CHAPTER 9

The Battle of Chippawa

For Major General Riall, the American landing at Fort Erie triggered a preplanned concentration of his troops from as far away as York and Burlington into the Niagara frontier, while the units at Queenston and Fort George bolstered the Chippawa River defence line. Confident of the strength of this defensive position, Riall was well pleased with the delaying tactics of Lieutenant Colonel Pearson, while the support of the Native Natives gave him an additional light force to harass the enemy flanks. By the morning of July 5, further units of regular and militia infantry, artillery and cavalry had arrived to bolster his line.[*1] His choice now was whether to remain on the defensive or to attack.

Because he had developed a low opinion of the quality of the American troops after their dismal showing at Buffalo the previous December (for details see The Flames of War), and having made his own reconnaissance of the American positions that persuaded him that Fort Erie was detaining a sizeable part of the American force at the far end of the Niagara River, Riall believed there was an opportunity to strike at the enemy while they were still separated. He therefore decided to advance and attack the American encampment. What he didn’t know was that as well as Ripley’s Second Brigade, Porter’s Third Brigade had now completed its crossing of the Niagara River and was advancing north to create an American force that far outnumbered Riall’s own.[*2]

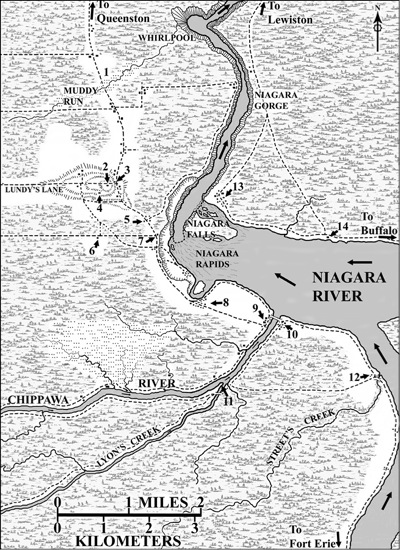

LOCATIONS AROUND THE GREAT FALLS OF NIAGARA JULY, 1814

1. Cook’s bog or “muddy run”

2. The Lundy’s Lane church on the hilltop

3. Johnson’s Tavern at the Lundy’s Lane/Portage Road crossroad

4. Buchner farmstead

5. Forsyth’s Tavern

6. Haggai Skinner’s farmstead

7. Mrs. Wilson’s tavern

8. Bridgewater Mills

9. British fortifications at the Chippawa River

10. Chippawa Village

11. Weishoun’s Point

12. Ussher’s farmstead

BRITISH FORCES, BATTLE OF CHIPPAWA,

JULY 5, 1814

(Major General Phineas Riall)

British Regulars

1st (Royal Scots) Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel John Gordon), 500 rank and file

8th (King’s) Regiment (Major Thomas Evans), 480 rank and file

100th Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel George Hay, Marquis of Tweedale), 450 rank and file

Canadian Militia

2nd Lincoln Militia Regiment (Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Dickson), 200 rank and file

Artillery (Captain James Maconochie)

Lieutenant Sheppard’s Battery (3 x 6-pounder guns)

Lieutenant Armstrong’s Battery (2 x 24-pounder guns)

Lieutenant Jack’s Battery (1 x 5 ½ inch Howitzer)

Total: 70 crew

Cavalry (Major Robert Lisle)

19th Light Dragoons, 70 troopers

British Native Allies (Captain Norton)

300–350 Warriors

AMERICAN FORCES, BATTLE OF CHIPPAWA,

JULY 5, 1814

(Major General Jacob Brown)

First Brigade (Brigadier General Winfield Scott)

Ninth/Twenty-Second Regiment (Major Henry Leavenworth), 700 rank and file

Eleventh Regiment (Major John McNeil), 500 rank and file

Twenty-Fifth Regiment (Major Thomas Jesup), 360 rank and file

Second Brigade (Brigadier General Eleazar Ripley)

Nineteenth/Twenty-First Regiment (Major Joseph Grafton) 725 rank and file (80, Ropes’ Coy)

Twenty-Third Regiment (Major Daniel McFarland), 450 rank and file

Third Brigade (Brigadier General Peter B. Porter)

Fifth Pennsylvania Militia Regiment (Major James Wood), 540 rank and file (200)

American Native Allies (Lieutenant Colonel Erastus Granger), 400 Warriors (300)

Artillery (Major Jacob Hindman)

Captain Biddle’s Battery (3 x 12-pounder guns, 80 crew) (25)

Captain Richie’s Battery (3 x 6-pounder guns and one 5 ½ inch howitzer, 96 crew) (96)

Captain Towson’s Battery (2 x 6-pounder guns and one 5 ½ inch howitzer, 89 crew) (89)

Captain William’s Battery (3 x 18-pounder guns, 62 crew)

Cavalry (Captain Samuel D. Harris)

Light Dragoons (1 troop)

(N.B. Although these figures represent what was at the field during the day, only portions of the Second and Third brigades saw action. The bracketed figures are an estimate of the real numbers of American rank and file that fought on the day and, as in the case of the British figures, do not include non-commissioned officers, officers, command staff, and supporting forces.)

