As the Roberts began its yard repairs in late 1986, the crew could be forgiven if they generally skipped the Portland Press-Herald’s wire stories about the Iran-Iraq war. There seemed little reason to suspect the frigate might somehow become caught in the bloody conflict, which had already ground on longer than World War II with little U.S. involvement.

Iraqi president Saddam Hussein had lit the flame in 1980, pouring troops across his eastern frontier to seize land and oil in the chaotic aftermath of Tehran’s Islamic revolution.1 But the incursion galvanized a divided country, and Iranian troops soon bludgeoned the invaders back to the border. Unfortunately for the region, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini proceeded to duplicate his enemy’s blunder by mounting his own push into Iraq. The Baghdad strongman rallied his war-weary citizenry, and the conflict soon devolved into a brutal stalemate, pocked with fruitless offensives and punctuated with missile explosions in crowded neighborhoods. In the first three years of war, some three hundred thousand Iranian troops and civilians died, along with nearly sixty-five thousand Iraqis.2

By 1984 Saddam wanted peace, but he could neither eject the Iranian forces nor swallow Khomeini’s heavy reparation demands. So he sought instead the aid of more powerful nations who might enforce a cease-fire. The Iraqi leader knew that long years of slaughter had not moved the West to intervene, but he thought he knew what would. The maritime traffic of the Persian Gulf included a steady procession of deep-draft oil tankers, whose capacious holds slaked one-tenth of the world’s daily demand. Saddam’s plan was simple: sink tankers, hurt oil-thirsty countries, and let them stop the war.

The strategy turned a sprinkling of maritime attacks into a new battle-front. In March 1984 a pair of shiny new Dassault Super-Etendards lifted off an Iraqi runway and headed southeast down the Gulf. Their wings bore Exocet missiles, the ship killers that had sunk a British destroyer in the 1982 Falklands War. South of Kharg Island, the pilots locked their radars onto a sea-level blip, let fly two missiles, and set a Greek tanker ablaze.3 Four attacks followed in as many weeks, all on ships bound for or bearing away from Iran. Tehran soon struck back in kind.4

The “tanker war” littered the shipping channels with burning vessels. Seventy-one ships were hit in 1984, 47 the following year, and 111 the year after that. Few of the big tankers actually sank, thanks to their spill-proofed double hulls, but dozens were declared total losses.5 Both sides preferred to sink enemy cargo, but one merchant ship looked much like another. Adding to the confusion, Iraq shipped its oil from ports in Kuwait and Saudi Arabia. The pillars of black smoke that rose above the hazy horizon frequently pointed back to neutral or even friendly craft.

Western action in the Gulf was long in coming, and it did not take the form Saddam had envisioned. In late 1986 the oil kingdom of Kuwait, tired of the attacks on its merchant fleet, asked Washington to provide naval escorts for its tankers through the war zone. American foreign policy toward the Persian Gulf might charitably have been described as muddled. Publicly, U.S. officials professed neutrality in the conflict. But Khomeini’s coup had transformed Iran, a staunch and well-armed U.S. ally under the shah, into a bitter enemy. The Reagan administration had tried to rally an international arms embargo—while secretly shipping U.S. weapons and gear to Tehran in attempts to free hostages elsewhere in the Middle East and to fund the Nicaraguan contras. Meanwhile, Washington had restored diplomatic relations with Baghdad in 1983 and had begun the covert supply of battlefield intelligence to Iraq.6

But the Kuwaitis proved better geopoliticians than Saddam. Even as Washington began to declare the request for a naval escort, the monarchy’s diplomats were inviting Moscow to do the job. The idea of Soviet warships protecting the world’s energy jugular was too much for the White House to bear. In March 1987, U.S. officials announced an upcoming series of convoys, to be dubbed Operation Earnest Will. The U.S. Navy had patrolled the Gulf since World War II. But this new effort would require a far heavier presence—as many as three dozen ships in and around the region.

The buildup had barely begun when disaster struck. One of the first new ships to arrive was the Stark, Cdr. Glenn Brindel commanding. Ten months earlier, Brindel had flashed a friendly message to Rinn across the tropical waters of Guantanamo Harbor. Now his frigate was on patrol in the middle of a war zone—and fairly relaxed about it. Neither the chaff launchers nor the Phalanx CI WS (close-in weapons system), an antimissile weapon, was turned on. The .50-caliber machine guns were unloaded, their gunners lying down near the mounts. In the combat information center, just one of the weapons control consoles was manned.

