HOW WERE BLACK NEW YORKERS discriminated against?

In every way imaginable New York was a city where segregation (the separation of people by race) and disenfranchisement (a denial of a person’s rights) were a way of life. Black New Yorkers were second-class citizens.

An important example of disenfranchisement (and the way the term is usually used) involved the right to vote. Every state that joined the Union after 1819 denied blacks the right to vote. That didn’t change until 1870, when the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed. Prior to that, only in Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts did blacks have the right to vote without restriction.

In New York before 1821, both black and white men could vote if they owned $100 worth of property. After 1821, all white men—not just those who owned property—could vote, but black men had to own $250 worth of property. Since only a handful of black men in the entire state met that requirement, the vast majority were blocked from casting a ballot.

(Meanwhile, regardless of their race, women were not allowed to vote at all. The fight for women’s right to vote was a long and difficult struggle that didn’t succeed until 1920, when the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed. Even then, many black women were prevented from voting.)

Segregation meanwhile can occur in several ways. When dictated and enforced under the law, it is legal segregation, also called de jure or “under the law.” However, segregation can also be de facto (“in fact”), or by custom.

An example of de facto segregation occurred in public education in New York. An 1841 state law declared that all children age five to sixteen could attend a district school if they lived in that district. Yet black children did not often attend school alongside white children because the officials in charge were allowed to open separate schools for black children, and they often did. When it came time to distribute funds, schools for black children received far less money. They were “dark, damp, small, and cheerless” places, according to one newspaper account.

Another example of de facto segregation was in hiring practices. Many jobs, for example, were not open to blacks. Racist white employers simply would not consider hiring them, and there were no laws in place to make them do so.

Blacks who wanted to be professionals became ministers (a position then open only to men) or teachers. Only a small number of people were able to acquire the education needed to qualify for a teaching position. Elizabeth Jennings, according to one record, was one of just thirteen black teachers in New York City in 1855, and that number included men.

Those who dreamed of becoming bankers, doctors, or lawyers found it all but impossible. One educated young black man expressed his sadness and frustration. “What are my prospects?” he wrote in a letter that has often been cited by historians. “No one will have me in his office; white boys won’t work with me. Shall I be a merchant? No one will have me; white clerks won’t associate with me.”

Even the poorest white immigrants could rise from poverty faster than black New Yorkers. Not that it was easy, but it could be done, even with the burden of having to learn English. For blacks, education was not the key to success that it was for whites.

As a result, male black New Yorkers had no choice but to take the hardest and lowest-paying jobs, such as chimney sweeps, laborers, servants, mariners (working on the docks or on ships), barbers, coachmen, and cooks.

Black women had even fewer options. Other than peddling goods on the street, the most common ways to make a living were cooking, cleaning, and doing washing. Sometimes these jobs meant living away from their families. Those who were hired as live-in servants, for example, moved to their employers’ homes. The only time they spent with their own families was one day a week, on Sunday.

Even in churches there was segregation, with black worshippers often forced to sit in a balcony or on a back pew. Black New Yorkers responded by starting their own churches, including the First Colored American Congregational Church, on Sixth Street near the Bowery, where Elizabeth was headed on July 16, 1854.

Blacks and whites did not mingle openly except in the poorest neighborhoods, such as Five Points. Segregation in housing was common and on the rise. By 1852, 86 percent of black residents lived below Fourteenth Street, almost half of them in a single area that included parts of the Third, Fifth, and Eighth wards. The Jennings family home on Church Street was in the Fifth Ward. Three-quarters of Manhattan streets did not have any black residents at all. Black New Yorkers reported feeling stared at and uncomfortable in many parts of the city.

Theaters were segregated, with black patrons usually sold seats in a separate section far from the stage. There were stores where black New Yorkers were not welcome, and they were barred as customers from most hotels and restaurants.

And if blacks in New York wanted to take a streetcar, they encountered rules that forced them to ride on the outside of the car or to wait for one displaying a sign that stated COLORED PEOPLE ALLOWED IN THE CAR. The “colored” streetcars were often called Jim Crow cars, an insulting term used by whites to describe black people.

Jim Crow cars often came late, if they came at all. Conductors of cars meant for whites only (which did not carry a sign saying “white” but were simply unlabeled) would sometimes allow a black passenger to board if none of the white passengers objected—and if the conductor felt like it.

Segregated streetcars were a source of great frustration for black New Yorkers. As Manhattan expanded, the streetcar system became more important for getting to work. Each time Elizabeth, or any black person, needed to get somewhere by streetcar, the uncertainty surrounding the journey was stressful. Black New Yorkers could leave home early and still arrive late.

