Chapter Three

Company Power: Making Asymmetrical Bets

Company power is the sum of all the bargaining power you can bring to bear relative to your customers, your suppliers, your sales-channel partners, and your whole-offer partners. In this context, HP under Mark Hurd dramatically increased its bargaining power, in large part by squeezing its existing businesses in order to generate returns and stock price appreciation that let it buy up additional businesses, leveraging the increase in bulk purchasing power to get better deals from suppliers, more coverage from sales-channel partners, and a bigger footprint to motivate whole-offer partners. All that bargaining power was a function of HP’s differentiation relative to its competitive set (IBM and Oracle) and relative to what each of the constituencies above values most—in HP’s case, reliable although not particularly differentiated products and services at a significantly lower price.

This is a classic operational excellence strategy for increasing company power, the sort of thing we have seen from Southwest Airlines and Wal-Mart, but not commonly from a Tier 1 enterprise IT company. It was certainly not something that IBM or Oracle was likely to copy. And that is the key to increasing company power.

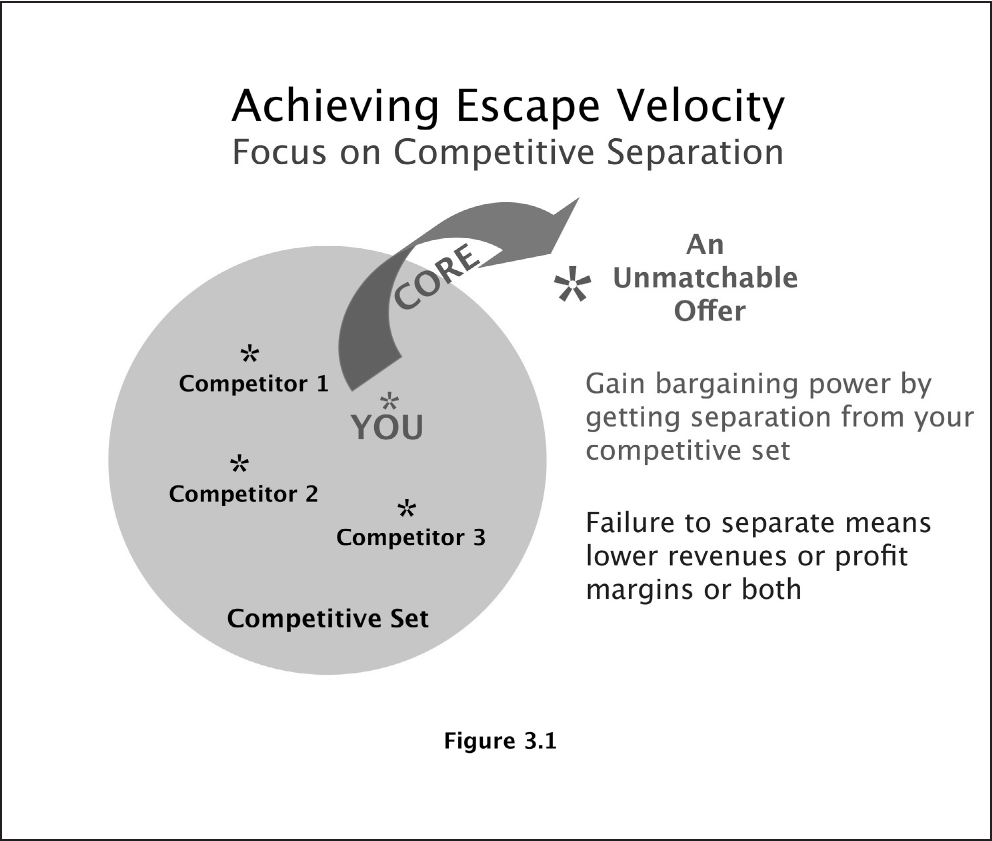

Achieving escape velocity means freeing yourself from power-deflating bake-offs with competing companies by creating one or more unmatchable offers. The path to such an outcome is illustrated by Figure 3.1.

The diagram illustrates a number of claims, each of which is critical to creating and executing a company-power strategy:

- Your company is a member of a competitive set, one that consists of you and every other company that customers and partners perceive to offer comparable, and therefore potentially substitutable, offers.

- The availability of these potential substitutes mitigates your bargaining power with customers and partners. This makes your offers harder to sell and puts revenues and profit margins under pressure.

- At the same time, however, the existence of a viable competitive set reassures customers and partners that worthwhile value is being created and that there are backup alternatives in case any given offer or vendor falls short of the mark. This makes your offers easier to buy.

- The large asterisk sitting outside the circle denotes that it is possible for one company—specifically, your company—to develop a capability that, at least for some appreciable amount of time, can generate offers unmatchable by the competitive set.

- The absence of viable substitutes increases your company’s bargaining power, making your offers easier to sell, thereby improving your revenues and profits. At the same time, because you continue to be affiliated with an established category, they also remain easy to buy. Customers are delighted and engaged; partners, on the other hand, are feeling challenged by your newfound clout. This is the optimal position for making money and maximizing returns to your shareholders.

- The arrow that leads from your current state to this highly desirable future state represents the investment and innovation required to achieve this success. The greater the force embodied in this arrow, i.e., the further from reach your novel capability is able to establish itself, the less likely that competitors will succeed—or even try—to neutralize its unique value.

- This vector of investment and innovation is your core. It is what makes you different and sets you apart from your competitive set. (Context, by contrast, is everything else you invest in to make yourself the same in order to be part of that competitive set.)

