A “Shameful” and “Loathsome” Issue

WORD SPREAD QUICKLY about the assault on Elizabeth Jennings, and an emergency meeting was called at the First Colored American Congregational Church.

Under doctor’s orders to stay in bed, Elizabeth was unable to attend the meeting, which was held on either July 17 or 18. “I would have come up myself, but am quite sore and stiff from the treatment I received from those monsters in human form yesterday afternoon,” she wrote. Her firsthand description of the assault was read aloud.

Thomas Jennings attended the meeting and added a few observations. What an emotional scene it must have been, with Elizabeth’s much-admired father standing in the front of the gathered congregation, speaking about his beloved daughter.

The meeting resulted in a decision: The incident was not going to be shunted aside or forgotten. Five people, including Thomas Jennings, were appointed to a committee that would study the facts and pursue justice.

The committee’s first step was to let others know about the assault. Elizabeth’s firsthand, written account was delivered to the offices of the New-York Daily Tribune, which published it under the headline OUTRAGE UPON COLORED PERSONS on July 19, 1854.

Adding to the frustration of Elizabeth’s supporters was the fact that segregation on the modes of transportation in the Northeast, not just New York City, was a long-standing problem. There were many reports of black travelers, both men and women, who were treated badly and unfairly on northern omnibuses, streetcars, railroads, ships, and steamboats.

Northern abolitionists, who were trying to find ways to end slavery in the South, were embarrassed by these incidents. They are “shameful in the extreme,” a white attorney named David L. Child, who belonged to an antislavery organization in Boston, Massachusetts, wrote in a newspaper called The Liberator. He was referring to the way blacks were treated by stagecoach companies and on steamboats throughout the North, not just in Boston or New York. His words were published in 1831, twenty-three years before Elizabeth Jennings was assaulted and ejected from the streetcar in New York City.

An article in an 1831 edition of The Liberator on the topic of segregation on modes of transportation in the North.

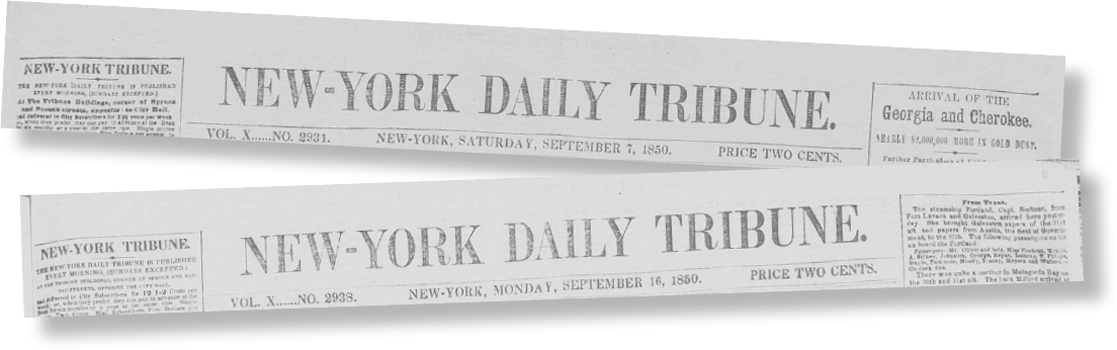

A lengthy commentary in the September 7, 1850, edition of the New-York Daily Tribune by an irate editorial writer who had witnessed an incident on a Manhattan horse-drawn streetcar.

Frederick Douglass wrote frequently of routine discrimination against black travelers. On steamboats that traversed the Hudson River, for example, he called the way in which colored persons were uniformly treated “brutal.” They are, he noted, “compelled sometimes to stroll the decks nearly all night, before they can get a place to lie down, and that place frequently unfit for a dog’s accommodation.”

IN THE FALL OF 1850 the New-York Daily Tribune published the story of an incident observed by an editorial or “opinion” writer, probably a white man. His name is not known. As was the custom with editorials, no byline was given.

The editorial writer had witnessed a conductor refusing to allow a black woman to ride on an uptown streetcar. “Stepping to the door to learn the reason . . . as there were but two or three persons in the car, we saw that the woman was copper-colored, either half or quarter African by descent, and were informed that this was the reason [she was removed],” he wrote.

He questioned the conductor, whom he quoted as saying, “Can’t help it, sir; the passengers make a fuss. . . .”

