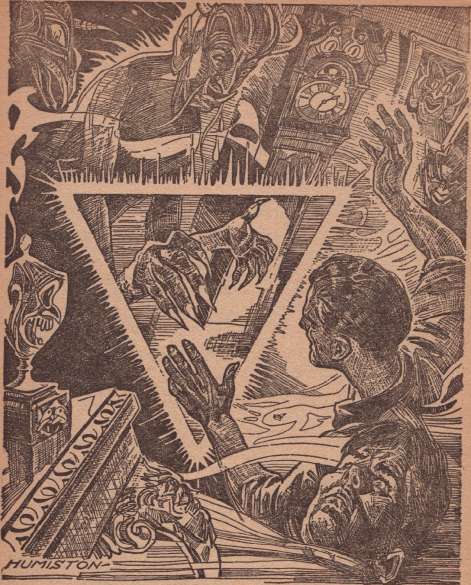

TELL YOUR FORTUNE

15

Don picked it up and read it. He shook his head and passed the card to Mosko and the others. Eventually it got to me.

It was a plain white card with plain lettering on it—but it wasn't regular printing, more like a mimeograph in black ink that was still damp. I read it twice.

WHEN THE BLACK CAT CROSSES YOUR PATH YOU DIE.

That's all it said. The old superstition. Kid stuff.

"Kid stuff!" Don sneered. "Tell you what. This faker musta gummed up the machinery in this scale and put in a lot of phoney new fortune-telling cards of his own. He's crazy."

Tarelli shook his head. "Please," he said. "You no like me. Well, I no like you, much. But even so, I geev you the warning—watch out for black cats. Scales say black cat going to breeng you death. Watch out."

Don shrugged. "You handle this deal, Mosko," he said. "I got no more time to waste. Heavy date this afternoon."

Mosko nodded at him. "Just make sure you don't get loaded. I need you at the tables tonight."

"I'll be here," Don said, from the doorway. "Unless some mangy alley-cat sneaks up and conks me over the head with a club."

For a little while nobody said anything, Tarelli tried to smile at me, but it didn't go over. He tugged at Mosko's sleeve but Mosko ignored him. He stared at Don. We all stared at Don.

We watched him climb into his convertible and back oat of the driveway. We watched him give it the gun and he hit the road. We watched him race by towards town. We watched the black cat come out of nowhere and scoot across the highway, watched Don yank the wheel to swerve out of its path, watched the car zoom off to one side towards the ditch, watched it crash into the culvert, then turn a somersault and go rolling over and over and over into the gully.

There was running and yelling and swearing and tugging and hauling, and finally we found all that was left of 182 pounds and t

brand new suit under the weight of that wrecked convertible. Wc never saw Don's grin again, and we never saw the cat again, either.

But Tarelli pointed at the fortune-telling card and smiled. And that afternoon, Big Pete Mosko phoned Rico to bring Rosa to America.

Ill

SHE arrived on Saturday night. Rico brought her from the plane; big Rico with his waxed mustache and plastered-down hair, with his phoney diamond ring and his phoney polo coat that told everybody what he was, just as if he had a post office reader pinned to his back.

But I didn't pay any attention to Rico. I was looking at Rosa. There was nothing phoney about her black hair, her white skin, her red mouth. There was nothing phoney about the way she threw herself into Tarelli's arms, kissing the little man and crying for joy.

It was quite a reunion downstairs in the back room, and even though she paid no attention when she was introduced to me, I felt pretty good about it all. It did something to me just to watch her smiling and laughing, a few minutes later, while she talked to her old man. Al, the bartender, and the sharpies stood around and grinned at each other, too, and I guess they felt the same way I did.

But Big Pete Mosko felt different. He looked at Rosa, too, and he did his share of grinning. But he wasn't grinning at her— he was grinning at something inside himself. Something came alive in Mosko, and I could see it—something that waited to grab and paw and rip and tear at Rosa.

"It's gonna be nice having you here," he told her. "We gotta get acquainted."

"I must thank you for making this possible," she said, in her soft little voice— the kid spoke good English, grammar and everything, and you could tell she had class. "My father and I are very, very grateful. I don't know how we are going to repay you."

"We'll talk about that later," said Big Pete Mosko, licking his lips and letting his hands curl and uncurl into fists. "But right

WEIRD TALES

now you gotta excuse me. Looks like a heavy night for business."

Tarelli and Rosa disappeared into his room, to have supper off a tray Al brought down. Mosko went out to the big downstairs pitch to case the tables for the night's play. Rico hung around for a while, kidding with the wheel operators. I caught him mumbling in the corner and dragged him upstairs for a drink.

That's where Mosko found us a couple minutes later. Rico gave him the office.

"How's about the dough?" he said.

"Sure, sure. Justa minute." Mosko hauled out a roll and peeled off a slice for Rico. I saw it—five Cs. And it gave me a bad time to watch Rico take the money because I knew Mosko wouldn't hand out five hundred bucks without getting plenty in return.

And I knew what he wanted in return. Rosa.

"Hey, what's the big idea of this?" Rico asked, pointing over at the scales in the corner.

I didn't say anything, and I wondered if Mosko would spill. All week long the weighing machine had stood there with a sign on it, "OUT OF ORDER." Mo?ko had it lettered the day after Don got killed, and he made sure nobody got their fortune told. Nobody talked about the scales, and I kept wondering if Mosko was going to yank the machine out of the place or use it, or what he had in the back of his head.

But Mosko must have figured Rico was one of the family, seeing as how he flew in illegal immigrants and all, because he told Rico the whole story. There wasn't many around the bar yet that early—cur Saturday night players generally got in about ten or so—and Mosko yapped without worrying about listeners.

"So help me, it'sa truth," he told Rico. "Machine'll tell just what's gonna happen to your future. For a stinkin' penny."

Rico laughed.

"Don't give me that con," he said. "Business with Don and the cat was just a what-chacallit—coincidence."

"Yeah? Well, you couldn't get me on

those scales for a million bucks, brother," Mosko told him.

"Maybe so. But I'm not scared of any machine in the world," Rico snorted. "Here, watch me."

And he walked over to the scales and dropped a penny. The pointer went up. 177. The black disk gleamed. I heard the.-hum-ming and the click, and out came the white card. Rico looked at it and grinned. I didn't crack a smile. I was thinking of Don.

But Rico chuckled and handed the card around for all of us to see. It said:

YOU WILL WIN WITH RED

"Good enough," he said, waving the card under Mosko's nose. "Now if I was a sucker, I'd go downstairs and bet this five hundred smackers on one of your crooked wheels, red to win. If I was a superstitious jerk, that is."

Mosko shrugged. "Suit yourself," he said. "Look, customers. I gotta get busy." He walked away.

I got busy myself, then. The marks started to arrive and it looked like a big Saturday night. I didn't get downstairs until after midnight and that was the first time I noticed that Rico must have kidded himself into believing the card after all.

Because he was playing the wheel. And playing it big. A new guy, name of Spencer, had come in to replace Don, and he was handling the house end on this particular setup. A big crowd was standing around the rig, watching Rico place his bets. Rico had a stack of chips a foot high and he was playing them fast.

And winning.

I must have watched him for about fifteen minutes, and during that time he raked in over three Gs, cold. Played odds, played numbers. Played red, and played black too. Won almost every spin.

Mosko was watching, too. I saw him signal Spencer the time Rico put down a full G in blue chips on black to win. I saw Spencer wink at Mosko. But I saw the wheel stop on black.

Mosko was ready to bust, but what could he do? A crowd of marks was watching,

TELL YOUR FORTUNE

17

it had to look legit. Three more spins and Rico had about six or seven Gs in chips in front of him. Then Mosko stepped in and took the table away from Spencer.

"See you in my office," he mumbled, and Spencer nodded. He stared at Rico but Rico only smiled and said, "Excuse me, I'm cashing in." Mosko looked at me and said, "Tail him." Then he shook his head. "Don't get it," he said. He was working the wire now, finding everything in order.

OUT of the corner of my eye I saw Rico over at the cashier's window, counting currency and stuffing it into his pocket. Spencer had disappeared. Rico began walking upstairs, his legs scissoring fast. I followed, hefting the brass knucks in my pocket.

Rico went outside. I went outside. He heard my feet behind him on the gravel and turned around.

"Hey," I said. "What's your hurry?"

Rico just laughed. Then he winked. That wink was the last thing I saw before everything exploded.

I went down on the gravel, and I didn't get up for about a minute. Then I was just in time to see the car pull away with Rico waving at me, still laughing. The guy who had sapped me was now at the wheel of the car. I recognized Spencer.

