CHAPTER 6

The Raid on Oswego, May 5–6, 1814

The target of the British sortie was the old British defensive depot officially designated as Fort Ontario, but known generally as Fort Oswego. Built in 1759 to replace an earlier structure destroyed during the Seven Years War between Britain and France, Fort Oswego commanded the strategic entrance to the Oswego River and a line of communications leading south to the Mohawk Valley. It was through this corridor that the great majority of the supplies destined for Sackets Harbor were being channelled and its elimination would, in the British commanders’ views, be of significant value in throttling the development of Chauncey’s warships at Sackets Harbor.

Prior to the current war, the depot and fort had been an isolated and insignificant outpost, and was allowed to deteriorate to a state of dereliction. Once the war began the warehouses had been repaired, but the fort remained an effective ruin and the garrison of troops little more than a watch guard. Now, in 1814, with the huge building program taking place at Sackets Harbor, Oswego took on new significance as a focal point for the transfer of supplies. Consequently, by the end of April the existing garrison of twenty-five seamen (Lieutenant George Pearce) had been supplemented by a force of around 300 artillerists from the Third Artillery Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel George Mitchell). Unfortunately, despite their strong numbers, they brought no field pieces with them, as they were expected to use the ones listed as being on-site. However, upon arrival these were found to be only five derelict pieces, without carriages and with three having had their trunnions (elevating swivels) sawn off (to designate them as condemned). Furthermore, the supposed defensive fortifications on the hilltop were effectively useless, with the wooden picket walls mainly rotted away and collapsed into the ditch.

While repairing the five guns and beginning temporary repairs to the picketing, the American garrison was alarmed when, shortly after dawn on May 5th, a flotilla of ships and gunboats, all towing longboats and bateaux, were seen approaching from the north. Knowing the American fleet was still in harbour, the titular garrison commander, Commandant Melancthon Woolsey, quickly identified them as British and sent riders into the surrounding communities to muster and bring back as many militia that could be assembled before the inevitable attack descended. He also issued orders that the small schooners Growler and Penelope, moored at the wharf below the fort, be prepared to be scuttled if necessary. Curiously, although there was a surplus of artillerymen available and no less than twelve large cannon and a wealth of shot and powder immediately on hand that could be jury-rigged for action, even if it was only for a single round, these guns were not brought into service. Thus, apart from erecting a number of tents on the flat ground below the fort to give the impression that there was an enhanced number in the defenders force, nothing was done to enhance the defences of the position. Instead, these valuable guns and shot were ordered dumped into the Oswego River, while the surplus artillerymen were designated for duty as infantrymen.

Aboard the arriving flotilla, preparations were being made to land by noon. The plan was for Lieutenant Colonel Fischer to lead the initial landing force — composed of two companies of his De Watteville Regiment, some Royal Marines, and the detachment of the Glengarry Light Infantry — to a position on the left (east) of the fort and attack uphill from there. At the same time, Lieutenant Colonel Malcolm would lead the remaining bulk of the 2nd Battalion of Royal Marines, backed by 200 volunteer sailors under Captain Mulcaster, in a landing to the right (west) of the fort, thus splitting the enemy’s firepower. The remaining four companies of De Wattevilles and artillery were to remain onboard the fleet and act as a mobile reserve or secondary landing column if required.

To commence the operation, a number of the shallow-draft gunboats were sent inshore with orders to bombard the enemy positions and draw retaliatory fire, so as to reveal the American positions. One of the derelict American guns mounted at the fort burst its barrel when fired, leaving the fort with only four guns (a 4-pounder and 9-pounder facing the lake and two 4-pounders facing the inland flank). Following this initial foray, the landing craft began loading late in the afternoon, with a projected landing to take place before sunset. However, within the space of a couple of hours the weather had changed dramatically as a storm front blew in, whipping up a wind that threatened to drive the entire fleet onto the nearby shore and creating decidedly choppy conditions in which the already overloaded small boats and bateaux were in serious danger of being swamped. Left with little alternative if he was to safeguard his entire brand-new fleet, Yeo was forced to call off the landing, order the troops re-embarked, and then see the fleet weigh anchor and reposition itself further offshore, where they could manoeuvre without the danger of being wrecked. So rapidly was this done and so imminent was the danger perceived to be, that once the troops were re-boarded at least four of the bateaux and boats were cast adrift instead of being secured (and thereby possibly becoming a floating anchor to their respective boats if they became swamped in the expected storm).

