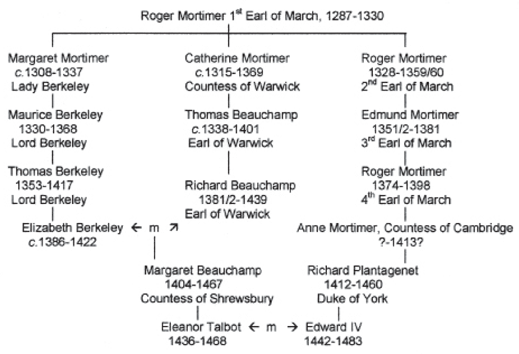

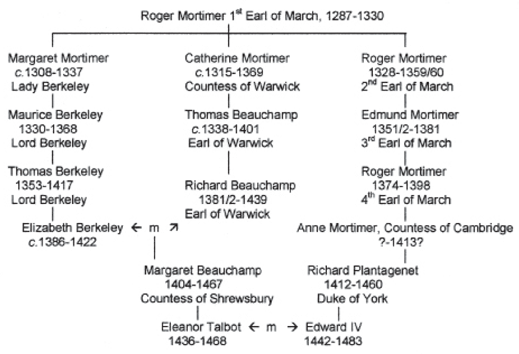

The common Mortimer descent of Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot.

Whatever part he may have played in the fighting of 1455–61, at the end of 1461 Ralph Boteler, Lord Sudeley was summoned to and attended the first parliament of the reign of Edward IV. He was by then in his late 60s, and possibly in indifferent health. The loss of his only son and heir had probably been a considerable shock to him. Subsequently, on 26 February 1461/2 Edward IV granted:

exemption for life of Ralph Botiller, knight, lord of Sudeley, on account of his debility and age, from personal attendance in council or Parliament, and from being made collector, assessor or taxer of tenths, fifteenths or other subsidies, commissioner, justice of the peace, constable, bailiff or other minister of the king, or trier, arrayer or leader of men-at-arms, archers or hobelers. And he shall not be compelled to leave his dwelling for war.1

When this exemption was granted, Ralph’s former daughter-in-law Eleanor was probably still intimately involved with the king. Indeed, it may well have been Eleanor who obtained the exemption for Lord Sudeley. She may also have been responsible for the royal grant, three months later, of ‘four bucks in summer and six does in winter within the king’s park of Woodstock’.2 It was perhaps also at about this period that Eleanor received her own mysterious grant of property in Wiltshire, which may have been a gift from Edward. The case for Eleanor’s involvement in Edward IV’s grants to Lord Sudeley is strengthened by the fact that, after she withdrew from her intimacy with the king, Ralph’s exemption was treated by Edward as a dead letter. Lord Sudeley was again appointed to commissions on a regular basis from the end of 1462.3 Though this may undermine one’s perception of the king’s kindliness, at the same time it also suggests that at that time he did not mistrust Lord Sudeley’s loyalty.

Previously, there have been varying interpretations of the significance of Edward IV’s apparently contradictory actions in respect of Lord Sudeley. This offers just one small example of the kind of problem that arises when one tries to explain the events of this period without taking account of Eleanor. Unfortunately, no earlier writer had noted the significance of the fact that Edward’s kindliness dated from the period when Ralph’s daughter-in-law was the king’s partner. Some therefore speculated that the king may simply have been seeking a pretext for removing Ralph from Parliament. However, the Complete Peerage refuted this: ‘The suggestion that Edward IV was hostile to him is weakened by this exemption, and by a grant in 1462 for life of bucks from Woodstock, and a general pardon for trespasses and debts in 1468.’4 We shall return later to Lord Sudeley’s pardon of 1468, which is incontrovertibly connected with Eleanor.

Edward IV’s actions in respect of Lord Sudeley imply that the king’s relationship with Eleanor lasted into 1462. While their secret seems to have been very well kept by both parties, and even though Eleanor seems to have very successfully avoided (or been kept out of) the limelight, clearly there were rumours. In a political poem in support of Edward IV, written after his return to London, following the battle of Towton and his marriage to Eleanor, we find the following curious verse:

The Rose wan þe victorye, þe feld and also þe chace,

Now may þe housband in the southe dwelle in his owne place;

His wife and eke his faire doughtre, and al þe goode he has,

Soche menys haþ the Rose made, by vertu and by grace.