"It's a frame, is it?" Big Pete Mosko had come up from downstairs and was standing behind me, spitting out pieces of his cigar. "If I'da know what those dirty rats would pull on me—he was working with Spencer to trim me—"

"You did know," I reminded him.

"Did I?"

"Sure. Remember what the fortune-telling card said? Told Rico, 'YOU WILL WIM WITH RED', didn't it?"

"But Rico was winning with both colors," Mosko yelled. "It was that dog Spencer who let him win."

"That's what the card said," I told him. "What you and I forget is that 'Red' is •'s nickname."

went back inside because there wis nothing else to do—no way of catching Rico or Spencer without rough stuff and Mosko

couldn't afford that. Mosko went back to the tables and took the suckers for a couple hours straight, but it didn't make him any happier.

He was still in a lousy temper the next morning when he cut up the week's take. It was probably the worst time in the world to talk to him about anything—and that's, of course, where Tarelli made his mistake.

I was sitting downstairs when Tarelli came in with Rosa and said, ' 'Please, Meestair Mosko."

"Whatcha want?" Mosko would have yelled it if Rosa hadn't been there, looking cool and sweet in a black dress that curved in and out and in again.

"I want to know if Rosa and I, we can go now?"

"Go?"

"Yes. Away from here. Into town, to stay. For Rosa to get job, go to school nights maybe."

"You ain't goin* no place, Tarelli."

"But you have what you weesh, no? I feex machines. I make for you the marvelous scale of fortune, breeng you luck—"

"Luck?" Rosa or no Rosa, Mosko began to yell. He stood up and shoved his purple face right against Tarelli's button nose. "Luck, huh? You and your lousy machine— in one week it kills my best wheel man, and lets another one frame me with Rico for over seven grand! That's the kind of luck you bring me with your magic! You're gonna stick here, Tarelli, like I say, unless you want Uncle Sam on your tail, but fast!"

"Please, Meestair Mosko—you let Rosa go alone, huh?"

"Not on your life!" He grinned, then. "I wouldn't let a nice girl like Rosa go up into town without nobody to protect her. Don't you worry about Rosa, Tarelli. I got plans for her. Lotsa plans."

Mosko turned back to the table and his money. "Now, blow and lemme alone," he said.

They left. I went along, too, because I didn't like to leave Rosa out of my sight now.

"What is this all about, Father?" Rosa asked the question softly as we all three of us sat in Tarelli's little room.

WEIRD TALES

Tarelli looked at mc and shrugged.

'Tell her," I said. "You must."

So Tarelli explained about being here illegally and about the phoney roulette wheels.

"But the machine—the scales of fortune, what do you mean by this?"

Again Tarelli looked at me. I didn't say anything. He sighed and stared down at the floor. But at last, he told her.

A lot of it I didn't understand. About photo-electric cells and mirrors and a tripping lever he was supposed to have invented. About books with funny names and drawing circles in rooster blood and something called evocations or invocations or whatever they call it. And about a bargain with Sathanas, whoever that is. That must have been the magic part.

I guessed it was, because of the way Rosa acted when she heard it. She turned pale and began to stare and breathe funny, and she stood up and shook Tarelli's shoulders.

"No—you did not do this thing! You couldn't! It is evil, and you know the price—"

"Nigromancy, that ees all I can turn to to get you here," Tarelli said. "I do any-theeng for you, Rosa. No cost too much/'

"It is evil," Rosa said. "It must not be permitted. I will destroy it."

"But Mosko, he owns the machine now. You cannot—*'

"He said himself it brought bad luck. And he will never know. I will replace it with another scale, an ordinary one from the same place you got this. But your secret, the fortune-telling mechanism, must go."

"Rosa," I said, "you can't. He's a dangerous customer. Look, why don't you and your old man scram out of here today? I'll handle Mosko, somehow. He'll be sore, sure, but I'll cool him off. You can hide out in town, and I'll join you later. Please, Rosa, listen to me. Look, kid, I'll level with you. I'm crazy about you. I'll do anything for you, that's why I want you to go. Leave Mosko to me."

She smiled, then, and stared up into my eyes. She stood very close and I could smell her hair. Almost she touched me. And then the shook hex head. "You are a good man,"

she said. "It is a brave thing you propose. But I cannot go. Not yet. Not while that machine of evil still exists. It wiil bring harm into the world, for my father did a wicked thing when he trafficked with darkness to bring it into being. He did it for me, so I am in a way responsible. And I must destroy it."

"But how? When?

"Tonight," Rosa said. "Tomorrow we will order a new scale brought in. But we must remove the old one tonight."

"Tarelli," I said. "Could you put the regular parts back in this machine if you take out the new stuff?"

"Yes."

"Then that's what we'll do. Too dangerous to try a switch. Just stick the old fortune-telling gimmick back in and maybe we can get by for a while without Mosko noticing. He won't be letting anybody near it now for a while, after what happened."

"Good," said Tarelli. "We find a time."

"Tonight," Rosa repeated. "There must be no more cursed fortunes told."

But she was wrong.

IV

SHE was wrong about a lot of things. Like Mosko not having any use for the fortune-telling scales, for instance. He lied when he told Tarelli the machine was useless.

I found that out later the same afternoon, when Mosko cornered me upstairs in the bar. He'd been drinking a little and trying to get over his grouch about the stolen money.

"I'll get it back," he said. "Got a gold mine here. Bigges' gold mine inna country. Only nobody knows it yet but you and me." He laughed, and the bottles rattled behind the bar. "If that dumb guy only could figure it, he'd go crazy."

"Something worked up for the fortune-telling?" I needled.

"Sure, Look, now. I get rich customers in here, plenty of 'em. Lay lotsa dough onna line downstairs. Gamblers, plungers, superstitious. You see 'em come in. Rattling lucky charms and rabbits-foots and four leaf

TELL YOUR FORTUNE

19

clovers. Playin* numbers Like 7 and 13 on hunches. What you think? Wouldn't they pay plenty for a chance to know what's gonna happen to them tomorrow or next year? Why it's a natural, that's what—I can charge plenty to give 'em a fortune from the scales. Tell you what, I'm gonna have a whole new setup just for this deal. Tomorrow we build a new special room, way in back. I got a pitch figured out, how to work it. We'll set the scales up tomorrow, lock the door of the new room, and then we really operate."

I listened and nodded, thinking about how there wasn't going to be any tomorrow. Just tonight,

I did my part. I kept pouring the drinks into Mosko, and after supper he had me drive him into town. There wasn't any play on the wheels on Monday, and Mosko usually hit town on his night off to relax. His idea of relaxation was a little poker game with the boys from the City Hall—and tonight I was hot to join him.

We played until almost one, and I kept him interested as long as I could, knowing that Rosa and Tarelli would be working on the machine back at the tavern. But it couldn't last forever, and then we were driving back and Big Pete Mosko was mumbling next to me in the dark.

"Only the beginning, boy," he said. "Gonna make a million off that scales. Talk about fortunes—I got one when I got hold of Tarelli! A million smackers and the girl. Hey, watch it!"

I almost drove the car off the road when he mentioned the girl. I wish I had, now.

"Tarefli's a brainy apple," Mosko mumbled. "Dumb, but brainy—you know what I mean. I betcha he's got some other cute tricks up his sleeve, too. Whatcha think? You believe that stuff about magic, or is it just a machine?"

"I don't know," I told him. "I don't know nothing about science, or magic, either. All I know is, it works. And it gives me the creeps just to think about it—the scales sort of look at you, size you up, and then give you a payoff. And it always comes true." I began to pitch, then. "Mosko, that thing's dangerous. It can make you a lot

of trouble. You saw what it did to Don,

and what happened to you when Rico had his fortune told. Why don't you get rid of it before something else happens? Why don't you let Tareili and Rosa go and forget about it?"

"You going soft inna head?" Mosko grabbed my shoulder and I almost went off the road again. "Leave go of a million bucks and a machine that tells the truth about the future? Not me, buddy! And I want Tarelli, too. But most of all I want Rosa. And I'm gonna get her. Soon. M.iybe— tonight."

What I wanted to do to Big Pete Mosko would have pinned a murder rap on me for sure. I had to have time to think, to figure out some other angle. So I kept driving, kept driving until we pulled up outside the dark entrance to the tavern.

Everything was quiet, and I couldn't see any light, so I figured whatever Rosa and Tarelli had done was finished. We got out and Mosko unlocked the front door. We walked in.