Prior to this fateful decision, Riall had sent out his Native allied troops during the night with orders to skirt the American encampment and scout out their dispositions, but not engage the enemy. While Norton’s warriors obeyed this directive, some of those refusing to obey Norton’s leadership found the American sentries too much of a tempting target and began firing, inevitably drawing fire in return. Initially ignoring the harassing fire, Major General Brown’s patience had worn thin by noon and he chose to use Porter’s approaching column of militia and American Native allies to clear the woods of this annoyance. According to General Porter’s later account, General Brown notified him that:

… about three fourths of a mile distance between the river and an almost impenetrable forest was infested with a band of Indians & militia conversant with its haunts & sent from the British camp to annoy and assail our pickets; that he had that morning been under the necessity of making an example of a valuable officer [Captain Treat (Twenty-First Regiment)] for suffering his guard to be driven in [and leaving a wounded man on the field] & the army thus exposed to the direct fire of these troublesome visitants. That it was absolutely necessary for their quiet & safety of the camp that these intruders should be dispersed; and as regular troops were ill qualified for such service … that he [Porter] should with his Corps of warriors, aided if necessary by the volunteers, scour the adjoining woods and drive the enemy across the Chippawa, handling them in such a manner as would prevent a renewal of this kind of warfare — assuring him in the most confident terms that there was not and would not be in the course of that day, a single regular British soldier on the south side of the Chippawa.[3]

The Opening Moves, 5:00 a.m–3:30 p.m.

Coincidentally, this was just about the time Major General Riall ordered his troops to repair the Chippawa bridge and prepare for an attack. Because a wide band of trees blocked the line of sight between the open ground of the Chippawa riverbank and the fields in front of the American camp, neither general was fully aware of the movements of their enemy. Consequently, when they both decided to advance their light troops through the woods to the west of the American camp, a collision of forces became inevitable.

Having just marched from Fort Erie under hot and humid conditions, Porter’s men were tired. Nevertheless, more than 200 of the Pennsylvania Militia volunteered to participate in the attack. Giving these men time to take a brief rest and eat, Porter also detailed his 300 Native warriors to join in the advance. Preparing for battle, Porter’s warriors applied war paint and tied strips of white cloth around their heads to distinguish them from the warriors fighting for the British.

Around 3:30 p.m. both forces began to move out from their respective encampments. From the British positions, Riall led his force across the repaired bridge. Leading the advance was a strong detachment, composed of the light companies of the 1st (Royal Scots), 8th (King’s), 100th, 2nd Lincoln Militia regiments, and a body of Native warriors (who had refused to follow Norton). After crossing the river, this force was detached to the right, where it halted and fronted the woods, anchoring the British line of advance. Meanwhile, the main body of troops (the 19th Light Dragoons, the remaining companies of the 100th regiment, the artillery batteries of Lieutenant Armstrong and Lieutenant Sheppard, the remaining companies of the 1st [Royal Scots] regiment, and the remaining companies of the 8th [King’s] regiment), followed the curve of the track that paralleled the Niagara River, marching toward the American camp. In addition, a separate body of Native allies under Norton crossed over and advanced further to the right (west), intending to outflank the American pickets and come at the American camp from the rear.

For their own part, Porter’s Native warriors, Pennsylvanian volunteers, and a detachment from the regulars under Ripley’s Aide (Lieutenant McDonald) advanced up to the wood line, with the Native warriors passing into the woods in single file, while the militia and regulars remained in the open ground, thus creating a cordon of men that stretched for almost three-quarters of a mile (one kilometer). Upon command, this line then halted, faced to the right (north), and began to cautiously sweep forward through the dense bush toward Street’s Creek and the sounds of the sporadic firing of the enemy upon the American camp. Within moments, the Americans began to encounter small parties of British allied Natives. Outflanked and outnumbered, many wisely took to their heels and attempted to outrun the advancing wave of Americans, while others, finding themselves cut off, fought until they were overwhelmed, with no quarter being given on either side. Within a short time, the American advance had degenerated into clusters of men engaged in a running battle, with visibility restricted to a few yards and hand-to-hand combat being the rule. Outside the woods, Major General Brown rode north and was able to follow the advance of Porter’s troops by listening to the sporadic sounds of musket fire coming from the treeline. By the time he reached Brigadier General Scott’s camp, things seemed to be going well, as the harassing fire on the sentries had ceased and was receding further north toward the British position at the Chippawa. Having promised Porter the tactical support of Winfield Scott’s troops should it be necessary, and finding Scott was asleep in his tent, Brown deduced this would not be required and continued forward to the advanced picket lines on the far side of Street’s Creek. Suddenly, the sounds of firing from the woods changed dramatically, for instead of the staccato and overlapping fire of individual muskets, the noise deepened into the rumbling barks that could only be produced by musket volleys from disciplined troops, formed in line-of-battle.

This sonic signal, indicating that the fighting had entered a new and more serious phase, was the result of a series of events that had taken place unseen by Brown, during the previous half hour. Within the woods the rout of the British Natives had led the American Natives forward at such an impetuous pace they were unprepared for what lay ahead as they approached the northern limit of the woods. For his part, Lieutenant Colonel Pearson, commanding the British light troops, militia, and part of the Native force, noted the approaching noises of firing from the woods to his front and advanced the 2nd Lincoln Militia Regiment, supported by a force of one hundred western Native warriors, into the woods to counter the obvious American advance. As a result, the two forces met head-on in the dense woods and a firefight ensued, in which the American Native allies fared worse and began to retire in as much haste as they had previously advanced. Moving forward in their turn, the Lincolns and British Native allies came up against more and more American warriors who were by then rallying alongside the position of the American Third Brigade militiamen and the reserve of regulars. The two forces began to fire into each other at extremely close range, inflicting casualties on both sides. After some fifteen minutes of intense fighting, the Lincolns and Natives pulled back once more and emerged from the woods, hotly pursued by the entire body of Americans, who were intent on catching their enemy — that is, until they suddenly burst out from the forest into the open ground and realized that instead of chasing militia and Natives they were facing a solid wall of redcoats in line.

The British regulars and regrouped militiamen opened up on the surprised Americans with their disciplined volleys (thus alerting Brown at the American camp that a new element had been added to the day’s conflict) before advancing with the bayonet into the woods, sweeping all before them. This time there was no hope of Porter rallying his forces and the American general joined his men in retiring back toward the American camp with all dispatch.

