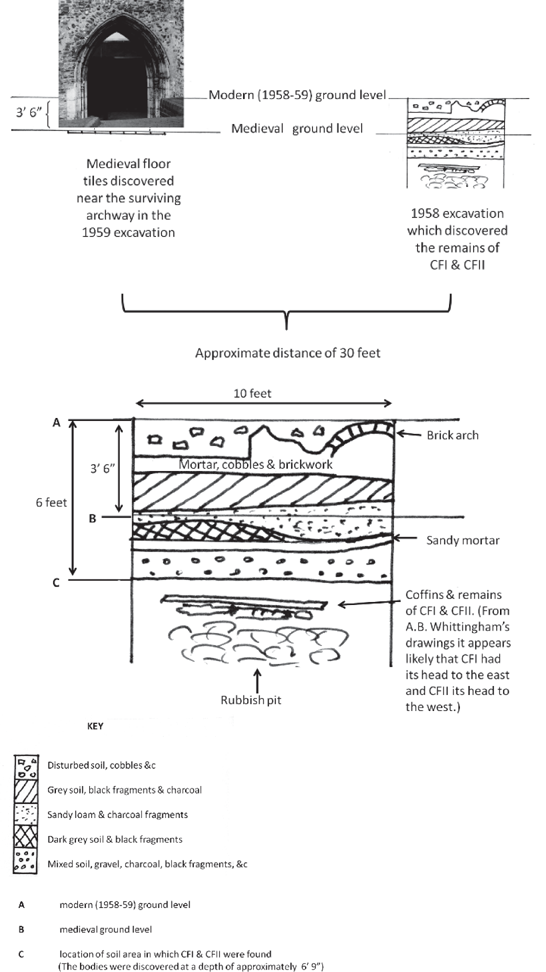

Plan of the 1958 and 1959 excavations of the Whitefriars’ site in Norwich, redrawn by the present author from A.B. Whittingham’s surviving excavation notes on 21 August 1998.

We left Eleanor Talbot’s body reposing in a tomb within the priory church of the Norwich Carmel, where it was laid to rest by her sister in the summer of 1468. What subsequently became of Eleanor’s tomb, and the physical remains which it contained? Of course, English burials in the churches of religious orders found themselves at something of a disadvantage in the sixteenth century, when Henry VIII’s so-called ‘Dissolution of the Monasteries’ robbed them of their home. In the celebrated case of Richard III, lurid tales were later recounted of his body being cast out of its tomb and mistreated as a result of the Dissolution. But, as the present writer argued in 2004,1 and as everyone now knows, this story was mere sensationalism, and definitely a later invention.

The truth is that modern excavations on the sites of religious houses normally find intact burials preserved under the ground, even though their tomb superstructures may have vanished. Eleanor’s resting place was apparently still identifiable amongst the ruins of the Carmelite priory when Weever passed that way in the early seventeenth century, eighty years or more after the Dissolution. It is therefore reasonable to suppose that her body remained in its original burial place for at least a hundred years following the Dissolution, and probably remained at the Whitefriars’ until recent times. One possibility, of course, is that it could still be there.

In 1958, however, a rescue excavation took place on the former Carmelite priory site in Norwich, ahead of further development by Jarrolds, the property owners. Unfortunately this excavation was never properly published by the archaeologists, and the only surviving contemporary accounts of it seem to be a newspaper report in the Eastern Daily Press, and two short reports in Jarrolds’ own in-house magazine.2 Moreover, the formal site notes and plans of the excavation appear to be no longer extant. Nevertheless, after much searching the present author was able to find the original private notebooks of the excavator in the Record Office in Norwich. These include sketches and plans, but no dimensions.