Then everything happened at once.

I heard the clicking noise from the corner. Mosko heard it, too. He yelled and grabbed at something in the dark. I heard a crash, heard Tarelli curse in Italian. Mosko stepped back.

"No you don't!" he hollered. He had a gun, the gun had a bullet, the bullet had a target.

that's all.

Mosko shot, there was a scream and a thud, and then I got the lights on and I could see.

I could see Tarelli standing there next to the scales. I could see the tools scattered around and I could see the queer-looking hunk of flashing mirrors that must have been Tarelli's secret machinery. I could see the old back of the scales, already screwed into place again.

But I didn't look at these things, and neither did Mosko and neither did Tarelli.

We looked at Rosa, lying on the floor.

Rosa looked back, but she didn't see us, because she had a bullet between her eyes.

"Dead!" Tarelli screamed. "You murder her!"

WEIRD TALES

Mosko blinked, but he didn't move. "}iow was I to know?" he said. "Thought somebody was busting into the place. What's the big idea, anyhow?"

"Ees no idea. You murder her."

Mosko had his angle figured, now. He sneered down at Tarelli. "You're a fine one to talk, you lousy little crook! I caught you in the act, didn't I—tryin* to steal the works, that's what you was doing. Now get busy and put that machinery back into the scales before I blow your brains out."

Tarelli looked at Mosko, then at Rosa. All at once he shrugged and picked the little box of mirrors and flashing disks from the floor. It was small, but from the way he hefted it I could tell it was heavy. When he held k, k hummed and the mirrors began to slide every which way, and it hurt my eyes to look at it.

Tarelli lifted the box full of science, the box full of magic, whatever it was; the box of secrets, the box of the future. Then he smiled at Mosko and opened his arms.

The box smashed to the floor.

There was a crash, and smoke, and a bright light. Then the noise and smoke and light went away, and there was nothing but old Tarelli standing in a little pile of twisted wires and broken glass and tubes.

Mosko raised his gun. Tarelli stared straight into the muzzle and grinned.

"You murder me too now, eh? Go 'head, Meestair Mosko. Rosa dead, the fortune-telling maching dead, too, and I do not weesh to stay alive either. Part of me dies with Rosa, and the rest—the rest was machine."

"Machine?" I whispered undei my breath, but he heard me.

"Yes. Part of me went to make machine. What you call the soul."

Mosko tightened his finger on the trigger. "Never mind that, you crummy little tat! You can't scare me with none of that phoney talk about magic."

"I don't scare you. You are too stupid to un'rstand. But before I die I tell you one theeng more. I tell your fortune. And your fortune is—death. You die too, Meestair Mosko. You die, too!"

Like a flash Tarelli stooped and grabbed

r

the wrench from the tools at his feet. He lifted it and swung—and then Mosko let him have it. Three slugs in a row.

Tarelli toppled over next to Rosa. 1 stepped forward. I don't know what I'd of done next—jumped Mosko, tried to kill him with his own gun. I was in a daze.

Mosko turned around and barked. "Quit staring," he said. "Help me clean up this mess and get rid of them, fast. Or do you wanna get tied in as an accessory for murder?"

That word, "murder"—it stopped me cold. Mosko was right. I'd be in on the deal if they found the bodies. Rosa was dead, Tarelli was dead, the scales and their secret was gone.

So I helped Mosko.

I helped him clean up, and I helped him load the bodjes into the car. He didn't ask me to go along with him on the trip, and that was good.

Because it gave me a chance, after he'd gone, to go to the phone and ring up the Sheriff. It gave me a chance to tell the Sheriff and the two deputies the whole story when they came out to the tavern early in the morning. It gave me a chance to see Big Pete Mosko's face when he walked in and found us waiting for him there.

THEY collared him and accused him and he denied everything. He must of hid the bodies in a good safe place, to pull a front act like that, but he never cracked. He denied everything. My story, the murders, the works.

"Look at him," he told the Sheriff, pointing at me. "He's shakin' like a leaf. Outta his head. Everybody knows he's punchy. Why the guy's off his rocker—spilling a yarn like that! Magic scales that tell your fortune! Ever hear of such a thing? Why that alone ought to show you the guy's slug-nutty."

Funny thing is, I could see him getting to them. The Sheriff and his buddies began to give me a look out of the corner of their eyes.

"First of all," said Mosko, "There never was no such person as Tarelli, and he never

TELL YOUR FORTUNE

had a daughter. Look around—-see if you can find anything that looks like we had a fight in here, let alone a double murder. All you'll see is the scales here. The rest this guy made up out of his cracked head."

"About those scales—" the Sheriff began.

Mosko walked over and put his hand on the side of the big glass dial on top of the scales, bold as you please. "Yeah, what about the scales?" he asked. "Look 'em over. Just ordinary scales. See for yourself. Drop a penny, out comes a fortune. Regular stuff. Wait, I'll show you."

WE ALL looked at Mosko as he climbed up on the scales and fumbled in his pocket for a penny. I saw the deputies edge closer to me, just waiting for the payoff.

And I gulped. Because I knew the magic was gone. Tarelli had put the regular works back into the scales and it was just an ordinary weighing machine, now. HONEST WEIGHT, NO SPRINGS. Mosko would dial a fortune and one of the regular printed cards would come out.

We'd hidden the bodies, cleaned up TarelH's room, removed his clothes, the tools, everything. No evidence left, and nobody would talk except me. And who would believe me, with my crazy guff about a magic scales that told the real future? They'd lock me up in the nut-house, fast, when Mosko got off the scales with his fortune told for a penny.

I heard the click when the penny dropped. The dial behind the glass went up to 297 pounds. Big fat Mosko turned

and grinned at all of us. "You see?" he said.

Then it happened. Maybe he was clumsy, maybe there was oil on the platform, maybe there was a ghost and it pushed him, I don't know. All I know is that Mosko slipped, leaned forward to catch himself, and rammed his head against the glass top.

He gurgled once and went down, with a two-foot razor of glass ripping across his throat. As he fell he tried to smile, and one pudgy hand fumbled at the side of the scales, grabbing out the printed slip that told Big Pete Mosko's fortune.

We had to pry that slip out of his hands —pry it out and read the dead man's future.

Maybe it was just an ordinary scale now, but it told Mosko's fortune, for sure. You figure it out. All I know is what I read, all I know is what Tarelli's scale told Mosko about what was going to happen, and what did happen.

The big white scale stood grinning down on the dead man, and for a minute the cracked and splintered glass sort of fell into a pattern and I had the craziest feeling that I could see Tarelli's face. He was grinning, the scale was grinning, but we didn't grin.

We just pried the little printed slip out of Big Pete Mosko's hand and read his future written there. It was just a single sentence, but it said all there was to be said.... :

"YOU ARE GOING ON A LONG JOURNEY."

// it wasn't a djinn, it certainly was a reasonable facsimile thereof.

<£>■*

jinn and Bitters

05m. ^hrcirold cJUctwior*

I

BY SOME process of feminine logic that I cannot figure out to this day, Connie has decided that the whole weird episode in which we were involved at Alamosa Beach is entirely the fault of Bill Hastings.

Now Bill is a nice guy, one of the best, and to insist as Connie does that everything that went wrong can he laid at his door, when he obviously plays no real part in this story at all, as you can judge for yourself if you'll only read, is to extend the ridiculous to the uttermost limit.

But, Connie says in rebuttal, didn't Bill lend us his cottage *at the shore for oux honeymoon? And wasn't it at the shore that

Heading by Jon Arfstrora

we found the bottle of amethyst glass? And wasn't it after we found the amethyst glass bottle with its surprising contents that all our troubles began?

"Well, then!" Connie has a way of saying, ending the argument.

Surely you can see that such logic is irrefutable? Particularly if you're a married man yourself?

I'm afraid Connie will never forgive Bill for blacking my eye at the ushers* dinner

WEIRD TALES

the night before the wedding, though personally I never held it against him for it was purely and simply an accident, and we were all shellacked at the time. Besides, he no more meant to black my eye, I'm sure, than I intended to tear his ear, which after all, did no great harm except that it didn't improve his looks any, and he was going to be the best man. But then, come to think of it, his looks weren't anything to write home about to begin with.

I tried to point this out to Connie afterward.

"Keep still, Pete Bartlett!" she said. "I was never so mortified in all my life as I was this morning when I came moseying up the aisle and saw you standing in the chancel. What a sight for the eyes of a blushing bride! Tsk, tsk!" At the memory, her brows swooped toward the bridge of her nose. "That drunken bum, Bill Hastings!"

