CHAPTER 7

Building a New Army

Following Major General Jacob Brown’s departure from Buffalo for Sackets Harbor in April, the on-site disciplining and training of the American troops composing the Left Division was taken in hand under the personal direction of Brigadier General Winfield Scott. In later years, the heroic tale of Scott single-handedly whipping raw recruits into a disciplined fighting force by the use of a tattered drill book became the stuff of legend — most of it propagated by Scott himself. But more recent studies have shown that in reality, most of the troops and junior officers serving in this army at the time had already undergone considerable training and battlefield service during the previous eighteen months of war. What is beyond doubt, however, is that at no previous time had these troops been subject to the intensity and scope of training that was about to commence under the eagle eye of “Fuss and Feathers,” Winfield Scott.

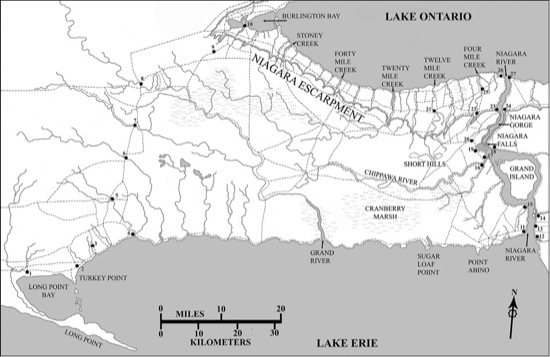

THE NIAGARA FRONTIER

Locations along the proposed American attack route from Long Point to Burlington Heights

1. Long Point (Port Rowan area)

2. Turkey Point

3. Dover (Port Dover)

4. Nanticoke

5. Union Mills (Simcoe)

6. Sovereign’s Mills (Waterford)

7. Malcolm’s Mill (Oakland)

8. Brantford

9. Ancaster

10. Burlington Heights

Locations along the actual American invasion route following the Niagara River

11. Fort Erie

12. Buffalo

13. Black Rock

14. Scajaquada Creek Navy Yard

15. Frenchman’s Creek

16. Weishoun’s Point

17. Chippawa Fortifications

18. Fort Schlosser

19. Bridgewater

20. Lundy’s Lane/Portage Road crossroad

21. Shipman’s Corners (St. Catharines)

22. St. Davids

23. Queenston

24. Lewiston

25. Crossroads (Virgil)

26. Fort Mississauga/Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake)/Fort George

27. Fort Niagara

Day after day, for almost two months, the men of this new “model” army were put through every command in the established drill manual for up to ten hours each day. Commencing at the crack of dawn, company and section drills took up the mornings, while regimental and brigade manoeuvres consumed the afternoons and evenings, with only brief intervals to permit the men to rest and eat. Nor were the officers exempted from these rigours, as Scott pressed the point home that it was essential to create a military force that could fight a European army in a European manner and simultaneously undertake the difficulties of campaign without degenerating into an armed mob. Fundamental to this professional attitude was the strict enforcement of discipline, duties, and responsibilities upon both the officers and men — to the point where of twenty-six men held under arrest for various infractions nine were officers. Desertion was treated with the utmost rigor of military law, with the public execution of four out of five recaptured absconders serving as a stern reminder to the troops that the failures and deficiencies of the past were not going to be tolerated in the future. Nor was the vital aspect of health ignored. Remembering the winter horrors of sickness that had decimated the ranks at Sackets Harbor (when proper procedures for the disposal of sewage and waste were ignored), strict orders were issued for the establishment and maintenance of proper sanitary arrangements and regular cleaning of the living areas and camp kitchens — precautions that quickly reduced the incidents of sickness to a minimum. In addition, the troops were ordered to undertake the previously unheard of practice of regular bathing three times a week! Moreover, to ensure compliance with this directive, officers were directed to march their companies down to the lake and “cause the men to wash themselves from head to foot, but not to remain immersed in the water more than five minutes….”[1]

Over the following weeks, the men of the Left Division gradually became an efficient military force. Even their formidable commander expressed his approval of their state of training when he wrote, “I have a handsome little army…. The men are healthy, sober, cheerful and docile. The field officers highly respectable, and many of the platoon officers are decent and emulous of improvement. If, of such material, I do not make the best army now in service, by the 1st of June, I will agree to be dismissed the service…”[2]

As the summer campaign season approached, additional regiments of regulars and militia arrived at Buffalo and were immediately subjected to the regimen of drills and manoeuvres in an attempt to bring them up to the standard being set by the original units of the corps.