The excavation was located towards the southern boundary of the priory precinct, near the River Wensum and Whitefriars Bridge. About thirty feet to the east of the surviving arch of an anchorite’s cell the excavators found what appeared to be a rubbish dump, filling a pit. In a level which contained broken pottery of the seventeenth century, two human skeletons were found, approximately 6ft 9in beneath the then existing ground level. One of the bodies was judged to be male and the other female, but no detailed study of the remains was undertaken at that time. The remains which were adjudged to be female lay in the remains of a medieval oak coffin (see plate 31). Fragments of medieval stonework were also found. The implication would appear to be that the bodies had been thrown into a rubbish dump at about the middle of the seventeenth century (around the time of the Civil War). The rubbish dump had been a hole in the ground. The find location was clearly not the original place of burial, so the bodies had presumably originally been buried elsewhere on the priory site.

The female skeleton, identified as Carmelite Friary Inhumation II (or CFII), was placed on exhibition at St Peter Hungate Church Museum in Norwich, lying in its restored wooden coffin. The coffin and bones were displayed upon a much later wooden bier which had no connection with either of them. It was because the skeleton was on display at that museum that it was first seen by the present writer, who noted with interest that the remains were said to belong to a medieval female and to come from the site of the Carmelite priory. The skeleton remained on display at St Peter Hungate Church Museum until 1996, when it was removed from exhibition and taken into storage at the Castle Museum in Norwich. Subsequently the remains have been placed on display at Norwich Castle. Attempts on the part of the author to locate the other (possibly male) remains (CFI), and the associated finds of stonework have so far been unsuccessful. These seem to have vanished. They may in fact still be somewhere in the Norwich Castle Museum store, but they are not catalogued or recorded. However, in 1996 the Director of the Norfolk Museums Service kindly agreed to an examination of CFII by Mr W.J. White (the late curator of the Centre for Human Bioarchaeology, Museum of London).

Plan of the 1958 and 1959 excavations of the Whitefriars’ site in Norwich, redrawn by the present author from A.B. Whittingham’s surviving excavation notes on 21 August 1998.

Following his examination, Mr White reported his findings to the Norfolk Museums Service (30 September 1996) as follows:

The bones of the lower leg were damaged therefore the maximum length of the femur was used in the formula for the estimation of height during life.3 This person would have stood 169 cm (5’6”) tall … The skull was sufficiently preserved for the conventional measurements to be made. The calculated cranial index was 81.2, ie within the brachycephalic or ‘short-headed’ range.4 … The skeleton examined was of a sturdily-built woman aged between 25 and 35, who, appears to have enjoyed generally good health from at least late childhood until her early death and who almost certainly had never experienced childbirth … The above data, including non-parous state and age 25–35 are not inconsistent with what is known of Lady Eleanor Butler [sic] … The Norwich skeleton did share one trait with John Talbot, namely brachycephaly, his cranial index being calculated as 92.0. However, this trait was shared with the majority of the population of medieval England.

An additional comparison might be made between the height of CFII and that of the first Earl of Shrewsbury, for the Earl was 5ft 8½in (174.5 cm) tall,5 based upon Egerton’s measurement of his femur as 18.5in in length.6 Mr White also noted that there were indications, particularly from the state of the teeth (which suggested a refined diet containing sugar) that the individual was a member of the nobility. In this case the dental evidence might further suggest that the age at death was towards the upper limit of the range established. In 1996, when Mr White wrote his report, it was still considered possible to assess whether (and how many times) a woman had borne children, based upon an examination of the pelvic bones, but sadly such assessments are now considered unreliable.7

In addition to Eleanor Talbot, Weever, whose account was published in 1631, listed eighteen other females and twenty-two males as having been interred in the church of the Carmelite Friary, Norwich, excluding the Carmelite religious themselves, whom he lists separately, and only one of whom was female: an anchoress. The list of female burials (to which the Carmelite anchoress has been added) is as follows:

1. Lady La… Argentein

2. Lady Eleanor Boteler [Talbot]

3. Lady Alice Boyland

4. Lady Katherine, wife of Sir Bartholomew Somerton, Kt.

5. Lady Alice, wife of Sir Will. Crongthorp

6. Lady Joan, wife of Sir Thomas Morley

7. Marg. Pulham

8. Lady Elizabeth Hetersete

9. Lady Katherin, wife of Sir Nich. Borne

10. Joan, wife of John Fastolph

11. Alice, wife of Thomas Crunthorp

12. Lady Alice Everard, died 1321

13. Lady Alice With, died 1561

14. Lady Elizabeth, third wife of Sir Thomas Gerbrigge (who died 1430), formerly wife of Sir John Berry and daughter of Robert Wachesham, died 1402.