Just before sundown on 17 May, an Iraqi pilot in an F-1 Mirage jet headed down the Gulf, scanning his instruments, looking for tankers. In the Stark’s darkened CIC, an operations specialist picked up the Mirage on his screen: track number 2202, range two hundred miles, headed inbound. The jet was pointed past the ship, four miles off the port beam. The sailor passed the word to his skipper.

At two minutes after 9:00 PM, the Mirage locked its Cyrano-IV fire-control radar onto the Stark. The frigate’s instruments lit up in warning. A sailor asked permission to send a standard “back off” message to the Iraqi pilot. “No, wait,” came the reply.

At 9:05, the Mirage banked left, toward the warship. At just over twenty-two miles’ distance, the pilot launched his first Exocet. The missile leveled out a dozen feet above the waves, accelerated to nearly the speed of sound, and turned on its radar-homing seeker. Twenty seconds later, another Exocet dropped from a wing and lit off toward the Stark.

The ship’s tactical action officer later recalled no warning of the launches, though the ship’s radar and electronic countermeasures system were both built to sound such an alarm. The ship popped neither chaff nor flares. The Phalanx weapon—conceived, developed, and purchased for a moment such as this—remained in standby mode.

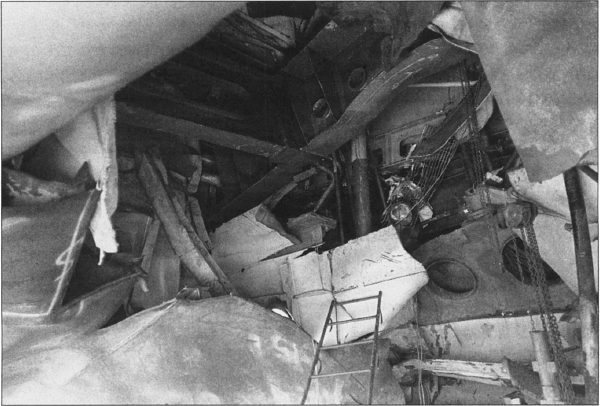

The first Exocet punched through the Stark’s hull near the port bridge wing, eight feet above the waterline. It bored a flaming hole through berthing spaces, the post office, and the ship’s store, spewing rocket propellant along its path. Burning at thirty-five hundred degrees, the weapon ground to a halt in a corner of the chiefs’ quarters and failed to explode. The second missile, which hit five feet farther forward, detonated as designed.

The fires burned for almost a day, incinerating the crew’s quarters, the radar room, and finally, the combat information center. Nearly one-fifth of the crew was incapacitated in the attack. Twenty-nine men were killed immediately; eight more died later.7

By the time the Stark was towed into Bahrain, a shaken U.S. Navy was already trying to figure out what had gone wrong. Why had the ship failed to defend itself? The service’s formal investigation blamed Brindel for failing to “provide combat-oriented leadership.” But the investigators also noted that the navy leadership had failed to sound the warning about accidental attacks from Iraqi jets. Instead, Gulf skippers had been told to keep a sharp eye for Iranian mines and admonished not to embarrass the United States by acting precipitously.8 One contributor to Proceedings wondered whether America’s naval service was breeding leaders who could handle a split-second switch from diplomacy to combat, saying: “The Navy’s natural selection during peacetime mirrors American society. We have always imagined a gulf between war and peace. We have attempted to separate cleanly our values and our behavior accordingly, and this has limited our effectiveness in a world of shadow conflict, or ‘violent peace.’ Even when we bridge that gulf and formally go to war, the mental transformation from gentility to the warrior’s ethic that demands unconditional surrender takes time. How long does it take the warrior to emerge?”9

The news of the Stark reached the Roberts at sea as it headed south for some exercises off the Virginia capes.10 The report shocked the crew. Many had a buddy aboard the Stark; some had acquaintances among the dead. Everyone knew the two frigates shared the same weapons, the same systems, the same vulnerabilities. Lester Chaffin, an electrician’s mate first class, studied the missiles’ paths and the damage done, and counted the shipmates who would have perished if the missiles had struck his own ship.

