CHAPTER 3

The Winter of Discontent in the West

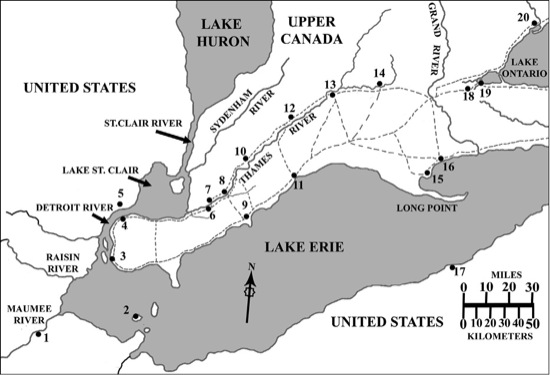

During this same period, in the western reaches of Upper Canada, the war continued unabated. This was because despite the American victories at the battles of Lake Erie (September 10, 1813) and the Thames/Moravianstown (October 5, 1813), the subsequent British victories at Crysler’s Farm (November 11, 1813) and on the Niagara frontier (December 1813) meant that neither side had enough “disposable” resources to establish a lasting firm control of this relatively distant region in western Upper Canada.

For the British, having lost control of the Detroit frontier, their new western line of defensive outposts were strategically placed to give the maximum “early warning” of any American incursions, running in a wide arc from Port Dover, Long Point, and Port Talbot, northerly to Delaware and then back northeast to Oxford (Beamsville-Ingersoll). Officially garrisoned by a rotating cadre of local militia detachments, additional “stiffening” was provided by companies of regular troops, who were periodically moved from location to location to give the impression of having a larger number of troops within the region. For the Americans, the Detroit River remained its principal front line, with temporary or isolated advance posts being established at sympathetic farmsteads along the Thames River and along the Talbot Road, leading from Amherstburg toward Long Point.

As a result, the region between became an effective no man’s land during the winter of 1813–14. That is not to say that this part of Upper Canada became peaceful. Far from it, in fact, as both sides sent reconnaissance, raiding, and supply gathering parties throughout the region in an attempt to elicit information and supplies for their own side while disrupting and harassing the enemy on the other. In addition, while the bulk of the western Native allies had either evacuated into the Burlington Heights defensive enclave or abandoned the British altogether, small bands of western warriors continued to wage guerrilla-style warfare behind the American “front line,” while being supplied with arms and ammunition by the British from their forward bases. Inevitably, detachments from all sides would occasionally come across each other and clash in brief but deadly skirmishes that ranged from a few dozen to a few hundred men in total.