Meanwhile, Major General Riall had marched his main force of regulars along the dusty riverside road and past a belt of trees that almost reached to the riverbank, before ordering the 1st (Royal Scots) and 8th (King’s) regiments to move off to the right into more open ground. As a result, the British force now advanced in three separate columns, placed in echelon. Opposite him, Major General Brown reacted to the sounds of volley fire and the approaching dust clouds by dispatching his adjutant general, Colonel Gardner, to order the First Brigade forward and then bring up the Second Brigade in support. Reaching Winfield Scott’s tent, Gardner found the general awake and in a good mood after his nap, while his troops were “kitting up” and forming their companies. To Gardner’s concern, however, he learned that, far from preparing to go into battle, the men of the First Brigade were dressing to practise drill manoeuvres according to Scott’s orders for the day. Attempting to alert the general to the imminent danger, Colonel Gardner was dismissed by Scott as an alarmist. Nevertheless, Scott obeyed his new orders and led his brigade toward Street’s Creek, where he met up with Major General Brown, who was returning in haste to form his army, having already seen the columns of redcoats emerging from the woods to the north. Even now, Scott discounted Brown’s admonition that he was going into battle and retorted with his positive conviction that “he would march and drill his Brigade but that he did not believe he should find 300 of the enemy….”[4] He then self-confidently marched his brigade past a wall of bushes and trees lining the creek and reached the cleared ground alongside the bridge. At this moment, Scott’s arrogant illusions were quickly swept away as the advancing British troops came into his view and Armstrong’s artillery battery opened fire upon his brigade.

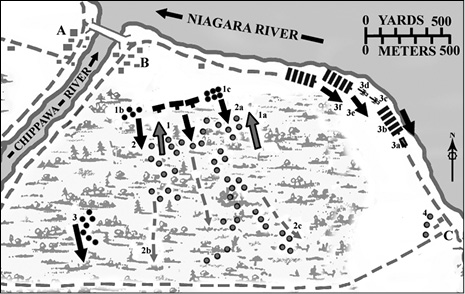

The Fight in the Forest, 3:30–3:50 p.m.

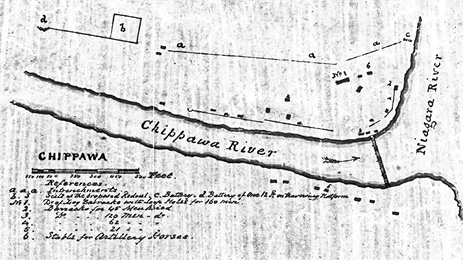

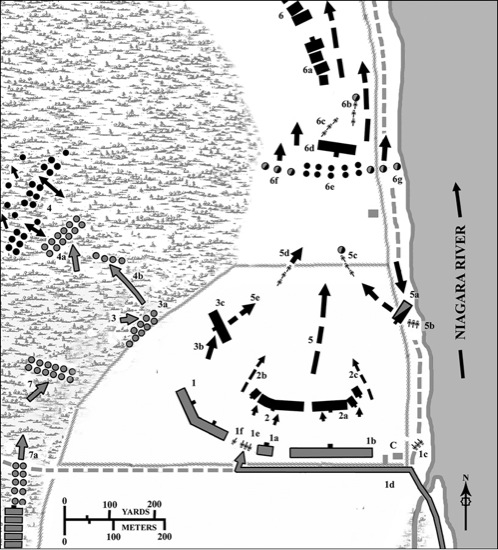

A Chippawa fortifications and main British lines

B Chippawa Village

C Ussher’s Farmstead, location of U.S. advance post guarding the Street’s Creek Bridge

1. British Native allies (1–1a), faced with the advance of the strong force of American militia and Native allies (1b–1c), retreat toward Chippawa village (B).

2. The main British column (2–2e) advances along the riverbank road, as the light troops (2f) move up to the wood line and form a line (2g–2h) in response to the approaching sounds of firing within the forest.

3. Detachments of the Canadian militia and British Native allies (3, 3a) advance to support the retreating British Native allies (1, 1a) and force the leading elements of the advancing Americans (1b, 1c) to retreat (3b–3c).

4. Accumulating reinforcements from their own forces, the American’s rally (4–4a) and counterattack the advancing British (4b–4c), forcing the British to retreat (4d–4e) toward their supporting line (2g–2h).

5. Norton’s warriors (5) continue their flanking movement through the forest, while at Ussher’s farmstead (C) near the riverbank, Captain Ropes’ company of the Twenty-First Regiment (5a) is alerted to possible British movements by the clouds of dust approaching from Chippawa.