In a lengthy commentary the nameless writer voiced his belief that the treatment of the black woman was not the fault of the conductor or the streetcar company, but the “shameful” and “loathsome” general attitude in society toward black people. This attitude, he maintained, was left over from the days when slavery had been legal.

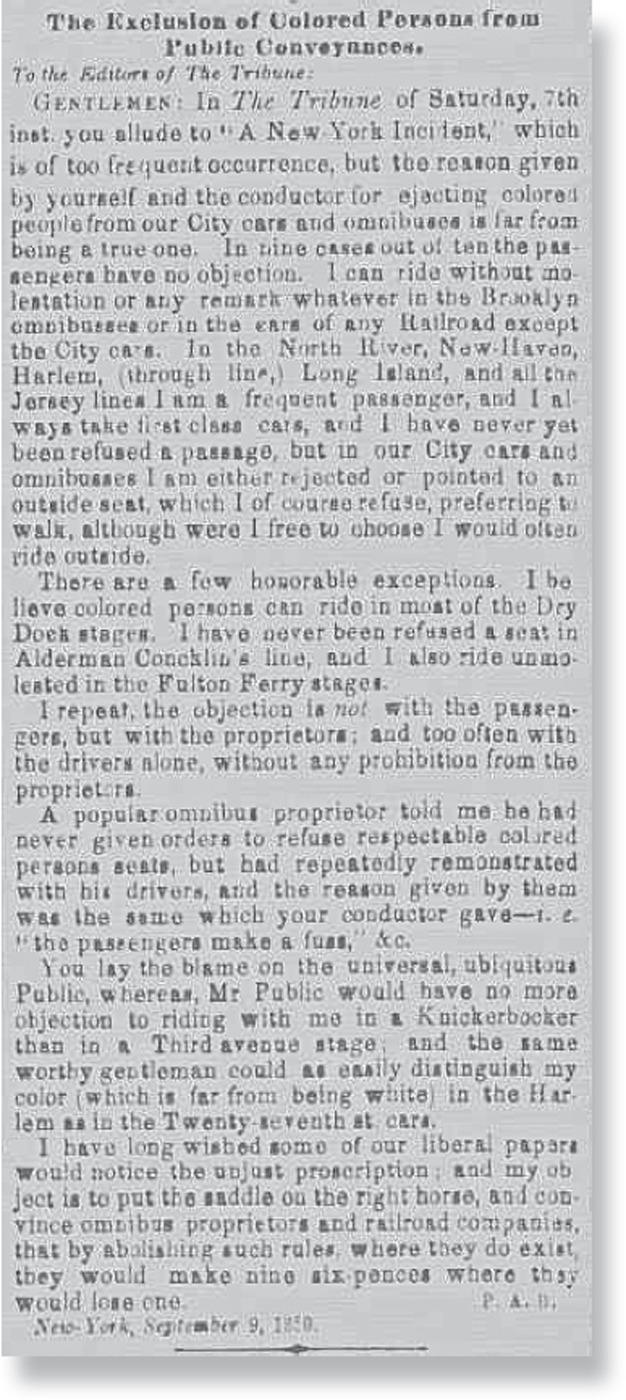

A letter to the editor in response to the commentary in the New-York Daily Tribune, September 16, 1850.

New York, the writer claimed, had fallen behind New England in addressing the issue of segregated transportation. “Africans are carried now the same as Whites throughout the greater part of New-England, though twenty years ago” it was “as brutal there as it now is here.”

He accused white New Yorkers of being hypocrites. “Let us purify our own borders before arraying ourselves in a grand crusade against the sins of our neighbors” in the South, he wrote.

Several days later a man who identified himself only by the initials P.A.B. wrote a letter in response. Because of the context of his letter, it’s clear that he was black. Wanting to share his observations, he noted that from his experiences it was not the passengers but the conductors who were responsible.

“In nine cases out of ten the passengers have no objection,” he wrote. “I can ride [without anyone objecting] in the Brooklyn omnibuses or in the cars of any Railroad except the City [Manhattan] cars. In the North River*, New-Haven, Harlem, Long Island, and all the Jersey lines I am a frequent passenger and I always take first class cars, and I have never yet been refused a passage, but on our City cars and omnibuses I am either rejected or pointed to an outside seat, which I of course refuse, preferring to walk. . . .”