The Detroit Frontier in 1814

1 Perrysburg [Fort Meigs]

2 Put-in-Bay

3 Amherstburg [Fort Malden]

4 Sandwich (Windsor)

5 Detroit

6 Thomas McCrea’s Farmstead

7 Dolsen’s Farmstead

8 Forks of the Thames (Chatham)

9 Rondeau

10 Moravianstown

11 Port Talbot

12 Battle of the Longwoods

13 Delaware

14 Oxford (Ingersoll-Beachville)

15 Long Point

16 Dover (Port Dover)

17 Presque Isle (Erie, PA)

18 Ancaster

19 Burlington Heights

20 York (Toronto) [Fort York]

While most of these engagements remain only scantily recorded, some events are more fully described. These include the clash that took place on November 13, 1813, known as the fight at Nanticoke Creek. This engagement began when a party of Upper-Canadian American sympathizers, who had previously joined the renegade regiment known as the “Canadian Volunteers,” participated in a series of American attacks upon the settlements located along the Lake Erie shoreline, looting considerable amounts of booty and supplies before beginning their journey back to their base at Buffalo. In response, a detachment of around fifty men, drawn from the 1st and 2nd Norfolk County Embodied Militia regiments and Oxford County Embodied Militia Regiment, set out in pursuit and retaliation. Tracking the culprits through the bush, they captured two of the enemy pickets and extorted the required information about the location and dispositions of the remainder of the enemy’s force. Approaching the cabin in which the enemy renegades were supposed to be sleeping, the militiamen divided into two parties, covering the front and rear to prevent the enemy’s escape. When no alarm was raised, and confident of their success, two of the Canadian officers, Lieutenant John Bostwick (1st Norfolk) and Lieutenant Jonathan Austin (2nd Norfolk), approached the cabin and pushed their luck too far by opening the cabin door, only to come face to face with a roomful of awake, alert, and armed Canadian Volunteers. Rapidly adopting a bold bluster, the two officers strode inside and demanded the renegades immediate surrender, claiming the cabin was surrounded by a vastly superior number of troops. Some of the enemy party began to comply, but when no additional loyal militia troops appeared to support Bostwick and Austin the renegades’ fear evaporated and they again grabbed their weapons before attempting to disarm the Upper-Canadian militia officers. In the ensuing scuffle, weapons were discharged, wounding Bostwick and one of the renegades. It also alerted the surrounding militiamen that the surprise had failed, causing them to rush toward the cabin, firing as they went. In reply, the “volunteers” fired back, driving off the initial charge. During the following exchange of gunfire, Bostwick and Austin were trapped inside the cabin and rapidly took cover to avoid both enemy and friendly fire. As casualties mounted within the building, some of the renegades attempted to break out of their trap by making a run for the woods. Three were killed and at least two wounded and captured, while a possible half dozen, including their leader Benajah Mallory, succeeded in escaping. Abandoned by Mallory, the remaining seventeen men inside the building immediately surrendered to the Canadian officers. However, as renegade Canadian settlers fighting on the side of the enemy, these men could expect little mercy and were thereafter placed in close confinement at York, pending the finding of trials upon the charge of treason — trials that did not take place for several months.

A further incident occurred in December, when a detachment of a dozen men from the 2nd Norfolk County Embodied Militia and seven from the Provincial Light Dragoons, all under the command of Lieutenant Henry Medcalf, were ordered to march the sixty-five miles (105 kilometers) from Dover Mills to Port Talbot. Once there, they were to scour the surrounding country for cattle being wintered in this fertile spot to deny them being taken by an American raiding party reported to be somewhere in the vicinity. Arriving at Port Talbot, Lieutenant Medcalf’s detachment was joined by nine men from the Middlesex County Embodied Militia (Lieutenant Moses Rice), who had more definite intelligence of the Americans’ whereabouts and numbers. Learning that the reported raiding party consisted of around forty American regular troops from the Twenty-Sixth Regiment, under the command of a Lieutenant Larwell, Medcalf also learned that this force was reputed to be headquartered at a known American sympathiser’s (Thomas McCrea’s) farm, some sixty miles (97 kilometers) away and within only eight miles (13 kilometers) of the mouth of the River Thames. Nonetheless, Medcalf decided on making the daring and decidedly difficult attempt to mount a surprise attack on the enemy, and to do it without any regular troops in support.

Advancing throughout the night and following day in a non-stop march across the frozen and snow-covered countryside, Medcalf’s small strike force was further enhanced en route by the addition of seven men of the Loyal Kent Volunteers (Lieutenant John McGregor). Reaching the locality of McCrea’s farmstead without being detected on the night of December 14/15, McCrea was then forced to leave some men behind due to their extreme exhaustion caused by the forced march. Just before dawn the remaining troops, totalling thirty-one men, took up positions in an arc around the farmstead with orders not to fire until ordered. Fortunately, the Americans had posted no sentries and the entire body of the enemy were inside as dawn arrived. Seizing the advantage of the moment, Medcalf called out, demanding the Americans’ surrender. In reply, shouts of alarm could be heard from within the house, followed quickly by a series of shots from the windows. Returning fire, the Canadian militiamen quickly proved the truth of their strategic advantage by shooting out the windows of the farmhouse. Shortly thereafter, a white flag was waved from the doorway and the American force of three officers and thirty-five other ranks surrendered, having suffered five wounded in the engagement.

Because of the threat of American reinforcements arriving at any moment, Medcalf ordered an immediate retreat to his own lines, while putting the American wounded (one of whom shortly thereafter died of his wounds) in the care of Thomas McCrea. Marching his captives back to Port Dover without suffering a single casualty, Medcalf and his small detachment had the distinction of having travelled overland, through the Canadian bush, in the depths of winter, a distance of no less than 250 miles (402 kilometers) in less than a week. In addition, this small capture remained the only recorded instance during the course of the war of a Canadian militia unit single-handedly capturing a regular U.S. army unit.

After this alarming nearby event, the Americans re-garrisoned the McCrea position with no less than two hundred troops and imposed oaths of future neutrality and non-aggression upon the local population — using threats of retaliation in the form of the destruction of property and the arrest, imprisonment, and possible execution of anyone suspected of assisting the British.