Rinn had known Brindel since their Naval War College days, and the classmates had renewed their ties at Gitmo the previous summer. “When I got that message, I sat on the bridge of the ship,” he recalled.

And the XO [executive officer], Bill Clark, came back about thirty minutes later. I hadn’t said a word to anybody, and he said, “Are you okay?” And I said, “No, I’m not. I’m sitting here thinking, ‘What twenty-nine guys would I would give up on this ship that I’d ever be able to sleep again?” Couldn’t do it; wouldn’t ever want to do it. So if there was anything that put a stamp on [my intensity], it was that I was never going to let that happen. How do you do it? How do you ever prevent it? You work as hard as you can.11

Rinn saw the Stark as the mistake of a guy who hadn’t been mentally ready. He vowed never to let an enemy take the first shot. Training aboard the Roberts, always intense, ratcheted up a notch.

IN JUNE 1987 the Roberts headed once again for Guantanamo Bay. A year earlier the crew had merely been confident. This time, they set sail with a gleam in their eye and a knife in their teeth. The frigate had aced its recent readiness exam, and its helicopter detachment had notched a flawless flight certification. The commander of the Atlantic Surface Fleet sent kudos: “Your DC material condition was the best ever seen by the inspectors, and your crew’s average score of 94 on the General DC Test has set the standard for others to follow.”12 At Gitmo, the Roberts crew intended to break every record in the book.

But the instructors were waiting for them. The curriculum that the Roberts had faced a year ago was among the casualties of the hellish chemical fires aboard the Stark. In the month since the attack, the damage control testers had devised more complex scenarios intended to put a warship’s crew in the Stark’s shoes. Roberts would be the first ship to face the new test.13

For three weeks, the crew moved through one exam after another with aplomb. The bridge watch notched the best seamanship and navigation grades in two years. Van Hook’s engineers ran through the comprehensive set of equipment-failure scenarios—then did it twice more just for practice. The frigate’s sonar operators locked onto the nuclear attack submarine USS Scamp (SSN 558) with helicopter and towed array, pounding away on the hapless sub for three extra days. Gitmo trainers deemed it the “the most impressive operation of its type held to date.”14

The big test, a “mass conflagration” drill, arrived on 14 July. The instructors arrayed themselves around the ship, ready to dock points for any missteps. At a whisper from an instructor in CIC, one of the operations specialists called out a warning: “Missile inbound, starboard side!” The Gitmo instructors clicked their stopwatches, and the game was on.

Rinn sent the crew to general quarters, but the “missiles” struck while hatches were still being dogged. The ship’s repair teams sprang into action as instructors around the ship narrated the scenario to grim-faced Roberts sailors. The first missile plunged into the ship’s exhaust stack, knocking out electrical power. The ship’s interior grew dim as fluorescent lamps went out and battery-powered battle lanterns came on. The roof of the starboard helicopter hangar collapsed. Class Alpha and Bravo fires erupted in the hangar bay and the midships passageway.

A second missile slammed into the ship moments later, exploding in the central office complex under the flight deck. The blast punctured decks and bulkheads, and thick black smoke spread inside the ship. A fire main ruptured. Main propulsion and communications followed electrical power into oblivion. The explosions “killed” or “wounded” just about everyone in the superstructure aft of the signal bridge; fantail, flight deck, hangars, central office, supply office—all gone.

Repair Lockers 3 and 5 leaped to work, with Rinn, Van Hook, and Sorensen in charge. The sailors diagnosed the damaged fire main and closed valves to stop the leak. They opened crossover connections to draw water from the undamaged pipes. They connected fire hoses and began to attack the blazes. They shored up failing bulkheads with wood and steel.

The instructors ratcheted up the pressure. Twenty minutes into the fight, the CIWS magazine atop the hangar deck blew up from the heat, further weakening the ship’s beleaguered superstructure. Moments later, the welding gases in an aft storage room exploded, blowing another six-foot hole in the side of the ship. That “killed” Rinn, and the instructor snarled at him with a look that said, “You’re an idiot for standing next to a flammable locker without moving its contents to a safe location.” It was a lesson he would not forget.