Specifically, the letter writer stressed, the problem seemed to stem from individual conductors. He mentioned a conversation he’d had with the owner of an omnibus company who told him that he’d never given orders to refuse “respectable colored persons seats” but that his drivers often did so anyway, claiming, whether or not it was true, that “the passengers made a fuss.”

It’s clear that the issue of mistreatment of black riders on public transportation was not new in 1854 and had been much discussed and debated. What had happened to Elizabeth Jennings was another in a long line of incidents in which conductors insulted, pushed, and ejected black passengers.

Some white people in the North, upset by the treatment of black travelers, found small ways to show their support and fight for change.

The attorney David L. Child of Boston, Massachusetts, wrote, for example, about one small effort to pressure steamboat captains to treat black passengers fairly. Child, one of a group of eight white men who were delegates of the American Anti-Slavery Society, praised a white steamboat captain named Lewis Davis for his equitable treatment of black passengers. Child and his group had recently traveled together from Philadelphia to New York City partly on Captain Davis’s boat.

By calling attention in the press to Captain Davis, whose steamboat, Philadelphia, carried passengers between Philadelphia and Bristol, Pennsylvania, Child hoped to inspire other captains to act in a more equitable manner toward black passengers.

Child noted that the delegates of the American Anti-Slavery Society were willing to boycott other more convenient ways of travel in order to support Captain Davis.

“All of the . . . gentlemen were desirous . . . to go by the Rail Road Line, via Bordentown and Amboy,” wrote Child, “but they chose to take a circuitous,” or roundabout, “route, and a slower way of getting to their destination. They did this to show their appreciation of the captain of a boat who treated white and black travelers as equals.” Child added that Captain Davis’s competitors had lost business worth about twenty-seven dollars, which was what the men’s tickets cost.

Hoping that others would take note, Child publicized his account. His letter was published in the May 7, 1831, edition of The Liberator, where perhaps it inspired others to do the same.

William Lloyd Garrison and The Liberator

William Lloyd Garrison, founder of The Liberator.

“I am in earnest. I will not equivocate. I will not excuse. I will not retreat a single inch and I will be heard.” Those words were written by William Lloyd Garrison in the first issue of The Liberator, an antislavery newspaper he founded in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1831.

A white man raised in poverty in Newburyport, Massachusetts, Garrison became one of the most outspoken and passionate antislavery advocates in the United States. He didn’t write only about slavery, however. He was vigilant in condemning the inequality that free blacks in the North were facing. One of the issues he was concerned about was segregation in northern modes of transportation.

A newspaper editor by training, Garrison had grown impatient with the antislavery movement while working for two years as an assistant to Benjamin Lundy, a New Jersey Quaker and an antislavery advocate. Garrison despised the idea of gradual emancipation, believing instead that slavery should end everywhere immediately, and he also found that Lundy’s writings on the topic were too mild.

By launching The Liberator, Garrison altered the tone of the antislavery movement. In 1832 he started the New England Antislavery Society and, the following year, helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society.

Garrison received countless death threats but remained undeterred. He died in 1879 at the age of seventy-four.

Horace Greeley and the New-York Daily Tribune

Horace Greeley, founder of the New-York Daily Tribune.

Among large American newspapers, the New-York Daily Tribune was far from typical. The newspaper reflected the progressive outlook of its publisher and editor, a white man named Horace Greeley. He was born into a poor family in New Hampshire in 1811.

Greeley was a man with an opinion about almost everything, from vegetarianism (he was in favor of it) to alcohol (he was against it). He was well known for his strong antislavery views. He is said to have helped Abraham Lincoln get elected and afterward leaned on the president to declare the emancipation of enslaved people.

Disturbed by the influence of what was called the gutter press, which was a type of newspaper that focused only on sensational and outrageous stories, Greeley started the New-York Daily Tribune as an alternative. His newspaper was a success, becoming the largest in New York and perhaps all of America. Weekly editions were mailed to subscribers around the country. When Elizabeth Jennings was injured and ejected from the streetcar, the New-York Daily Tribune published her firsthand account on July 19, 1854, bringing the story to a wide audience that reached far beyond New York.

Another focal point for Greeley was the American West. He became famous for the iconic phrase Go west, young man, although he may not have been the first to use it. The town (now city) of Greeley, Colorado, was named after him.

Greeley tried his hand at politics, serving a short vacancy for a congressman who had resigned. He ran an unsuccessful campaign for president in 1872 and, in failing mental and physical health, unsuccessfully attempted to return to journalism. He died on November 29, 1872.