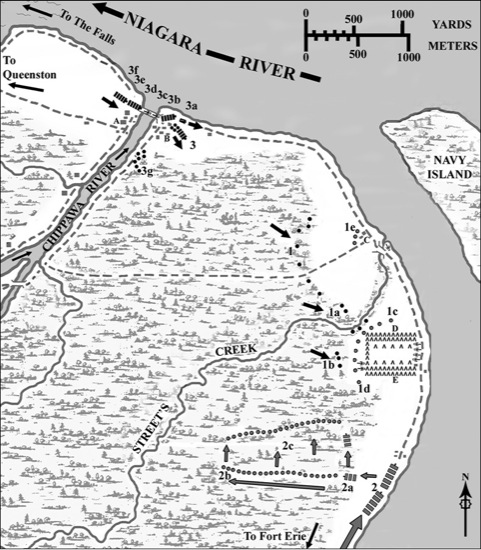

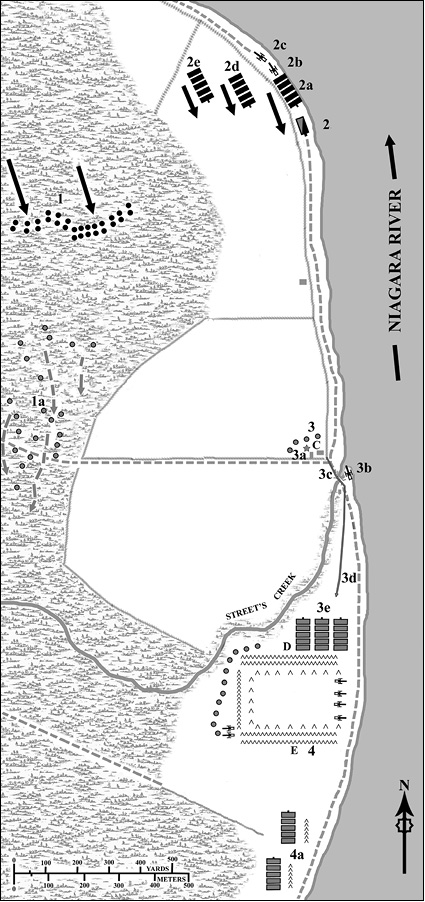

The American Third Brigade is Routed, Approximately 4:00 p.m.

A Chippawa fortifications and main British lines

B Chippawa Village

C Ussher’s Farmstead, location of U.S. advance post guarding the Street’s Creek Bridge

1. Porter’s troops (1–1a) pursue the retreating British detachments, only to break out of the forest to find themselves facing a British line (1b–1c), which opens fire with volleys.

2. After a number of volleys, the entire British Light force advances (2, 2a), routing the disrupted American force (2b, 2c).

3. On the British right flank, Norton’s warriors (3) slowly advance; on the left, Major General Riall’s main column revises its disposition into a staggered three-column formation. Left column: 19th Light Dragoons (3a), 100th Regiment (3b), Armstrong’s artillery battery (3c), and Sheppard’s artillery battery (3d). Centre column: 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment (3e). Right/reserve column: 8th (King’s) Regiment (3f).

4. At Ussher’s farmstead (C) Captain Ropes’ Twenty-First Regiment (4) dispatch reports of the possible threat of attack to Major General Brown at the encampment.

Leading the British force of some 1,200 rank and file onto the field, Major General Riall ordered his columns to deploy into line across the open ground. Nearest the Niagara River and anchoring the British left flank was the artillery of Lieutenant Armstrong with two huge 24-pounder guns (usually reserved for garrison or static earthwork positions) and a five-and-a-half-inch howitzer. Next came the 100th Regiment, which would form the left flank of the infantry line, but due to some unspecified error of command, or perhaps due to the lack of room to deploy from right to left in proper company sequence, the 100th found itself deploying in a “clubbed” company formation. As such, the normal alignment placing the senior “Grenadier” company on the right of its regimental line was reversed to the far left, causing a small but critical temporary disruption in the smooth establishment of the British battle line. Further to the right, the 1st (Royal Scots) had more ground to manoeuvre and consequently deployed in its proper company order. Ideally the 8th (King’s) Regiment would then have swung into line, solidifying the right flank, but unfortunately there was not enough clear ground to allow this manoeuvre and the regiment was forced to deploy slightly to the right rear of the Royal Scots. Within the resulting gap on the right of the Royals, Lieutenant Sheppard of the Royal Artillery instead placed his three 6-pounder cannons. Finally the small detachment of 19th Light Dragoons took post to the rear of Armstrong’s guns, completing the initial British formation.

Prelude to a Battle, 4:00 –4:15 p.m.

C Ussher’s farmstead, location of U.S. advance post guarding the Street’s Creek Bridge

D Brigadier General Scott’s (First Brigade) encampment

E Brigadier General Ripley’s (Second Brigade) encampment

1. The British light troops, Canadian militias, and British Native allies (1) press forward through the forest in pursuit of the routed American Third Brigade troops and American Native allies (1a).

2. Major General Riall’s main series of columns, composed of the 19th Light Dragoons (2), the 100th Regiment (2a), Armstrong’s artillery battery (2b), and Sheppard’s artillery battery (2c). The 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment (2d) and the 8th (King’s) Regiment (2e) approach the open fields fronting the American position.

3. At the Ussher’s farmstead (C), the American advance position (Captain Ropes’ company, Twenty-First Regiment) (3) is joined by Major General Brown and his senior staff (3a). Hearing the sounds of volley fire from the forest and seeing the approaching dust cloud on the riverbank road, Brown decides to bring his army to a higher level of readiness for action, starting with the nearby Towson’s artillery (3b). Major General Brown also sends his adjutant, Colonel Gardner (3c) riding back (3d) toward Brigadier General Scott’s encampment (D) to bring up the First Brigade and then alert Brigadier General Ripley’s Second Brigade (E). Upon arriving at Scott’s encampment, Gardner finds the First Brigade already mustered, but not for action — for a drill parade! (3e)

4. At Brigadier General Ripley’s encampment (E), the general is still unaware of the heightened alert and his Brigade remains in camp (4). To the south, the remaining uncommitted elements of Brigadier General Porter’s Brigade (4a) begin the establishment of their own encampment