The instructors were merciless. They walked among the hose teams, sending scene leaders and nozzle operators to the sidelines with a tap on the shoulder and a terse “you’re dead.” Others they squirted with blood-red liquid, leaving them “wounded” for the corpsmen to save if they could. The imaginary toll was worse than the Stark’s; nearly one-third of the Roberts’s 165-member crew were pronounced dead. But the crew, cross-trained to a fare-thee-well, was unflappable. As chiefs and first-class petty officers fell, junior petty officers and seamen slid smoothly into their places.15 Through it all, Rinn kept the bridge and CIC teams in their seats, monitoring their surroundings for more attacks.

When it was over, the crew was winded but victorious. The instructors were a bit stunned. Their unanimous verdict: the Roberts sailors had saved their ship—and could have fought off more enemies as well. The senior tester praised the crew’s “originality and initiative,” “excellent crew participation,” and “superb leadership.” It was, he declared, the best mass conflagration drill he had ever witnessed.16

The Gitmo training commander tacked up a framed photo of FFG 58 outside his office and gushed about the ship to the three-star head of the Atlantic Surface Fleet. “The entire crew presented an eager, aggressive attitude and refused to let any problem set them back. Superior leadership and a keen sense of pride in their ship enabled them to function as a complete team,” he wrote. “USS Samuel B. Roberts departed GTMO as one of the best REFTRA [refresher training] combatants trained in years.”17

The Roberts would need all that expertise soon. Half a world away, the first Operation Earnest Will convoy was assembling on the far side of the Arabian Peninsula.

THE MV BRIDGETON, anchored off the eastern coast of Oman, defied the eye’s attempt to take its measure. The supertanker’s weather deck stretched a quarter mile from stem to stern and 230 feet across the beam. From time to time a Filipino sailor appeared on the rim of that vast steel plain, pedaling a bicycle on some errand. The ship’s double-bottomed hull could hold nearly 120 million gallons of crude oil, enough to keep Japan, the vessel’s birth nation, running for eight hours. For a decade the 413,000-ton tanker had gone by the name al-Rekkah and had reigned as the largest ship in Kuwait’s fleet—indeed, the biggest under any Middle Eastern flag.

The giant ship had recently surrendered that title, not because any larger contender had appeared, but because it no longer sailed under the Kuwaiti flag. Under the deal negotiated between Washington and Kuwait City, al-Rekkah and ten other Kuwaiti ships had shifted their country of registration to garner U.S. naval protection.

The crew of what was now the Bridgeton had marked the change in a ceremony in the Gulf of Oman, hauling the kingdom’s banner down the stern mast and running up the Stars and Stripes. The funnel, which had advertised the Kuwait Oil Tanker Company, already bore the red “C” of the Chesapeake Shipping Company. The new name had been painted over the old one on the stern, and the new home port lettered in white: Philadelphia. The ship would never visit its purported home; the river city’s piers were too shallow to accommodate its seven-story draft.18

The Bridgeton weighed anchor along with a reflagged liquid propane carrier, and four U.S. Navy warships fanned out around them. The nine-thousand-ton cruiser USS Fox (CG 33), the largest of the escorts, was a gnat beside the behemoth.

On 22 July 1987 the first Earnest Will convoy moved into the Strait of Hormuz and headed toward Kuwait, beginning a journey of nearly five hundred miles through a war zone. The seven-year toll on commercial shipping stood at 333 watercraft damaged or sunk, according to famed insurer Lloyd’s of London. The total for the year to date was 65.19

The Bridgeton was within a day of its destination when it became a naval statistic. Around 6:30 AM, the ship’s American skipper and his bridge team heard a distant metal-on-metal clank. Then the deck began to undulate. The sailors grabbed for the railings and hung on. “It felt like a five-hundred-ton hammer hit us up forward,” the ship’s skipper recalled.20 There was only one likely explanation: the tanker had hit a naval mine. But the leviathan was unable to stop—even emergency reverse thrust could not halt a supertanker in less than three miles—and the Bridgeton barreled on, making sixteen knots through a minefield. When the ship finally came to rest, the crew discovered a jagged hole the size of a squash court in the port bow. But the double hull kept the ship afloat. Soon the convoy was steaming onward to Kuwait, with one change in formation: the warships trailed Bridgeton in a meek line.21 None of the thin-skinned escorts dared break trail.

