15

MOUNT CARMEL

East Hall, a mile or two to the east of Kenninghall, was a large, moated property, trapezoid in plan, with a bridge across the moat located on the longest, north-western side. Natural springs on the north-eastern side fed both the moat and a series of three fishponds. The enclosure within the moat was of ample dimensions. The longest (north-western) side measured some 444ft in length, while the shortest (south-western) side was about 225ft.1 The dwelling, being defended by a moat, was almost certainly also crenellated, and if it survived today, we should probably be inclined to call it a castle.

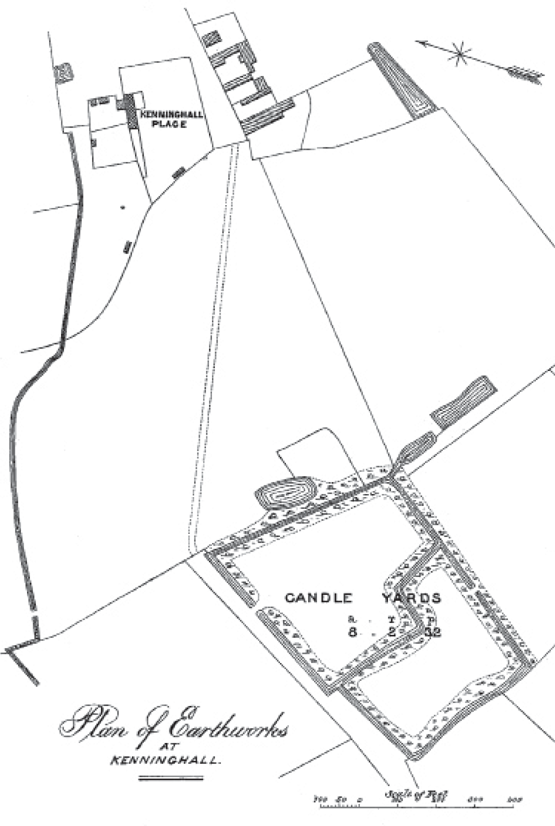

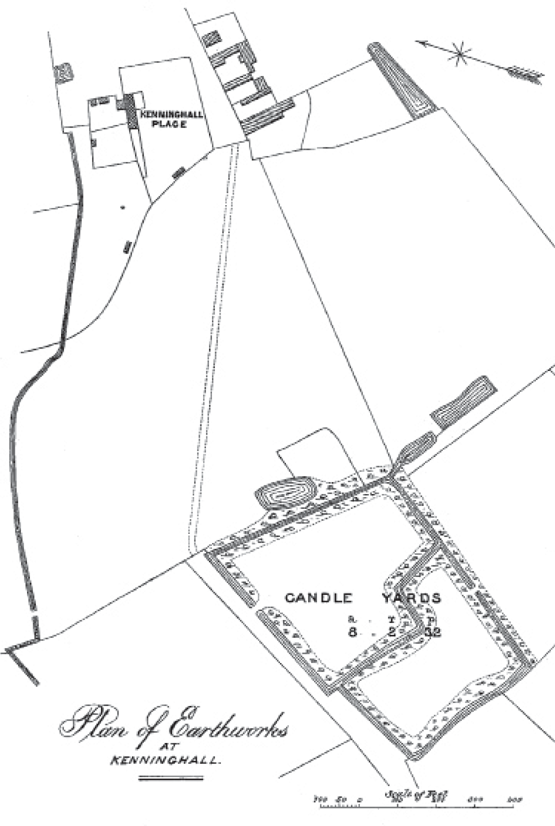

In reality, like the Talbot and Lestrange family home at Blakemere, which Eleanor had known in her childhood, it was actually a fortified manor house rather than a true castle. East Hall, however, was a good deal larger than Blakemere. It was of flint construction, as was common with stone buildings in this part of the country, and the flints that once composed its walls still liberally sprinkle the ground upon its now devastated and empty site. Only the outline of the moat – not so deep today as it once was and filled with bushes and small trees – now defines the site, for the house was destroyed in the sixteenth century, after the third Howard Duke of Norfolk constructed a new residence, Kenninghall Place, a short distance to the east of the old site. East Hall remained the property of Elizabeth Talbot until her death in 1507, although she is not known to have lived there in her final years. The new house, Kenninghall Place, was built and habitable by 1526, so the destruction of East Hall must be dated some time within those nineteen years. Parts of the building may have been left standing for the processing of tallow, for the site became known as ‘the Candleyards’, but by the time of Leland’s visit it was apparently deserted.2