Blessid be the tyme, þat euer God sprad that floure!5

Later, vague references to a relationship between the king and a relative of the Earl of Warwick were reported by both Mancini and Vergil. Perhaps it is not surprising that Eleanor should have been referred to, and later remembered, in that oblique way. Although her dead father had been famous, she herself was a virtually unknown figure in 1461–62. Of her close living relatives the highest in rank was her sister, who had just become Duchess of Norfolk. But, at that time, by far the best-known and most important of Eleanor’s living relatives was undoubtedly her uncle, Warwick.

It is possible that it was through Eleanor that Edward met the daughter of Thomas Wayte, who was to be one of Eleanor’s female successors in the royal bed. Eleanor’s land in Wiltshire was contiguous with a manor belonging to the family of Elizabeth Skilling, the wife of Thomas Wayte. Curiously, however, Edward IV’s relationship with Eleanor Talbot seems to have been superseded not by a royal mistress but by a same-sex relationship between Edward and his second cousin, Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset. Ironically Henry Beaufort was also Eleanor Talbot’s own first cousin, for their mothers were sisters. Possibly this new same-sex relationship of Edward IV may have been the incentive which, some six to eight weeks later, brought about Eleanor’s decision to take religious vows as a Carmelite tertiary. Like Edward and Eleanor, Edward and Henry may possibly have met on certain occasions earlier in their lives. However, their key meeting in terms of their intimate relationship took place in 1462, when the Lancastrian Duke of Somerset surrended Bamburgh Castle to Edward’s forces on Christmas Eve.

As Gregory’s Chronicle reports, following this meeting these two young men regularly slept together and the king was said to love the Duke of Somerset. The logical conclusion appears to be that Edward IV and Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, regularly indulged in sexual intimacy of some kind. Apparently the two young men remained together for about six months – until July 1463 – and possibly a little longer.6

Although Henry Beaufort is said to have produced an illegitimate son at some stage in his life, he definitely never married – though, of course, attempts were made to arrange a marriage for him. There is also some evidence that he may have had same-sex relationships with other contemporary dignitaries prior to his reported relationship with Edward IV.7 A previous possible lover of Henry was Charles the Bold, who at the time of his meeting with Henry had been the Count of Charolais. Later, of course, Charles succeeded his father to the Duchy of Burgundy. He also entered into three successive marriages, the third of which was with Edward IV’s sister, Margaret of York. Nevertheless, Charles produced only one child, and he has been described as homosexual.8

Ironically, Henry, Duke of Somerset, was not only the second cousin of Edward IV. As we saw earlier, he was also a first cousin of Eleanor Talbot, who probably knew him well. Henry’s mother, Eleanor Beauchamp, was a younger sister of Margaret, Countess of Shrewsbury, and may have been one of Eleanor Talbot’s godmothers. Moreover, Henry may have resembled Eleanor in some aspects of his appearance. It certainly seems that he shared the attractive good looks for which his female Talbot cousins, Eleanor and Elizabeth, were celebrated. One contemporary chronicler, who had met Henry on the mainland of Europe, described him as ‘a very great lord, and one of the most handsome young knights in the English kingdom’.9

The Duke of Somerset seems to have been a rather quick-tempered young man, making him sometimes rather a difficult person to deal with. Nevertheless, Edward IV was apparently very well able to get Henry to relax when he was feeling stressed. For example, in March 1462/3, when Edward arranged a joust in which Henry took part, the Duke of Somerset began behaving in a rather angry manner. However, with no apparent difficulty, the king overcame Henry’s incipient ill humour on that occasion. He merely requested the duke to be merry, and offered him a little present.10

Ultimately, however, the relationship between the two men appears to have aroused popular anger against the Duke of Somerset. As a result, he and Edward found themselves forced apart, after which Henry deserted Edward and returned to his traditional Lancastrian allegiance.

Meanwhile, as we have seen, Eleanor Talbot had moved in a religious direction – possibly influenced by the dubious morality of Edward IV’s relationship with her cousin, Henry. The collapse of her own intimate relationship with the young king meant that there was now no longer any chance that he would ever publicly recognise his secret marriage with her. However, Edward took no action to officially end their relationship.