Despite being given this unexpected and heaven-sent reprieve, the Americans made little additional effort to improve their defensive positions or remove any of the vital supplies. Fortunately, as the night passed, detachments of around 200 local militia arrived to supplement the garrison’s numbers and were posted alongside the detachments of artillery men acting as infantry on the low wooded ground to the east of the fort, near the tent encampment, as it was anticipated that this was where the enemy would land.

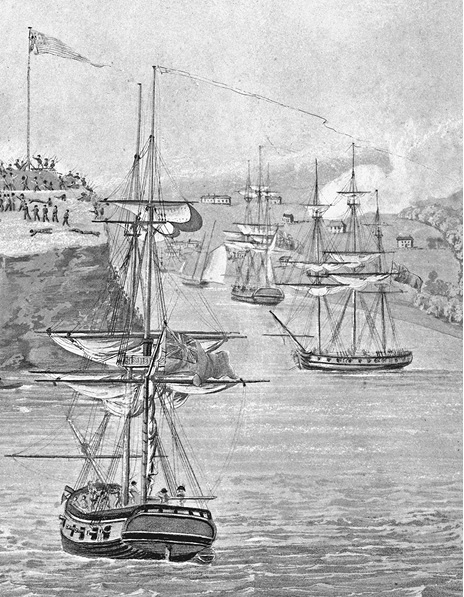

Later that night the threat of the storm had passed, but due to headwinds the fleet took some time to tack up to its proper stations. Once there, the landing boats were secured alongside and the first contingents of men clambered down the ships sides in the pre-dawn darkness. At dawn the attack recommenced, with the fleet beginning an intensive bombardment of the identified American positions that did no real damage nor inflicted significant casualties. However, it did succeed in persuading many of the just-arrived militia that this was no place to remain, causing almost the entire contingent to desert forthwith. Meanwhile, offshore the continuing choppy conditions and brisk wind slowed the completion of the loading of the boats until well after noon, forcing many of the men who had boarded first to be tossed about for hours on end. Finally, shortly before 2:00 p.m., the two flotillas of boats pulled for the shore, with Fischer’s contingent aiming for the American tented encampment and apparently flat shoreline to the east of the fort. What was not taken into account, however, was that this position had an extensive and uneven shoal of rocks just offshore, below the surface of the water. This impediment grounded many of the heavily laden boats and bateaux well away from the beach, forcing their troops to jump into the water and flounder ashore while under fire. In addition, due to the broken nature of the lakebed, the shallows were intermingled with deeper stretches of water that dunked many a man who unwarily stepped into them — soaking and ruining their cartridge boxes of ammunition. Reaching the shore, the landed troops began to form their company lines and assess the damage done to their supply of ammunition (while still under fire). After distributing the available usable ammunition it was discovered that each man would only have a handful of shots to attack with. For Fischer this posed a dilemma, as their reserve ammunition was to have been brought in the succeeding wave of boats and would take some time to arrive, while the other landing force was already approaching its landing zone off to the right and directly below the fort. If he delayed his own advance to obtain a resupply of ammunition, Fischer knew that Malcolm’s Marines and Mulcaster’s naval volunteers would take the full brunt of the American fire from the fort. He therefore made the difficult decision to give as many of the usable cartridges as could be spared to the detachment of around fifty Glengarry Light Infantry that was with his landing force. They were then ordered to move off to the left and enter the woods from which the Americans were firing and, without knowing the strength of the enemy before them (somewhere between one and two hundred men), to clear that ground of any opposition. At the same time, the remaining troops from the De Watteville Regiment would advance toward the fort, armed solely with the bayonets that were now fixed on the ends of their otherwise-useless muskets.