This was not the first live mine U.S. forces had found in Gulf waters. Mines had damaged at least one other commercial ship in the Gulf in 1987, and possibly two or three. About a dozen of the stealthy floating bombs had been detected and destroyed, but how many more were out there was anyone’s guess.

Stealth and simplicity made mines cheaper and often more cost-effective than just about any other naval weapon. During World War II, for example, U.S. submarines sank roughly five million tons of Japanese shipping, at an approximate cost of one hundred dollars per ton. By contrast, mines dropped by B-29 bombers in 1945 sent about 1.25 million tons of shipping to the bottom—and at one-sixth the cost per ton.22 Another statistic: in the half century after World War II, eighteen U.S. warships were damaged by hostile action. Fourteen of them hit mines.

Nevertheless, until the attack on the Bridgeton, naval leaders had remained largely complacent about the threat of mines in the Persian Gulf. It was a chronic oversight. U.S. Navy culture had long treated countermine operations as the ugly duckling of naval warfare. It was slow, painstaking, unglamorous work. And few admirals argued for spending money on bottom-search sonars instead of cruise missiles, fighter jets, and nuclear submarines.23

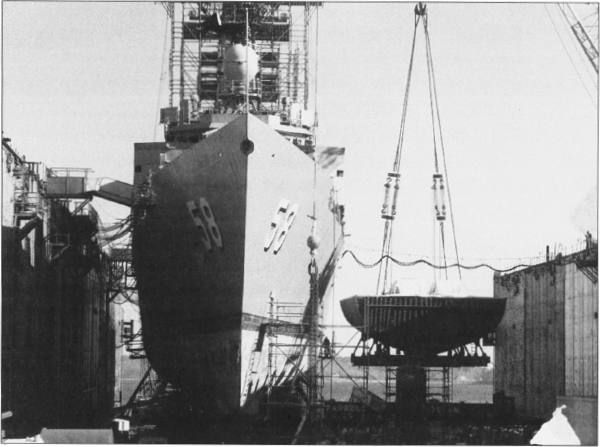

In the wake of the attack on the supertanker, the navy airlifted eight minesweeping RH-53D Sea Dragon helicopters to the Gulf. Four small wooden-hulled boats arrived a bit later on the back of an amphibious assault ship. But it took until late October for the navy to get its most capable mine hunters into action: six oceangoing minesweepers, none less than thirty-five years old, most relegated to the naval reserve, and so rickety that most of them were towed across the ocean to spare them wear and tear.24

Iranian officials, who had originally attributed the hole in Bridgeton’s hull to “the hand of Allah,” confessed to laying mines after another merchant ship mysteriously sank near the Strait of Hormuz. But Tehran insisted that its weapons were meant only for “coastal defense.” By autumn, shadowy U.S. forces would expose that as a lie.25

By September 1987 Operation Earnest Will was in full swing. Almost every day a U.S.-led convoy would depart from the Fujairah anchorage and head into the strait, while another group of tankers, bellies heavy with oil and gas, left Kuwait for the open sea. Many of the reflagged ships carried a U.S. liaison officer—generally a reservist called up from a civilian job, for the navy had not performed convoys since World War II and had no active-duty officers trained for the task. All told, the United States had nearly thirty warships in or near the Gulf, including the battleship USS Missouri (BB 63).26

But that was just the public face of the U.S. military operations in the region. The Pentagon also secretly dispatched an ecumenical group of elite forces: army special-operations helicopters, navy patrol-boat operators and SEAL commandos, marine security details. Operating under the classified code name Prime Chance, they set up shop aboard a pair of leased oil barges anchored in the northern Gulf. Mostly, they hunted armed speedboats operated by the Pasdaran, or Revolutionary Guards, a paramilitary organization whose naval role was attacking merchants with machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades.27

Operation Prime Chance was also meant to catch Iranian minelayers, and on 21 September, it succeeded. After nightfall, a pair of army helicopters lifted off from the frigate USS Jarrett (FFG 33), their pilots flying with night vision goggles. They zeroed in on a small amphibious ship, the Iran Ajr, that was creeping along about fifty miles off the coast of Bahrain. As the pilots watched, Iranian sailors dropped heavy objects the size of fifty-five-gallon drums into the water. The army pilots radioed their findings to the navy commander in the Gulf, who responded: “Stop the mining.” The pilots sprayed the ship with rockets and machine guns, and a team of navy SEALs stormed the deck. They gathered up an intelligence bonanza—minefield charts and nine M-08 mines—then scuttled the ship in deep water.28