15. Lady Alice, wife of Sir Edmund Berry (who died 1433) and daughter of Thomas Gerbrigge

16 Elizabeth, first wife of William Calthorp and daughter of Sir Reignold, Lord Hastings, Waysford and Ruthin, died 1437

17. Cecily, child of William Calthorp

18. Lady Margery, wife of Sir John Paston and daughter of Thomas Brews, died 1495

19. Lady Margaret, wife of Sir Thomas Pigott, died 1489

20. Emma (Stapleton) Carmelite anchoress, died 2 December 1422.

Weever was writing nearly a hundred years after the Dissolution, and the source for his list is not known but the eastern end of the Carmelite Church is thought to have been still standing (in ruins) in the mid-seventeenth century. Indeed, although the main church building had been demolished by the eighteenth century, part of the Holy Cross chapel was still intact and in use as a Baptist chapel as late as 1883.8 Thus Weever himself may well have seen the tombs he lists. At all events their existence would appear to have been within living memory in 1631. Where his list can be checked by reference to other source material it proves to be accurate.9

In addition to Weever’s list, wills indicate that six further female burials also took place at the Carmelite church, as follows:

21. Christian Savage, widow of Peter Savage of Norwich, died 1440

22. Margaret Furbisher, widow, died 1466

23. Christian Boxworth, widow, died circa 1500

24. Elizabeth, widow of Will. Aslake, died 1502/3

25. Margaret Beaumond, died 1523

26. … Hevyngham, mother of John Hevyngham, parson of Kesgrave, died circa 1500.10

Probably, however, all of these can be eliminated as candidates for identification with CFII on the grounds of their social status. This would leave a total of twenty possible candidates who might possibly be CFII.

For the female interments listed by Weever, the following additional information has been discovered:

1. Lady La… Argentein: first name Laura; sister of Robert de Vere, Earl of Oxford; wife of Sir Reginald Argentein, and probably the mother of his son, John. She was the daughter of Hugh de Vere, Earl of Oxford and his wife, Hawise de Quincy, who were married in about 1223. Laura was born at Hedingham Castle, circa 1230, and died in 1292 in her early 60s.11 Her age at death shows that she cannot be CFII.

2. Lady Eleanor is the subject of this book.

3. Lady Alice Boyland: wife of Roger de Boyland, who died before 1256. Their son, Richard de Boyland, was a successful lawyer and was appointed to the bench in 1279. He was still living in 1298. Lady Alice must have died after 1256 (when the Norwich Carmel was founded), but her date of death is unknown.12

4. Katherine Somerton’s husband, Sir Bartholomew Somerton, was related by marriage to the Pastons, and possibly also to Friar John Somerton (fl. 1479) who may have been a Carmelite though he is not listed as such by Weever. Bartholomew had at least two children, Thomas and Constantia, but the name of their mother is not stated.13

5. Lady Alice Crongthorp is identified by Weever as the wife of Sir William Crongthorp. Two individuals of this name are known, in connection with the manor of Crownthorpe, near Wymondham: Sir William Crongthorp II (fl. c. 1346) and his father (fl. c. 1280–1320). Both had at least one son called William, but the name of the mother is in neither case recorded. Sir William Crongthorp I was almost certainly Alice’s husband, however, as Weever lists among the Carmelite Friars also buried at the friary in Norwich Friar William Crongthorp, who had been a knight before he became a friar, and who had died on 12 April 1332. This suggests that his wife had predeceased him and he buried her at the friary, perhaps in about 1330, before himself entering the Carmelite order. Moreover, William II is known to have had a wife called Katherine.14