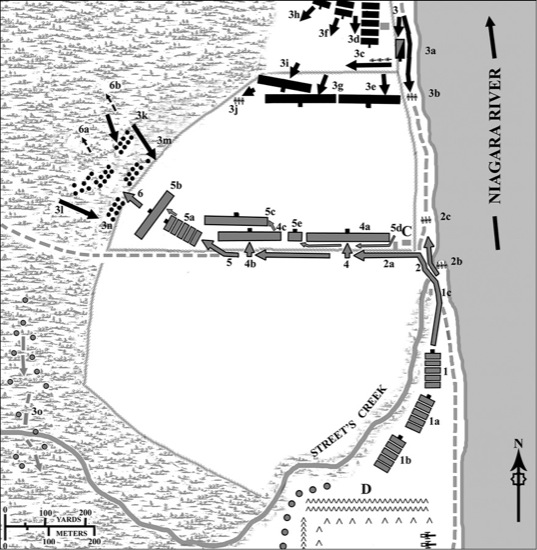

Initial Deployment and Engagement, 4:15–4:30

C Ussher’s farmstead, location of U.S. advance post guarding the Street’s Creek Bridge

D Brigadier General Scott’s (First Brigade) encampment

1. Brigadier General Scott marches his First Brigade: Ninth/Twenty-Second Regiment (1), Eleventh Regiment (1a), and Twenty-Fifth Regiment (1b), along the wooded bank of Street’s Creek and is therefore unable to see the approaching British force. At the Street’s Creek Bridge (1c) Scott’s Brigade comes under fire from Lieutenant Armstrong’s battery (two 24-pounders, one 5½-inch mortar) (3b) located on the riverbank road. This fire is answered by Towson’s artillery battery (two 6-pounders, one 5½-inch mortar) (2b).

2. Crossing the Street’s Creek Bridge (2) Scott’s Brigade turns left (2a) into the lane running behind the Ussher’s farmstead (C), while Towson’s artillery battery relocates to a position on the riverbank road and slightly forward of the Ussher’s farm (2b, 2c). From here it recommences counter-battery fire on the British artillery.

3. Simultaneous to 1 and 2, the British deploy into line-of-battle. On the riverbank road, the 19th Light Dragoons (3) halt. The artillery advances (3a), with Armstrong’s battery unlimbering on the riverbank road (3b), while Sheppard’s battery moves toward the British right flank (3c). The 100th Regiment (3d) advances and forms the left of the infantry line (3e). The 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment (3f) deploys in the centre (3g). The 8th (King’s) Regiment (3h) also advances, but due to the lack of open ground on the right flank is forced to deploy to the rear (3i). Sheppard’s artillery battery (three 6-pounders) (3j) deploys and opens fire as the right flank of the main British line. Within the forest, the British light troops (3k, 3l) advance to the edge of the wood line (3m, 3n) threatening the American left flank, but cease pursuing Brigadier General Porter’s troops (3o).

4. The Ninth/Twenty-Second Regiment (4) wheels right, breaches the fence to enter the field, and deploys into line (4a). Similarly, the Eleventh Regiment (4b) deploys into line (4c).

5. Seeing the British light threat (3m, 3n), Scott orders the Twenty-Fifth Regiment (5) to advance and disperse the enemy. During its advance (5a), the Twenty-Fifth comes under heavy fire from the British troops in the forest, as well as Sheppard’s artillery (3j), but still forms line (5b) and opens fire. Scott also moves the Eleventh Regiment forward and to the left (5c) to outflank the British line. The resulting gap is filled by relocating Ropes’ company from Ussher’s farmstead (C) to fill the gap (5d, 5e).

6. The Twenty-Fifth line (6) advances to the wood line, delivers three volleys, and presses into the forest. In response, the British Light troops begin to retreat (6a, 6b).

In opposition to this, the somewhat chagrined Winfield Scott pressed forward his First Brigade across the Street’s Creek bridge while under fire. Off to his right, Captain Towson of the U.S. Artillery, having already opened fire on Armstrong’s British guns, now ceased fire, limbered his guns (two 6-pounders and a five-and-a-half-inch howitzer) and also advanced across the bridge, before establishing his battery alongside the Ussher farmstead and recommencing counter-battery fire on Armstrong’s position. Wheeling left from the bridge, Scott marched his column along a lane that ran west from the river road behind the Ussher Farm. He then swung the formation to the right and moved into the open field in front and began deploying his own troops in the classic line formation. Anchored on the right by Towson’s guns, the American line now consisted of the combined Ninth/Twenty-Second Regiment on the right, the Eleventh Regiment in the centre, while the Twenty-Fifth Regiment continued to move to the left in column. Having seen considerable battlefield service and having practised long and hard over the previous months, the Ninth/Twenty-Second and Eleventh reacted to the current situation with calm efficiency and discipline. Watching from the other side of the field, Major General Riall realized that despite the grey coats worn by these troops (which had previously misled him into believing them to be relatively undisciplined militia troops, such as those he had routed at Buffalo only six months before) he was, in fact, facing regularly trained and fully disciplined regiments, to which he is reputed to have stated, “Why these are regulars by God!”[5]

At this point, elements of Pearson’s red-coated light troops and groups of Native Warriors began to appear along the wood line, in front of the American left. In response, Scott revised his formation even as it was forming and, instead of having the Twenty-Fifth turn and form line, he directed them to move across the open ground to deal with this threat. He also moved the Eleventh further to the left, leaving a gap between it and the combined unit of the Ninth/Twenty-Second. Under normal circumstances this would create a dangerous weak spot in a battle line, but this was partially filled as the advance picket from the Twenty-First Infantry Regiment (Captain Ropes), located at Ussher’s Farm, was moved across into the opening.

As the two infantry formations were still beyond effective musket range, the only firing at this point was between the artillery batteries on the flanks. Nearest the river, Towson’s battery and Armstrong’s guns inflicted casualties on each other in an attempt to gain mastery of that flank, each losing the use of a gun in the process. Across the field, Sheppard’s guns had a clear target in the form of the Twenty-Fifth advancing across the open ground toward the woods. Opening up with roundshot at a range of around 400 yards (366 meters), his guns quickly inflicted a number of casualties as the solid spheres bowled through the densely packed column.