Being laser-focused about the specific direction of your core innovation investments and being Star-Trek-bold about skewing resource allocation to their specific ends together let you achieve escape velocity from your category norms. Unfortunately, most companies fall short on both counts. As a result, they live within the confines of their competitive set most of the time. Can Chrysler really set itself apart from General Motors? Can United Airlines truly differentiate from American Airlines? Is it that much better to go public with Goldman Sachs than with Morgan Stanley or Credit Suisse? Is GEICO really cheaper than State Farm? Does it have to be Pepsi—can’t it be Coke (or vice versa)? Most of the time, either one is OK, really.

But not always. Sometimes there really is no acceptable substitute. And when companies do succeed in setting themselves distinctively apart, when they do escape the gravitational field of their competitive sets, the results can be pretty spectacular, as they have been for Prius, Amazon, Apple, Google, Facebook, Cisco, and IBM. On the other hand, when they do not succeed in actually separating, it is by no means a disaster. There’s just a lot more hard work to be done to earn a much smaller reward. Ask the folks who have worked at Nissan, Borders, Palm, AskJeeves, Friendster, 3Com, or Unisys.

So what is the difference? After all, every company has a strategy to be different, and all invest heavily in R&D and marketing and operations. What ingredient is present in the few that actually do get to escape velocity? The answer, I submit, is leadership.

Now it is fashionable to believe that leaders are to be found at the top of every Fortune 500 company, but in reality the kind of leadership we are talking about here is relatively rare. It requires committing to choices that everyone else in your competitive set eschews. How smart can that be? It requires skewing resource allocation, sometimes radically, never without consternation, often over the objections of not only members of your own management team but longtime customers and partners as well. Is that really wise? It requires being willing to be wrong, sometimes dramatically and always publicly. Are you really up for that? And finally, it requires the authentic enlistment and sustained engagement of the entire management team along with the board of directors. When was the last time you got that?

Nonetheless, without this kind of breakaway leadership, there is no way to achieve escape velocity. So, wise as it may be to steer the middle course, know that it will likely bind you forever to your competitive set, allowing both customers and partners to play all of you off against one another in a perpetual effort to reduce your price and margins. Some on your team may actually be OK with this outcome, but your investors are not likely to share that view, and if they exit and the bottom-feeders come in, then you and all around you will feel the chill hand of “rationalization” and “reengineering” steering the company to a future in which you personally are not likely to play a part.

In this context, the path to escape velocity doesn’t seem so dangerous after all. And the truth is, it is not. But it does require you and your colleagues to align precisely around three key elements:

1. Your competitive set. The more precise you can be about which companies you are genuinely competing with and why, the smaller you can make the circle of competition from which you need to escape and the more likely you will be to actually escape it. The question to ask: different from whom?

2. Your core differentiation. The more precise you can be about the specific investment and innovation required to develop the unmatchable capabilities that lead to escape velocity, the more traction you will get, and the less waste you will create. The question to ask: different in what way?

3. Your execution strategy. The more precise you can be about the puts and takes needed to fund and staff your investment and innovation commitments, both in the factory and in the field, the less internal friction you create and the more alignment you enable. The question to ask: different by what means?

Getting clarity and precision around these three elements, then acting in accordance with the dictates you declare, will create company power—period. No magic is required. That said, there are subtleties to understand and pitfalls to avoid, and the rest of this chapter is devoted to instructing you in both before setting you on your way.

YOUR COMPETITIVE SET—DIFFERENT FROM WHOM?

Who exactly is in your competitive set, really? For years Scott McNealy, CEO of Sun, routinely made fun of Microsoft, contrasting it to Sun, often in very amusing if cynical ways. It made for great theater. The problem was, Microsoft was not in Sun’s competitive set—not then, not now, not ever. So this made for very expensive theater indeed.

Ask yourself, is Kia part of BMW’s competitive set? Does Wal-Mart compete with Neiman Marcus? How do you know? More important, when it comes to your company, how do you decide?

When focusing on competition, it helps to clear your mind first, for it is likely to be clogged with defensive, self-centered explanations about why your offers are better than theirs. Rest assured, on this score, nobody cares what you think. Here are some things people do care about:

- Where there is no competition, there is no market. This is why start-ups who “have no competition” have trouble engaging partners and making sales. Your competitive set is part of your overall value proposition. So choose it with care.

- You are judged by the company you keep. If you persist in talking down your competition, people will conclude you hang out with riffraff, and that will reflect on you. By contrast, if you position yourself credibly relative to worthy alternatives, that speaks well on your behalf. Dissing and differentiating are two very different activities.

- Your competitive set is the primary means by which customers and partners understand your role in the marketplace. By claiming that you can substitute for these companies, at least under certain conditions, you give them a basis for evaluating your offers. So be ambitious, but be real.

- Finally, your competitive set provides the context for understanding and valuing your differentiation, which provides a basis for tilting a purchase decision your way.

If you can put yourself in the shoes of a customer or a partner, you can construct a competitive set that will help you become more powerful even as it helps them become more successful. But you have to work within the limits of their interest in you. This calls for some pretty radical simplification, which can be achieved by paring down the field of competition in two generic ways. The first is to compete within your own business architecture; the second, to compete within your own tier. Here’s how each plays out.

