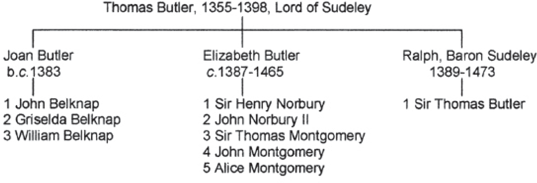

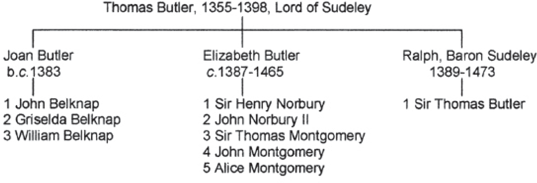

The Boteler Family of Sudeley – daughters.

Like Eleanor, Thomas Boteler also had a wider family. This included eight cousins, the offspring of his father’s two sisters: Joan and Elizabeth Boteler. By his aunt Joan, he seems to have had three Belknap cousins: John, William and Griselda, while his younger aunt, Elizabeth, provided Thomas with five more cousins: Henry and John Norbury, and Thomas, John and Alice Montgomery.

Aunt Joan Boteler’s marriage to Hamon Belknap must have taken place in about 1408 or 1409, when Joan would have been in her mid 20s. The couple produced two sons, John and William. In February 1428/9 following Hamon Belknap’s death, the care of his son, John, was committed ‘to Ralph Boteler, knight, John Monngomery [sic], knight,1 and Joan, late the wife of Hamon Belknap’. John Belknap is specifically stated to be Hamon’s son and heir, so he must have been the elder son.2 Nothing further is heard of him, however, so he presumably died childless, probably at an early age. The eventual Belknap heir was a younger son, William.

The Boteler Family of Sudeley – daughters.

In addition to John and William it seems that there was also a third Belknap child, for when Alice, the widow of William Boteler, Lord of Sudeley, was caring for the infant King Henry VI, she had amongst her ladies one Griselda Belknap.3 The surname is unusual and it seems logical to suppose that Griselda may have been Alice’s niece: a daughter of Joan Boteler and Hamon Belknap, and the sister of John and William. It is not certain what became of Griselda Belknap but the fact that Lord Sudeley’s elder stepson, John Hende III, married a lady called Griselda seems to be too much of a coincidence to be ignored. Probably John Hende’s wife was his stepfather’s niece, Griselda Belknap.

The remainder of Thomas Boteler’s cousins were the children of his younger aunt, Elizabeth Boteler, who had three husbands: Sir William Heron (Lord Say), Sir John Norbury and Sir John Montgomery.4 Some have argued that Sir John Norbury was Elizabeth’s first husband, but this is chronologically impossible.5 Elizabeth Boteler must have been married first to Sir William Heron, from whom she derived her title of Lady Say. She can only have married John Norbury after Lord Say’s death in 1404. There were no children from the Say marriage.

The relationship between the Boteler and Norbury families is complex, reinforced by two ties of marriage: first the marriage between Sir John Norbury I and Elizabeth Boteler, and then the marriage of Elizabeth Norbury to Ralph Boteler. Sir John Norbury I’s marriage to Elizabeth Boteler must have taken place in about 1405. On 1 June 1412 the manor of Cheshunt was granted by Henry IV to the Norburys, who by this time had two sons, Henry (the king’s godson) and John.6 Henry Norbury had been knighted by 1434, and married Anne Crosier, the heiress of the manor of Stoke d’Abernon, in Surrey. The tomb of his wife, Anne, with her brass memorial, is still to be seen in Stoke d’Abernon church, where there is also a Norbury chapel, founded by Henry and Anne’s son, Sir John Norbury III.7

On occasions, as in 1455, for instance, Sir Henry Norbury is found acting in association with his uncle (and half-brother-in-law), Ralph Boteler, Lord Sudeley.8 Possibly Henry survived his uncle to inherit the Sudeley estates.9 However, the fact that Henry Norbury’s wife Anne Crosier (who died in 1464) is shown on her tomb as a widow suggests that Henry died in about 1456–1460, at about the same time as his cousin (and nephew), Sir Thomas Boteler. Unfortunately there is scope for much confusion between Henry’s younger brother, John Norbury II, and Henry’s son, John Norbury III. John III could have been a knight by 1477, for in 1478 a Sir John Norbury occurs in association with Sir Thomas Montgomery, and thereafter was appointed the king’s vice marshal by Richard III on 8 April 1484, and received various commissions from that king during 1483–85, the last one being dated 2 August 1485, a mere twenty days prior to the battle of Bosworth.10 Despite some confusion as to which John Norbury is meant, these facts suggest that at least one of Lord Sudeley’s eventual heirs had no difficulty in accepting Richard III as king.