After seeing the artillery doing effective duty on the enemy, Major General Riall decided the time was right to close on the enemy with his line. The formation to his front had proved it was fully capable of deploying and forming under fire and was no mere militia that would run at the first sign of fighting, but its numbers corresponded with that of his intelligence reports as roughly equal to his own. Confident in the superiority of his own troops in a toe-to-toe firefight, he ordered the 100th and 1st (Royal Scots) regiments forward, while bringing the 8th (King’s) Regiment up at an angle to counter the movement of the Twenty-Fifth Regiment.

Inevitably, this forward movement masked (blocked the firing of) both of the British gun batteries, forcing Armstrong (on the left) to cease fire and limber up his guns prior to moving forward to a new position where he would have a clear line of fire. However, Sheppard’s battery was unable to move up and became completely blocked on the British right, allowing the Americans a momentary respite before the lines closed to effective killing range. Viewing the advance, Winfield Scott realized that the angled advance of the 8th (King’s) line was creating a gap between its left flank and the right flank of the 1st (Royal Scots) and that his own formation extended past the foreshortened main British line. He therefore ordered the Eleventh to swing its left flank forward so that it could commence firing obliquely into the exposed Royal Scots flank. Scott then rode across the entire American line to Towson’s battery and redirected its fire onto the advancing British line in a similar oblique fashion.

As the lines closed to less than one hundred yards (91 meters) apart, the first American volleys tore into the redcoat formation, bringing it to a momentary halt. True to its discipline, however, the line absorbed the punishment, closed ranks, and continued its march forward, only to receive further volleys of musketfire and point-blank cannonfire from Towson’s guns. Brought to a complete halt, the British line returned the compliment of musketry on the Americans, likewise creating gaps that were quickly filled as the companies closed on their colours. Volley followed volley from both lines and the dogged determination of each force not to budge or waver only served to increase the toll of casualties, especially amongst the 100th Regiment, who were directly in front of Towson’s guns and had entire segments of their line scythed away with each blast from the American battery. Nor were the 1st (Royal Scots) in a much better position on the right, as the American Eleventh Regiment used their advantageous flanking position to pour in their deadly volleys.

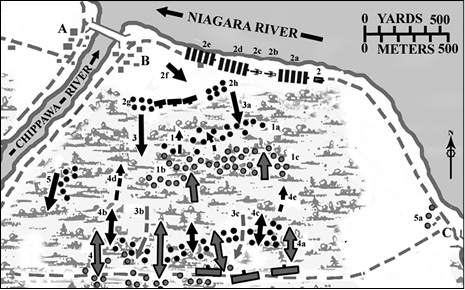

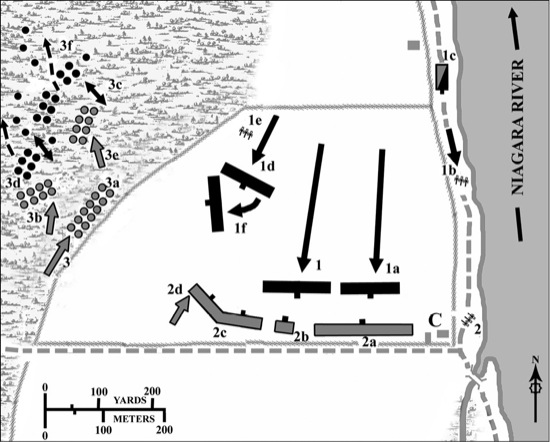

Close Quarter Slaughter, 4:30–5:15 p.m.

C. Ussher’s farmstead

1. Determined to close with the enemy, Major General Riall orders the 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment (1) and 100th Regiment (1a) to advance in line directly toward the centre of the American line. In support, Armstrong’s battery moves (1b) down the riverbank road, covered by the 19th Light Dragoons (1c). The 8th (King’s) Regiment (1d) advances to the right, thereby “masking” (blocking the firing of) Sheppard’s battery (1e) and preventing it from providing supporting fire. As it advances, the 8th (Kings) is threatened by the Twenty-Fifth troops at the wood line (3a) and forced to wheel right (1f), preventing it from completing the formation of the main British firing line.

2. Towson’s artillery (2) switches its fire from Armstrong’s guns (1b) and targets the approaching left flank of the 100th Regiment (1a). The Ninth/Twenty-Second Regiment (2a) and Ropes Company, Twenty-First Regiment (2b) and Eleventh Regiment (2c) also open fire as the British line comes within range. However, due to the detachment of the 8th (Kings) Regiment (1f), the British line is foreshortened. In response, the Eleventh Regiment wheels forward its left wing (2d), enfilading the British line.

3. Simultaneous to 1 and 2, the Twenty-Fifth Regiment (3) advance along the fence line (3a) threatening the flank of the 8th (King’s) Regiment (1f), while Captain Ketchum’s company (3b) is detached to pursue the retreating enemy, only to be counter-attacked by the regrouped British light troops (3c–3d). In response, Ketchum is forced to call for reinforcements (3e), which arrive and force the British to make a fighting retreat (3f).