We encamped on the left of the regulars in a piece of bushy ground, which was soon cleared off, making it a beautiful spot, with a fine spring close by the encampment. Regulations new to us and very strict were now adopted. We rose at 4 o’clock (reveille beat) and answered to our names. We had fifteen minutes to prepare for drill, which generally lasted one hour. Breakfast being over, the regiment was formed, roll again called, guards detailed, and the regiment dismissed for a short time.

The Sergeant’s drill came next, which generally lasted till eleven o’clock. At two the Adjutant-General drilled, which was then dismissed till nine, when the roll was again called and we retired to rest. The time passed away in this manner, constant exercise, wholesome provisions, and strict discipline soon made our regiment have another appearance.[3]

— Alexander Mc Mullen,

Colonel Fenton’s Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers

Unfortunately, some elements of these militia reinforcements did not meet the exacting standards of Brigadier General Scott, and his opinions on these troops and their leadership became a significant source of friction within the American command structure in the ensuing campaign.

The [regular] troops here are getting into a state of very tolerable organization … & discipline. No exertions of mine have or shall be spared to perfect them in those essentials…. Col. Campbell & Com. Sinclair made a visit to Long Point a few days since; burned the mills & some other houses and have returned to Erie. No resistance of consequence was experienced. I now look for the fleet with the troops on board every hour. Col. Fenton & his militia are already in march for this place. I am sorry for this circumstance, for I had rather be without that species of force than have the whole population of New York and Pennsylvania at my heels. I now give it as my opinion that we shall be disgraced if we admit a militia force either into our camp or order of battle. By the way, I suspect Gov. Tomkins & P.B. Porter esqr. of a stratagem against myself & the other Brigadiers of this army. He [Porter] is very ingeniously styled General in all official communications between them; but whether he has the commission of Lieut. General or Maj. General in his pocket, is cautiously concealed. I wish not to conceal my determination never to submit to the orders of a militia-man whilst I hold a commission in the line. I hold myself prepared to leave the service on this point.[4]

— General Scott to General Brown, May 23, 1814

As mentioned in Scott’s letter, this new and largest of the American incursions into Upper Canada had taken place on May 14–16, when some 800 troops were transported by vessels from Erie, Pennsylvania, to the area around Long Point and Port Dover[*5] under Colonel John Campbell (Nineteenth Regiment). According to the local senior Canadian militia commander, Colonel Talbot:

… unfortunately, from the dispersed state of the Militia, it was impossible to assemble the Militia in sufficient time to oppose the landing of the Enemy…. The weather was so extremely foggy that the approach of the American vessels was not perceived more than an hour before they landed. I found it therefore necessary to retire as far as Sovereigns Mills, as did Lieu’t Burton with the detachment of the 19th Light Dragoons, for the purpose of affording time for the Militia to collect.[6]

— Colonel Talbot to Drummond, May 16, 1814

ESTIMATE OF THE AMERICAN FORCE, RAID ON LONG POINT AREA, MAY 14–16, 1814

Nineteenth Regiment (Captain Chunn), 1 company

Twenty-Second Regiment (Major Martin), amalgamated companies

Twenty-Fourth and Twenty-Seventh Regiment (Lieutenant Allison), amalgamated companies

Twenty-Sixth Regiment (Lieutenant McDonald), 1 company

Colonel Fenton’s Pennsylvania Militia (Major Galloway and Major Wood), detachment

Canadian Volunteers (Abraham Markle), detachment

U.S. Sailors and Marines (Commander Unknown), artillery detachment, est. 50 men with three field pieces

Estimated total: approximately 800 all ranks

During the next two days, the communities at Patterson’s Creek (Lynn River), Charlotteville (Turkey Point), Dover Mills, Finch’s Mills, Long Point, and Port Dover all suffered from American attacks that saw the destruction of their public buildings, grain mills, distilleries, private homes, and barns at the hands of the invaders. Even the crops in the fields and cattle were deliberately destroyed in order to reduce the ability of the region to support the British Army in the field.

Without the support of the regular forces Drummond had previously planned to establish in this area to oppose exactly this kind of threat. The hastily assembled Canadian militia detachments and Light Dragoons could put up only a token show of opposition against the substantially larger landing force, backed by the guns of their ships. Nor could they keep up, as the Americans used their boats as rapid transports between their several landing points, whereas the infantry component of the defenders had to make a series of forced marches in their attempts to defend the various locations. Had the Americans now pressed home their advantage, or been properly supported by additional reinforcements as Brown had originally intended, there would have been nothing to stop them from marching overland, taking Burlington Heights, and cutting off the entire British force on the Niagara frontier. Instead, the Americans eventually retired from the region, leaving behind an area of scorched earth and smouldering buildings.