While these minor victories did promote pride and boost morale within Upper Canada, the increased levels of American aggression and reprisals led the British to also reinforce their outposts with additional detachments of regular troops to supplement the local militias. Unfortunately, these regular soldiers had no particular affinity or investment in the isolated and remote locations wherein they had been “dumped.” As a result, discontent and boredom sometimes led these supposed defenders to act in a manner more reminiscent of the enemy, creating a deep rift between themselves and the local communities and the militiamen they served alongside.

I propose posting [the 100th Regiment] … in the vicinity of Mr Culver’s house … from whence a small party may be detached to Oxford … Turkey Point, Mrs Ryerson’s and Dover … as that part of this corps, stationed there before … conducted itself, collectively and individually, in the most orderly and correct manner during its service there. Very widely different, I am forced to say, from the light companies of the Royals [1st (Royal Scots)] and 89th regiments, whose behaviour has been more of a plundering banditti than of British soldiers employed for the protection of the country and its inhabitants.[1]

— Drummond to Prevost,

March 5, 1814

However, not all engagements between the two sides favoured the British/Canadian allies. For example, in late January a composite detachment of over seventy men, drawn from the 1st Middlesex County Embodied Militia, the Oxford Rifles, and the 1st Kent County Embodied Militia were garrisoned at Delaware on the Thames River. Occupying local homes, the detachments were well ensconced, but their relative isolation and the winter weather led to an increasing laxity in alertness and attention to duty. As a result, a former prominent resident of Delaware and American sympathizer, Andrew Westbrook (who had previously abandoned his home and family to fight with the Americans), was able to lead a strong raiding party (drawn from the Michigan Rangers militia regiment) undetected through the surrounding countryside. On the night of January 31st/February 1st, 1814, the Americans crossed the frozen Thames River before descending on the badly defended settlement. With a full knowledge of the locations of the Canadian militia officers and their detachments, Westbrook and his American cohorts were able to overrun the defenders without significant opposition, catching most in bed asleep. Paroling the rank and file, Westbrook opted to take into captivity the principal Canadian militia officers, Captain Daniel Springer (1st Middlesex), Lieutenant Colonel Francois Baby (2nd Essex), Captain Belah B. Brigham (1st Oxford, Rifle Company), and Lieutenant John Dolsen (1st Kent). He also collected his family and as many possessions as could be transported in sleighs, before setting fire to his remaining possessions, buildings, and their contents and retreating to Detroit — while his American associates raided additional nearby barns and houses to appropriate loot and provisions for their own return trip.

In a direct response to this raid, Lieutenant George Jackson (1st [Royal Scots] Regiment) was dispatched with an official delegation to Detroit under a flag of truce to register a formal complaint for the “abduction” of the Canadian militia officers and the looting of private properties. In response, the Detroit commander, Lieutenant Colonel Butler, not only dismissed these complaints, but as he had two additional intelligence and supply gathering raids still on patrol in Upper Canada, he detained the British delegation for a number of days until both raiding parties returned to the American side of the river.

The first of these parties consisted of a combined detachment of Michigan Rangers (Captain William Gill) and Michigan Militia Dragoons (Captain Lee) numbering between eighty and a hundred men. This force had left Detroit on February 22nd with orders to forage and reconnoitre along the Thames River Valley before uniting with the second foraging detachment at a pre-arranged rendezvous point at Rondeau (southeast of the Forks of the Thames [Chatham]). Stripping the farms they passed of their livestock, grain, and anything else that came to hand, the raiders received intelligence that a detachment of Kent County Embodied Militia had been alerted to their presence and were actively on patrol. Seeking to avoid the enemy, Captain Gill moved south from the Thames Valley, toward the designated rendezvous point.

During this same period, the second, larger, raiding party had been advancing along the Talbot Road and Lake Erie shoreline under Captain Andrew Hunter Holmes, the commandant of the newly constructed American defensive fortification at Amherstburg, Fort Malden. This column had exhibited much the same behaviour as Gills’ force in forcibly “acquiring” supplies, while also being charged with the duty of making raids on the British advance post at Port Talbot. However, due to a temporary and sudden thaw in the weather, the previously firm ground had degenerated into a heavy mud that slowed the infantry and cavalry to a crawl, but entirely bogged down the heavier artillery pieces and supply wagons until it became obvious that no further advance would be possible if they remained with the column. Equally unable to retreat back to Amherstburg on their own, it was decided to temporarily abandon the guns and associated wagons in a secreted location and proceed with the rest of the mission before returning to reclaim these valuable pieces on the return leg of the journey. In addition, during their advance, Holmes’ force had captured a small group of Canadian militiamen who were travelling toward Port Talbot to rejoin their regiment. However, two of these prisoners (John Fulmer/Fuller and Alexander Wilkinson) were able to escape and fled toward Port Talbot to raise the alarm.

