by the British commander on that day, Sir George Prevost (for details see The Pendulum of War). With several of his warehouses and workshops already either destroyed or damaged (by the self-inflicted fire that had been set by the retreating American forces as part of the battle), Chauncey decided to wipe the slate clean around the harbour and erect a new infrastructure for the repair of his existing fleet (which was in a desperate need of refitting), and the construction of a number of new vessels to replace those deemed too deteriorated to be worth salvaging. To this end, Chauncey set his dockyard workforce to the task of clearing the required ground, while his associate, Master Commandant William Crane, used his regular and militia troops to begin the overhaul and revamping of the land-based fortifications and defences that were supposed to stop another landing and overland attack by the British. Chauncey also petitioned Secretary of War Armstrong for the transfer of sufficient additional regular troops from their winter quarters at French Mills to properly man these new defences.

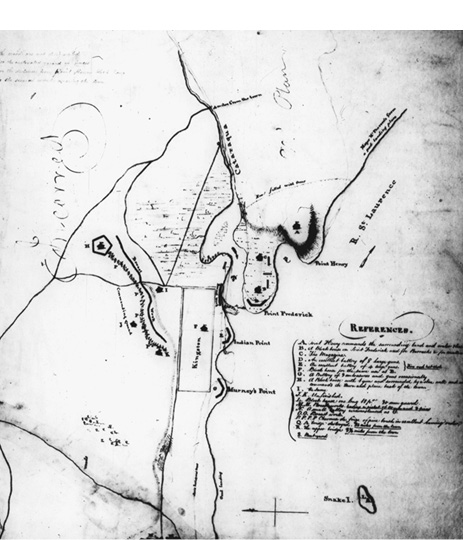

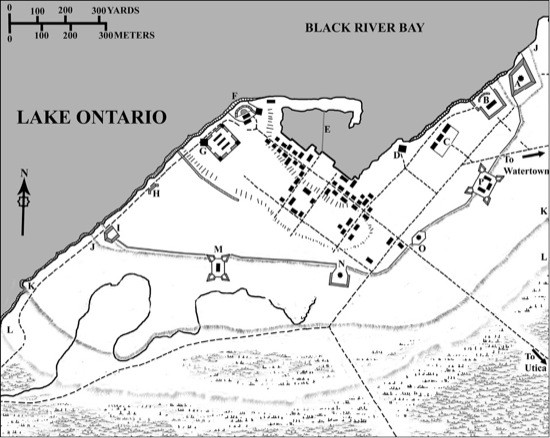

SACKETS HARBOUR DEFENCES, SPRING 1814

A Fort Pike (built partially on the site of the former Fort Volunteer)

B Pike Cantonment (comprising rebuilt elements of Fort Volunteer with an artillery position)

C Madison Barracks

D Blockhouse

E Floating pontoon bridge, connecting the dockyard to the cleared Navy Point

F Rebuilt and enlarged Fort Tompkins

G Smith Fortified Encampment

H Artillery battery and execution gallows

I Fort Mud (later renamed Fort Kentucky)

JJ Line of new perimeter defences, consisting of earthworks (connecting Fort Kentucky to Fort Virginia), picket fencing (connecting Fort Virginia to Fort Pike), and abattis (connecting all positions from Fort Kentucky to Fort Pike), running approximately along the line of the former inner line of abattis

KK Repaired and strengthened line of abattis (approximately along the line of the former middle line of abattis)

LL Former outer line of abattis (constructed February 1813, derelict and overgrown)

M Stone magazine fortification

N Fort Virginia

O Fort Chauncey

P Fort Stark

After reviewing the state of his available vessels, Chauncey ordered the worst-state vessels (Conquest, Fair American, Pert, and Julia) to be taken out of commission and scavenged for parts, while their crews were consolidated into those of the more seaworthy Sylph, Madison, and General Pike. What is important to note, however, is that as late as December 1813 nothing was actually being built by way of new warships in Sackets Harbor, nor were there any approvals forthcoming from the Washington administration for such a program, or shipbuilding supplies of any quantity on hand, even if there had been an approval. Nonetheless, the clearance work that was undertaken was sufficient to cause Yeo to begin his shipbuilding race. And if there were spies and informers for the British in Sackets Harbor, it was nothing compared to the American spies in Kingston. Consequently, Chauncey soon learned of Yeo’s building program. Determined not to be outdone and see his fleet outgunned and overmatched, Chauncey immediately contacted the secretary of the navy, William Jones, to approve a new shipbuilding program that would see an enlarged and improved fleet ready to take on Yeo in the spring. Once this approval arrived (on December 23, 1813), the floodgates were opened and Sackets Harbour became a mirror image of Kingston, as skilled tradesmen, raw and finished timbers, ships fittings, ships crews, armaments, and every other imaginable requirement were ordered up to that pre-war isolated and insignificant village. By January, the hulls of two brigs and a large frigate were already laid down on the new slipways and the dockside workshops were running around the clock to catch up with the already implemented British shipbuilding program.