Another of Thomas Boteler’s cousins, Sir Thomas Montgomery, is well known as a prominent partisan of the house of York. The forebears of his father, Sir John Montgomery, had held land in various parts of England, but Sir John seems to have been the first Montgomery to make his home in Essex, settling at Faulkbourne, near Witham. Sir John served with distinction in the French wars, and received various titles and honours in the conquered lands, though of course these were lost later. He must have married Elizabeth Boteler, Lady Say, widow of Sir John Norbury, in 1415, and their first child, a son Thomas, was born in the following year.

Subsequently the couple had another son, John, and a daughter, Alice. All of these were first cousins of Sir Thomas Boteler. Like his brother-in-law, Lord Sudeley, Sir John Montgomery eventually returned to England. This must have been after 1442, for in that year his wife Elizabeth Boteler (who was with her husband in France) stood as godmother to the Duke of York’s newborn son – the future King Edward IV.

In 1445 and again in 1446 Sir John Montgomery was proposed for election as a Knight of the Garter, although on neither occasion was he actually elected, and the Montgomery family had to wait until 1477 to attain this particular honour in the person of John’s son, Thomas.11 Sir John Montgomery died in 1449, and his widow, the much married Elizabeth Boteler, Lady Say, in 1465.12

As an esquire Sir Thomas Montgomery’s name is found associated with that of Lord Sudeley’s stepson, John Hende the younger. Both men were marshals of the king’s hall and wardens of the mint in the Tower of London.13 During the reign of Henry VI, Thomas was called upon to escort Eleanor Cobham, Duchess of Gloucester, from Leeds Castle in Kent (where she had been tried for sorcery) to London.

Thomas’s brother, John, was executed by Edward IV in February 1461/2, for plotting against the Yorkist interest with Margaret of Anjou, the de Veres and Sir William Tyrrell. However, this did not blight Thomas’ career. He enjoyed Edward’s favour, fighting for him against the Lancastrians at the battle of Towton, as a reward for which Edward had dubbed him knight bachelor. Thomas’ loyalty to the house of York was so well known that he was immediately imprisoned by the Earl of Warwick upon the restoration of Henry VI. He was released a few months later, in time to meet the returning Edward IV and to help persuade him to drop his pretence of returning only to reclaim his duchy of York.

As well as serving as the king’s counsellor and virtually ruling Essex (receiving many of the manors of the exiled de Veres), Sir Thomas Montgomery enjoyed a distinguished diplomatic career. In 1474 he was sent to treat with the Emperor for an alliance and subsequently he met also with ambassadors of the King of Hungary. He was much employed in negotiations with the Duke of Burgundy, and was one of the many who escorted the wedding party of Margaret of York to Flanders in 1468.14

On this journey, if not before, he must have been much in the company of Elizabeth Talbot, Duchess of Norfolk, Margaret’s principal lady-in-waiting. He must also have known Elizabeth’s sister, Eleanor, who had been the wife of his deceased cousin, Sir Thomas Boteler. Moreover, Elizabeth Talbot (and possibly also Eleanor) was a close friend of Sir Thomas Montgomery’s sister-in-law, Anne (née Darcy), who, after the excution of her husband (Thomas’ younger brother, John) lived under Sir Thomas’ protection at Faulkbourne. Together with Lord Hastings and Lord Howard, Sir Thomas subsequently negotiated the Treaty of Picquigny. It was also Montgomery who was responsible, in the wake of this treaty, for returning the ex-queen, Margaret of Anjou, to France.

Richard III clearly trusted Thomas Montgomery, who is described in August 1484 as a ‘knight of the body’. In April of the same year Richard III had granted ‘for life to the king’s counsellor, Thomas Montgomery, knight, the castle, lordship and manor of Hingham’, and eleven other Essex manors, including Earls Colne, Hatfield Broadoak, Ongar and Harlow.15 It is not known whether Sir Thomas took any part in the battle of Bosworth, but initially he survived Richard III’s fall well enough to be called upon to hold the pall over Henry VII during the latter’s coronation. Thereafter, however, he faded rapidly from public life. Many of his manors, together with the castle of Hedingham, were returned by the new king to their former owners, the de Veres.

In any case, Thomas Montgomery was growing old by this time. He died in January 1494/5, probably a little short of his 79th birthday, and he was buried in the new Lady Chapel which he had built at the Abbey of St Mary Grace on Tower Hill, possibly to commemorate his brother who had been executed nearby. His two wives, Philippa Helion and Lora Berkeley, were buried with him, or at least, commemorated on his tomb. Philippa had originally been buried at Faulkbourne, but her body may have been brought to London to lie beside her husband’s remains. Certainly there is no extant memorial to her in the church at Faulkbourne. Sir Thomas’ tomb, like the abbey which contained it, is long gone, but his image, together with a representation of his sister-in-law, Anne, the great friend of the Talbot sisters, can still be seen amongst the stained glass donor portraits in the north aisle of Long Melford church, Suffolk (see plates 18 and 19). Sir Thomas Montgomery left no living descendants.16