Linking up with Gill’s force, Holmes and Gill held a council of officers that came to the conclusion that as the British had, by now, been fully alerted by the escaped prisoners, and would expect an attack on Port Talbot, the best option for the American combined force was to double back to Gill’s route and attack the British advance position at Delaware.

THE BATTLE OF THE LONGWOODS,

MARCH 4, 1814

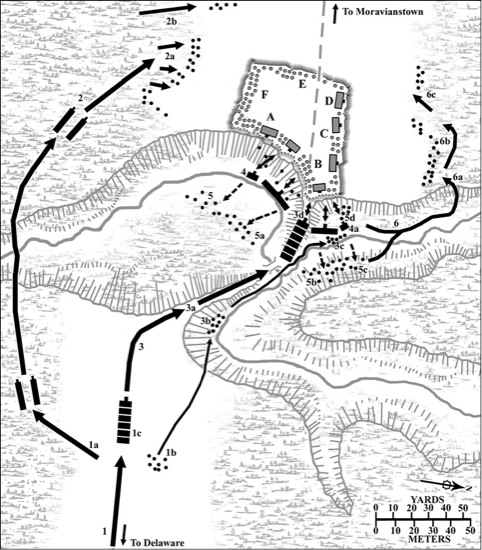

The combined American force, numbering between 180 and 200 all ranks, moved north from their rendezvous back into the Thames River Valley, picking up the main road paralleling the river at the destroyed ruins of Moravianstown (Fairfield). Turning east, they marched under weather conditions that had once again turned icy cold, accompanied by blinding snow squalls. With his men showing increasing signs of exhaustion and exposure, Holmes ordered a halt some twenty miles (32 kilometers) short of Delaware, at a point where the road dropped down into a small but steep-sided ravine on what was referred to as the Twenty-Mile Creek. On the west side of this natural obstacle, the Americans cut down timber and brushwood to erect a chest-high rectangular defensive enclave on the rear and two flanks of their new camp’s perimeter, while the natural obstacle of the steep slope of the ravine, topped by a lesser wall of abattis, was considered sufficient to defend the front face.

On the morning of March 3rd, the column had advanced a further fifteen miles (24 kilometers), when they intercepted a local settler and militiaman, George Ward (1st Kent Militia). Stripping the over seventy-year-old man to his underclothes in the frigid air, they eventually succeeded in extorting information from him that the Delaware garrison was not only composed of substantial numbers of militia but two companies of newly arrived regulars from the 1st (Royal Scots) and 89th regiments, numbering over 300 troops in all, almost double that of the American force.

Seeking to verify this intelligence, Holmes detached an advance force to reconnoitre the road ahead, only to have it run into Ward’s company of Kent militia. Following an exchange of gunfire, the Americans withdrew and reported back to Holmes. The element of surprise had now been lost, and with the prospect of facing a greatly superior number of enemy troops, not to mention the fact that a large proportion of them were regulars, Holmes ordered a wholesale retreat to their camp at the ravine — not knowing that he and his force were already under a hidden watch by men of Captain William Caldwell’s “Western Rangers,” most of whom, interestingly, are recorded as being black, or in the terms of the time “men of colour.” At the same time, at Delaware, the senior officer in command of the London District, Captain (brevetted to Lieutenant Colonel) Alexander Stewart of the 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment, was in the midst of dealing with a critical issue affecting his Native allies, who were still actively engaged in guerrilla activities behind the American lines. To support this, other tribes had been persuaded to act as couriers and transporters of weapons and ammunition. However, bad news had arrived from the Native agent Colonel Matthew Elliott.