Less than a week later another American incursion, this time from the Detroit frontier, took place against Port Talbot. Composed of about thirty riflemen and guided by the renegade Andrew Westbrook, the American raiders entered the village with the intention of capturing Colonel Talbot and as many other militia officers as possible, as well as acquiring plunder and supplies. In the event, the colonel was at Long Point, dealing with the aftermath of Campbell’s raid. However, the Americans did capture several other Canadian militia officers and men. Before they could retire with their prisoners and loot, however, it was learned that one of their prisoners had escaped. Alarmed that the escapee could guide any nearby Canadian militias or British regulars directly to their location or cut off their retreat, the Americans made a hasty departure with their loot and abandoned their prisoners — after forcing them to swear their paroles.

These two incursions so alarmed Major General Riall that despite having already abandoned the entire region of the upper Thames Valley, he now went so far as to request permission of Lieutenant General Drummond to withdraw most of his troops from their forward positions along the Niagara River and concentrate them at Burlington Heights, where, he argued, they could be used to counter any future American advance from the south, west, or east. Turning down this request, Lieutenant General Drummond ordered Riall to maintain his main force on the Niagara and strengthen his positions along the Grand River boundary as much as possible. By these measures, Drummond not only hoped to slow any possible American attack until reinforcements could be concentrated from their scattered positions elsewhere or brought up from York and Kingston, but was also determined to protect those inhabitants still attempting to scratch out a living and grow the crops that could feed

his troops.

In addition, the fact that both raids had included renegade settlers persuaded the authorities to take a much harder line with those who were considered as turncoats and traitors and who came under the hand of the Crown. As a result, a group of nineteen Upper Canada residents who had gone over to the American side and then been captured while participating in earlier American raids, were arraigned on charges of high treason. A further fifty were charged in absentia. The trials for those in custody began in June at Ancaster and lasted for two weeks under the supervision of Chief Justice Thomas Scott, Senior Puisne Justice William Powell, and Junior Puisne Justice William Campbell. Of those placed on trial, one pled guilty and four were acquitted. The remaining fourteen were found guilty and deemed subject to the penalty enacted on all those convicted of treason — death. In fact, only eight of this group were executed on July 8, 1814, while the remainder were reprieved and received varying terms of imprisonment. Three subsequently died of “jail fever,” three were later pardoned, and one was reportedly able to escape his custody in the Kingston jail and succeeded in crossing into the United States.

Finally, these raids had another wider and long-term repercussion, as they resulted in yet another round of accusatory letters being dispatched; first from Major General Riall to Colonel Campbell on June 9th “to request from you an explicit declaration whether these acts were authorized by the Government of the United States.”[7] To which Campbell proudly replied on June 16th, “I commanded the detachment … what was done at that place and its vicinity proceeded from my orders. The whole business was planned by myself and executed upon my own responsibility.”[8] Riall also received testimonies from the victims of the raid that Campbell had repeatedly claimed the raid was a direct reprisal for the British burning of Buffalo the previous December. (For details see The Flames of War.)

This then brought in both Lieutenant General Drummond, who made an official complaint to Major General Brown at Buffalo, and Sir George Prevost, who made similar protestations to the American government about the depredations and wanton destruction committed on private property by Colonel Campbell’s troops. In a remarkably short period of time, a court of inquiry was held at Buffalo under the superintendence of Brigadier General Winfield Scott, Major Thomas Jesup, and Major Eleazar Wood, who equally as rapidly exonerated Campbell of all imputation of wrongdoing in the burning of the mills, distilleries, sawmills, and associated structures (as in their judgement they were viable military targets, being used by the military to supply their needs). As to the burning of the private dwellings, Campbell was deemed to have been technically in error in those cases, but that the actions were understandable as a justified and honourable reaction to the prior unjustified and criminal British burning of civilian settlements at Buffalo. In a similar fashion, the American administration brushed off Prevost’s complaint. This American aggression and the subsequent arrogant dismissal proved to be the final straw as far as Prevost was concerned and he subsequently dispatched highly incensed reports to both Whitehall and Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane at Halifax, then commanding the British raiding forces operating along the American northeast coast. In this latter communiqué, Prevost indicated that, as far as he was concerned, if the Americans wanted to play a game of tit-for-tat in reprisals and burnings, Cochrane was free to show them what such a policy would result in — a reality that Stonington (CT), the settlements along the Chesapeake Bay, and ultimately Washington, D.C., felt during the forthcoming months.