"But, honey. 1 hit him first."

"That's it! Stick up for him!"

Ah, well. What was the use?

"Let's not fight on the first day of our honeymoon, baby," I said tenderly.

WE'D been married at ten o'clock that morning, left the reception at two, and now two hours later we were both lying on the warm sands of deserted Alamosa Beach, basking in the late afternoon sun. It had been a popular vacation spot in its day, but that day was long since past. Except for Bill's cottage where we were staying, the few other shacks high on the dunes behind us were deserted. There were still a few guests, we had been told, in the rkkety old hotel at the far end of the beach. But that was around a bend in the shore, and the hotel and its guests were out of our sight and we were out of theirs.

This made it convenient whenever I felt like kissing Connie, which I'm bound to say was often. For she detests love-making in public.

But now, in the intervals between kisses, we were lying'flat on our backs, with Connie at right angles to me, her bright-penny held resting none too comfortably on my stomach. We were talking of this and that, and she was letting the sands drift idly through

her hands. First she'd plunge them in, palms down, and then she'd turn them, bringing up palmsful of the golden grains only to let them spill in drifts through her slightly spread fingers.

And that was how she found the bottle.

Her fingers encountered something hard, and she burrowed deeper into the sand, dredging up at last a bottle. It was of amethyst glass with little air-bubbles embedded in the crystal. But though the air-bubbles showed up plainly when you held the bottle up against the light, it wasn't possible to see into it. It bore no labei, and it was very tightly corked.

"Dear me," Connie said thoughtfully, holding the thing aloft. "The Morton luck."

"You're a Bartlett now," I reminded her fondly.

"Why, so I am. But my luck still holds."

"You mean it's got Scotch in it?"

"Try to climb onto a spiritual plane, dear, for once in your life," Connie said. "Scotch, indeed! No. But there'll be a djinn in it, of course, who'll have to '^rant me whatever I wish for. Wait and see. I've always been lucky, haven't I? Remember the time I found the purse with seventy-nine cents in it on the park bench? And the night I found the woman's slipper in the Bijou Theater? And—"

"—this morning, when you got me up to the altar?"

"Which I'll live to regret, no doubt," Connie smiled. "Weil, anyway, A djinn. Think of it, dear."

I didn't think much of it.

"Suppose you pull the cork out?" I yawned. "And then we can both relax again."

"I've married a man with no imagination whatever," complained Connie to the sad sea waves.

But she proceeded to withdraw the cork as I'd told her, and so help me, there really was something in the bottle. I felt a peculiar sensation that wasn't entirely pleasant in the small of my back and all along the channel of my spine as I watched a thin trickle of gray vapor emerge from the bottle, and slowly begin to rise above it.

The thick mist rose higher still till it was

©JINN AND BITTERS

25

hovering above us, grew denser, and began to form into a shape resembling something remotely human—something like that of the rubber man in the old Michelin tire advertisements.

It was no thing of great beauty, but if it wasn't a djinn, I thought dazedly, it was certainly a reasonable facsimile thereof. I stared at the thing, open-mouthed. I was speechless, I'll admit.

But Connie wasn't. Connie never is.

"See, Pete?" she said. "Your sneer, and your cheap cynicism!"

NOW I want to stop here a moment to indulge myself in a seemingly pointless digression, though I assure you that it really isn't. I have a confession to make, and it is this: I'd had serious qualms about marrying Connie.

Much as I loved her, the Bartlett head is never so completely overruled by its heart that I couldn't see Connie was flippant and frivolous and flutter-brained, with the emotions, undoubtedly shallow, of a child. You are please not to believe that I'm trying to set myself up here as her superior. I've had my bird-brained moments, too, and plenty of them. You have only to consider my behavior on the eve of our marriage, as an illustration of that.

But with marriage, I'd always known that I wanted to settle down, to mature, to grow serious—and wiser, too, if possible.

Many's the time after I had proposed to Connie that I'd wake up in the small gray hours of the morning, beset by serious doubts. I knew I'd never be happy for long with Connie if she didn't change. In the beginning I'd be willing to take it slowly, to match her flippancies, to be as light-hearted and light-minded as she. But would she mature? Could I change her?

Certainly it would have been a slow process. Certainly I owe a debt to the djinn.

For it was a djinn, all right, that the bottle had contained.

He yawned and stretched now, and almost immediately winced.

"Ouch!" he said, in a voice like the mutter of distant thunder. "Am I cramped! Oof, my lumbago! Just keep your shirt on there

with your wish for a moment, will you, until I pull myself together?" he asked crankily, his eyes squinted shut, seemingly with pain.

Connie sat up, hugging her satiny knees. I sat up, too, bracing myself with backward-thrust arms. I would have fallen down, otherwise, for I assure you it's startling to learn that you have unwittingly released a djinn. I should have doubted the evidence of my senses, but the sun blazed brightly so that I was forced to squint against it, and there came the sharp salt fishy smell of the sea to sting my nostrils, and the sand was hot beneath my legs.

Yes, I told myself, I was conscious, all right, difficult though I found it to believe ■—with a djinn hanging heavy over our heads like a forfeit in a game that children play.

THE silence that followed could only be described as pregnant, unbroken save for the soft wash of the sea against the shore. You may judge for yourself of the effect that the djinn had upon us when I tell you that even Connie was silent, for a change.

"What a life!" the djinn said gloomily, after a moment. He seemed to ruminate, lost in depression.

Deep within me I found my voice. I dragged it out with an effort. I sought to cheer him. "You think you've got it tough? You should try living in the postwar world."

This seemed to nettle him. He reared back as it stung, regarded me with some dudgeon. "Z have a nice life, you're telling me? Hah! Bottled up like a pickled onion till I ask myself, am I working for Heinz?" He held up a smoky hand to forestall interruption. "And that isn't all," he went on, warming to the task as he recited the litany of his grievances. "Now I'll have to work my silly head off to grant the wish, which is sure to be foolish and unreasonable, of whomever it was that released me."

"Poor you!" Connie said softly. '7 released you."

The djinn seemed to see her for the first

WEIRD TALES

time, and it must be recorded that even in his depression his eyes visibly brightened. I'm afraid any masculine eyes would brighten at the vision of Connie tastefully girbed in a brief blue-and-white polka-dotted Bikini bathing suit. Indeed, I've had trouble with this angle before.

"Well, wed, well!" said the djinn, shaking his head in seeming despond, though it was plain to be seen that he was not really distressed. "What'll they be taking off next?"

This was a rhetorcial cjuestion, purely, I gathered. But as it seemed to be addressed more or less in my direction, I thought it would do no great harm to straighten him out immediately on a few salient facts.

"This little lady happens to be my wife, repeat wife," I said.

"Oh!" For a minute the disappointment seemed almost more than the djinn could bear. But he must have been a philosopher of sorts for after a minute he said, though somewhat obscurely, "Ah well. That's life for you."

I settled back into my former state of uneasy calm, my suspicions not entirely allayed. This was one humbre, I warned myself, who would probably bear watching.

CONNIE noted my scowl, and proceeded to pour oil on troubled waters.

"The djinn was only being complimentary," she said. "No need for you to be jealous all the time, Petey-weetie-sweelie."

"If there's one thing I can't abide," I said fretfully, my nerves quivering like the fringe on a bubble-dancer's G-string, "it's being called Petey-weetie-sweetie in front of strangers."

"Oh, come, now!" the djinn protested, looking somewhat hurt. "Don't look upon me as a stranger, I implore you! Until I grant your wife's wish, which automatically releases me, I'm practically one of the family."

"Not this family," I said sullenly.

Connie said, not displeased with all this, "Now, boys Let's leave this silly argument lie for a moment, while we consider the main question."

"What main question?" I asked-

"The wish, stupid, the wish!"

"Business, always business," the djinn said, gloomy once more. "Well let's get on with it then. The sooner I grant your wish, the faster I can take a powder. What can I do for you? Seeing it's you, it'll be a pleasure almost, despite my griping."

And he looked almost amiable, even indulgent.

Connie thanked him, but she was not to be hurried. She likes to talk over all sides of a question before acting, Connie does. In fact, she likes to talk, period. She sat there in the sand now, her hands absently caressing the satiny skin of her knees, the while a dreamy look came into her large turquoise eyes. And I knew that when she did speak at last, whatever it was she would say would be the end-product of no little musing and considered thought. And Connie has a talent for the bizarre.

The djinn felt this, too, I am sure. I confess to a feeling of no little apprehension as we both waited on the well known tenterhooks.