6. Joan Morley’s husband, Thomas, utimately had a higher rank than Weever allows him, for in 1379 he became the fourth Baron Morley. Joan, however, probably died shortly before this, since her husband remarried in about 1380. Joan’s age at death is not recorded. However, her husband was born in about 1354, and she is unlikely to have been older than he was, so she was almost certainly under 25 at the time of her death. She is therefore unlikely to be CFII. Joan had at least one son, Robert.15

7. Marg Pulham is perhaps to be identified with the unnamed first or second wife of Sir Thomas Pulham of Stradbroke, Suffolk, (who died 1532), who left 10s to the Norwich Carmelites in his will. She was possibly also the mother of his daughter, Margery. The family may have been related to the Carmelite Friar, Robert Pulham, who Weever also lists as being buried at the Whitefriars.16

8. Elizabeth Hetersete can be identified with Elizabeth, wife of Sir John Hethersett, by whom she had a son, William. Sir John died circa 1355, but Elizabeth survived him and remarried. She probably died in about 1376. Since she must have been at least 16 when her first husband died (or she could not have borne him a son) she seems almost certain to have been more than thirty-five years old at the time of her death, and is therefore unlikely to be CFII.17

9. Katherin Borne is perhaps to be identified with the unnamed mother of Elizabeth Borne, wife of John Harling.18

10. Joan Fastolph cannot, at present, be identified and no further details about her are available.

11. Alice Crunthorp, wife of Thomas Crunthorp, is fairly certainly the unnamed wife of Thomas Crungethorpe (died c. 1400). It is not known whether this couple had children.19

12. Alice Everard was the wife of Sir Thomas Everard, who was alive as early as the reign of Henry III. She may not have been his first wife, and must have been considerably younger than her husband, but even so, she would have been an old lady by the time of her death in 1321. She is known to have had at least one son, Thomas.20 Her age at death means she cannot have been CFII.

13. Lady Alice Withe is said by Weever to have been buried at the Norwich Carmel in 1561. This is certainly an error for 1361. No burials could have taken place at the priory after the Dissolution. Blomefield gives Lady Alice as the wife of Sir Oliver Wythe, who was also buried at the Norwich Carmel, as were other members of his family. Oliver and Alice are thought to have been the parents of Sir John Wyth (died 1387).21 Alice was therefore probably too old at death to be CFII.

14. Elizabeth Gerbrigge was the mother of no.5, Alice Berry. She was probably about 47 when she died. Thus she cannot be CFII.

15. Alice Berry was the mother of Agnes, wife, of Judge William Paston. She died at about the age of 50.22 Thus she cannot be CFII.

16. Elizabeth Calthorp was the wife of Sir William Calthorp II. Although Weever describes her father as Lord Hastings, this title was, in fact, disputed, but Reynold did hold the title Lord Grey, which Weever omits. Elizabeth was about 30 at the time of her death, and had at least three children, John, Anne and William.23 Based on her age at death she could be CFII.

17. Cecily probably died about 1390. She was probably the daughter of William Calthorp I (c. 1360–1420) by his first wife, Eleanor Mawtby. Weever states that she was a child at the time of her death.24 She therefore could not be CFII.

18. Margery Paston is well known from published editions of the Paston family papers. She was aged about 35 at the time of her death, in 1495, and had had at least six children: Christopher, Sir William, Dorothy, Elizabeth, Philippa and Philip.25 On the basis of her age at death, however, she could be CFII.

19. Margaret Piggott may be the Margaret who was wife to Jeffrey Pigot, fl. c. 1457/8. No other details are known.26

20. Emma, the Carmelite anchoress, was the daughter of Sir Miles Stapleton. Unfortunately more than one individual is known to have borne the name Miles in different generations of the Stapleton family, and it is not clear which one was Emma’s father, which makes it difficult to estimate her age at death. One would expect her to have been childless, since she does not seem to have been married before she became an anchoress. Living, as she did, a life of asceticism, it may be considered doubtful whether, if she died in her early thirties, she would by then have consumed sufficient sugar to display the incipient caries found in CFII, or whether she would have been buried in an oak coffin. She cannot, however, be ruled out of consideration.