On that summer day Elizabeth, standing beside Sarah, was feeling that pressure. According to her own written account, all she wanted was to get to choir rehearsal on time. A streetcar finally came into view, and she held up her hand to signal the driver to stop. Although it was an unmarked streetcar meant for whites, she hoped the conductor would be understanding and let them ride.

With Sarah right behind her, she stepped up onto the platform, ready to make her case.

Jim Crow was the name of a character in a minstrel show, a type of performance in which a singer, accompanied by music, tells a story. While minstrel shows date back hundreds of years, the Jim Crow character, which depicted an insulting portrait of a black man, became popular in the United States starting in the late 1820s.

Jim Crow and the other minstrel characters were played by whites with their hands and faces blackened with soot. The popularity of minstrel shows in New York helped launch the Jim Crow character nationally.

Over time the term Jim Crow began to be used to refer to segregation. Streetcars in New York City meant for blacks were often called Jim Crow cars, according to the book Gotham, Edwin G. Burrows’s and Mike Wallace’s Pulitzer Prize–winning book on New York history. The term is most closely associated with racist laws that were passed to restrict blacks in the post–Civil War South. So-called Jim Crow laws created separate (and inferior) facilities in every part of society, including schools, hospitals, and transportation. Public rest rooms and drinking fountains in the South were labeled “Whites Only” and “Colored.”