The Kenninghall Estate. Kenninghall Place is the later residence built by the Howard Dukes of Norfolk. ‘Candle Yards’ is the former moated site of East Hall. Originally published in C.R. Manning, ‘Kenninghall’, Original Papers of the Norfolk and Norwich Archaeological Society, Norwich 1870.

East Hall probably dated from the thirteenth century. The first recorded mention of it occurs in 1276, when the manor of Kenninghall was held by the d’Aubigny family. In 1282 both manor and hall had passed by dowry to the Fitzalans. Just over a hundred years later, Richard II confiscated Kenninghall from Richard Fitzalan, Earl of Arundel, and granted it to Thomas Mowbray, first Duke of Norfolk.

When Thomas became the second husband of the Earl of Arundel’s daughter, Elizabeth, he gave her East Hall as her dower house.3 Elizabeth Fitzalan was a long-lived lady. She and her four successive husbands retained Kenninghall until Elizabeth Fitzalan’s death in 1426. The property then reverted to the Montagus. The Nevilles, who inherited the manor, together with the hundred of Guiltcross, two years later, subsequently returned them as a marriage portion to the Fitzalans. This was in 1438, when Joan Neville, a sister of Eleanor Talbot’s uncle, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, married William Fitzalan, ninth Earl of Arundel. In or soon after 1450, William sold Kenninghall back to the Mowbrays as part of the jointure to be settled on Elizabeth Talbot at the time of her marriage to the third Duke of Norfolk’s son and heir.4

Visitors to East Hall in the 1460s would have ridden from the triangular square at the centre of Kenninghall (where the road from Thetford to Norwich passes through the middle of the village) up Church Street, passing the parish church on the left. They would have left the route of the modern road where it bends right towards the village of Fersfield, to continue up what is now a private road. This led to the flint-built outer walls fringing the inner edge of the moat. Crossing the latter by means of what was probably originally a drawbridge, one would have passed through the gatehouse into the large courtyard, containing stables, kennels, garderobes, a kitchen block and the main residential quarters, centred on a great hall with an adjacent solar block that contained more private family rooms and a chapel.

There is clear evidence that Elizabeth Talbot lived at East Hall, for she left her mark on Kenninghall Church, reglazing the east window with Talbot and Mowbray heraldry, surrounding a huge white rose-en-soleil, emblem of the house of York. Some of this glass survived until the 1780s, but all is now gone.5 Elizabeth also rebuilt the church tower which she likewise bedecked with the arms of her own and her husband’s families.6 The remains of her east window were removed early in the nineteenth century, and the shields at the base of her tower are now blank, but high up on its south-western buttress can still be seen a carved Talbot hound, and on the south-eastern buttress is a lion, emblem of both the Talbots and the Mowbrays. Curiously this lion, which should by rights face towards the left, is actually reversed, and faces to the right. This heraldic puzzle is perhaps to be explained by the fact that the lion, high up on the church tower, thus faces across the fields of Kenninghall, gazing towards the moated site of East Hall in the distance.

Elizabeth’s residence at the hall, and her work on the church, probably date from the 1470s and ’80s, when she was a widow. In the 1460s, however, it seems likely that the house was occupied by her sister, Eleanor, who probably also died there.7 During this period of her life, Eleanor’s character was developing in very particular ways, and it is important to attempt to understand what was happening to her. Eleanor’s religious beliefs must have been formed initially in childhood, the germs being inculcated by her mother, Lady Shrewsbury. Her faith was probably never superficial, though there is reason to believe that it grew deeper with the passage of time. All Eleanor’s siblings seemed to have shared a real and lively religious faith. This is evidenced in different ways by the wills of Sir Louis and Sir Humphrey Talbot, and by the lifestyle chosen by the dowager Duchess of Norfolk in her declining years.