By excluding numbers 1,6,8,12,13,14,15 and 17 from Weever’s list, the evidence of age at death reduces the list of candidates for identification with CFll from twenty to twelve. Clearly, this is insufficient for a positive identification of the remains. As Mr W.J. White indicated in his report to the Norfolk Museums Service, this could perhaps be achieved by mitochondrial DNA analysis, which would, however, require the identification of a control sequence of DNA from a female-line relative of Eleanor. No such sequence has as yet been identified. Carbon dating and strontium 90 analysis of the enamel of the teeth to determine geographical origin might also be helpful, and the author is at present seeking to explore those potential ways forward. Meanwhile, although its identity is certainly not definitely established, the possibility remains that the skeleton preserved in Norwich could be that of Eleanor Talbot.

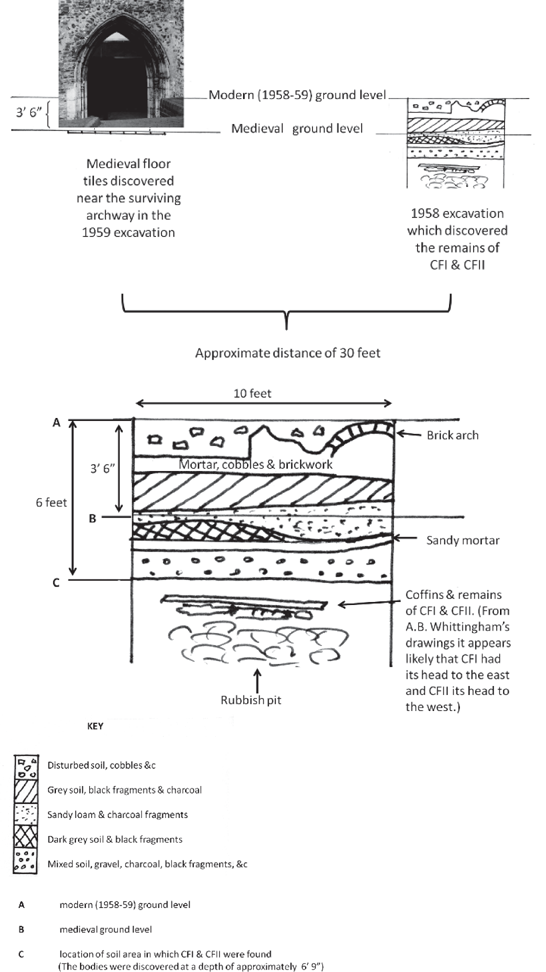

Kuckle joints of the human hand.

There are two futher kinds of evidence which might conceivably have strengthened the evidence for the possible identification of the CFII remains with Eleanor. These concern ‘the Talbot fingers’ and the congenital absence of certain teeth in fifteenth-century members of the Talbot family.27

The anomaly known as ‘the Talbot fingers’ is more properly called symphalangism. It is popularly known as ‘stiff fingers’. It is the condition of ‘hereditary absence of one or more proximal interphalangeal joints’.28 That is to say, the central knuckle joints (see illustration), which in a normal hand allow the fingers to bend, are fused in cases of symphalangism, so that normal movement is not possible, hence the term ‘stiff fingers’. This condition reportedly exists in some members of the Talbot family at the present day, and is traceable in that family back to at least the eighteenth century. The further claim had been advanced that the condition had also been present in the skeleton of the first Earl of Shrewsbury (died 1453), who was Eleanor’s father. If this claim were well founded, the question would have arisen whether Eleanor might not also have suffered from this congenital condition, in which case one might have expected evidence of it in the Norwich skeleton, CFII.