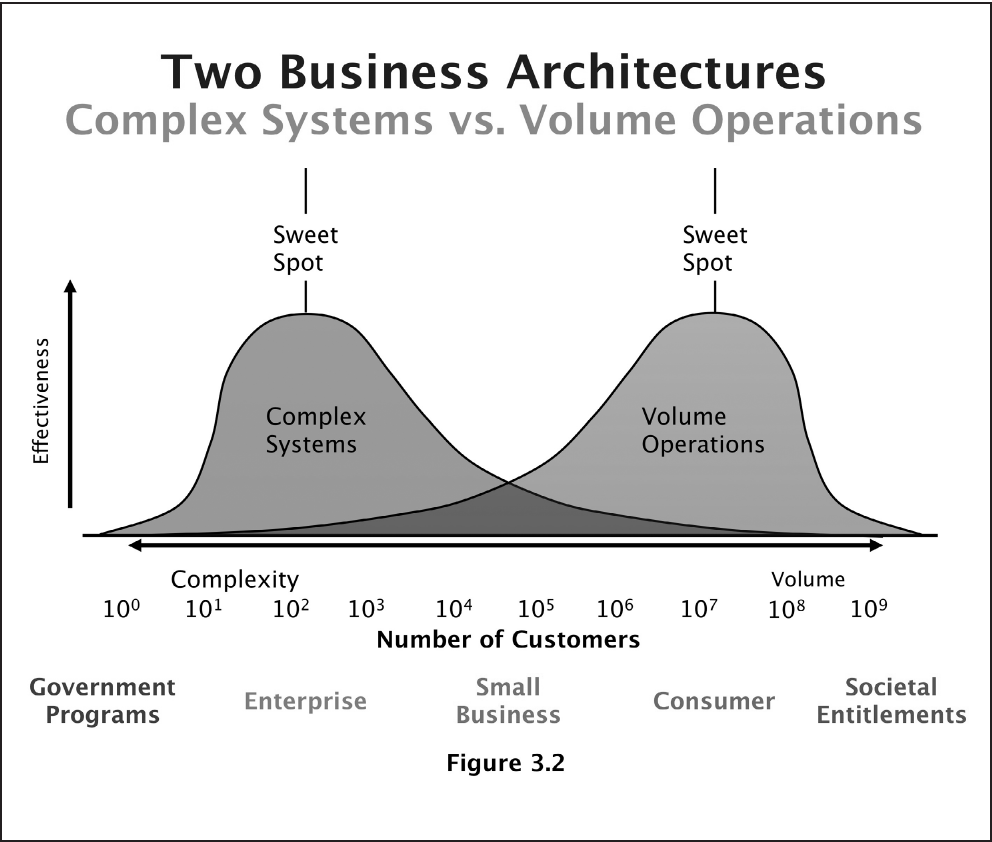

Business architecture is an idea that seems a bit abstract at first but turns out to be easy to understand in practice and surprisingly powerful. It is anchored in the observation that large successful enterprises consolidate around two—and only two—fundamental approaches to creating value, as illustrated in Figure 3.2.

1. The Complex Systems business architecture specializes in highly customized solutions to very complex challenges. Its customer lists range from government programs, of which there are typically only a few, to enterprises, of which there might be hundreds, to small businesses, of which there might be thousands. But its sweet spot is the enterprise space where it makes millions of dollars from each of hundreds of customers. Cisco, IBM, SAP, Accenture, and Oracle are all predominantly complex systems companies in this context.

2. The Volume Operations business architecture specializes in highly packaged products or service transactions that address everyday needs for large masses of people. This can range from societal entitlements that touch hundreds of millions of citizens to consumer products and services that touch tens of millions to highly standardized offers that support tens of thousands of home and small businesses. Its sweet spot is the consumer market, where it makes tens of dollars per purchase from millions of consumers on a weekly or monthly basis. Apple, Nokia, Facebook, Zynga, Sony, Twitter, and Google are all predominantly volume operations companies.

We have written at length about these two architectures, both in the Harvard Business Review (“Strategy and Your Stronger Hand,” December 2005) and in Dealing with Darwin, chapter 3. The essence of this material is that all markets self-organize around this pair of architectures, supporting a different market leader for each, the expectation being that over time the volume operations offers will encroach on the complex systems territory, eventually forcing the complex systems offers to evolve to a new level of complexity, thereby opening up the next market frontier.

In order to focus company power by restricting your competitive set, it is enough to know that customers almost never make purchase comparisons across the boundary between complex systems and volume operations. At the margin, they either want to pay up for the customization of the former or save money via the standardization of the latter. Thus if you are a large business looking for an information system, you will look to SAP or Oracle, not to Intuit or Microsoft. If you are a small business looking for computer power, you will be thinking about a PC or a Mac, not HP Linux servers or EMC storage. Small businesses have no desire to be called on by an IBM sales rep, and large businesses have no use for half-off coupons redeemable at Frys.

Your company may not be operating at either of these extremes, but at the end of the day, customers and partners need to know which of these two architectures you are ultimately committed to. The first is primarily a systems and projects affair; the second, products and transactions: which one better reflects your intent?

Whichever you choose, the clearest way to express your decision is by the companies you include in your competitive set. That is why we were so critical of Sun, a complex-systems company, calling out Microsoft, a volume-operations company, as a reference competitor. To be sure, Microsoft has systematically encroached on all Sun’s markets, but Sun’s demise was due not to that but rather to its inability to evolve to the next level of complexity. It got caught out in a no-man’s land between Microsoft and Intel coming up from the bottom, and IBM and HP coming down from the top, hoping near the end to find a third alternative business architecture in cloud computing, but not succeeding (in part validating our belief that no such third architecture exists). So it is not just customers and partners you can confuse by being muddy on this issue—it is your own employees as well.

Once you’ve privileged one architecture over the other, the second dimension of your competitive space to restrict through focus is which tier in the market you are competing in. This works something like flights in a golf tournament or ratings in amateur tennis. In the case of markets, it self-organizes into three tiers, as follows:

- Tier 1: The market leaders at the top of the heap. Think United Airlines, American Airlines, or Southwest Airlines. Think Toyota, General Motors, or Daimler AG.