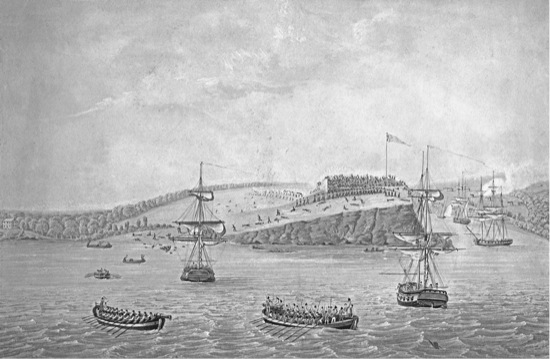

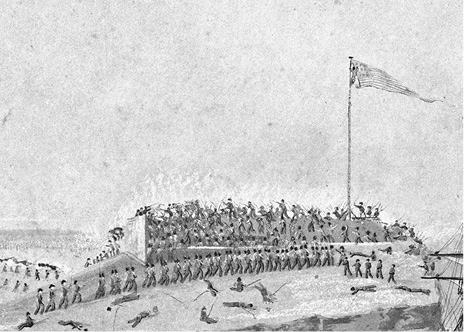

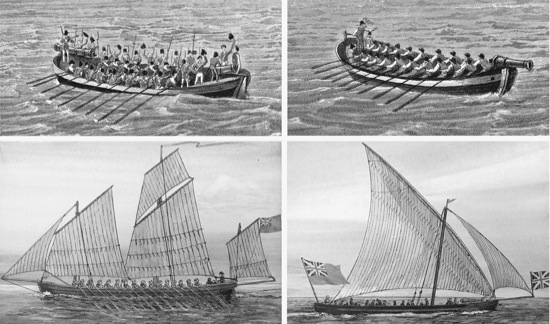

The Storming of Fort Oswego by 2nd Battalion Royal Marines and a party of Seamen, 15m past Twelve at noon

Meanwhile, on the right of the British landing, the Marines and naval volunteers landed against minimal resistance and advanced up the steeper slope of the hillside, only to come up against an increasing level of American fire as men retreating from the eastern flank reached the relative security of the fort and bolstered the defensive position. Despite this, the poor state of the fort’s structural defences and woefully under-gunned garrison left the issue in little doubt and, despite putting up a strong defence, once the British Marines and sailors succeeded in breaching the fort’s earthwork perimeter, Mitchell was forced to order the evacuation and retreat of his remaining forces into the nearby woods.

The British had won the day, but at a relatively heavy cost.[*1] They then began the principal reason for their attack by stripping the adjacent warehouses of whatever supplies could be transported and destroying the remainder. They also refloated the scuttled boats and towed them out as prizes of war. However, the volume of materiel found at the port did not match what was expected if the intelligence reports were correct. Believing that the Americans may have removed and hidden the missing items during the British fleet’s unexpected withdrawal, Drummond had a search made of the surrounding forest, while Yeo questioned some of the prisoners to gain the required information, but in both cases to no avail. In fact, the greater bulk of the supplies were still in transit and were only a few miles upriver, stored at the American depots at Fredericksburg and Three River Point. However, without knowing of these supplies, Yeo and Drummond, while recognizing that they had at least put a dent in Chauncey’s program of construction, were aware that the victory could rightly be criticized for suffering such heavy casualties against a relatively weak garrison position and the far fewer-than-expected supplies gained. It would also bring into question the certainty of a victory in any future attack against Sackets Harbor, where the defences were substantially stronger and the garrison vastly greater. As a result, once they had returned to Kingston to a hero’s welcome on May 8th, both commanders submitted reports that enhanced the state and strengths of the American defences, exaggerated their defender’s numbers, and overestimated the significance of the impact it would have upon the American building efforts at Sackets Harbor. However, they need not have worried about criticism from Prevost, as he was occupied with the deteriorating prospects of concluding an armistice with the Americans at Plattsburg.

There, Prevost’s representative, Colonel Baynes, had been fully expecting to meet with Brigadier General Winder. He had also come with a full brief of terms and proposals that would have seen the armistice applied across the entire theatre of war on the Northern frontier, be indefinite in length, and subject to expiry only after a fifty-day notice of the failure of the negotiations in Europe or an equivalent notice from their respective governments. However, the designated American representative, Brigadier General Winder, did not turn up. Instead, the subordinate American representative, Colonel Ninian Pinkney, arrived with the contradictory claims that while he was empowered to discuss the imposition of restrictions upon British warships operating off the eastern seaboard (something over which Prevost had no jurisdiction), he had no authority to negotiate anything on land other than a local ceasefire and termination on a twenty-day notice. In fact, he considered himself so restricted in his jurisdiction in that sphere that he refused to open the official dispatch pouch from Washington (containing instructions for the negotiations), because it was addressed to Brigadier General Winder!

British Troops

Naval Ratings

Royal Marines

American

N.B.

Unable to make any headway and believing that he was simply being stalled, Baynes returned to report the breakdown of negotiations to Prevost. In the aftermath of having Drummond and Yeo’s warnings seemingly proved true, it is possible to conclude that by writing the following letter, Prevost may have looked to recover some of his authority in the face of their unauthorized venture (while at the same time covering himself in case of subsequent criticism for not supporting their proposed attack on Sackets Harbor), by retroactively claiming to have approved the expedition to Oswego and then establishing a documented new tone and position on the question of sending troops into Upper Canada.

