A VOLUNTEER at the First Colored American Congregational Church passed the hat that night from row to row, and people gave what they could afford to help the Jennings family pay for an attorney.

The black community was behind Elizabeth. But could a lawyer be found who would take the case?

It was a long shot. With very few exceptions lawyers were white men. It would be difficult to find one interested in taking on an equal rights case involving a black woman.

With few places to turn, members of the committee that was formed at the church to advocate for Elizabeth visited the office of a lawyer named Erastus D. Culver, a well-known abolitionist. Culver was sympathetic. He was deeply disturbed by the story and agreed that it deserved to be heard in a court of law.

But Culver had to turn the committee down. A year before, in the spring of 1853, he had been elected as a city judge in Brooklyn. He had turned over all his cases to a young lawyer in his practice. In an interesting twist of history, the newly minted attorney was Chester A. Arthur, who would one day be the twenty-first president of the United States.

But that was far in the future. The committee members who met Chester Arthur that day in 1854 were surely disappointed that they wouldn’t be able to hire Erastus Culver and were being asked to accept an attorney who was just twenty-four years old and who had been a lawyer officially for exactly six weeks.

New York City was growing rapidly. The population surged in 1855 to a new high of 629,810 because of immigration. Most of the newcomers were white and came from Ireland and Germany.

Meanwhile, the number of black residents of the city was on the decline, decreasing from 16,358 in 1840 to 13,815 in 1850. From 1850 to 1855 the black population dropped again, to 11,740.

The decline was caused in large part by the fact that blacks in New York City, as well as other northern cities, were increasingly in danger, and even more so following the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act.

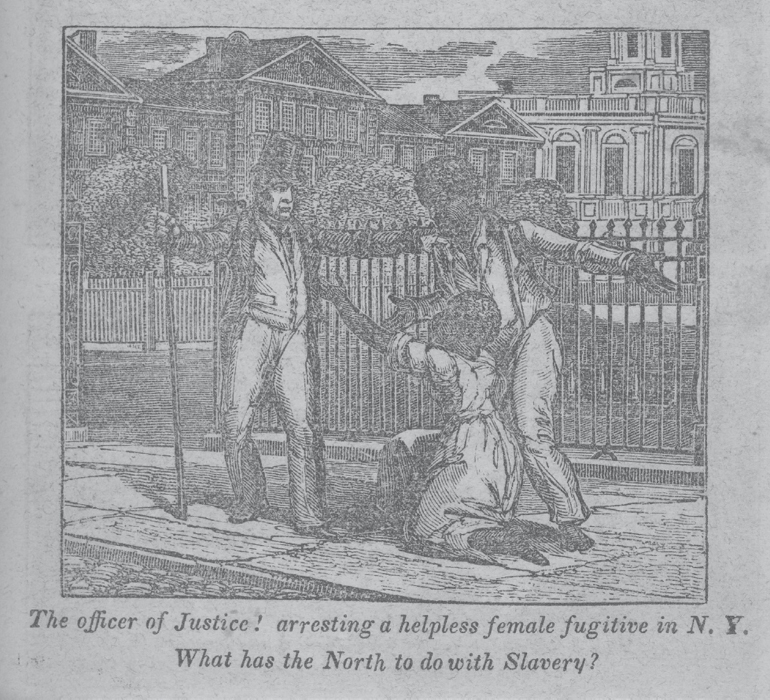

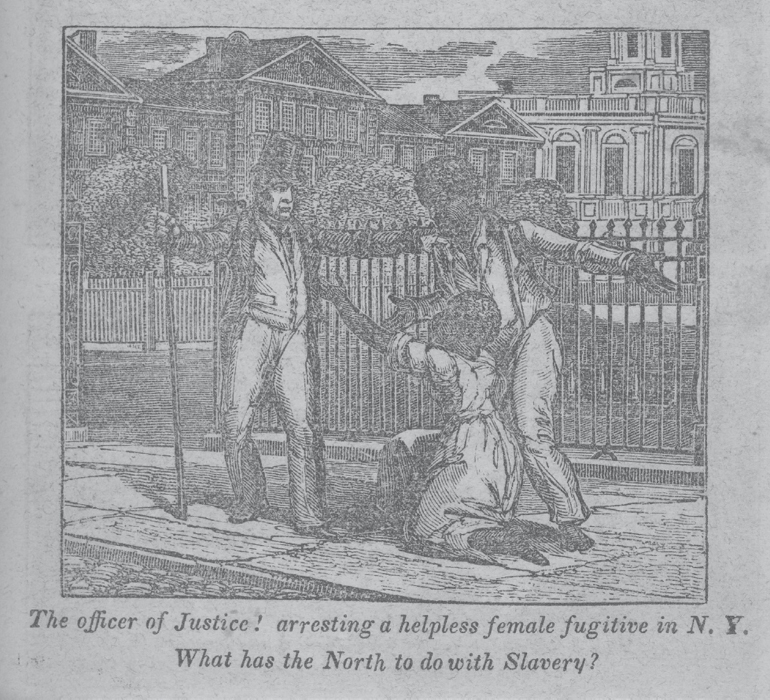

Signed into law in 1850 by President Millard Fillmore, the Fugitive Slave Act meant that runaway slaves who fled to the North could be captured and returned to the South. This included even those who had lived as free men and women in the North for decades.

