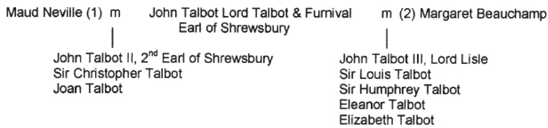

The two Talbot families.

By the beginning of the new year of 1443 (which, as we have seen, in medieval English terms commenced on Lady Day, 25 March), the family of John, Lord Talbot, first Earl of Shrewsbury, was complete, though the earl had yet to meet the latest recruit, the baby Elizabeth.

Next in age to Elizabeth, John and Margaret’s only other daughter, Eleanor, was just turning 7. Eleanor’s birthday probably fell in late February or early March, about two weeks before the end of the medieval English year. Eleanor would probably have been born under the sign of Pisces, and either by fate or by chance, she was to grow up with many of the characteristics traditionally ascribed to that star sign, for she was gentle, sensitive, idealistic and perhaps even somewhat passive. A girl who needed her own space, she would also ultimately develop a bent towards contemplation and mysticism.

Two years Eleanor’s senior was Humphrey, now nearly 9 years old. Their ages meant that, to a large extent, these three youngest Talbot children grew up together as a little group. Their ages, which united them, also distanced them to some extent from their older siblings, who were already almost adult when Elizabeth was born. Humphrey, Eleanor and Elizabeth were to remain close to one another throughout their lives.

The two Talbot families.

John’s and Margaret’s other two sons were both more than twice as old as Eleanor. Louis was 15 in 1443, while at 17 his brother John III was old enough for his parents to be planning his marriage, which took place later that year. It is questionable how well Eleanor really knew her two eldest full-blood brothers.

Relationships in the Talbot family were complicated not only by questions of age, but also by Lord Shrewsbury’s two marriages. More than three times Eleanor’s age were the members of the third and oldest group of Lord Shrewsbury’s children: those born to his first wife, Maud Neville. Three of Maud’s children had survived and reached adulthood. The eldest of these, John II, was heir to the earldom of Shrewsbury – much against the wishes of his stepmother, Margaret, who felt that the earldom, bestowed on her husband so long after the death of his first wife, should have been the destined inheritance of her own children. She, after all, was the first Countess of Shrewsbury!

A few years later, clear evidence would emerge that the relationship between the Countess and her husband’s eldest son and heir was strained. Such situations were by no means unusual in the fifteenth century. The antipathy between John II and his stepmother, coupled with a considerable age gap, may well mean that Eleanor had as little contact with her eldest half-brother as with her father. Even so, the relationship between the first Earl of Shrewsbury’s two families was subsequently acknowledged. This is evident from the fact that Eleanor’s brother, Sir Humphrey Talbot, who had been a Yorkist, left his property to Sir Gilbert Talbot, John Talbot II’s Lancastrian/pro-Tudor younger son.1

John II was already a knight, having been given that honour by the young Henry VI the year after Margaret had married his widowed father. He had been serving with his father in France, on and off, since 1436. In fact he had gone to Normandy the previous summer, when his father had returned there with the reinforcements. John II, now 30 years of age, had married, a little more than a year earlier. His wife was Catherine, the young widow of Sir John Ratcliffe, and daughter and co-heiress of Sir Edward Burnell of Acton Burnell in Shropshire. She was several years older than her new husband. To the medieval mind both the partners to this alliance were well beyond normal marriagable age. As yet there were no signs of any children from this union.2

Maud Neville’s third (and second surviving) son was Sir Christopher Talbot, also knighted by the king and about 23 years old in 1443. Maud’s only other living child was her daughter. Joan Talbot was about 21 years old in 1443, and it is possible that she too was by then married.3

The Earl of Shrewsbury also had at least one illegitimate son, Henry. It is not known whether he formed a normal part of the Earl’s household when at home in England, but in 1443 he may well have been serving with his father in France. Certainly, a bastard son of the earl was in France in that year, because one was captured by the French army, commanded by the dauphin, on 14 August 1443.