Although he and Eleanor were both fourth and fifth cousins once removed – owing to their common descent from Roger Mortimer, first Earl of March (see opposite) – that blood relationship was not close enough to be significant in terms of the legality of their marriage contract. At a much earlier period the couple would not have been allowed to marry without a papal dispensation. However, at the Fourth Lateran Council in 1215, Pope Innocent III had restricted the impediment of consanguinity to the fourth degree of kinship (third cousins).11 Indeed, the fact that no dispensation seems to have been provided for the marriage of Eleanor’s maternal grandparents, the Earl and Countess of Warwick – who were more closely related, and whose alliance did fall within the prohibited degrees of kinship – suggests that Eleanor and Edward’s families may well have been unaware of their common Mortimer descent. It is doubtful whether a Church court would have considered the impediment of consanguinity sufficient to invalidate even the Warwick marriage. In the thirteenth century, for example, when the marriage of Sir Walter de Beauchamp had been called into question because he was related in the fourth degree to his wife, the Bishop of Worcester had ‘decreed that their marriage was lawful … as they were ignorant at the time they contracted the marriage that there was any impediment between them’.12

The common Mortimer descent of Edward IV and Eleanor Talbot.

The king certainly never tried to take advantage either of consanguinity or of any other grounds to seek an annulment. To do so, of course, would first have required him to acknowledge the existence of his marriage. While this might conceivably have been a possibility from 1461 until 1463, once Edward had compounded the complexity of the situation by contracting a second secret marriage, any formal acknowledgement of the first was out of the question. He was then committed to a policy of silence. Indeed, in respect of the Talbot marriage Buck asserts, very credibly, that ‘he held them not his friends nor good subjects which mentioned it’.13

Eleanor, for reasons of her own, also seems to have elected to maintain a dignified silence, at least as far as the world in general was concerned. Being a rather private person, she shunned any publicity, lived in retirement and cultivated religion.14 It was also probably the case that, for a devout lady such as Eleanor, Edward’s subsequent conduct with a mistress and with her own first cousin, the Duke of Somerset, had proved somewhat shocking.

How much Elizabeth Talbot knew at this time of the relationship between her sister and the king is uncertain, but later, when Eleanor had been abandoned by Edward, she may have spoken of the affair both to Elizabeth and to their mother.15 Elizabeth’s subsequent relationship with her sister arguably shows a protective streak which may have arisen out of some sense of responsibility for the fate which had befallen Eleanor. The relationship of the two Talbot sisters appears to have been a close one that lasted well beyond the grave. When Elizabeth was in her 50s, her sister Eleanor – then already thirty years dead – was still very much on her mind. This is proved by Elizabeth’s touching concern in the 1490s to make an endowment for the good of her sister’s soul – an endowment which, by that time, she could not really afford, and for which, in the end, she had to pay by instalments.

But Edward and Eleanor were not the only people who knew of what had passed between them. There was at least one other. Canon Robert Stillington was keeper of the privy seal in 1461 and held a number of ecclesiastical appointments,16 but he was not yet a bishop. Edward, however, favoured him towards the end of 1461 to the extent of awarding him an annual salary of £365,17 and it will be instructive at this point to consider the circumstances of Stillington’s subsequent appointment as Bishop of Bath and Wells.

As we have already noted, essentially ‘Stillington’s career is that of a politician rather than that of an ecclesiastic’.18 ‘Bishoprics were frequently used … to reward officials without depleting the limited supply of crown lands.’19 Despite this, it is noteworthy that when the see of Carlisle became vacant a few months before the Widville marriage was made public, Stillington was not nominated for that post. Edward IV only seems to have marked Stillington for episcopal preferment from mid September 1464 – the time when the king’s subsequent Widville ‘marriage’ was brought into the open (see chapter 16). Although the Archbishop of York had then recently died,20 the king had probably already earmarked this appointment for Warwick the Kingmaker’s brother, George Neville, Bishop of Exeter. In any case, since Stillington had not previously held a bishopric, the metropolitan see of York would have been a considerable promotion for him.

No English bishoprics fell vacant in the last months of 1464 (in terms of the modern calendar), though there were vacancies in several Irish sees and one Welsh see. In fact, the next English bishopric to fall vacant after the announcement of the Widville alliance was that of Bath and Wells, which became available following the death of Bishop Thomas Bekynton on 14 January 1464/5. Royal licence for the election of a successor was issued on 19 February.21

It seems evident that Edward IV was then waiting for such a vacancy in the episcopacy in order that he might award it to Stillington. He clearly intended this appointment for Stillington from the outset, for as soon as news of Bishop Bekynton’s death reached him the king granted Stillington custody of the see’s temporalities. It was about four months after the announcement of the Widville ‘marriage’ when this grant was made, on 20 January 1464/5.22

When the king’s proposed choice for the new bishop of Bath and Wells was communicated to the Holy See, however, a difficulty arose. During the lifetime of Thomas Bekynton the pontiff had explicitly reserved to the papacy the nomination of the next bishop of that diocese. Accordingly Pope Paul II now proposed to appoint to this vacant see John Free, a learned English divine resident in Rome.23 When the pope was confronted with the king’s counter-proposal there must have been a small diplomatic crisis. Delicate negotiations doubtless ensued, though no record of them survives.