In the event, however, symphalangism proved not to be helpful in identifying CFII. When the Norwich skeleton was ejected from its tomb, probably in the mid-seventeenth century, it seems likely that its coffin was overturned. One report of the discovery of CFII, in 1958, speaks of a coffin being found crushed on top of one of the sets of bones.29 Probably as a result of such treatment, the skeleton, while substantially intact, is lacking some small bones, including most of the bones of the fingers and toes, where the evidence of symphalangism, if it existed, would have been found. More importantly, however, the contention that symphalangism existed in the Talbot family as long ago as the fifteenth century has been questioned. The transmission of such a congenital abnormality through fourteen generations of a family would be unusual. There is, in fact, nothing in the medical report which was drawn up in the last century when the remains of the first Earl of Shrewsbury were examined, which would substantiate the claim that his bones showed any evidence of this anomaly,30 and the most recent re-examination of the case of John Talbot concluded that ‘adequate proof … is lacking’.31

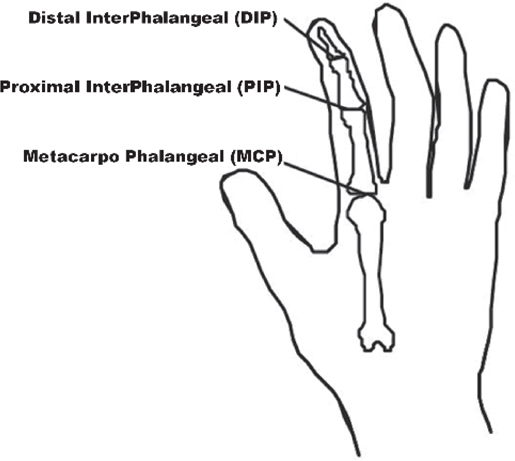

Of greater interest is the phenomenon of congenitally missing teeth, because the existence of this anomaly can certainly be substantiated in at least one close relative of Eleanor Talbot. Lady Anne Mowbray, Duchess of York and Norfolk, who died in 1481, a little short of her 9th birthday, was Eleanor’s niece, the daughter of her younger sister, Elizabeth Talbot, Duchess of Norfolk. Anne’s body was examined in 1965, and a report on her teeth was published in the British Dental Journal.32 This report established, among other things, that Anne exhibited:

congenital absence of upper and lower permanent second molars on the left. There is no sign of these tooth germs or of any relevant disturbance of the bone structure, so that it is clear that the teeth could never have been present. There is no indication of third molars and it is rather probable that these also would have been lacking.33

Rushton was of the opinion that the congenital absence of these particular teeth was a very unusual anomaly. He also stated that congenital absence of teeth is usually an hereditary trait although not necessarily having the same expression in different members of a family.34 One would therefore expect that Anne Mowbray must have shared the trait of congenitally absent teeth with some, although not necessarily with all, of her relatives in one of her family lines. On the basis of her case alone, however, it would be impossible to guess whether the congenital abnormality was inherited from her father’s Mowbray ancestors, from her mother’s Talbot ancestors or from one of her many other lines of descent. If similar dental anomalies were present in the case of CFII, it would suggest that CFII could be one of Anne’s close relatives (and therefore probably Eleanor Talbot) and it would lend support to the proposition that Anne inherited the trait from her Talbot ancestors.

In fact CFII does show some dental peculiarities, including the absence of the left upper second premolar. A dental X-ray examination was conducted by Christine Meadway, BDS, in July 1998. As a result of this examination she offered the following report:

The radiograph was taken using KV6O MA4

Damage to the skull is shown in 543┘ region

The teeth present are:

8 7 6 3 3 4 6 7 8

8 7 6 5 4 3 2 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Caries is present in 5┐. There is evidence of extensive occlusal decay in ┌7 which may have involved the pulp.

└5 is absent. The trabecullar pattern in this region is normal and well defined, although the bone crest is at a lower level than would be expected. └6 shows a normal degree of inclination The space between └4 and └6 is less than would accommodate either a deciduous molar or a permanent premolar.

All occlusal surfaces show a marked degree of attrition.

The interproximal bone pattern is normal showing little evidence of pocketing and peridontal bone loss, although there is flattening of interproximal bone consistent with the amount of attrition.

All the 8s are fully erupted. 8┐ is in close proximity to the inferior dental canal.