Probably for Eleanor (as, much later, for the nineteenth-century Carmelite, St Thérèse of Lisieux) ‘the family into which she was born was deeply imbued with a spirituality of … good works and merit [and] … a standard of behaviour befitting the devout christian was scrupulously adhered to’.8 A picture thus emerges of a girl brought up with a degree of religious commitment that went deeper than the average, and with a clear sense of right and wrong. Eleanor’s father is reputed to have ‘had an inborn sense of justice and fair play’.9

Incidentally, it would, of course, be naïve to imagine that any of this assures freedom from sin, particularly the sins of the flesh. Eleanor’s religious beliefs certainly do not guarantee that she could not possibly have consented to be Edward IV’s mistress. Rather, it is the surviving sources which tell us that she would not consent to this, for they explicitly state that it was Eleanor’s refusal which caused Edward IV to agree to a marriage.

Early in the 1460s, and for reasons that we cannot discern, Eleanor’s religious faith seems to have grown more profound. This may have been either a gradual development, or more in the nature of a coup de foudre. In general terms, this development in a spiritual direction was ultimately shared by her sister, the Duchess of Norfolk, and the principal surviving source stressing Eleanor’s religious motivation is her sister’s indenture of 1495 with Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.10

After her husband’s death, the Duchess of Norfolk chose to further her own spiritual life mainly under the guidance of the Franciscan order and of her friend Anne Montgomery (née Darcy), the cousin by marriage of Sir Thomas Boteler. Together with Anne Montgomery and a small circle of other ladies, the Duchess eventually formed a spiritual community associated with the prestigious Abbey of the Poor Clares (‘the Minories’) at Aldgate.11 Eleanor, on the other hand, seems to have elected to pursue her religious development under Carmelite guidance. Evidence for this is supplied by Eleanor’s seals, by the possible negotiations conducted on her behalf with the Whitefriars and by her eventual burial at the Norwich Carmel. In the case of the Duchess of Norfolk, her degree of spiritual commitment was ultimately to be profound, and there is no reason to doubt that this was also true in the case of Eleanor. It will scarcely be possible, therefore, to understand the person Eleanor was to become in the last five years of her life, without taking account of this development.

As we have seen, when she was married to Thomas Boteler, Eleanor had sealed her documents using a signet ring possibly given to her by her mother. The bezel of this ring bore the impression of a daisy, the Countess of Shrewsbury’s name-flower.12 Later, as a widow, Eleanor acquired new signets. One of these (plate 26) was a ring with a bezel which appears to depict some kind of elongated trapezium, somewhat irregularly shaped, and wider towards the top.13 This design is at first sight rather difficult to interpret. It appears to represent a piece of cloth. On the lower part of the bezel a rectangular area is clearly marked with a criss-cross design indicating woven fabric. A larger, bunched shape towards the top of the design, while somewhat worn in the surviving seal impression, appears to bear the same criss-cross pattern. In the centre (between the two areas representing fabric) there is a pointed oval shape, resembling an eye or a mouth. It seems that what is intended is a representation of the Carmelite brown scapular.

This comprises part of the religious habit of Carmelite friars and nuns, for whom it takes the form of a long, rectangular piece of cloth, with a hole in the middle through which the head and neck pass (see below). For the friars and nuns the two lengths of fabric hang down over the wearer’s chest and back, reaching below the knees. Lay members of the Carmelite order also wear either a form or a representation of the scapular, but for them this item is usually much smaller (see plate 27). The scapular comprises a special token of the Carmelite order, which is believed to have been delivered by the Blessed Virgin (Our Lady of Mount Carmel) to the Carmelite saint, Simon Stock, in a vision.

A full-sized scapular, as worn by a Carmelite friar or nun.

St Simon Stock receiving the scapular from the Blessed Virgin Mary.

When Pope Nicholas V established the second and third orders (Carmelite nuns and tertiaries) he extended to them the wearing of the brown scapular. Thus, as a lay member of the order (tertiary), Eleanor would have been required to wear the scapular, even if only in a symbolic form. Wearing a representation of it on the bezel of her signet ring would have been one means of fulfilling this obligation.