My letter to you of the same date [May 3rd] will have anticipated your wishes by conveying my approval of that measure. I cannot at this moment supply you with the 800 effective men you deem necessary to enable you to attempt, by a combined operation, the destruction of the enemy’s fleet and stores at Sackets Harbor, and it will depend upon the force which His Majesty’s Government may place at my disposal from England during the next month, whether the seat of war may be transferred to the enemy’s possessions contiguous to Upper Canada, or whether, as at present is the case, I shall be obliged to retain the whole of the troops I have in Lower Canada for its defence.[2]

—Prevost to Drummond,

May 7, 1813

At the same time, on the American side of the lake the loss of Oswego and, more importantly, the loss of some of the important, guns, fittings, and supplies destined for the new vessels at Sackets Harbor, caused Commodore Chauncey to react with exaggerated measures for the protection of his additional deliveries. In the short-term, a strong body of troops were transferred from Sackets Harbor to Oswego with instructions to fortify the position and then salvage as much as possible from what had been left behind or missed by the British, and see it taken upriver to Fredericksburg where it would join the supplies at that depot — which, despite the logistical and transport difficulties and inevitable damages and loss of time involved, were now to be transported overland to Sackets Harbor. He also ordered the acceleration of his already strained program of building. The Superior had been launched on May 1st, and was being fitted-out with every piece of equipment that could be found, scrounged, or expropriated from the warehouses and other vessels in the harbour, while the frames and planking for the new vessel Mohawk were being constructed in a round-the-clock schedule. There are also indications that he was deeply concerned about the security of his base, as the British had already made two commando-style attempts to damage the Superior during the course of her construction and one to sink her immediately after her launching. In the first instance, on the night of April 20–21, a single longboat had evaded the patrolling American boat pickets and landed a small party of men. Reaching the ship, they had intended to start a fire underneath her but, due to the patrolling guards, were detected and forced to withdraw before they were able to implement their plan. The second, more organized, attempt had taken place on the night of April 25–26, when three boats made an attempt to sneak into the basin — only to be detected, challenged, and fired upon by the boat pickets. As two of these boats were packed with barrels of black powder and rigged with fuses, their crews had wisely withdrawn to avoid being blown up and “hoist on their own petard.” These deadly cargos were subsequently found by American patrols, abandoned a short distance up the lake. In addition, the third boat had also withdrawn, but interestingly had obviously been fitted for use as a diversion or separate attack, as it contained a launching frame for the firing of Congreve rockets from the deck of the boat and was manned by the Royal Marine artillery detachment. The final, and obviously desperate, attempt had taken place immediately after the launching, when a detachment of troops attempted to land on the night of May 2–3, but were unable to penetrate the harbour perimeter guards. After hiding throughout the day in the dense woods that lined the lake and being eaten alive by the even denser clouds of mosquitoes that infested the coastal underbrush, they had made a further attempt on the night of May 3–4, but were detected and forced to abandon the entire endeavour.

Looking to emerge with his newly strengthened fleet as soon as the Superior was fully fitted out, Chauncey had found the aforementioned overland transportation of the largest pieces, especially the cannon barrels, was impractical, given the state of the intervening roads. Consequently, he was forced to re-establish the use of boats (that would skirt the shores and move at night) to bring up these heavy supplies. However, he saw this solution temporarily thwarted when the larger vessels of Yeo’s fleet, accompanied by a flotilla of gunboats, reappeared off the harbour on May 19th, thereby establishing a blockade of the intervening lakeside passage (the remaining vessels being dispatched in accordance with Yeo and Drummond’s prior agreement to transport reinforcements and supplies up the lake to the Niagara frontier).