The sinking of the Iran Ajr hardly slowed attacks on merchant ships. Three dozen were hit in September alone. On 16 October an antiship missile flashed from its launch container on Iran’s Fao Peninsula and struck the tanker Sea Isle City at anchor off Kuwait, blinding its American captain. It was the first attack on a reflagged ship since the Bridgeton, and it drew retaliation three days later. U.S. destroyers shelled a pair of defunct oil platforms that served as forward bases for Pasdaran speedboats. The chaos in the Gulf was getting worse.29

THE RUMORS STARTED on a rainy Veterans Day in Newport. A late-autumn drizzle forced an American Legion memorial ceremony off a trim park lawn and into the century-old city hall. As several dozen people rearranged themselves in the city council’s chambers, a navy commander in dress blues stepped to the lectern. The event’s organizers had invited Paul Rinn to make a speech, and characteristically, he had equipped himself with a relevant bit of history. The captain regaled his audience with tales of the 1st Rhode Island Artillery company at Gettysburg, and he asked listeners to remember the sacrifices of U.S. servicemen and women and the families they leave behind.

It was a moving speech—at least the editorial writers at the Providence Journal found it so. But an almost offhand remark by one of the speakers set tongues wagging across the waterfront: he wished Rinn and his crew smooth sailing in the Middle East. The next day’s newspaper carried a denial by Roberts’s executive officer that the ship had received any such orders. “The way it’s set up, you have to join the Sixth Fleet in the Mediterranean first, then we get our assignments,” Lt. Cdr. William Clark said. “If we’re ordered to the Middle East, we won’t know until thirty days prior to deployment.” But he added that the navy considered the guided-missile frigate “the best kind of ship for that environment.”

As for the crew, Clark said, “I think the overall attitude of the ship would be like if you were driving down the highway and saw a bad accident that just happened. You can feel the adrenaline pumping a little stronger, and you’re curious.”30

The XO was being cagey. He and Rinn had known differently for months. In late June the commodore of Surface Group Four had passed along a tip: the navy, in the wake of the Stark attack, had decided that every frigate once slated for a Mediterranean deployment would go to the Gulf instead. This required the Roberts to deploy in January, six months earlier than planned. “Know this news not the best you’ve heard today,” Aquilino wrote.

But now, despite Clark’s official denials, the cat was out of the bag. Everyone took the news a bit differently. Gunner Tom Reinert was phlegmatic. For one thing, he’d been predicting this for months. Moreover, he’d been to the Gulf twice already. His only disappointment was that his antisubmarine warfare team, which had worked so hard and received such praise, would be largely idle in the shallow Gulf, where no subs sailed.31

Others were not so sanguine. “In the late 1980s, the biggest fear for a young man just out of high school joining the navy was the possibility of finding himself on a ship in the dreaded Persian Gulf,” recalled Joe Baker, a fireman from New Mexico. “In civilian land, it’s like a rumor. But in the navy, people were talking about it all the time.”32

John Preston recalled one gunner’s mate who freaked out at the news: “I can’t go there, man!” The tension showed in frayed nerves and squabbles. Preston recalled the argument that broke out between two junior petty officers in a forward passageway. As he watched, the ship’s serviceman broke open a tin of red paint and dumped it over the engineman’s head, spattering the missile magazine, the passageway, and both sailors. Preston just kept walking. That looked like a fun cleanup, he thought.33

The crew took comfort in the knowledge that no ship on the East Coast was readier for battle. In recent exams, gas turbine inspectors had declared Van Hook’s team the best frigate engineering department they’d seen in two years. The aviation department earned the first flawless score the testers had ever issued. And in a no-notice damage control inspection, all three repair lockers received the highest possible grades—the best performance in the Atlantic Fleet.34 Palmer’s combat systems team was ready to go as well. Over the course of the year, the frigate had shot off an unusual amount of ordnance: five thousand rounds of small-caliber ammo, three thousand rounds of CWIS shells, three hundred 76-mm shells, a pair of Standard missiles, and two Mk 46 exercise torpedoes.35