Noble children had to be educated, of course. Little girls had to be trained to be good future wives. They were also to be encouraged to form helpful social connections, first and foremost within their extended family. ‘From the age of about seven, the education of boys and girls began to diverge. Mothers continued to be responsible for their daughters, although among the nobility a mistres might be put in charge … Discipline for girls included physical punishment if this was thought necessary.’4 Chastity and obedience were highly prized commodities in daughters, and a key feature of their education was their religious training.

It is very clear from their later lives that both Eleanor and Elizabeth Talbot grew up with a sincere and lively faith that transcended mere conventional observance. This must reflect their upbringing. Religious training for children began at a very early age, and by the time she was 4 or 5 a little girl might be expected to be able to read the psalms in Latin.5 In 1463 it was noted that Sir William Plumton’s little granddaughter ‘speaketh [English] prettily, and French, and hath near hand learned her psalter’.6 This would probably have been mere rote learning. While both the Talbot sisters could read (and probably also write) English, and possibly French as well,7 their knowledge of Latin was probably confined to the reading of religious texts. There is no reason to suppose that either of them could write Latin. Such an accomplishment would have been very unusual for a noblewoman in the fifteenth century.8

There was, in fact, some debate in certain quarters regarding the advisability of teaching girls to read at all, but the majority of commentators seem to have been in favour of doing so, since ‘in practice, reading was a useful skill for women who in adult life might find themselves taking over estate and business responsibilities’,9 as the Countess of Shrewsbury certainly seems to have done.

On a practical level, aristocratic girls had to be taught to perform all the roles expected of successful wives. They needed to be literate in English, have some knowledge of arithmetic, receive hands-on training in household and estate management, and understand something about property law. Over and above specific skills, they had to learn to exercise authority over large numbers of people and take considerable initiative as mistresses of their households without violating their subordinate position.10

In addition to all this, ‘reading … freed the religiously inclined from the limitations of the rosary … [and] permitted the frivolous to read aloud from poetry and romances when no-one else was available to do so, an invaluable accomplishment on wet and windy days’.11

Writing, for girls, was a much rarer skill than reading. Even the women of the well-known (but slightly lower in terms of social status) letter-writing Paston family seem generally to have had their letters written for them by other people.12 It is impossible to say whether Eleanor and Elizabeth Talbot acquired writing skills. Almost certainly their surviving documents were written for them. Nevertheless, some aristocratic women did learn to write. Margaret of York was apparently able to do so, though she was initially brought up not as a king’s sister, but as the daughter of a royal duke.

In general there is a question mark over the degree of contact which normally existed between aristocratic children and their parents.13 However, the Countess of Shrewsbury does seems to have been available to take direct charge of the upbringing of her daughters, and her subsequent relationship with them remained close, suggesting that she had been personally involved with them during their childhood. There is no evidence that the Talbot girls were sent away for training in another aristocratic household before their marriages; nor does either of them seem to have spent any part of her childhood at court, in the household of Queen Margaret of Anjou, although noble children were sometimes sent to court in this way.

Eleanor and Elizabeth Talbot could not have had a better teacher for some of the skills they required than their powerful mother. They may also have had a governess, or maistresse, but if so her identity is unknown. Since governesses were usually not appointed until girls had passed the age of 7, and Elizabeth Talbot, at least, was married by that age, it is quite possible that they had none.

The Livre du Chevalier de la Tour, penned as guidance for his three daughters by a French knight in the late fourteenth century, suggests other possible priorities than literacy, numeracy and languages, which the Countess of Shrewsbury might have had for her daughters’ education. In this book, courtesy, deportment and a good reputation are all emphasised, as is obedience.14 Girls and women should certainly be suitably arrayed, but without immodesty or superfluity. Tinting the hair, or making up the face, was not to be encouraged.15 Chaucer, on the other hand, seems chiefly to have valued dignity in a woman, together with religious devotion, a command of French, and good table manners.16

Among the female relatives with whom the little Talbot girls might have formed childhood associations are their various female cousins. On her father’s side Eleanor had numerous cousins. Many of these, like some of her own siblings, were significantly older than Eleanor. Even so, there is clear evidence that these relationships were acknowledged.