On Eleanor’s seal impression the lower, rectangular, area of fabric represents that portion of the garment which hangs down in front, over the wearer’s chest, while the larger bunched portion towards the top of the design is the part of the garment which covers the wearer’s back. The eye-shaped gap in the centre would be the hole to accommodate the wearer’s head and neck. It seems indicative of Eleanor’s devotion that she should have chosen to have this simple garment depicted on one of her seal rings.

Eleanor also had a further seal ring (see plate 24). Only one impression of this appears to survive, and it is imperfect, for the signet ring was evidently dragged slightly to the right as it was extracted from the wax, thus blurring the impression, which now appears somewhat oval in shape.14 The matrix was, nevertheless, probably circular, or nearly so. It depicted the bust of a woman, veiled, and facing three-quarters right. This represents the Virgin Mary, holding the Christ child on her left arm (though the child’s image is very blurred). In fact this signet appears specifically to depict the ancient icon of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, brought from the Holy Land when the Carmelite hermits fled before the tide of Islam and now preserved at the church of San Niccolò al Carmine, Siena (see plate 25).

The meagre surviving documentary evidence suggests that it was probably in March 1462/3 that Eleanor became a tertiary, associated with the Carmelite Priory in Norwich, her commitment to the Carmel being apparently negotiated on her behalf by her brother-in-law the Duke of Norfolk, through the intermediary of his cousin Sir John Howard.15 As a key member of the Mowbray affinity, there is no doubt that John Howard was well acquainted with members of the Talbot family. Elizabeth Talbot, Duchess of Norfolk, is mentioned on several occasions in Howard’s surviving accounts.16 He lent money to her, bought and sold horses and wine on her behalf, and had the loan of her minstrels. Later he was associated with her in projects such as the rebuilding of Long Melford church in Suffolk. Howard also knew Elizabeth’s only surviving brother Sir Humphrey Talbot and her nephew Thomas Talbot, Viscount Lisle, to both of whom, in May 1465, he delivered gifts from the Duke of Norfolk in the form of valuable crimson cloth, the livery colour of the Mowbray dukes.17

Given these contacts, it is not surprising that Sir John Howard should also have had connections with the Duchess of Norfolk’s sister, Eleanor, particularly since the latter seems to have become resident in East Anglia. Howard may indeed have known a very great deal about Eleanor’s affairs. We have seen already that he was Edward IV’s host in Suffolk, when the latter was still Earl of March, in the summer of 1460, and that he may have been Dr John Botwright’s correspondent in the matter of Eleanor’s patronage of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.18

On 23 March 1462/3, Howard paid Thomas Yonge, sergeant at law, 13s 4d ‘for his two days labour at the White Friars for my lord’s matter’.19 The editor of the Howard accounts assumed that this was a reference to the Carmelite Priory in London. But there is no justification in the text for such an assumption. Although both Howard and the Duke of Norfolk seem to have been in London at about this time, there is nothing to indicate where the lawyer, Thomas Yonge, had been, while carrying out his errand. Thus his messages could equally well have been delivered to the Norwich Carmel.

Whichever Carmelite priory was Yonge’s destination, it seems likely that the business that Howard was conducting with the Whitefriars on the Duke and Duchess of Norfolk’s behalf was connected with Eleanor’s oblation. A few months later, in July 1463, Sir John Howard was again acting as an intermediary for the Duke of Norfolk. On this occasion he paid John Davy 16d ‘to ride on my lord’s errand to Kenehale [Kenninghall]’.20 While the Whitefriars’ errand may or may not have been to the priory in Norwich, in this case there is no doubt regarding the destination of the messenger. Given Eleanor’s probable residence at Kenninghall at this time, it is not fanciful to suggest that the Duke of Norfolk’s message on this occasion was addressed to his sister-in-law, and may once again have been connected with the ongoing negotiations in respect of Eleanor’s oblation to the Carmelites.