During this same interval, on the American left flank, Jesup’s Twenty-Fifth Regiment completed its oblique movement across the field and approached the woods where the British light companies, militia, and Natives were massing. Ignoring the intermittent fire coming from the enemy to his front and the occasional shot from Sheppard’s guns, Jesup now formed his regiment into line and opened fire. After a succession of volleys he then advanced in line, halting immediately outside of the wood line, fired three volleys into the disorganized British units and charged with the bayonet. Inevitably the Natives and militia melted back into the woods before this disciplined onslaught. Beside them, the regulars, heavily outnumbered and not properly reformed, were also forced to give ground, leaving the Americans in an advantageous position to move along the wood line and outflank the approaching 8th (King’s) Regiment. Detaching Captain Ketchum’s company to pursue the retreating British light troops, Jesup reformed his remaining force along the fence bordering the forest and opened fire into the flank of the 8th (King’s), which forced it to halt its advance and change its front to meet this new threat, thus increasing the gap between it and the remainder of the line. Additional volleys and a further advance along the flank by Jesup’s troops again compelled the 8th (King’s) to change position to face the American fire. Fortunately for the 8th (King’s), the British light troops regrouped in the woods and took on Ketchum’s company, compelling him to call for reinforcements from Jesup, effectively ending his movement around the British flank. Nevertheless, Jesup’s actions effectively prevented the 8th (King’s) from closing on the foreshortened British line, which would otherwise have terminated the deadly flanking fire of the Eleventh Regiment on the 1st (Royal Scots).

As a result, the main battle stalled and became a brutal matter of face-to-face pounding and attrition, as neither side could advance and neither was willing to retire. In this kind of competition, the advantage lay with the Americans, as Major General Riall had no reinforcements whatsoever, while Major General Brown now had the entire Second Brigade on the move toward Street’s Creek. However, instead of sending it along the direct and open road to the battlefield, which would have quickly brought this force into action at the crisis of the battle, Brown ordered Ripley to move off into the dense forest and push forward in a wide sweep to the west. By this he hoped to see Ripley’s troops surprise the British right flank or even succeed in getting behind, thus cutting the enemy off from retreating. He similarly directed Brigadier General Porter, who had succeeded in reforming part of his Third Brigade, including those that had not previously joined his initial attack, to make a parallel advance. However, both of these formations soon found themselves bogged down in the dense forest and unable to press forward with any speed, significantly delaying their commitment to the battle that was raging ahead.

The deciding factor in the battle came shortly afterward as fresh batteries of artillery (Richie’s company with two 6-pounders and a five-and-a-half-inch howitzer and Biddle’s company with a 12-pounder, under Lieutenant Hall) came up the riverbank road and moved into a firing position between the Eleventh and Ninth/Twenty-Second regiments. From this vantage point, the additional American guns opened up at point-blank range, tearing unfillable gaps in the already-depleted ranks of the British line. Under the cumulative slaughter of this remorseless and increasing assault, the British line began to recoil, beginning with the flanks, which had suffered most throughout the entire conflict. Seeing his force involuntarily beginning to lose ground, and perhaps noting an increasing number of American troops infiltrating along the western wood line, Major General Riall ordered a general withdrawal. Defeated, but not beaten, the 100th and 1st (Royal Scots) regiments disengaged and retired their reduced line out of musket range before forming a relatively orderly column and marching from the field, covered by the relatively intact formations of the 8th (King’s) and Light Dragoons.

Despite being elated by their success, the men of the First American Brigade had also suffered significant casualties and were in a partial state of disorder. They therefore did not immediately advance on the retreating British, but paused to regroup and reform their lines before marching forward, stepping over the distinct lines of British dead and wounded that marked the points at which the earlier British advance had been brought to a halt. Any attempt to turn the British retreat into a rout was foiled, however, by the strong rearguard of the 8th (King’s) Regiment and the 19th Light Dragoons, who denied the Americans the trophy of a disabled cannon in Armstrong’s battery by using their horses as draft animals to drag it from the field.

Reaching the Chippawa bridge, the British crossed unmolested and formed up behind their entrenchments, while the rearguard began demolishing the roadbed as the first American units appeared on the riverbank road. At the same time, groups of British Natives and militia, which had been fighting in the dense woods throughout the afternoon, began to emerge from the treeline and were forced to run for the bridge under fire from the American troops to save themselves from being cut off. Hoping to stall the American advance and give time for the last groups of Natives to cross, not to mention exact reprisals for their defeat, the British artillery batteries, located in the fieldworks on the north side of the Chippawa River, opened up on the Americans. This forced Winfield Scott’s column to halt their approach to the bridge and seek cover by lying down in their ranks to await reinforcements. Shortly thereafter, Brigadier General Porter arrived with his reformed units and joined Winfield Scott’s brigade in lying prone to avoid taking unnecessary casualties. From this vantage point they saw the last of the bridge roadbed removed and those of Norton’s Natives still on the south bank working their way across the upright pilings of the bridge.

About a half-hour later, Major General Brown arrived, accompanying Brigadier General Ripley’s brigade, and the combined group of commanders discussed the options for the army. Despite the fact that there was only an hour or two of daylight left, the American victory had elated the Americans to the point that everyone’s first judgement was to continue the attack and try to force a crossing of the Chippawa, disperse the enemy while he was still reeling from his bloody defeat, and end the campaign then and there. On the other hand, it soon became obvious that continuing the attack would be a problem, as night was approaching, giving the British the advantage. In addition, their earlier victory had only been gained at a substantial cost in killed and wounded within the First Brigade, the numbers of which were not yet assessed. Finally, the Chippawa bridge had been successfully dismantled by the British and any attempt to reach it and undertake repairs would expose the working parties to the full might of both the entrenched British gun batteries and the musket fire of every surviving enemy infantryman.

The British Position Crumbles and Disengagement

C. Ussher’s farmstead

1. The American line: Eleventh Regiment (1), Ropes’ Company, Twenty- First Regiment (1a), Ninth/Twenty-Second Regiment (1b), Towson’s artillery battery (1c) is supplemented by the arrival (1d) of artillery reinforcements, Captain Richie’s battery (two 6-pounders, one 5½-inch howitzer) (1e) and a detached gun from Captain Biddle’s command under Lieutenant Hall (one 12-pounder ) (1f).