Conclusions

• The radiograph is that of an adult, probably in the fourth decade.

• Dental health is fair to good, although there is some evidence of decay. The decay in ┌7 may well have caused some discomfort and would almost certainly have progressed to abscess formation.

• The area in the upper left quadrant with a missing tooth is of some interest. The absence of a permanent premolar, the flattening of the interdental bone margins, the lack of tilting of the first permanent molar and the width of the interdental space all suggest that a deciduous molar was retained into adult life and then subsequently shed. The most common causes of retained deciduous molars are an impacted permanent successor or its congenital absence. Here there is no impacted tooth so the most likely explanation for the radiological appearance is the congenital absence of └5.

• It is possible that the marked attrition of the teeth is due to bruxism but this wear pattern is commonly noted in individuals with a largely unrefined diet.

It thus emerges that CFII probably congenitally lacked her upper left premolar (no. 5). Although the congenital absence of this particular tooth is less rare than the pattern of congenital absence of the left molars which Anne Mowbray exhibits, under the circumstances (place of discovery, age at death, evidence of social status) this dental evidence does tend to reinforce the possibility that the Norwich remains may well be those of Eleanor Talbot, Anne Mowbray’s aunt.

It would assist in establishing for certain from which line of her ancestry Anne Mowbray inherited her congenitally missing teeth if the remains of her parents could be examined. Unfortunately neither of these bodies has come to light. Although the remains of Elizabeth Talbot, Duchess of Norfolk, must have been lying quite close to those of her daughter at the site of the Convent of the Poor Clares (‘the Minories’) at Aldgate, they were apparently not noticed, or at any rate, not identified, when Anne’s body was found in 1965. As for the body of John Mowbray, fourth Duke of Norfolk, that must be presumed to lie still where it was buried, between two of the now ruined piers on the south side of the choir of Thetford Priory. Although the superstructure of his tomb has vanished, its base can be distinguished, but the contents of this tomb have not been investigated.

Human teeth.

In the absence of information regarding the dentition of either of her parents, Rushton, with some reservations, and other writers, with the appearance of greater enthusiasm and certainty, assumed that Anne Mowbray did not inherit her congenitally absent molars from the Talbots. Comparisons have been made between her dentition and those of two persons of uncertain gender and date whose remains were found at the Tower of London in 1674. Although these remains were eventually reburied, on the orders of King Charles II, at Westminster Abbey as those of the ‘Princes in the Tower’, in actual fact their identity is by no means certain so they will be referred to here as Tower of London 1 and 2 respectively (hereinafter TL1 and TL2, TL1 being the remains of the older of the two individuals).

Like Anne Mowbray, TL1 showed congenital absence of teeth. In this case the missing teeth were the upper second premolars on both sides (the left one of which is also absent in CFII) and the lower wisdom teeth on both sides. By comparison with the very unusual dental anomalies of Lady Anne Mowbray, the absence of these particular teeth is considered a not uncommon phenomenon. Indeed, the present writer also exhibits the congenital absence of both lower wisdom teeth. In addition it has been suggested that TL2 also showed the congenital absence of a tooth, but in the opinion of Rushton ‘this cannot be considered proved beyond doubt since the tooth could have been lost early’.35 In the case of TL2 the tooth in question was the lower right deciduous last molar, the absence of which is considered to be quite a common phenomenon. Nevertheless, on the basis of the congenitally missing teeth of TL1 and the possibly congenitally missing tooth of TL2, it has been claimed that TL1 and TL2 must be related to each other and to Anne Mowbray, and hence that TL1 is Edward V and TL2 is Richard, Duke of York.36

Curiously, however, although this fact has not hitherto been picked up by any historian or scientist, new evidence (or the absence thereof) in respect of this contention has recently emerged.37 In terms of teeth, the remains of King Richard III (which were rediscovered in Leicester in 2012, thanks to the Looking For Richard Project, led by Philippa Langley, and of which the present author was a key member) raise doubts over the alleged dental evidence of TL1 and TL2. If the latter really were the remains of the sons of Edward IV and Elizabeth Widville, they would be the bones and teeth of Richard III’s nephews. However, as reported by Rai in the British Dental Journal, the skull of Richard III exhibited no sign of congenitally missing teeth (see plate X). There are some errors in Rai’s article in terms of history.38 Nevertheless, his dental evidence shows that during his lifetime Richard III had possessed a complete set of adult teeth. This suggests that Richard III had no blood relationship with TL1 and TL2. Therefore the bones now preserved in an urn in the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster are not likely to be the remains of Richard III’s nephews.