Eleanor’s paternal cousins were the children of her father’s sisters. Of Lord Shrewsbury’s brothers only one, his elder brother Gilbert, is known to have had a child. This was the heiress Ankaret Talbot, who had died before Eleanor was born. Lord Shrewsbury’s sisters, in order of seniority, were Catherine, Mary, Elizabeth, Alice and Anne. Elizabeth (born c.1384) seems to have become a nun. The other four sisters all married – in several cases, more than once.

Catherine Talbot (born c.1378) married Thomas Eyton, of the Shropshire gentry. The Eyton family favoured the Yorkist cause, and Catherine Talbot’s younger son Nicholas (1400–c.1465), together with the latter’s nephew Roger (1420–c.1470), served as members of parliament. It is not clear whether Catherine also had daughters, but all her children will inevitably have been much older than Eleanor.

Mary Talbot (born c.1380) married Sir Thomas Green. She had several children, including a daughter, Joan. No evidence has so far been found as to whether Eleanor later maintained any kind of contact with the Greens, but they too seem to have been very much her seniors. Mary Talbot’s eldest son, Sir Thomas Green II, was born in 1400 and died in 1461, while his sister Joan was reportedly born in 1396.

Alice Talbot (c.1390–1436) married Sir Thomas Barre of Burford. She had at least one son and three daughters. Alice’s son, Sir John Barre (1412–83) served as MP for Herefordshire. He was a Lancastrian. Despite this, his daughter Isabel17 married Humphrey Stafford, whom Edward IV created Earl of Devon when the Courtenays forfeited that title by attainder. Sir John Barre’s eldest sister Elizabeth and his youngest sister Ankaret both married and had families,18 but most interesting is Sir John Barre’s second sister Jane (born c.1420?), who, like his daughter, also gravitated into the Yorkist camp. She became the second wife of Sir William Catesby I of Ashby St Leger (c.1408–78), and thus the stepmother of William Catesby II (1440–85), who has gone down in history as Richard III’s ‘Cat’.19 It is clear that Eleanor knew Jane Barre (Lady Catesby) and her family. As we shall see, Jane’s husband, Sir William, acted for Eleanor in matters of business. Jane had at least one child of her own, a daughter, Alice Catesby, born in 1447.

Anne Talbot (c.1395–1441) married Hugh Courtenay, Earl of Devon. Her son Thomas (1414–58) succeeded to his father’s title and married Margaret Beaufort.20 At this period the Courtenays were Lancastrians, and Earl Thomas’ two sons, who successively inherited the earldom, were both attainted and executed by Edward IV: Thomas (born 1432) in 1461, and John in 1471.

In addition to his full-blood sisters, Eleanor’s father also had a much younger half-sister, Joan Neville, born of his mother’s second marriage with Lord Furnival. Joan Neville married Sir Hugh Lokesey (died 1445). It is not clear whether this couple had children.

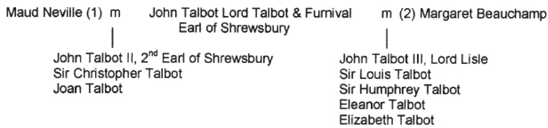

On her mother’s side were Eleanor’s Beauchamp relatives. Her aunt Eleanor had many children, including five daughters by her second husband, Edmund Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. These Beaufort cousins were Margaret, Lady Stafford (the mother of Henry, Duke of Buckingham – and it is interesting to note his blood relationship with Eleanor); Eleanor, Countess of Wiltshire; Joan, Lady Fry; Anne, Lady Paston; and Elizabeth, Lady (Fitz)Lewis. These girls were close in age to Eleanor and Elizabeth Talbot. That fact, together with the affection existing between their mothers, the Beauchamp sisters (not to mention the fact that their fathers were comrades-in-arms and colleagues in government circles), more or less guarantees that Eleanor knew the Beaufort girls well during her childhood.