Slave catchers were already doing a brisk business in New York, where runaway slaves could be found quickly because there were more leads in populated areas. Many blacks left the city and headed to farms or small towns in the countryside, where they hoped they would be undetected. A large number of blacks left the United States altogether and settled in Canada.

The new law instantly transformed free states such as New York from places where a runaway slave could count on a certain level of opportunity and safety to places where southern laws about slavery were enforced. Some historians believe that the passage and signing of the Fugitive Slave Act led America into the Civil War.

The new law also harshly punished those who helped to protect runaway slaves. New Yorkers played a major role in the Underground Railroad, a network of hidden routes and secret hideaways where escaped slaves received help on their journeys to freedom. Now sheltering fugitive slaves or simply interfering with their recapture put these antislavery volunteers in danger.

While there had long been the possibility that any black person, whether a fugitive or not, could be kidnapped, taken south, and sold to a slave owner, the new law made that scenario much more likely. Even someone like Elizabeth Jennings, born free in a northern state, faced this risk. Sometimes it was a case of mistaken identity. In other cases bounty hunters, motivated by greed, kidnapped the first black persons they encountered. Once they were in the South, there was little that could be done, although there were some cases in which money was raised and a kidnapped person’s freedom was purchased.

The capture of a black female fugitive in New York.

Yet Chester Arthur was impressive in his own right. He had earned the respect of Erastus Culver in a very short time. Chester had been an apprentice to Culver for the previous year, and Culver certified to the Supreme Court of New York that the young man was “of good moral character,” an endorsement that is still required (though described differently from state to state) before someone is allowed to practice law. Culver was so enthusiastic, in fact, that even before Chester Arthur was granted official permission to practice law, he’d been made a partner in the renamed law firm of Culver, Parker and Arthur.

Erastus Culver must have been very persuasive to convince the committee members that Chester Arthur could handle Elizabeth Jennings’s case. Arthur was very young, it was true, but he was extremely bright and hardworking. Culver won them over.

Chester A. Arthur: His Early Years

Chester A. Arthur was the fifth child in a poor white family that had strong antislavery views. His father, a Baptist minister named William Arthur, preached about the evils of slavery from the church pulpit.

William Arthur, who was born in the township of Dreen, County Antrim, Ireland, was so fiercely opposed to slavery that it led to problems in his career. Parishioners of a church he served in Greenwich, New York, from 1839 to 1844, for example, reported that he gave so many sermons on the topic that they grew tired of him.

He and his wife, a Vermont native named Malvina Stone, and their children relocated eleven times as he served churches in Vermont, western New York State, and the area surrounding Albany, New York, the state capital.

Chester A. Arthur was born while the family lived in Franklin County, Vermont. He was born on October 5, 1830, though some historians believe that it was a year earlier. (Some historians have also argued that Chester Arthur was actually born across the border in Canada. This would become an issue for him when he ran for national office because being born outside the United States would have disqualified him.)

In 1844 the family was relocated to the Albany, New York, area so that Elder Arthur, as Chester Arthur’s father was called, could serve as pastor of the First Particular Baptist Church and Society of Gibbonsville and West Troy. At last Elder Arthur had found a place where he was welcome. He became friendly with the faculty of Union College, including its nationally known president, Eliphalet Nott. The college in 1845 awarded Elder Arthur an honorary master of arts degree, coinciding with his work as editor of The Antiquarian and General Review, a magazine of “popular knowledge, covering history, philology, religion, and science.”

Young Chester was enrolled at Union College in September 1845. Often described as “amiable,” or friendly, Chester was well liked but not a great student. One teacher recalled that he was “frank and open in his manners, and genial in his disposition.”

For most of his college career Chester Arthur seemed more interested in having a good time than following in the footsteps of his serious-minded father. He was known to get into trouble for silly pranks, such as carving his name into wooden objects around campus or throwing the college bell into the Erie Canal. Having studied the French language and Greek and Latin philosophers, among other subjects, he was graduated from Union College in July 1848.

Chester Arthur did have one moment before he left Union College that revealed a serious side to him that would become more apparent when he went on to study law. He wrote an essay in which he argued that slavery infected the very soul of the nation itself.

What the committee members didn’t know, but would soon learn, was that Chester Arthur was as passionate about the rights of blacks as was Erastus Culver.

Still, the young attorney admitted privately that he was overwhelmed. He had little time for anything but work and rarely left the office, at 289 Broadway, or his room at a nearby boardinghouse.

Although he told friends he missed having a social life, he recognized that Culver’s faith in him presented a great opportunity that should not be wasted.

“It comes rather hard at first,” he wrote to his mother, “but it will do me a great deal of good.”

He had been given a chance to prove himself. But was he up to the challenge?