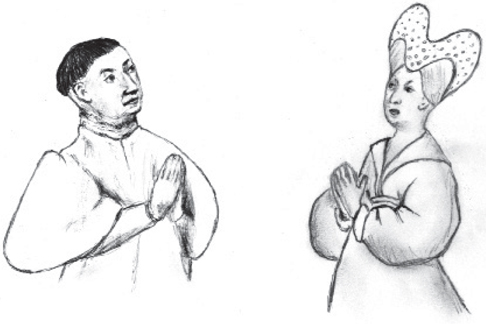

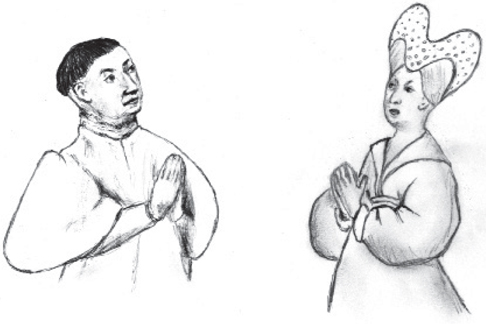

Eleanor Talbot’s parents, the Earl and Countess of Shrewsbury, at prayer. Redrawn from the Countess of Shrewsbury’s Book of Hours.

When the 55-year-old John, Lord Talbot, returned to England in February 1441/2, he had not set foot in his native land since 1435 – the year in which his daughter, Eleanor, had probably been conceived. It is therefore possible that he may never yet have set eyes on this latest addition to his family – the first daughter born to his current wife.1

Incidentally, for an explanation of the use, in this book, of year dates of the form 1441/2, it is important to understand that at this period the New Year in England did not start on 1 January. For this reason dates in January, February and March are here referred to under two year numbers, connected by a forward slash – such as 1441/2. The earlier year date (in this case 1441) is the one which would have been employed in the medieval period. The later year date (1442) is the modern version.

For the past seven years Talbot had been continuously in France, serving the cause of Henry VI. In 1431, this half-French king of England had also been crowned king of France at the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. It was Henry VI’s own cousin and representative in France, Richard, Duke of York, who had now dispatched Lord Talbot on a mission back to England. Talbot’s task in England was to plead with the king for more troops and more money to aid the faltering war effort. However, he may also have been glad to have occasion to visit his homeland on his own account, since he had private business in England; business which concerned his children.

It was the first Sunday of Lent, 18 February 1441/2, when John Talbot set sail from the Norman port of Harfleur, a town recaptured from King Charles VII eighteen months previously. He was accompanied by a deputation comprising Norman councillors, the faithful Richard Bannes, and five other men-at-arms from the Harfleur garrison, all of whom wore the Talbot livery.2 Lord Talbot had his own merchant fleet,3 and the vessel that now bore him across the Channel from Normandy may well have been one of his own ships. There was, as yet, no standing royal navy, and it was normal for private ships to be used in the king’s service.

Much of John Talbot’s life had been spent out of England, often in France, sometimes in Ireland.4 His family had served the house of Lancaster long before it attained the English throne. This allegiance even predated the creation of the Talbot baronial title, going back to at least the 1320s. John Talbot’s grandfather had fought in Spain for John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and it was in the service of the house of Lancaster that John Talbot himself had first gone to France.

He had been born in the reign of Richard II, before the Lancastrian accession to the throne.5 In the same year that he was born, his grandfather, the third Lord Talbot, had died in Spain.6 Then in 1396, when John was still only about 9 years old, his own father, the fourth Lord Talbot, had also died. As a result, a significant influence in John’s early life had been his stepfather Thomas Neville, Lord Furnival – the second husband of his mother Ankaret Lestrange.

John Talbot was one of Ankaret’s nine children by her first husband, Richard, fourth Baron Talbot. As the couple’s second son, he was not the direct heir to the Talbot title, which had passed, when their father died, to John’s elder brother, Gilbert. However, Ankaret’s decision to take a second husband after Richard’s death gave her an opportunity to promote the interests of her second son. Her new husband, Lord Furnival, had no son of his own, and Ankaret suggested that his daughter and heiress, Maud Neville, should be betrothed to John, who was thus placed in line to acquire the Furnival title when his stepfather should die.7

John Talbot is first known to have held a military command in the reign of Henry IV. That was in 1404, when he represented his stepfather patrolling the Welsh border after the battle of Shrewsbury. It was at about this time that John’s marriage to Maud Neville took place. This convenient arrangement paid dividends three years later, when his stepfather died and John Talbot inherited the Furnival title. In 1414 the new Lord Furnival was sent by the new king, Henry V, to Ireland as royal lieutenant. There Talbot quickly established a rather unattractive reputation for rapid response and for the calculated use of terror as a weapon.