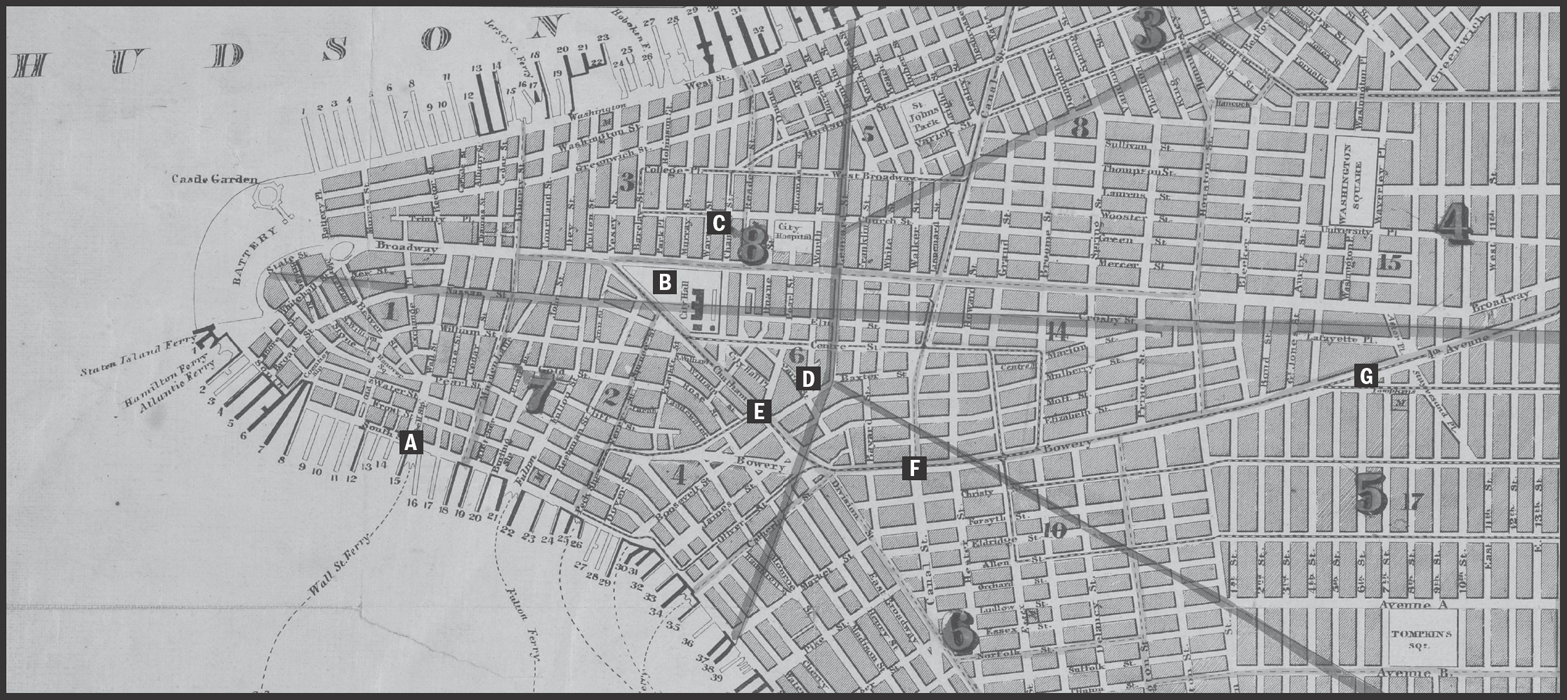

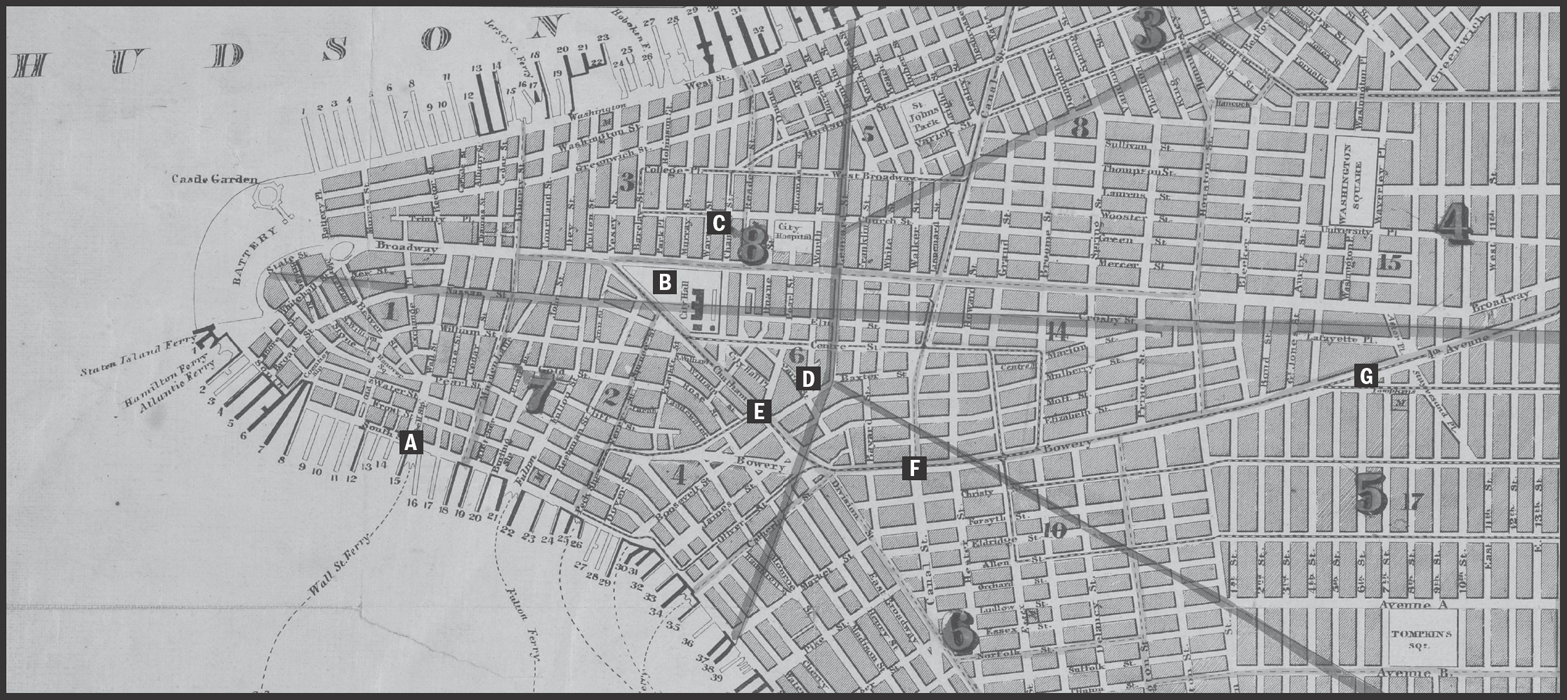

Manhattan Map 1856

A street map of lower Manhattan from 1856 showing:

A. New York’s Slave Market at Wall Street, which was in operation from 1711 to 1762.

B. City Hall.

C. The Jennings family home at 167 Church Street.

D. The center of Five Points.

E. The intersection of Pearl and Chatham streets, where Elizabeth and her friend Sarah boarded the streetcar. Chatham was later renamed Park Row.

F. The corner of Walker Street and the Bowery, known today as Bowery and Canal, where Elizabeth was ejected a second time.

G. First Colored American Congregational Church, on Sixth Street near Bowery, where Elizabeth had been headed on July 16, 1854.