"You know," Connie began at last conversationally, "I've often read stories about people who'd released djinns from bottles, and it really does seem to me that they're incredibly stupid. The releasers, I mean, not the stories or the djinns or the bottles. For consider! What do the releasers do? Do they consider even the minimum of intelligence in selecting their wish for the djinn to grant? They do not!" She answered herself, before we could open our mouths. "They wish for some silly thing like a million dollars, or something like that."

"A million dollars is silly?" I croaked. "Well, now, here's news!"

Even the djinn looked somewhat taken aback. "I can think of sillier things," he said defensively.

"Well, perhaps a million dollars isn't so very silly," Connie hedged.

"You're tootin', baby," I said. "For a minute there I thought you'd gone crazy in a big way."

"But the point I'm trying to make is this," Connie went on, patient with my levity. "These people just wish for something sil— something like that, and they neglect to wish

DJINN AND BITTERS

27

for what seems to me to be the most obvious wish of all. One that should occur to anybody immediately, with little or no thought. Anybody, that is with even a grain of common-sense,"

I didn't get it. I don't think the djinn did, either, though he must have had his misgivings, for:

"Something tells me this wish is going to be a stinker," he said dolorously. "You should forgive the expression."

"Cheer up, man, for heaven's sake!" I barked. "What have you got to be bleating about? Have a thought for me! Allah only knows what Connie will wish for, and I've just elected to spend the rest of my Hfe with her."

"She makes you nervous, eh?" the djinn asked, with a trace of commiseration in his booming voice.

"Highly," I said. "Highly." I wiped the perspiration that had seeped out on my brow. "Now listen, Connie," I warned. "I can feel my arteries hardening by the second. All I ask is, if you love me, have a care what you wish for."

"There's nothing to get into such a turmoil and hurly-burly about," Connie said. "I'm merely going to wish a wish. A quite reasonable, logical wish that would occur to any woman. All the men who've opened djinn bottles, with all their fine masculine blather about logic, poor tilings, have never wished a wish like this."

THE djinn sucked air through his teeth reflectively. He said to me, "You take a woman, now. You never can tell which way she'll jump next."

"I need to learn about women from you?" I asked bitterly. **My life has been cluttered with 'em, clattered."

"Oh, it has, eh?" Connie said, sitting up straight.

For a minute I didn't notice the danger signal, but plunged on recklessly, "And haven't I driven behind them on the public highways, which alone would be educational enough?" I asked.

"I've made a mental note of all this, never fear," Connie said ominously. "Superior, beasts, men. Lords of creation. But

if they're so brilliant, why didn't any of them ever wish for a wish like this?"

I looked at the djinn. "Well, I guess we've postponed the evil moment as long as we could. Shall we proceed?"

"Where do you get that \ve' stuff?" the djinn asked coldly, "This is my headache, just in case anybody rides up on a white horse to ask you. Well, I've tried to steel myself, so go ahead, Connie. I only hope I can stand it."

"Yes, dear. Tell us," I said.

" "Us/ " quoted the djinn witheringly.

Connie moistened her red lips with her little pink tongue. I waited, breath in abeyance. The sun shone, the sea smelled, the sand burned, just as I've told you. I was surely conscious.

Connie drew a deep breath. "Well, the wish is merely and simply this. I merely wish you to grant me all the wishes I wish to wish!"

in

THE djinn leaped like a startled gazelle. The howl he emitted was really ear-piercing. Almost could I find it in my heart to feel sorry for the man.

"I merely and simply say nix!" he bawled. "Good Gad! I never heard of such a thing! It's enough to make reason totter on its throne! It's unethical, that's what it is! It's unconstitutional! Why, it's—probably even communistic, even!"

He was waxing incoherent, and who could blame him?

"Oh, nonsense!" Connie said.

"I tell you I won't do it!" the djinn said with considerable asperity.

Connie's eyes narrowed until the irises were only slivers of turquoise beneath her breath-taking lashes. "Just tell me one thing, djinn. Do you or do you not positively have to grant me any wish I wish to wish?"

He couldn't meet her eyes. "I—I guess I do," he said reluctantly. And he murmured something else about an old Arabian law.

"Okay." Connie dusted her palms. "You heard me, bud. I wish you to. grant me all the wishes I wish to wish."

"I been takeaJ" moaned the djinn.

WEIRD TALES

"In any future battle of the sexes," Connie said smugly, "I give you both leave to remember this day."

"And rue it," said the djinn sadly. "Why, I'll be hanging around here forever, like a grape on the vine." And yet, despite his complaints, he must have felt an unwilling admiration for Connie, for he looked at me and said, albeit dolefully, "That's one smart-type tomato you got there, fella. Married to her, I'd hang onto my gold teeth with both hands, if I were you."

I had been considering Connie's wish all this while, and it seemed to me that even for her it made sense. I felt happiness and a deep contentment welling within me.

I smiled complacently. "It seems to me that this is between the djinn and you, Connie. I swear my nervousness is all gone. No need for me to get upset. No skin off my nose, that I can see. You ask me, I'm sitting pretty with a wife who can get me anything I wish for. I have only to relay them to her, and then—"

"You're babbling," Connie said, in an odd tone of voice.

This gave me pause. I looked at her. She was eyeing me in a very strange, reflective sort of way. Even the djinn must have noticed it, for he looked momentarily diverted from his own woes.

"One thing I can't stand," the djinn said, "is a winner who gloats. You're planning to give Pete his come-uppance, Connie?" I still didn't like that thoughtful look on Connie's face. I cleared my throat nervously. "I did something, maybe?" I asked. "I said something?"

"The time to train a husband," said Connie at a tangent, "is right from the very beginning of the marmge."

The djinn began gleefully snortling and snuffling to himself in a manner that I found altogether revolting.

"You have something in mind, Connie?" asked the djinn.

"Oh, nothing definite. But I do have a hopeful feeling that something about all this business will cause Pete more than a spot or two of mental anguish."

"Constance Bartletr," I said, aghast. I shivered. I must have known even then, in-

tuitively, that she was speaking with the voice of a prophet, and no minor one, at that. But what did I do?"

"Women have cluttered your life, huh? We can't drive, huh?"

She prolonged the "huhs" nastily like a cop in the movies giving someone the third degree. I can't say that I liked it.

Still it wasn't serious. I said, with somewhat more assurance, "Now honey. You know I didn't mean a thing by it. I was just—just being witty."

"Why didn't I laugh?" Connie asked reasonably.

I'm afraid the sound the djinn made at that could only be described as a giggle. A hoarse, muttering, mumbling, rumbling, rasping racket, if you like, but a giggle fat all that.

I withered him with a look before turning back to Connie. "This isn't like you, dear. Give me some sign that you forgive me."

But if I were attempting to appeal to her better instincts, she apparently didn't have any.

"You don't even begin to know what I'm like, but oh, brother! are you going to learn!" Connie said. "However, just to show you my heart's in the right place, would you like a drink?"

"I wish I had one right now," I said. And God knows I needed it.

Connie looked at the djinn. "I wish Pete could have his wish."

"Work, work, work," grumbled the djinn. "A body can't have a minute's rest." I felt something cold and wet in my hand. It was like touching a dog's nose unexpectedly in the dark. I looked down, unnerved.

IT WAS a crystal glass, its sides becomingly dew-beaded, its contents smelling delightfully of something pungently alcoholic. I blinked at it stupidly. There was a moment's pause while manfully I pulled together my reflexes, sadly scattered long since, before I could lift the glass to my lips and take a snort.

My Adam's-apple hobbled in delightful surprise. I rolled my eyes beautifully.

DJINN AND BITTERS

29

Scotch, by Gad! Good Scotch, too.

"How is it?" asked the djinn professionally, with the air of a man beginning to take a little pride in his work.

"Delectable, delectable!" I muttered absently, my mind spinning tike a waltzing mouse. I looked at Connie with awe. "You know, life could be beautiful, dear. I wish—"

"Don't go running a good thing into the ground," Connie warned maliciously.

My heart sank. She had not yet really forgiven me for my ili-chosen remarks about women. She was merely demonstrating her powers tantalizingly in a way to make them stick in my memory. To think that I thought then that the situation was grave! Had I but known, as they say in the mystery novels!

For worse was yet to come.

IT BEGAN at once with the flashing speed of an attack from a coiled rattlesnake. I was not forewarned. The thing was upon me before I knew it.

"Well," Connie said, rising, "I suppose I'd better go in and dress. It's getting late."

The djinn rose too, and hovered over her. This brought me up with a jerk.