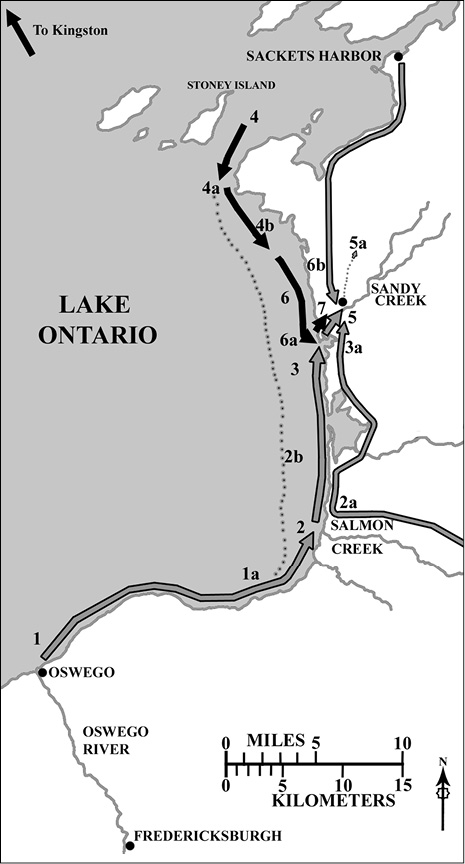

Suffering a recurrence of a previous illness that prevented his actively taking command of his fleet, Chauncey was equally determined not to see one of his subordinates gain a victory that should have been his to claim. He therefore ignored the calls from his captains to emerge with those ships already at his disposal in order to challenge the limited enemy squadron offshore. On the other hand, desperate to receive his armaments, Chauncey authorized Commandant Woolsey at Fredericksburg to make a convoy delivery by boats if any opportunity presented itself. This chance seemingly occurred on May 26th, when the British fleet was seen moving off station and up the lake. Dispatching immediate orders for the shipment to commence, Chauncey was later forced to send a message to abort when the enemy fleet reappeared. However, his countermand arrived too late, as the sixteen-boat convoy, under Woolsey, had already sailed on the 28th. Creeping up the Lake Ontario shoreline during the night, the convoy met up with a party of around 120 Oneida warriors, who were sent to act as an additional shore-based guard to supplement the 130 riflemen (Major Daniel Appling) onboard the boats. Unfortunately, some of the boats subsequently became separated in the darkness, with one falling into the hands of the re-established British blockade ships the following day (May 29th). Alerted to this American attempt, the British determined to intercept the rest of Woolsey’s convoy by dispatching a strong flotilla of three gunboats and four bateaux carrying over 200 sailors and Royal Marines (Captain Stephen Popham, R.N.) to locate and capture or destroy the enemy convoy.

Meanwhile, fearing the worst from the loss of the boat, Woolsey had taken refuge and set up a strong defensive position with his boats, well up the Sandy Creek waterway, some ten miles south of Sackets Harbor. He then notified Chauncey of his situation. In response, Chauncey had Brown send a detachment of troops that arrived the following day, only moments before Popham had ordered his flotilla (against Yeo’s specific warnings) to enter the creek in pursuit — only to find itself manoeuvring upstream in ever-more restricted navigational conditions. As a result, Popham and his flotilla fell into the ambush laid by Woolsey. After losing eighteen killed and fifty wounded, and with his boats incapable of turning or retreating, Popham was forced to surrender his entire contingent. By this, not only did Yeo lose the boats, but also over 200 of his limited number of valuable ships crews and marines. Consequently, with this huge loss of manpower and shipping, Yeo felt he could no longer maintain the blockade and ordered the fleet return to Kingston, freeing the Americans to resume their building program. Yeo also made the decision that as the Americans would now be able to complete their super-frigates unimpeded, which would result in their ships outclassing the firepower of anything he had to counter with, his only option was to keep the bulk of his fleet safely in port till his own super ship, the St. Lawrence, was complete and able to help his fleet to take on the Americans. Even Lieutenant General Drummond saw the sense in this and backed Yeo’s decision:

It appearing, however, from your [last] letter that the Enemy’s squadron, including the new ship (Superior) and Brigs, is now ready for sea, it is evident the blockade has not had all the effect to which we looked, and moreover, that it can no longer be maintained, without risquing an action with a squadron quite equal, if not superior to that under your command, and under circumstances on our part of decided disadvantage…. It follows, therefore, … that there exists at present no motive or object connected with the security of this Province which can make it necessary for you to act otherwise than cautiously on the defensive (but at the same time closely watching all their movements) until the moment arrives, when by the large Ship now on the stocks, you may bring the naval contest on this Lake fairly to issue, or by a powerful combined expedition (if the Enemy, is as probable, should decline meeting you on the Lake) we may attack and destroy him in his stronghold.[3]

— Drummond to Yeo, June 6, 1813

The tide had fairly turned for the British and it was the Americans’ turn to dictate the course of the naval conflict on Lake Ontario. Chauncey, although still ailing and reportedly becoming increasingly tetchy about “his” fleet and how it was to be deployed, did hold discussions with Major General Jacob Brown about future combined operations and mutually supporting activities — once the force at Buffalo was put into action and the main campaign on the Niagara began. Unfortunately, while Commodore Chauncey saw these discussions as nothing more than theoretical discussions of the two forces acting in an equal co-operation for their mutual benefit, Major General Brown took them as firm commitments of Yeo’s agreement and verbal contract to act in support of Brown’s army on the Niagara — especially as Brown now held the firm conviction that as the danger at Sackets Harbor had passed, it was time for him to leave and return to take up his position at the head of his army on the Niagara frontier. Although what he found upon his return may not have been the warm welcome he had been anticipating.