Delaware, March 4th, 1814

Sir, I have this day had a meeting with the Natives on the subject of carrying ammunition to their friends within the American territory. The result is that they refuse to proceed with the ammunition on the ground that our regular troops do not advance further than the settlements on the River Thames, and of course would be of no use in protecting their friends in the enemy’s country. The Americans might hear of these supplies being sent to the Natives, and the consequences would be fatal, perhaps, to their whole tribes. They would, therefore, rather suffer for want of ammunition than endanger themselves or their families.[2]

Faced with this important issue and simultaneously receiving a report from Captain Caldwell that his command had “fallen in with a party of Americans,”[3] but without providing any specifics as to their numbers or dispositions, Stewart made the critical decision to personally attend to the Native issue by holding face-to-face talks with the Native leaders, while directing his second-in-command, Captain James Basden (89th Regiment) to command a strong reconnaissance force[*4] that would advance toward the reported enemy position. Stewart would then join the force once the meetings were held and the issues resolved.

Advancing from Delaware down the Longwoods road on the morning of March 4, 1813, the troops not only had to contend with the bitter cold, but also the fact that nearly a foot (30 centimeters) of new soft snow covered the previous frozen layers of snow and ice, thus creating an exhausting and treacherous surface upon which to march the twenty miles (32 kilometers) to where the enemy was reported to be still encamped.

BRITISH AND ALLIED FORCES, BATTLE OF THE LONGWOODS, MARCH 4, 1814

Meanwhile, on the east bank of the Twenty Mile Creek, Captain William Caldwell and his rangers maintained their watch across the ravine and noted the American movements. An escalating skirmish soon developed between the two forces. Significantly outnumbered, and without the cover of darkness or secrecy, Caldwell’s force began a rapid retreat up the Longwoods Road, leaving behind portions of their camp baggage. In response, Captain Holmes, being appraised of the relatively small enemy force involved and believing this constituted the bulk of the enemy before him, later recounted: “Mortified at the supposition of having retrograded from this diminutive force, I instantly commenced in pursuit with the intention of attacking Delaware before the opening of another day.”[5]

However, Holmes’ force had advanced only a matter of a few miles before the mounted advance guard returned in haste, bearing reports that a sizeable British force was directly ahead and appeared to be deploying for battle. Believing he had been deliberately tricked into leaving his strongpoint for the purpose of forcing him to fight in the open with a significant numerical disadvantage, Holmes ordered another immediate retreat. Arriving back at their encampment, some of the detachment’s officers advocated a further retreat and abandonment of the entire expedition, while others called for a “victory or death” stand. Deciding to hold the position, Holmes dispatched a party of his sickest men back toward Detroit before ordering the strengthening of the breastworks against attack and deploying his limited force.[*6]

AMERICAN DISPOSITIONS, BATTLE OF THE LONGWOODS, MARCH 4, 1814

Front/Ravine Flank (east face)

Left Flank (north face)

Right Flank (south face)

Rear Flank (west face)

THE BATTLE OF THE LONGWOODS, MARCH 4, 1814

Advancing down the road from Delaware, Captain Basden linked up with Caldwell’s detachment and then pressed on with his augmented force of around 250 regulars, militia, and Native allies, reaching the vicinity of the Twenty Mile Creek in the late afternoon. As the sun was close to setting and with no sign of Lieutenant Colonel Stewart arriving to take over command and direct operations, Basden was left with the difficult options of:

- Making an immediate attack with a force of exhausted troops upon an enemy of indeterminate numbers and situated in a prepared defensive position.

- Encamping his own force within the immediate vicinity of that same enemy force and risking them making a nighttime sortie on his encampment.

- Retiring a few miles to encamp with more safety, but with the chance that his quarry would then evade his pickets and escape down the Longwoods Road under the cover of darkness.

Deciding to strike while the opportunity of proximity and daylight still existed, Basden undertook no detailed reconnaissance of the enemy dispositions before making his initial deployments. Unfortunately, in the aftermath of this action, the report made by Captain Basden was delayed by nearly a week, the result of his having been wounded. Instead, a second report, made only the day after the event by Lieutenant Colonel Stewart, became the official version of events, but contains contradictory details on the specific flanks upon which the militia and Native contingents were deployed. As a result, I have chosen to accept the report of the officer in command and on the spot for my version of events — although those who prefer Stewart’s second-hand account simply need to “mirror” the flanking deployments, without changing the outcome. According to Basden’s report:

On approaching the place where the enemy had been before seen, it was observed that by the smoke and some noise that they were occupying the same ground. I therefore made my dispositions for an immediate attack, it growing late, they were posted on the opposite side of a ravine, on a high bank close to the road, and I thought I could perceive a slight brushwood fence, thrown up as I presumed to obstruct the road.[7]