- Tier 2: The other brand-name players in the game. Think Delta Airlines, Alaska Airlines, or US Airways. Think Honda, Nissan, or Audi.

- Tier 3: The remaining, largely unheralded, players in the category. Think Aloha Airlines, Air Nevada, or Freedom Air. Think Suzuki, Isuzu, or Kia.

The key point to make here is that selling partners, solution partners, suppliers, and customers self-select to focus on one of these three tiers and largely ignore the other two. Classically, Tier 1 attracts customers looking for the safe buy and willing to pay up for it, whereas Tier 3 attracts those who see the category as a commodity and are looking for the lowest price, and Tier 2 attracts those looking for something out of the ordinary, specific to their particular needs or taste, what one might call the thinking person’s choice.

While these sets may overlap at their boundaries, at their center points they are separate and distinct and do not invite comparison. That means, at any given time, while you may be indirectly competing with companies in another tier, you are directly competing only with the companies in your own. Even if you have ambitions to move up a tier, you must first create definitive competitive separation from other companies in your current tier in order to escape that tier’s gravitational field.

Now, by the time you have aligned with one of the two architectures and one of the three tiers, you have potentially achieved a six-to-one reduction in your competitive set, paring it down to the companies that people really do compare you to and you really do intend to substitute for. In this context, there is typically one company that looms as the obvious alternative to you. That company is your reference competitor by default. You may choose to embrace this pairing or to reposition yourself in relation to an alternative reference competitor, and this choice determines the core of your positioning strategy.

A reference competitor provides the foil against which you will demonstrate your strategic differentiation. Let me give a simple example from a bygone era. In the days of minicomputers and mainframes and supercomputers, a company called Convex was launching a product with dramatic new price-performance appeal. It had to make a decision as to whether to position this product as a super-minicomputer or a mini-supercomputer, and it turned out the difference between the two was profound. If it chose the former, its reference competitor would be DEC, the leader in minicomputers at the time, and its challenge would be staying ahead in R&D. If it chose the latter, its reference competitor would be Cray, the leader in supercomputing, and its challenge would be in finding big enough markets to support its growth. You can see what a difference this makes. Which partners do you most want to attract? Which customers? Which subcategory offers you the best future prospects? This is the stuff of positioning strategy. (FYI, Convex chose the latter strategy, rode it well across the chasm, got stuck in the bowling alley gutter, and was eventually acquired by HP in 1995—isn’t Wikipedia wonderful?)

Here are some more-contemporary examples. In each case, a company is targeting a reference competitor who is a worthy alternative for some applications but who serves as the perfect foil to highlight the company’s strategic positioning of its escape-velocity core:

- Cognizant, the fastest-growing global services provider over the past decade, originally chose Infosys, the leading Indian company in the category, as its reference competitor, seeking to share a common reputation for technology innovation and to differentiate based on adaptability to the customer. However, now that its revenues are fast approaching Infosys’s, the company has decided to shift its reference competitor to Accenture, signaling an intent to migrate to the highest tier in this market. Here it expects to differentiate on innovation and thought leadership, repositioning itself as a company to bring to the table much earlier in the business dialogue.

- MySpace and hi5, the number-two and number-three players in social networks, have both been forced to reposition themselves in the wake of Facebook’s global dominance of the category. There is simply no room for a second social network. MySpace, therefore, is refocusing on entertainment, specifically music, although it has yet to call out a reference competitor. And hi5 is moving into social gaming, where its reference competitor will be Zynga by default. Again, reference competitors help everyone in the ecosystem know what your company is up to, something that is particularly important when you are changing course.

- During the tech boom, Dell benefited from having first Compaq and then HP as its reference competitors, being able to share in their brand reputations for quality and reliability and being able to showcase its differentiated business model. In the past decade, however, as the industry consolidated, HP became a PC-centric reference competitor, and Dell became perceived as being stuck in a commoditizing volume-operations category. Thus in the past few years, the company has been repositioning itself to accentuate a complex-systems capability, in no small part by buying Perot Systems, and is now positioning against the complex-systems, enterprise side of the HP house. No more Dell dudes; now more Dell does.

- When Carol Bartz took over the CEO role at Yahoo!, the company was trapped in a reference competition with Google that it simply could not win. By selling off the search business to Microsoft, she was able to break this comparison and refocus the company on its media capabilities. Here her challenge is that the digital media landscape is so fragmented that Yahoo! has no direct reference competitor of merit, although Facebook may well end up filling that role, allowing Yahoo! to showcase its media aggregation assets as its core differentiation.

To sum up, we began our discussion of competitive sets with the intent of simplifying the context for communicating our strategic differentiation. But there is an additional benefit as well: it is much easier to escape the gravitational field of a tightly defined category, ideally symbolized by a single reference competitor, than to break free from a cloud of competitors who, taken collectively, can be all over the map.

Your reference competitor represents the from in a from-to arc that describes the journey of differentiation you are embarked upon. The clearer you can be about your point of embarkation, the better. Then you need to pair this from with a to, a point of arrival. What is going to be your claim to fame, the foundation of your unmatchable offer? To answer that question, you must declare your core.

DECLARING YOUR CORE—DIFFERENT IN WHAT WAY?

You want to differentiate dramatically and sustainably in order to increase your bargaining power with customers and partners so as to achieve higher revenues and greater profits. Well and good. But why would the world cooperate in helping you achieve this end, given that it will end up paying more for your offers than it does today? Normally the world is looking for cheaper, faster, better, and that goal is achieved by keeping you inside the bounds of a substitutable competitive set. Given that you want to do the opposite, how can you get the world on your side?