"Where do you think you're going?" I asked him.

"Until I'm released, I have to hover at Connie's beck and call, don't I?" he whined.

"You don't have to hover at her beck and call while she's changing her clothes, oaf!"

"Did I make the rules?'* he asked me.

Connie giggled.

"Now, listen!" I said, dropping my glass as I scrambled hastily to my feet. "Now hold on here a minute! Connie! Have you taken leave of your senses?"

"Why, no." Connie paused, eyes demurely cast down, appearing to give this some thought. "I believe I'm in my right mind."

"You are like h— you are not in your right mind if you think for one minute that I propose to allow you to change your clothes in front of this—this—!"

"I can't spend the rest of my life in a Bikini bathing suit, either, can I?" Connie asked reasonably.

For the first time since I'd met him, the djinn looked completely happy. * 'You

know," he said, "there must be tougher ways than this of earning a living, at that. I take it all back."

The effrontery of the man! The effrontery of both of them, come to think of it!

"By Jupiter!" I cried. "This is insupportable! And on our honeymoon, too! Constance Bartlett, I positively forbid you—"

"Now, wait a minute," the djinn interrupted me smoothly. "There's no real need for all this heat and passion, this deplorable running off at the mouth. Really, I marvel at you, Pete! You, too, Connie! Where is the famous Bartlett logic, the Bartlett <juick wit?"

"You mean?"

"I mean there's a very easy, simple, quick way out of this difficulty," the djinn said slyly. "Pshaw! I'm disappointed in both of you! Thinkl"

Connie looked wary, but I said recklessly, "Name it!"

"All Mrs. B. has to do," the djinn said, spreading his hands expressively, "is wish for me to go away from here promptly."

I would have leaped unwittingly at the suggestion, but Connie forestalled me.

"Oh-ho, no you don't!" she cried. "Was I born yesterday? Don't think you can teach your grandmother how to suck eggs, djinn! I should tell you to go away before I've even wished a single profitable wish! Get tost with that idea, chump!"

The djinn lapsed into sullen impotence. I groaned aloud in my frustration. We seemed to have reached an impasse.

IV

"OUT like many difficult problems, once -»-' attacked, the solution itself was so simple that it would have occurred to a Mongolian idiot.

"I'm-getting hungry," Connie said plaintively. "We can't hang around here all day. This discussion must end right now. I'm going up to the cottage and change my clothes, and I dare anybody to try to stop me!"

And this time she didn't wait for further argument. She trudged through the sand as swiftly as may be, the djinn hovering

WEIRD TALES

tenaciously and smokily above her, while I perforce brought up the rear of this weird caravan, moaning unhappily to myself, and grimly determined to leave neither of them out of my sight if it killed me.

But the sensibilities of even the most modest would never have been wounded.

In the cottage, Connie merely slit a hole in a blanket, slipped it eoshroudingly over her shoulders so that only her head protruded, and demurely proceeded to change her clothes within the shelter of its enveloping folds.

"Shucks!" said the djinn sulkily.

It had been shameful of me to suspect for even a moment that I couldn't trust Connie. Scarcely containing my relief, I went to change my own clothes. When I came out of the bedroom, dressed in slacks and sport shirt, Connie suggested we go down to the hotel dining room for dinner.

It wasn't much of a place, and Duncan Hines would certainly never recommend it, but as the French say, what would you? It was impossible to cook dinner in the cottage for, as Connie pointed out, the djinn was large and the cottage was small, and as a result he seemed to fill the place with smoke and fog,

"What do you think he's going to do to the hotel dining room?" I wondered.

"Don't cross your bridges until they're hatched," Connie said gayly.

"But how are we ever going to explain the djinn?" I wanted to know.

" 'Who excuses, accuses,' " Connie quoted airily. "We simply won't say a word about him. We can recognize him because we let him out of the bottle, but to anyone else he'll justiook like a mass of smoke or fog, for you'll have to concede that he isn't very shapely."

"Is that so!" roared the djinn, stung.

"So you see?" Connie said, ignoring his hurt. "We don't have to know any more about it than anyone else, do we?"

This was true enough, so I made no further demur.

Still and all, Tm afraid our entrance into the dining room was as unobtrusive as a platinum blonde at an Abyssinian hoe-down.

People started coughing and gasping, and waving their hands in front of their faces, trying futilely to dispel the gray vapor that filled the place and seemed willfully bent upon choking them.

"Did you ever see such a fog?" they kept asking each other. They even asked us, thus confirming us in our belief that they suspected nothing.

I daresay we looked, to the naked eye, like a perfectly normal young couple, though closely accompanied by a persistent and overhanging thunder-cloud. However, its proximity to us, while mystifying, seemed to arouse no suspicion among the others.

We settled ourselves at a table, and looked about us, and I must confess that our hearts sank.

Connie regarded with a lacklustre eye the sagging walls, the splintered floor, the dirty streamers hanging from the ceiling in a ghastly travesty of gaiety. The orchestra, if such it could be called by courtesy, made weirdly unrecognizeable sounds and wheez-ings that only assailed the ear-drums, and the few couples circling the floor in some grisly gavotte of their own devising could best be described by saying that they were both elderly and unprepossessing.

Through the open French doors, flowers and vines had withered in the boxes allegedly decorating the dilapidated terrace, and the dusk outside seemed alien and unfriendly. Even the sea looked gray and sullen, and now that the sun had gone down, the sky was only a shade lighter than the water.

No setting for romance, this.

"Oh, I wish there was a beautiful moon, at least," Connie said wistfully, sighing. "A honeymoon, Pete, just for us."

It hung in the sky immediately, a great golden ball.

Connie apparently didn't see it at once, for her face was rapt with the picture she was blissfully regarding in her mind's eye. She went on, "And I wish these people were all young and handsome and beautifully dressed—"

They were. At once.

"—dancing to the strains of a wonderful orchestra—"

DJINN AND BITTERS

31

The music was suddenly marvelous.

"—over a floor like satin, in a gorgeous room, hung with brilliantly-lighted crystal chandeliers!"'

The glare was blinding. Connie roused from her dream.

"Look!" I said needlessly.

For a minute she seemed nonplussed as she saw her vision of beauty had come true. And then she smiled, and said aloud, "Dear me, I keep forgetting! Thank you, djinn."

"For you, Connie, anything!" the djinn said.

Connie looked hungrily, feasting her beauty-starved eyes, before turning to me. " 'Every prospect pleases, and only man is vile,"' she quoted prettily.

"Do you have to look at me when you say that?" I asked peevishly.

Connie dimpled. "It's just that the room is so beautiful now I can't help wishing that you combined the charm of Charles Boyer, the physique of Victor Mature, and the looks of Tyrone Power, just to go with it."

Before either of us knew what was happening, every woman in the place was swarming all over me, running their fingers through my hair, smearing my face with lip-sticky kisses, and so forth and so on. I'm not complaining, mind! It wasn't really disagreeable, just startling. The din was terrific but loud above the cries of the maddened women came Connie's voice almost instantly, clarion-clear: "So help me, I wish I'd kept my big mouth shut before I ever wished a wish as silly as that one!"

I might have known it was too good to last. Before you could say Jack Robinson, I was back in the old body, battered but still serviceable, and no woman in the room was giving me even a second glance.

Connie was fanning herself. She looked cjuite distraught. "Good heavens, what a sight!" she murmured. "I'll have to watch what I wish for, after this." The djinn was grinning. "You might have given me five minutes more, Connie, before calling it off," I said, and to save myself I couldn't keep a querulous note from creeping into my voice. **I like you better as you are, dear. No one

would ever call you The Jersey Lily, perhaps—"

"Thank you," I said, somewhat stiffly. "—but still, you have your points." "Thank you again," I said, unbending a little. I leaned forward to kiss her then, but Connie turned her head aside, embarrassed.

"Not now, Pete!" she protested. "You know I don't like love-making in front of others."

"No one's looking," I said. She pointed upward at the djinn. "Don't forget him."

I looked up. He was chuckling and rumbling to himself, enjoying himself hugely. "You have only to wish that Til go away," he reminded us silkily. "I will not!" Connie said. "Now here's a pretty kettle of fish!" I said, beside myself. "Connie, if you love me—"

"I am not getting rid of the djinn!" Connie said flatly. "Why I haven't even begun to wish for anything really good yet. And I won't be rushed. After all, I'm young, with my whole life before me. I want to get used to the idea first. And, in the meantime, I'm having fun, just wishing for inconsequential things."

"But think of what you'll be missing!" I cried unthinkingly.