Deeming this obstacle as representing only a moderate hindrance, he decided to make a direct frontal column attack with his regulars that would break through directly into the enemy’s encampment. At the same time, his militia force would move round on the enemy’s flank:

The Kent Volunteers with the Rangers I directed to file through the woods to my left, and by making an extensive circle, they were to post themselves in rear of the enemy, get as near as possible, not to fire a shot, but to sound a bugle whenever the position was properly secured and they were prepared to advance.[8]

Similarly, his Native detachment, which at this last minute was augmented by some additional late arrivals, was to be “stationed to flank my right, and advance with the main body.”[9] When the call was heard, the regulars, led by an advance party from the 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment advanced down the ravine in a solid column of men, probably five to eight men across and from twenty to thirty deep. While this human “battering ram” had the disadvantage of reducing the number of men who could fire at the enemy, it had the advantage of maintaining its solidity and inertia in an attack of this kind, and despite taking the inevitable casualties could have been expected to punch its way through a relatively thin line of opposing troops, especially that of militia, thus breaking the American formation. What Basden had not taken into consideration was that, in addition to the enemy’s troops formed directly along the top of the ravine, there were additional formations on either flank, who could detach men to bolster the front flank if theirs was not under attack. Beyond this, while the breastwork obstructions facing the ravine may not have been as formidable as those on the flanks and rear, the steep slope of the ravine had a natural sub-surface of ice and compacted snow, which according to some accounts had been enhanced by the Americans by pouring water down the slope to freeze in the frigid air. As a result, the column’s impetus on the downward trek was rapidly eliminated and disrupted as it tried to force its way up the ice-bound rise, with men unable to gain any traction in their leather-soled boots. Furthermore, as a solid mass of men it represented a perfect unmissable target for the American soldiers, only a matter of yards away and producing the heaviest volume of firing that could be brought to bear. According to the American commander, Holmes:

The enemy threw his militia and Natives across the ravine above the road and commenced an action with bugles…. His regulars at the same time charged down the road from the opposite heights, crossed the bridge, charged up the heights we occupied, within twenty steps of the American line and against the most destructive fire. But his front section was shot to pieces. Those who followed were much thinned and wounded. His officers were soon cut down…. He therefore abandoned the charge and took cover in the woods at diffused order, between fifteen and twenty paces of our line, and placed all hope upon his ammunition.[10]

While Basden recorded:

The enemy commenced their fire immediately upon our appearance, and when the head of the column had proceeded a short distance down the hill, the firing from them [the Americans] was so severe as to occasion a check. They [the column] however, instantly cheered and rushed on, making for the road on the opposite side, with the intention of carrying this fence. However, this was found impossible, the ascent being so steep and slippery.[11]

Taking increasing numbers of casualties in this close-packed formation, Basden attempted to deploy his sections into a line, with the 1st (Royal Scots) on the left and 89th on the right. By this he hoped to reduce his casualties and extend the width of his attack. Unfortunately, the rough and slippery ground bordering the creek disrupted any coherent linear formation and each time an advance was attempted by the separate sections, the slippery incline destroyed any cohesion as men slid back or fell, while those who succeeded in advancing simply became more prominent targets for the American guns and were shot down.

Unable to break through as a body, most of the attackers fell back across the creek and began firing from the cover of fallen trees scattered across the slope of the ravine, others, however, remained just below the American position, resulting in the aforementioned stalemate of firing at ranges of sometimes less than twenty yards (18 meters).

Looking to break the impasse, Basden collected whatever men he could locate and directed them to “follow me and I moved in the ravine to the right for some distance under an uncommon severe fire.”[12] Reaching a point he thought well beyond the left end of the American line, Basden believed his force of regulars and Natives could climb the embankment and, after forming on the open ground above, attack the enemy on a vulnerable open flank. Instead, “on ascending and gaining the top of the bank, I was very much surprised to observe another face of a work.”[13] Immediately upon the appearance of this new target, the American troops lining the American left flank (north face), namely the Twenty-Sixth Vermont Militia and Twenty-Seventh New York State Militia, opened fire. In response, Basden stated:

I placed the men in extended order under cover of the trees, and the action was kept up with great vigour till dusk…. I now determined to send to the point on the top of the hill … for more men to strengthen the party I had then with me, and upon their arrival, to storm the enemy’s position agreeably to my first intention.[14]

However, no such attack took place as “At this instant I received a severe wound in my thigh, and was under the necessity of going to the rear.”[15]

Command of the disorganized British force now devolved upon Ensign Francis Miles (89th Regiment) who, not having any idea how the militia forces on the other side of the American position were faring (in fact, they too had come under heavy American fire and been reduced to sniping from the surrounding wood line), but knowing his own force was effectively blockaded, made no additional attempts to close with the enemy in the deepening darkness. Instead, the various British and Canadian detachments broke off and retired to the east side of the ravine, just in time to meet up with Lieutenant Colonel Stewart and a detachment of reserve troops, who had just hurried up the last few miles of their exhausting march in response to the sounds of battle echoing across the frozen countryside. Unable to see or assess the American positions or numbers in the darkness, and with his own force clearly severely traumatized and reduced, Stewart ordered a retreat to the Fourteen Mile Creek, there to remain on the alert throughout the night before assessing the tactical situation in the light of day.

Looking to mitigate the serious defeat his troops had suffered whilst he was absent from command, Stewart immediately penned his version of the day’s events (including the reversal of the flanks upon which the militias and Natives served) and an initial casualty list,[*16] before dispatching it to Major General Riall at Burlington Heights.

ESTIMATE OF CASUALTIES, BATTLE OF THE LONGWOODS, MARCH 4, 1814

British

Regulars

Loyal Kent Volunteers

American

However, following this, he failed to maintain any effective rearguard watch on the Americans. As a result, despite receiving word that the enemy were apparently retreating, he made no effort to re-establish contact until the following morning, when his scouts found Holmes’ camp abandoned:

Sir — I have to acquaint you that the enemy retreated precipiantly from their position about 8 o’clock on the night of the 4th instant down the River Thames. As the service for which the advance of the troops was intended has been frustrated by the Natives refusing to proceed with the ammunition, and no probability of our being able to come up with the enemy, as they had gained twelve hours’ march of us, I have withdrawn the troops to this place [Delaware] where we will remain waiting your further instructions.[17]

—Stewart to Riall, March 6, 1814

In fact, following the engagement, and after spirited discussion amongst the various American officers as to their tactical position and fighting capability due to casualties, they agreed to make an immediate silent retreat under the cover of the night, allowing them to be well back on their march to Detroit before Stewart reacted to their departure. Upon his return to Detroit and submitting his casualty report,[*18] Holmes came under some criticism for retreating, to which he made the following rebuttal in a report to Lieutenant Colonel Butler.

I did not pursue for the following reasons:

- We had triumphed against numbers and discipline and were therefore under no obligation of honor to incur additional hazard.

- … the enemy were still superior [in numbers] and the night would have insured success to ambuscade.

- The enemy’s bugle sounded close upon the opposite heights. If then we pursued, we must have passed over to him as he did to us, because the creek could be passed on horseback at no other point, and the troops, being fatigued and frost bitten, their shoes cut to pieces by frozen ground, it was not possible to pursue on foot.[19]

In the aftermath of this small but decisive engagement, the Americans pushed forward yet another force of around 500 men up the Thames Valley around the middle of March, advancing as far as the upper reaches of the Thames and once more raiding farmsteads. They also sought to recover the guns and wagons previously hidden by Holmes’ column, but without success. This failure was simply because in the intervening period three men from the Loyal Essex Volunteers militia, who had escaped from being held at Amherstburg and were returning to Port Talbot, had found the hidden stash. Taking what supplies were useful, the militiamen reached safety and then returned with a party of their fellow militiamen; whereupon they disabled the wagons by removing their wheels, burned the artillery carriages, and hauled off the cannon barrels and ammunition, hiding them deep in the nearby Black Ash Swamp, where they supposedly remained to the end of the war. Nonetheless, news of this latest American incursion alarmed Major General Riall, who decided to abandon his advanced positions in the London district and concentrate his forces at Oxford, with other detachments stationed at Port Talbot, Long Point, Turkey Point, Dover, and Burford. As a result, the intervening region was left fully exposed to future American incursions. Fortunately the intermittent thaws with the onset of spring degenerated the roads to an even worse state of repair than normal, forcing both sides to suspend their offensive activities until the weather and road conditions improved enough for campaigning to recommence.