Well, it turns out the world does not always want cheaper, faster, better. That is what it wants as long as the category stays on its current trajectory. As long as PCs are going to be overly complex and highly demanding, I am going to want a cheaper, faster, better PC. But that is not what I really want. I really want the category to trend in a different direction altogether, as does the world, as demonstrated by its hyperenthusiastic embrace of the Apple iPad. It is a question of what you are going to put your core in service to—the status quo, in which case you must deliver better, faster, cheaper and there is little more to say about the subject, or a new trajectory, in which case you have a blank canvas upon which to paint, which does require some further commentary.

New trajectories are created by unmatchable capabilities that produce novel offerings that prove irresistible to customers. These offers are anchored in unique core competencies, as the examples in Figure 3.3 illustrate.

| Company | Core Capability | Representative Offering |

| Apple | User experience design | iPhone |

| IBM | Technical R&D | Watson |

| Rapid innovation | Android | |

| Oracle | Mature market M&A | Consolidated ERP |

| Amazon | Disruptive innovation | Elastic cloud computing |

| Pixar | Animated story-telling | Toy Story |

Figure 3.3

Each of these companies has dramatically distanced themselves from their competitive set, and by so doing has changed the very buying criteria by which customers evaluate their category.

When you undertake such an ambitious agenda, your core becomes the fulcrum upon which the category pivots. In other words, because of a unique capability that only you can provide, the category will evolve in a better way, one so deeply satisfying to the customers and partners you are targeting that they will do whatever they can to further your success. Now what in the world could be so powerful as to enable you to do that? Your crown jewels.

Crown jewels are enterprise capabilities that are valuable, defensible, and unique to your company and that, if developed and accentuated properly, create sustainable competitive advantages that enable distinctive competitive separation. The jewels metaphor is deliberately “loose” because our experience has been that these capabilities can be quite varied in nature, but here are some of the more common types:

- Technology. These jewels are almost always patented to ensure defensibility; they include Google’s search algorithms, HP’s inkjet printing, Cisco’s Internet Operating System, as well as the molecular makeup of every pharmaceutical on patent.

- Expertise. These jewels are not patentable but are both scarce and hard to acquire, often meeting the definition of trade secrets. They include the more confidential elements of Apple’s design expertise, Intel’s semiconductor process expertise, and SAP’s business process expertise, as well as Accenture’s customer domain expertise needed to focus vertical market offers effectively.

- Platform products. These are products from your company that you have made available to other vendors in your industry for the purpose of deploying their own offerings. When a company owns a proprietary platform product, it has enormous company power, like Microsoft with Windows, Oracle with the Oracle relational database, and Qualcomm with its CDMA technology.

- A passionate customer base. This is what kept Apple in the game through all the lean years and made the Grateful Dead one of the most reliable draws in entertainment history. It was what Tiger Woods lost in 2010, not coincidentally along with a huge chunk of his net worth.

- Scale. Being the biggest usually means you can be the baddest, especially when it comes to negotiating with suppliers and beating competitors on price. Wal-Mart is a long-time jewel holder here, and HP, currently the world’s largest computer company, is a newer entrant.

- Brand. In consumer markets in particular, where the noise of promotions can drown out even the best-funded marketing messages, having a recognized brand is a huge advantage, even when it needs refurbishing. Thus there is persistent value in brands like AT&T, Budweiser, Flickr, and YouTube even after they have all changed hands.

- Business model. When the world is stuck in the old way, a new way can have dramatic impact. Look at what FedEx did to package delivery, Southwest Airlines did to air travel, and more recently, what Salesforce.com is doing to enterprise software and what Mozilla is doing with browsers.

What are your crown jewels? Do you have any at all? Are they powerful enough to fulfill your company-power ambitions? Could they become so if you invested in them more deeply? These are questions that executive teams must answer collectively and unanimously in order to achieve escape velocity. The idea is not complicated, and the questions are not deceptive, but dealing with the anxieties and insecurities that they surface can be both. Nonetheless, you must get through them. Company-power strategy starts here.

Specifically, it is precisely at the intersection of what the world wants you to be and what your crown jewels can enable you to become, right where an emerging mission-critical need meets a heretofore unavailable capability, that your company’s core wants to lie. Core is the essence of company power. It is that which sets the direction of your escape trajectory. It is where you need to lead first, committing yourself to a performance that is extravagantly differentiated, and then manage second, figuring out how in the world you are going to pay for all this and still stay out of jail.

Let’s consider some current examples of companies looking to leverage their crown jewels to alter the trajectory of an established category, to the delight of their target customers and partners:

- Adobe. Computer-enabled self-service systems today are ubiquitous and becoming more so, but that does not keep them from being confusing, irritating, and unattractive. Adobe is taking its crown jewels in user experience design, rich Internet application development tools, and enterprise workflow, and putting them all in service to a new trajectory, one designed to help its enterprise customers delight their consumers rather than confound them, what the company is calling Customer Engagement Management.

- Cisco. Digital communications are proliferating like crazy, but in disconnected silos—desk phone, cell phone, text, IM, e-mail, voicemail, Web conferencing, video conferencing. What we want is for all these facilities to interoperate seamlessly—but that is not the trajectory the industry is currently on. Cisco is taking its crown jewel—the network as a platform—and putting it in service to Unified Communications under a Collaboration Architecture.

- Compuware. Because Internet applications grew up many decades after data center applications were established, the two are bolted together somewhat awkwardly, and while each domain has many tools to support it, the people responsible for managing application performance cannot readily monitor things end to end. Compuware is taking its two crown jewels, Gomez, a leading Internet monitor, with Vantage, a leading data center monitor, and welding them together to create just such an end-to-end application management platform.