Off the Massachusetts coast, the CIC crew had dueled with air force fighters until they could bring them down in their sleep. When the F-15s came out to play, Rinn had his radar operators dim their displays until the pilots radioed in from twenty miles out. The fighters would kick in the afterburners, drop to 250 feet, and go supersonic. When they flashed overhead, dragging a roar that could dissolve teeth, the sonic boom hit the ship like a hammer. Books plummeted from shelves; the hangar door fell off its hinges. But down in CIC, the fire controlmen had locked up the jet in plenty of time to greet it with a missile. To Rinn, that skill was worth any incidental damage by shockwave.36

DEPLOYMENT WAS SET for 11 January. The crew scattered across the country for the Christmas holidays and then returned for two hectic weeks of “packing the ship.” The engineers checked off a long list of spare parts and supplies: synthetic lubricating oil for the gas turbines, mineral oil for the reduction gear, acetylene tanks for welding, refrigerants for the air conditioners, nitrogen for the flight deck. They loaded rags, logbooks, and paper forms; citric acid to clean the ship’s freshwater distillers; canisters of bromine to make the water potable; and bales of cheesecloth to protect their machinery from the dusty Gulf air.37

Chief Cook Kevin Ford and his team of mess management specialists hustled to load their own refrigerated storerooms. In the rush, an order form typo brought the delivery of not one hundred, but one thousand five-pound bags of sugar—fully two and a half tons. An expert in the art of cumshaw, or barter, Ford had the extra sugar loaded aboard. He reckoned it might come in handy on deployment.38

A lot of new DC items arrived in the weeks before deployment. The Stark had revealed a need to keep smoke from spreading through passageways without obstructing firefighters. The navy had responded with smoke curtains—seven-pound, two-paneled drapes to be hung over hatchways. The service also sent a dozen portable radios.

Meanwhile, the crew stocked up on shoring beams. They obtained ten extra ten-foot four-by-four planks to add to their authorized issue of ten twelve-footers, and swapped six of their five-foot extendable steel supports for eleven-footers, giving them eighteen of the longer blue ones.39

The crew scoured the Newport waterfront for OBAs, the full-face masks that allowed firefighters to work amid the toxic fumes of a shipboard fire. The frigate was allocated 120 oxygen canisters—far too few.40 In Sorensen’s ten-page post-Gitmo memo, he had noted that the Roberts had expended their entire store during the mass conflagration exercise. When the exam ended, half of the sailors were wearing strips of masking tape labeled “OBA” in place of the real thing.

The Stark proved his point. Before it left for the Gulf, the crew had rounded up nearly four hundred canisters—and this had not been nearly enough. In the twenty-four hours that followed the missile strike, the crew used them all up—plus hundreds more flown onto the burning frigate from nearby U.S. warships.41 Sorensen recommended each frigate should deploy with no fewer than eight hundred canisters. The DC teams scrounged up as many OBAs as they could lay their hands on. Even parts and carcasses were stripped and rebuilt to add to the total.

Sorensen would have been proud to see the effort, but he was no longer aboard the ship. He had been rotated off as scheduled, and turned the job over to a replacement, Ens. Ken Rassler. The crew of the Roberts would face its deployment without their first DC leader. They also had a new executive officer; Clark rotated off and was replaced by Lt. Cdr. John Eckelberry, a veteran of several Gulf deployments.

Eventually, even the last-minute tasks were done. All the extra gear made for a very crowded ship—particularly since FFGs weren’t large to begin with, nor designed for extended patrols. The Samuel B. Roberts, mustering 215 souls and displacing 4,712.25 gross tons, was ready to go to war.42

ON 11 JANUARY 1988 Glenn Palmer awoke well before dawn. He switched on a light in his family’s Newport house, rolled out of bed, and headed downstairs to collect a last batch of laundry. Rachel, a three-year-old in pink flannel pajamas, was waiting at the top of the stairs. “Hold me, Daddy,” she said, and stretched out her arms.