"Why, you conceited thing, you!" Connie said.

"It really is edifying," broke in the djinn at this point, "to meet a woman like Connie. Not a bit greedy. Not a bit mercenary. None of this wishing for money or jewels or furs or cars or sordid stuff like that."

I regarded hrm with a jaundiced eye. There were times when the djinn's stuffy smugness would have been well-nigh intolerable. But he wasn't fooling me. I knew he was just rubbing it in, laughing up his sleeve at me. He was being suavely obnoxious, skillfully doing his best to goad me into action. For he knew as well as I did that Connie would never release him of her own accord. If the djinn were to be dismissed, I'd have to do it somehow.. I didn't know how, but I'd find a way. I glanced again at the djinn and I think

WEIRD TALES

he must have been reading my mind, and sought to strengthen my resolve, for under cover of the music he whispered: "Are you man or mouse?" closing one of his eyes in a knowing wink.

And why not? Atter all, we were really allies in a way. He was as anxious to take off as I was to see him do it.

Yes, Connie, and Connie alone, was the real stumbling block. I must think of a way to alter her point of view. I must!

And musing thus, I fell into a brown study.

TTNFORTUNATELY, it was rudely in-*—' terrupted.

I don't know what brought Gloria Sbayne to that particular hotel at that particular time. I don't even want to know. I prefer to remain in ignorance of a grim and unrelenting Fate that holds these things in store for a man to tantalize him to the point of madness.

To indulge in a little ancient history, I knew Gloria when she was a show-girl, and I was press-agenting one of her shows, Let's Do It! She is blonde, with a face and a figure that are out of this world. I don't know how she does it, but put a Mother Hubbard on Gloria and she'd still manage to look like Gypsy Rose Lee just before the curtain comes down. Her personality is volatile, and she is extremely vivacious.

I could tell you, too, that she has an I. Q. of .0005, but why should I try to flatter her?

She appeared now from nowhere, and draped herself inextricably around me. "Pete Bartlett, you ole son-of-a-gun! Last time I saw you, BoBo was trying to drag you out from under her grand piano, but you wouldn't let go of Marilyn's ankle!"

"Uh," I said.

"Indeed?" Connie said, all ears.

"Uh, Gloria. This is my wife, Connie," I said, hurling myself into the breach. "We were married this morning."

"I give it a year!" cried Gloria, turning on the charm.

"Indeed?" Conoie said again.

The look she threw at me was hostile in the extreme.

"You're going to let me steal your hus* band for just one teentsy dance, aren't you, Mrs. Bartlett?" Gloria asked, without listening for an answer.

"I don't feel like dancing, Gloria," I muttered.

"Oh, go right ahead! Don't consider me!" Connie said. And she added murderously, "Petey-weetie-sweetiel"

I never realized before what an unpleasant laugh Gloria had. "Is that what she calls you! Dear God, wait'll the gang hears tli is!"

I still didn't like the glint in Connie's eyes, but I was too dazed to do anything but suffer Gloria to drag me to my tottering feet and pull me out onto the dance floor. She was talking incessantly, as usual, but it was all just a vague roaring in my ears.

Now I'm not one for making excuses for myself, as a general rule. But after all, I'd had a strenuous day. I honestly think I must have been barely conscious for the next few minutes, and that must have been why I was the last to discover the peculiar thing that happened next.

The first hint I had of anything wrong was that I noticed people were beginning to edge away from us and eye us askance. This intrigued me faintly, for my dancing isn't so bad as all that. And then, too, there seemed to be some weird metamorphosis going on under my hands.

Lightly though I'd been holding Gloria, I couldn't be uncognizant of the fact, in the beginning, that her bare back was soft and smooth to the touch. But now the fingers of my right hand were encountering strange bony protuberances. And my left hand seemed to be holding within it an eagle's talon.

I was really puzzled. But before I could draw back to look down at Gloria, she must have caught a glimpse of herself in one of the gilded mirrors adorning the walls of the room. For she started screaming like a squad-car siren.

I did look down at her then, and had all I could do to keep from ululating wildly myself.

DJINN AND BITTERS

33

That wasn't Gloria Shayne I was holding! It was a withered crone, a snaggle-toothed hag! And those bony projections I'd been feeling under my hand were the vertebrae of her bent spine.

I knew the reason for this at once, of course. I directed a glare at Connie, still sitting demurely at our table with that unseemly fog hanging low over her head.

Gloria had fainted after that one piercing scream, so I picked her up in my arms, and made my way across the dance floor to Connie.

"You know what that was?" I asked.

"What?"

"The last straw," I said. "Don't you k you've done enough damage already?"

One thing about Connie, she isn't vindictive once she has made her point. She could very well have left Gloria just as she was, a5 a lesser, more spiteful, woman would have done. But instead she said, "I wish Gloria to be returned to her natural state at once!"

And, of course, the djinn obliged. Gloria opened her eyes almost immediately, and seemed considerably bemused to find herself attractive once more.

"Good heavens!" she said. "I must have been dreaming. Though how I could have possibly been dreaming while I was dancing—"

"Pete has that effect on all women," Connie murmured.

Now Gloria may be a fool, but she isn't a damned fooi, as my Grandpa used to say. "You ask me," she said now, "there's something mighty fishy going on around here." She stood up to go.

"In the future, my dear," Connie said, bidding her good-bye, "it might be very much wiser to leave other women's husbands alone."

Gloria paled. "You did have a hand in— in whatever it was that happened to me!" She looked at me then, her brown eyes soft with pity. "I don't know what it is you've married, Pete, but you sure picked a dilly!"

"It couldn't have happened to a nicer guy," Connie agreed smoothly.

VI

WELL, I'd had all that any mortal man could be reasonably expected to stand.

"We'll go back to the cottage, Connie, right now," I said grimly. "There's a thing or two I want to talk about with you."

She could have the djinn, or she could have me. I meant to show her she couldn't have both.

Connie's eyes widened at this new note of determination in my voice. Troubled, she looked up at the djinn. He was watching me expectantly, almost encouragingly, I thought.

Connie said, "Very well."

We picked our way carefully back in the dark along the splintered, sand -strewn boards of the deserted beach walk. To our left the sea washed quietly against the shore, and the great golden moon that Connie had wished for still hung low in the sky.

It was a beautiful world, I thought sadly, but a troubled one. And here Connie and I had been frivoling the hours away with nonsense. I was ashamed. Perhaps Connie felt something of this, too, for she was very quiet.

As for the djinn, he justtrailed smckily behind us, like the wake from a funnel.

Back in the cottage once more, I asked Connie to sit in a chair. From its depth she regarded me silently while I paced the strip of carpet before her, marshalling my arguments. The djinn hovered above her, quiet too.

"Connie," I said at last, "I'm going to be very, very serious. In the months since we've known each other, I've never shown this side of myself to you before. Almost it will seem to you as if I'm stepping out of character."

She waited.

"Today," I went on, "you had something happen to you that could happen not just once in a lifetime, but once in a millennium. You were given the power to have every wish of yours gratified immediately. So far, you've just amused yourself indiscreetly, but no doubt you believe that you can ask of the

WEIRD TALES

djinn a number of things which he will immediately see that you get?"

"Of course," Connie said.

"Of course," said the djinn. "It his always been my policy to give the customer just a little bit mote than the next man." He was jesting again, but his heart wasn't in it. He too had fallen under the spell of this strangely sobered mood that was upon us.

Before I could go on, Connie said, "Peter, I want to say something. It has always been obvious to me that you considered me a mental and emotional lightweight. No, don't bother to deny it," she said, when I would have protested. "I've always known it—here." And she touched her heart. "But, Peter, perhaps I'm really not so shallow as you feared. These wishes now, need not always be for my personal gratification, as you seem to fear. I could ask for the larger things, the things of the spirit. I could ask for peace, Peter, an end of war."

She looked up at me pleadingly, begging to be understood. How I wanted to take her, then and there, into my arms! But I waited, holding myself back. Again I tried to muster my arguments.

"An end of war?" I echoed slowly. "But. Connie, after every war hasn't the world been just a little bit better? Oh, not right away, but eventually? Man has always built from destruction. He seems to learn no other way. Even the atomic age was ushered in on a wave of destruction."

CONNIE looked shocked. "But, Pete, surely you're not advocating war as a desirable thing!"

"No, of course not! But man seems to be a funny animal, Connie. He never appreciates something handed him on a silver platter. I could be wrong, but I think wishing peace for him would only be like repairing a leak in a broken hose. He'll only break out some place else. Peace is something he will have to earn for himself, or it will never mean anything to him."