Unfortunately, an unusually bad period of frigid local temperatures, coupled with blizzards and rainstorms across the eastern seaboard and Appalachian Mountains, effectively rendered the roads leading to Sackets Harbor impassable quagmires, thus delaying and impeding numerous shipments of vitally needed supplies and imperilling the construction timetables. In addition, the huge construction upheaval and massive influx of dockyard personnel (estimated at over 2,500) completely swamped the existing infrastructure of sanitation and sewage disposal within the complex. As a result, with the creeks and harbour frozen over and currents impeded, the accumulation of human effluent, combined with the detritus from animal slaughtering and food preparation, became so overpowering that sickness inevitably began to soar. By February the death rate was so high that the daily issuance of public notices and the playing of appropriate music at military funerals were suspended so as not to alarm the local population or reduce the already low morale of the troops.

In another parallel to Yeo’s plans at Kingston, Commodore Chauncey looked to raise the ante on the arms race by proposing that as soon as the new vessels were launched, work should commence on a new super-frigate that would dominate and outgun anything Yeo could produce. To further his cause, Chauncey left Sackets Harbor and journeyed to Washington to personally meet with sympathetic politicians and the secretary of the navy, William Jones. Once there, however, he found the American war administration was in a state of shambles, with political infighting and accusations of corruption and malfeasance topping the agenda of the senior American cabinet.

For example, the secretary of war, John Armstrong, held that a massive increase in the size of the army and navy were essential if the war on the Northern frontier was to be prosecuted successfully, and was making bold promises to pro-war Republicans in New York State of a winter campaign to recapture Fort Niagara from the British. On the other hand, Secretary of State James Monroe and Secretary of the Navy William Jones were favouring the adoption of proposals that had just arrived from the British government for the establishment of negotiations to produce a peace treaty. They were also openly blaming Armstrong for General Wilkinson’s failed invasion against Montreal the previous November (for details see The Flames of War) and were demanding Armstrong’s impeachment and dismissal on the grounds of his constant interference in the planning and implementation of that operation.

Caught in the middle, President James Madison was forced to both veto Armstrong’s planned Fort Niagara campaign and then support him by denying Monroe and Jones his removal from office. In addition, while Chauncey was looking for a huge outlay of funding to undertake his new building program, he found that the U.S. finances were in a state of crisis, as the war debt had spiralled out of control during the 1812 and 1813 campaigns, leaving the country close to fiscal bankruptcy. The newly appointed treasury administrator, Senator George Campbell, had also just dropped the bombshell that on top of the current war debt the already established budget for war expenditures in 1814 would exceed thirty million dollars and there was virtually no reserve or income from which it could be paid. This situation was partially Madison’s own fault, as since 1808 a series of domestically detested government legislations, commonly referred to as the Embargo and Non-Intercourse Bills, had not only interfered with American shipping and trade with Europe, but also eliminated most of the lucrative duties and taxes that had previously been the main source of American public funding (for details see The Call to Arms). Desperate to refill the nation’s coffers, Madison was now being forced into the contradictory position of advocating the adoption of legislation that would repeal the “embargo” in order to reopen and encourage trade with Europe — including Great Britain — while still fighting a war against her in British North America.

Madison also had to contend with the irrefutable fact that the favourable foreign conditions that had existed at the time of the declaration of war (namely that of Britain being fully involved with fighting what had appeared to be an unwinnable war against Napoleon Bonaparte) had now turned into a distinct likelihood that Napoleon and his empire were about to fall, potentially releasing Britain’s military machine for use against the United States. He had therefore played for time and a negotiating edge (through campaign victories by his military) by agreeing to send a delegation to Europe to begin negotiations for peace. However, upon reaching Europe the discussions could not even begin, as the two countries could not agree upon a location for these talks. The U.S. contingent therefore initially went to St. Petersburg, before transferring to London, England, and Gotheburg, Sweden, before ending up in Ghent in Belgium later in the year. In addition, once discussions began, the American delegation was supplemented by the addition of hard-line “War Hawks” and the least likely to offer or agree to any conciliatory concessions on the part of the Americans.