These are all examples of how companies are taking advantage of crown jewels by using them to achieve escape velocity. However, they do not answer the question of how to develop the crown jewel in the first place. This requires executive teams to make highly asymmetrical bets, a topic to which we shall now turn.

COMPANY POWER THROUGH ASYMMETRICAL BETS—DIFFERENT BY WHAT MEANS?

To make a difference of the magnitude we have been describing—to bring that difference into existence and instantiate it in your company—calls for an approach we term Lead first, manage second.

Lead first means committing to a deeply asymmetrical bet on core before you allow yourself to become enmeshed in last year’s operating plan. There are a number of best practices associated with this approach, as follows:

1. Secure buy-in at the top before you launch. Let’s be clear: when it comes to making asymmetrical bets, there can be no bystanders in the game, no nonrowing passengers in the boat. If someone just cannot get behind the commitment, he or she has to be replaced, and by far the best time to do that, for everyone involved, is right at the beginning.

2. Publish the vision and the road map. This is how you declare core. The vision is not about you, it is about the new trajectory for the category, the one that will delight customers, attract partners, and inspire employees. The road map, on the other hand, is about you. It highlights the game-changing offers you intend to deliver by the grace of your crown jewels and an asymmetrical bet to capitalize upon them.

3. Burn the boats. Take the option of retreat off the table. Yes, there is a Plan B for the company but not for the current leadership team. If we fail, we all expect to be fired. Or as the ancient Greeks used to say, we will come home with our shields or on them.

4. Fund core first. Keep this effort outboard of managing business as usual by committing to it in advance. Give it precedence over everything else, and continually revisit its needs to ensure you are gaining the necessary competitive separation. For practical purposes, this means there is not one ops review, there are two—one for core and one for everything else—and they should not be mixed.

5. Use “whatever it takes” as your funding and staffing standard. The last thing you want to do is come up short on core. If you fail to gain escape velocity, you will not only have wasted an enormous amount of resources but will have incurred a huge opportunity cost as well. So once you are in, go all in. Make absolutely sure you give your core effort everything you have got. The most dangerous thing you can do is “play safe.”

6. Commit to major-market tipping points as your metric of success. The company is doing everything in its power to make this effort a success. The leaders in charge of the effort are accountable for returning a home run. Singles and doubles don’t cut it—you have to hit the ball out of the park. This means nothing less than changing the buying criteria for the category as a whole.

Steve Jobs gets tremendous credit for his leadership, as well he should (and, just to assuage your ego, he gets correspondingly low marks in management). Bill Gates, interestingly, does not always get the same high marks, but he should as well. Unlike Steve, who leads from imagination, Bill leads from a strong fact base, typically grounded in a deep understanding of a reference competitor, one he intends to overtake and obsolete, as Microsoft did to Lotus, WordPerfect, Ashton-Tate, Aldus, Novell, Apple, and Netscape—all first-tier icons in their day. Lou Gerstner led rather than managed IBM through its historic turnaround, as John Chambers led Cisco out of the dot.com bust, and Larry Ellison led Oracle through the transition from secular to cyclical growth in enterprise IT.

Management, as we shall shortly discuss, is a necessary complement to leadership, but it does not substitute for it, as the shareholders of Apple, Dell, Charles Schwab, and Starbucks learned when these companies tried—and failed—to transition the business to a management-led model. You must lead first. That means the principles outlined above trump the implied commitments entailed by last year’s operating plan. And that in turn means you need to develop a new operating plan, one that is aligned to the new core and yet still respectful of your full portfolio of obligations. No easy task, but once again, there are best practices to draw upon.

Much of the operational challenge of freeing yourself from the past consists of untangling your company from a legacy of modestly to marginally performing offers, each laying claim to just enough resource to prevent you from breaking loose. Individually they look harmless enough, but collectively they hold you hostage, robbing your enterprise of the resources needed to serve core.

How do you cut loose from these brands? Here are a few excerpts from playbooks we have seen work for our clients, several of which we will have occasion to revisit in more detail when we get to Offer Power.

1. Reorganize to foreground core. Treat the investments to achieve unmatchable core as a Horizon 2 initiative on steroids, one that engages the whole company in fast-tracking it to Horizon 1 materiality in record time. In that spirit, commit to early-adopting customers for your novel capabilities, unequivocally restricting broader distribution until the initial offers are truly game changing. Put key initiatives under a single leader, and drive to a market-validated tipping point as the critical outcome. Put all functions on notice that their first priority is to support core, and incorporate into the compensation plan metrics that reinforce this message.

2. Fund and staff your top-performing product lines 110 percent. Give them more resources in the factory, to be sure, but more important, give them more resources in the field as well. Instead of wasting time on less-competitive offers, focus your sales force on your winners, freeing them from the distraction of an underperforming but oh-so-demanding long-tail or legacy offers. You can make 100 percent of next year’s quota on the backs of your winners alone—in fact, it will be easier to make quota because you will be spending all your time on the offers the market is telling you are your best bets.

3. Ruthlessly optimize everything else. Long-tail offers are typically Horizon 1 hangers-on plus Horizon 2 failed attempts. They are not assets. They are liabilities. Manage them accordingly. To be sure, each and every one of them has champions, both inside and outside the company, so you cannot treat them in a cavalier way. But manage them you must, or else they will manage you.

4. Repurpose talent from the long tail. Do not punish people for having worked on long-tail offers. Do not discard their talents. Instead reassign them to the 110 percent product lines or challenge them to become professional optimizers of legacy long tails.