"Whether that's true or not," Connie said, "let's put that question aside for the moment. There are other things. Surely I

could ask for an end of needless suffering? A cure for incurable diseases?"

"But, Connie," I objected, "you believe in some Greater Power, don't you?"

"Yes, of course."

"Then perhaps you'll concede that— It has an overall plan; that It, at least, knows i

there's a meaning to every terrible thing in life—a meaning that our small minds can't fathom?"

"Y—yes."

"Then who among us can say that any suffering is needless?"

Oh, call my arguments specious! Oil this sophistry, if you will! I was on shaky ground, and no one knew it better than I. But I was desperate, I tell you, desperate!

Before we could resume, the djinn cleared his throat apologetically.

He said, "These wishes of the spirit are beside the point anyway, I think. I shouldn't care to arrogate to myself powers that belong more properly to what Pete calls a Greater Power. After all, I am not—" He broke off, bowing his head reverently.

"You mean," Connie said, "there ate some wishes that even you could not grant?"

The djinn shrugged. "I do not know. I should not care, in any case, to put it to the test." And he said, with a cynicism that was tragic in its connotations, "Why can't you be like other humans? Contented with wishes for material things?"

For a minute, I think Connie was too shocked to answer. And then her little chin lifted stubbornly.

"Very well, then. Let's say for the moment that the djinn is right." She looked defiantly at me. "I can still wish for the material things." *

But I was ready- for that. "To what purpose?" I asked.

"But, Pete! You said yourself, only this ^

afternoon, that a million dollars wasn't silly!"

"I spoke without thought." I went on to mention the names of three of the wealthiest people in the world. "You've seen their pictures in the papers recently, Connie. With all their money, did they look like happy people to you?"

"They had the unhappiest faces I've ever

DJINN AND BITTERS

35

seen!" Connie cried. "I told you at the time I couldn't understand it."

I nodded. "The silver platter again."

"But then—" Connie began doubtfully. "Oh, Pete! You make it sound as though there were absolutely nothing in life to wish for!"

"Well, is there anything to wish for that we don't have already? Or that we can't earn for ourselves if we want it so badly?" I paused a minute, holding my breath. This was the moment. But I was on dangerous ground again, and I knew it. Everything depended on the answer Connie would make to my next question. "Connie, answer me this honestly. What were the happiest moments you've ever spent in your life?"

I waited, breath held. The djinn watched anxiously, too, sensing the crisis.

Connie didn't even have to stop to think, bless her! She smiled and said softly, "How can you ask, Pete? This afternoon, of course. On the beach. Just before I found the bottle."

I waited again, gladness now in my heart. It was the answer I'd hoped for, the answer I would have given myself had the same question been asked of me.

"Just before I found the bottle!" Connie repeated softly, her eyes widening. "And we've been squabbling ever since!" She rose then, and threw herself into my arms. "Oh,

Peter! Forgive me! We haven't been really happy since! I wish it were this afternoon again before I'd found the bottle!"

The djinn seemed to smile just before he dissolved.

The sun blazed brightly so that I was forced to squint against it, and there came the sharp salt fishy smell of the sea to sting my nostrils, and the sand was hot beneath me.

Connie raised her head from my stomach, and looked about in bewilderment. She dug furiously into the sand for a moment, but there was nothing there. She turned then, and saw me watching her with quizzical eyes.

"Sorry?" I asked.

Perhaps there was fleeting regret in her face, but only for an instant, really. "Oh, Pete! You know I'm not!"

She nuzzled her face against mine. There was no one on the beach. No hovering, eavesdropping djinn. I kissed her linger-ingly. It was wonderful. But after she caught her breath, she stared out at the sea for a long moment. And then she looked back at me.

"Just the same," she said grimly, "I will never, never, never forgive Bill Hastings for it all!"

Now I ask you!

Aren't women the darnedest?

m.

. warning, warning, warning" came the ghostly echo.

4

The ound Tower

BY

STANTON A. COBLENTZ

I

OF ALL the shocking and macabre experiences of my life, the one that I shall longest remember occurred a few years ago in Paris.

Like hundreds of other young Americans, I was then an art student in the French metropolis. Having been there several years, I had acquired a fair speaking knowledge of the language, as well as an acquaintance with many odd nooks and corners of the city, which I used to visit for my own amusement. I did not foresee that one of my strolls of discovery through the winding ancient streets was to involve me in a dread adventure.

One rather hot and sultry August evening, just as twilight was softening the hard stone outlines of the buildings, I was making a random pilgrimage through an old part of the city. I did not know just where I was; but suddenly I found myself in a district I did not remember ever having seen before. Emerging from the defile of a cra£y twisted alley, I found myself in a large stone court opposite a grim but imposing edifice.

Four or five stories high, it looked like the typical medieval fortress. Each of its

Heading by Vincent Napoli

THE ROUND TOWER

37

four corners was featured by a round tower which, with its mere slits of windows and its pointed spear-sharp peak, might have come straight from the Middle Ages. The central structure also rose to a sharp spire, surmounting all the others; its meagre windows, not quite so narrow as those of the towers, were crossed by iron bars on the two lower floors. But what most surprised me were the three successive rows of stone ramparts, each higher than the one before it, which separated me from the castle; and the musket-bearing sentries that stood in front.

"Strange," I thought, "I've never run across this place before, nor even heard it mentioned."

But curiosity is one of my dominant traits; I wouldn't have been true to my own nature if I had not started toward the castle. I will admit til at I did have a creepy sensation as I approached; something within me seemed to pull me back, as if a voice were crying, "Keep away! Keep away!" But a counter-voice—probably some devil inside me—was urging me forward.

I fully expected to be stopped by the guards; but they stood sleepily at their posts, and appeared not even to notice me. So stiff and motionless they seemed that a fleeting doubt came over me as to whether they were live men or dummies. Besides, there •was something peculiar about their uniforms; in the gathering twilight, it was hard to observe details, but their clothes seemed rather like museum pieces—almost what you would have expected of guards a hundred years ago.

Not being challenged, I kept on. I knew that it was reckless of me; but I passed through a first gate, a second, and a third, and not a hand or a voice was lifted to stop me. By the time I was in the castle itself, and saw its gray stone walls enclosing me in a sort of heavy dusk, a chill was stealing; along my spine despite the heat. A musty smell, as if from bygone centuries, was in my nostrils; and a cold sweat burst out on my brows and the palms of my hands as I turned to leave.

It was then that I first heard the voice fiom above. It was a plaintive voice, in a

woman's melodious tones. "Monsieur! Monsieur!"

"Qu'est que c'est que (a? Qu'est que c'est que $a?" I called back, almost automatically ("What is ic? What is it?").

But the chill along my spine deepened. More of that clammy sweat came out on my brow. I am sorry to own it, but I had no wish except to dash out through the three gates, past the stone ramparts, and on to the known, safe streets.

Yet within me some resisting voice cried out, "Jim. you crazy fool! What are you scared of?" And so, though shuddering, I held my ground.

"Will you come up, monsieur?" the voice invited, in the same soft feminine tones, which yet had an urgency that I could not miss. Frankness compels me to admit that there was nothing 1 desired less than to ascend those winding old stone stairs in the semi-darkness. But here was a challenge to my manliness. If I dashed away like a trembling rabbit, I'd never again be able to look myself in the face. Besides, mightn't someone really be needing my help?

WHILE my mind traveled romantically between hopes of rescuing maiden innocence and fears of being trapped into some monstrous den, I took my way slowly up the spiral stairs. Through foot-deep slits in the rock-walls, barely enough light was admitted to enable me to stumble up in a shadowy sort of way. Nevertheless, something within me still seemed to be pressing my reluctant feet forward, at the same time as a counter-force screamed that I was the world's prize fool, and would race away if I valued my skin.

That climb up the old stairway seemed never-ending, although actually I could not have mounted more than two or three flights. Once or twice, owing to some irregularity in the stone, I stumbled and almost fell. "Here, Mister, here!" the woman's voice kept encouraging. And if it hadn't been for that repeated summons, surely my courage would have given out. Even so, I noted something a little strange about the voice, the tones not quite those of the Parisian French I had learned to speak; the

WEIRD TALES

speaker apparently had a slight foreign accent.

At last, puffing a little, I found myself in a tower room—a small chamber whose round stone walls were slitted with just windows enough to make the outlines of objects mistily visible. The place was without furniture, except for a bare table and several chairs near the further wall; but what drew my attention, what held me galvanized, were the human occupants.