For Palmer, preparing to sail meant preparing his family to stay behind. This would be his fourth deployment—he’d been to the western Pacific, the Mediterranean, even around South America. His wife, Kathy, and their three children had developed rituals to help bear the separation. A construction-paper chain hung in the kitchen of their Newport house, 184 links long. Each morning one of the kids would tear off a colored loop, marking the slow but steady passage of Daddy’s deployment.43

Putting to sea was always a risky business, and there had been plenty of tension during Palmer’s Cold War missions. But for the first time in their nine-year marriage, the couple had talked about what the family might do if Glenn failed to return. Things felt more dangerous this time—his ship was headed for a combat zone that had already taken the lives of thirty-seven U.S. sailors. There was another reason as well: Kathy was pregnant with the Palmers’ fourth child. The baby was due in March, which meant that Glenn would miss the birth—along with the couple’s wedding anniversary and the birthdays of their three other kids.

The couple had decided that if Glenn died, Kathy and the kids would move in with his mother. And with that, Kathy laid the matter in God’s hands. “I know there’ll be times when I’m depressed,” she told a newspaper reporter who was writing about the imminent departure of the Roberts. “The first time it’ll hit me will be when I have the baby, and I expect Glenn to bring me flowers and see the baby, and he won’t be there.” Palmer, the son of a minister and a graduate of a Christian college in Michigan, shared his wife’s faith and her sadness. “You can’t say you love people and say you want to be away from them for six months,” he said.

But there was another feeling, too: eagerness, an adrenaline trickle. It was a natural feeling of a naval officer in his twelfth year of service, especially one who had spent two solid years preparing himself, his ship, and his crew for a fight. The time had come to ride his warship into harm’s way. “This is basically what I’m getting paid for,” he said. “I’m putting my money where my mouth is. I’m not going to say I’m not afraid. But it’s a healthy fear, a respect.”44

The family gathered in the early morning darkness, and Palmer asked God to see them through their six-month separation. Then they climbed into the Caprice station wagon—little Rachel squeezed between her brother and sister in the backseat, her parents holding hands in front—and drove the five minutes to the naval station.

At the pier, Palmer embraced his wife and hugged his children. Then, as dawn broke, he turned and strode toward the gray form of his ship, dark against the cloudless sky.

Around him, shipmates were saying their own farewells. Most of the crew was already aboard ship; they were young and single, most from towns and cities far from Rhode Island, and had no one to see them off. Such was the final addition to the crew, Christopher Pond, a hull technician third class. Pond had slipped aboard just hours earlier—2:00 AM, as a matter of fact—and had received surprising news from the petty officer on duty at the quarterdeck. “You still have four more days of leave left,” the petty officer said, fingering a date on Pond’s transfer documents. “I would take it if I were you.”45

Pond had listened in disbelief. His orders had said nothing about his new ship’s imminent departure or its destination. A native of Lebanon, Pennsylvania, the nineteen-year-old was just back from a two-year tour aboard a support ship moored near the Italian island of Sardinia. The hull technician was still readjusting to life on American soil, and the idea of setting off on a six-month deployment before lunch arrived as something of a shock. For a moment, he was tempted to take his hard-earned leave and let the navy worry about getting him to the Roberts after it departed. Then he shrugged. Better to stay aboard than be shuffled around the world trying to catch up to my ship, he thought.

At 9:00 AM a navy band played “God Bless America,” and the frigate moved away from the pier. A small clot of family and friends waved as the ship headed out into the blue-gray Narragansett Bay. Moments later, another frigate pushed away from an adjacent pier: Roberts’s squadron-mate USS Simpson (FFG 56). One after the other, the warships passed beneath the long suspended span of the Jamestown Bridge, south past the rocky Dumplings, and out toward the Atlantic Ocean.

Left behind on the Newport pier was Aquilino. For eighteen months the commodore of Surface Group Four had guided and supported the Roberts as it proceeded from a newly commissioned watercraft to a deploying warship. Now he could only watch the frigate go with a mixture of pride, concern, and envy. Later that afternoon, he sent a message out to the departing ship, wishing them Godspeed as they headed for the closest thing the navy had to a front line.46

Three years of training had forged the Roberts’s two hundred and fifteen sailors into a fighting team. Thousands upon thousands of hours of preparation had honed their skills. But drills couldn’t compare to duty in the Gulf, where the action lasted not hours but days and weeks. And thoughts of Bridgeton, Sea Isle City, and Stark hung like specters in the salt air.