2. Suffering increasing casualties the entire British line begins to recoil (2, 2a). This is escalated by the crumbling and partial retreat of the companies on both flanks (2b, 2c).

3. At the wood line, the remaining portion of the Twenty-Fifth Regiment (3) continue their push along the fence line (3a) in an attempt to outflank the 8th (King’s) Regiment (3b), forcing it to redeploy (3c), preventing it from supporting the main British line.

4. Deeper in the forest, the British light troops (4) continue their fighting retreat against the detached units of the Twenty-Fifth Regiment (4a), who call for additional reinforcements (4b), thus diminishing the threat on the British flank.

5. Recognizing his gamble has failed, Major General Riall orders a general disengagement and withdrawal. The main British line retreats (5) down the centre of the field. On the riverbank road, the 19th Light Dragoons (5a) cover the retreat of Armstrong’s artillery (5b) but are forced to use some of their horses to pull off the guns (5c). Sheppard’s battery also retires (5d), covered by the 8th (King’s) Regiment (5e).

6. As the American line does not immediately press forward in an attack, the British are able to reform and conduct a relatively orderly retreat: 100th Regiment (6), 1st (Royal Scots) Regiment (6a), Armstrong’s battery (6b), Sheppard’s battery (6c). The rearguard is composed of the 8th (King’s) Regiment in line (6d), fronted by a screen of troops in extended skirmish order (6e). On the flanks, detachments of the 19th Light Dragoons (6f, 6g) also provide rearguard cover.

7. As the main American line prepares to advance, the leading elements of Brigadier General Porter’s reformed Third Division (7) and Brigadier Ripley’s Second Division (7a) begin to appear from the wood line on the south west of the field, too late to join the action.

After detailing his aides to make a thorough reconnaissance and report, Major General Brown ordered his army back to its encampment to prepare for further operations the following day.

For his part, Major General Riall was now placed in the difficult position of reporting his defeat to his superior, Lieutenant General Drummond, and then up the chain of command to Prevost and Whitehall. His subsequent explanation referred to his attack as “not attended with the success that I had hoped for….”[6] While crediting the Americans for their improved quality of battlefield effort, Riall clearly attributed his reversal to an overwhelming number of American troops in their line-of-battle (estimating the American force at over 6,000 versus his own 1,800). By making this excuse, however, he conveniently chose to ignore the inherent contradiction of this claim in comparison to his original reasoning for initiating an attack on the Americans, instead of remaining securely on the defensive behind his lines at Chippawa. Not to mention the extended period of time his troops stood face-to-face with this enemy, exchanging volleys at point-blank range. In other words, if the Americans really had openly fielded that many troops in the first place, neither Riall, nor any other competent commander would have been so foolish as to attack them on their own ground. Likewise, had these “superior numbers”[7] appeared during the initial or even central course of the engagement, he would have gone on the defensive or broken off much earlier; recognizing the fact that he had absolutely no reserve to counterbalance the American advantage of numbers.

Fortunately for Riall, Lieutenant General Drummond recognized the calamitous effect this defeat of British regulars by an equivalent number of American troops could have on morale and the further prosecution of the war effort. He therefore chose to publicly support Riall’s line of reasoning of bravely fighting against overwhelming American numbers, as did Prevost. Privately, however, both senior commanders realized that this European-style collision of lines had produced the unexpected result of proving that the Americans were now fully capable of fielding an army that was able to contend with whatever the British had to offer — and the humiliating defeats and debacles of the American army over the previous two years were now things of the past.

OFFICIAL CASUALTY RETURNS,

BATTLE OF CHIPPAWA, JULY 5, 1814

American

First Brigade

Killed 2 musicians, 39 other ranks

Wounded 9 officers, 1 musician, 212 other ranks

Second Brigade

Killed 3 other ranks

Wounded 3 other ranks

Missing / Prisoners 2 other ranks

Third Brigade

Killed 3 other ranks

Wounded 2 other ranks

Missing / Prisoners 1 officer, 4 other ranks

American Native Allies

Killed 9–15 Warriors

Wounded 4 Warriors

Missing / Prisoners 10 Warriors

Artillery

Killed 4 gunners

Wounded 16 gunners

British Regulars

Killed 3 officers, 132 other ranks

Wounded 21 officers, 268 other ranks

Missing/Prisoners 1 officer, 30 other ranks

Canadian Militia

Killed 3 officers, 9 other ranks

Wounded 4 officers, 12 other ranks

Missing/Prisoners 15 other ranks

Cavalry

Wounded 6 other ranks

Artillery

Killed 1 other ranks

Wounded 1 officer, 4 other ranks

British Native allies

Killed 87 Warriors*

Wounded Number unknown

Missing / Prisoners 5 Warriors*

(*N.B. Due to the departure of the British Native allies immediately following the battle, this figure is derived from an American report and the killed total may well include Natives who fought for the Americans and who are mistakenly claimed as British losses, having lost their identifying head cloths during the fight. The same American report also claims to have inflicted casualties of a total of 10 officers and 298 other ranks upon the British.)

In response, both Riall and Drummond resolved to take the threat of the American army on the Niagara far more seriously. Drummond also recognized that he might need to take a more immediate and direct command of his troops if the military situation continued to deteriorate. For Riall, although he had regained his lines without contest and was temporarily secure, the shock of seeing his force beaten by an army that he had previously held in contempt undermined his resolve and caused him to react with excessive caution during the following weeks as the campaign developed. For both armies, the close-quarters, European style of battle had caused the expected heavy casualties.[*8] What was different, however, was that neither side could quickly obtain additional troops to replace their losses. Furthermore, the relatively small sizes of the contending forces meant that the death of dozens of men in a battle on the Niagara frontier carried the same strategic importance as that of hundreds on the battlefields of Spain, or thousands in Russia.