Eleanor’s involvement with the Carmelite order may have arisen in some way out of her residence at East Hall, for the village of Kenninghall had apparently already produced two noted Carmelites, the late John Kenyngale, former chaplain to Edward IV’s parents, prior of the Whitefriars in Norwich and Father Provincial of the Carmelite order in England until his death in 1451, and Peter Keningall, prior of the Carmelite Priory in Oxford and noted preacher.21 This suggests that a Carmelite presence had already, in some way, made itself felt in Kenninghall before Eleanor arrived there. It is also possible that Eleanor had met Prior Peter before she came to East Anglia, either during her own residence in Warwickshire, or through her stepmother-in-law, the second Lady Sudeley, whose previous home at Minster Lovell Hall was not far from Oxford.

The Master of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, Eleanor’s friend and protégé Dr Thomas Cosyn, would later describe her as Deo devota (‘vowed to God’).22 Nevertheless, Eleanor never ‘entered religion’ in the sense of becoming a nun. It is essential to state this unequivocally because there has been a widespread popular misconception on the subject, which seems to have become particularly firmly embedded in historical novels. However, ‘the number of laywomen living a life of religious devotion and piety in the later Middle Ages blurred the distinction between the lay and religious worlds’,23 and there were various alternative options available to fifteenth-century English women who wished to be ‘vowed to God’. The term ‘vowess’ which became established in the late fifteenth century, describes the vocation of laywomen – often (though not invariably) widows – who adopted a way of life that contained elements of both the religious and the lay state. For such women, says Erler:

the significant vow was one of perpetual chastity. Like nuns, vowesses were clothed and veiled at an episcopal ceremony; unlike nuns, these women did not promise either poverty or obedience. Indeed their state remained formally a lay one, with physical freedom to come and go, and economic freedom to dispose what were sometimes considerable holdings of land or goods. The vow did not imply a rule of life, like that of a third order, and no particular spiritual regimen was specified.24

There was an established ceremony for becoming a vowess, which is preserved in several pontificals. The ceremony took place before the reading of the gospel at mass. The vow was made to the local bishop, who presided from his throne or chair, received the written vow and blessed, clothed and veiled the woman, giving her a ring. The making of the vow was recorded in his episcopal register.25 The motivation of vowesses was varied, and not always exclusively religious. Some vowesses made their vows in obedience to the terms of their late husbands’ wills, and in many cases economics and social and legal status seem to have been significant factors in their decision-making process. In the case of Eleanor’s religious oblation, however, religious motives seem to have been a serious consideration. Both the words of her friend, Cosyn, and the design of her seals imply a serious religious commitment.

But Eleanor did not become a vowess. The episcopal register of Bishop Walter Lyhart of Norwich is unpublished. The original, which is in a rather decrepit state, is not easy of access, and the available microfilm version is of poor quality and difficult to read for some folios. However, an examination of both the microfilm and the original register has revealed no record of Eleanor’s profession as a vowess before Bishop Lyhart,26 though the bishop, a Lancastrian by inclination,27 would doubtless have been intrigued by Eleanor’s story had she chosen to reveal it to him.

As we have already seen, there is evidence that suggests that Eleanor’s association was specifically with the Carmelite order. This makes it certain that she remained a laywoman, because there were no nuns of the Carmelite order in England in the fifteenth century. The Carmelites did, however, have an established third order. That fact, together with the evidence of Eleanor’s seals, and the possible evidence of negotiations undertaken with the Whitefriars on her behalf suggests that Eleanor became not a vowess but a Carmelite tertiary. Her profession as a tertiary would have been recorded not in the episcopal register but in the records of the Norwich Carmel, which are not extant. It would have been made to Prior Richard Water, the superior of the Norwich house,28 or possibly (if he were on hand) to the provincial of the Carmelite order in England.

The only reference to the Norwich Carmel in Bishop Lyhart’s register for the 1460s appears to be a record of the appointment of ‘Andrew Fysshman of the order of Carmelite friars of Norwich’ to the living of Beston juxta Norwich as vicar, in February 1461/2.29 But while the appointment of a Carmelite friar to a living within his diocese was a matter for the Bishop, in respect of its internal affairs a religious order would certainly have kept its own records, and the profession of a tertiary would have fallen within this category.