It was also in Ireland, at Finglas, near Dublin, that on 19 June 1416 Maud Neville gave birth to John’s first known child, a son, baptised Thomas (presumably after Maud’s father). Thomas seems to have been a sickly child, and died some six weeks later.8 However, by 1419, when the family left Ireland, John Talbot’s second son, and eventual heir, John Talbot II, had probably been born, and perhaps also his third son, Christopher.9 It was also in 1419 that John’s elder brother, Gilbert, head of the Talbot family, died at Rouen, leaving only a daughter, Ankaret, to succeed him.

In 1420 Lord Furnival served briefly in France. However, he returned to England at the end of the year, having been appointed to organise the English festivities celebrating the coronation of Henry V’s bride, Catherine of France. John was one of the lords who served the new queen at the banquet in Westminster Hall following her coronation, while his sister-in-law, Beatrice, Lady Talbot – the Portuguese widow of his brother, Gilbert – was among the ladies honoured by being invited to sit at the table to the left of the queen. As organiser of the festivities, Lord Furnival may have been responsible for the menu served on that occasion, which comprised:

First Course

Brawn with mustard, eels in burneus,10 furmenty with bacon, pike, lamprey powdered11 with eels, powdered trout, coddeling, plaice with merling12 fried, great crabs, lesche lumbarde,13 a baked meat14 in pastry, tarts, and a subtlety15 called pellican, &c.

Second Course

Jelly, blandesoure,16 bream, conger, soles with myllott, chevyn, barbylle, roach, salmon fresh, halibut, gurnarde roasted, roget17 boiled, smelte fried, lobster, cranys,18 lesche damaske,19 lamprey in pastry, flampayne.20 A subtlety, a panther and a maid before him, &c.

Third Course

Dates in compost,21 cream motley, and powdered whelks, porpoise roasted, minnows fried, crevys of douce,22 dates, prawns, red shrimps, great eels and lampreys roasted, a lesche called white leysche,23 a baked meat in pastry with four angels. A subtlety, a tiger and Saint George leading it.24

When he returned to France, in May 1421, Lord Furnival probably left his wife pregnant (a pattern which often seems to have been repeated later, in the course of his second marriage). The birth of a daughter, Joan, probably in 1422, may have been indirectly responsible for Maud Neville’s death, in May of that year, at the young age of about 30.25 Maud’s was one of two deaths in the Talbot family at about that time. The other was that of little Ankaret, the Talbot heiress. As a result of Ankaret’s death, John finally succeeded to his family title of Lord Talbot.

To deal with the family business attendant upon the death of his wife and his own inheritance of the Talbot title, John returned to England in the summer of 1422. There, news reached him that Henry V had also died. This probably came as something of a shock, for the 35-year-old king had been about the same age as John Talbot himself. Henry had died at the Castle of Vincennes, just outside Paris, on 31 August 1422:

[The king had been] fighting a losing battle against a disease which his doctors could not identify – probably either a form of dysentery or a gangrenous fistula … The king’s sufferings were atrocious; his blood was poisoned and he had assumed a most terrible appearance, with lice crawling from his eyes and ear. … Instead of embalming the body after the king’s death, it was taken down to the ground-floor kitchens where it was cut up and the various parts put into an enormous cauldron over a fire … It was so well boiled that the flesh fell off the bones and these were then placed in a lead-lined casket with spices [to be shipped home to England].26

The sojourn in England of Lord Talbot and Furnival may not have been greatly welcomed by the royal council, governing on behalf of the new king, the infant Henry VI. John Talbot had already proved a somewhat turbulent subject, engaging in prolonged and violent disputes over precedence and over the inheritance of the honour of Wexford, with his cousins, the Earl of Ormond and Lord Grey of Ruthin. At all events, he was soon sent back to France, where, fighting at Verneuil in 1424, he earned himself the Order of the Garter.

It was probably towards the end of that year, perhaps on 6 September, that, in the chapel of Warwick Castle, he married his second wife, the woman who was to be the mother of his daughter, Eleanor. She was Lady Margaret Beauchamp, eldest daughter of the Earl of Warwick, and a lady some years his junior. Their first child, confusingly yet another John, was born in 1426.

Lord Talbot now returned briefly to Ireland, where, for the second time, he became the royal lieutenant. The following year, however, he was again back in France with the regent, the Duke of Bedford, fighting at the side of his new father-in-law Richard Beauchamp. There, he encountered Joan of Arc. With the exception of the regent himself, the dynamic and forceful Lord Talbot was apparently the only English leader in France whom Joan of Arc knew by name. At all events, she addressed a letter to him and to Bedford, telling them that they must withdraw and return to their own land. Lord Talbot was subsequently captured by Joan’s army at Patay in 1429, remaining a prisoner in France for several years. Prior to his capture, news may have reached him from England that, in his absence, Margaret had given birth to their second son, Louis – who was presumably named after Charles VII’s son, the Dauphin Louis (later Louis XI), who had been born six years earlier.

Eleanor Talbot’s parents, the Earl and Countess of Shrewsbury, at prayer. Redrawn from the Countess of Shrewsbury’s Book of Hours.