Meanwhile the bishopric remained vacant in theory, although in point of fact Robert Stillington was already making appointments in the diocese of Bath and Wells, just as though his episcopal elevation had already received papal confirmation.24 The impasse was ultimately resolved by the untimely death of the pope’s candidate, whereupon, Paul II accepted Edward IV’s nominee. On 30 October 1465, by the bull Divina disponente clemencia, the sovereign pontiff at last formally provided Robert Stillington to the vacant bishopric, and the following day, granted faculty for his episcopal consecration.25 Thenceforward Robert Stillington was acknowledged as Bishop-elect of Bath and Wells. The following spring he was finally consecrated by George Neville, the new Archbishop of York.

His subsequent Widville ‘marriage’ was yet another big mistake on Edward’s part, because, like the marriage with Eleanor, it was conducted in secret. In canon law as interpreted in England in the fifteenth century, only a subsequent marriage in facie ecclesiae (i.e. in public) could have had any effect in the face of Edward’s existing contract with Eleanor – and even then only to the extent that the children of the subsequent, public (but still bigamous) marriage could arguably have been regarded as legitimate.26 The church courts would then have contended that Eleanor or her representatives should have objected to the second marriage when the celebrant asked if anyone knew just cause why it should not proceed. Failure to formally object at that stage would have meant that the second marriage, albeit bigamous, would have been capable of producing offspring who could be recognised as legitimate. However, since Edward’s Widville marriage had been secret, neither Eleanor nor anyone else had had any opportunity to object to it. The Widville marriage was therefore invalid and all the offspring of it, bastards.

Although Eleanor did not appeal to the Church courts to uphold her marriage, records of appeals made in other, similar cases do exist. One example is the case of Muriel de Dunham against John Burnoth and Joan, his ‘wife’.27 On Monday 21 June 1288 Muriel appeared before the Consistory Court of Canterbury ‘seeking to have the marriage between John Burnoth of Chartham and Joan, whom he keeps as his wife, annulled and John and Joan separated and John adjudged her husband because, before John made a marriage contract with Joan, he contracted marriage with Muriel by words de presenti’.28 This case took more than six months, and was prolonged by the contumacy of Joan, the allegedly bigamous wife, who refused to appear in court for four months, despite repeated citings to do so. One can imagine that, had Eleanor brought her case to court, Elizabeth Widville might well have proved at least equally contumacious. When judgement had finally been delivered in Muriel’s favour, John and Joan, who were clearly happy living together, appealed against the decision, and although their appeal was eventually quashed and the court pronounced ‘the de facto marriage between John and Joan null and void, and … [adjudged] John to Muriel as her husband and Muriel to John as his lawful wife’,29 it is difficult to believe that John and Joan simply accepted this after fighting so hard against it, or that John and Muriel can have lived together thereafter in contented conjugal bliss, whatever the Church court may have ruled.

Had Eleanor dared to cite the King of England before the ecclesiastical courts, it is equally difficult to believe that Edward would have passively submitted his matrimonial affairs to public scrutiny, or that (if things had ever been allowed to reach the unimaginable stage of judgement being given against him and in Eleanor’s favour) he would simply have accepted this, dutifully parted from Elizabeth Widville and set up home with Eleanor. Had Eleanor even so much as attempted to bring the case to court she may well have been putting her life in jeopardy. Fighting the case in the Church courts was therefore not an option. Eleanor had no realistic alternative but to accept the fait accompli and live quietly in retirement, well away from public life.

While she remained silent, Edward IV apparently treated her with consideration, and showed some regard for her wishes. Nevertheless, Eleanor now seems to have preferred not to continue living alone, on her own manors in Warwickshire. Instead, she apparently preferred East Anglia, and the protection of her sister, the Duchess of Norfolk. Although it was not unusual for a single woman to live in the household of a married relative, Eleanor’s choice may suggest that she felt that her position in the world was now potentially somewhat dangerous. It appears that she felt she would be safer living in a protected environment, with close relatives and their entourage around her. It may therefore be highly significant that this chosen safe environment was undermined by the crown at the very time when the still relatively young Eleanor suddenly died. This point will be examined in greater detail later (see chapters 17 and 18).

One other significant factor helps to explain why Eleanor made no attempt to substantiate her marriage through the courts. Indeed, if we can understand it, this factor will perhaps bring us as close as one can now come to understanding something of Eleanor Talbot’s character. It concerns her religious commitment.