As Erler has stated (above), joining a third order was distinct in certain essentials from the way of life adopted by most vowesses. Being a tertiary implied both a rule of life and religious obedience. As a tertiary, Eleanor would have been committed to the recitation of the Divine Office according to the Carmelite usage. Following an earlier Carmelite tradition which is examined in more detail below, it is possible that she may also have volunteered (or been required) to dwell in a fixed abode agreed with the prior to whom she had made her oblation.

The Carmelite order had been founded in the twelfth century in the Holy Land, when, in the wake of the Crusades, a group of Christian hermits settled on Mount Carmel, near the ‘fountain of Elijah’. These men (and at that period the members of the order were all males) sought to live as contemplatives. When Moslem victories forced them to leave, they settled in western Europe, establishing convents, but the aspiration towards the contemplative life remained.30

Until the fifteenth century there were no Carmelite nuns. Women could, nevertheless, be associated with the order in several ways, all without ceasing to be members of the laity. The details of such a connection prior to the fifteenth century are somewhat complex, but there were basically three possible levels of association: as a benefactress (or confraternity member), as an oblate (or manumissa31) and as a conversa. A benefactress supported the order financially, and in return received ‘letters of affiliation’, but she took no vows of any kind. An oblate (manumissa) took a vow of poverty, chastity and obedience, but no specific vows to the rule of the order. A conversa took solemn vows to the prior of the Carmelite house where she made her oblation, and became subject to the religious vow of stabilitas: residence in a fixed abode, assigned to her by the prior.32 In other words ‘the degree of affiliation varied. Conversæ consecrated themselves to God through the three Vows, like the friars themselves. Oblates (manumissae) also took at least one of the Vows. Confraternity members participated in the spiritual benefits of the Order and in exchange conferred some material benefice on the Order.’33 Conversæ were usually unmarried women or widows, but they could be married. In May 1343, for example, in Florence, Salvino degli Armati and his wife Bartolomea simultaneously became oblates of the Carmelite order, he as a converso, she as a conversa.34

However, the 1460s – the time at which Eleanor formally associated herself with the Carmelites – marked a period of transition for the order. In October 1452 Pope Nicholas V (who, a year or so earlier, had received Eleanor’s father during his visit to Rome) issued the bull Cum nulla, establishing the second and third orders of the Carmelites. The ‘first order’, of course, comprised the friars. The new ‘second order’ was for Carmelite nuns, while the ‘third order’ (members of which are called ‘tertiaries’) represented a formalised system of association for those lay people who wished to join the Carmelites without giving up their lay status.

The changes introduced by Pope Nicholas filtered their way across Europe gradually over the next fifty years or so. As a result, it is difficult to know precisely under what circumstances Eleanor formed her association with the Carmelites. What is beyond question, however, is that in the fifteenth century there were no Carmelite nuns in England, for the second order did not reach this country before Henry VIII’s break with Rome.35 In fact, it appears that the second order spread somewhat slowly in Europe as a whole. Thus, while the Carmelite monastery of the Incarnation at Avila in Spain (where the future St Teresa would assume the habit of a Carmelite nun in 1536) had been founded as early as 1479, its foundation was initially ‘as a hospice for pious ladies who wished to live as Carmelites’. It only formally became a monastery of the second order in 1515 (the year of St Teresa’s birth).36

The implementation of the new rule for lay oblates may also have proceeded rather slowly. Thus, while it is to be presumed that in general terms Eleanor became a member of the third order as established by Nicholas V – and her apparent use of the scapular implies this – nevertheless, her association with the Carmelites may have retained features of the earlier system. It is possible, for example, that she started out as a benefactress or confraternity member. But Dr Cosyn’s characterisation of his friend and patroness as Deo devota clearly implies that she progressed beyond this level, and took vows of some kind. There are also indications that the rule of stabilitas, which had applied to Carmelite conversae, may have influenced her subsequent way of life, since she seems to have fixed her place of residence in the vicinity of Norwich – probably at Kenninghall. Profession as a tertiary was and is open to married people. Eleanor’s association with the Carmelites would, therefore, have been entirely compatible with the married state. Indeed, the fact that she chose this specific kind of religious life rather than opting to enter the monastery or convent of some other order could perhaps be seen as implicit evidence that she was not able to become a nun because she had a living husband.37