5. Recruit an outsider to break up the “web of favors.” All companies run on an internal currency of favors, a system of IOUs that middle managers have built up among themselves over the years, asking each other for help on projects and providing help when asked. These interlocking IOUs create a pervasive web of favors that institutionalizes entitlements in every nook and cranny of your business, locking in resources to low-return efforts. The only way to break through this web of favors is to install a senior executive from outside the system who unilaterally declares an end to the old debts and immediately starts a new web of favors based on implementing the journey to the new core and the long-tail rationalization needed to fund and staff it. Much unpleasantness still ensues, but there is plausible deniability for all the old-timers (“I tried to get you a pass, but they wouldn’t let me!”), and the organization will get through it, particularly once it sees some success with the new initiatives.

WRAPPING UP

As you can see, at the core of creating company power is the leadership courage to make asymmetrical bets and the management prowess to execute them in tandem with running the legacy business. These bets are always multiyear and can even be a decade long in their full sweep, certainly extending well beyond the investment horizons popular with public investors. Therefore creating company power requires that the board of directors and top management be led by the CEO to take a significant risk, for often somewhere along this journey short-term performance may fall short of expectations, your stock price will take a hit, and your company could easily be put in play. You need to decide in advance whether you are willing to take the heat for staying the course; for while winning a long-term bet outperforms a short-term orientation, sacrificing for it at the outset and then abandoning it midstream produces the worst of all possible economic returns.

In the first of two case examples that follow, the CEO inherited a company that had already been disappointing investors for some time. He and his board had to decide from the very beginning, should they grow, harvest, or liquidate? They chose to grow, and over the past decade outperformed the Nasdaq by roughly 200 percent and their reference competitor by 150 percent. Here is how they did it.

Case Example: Creating Company Power at BMC—2001 to 2010

BMC provides software to manage the data centers that host computing worldwide. Historically, this has always been a products business, wherein every different vendor’s hardware required specialized point products to manage. The reference competitor, then called Computer Associates, now called CA Technologies, had built a strong market position buying up aging companies, cutting back on next-generation R&D, harvesting their maintenance revenues, and leveraging a single worldwide sales force to sell a very broad portfolio of products.

BMC took a different approach, assembling a portfolio of best-of-breed offerings that competed effectively at the product level but did not roll up into suites. Although the company had some strong assets, notably in the IBM mainframe market, and was included in what the analysts called the Big Four of IT management software (the other three being IBM, HP, and CA), there was insufficient sales leverage in the model—no one ever bought two of anything—and at the beginning of the millennium, the company trailed CA significantly.

Bob Beauchamp took over the CEO role in 2001. Because BMC was not performing well financially at that time, his first priority was to “watertight the ship.” That turned out to be a three-year journey, but rather than defer vision for later (as Lou Gerstner famously did when taking over at IBM), right from the outset Beauchamp also articulated an escape-velocity vision for the category and the company. BMC would apply integration innovation to the category of data center management, transforming it into something he termed Business Services Management, or BSM, something that required BMC to provide end-to-end coverage for monitoring, analyzing, and remediating IT operations across a diverse landscape of vendors and devices, including the ability to prioritize IT responses based on how seriously IT problems were harming the end-users’ business operations.

This was a declaration of core. It proposed a new trajectory for the category, and it positioned BSM as a fulcrum upon which the category could pivot. It was also declared at a time when BMC was not perceived as a leader at all and frankly had only a small fraction of the software ultimately required. Indeed, this disparity was obvious enough to cause one competitor to quip, “Well, we know what the BS stands for, but we’re not sure about the M.” Nonetheless, despite the short-term inability to deliver anything like the long-term promise, BMC had declared its core and, at least internally, was navigating according to that North Star.

The impact of short-term watertight-the-ship reforms was to convert BMC’s existing book of business into a cash-generating machine, giving the company the acquisition capital necessary to pursue its long-term vision. BMC’s key departure from the norm was to forego buying up aging installed bases for their maintenance revenues and instead to acquire more-modern software assets that could contribute directly to the end-to-end architecture needed to fulfill the BSM vision. In short, M&A became a deliberate hunt for crown jewels, which came tangibly in the form of products, intangibly in the form of technology expertise and executive talent accompanying the acquisition. Because Beauchamp continued to articulate the bigger BSM vision, many of these executives stayed past their earn-outs to participate in it. At the time of this writing, the CTO, the head of sales, and the head of one of the core business units have all come to the firm originally through an acquisition.

Breakout growth, however, did not really start until the fundamental underpinnings of enterprise computing began to shift, first with the growing adoption of software as a service (SaaS) as a business model, then with the move to cloud computing as an infrastructure model. The first of these moves put heavy pressure on systems integrators like WiPro, CSC, and Infosys, who were now operating a number of data centers that they had taken over from their clients, on what one wag has called a “your mess for less” business model. They needed to get operating leverage any way they could, and one way was to run customer service applications like BMC’s Remedy in a multi-tenant way, serving many clients through the same application instance, something older software packages simply could not do.

CIOs were not exempt from the need to get operating leverage either. For example, as different IT teams would need to temporarily provision a testing platform or reserve computing capacity for a major simulation, it required enormous manual intervention to provision and tear down each instance. BMC’s BSM architecture allowed IT organizations to convert this process to a self-service, self-provisioning utility, saving all involved considerable grief.

And later in the decade, as the world shifted more and more compute cycles to a managed-hosting model, the companies providing these cloud computing services had to invest ever more deeply in utility-grade internal infrastructure. They needed, in effect, an ERP system for an IT services business. In this context, data center management software, far from playing a supporting role, became the killer app itself, and BSM’s modern end-to-end architecture was precisely the approach that fit the bill. This is what allowed BMC to distance itself so dramatically from its reference competitor in the latter half of the decade.