There is clear evidence that Anne Beaufort, Lady Paston, maintained contact as an adult with her cousin, Elizabeth Talbot, Duchess of Norfolk. Indeed, she eventually married one of her own daughters into the Talbot family.21 Aunt Eleanor’s Beaufort sons, Henry, Edmund and John, were the last Beaufort Dukes of Somerset.22 As we have already seen, the elder of the two, Henry, was almost exactly the same age as his cousin, Eleanor. Later, after the advent of the Yorkist dynasty, these young male Beauforts were to prove somewhat dangerous relatives. Yet in spite of this, Eleanor’s sister Elizabeth seems consistently to have acknowledged their kinship.23 Aunt Eleanor also had children by her first husband, Lord Roos.

There is also circumstantial evidence of a connection between Eleanor and Elizabeth Talbot and their mother’s half-brother, Henry, Duke of Warwick.24 It is possible, therefore, that they knew his little daughter, their cousin, Anne Beauchamp, who died young. Of their other girl cousins on the Beauchamp side, Anne Neville (the future queen of Richard III) and her elder sister Isabel (the future Duchess of Clarence) were quite a lot younger than Eleanor and Elizabeth Talbot. However, they may well have known them.

Eleanor Talbot’s relationship to the Royal Family (simplified).

In June 1443 Eleanor’s father returned once more to England to plead with the English Council, which, instead of reinforcing the Duke of York in Normandy, was proposing to send a separate force into France, under Shrewsbury’s brother-in-law, Edmund Beaufort, now the Earl of Dorset25 Lord Shrewsbury had little success with this mission, and the Council could not be persuaded to alter its plans. By August, he had returned to Normandy. However, he probably saw his younger daughter for the first time, during this visit, and he may have been in England long enough to witness the marriage of his son, John Talbot III, to Joan Chedder, the 18-year-old widow of Richard Stafford. The bride was a year older than the young Talbot, and her father, Thomas Chedder, was but an esquire. Although Joan was one of his co-heiresses, this was not a wonderful match for a son of the Earl of Shrewsbury, and either it reflects the reality of John’s position as only the third surviving son of his father (with little hope of inheriting the earldom) or it must have been a mariage d’inclination on his part. The latter is a possibility, because at the time when he married, his mother was already working hard to have him raised to the peerage with a title carved out of her own maternal inheritance; an endeavour which bore fruit the following summer.

When the Earl of Shrewsbury returned to France at the beginning of August 1443, his second surviving son, Sir Christopher Talbot, remained behind and, in circumstances that remain somewhat mysterious, the distance separating John Talbot III from his paternal inheritance was suddenly dramatically reduced. Sir Christopher was killed, soon after his father’s departure, by one of his own men:

Griffin Vachan of Treflidian in Wales, knight ... struck to the heart and slew with a lance worth 2s. Christopher Talbot, knight, then his master, on St Laurence the Martyr, 21 Henry VI [10 August 1443] at Cawce, Co. Salop.26

Christopher’s death, at the age of only 23, brought John Talbot III one step nearer to the earldom of Shrewsbury. One wonders how the news of this stepson’s death was received by Lady Shrewsbury. She may have brought this boy up from a very young age. Nevertheless, he was not her own son, and his unexpected demise potentially benefited her own children.

On 26 July 1444 Margaret succeeded in her attempt to have her own first-born son raised to the peerage. Henry VI acknowledged (or created) him Lord and Baron Lisle of Kingston Lisle in Berkshire.27 By that time he had also received a knighthood. It was, however, probably not until the summer of 1448 that Joan, the new Lady Lisle, gave birth to John’s son, Thomas (named, perhaps, after her own father).28 Thomas was the Countess of Shrewsbury’s first grandson, and was born less than five years after her own youngest child, Elizabeth. Indeed, he was to prove her only grandson, for of all her children only John, the eldest, and Elizabeth, the youngest (and still a baby in 1444) were ever to produce children, and all of Margaret’s grandchildren except this first one were to be girls.

In France, meanwhile, another baby was baptised at about the same time as Thomas Talbot. Cecily Neville, Duchess of York, had given her husband a daughter, who, in September, was christened Elizabeth at Rouen Cathedral. The Earl of Shrewsbury, who had been working closely with the Duke of York for some time now, was chosen to be this little girl’s godfather.