As for Anne Mowbray, she was indeed related to her husband, Richard Duke of York, and to his brother, in a number of lines of descent. They shared common ancestors in Edward I and Edward III. However, these were relatively remote relationships. Their really close relationship, the one to which Pope Sixtus IV referred when, at the request of Edward IV, he granted a dispensation for Anne to marry Richard,39 was their common Neville descent: Anne’s great grandmother, Catherine Neville, dowager Duchess of Norfolk, and the little Duke of York’s grandmother, Cecily Neville, Duchess of York were sisters.

If those who sought to claim that Anne Mowbray’s congenitally missing teeth proved that she was related to TL1 and 2 (and that therefore these were the remains of Edward V and Richard, Duke of York) had been correct, Anne’s dental anomaly must almost certainly have descended to her via her Neville ancestry – since that was the line of descent which she shared with her young husband and his elder brother. But of course, Richard III was also a Neville descendant (the son of Cecily Neville). Therefore, if the missing teeth were a Neville legacy, it seems odd that Richard III inherited no sign of it.

Moreover, evidence does exist that Anne Mowbray may have inherited her dental anomaly in a different line of descent – a line which she did not share with the sons of Edward IV. It seems that the absence of teeth was, in fact, a Talbot trait. It is recorded that when Anne’s grandfather, John Talbot, first Earl of Shrewsbury, was killed at the battle of Castillon, it was by his missing left molar that his disfigured body was identified. According to the contemporary account of Mathieu d’Escouchy, the earl’s herald was asked to identify his master’s body. He at once felt inside the mouth, and when he found a place on the left side where there was a molar missing, the herald declared that the body was certainly that of Lord Shrewsbury.40

Whether this molar was missing congenitally, or had simply been lost through age or accident, we cannot tell. The surviving account tends to suggest that latter interpretation, but this may have been merely an assumption on the part of the chronicler, who may never have heard of congenitally absent teeth. Nevertheless, it is certainly a very interesting coincidence that the tooth in question was a left molar. Unfortunately when Lord Shrewsbury’s remains were examined in 1874, the point was not addressed. A photograph taken at the time shows few teeth remaining in the skull, but this may be misleading, for the earl’s remains had been several times disturbed since their first burial in France.

It is a pity that this point cannot be more clearly elucidated. If Anne Mowbray did inherit her missing teeth from her grandfather, the first Earl of Shrewsbury, that evidence would undermine any attempt to cite those missing teeth as evidence that TL1 and TL2 are Edward V and his brother. The relationship of the sons of Edward IV and Elizabeth Widville to the Earl of Shrewsbury was extremely remote. (Their most recent common ancestor was King Edward I.) But as we have seen, any attempt to use congenitally missing teeth as evidence for the royal identity of TL1 and TL2 has now already been undermined by the lack of congenitally missing teeth in Richard III’s skull.

Meanwhile, some evidence does exist that certain members of the Talbot family who lived in the fifteenth century exhibited the congenital absence of some back teeth. Taken in association with the evidence of age, diet and lifestyle of the skeleton from Norwich, not to mention its find location, this fact does tend to suggest that the female bones now stored in a cardboard box at Norwich Castle, may indeed be those of Eleanor Talbot. It is an intriguing thought that those bare bones could be the last mortal remains of the beautiful and high-born lady who so captured the attention of Edward IV that the young king, ensnared by his own passions, was led to commit a fatal error which would ultimately topple the royal house of York.