Despite all these issues, Chauncey got his way, and returned to Sackets Harbor in late February to find his new ships well on the way to completion and carrying the approvals for the start of not one but two super-frigates, as soon as the slipways were available.

In counterpart to the resurgence of the American naval efforts at Sackets Harbor, the entire American land forces were in the midst of a crisis affecting the very continuance of a standing army. Originally planned on paper to consist of over 58,000 troops, the American army had never topped 30,000 fit for duty during the course of the conflict thus far. In addition, while the muster rolls in January 1814 showed a force of 26,714 enlisted men, the actual duty strength was calculated at less than half that number. Furthermore, this number was about to be decimated as a result of the calendar and a contractual technicality. This circumstance had arisen because many of the currently serving troops had originally signed up for a five-year term of enlistment during the war scare of 1808 and 1809. This term of service was now ending and would soon release thousands of men from their military obligations. Similarly, the eighteen-month term soldiers who joined at the commencement of the war and twelve-month enlistees from 1813 were reaching the end of their requirements. In response, Congress was forced to pass an additional emergency financial bill boosting the (re)enlistment bounty to a staggering $124.00 per man, accompanied by a promised post-war grant of 320 acres of free land, in order to persuade the majority of the current soldiers to re-enlist and to attract new recruits.

At the same time, on the Northern frontier the remnants of Wilkinson’s army remained singularly inactive following the collapse of their campaign against Montreal. Abandoned by most of their senior and even mid-rank officers (who either took furloughs or claimed urgent business elsewhere), the rank and file were left without leadership, supplies of clothing, food, or even firewood in their singularly unhealthy and isolated winter quarters at French Mills. However, at the beginning of February 1814 the situation began to change when Brigadier General Jacob Brown was ordered to make a forced march west to Sackets Harbor with two thousand men, while Major General Wilkinson was sent back to French Mills with orders to march the bulk of the remaining troops to the east and place them in better winter quarters around Plattsburg on Lake Champlain.

Unfortunately, Wilkinson, still smarting from his failure on the St. Lawrence and the vitriolic criticism that was circulating against him, decided against simply relocating to Plattsburg, rebuilding his forces, and commencing spring operations in accordance with future directives from Washington. Instead, he mounted an attack into Lower Canada in late March at the head of some 4,000 troops — only to have his troops flounder about in heavy drifts of snow and quagmires of mud, before making an abortive attack on a negligible and isolated outpost of Canadian militia at Lacolle Mills. Unable to sweep aside even this paltry opposition, Wilkinson’s new invasion attempt collapsed and the entire column turned and retreated to the United States under a cloud of humiliation and shame.

Wilkinson’s removal from command seemed inevitable. However, unwilling to pre-empt such a humiliation by resigning, Wilkinson chose instead to demand a court of inquiry about his actions. Initially, Armstrong and the administration agreed, concluding that it would be a foregone conclusion and of no consequence how Wilkinson was removed from command, as long as he was gone. Once details started emerging about the embarrassing and incriminating testimonies that would be presented, however, their minds quickly changed and the proposed court of inquiry was just as quickly shelved, so as to avoid any revelations that could lead to the public embarrassment of government officials. Instead, Major General Wilkinson was informed that the inquiry would be suspended as subsequent events “… make it imprudent to go on as intended with an investigation into your military conduct at present…. You will choose between Philadelphia, Baltimore, or Annapolis as a place of residence. Report your arrival and await further orders.”[8]

Finally, and by no coincidence, there followed the transfer of Major General Morgan Lewis and Brigadier General John Boyd (two of the other principal players in the St. Lawrence debacle) to positions where they no longer had a part to play in the upcoming campaigns or were likely to cause trouble. Replacing these relative failures, Brigadier Generals Jacob Brown and George Izard were promoted to major general, while several regimental commanders were raised to the rank of brigadier general, including: David Bissell, Edmund Gaines, Alexander Macomb, Eleazer Ripley, Winfield Scott, and Joseph Swift.

Thus the various contenders and foes were each dealt the new hands with which they were expected to contend with for the control of the Northern frontier.