In its origin (and also as later reformed, in the sixteenth century, by St Teresa of Avila and St John of the Cross) the ethos of the Carmelite order comprises a contemplative and mystical element. It is difficult to know precisely to what extent this aspect of the order may have impinged upon Eleanor, but while the Middle Ages saw this element of the Carmelite way often subverted and submerged, it was never entirely lost to sight, and successive priors-general repeatedly attempted ‘to restore something of its original spirit to the order’.38

Probably Eleanor’s interest in the Carmelites arose initially as a response to their long-standing tradition of devotion to the Blessed Virgin. ‘This promise of the special protection of Mary, together with the indulgences associated with the wearing of the scapular, would [probably] have outweighed any other motives for electing to become associated with [the Carmelites].’39 At the same time, however, contemplative Christianity undoubtedly flourished in late medieval England. ‘Women saints and mystics proliferated in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries … [and] on the whole [they] did not come from the lower orders of society.’40

Richard Rolle, Walter Hilton, the anonymous author of The Cloud of Unknowing and Julian of Norwich all lived and wrote in England in the late fourteenth century. Their works of spiritual guidance may have been accessible to Eleanor. The author of The Cloud, who may well have been a friar (possibly even a Carmelite), gave the following advice to those seeking to follow the path of contemplation – words which Eleanor might have read:

Go on, I beg you, with all speed. Look forward, not backward. See what you still lack, not what you have already; for that is the quickest way of getting and keeping humility. Your whole life must now be one of longing, if you are to achieve perfection. And this longing must be in the depths of your will, put there by God with your consent. But a word of warning: he is a jealous lover, and will brook no rival; he will not work in your will if he has not sole charge; he does not ask for help, he asks for you.41

Whether or not readers can share, or even understand, such aspirations is of little importance. What matters is that at a certain point, probably in 1463, Eleanor Talbot committed herself to association with the Carmelite order. Eleanor’s spiritual development probably subsequently led her in a contemplative direction, with the implicit call to renounce ambition and focus exclusively on her relationship with God. In the words of a modern Carmelite writer, such a vocation would have involved ‘accepting her nothingness and making no fuss about it’.42 Obviously anyone who chose to base their life upon such foundations will have taken no interest whatsoever in the thought of lengthy court proceedings aimed at establishing social status. ‘Women mystics saw their way to the imitation of Christ through renunciation’, and suffering was viewed as an integral part of the process.43 Eleanor’s total lack of interest in seeking recognition that she, rather than Elizabeth Widville, was the real wife of the king, thus becomes entirely and totally comprehensible. Moreover, it is very difficult to imagine how a person with such aspirations could possibly have anything in common with an indolent, sensual and selfish hedonist like Edward IV.

Since she did not become a nun, but a lay associate, Eleanor would not have been required to wear a formal religious habit. However, other women of the period who became closely associated with religion (including Cecily Neville, Duchess of York, and her cousin, Margaret Beaufort, Countess of Richmond and Derby) did adopt a form of dress that resembled a nun’s habit.

It is therefore potentially significant that the Coventry tapestry of about 1500, which depicts various fifteenth-century courtiers, includes amongst the women, two female figures in quasi-religious dress. The two women in question stand just behind two other female figures who have been identified as Margaret Beauchamp, Countess of Shrewsbury, and her half-sister, Anne Beauchamp, Countess of Warwick. The figure identified as Margaret Beauchamp, though dressed in costume of a later period, does resemble other surviving images of the Countess of Shrewsbury. The two figures in quasi-religious dress who stand behind the Beauchamp half-sisters could therefore represent Margaret’s daughters, Eleanor and Elizabeth, who respectively associated themselves with the Carmelite and the Franciscan orders. But of course, the identity of the possible Eleanor image on the Coventry tapestry – like the identity of other figures represented there – is not absolutely certain. Nor can the image necessarily be regarded as an authentic ‘portrait’.

Margaret Beauchamp, Countess of Shrewsbury;

A figure which may represent Eleanor Talbot, redrawn from the Coventry Tapestry (c.1500).