The custody of Lord Talbot was claimed by King Charles VII, who perhaps hoped to exchange him for Joan of Arc (captured by the Burgundians in May 1430, and sold by them to the English). If this was Charles’ plan, however, it was never realised. Eventually John Talbot was released as part of a mutual exchange of prisoners. He returned to England in May 1433, and was in the country long enough to leave Margaret pregnant once again. In July, Henry VI’s government sent him back to France, to serve with the king’s cousin, the Earl of Somerset.

Eventually, Talbot was appointed governor and lieutenant general in France and Normandy. In 1434 – at about the time that Humphrey (his third son by Margaret) was born – the king’s uncle, the Duke of Bedford, raised Talbot to the rank of Count of Clermont. Incidentally, little Humphrey was presumably named after the Duke of Bedford’s brother (Henry VI’s other surviving uncle), Humphrey of Lancaster, Duke of Gloucester. Subsequently John Talbot had made only one brief visit to his native island, in the summer of 1435. It was probably this visit that resulted in Eleanor’s conception and subsequent birth.

Although he had been born in England, Normandy was John Talbot’s ancestral home. Several centuries previously his ancestor, Richard Talbot, had first crossed the Channel from Normandy to England in the invading army of Duke William the Bastard. When the latter became ‘William the Conqueror’, Talbot – who was not in the highest rank of the new king’s supporters – had been rewarded with the grant of a single manor in Essex. By the accession of Henry II, Sir Richard Talbot, then head of the family, held the manor of Eccleswall in Herefordshire. Thereafter the family seems to have based itself on the Welsh border. In 1331, Gilbert Talbot was created first Baron Talbot by the young King Edward III.27

Richard, the son and heir of this first Lord Talbot, married an heiress, Elizabeth Comyn.28 As a result, the Talbot family inherited a fine new home: Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire. The castle’s grey keep dates from soon after the Norman Conquest, but the red sandstone outer walls and buildings were added in the reign of Henry III. By the time the Talbots acquired the castle, the Norman keep was little used, and the main residential quarters were the more modern great hall and its associated buildings.29 John Talbot’s father, Richard, renovated and improved the castle in about 1380, and in the fifteenth century, sturdy, moated Goodrich remained one of the principal dwellings of the Talbot family. In addition, however, the family had also acquired other, more up-to-date houses.

Perhaps as he travelled to England, John Talbot looked forward to revisiting his acknowledged favourite amongst the Talbot homes: Blakemere in Shropshire. He himself had been born at Blakemere, an estate which had come to the Talbots through his mother, the heiress Ankaret Lestrange.30 Blakemere was not, strictly speaking, a castle but a manor house, set in a fine deer park in which were three lakes. The largest of these was the Black Mere, from which the estate derived its name. Licence to crenellate the house had been granted on 14 July 132231 and thereafter it was sometimes referred to as a castle (castellum) although other texts continue to call it a mansum. The house lay to the eastern end of the southern side of the Black Mere, only yards from the lake, which (together with a little stream which still runs down to the lake on the western side of the site of the house) once fed the moat. Blakemere stood about a mile to the east of the town of Whitchurch, whose church tower is still visible today from the site of the house.

Nothing now remains of this favourite Talbot manor house. Still discernible, however, are the ditches that once formed its moat and, within the rough rectangle formed by these ditches, the raised mound where the house itself once stood. Fragments of dressed stone from the building still scatter the site. In the fifteenth century, Blakemere was a rich and productive property. Tenants maintained arable farming as well as both sheep and cattle. A dovecote supplied more than 1,200 pigeons a year for Lady Talbot and her household, and the forty-six beehives contributed more than 8 gallons of honey and 16 gallons of mead annually.32

John Talbot’s own, private business back in England, in the spring of 1442, concerned his children, and the inheritance claims of his second wife. Through her heiress mother, Elizabeth Berkeley, Lady Margaret claimed a share in the Berkeley inheritance. This claim was dear to the hearts of Margaret and John, both of whom were well aware that Margaret’s children – of whom there were now four – were extremely unlikely to inherit any part of the Talbot estates and titles. This was because these latter were entailed. Thus they would go to John’s eldest surviving son, John Talbot II, the child of his first wife Maud Neville.33

Already some seventeen years had elapsed since John Talbot had married Margaret Beauchamp.34 The eldest son of this second marriage, young John Talbot III, was now 16 years of age, and starting to make his own way in the world. The future of this son was probably one of the things in John Talbot’s mind, as he made his Channel crossing. Moreover, the Talbot family was still expanding, as John’s irregular visits to England continued to produce children. Little Eleanor, born probably about the end of February 1435/6,35 was the couple’s fourth child, and their first daughter. Perhaps as John Talbot made his journey back to England across the Channel, he also gave some thought to Eleanor, a child whom he had probably never yet seen. She would soon be 6 years old. He would be home in time for her birthday.