Even though both of these external changes were implicit in the BSM vision, it still took significant moments of leadership to get the company fully on board. In the case of supporting SaaS, a classic Horizon 2 initiative, Beauchamp appointed a GM for the business and assigned one of his top salesmen to him on a dedicated basis. The charter was to win, no matter what it took, and Bob held regularly scheduled e-staff meetings specifically in support of this effort, at which the GM was encouraged to surface any impediment to acceleration, and the e-staff commitment was to do whatever it took to quicken the new business’s pace. This was crucial to crossing the Horizon 2 chasm.

When it came to cloud computing, it was an even tougher choice, for the cloud business model actually cannibalizes the old data center model upon which the entire industry, including BMC, had been based for decades. It was critical to get the entire executive team on board with the new vision and direction, and Bob recalls a key meeting at which the head of sales, typically a champion for Horizon 1 only, said, “If we don’t get onto this new trend, we’ll all be toast in a few more years.” When everyone around the table nodded their heads, Bob jumped on that moment to reallocate resources to cloud. But then the same head of sales pointed out he could not magically improve sales productivity for the remaining resources, and thus by reducing headcount for Horizon 1, a decision that he fully supported, the company was putting short-term performance significantly at risk. So Bob froze all hiring on the spot except for quota-carrying reps for Horizon 1 business. The company did not miss its quarterly performance targets and did get through the transition successfully.

Now, at the end of the decade, for the first time, the company has an end-to-end suite that can truly deliver on its BSM promise. It’s been a long journey, one the stock market did not really twig to until the middle of the decade, and thus a very good example of the leadership fortitude and management strength necessary to execute a lead first, manage second strategy.

Case Example: Creating Company Power at Rackspace—2000 to 2010

Our second case example of creating company power is Rackspace, a service provider that hosts and manages computer services, primarily on behalf of small- to medium-sized businesses.

Computer-services hosting naturally gravitates toward being a commodity business. Customers want lower prices and standardized service-level agreements, and vendors want economies of scale from highly standardized, ideally fully automated, processes. Unfortunately, it rarely gets there. The IT industry changes too fast and the permutation of possible systems interfaces is too exponentially large to support any such outcome, except under the most draconian controls—e.g., the phone company or the cable company. For any nonmonopolistic franchise, this is not an option, so caught between an uncommoditizable service and an unavoidably commoditized price, what is a managed-hosting operator to do?

Well, at the outset of the managed-hosting boom, the conventional wisdom was to (1) charge a commodity price to accelerate growth and (2) restrict customer services as much as possible to preserve margins. This latter tactic was crucial, given a business model in which you might be charging $30 per month to balance against an average of $50 for a single customer support call, $100 if it went twenty minutes. Obviously, a policy of restricting customer service would create dissatisfaction, and churn would be high, but the conventional wisdom was that you could outgrow the churn rate, develop a valuable franchise, and fix the problem downstream.

This was the game that Rackspace was playing in 2000, when it became abundantly clear to all involved that it was not winning. Indeed, as the tech implosion began to unfold, the company found itself with ninety days’ worth of cash in the bank, bleeding cash every month, and with no realistic prospects of raising more funds. This is the definition of a “near-death experience.”

The problem, in essence, was clear to everyone: the company’s fundamental product was a losing proposition—they had to reboot, and pronto. As a result, management, led by CEO Lanham Napier, decided to jettison those losing processes, almost instantaneously, in favor of committing unequivocally to an entirely new approach to creating company power.

The new approach was based on a single principle of differentiation, to provide the very best customer service in the managed-hosting industry, bar none. This was to be the new core capability. When asked to define this new standard, one tech-support rep said, “fanatical customer support,” and the term stuck. Customer-support representatives, or Rackers, as they now were called, were expected to own and resolve the problem that spawned the contact on a whatever-it-takes basis. Period.

Not surprisingly, given the behavior of their new product, as soon as the company launched this program, customers loved it. More important, they voted with their dollars. Churn plummeted, and within 120 days, the company was profitable. From a base of 300 employees at the time of this reckoning, Rackspace has since grown to 3,300, with revenues approaching $1 billion. In short, there was a great outcome, which could be traced to a single declaration of core rolled out by a CEO-sponsored set of programs. So how exactly did the leaders do this?

First, they brought together the entire company for an open-book management session, pulling no punches, so everyone knew exactly where things stood. Then they declared that fanatical customer support was the new core, effective immediately. At the same time, they introduced a revamped hiring specification that sought out people who scored high on two key attributes—technical aptitude and desire to serve. They continued the open-book meetings monthly, so that people could see the impact of any changes. And they modified the tracking metrics to emphasize things that affected customer satisfaction, like how many times the phone rang before it was answered. Indeed, they ended up revamping their overall management system to center it on customer satisfaction, using the Net Promoter Score methodology as championed by Fred Reichheld, who not coincidentally joined their board of directors.

This was just the beginning. Shortly thereafter they instituted a “straitjacket” award for the most fanatical performance in customer support during the preceding period, as voted by one’s peers. These awards, continued to this day, are presented at company meetings, and the ceremonies often include relatives flown in from out of town, rarely leaving a dry eye in the house. And as for those monthly open-book meetings, how could you keep those going when a company has grown an order of magnitude and operates 24/7 globally? Answer: hold them three separate times during the same day, at 10 A.M., 3 P.M., and 10 P.M., so that people worldwide can hear the same story from the same people, live, just as every one of their colleagues did.

One final element of the fanatical-customer-support playbook is worth noting: strengths-based management. When you are hired into Rackspace, you take personality tests that identify your top five strengths in a portfolio of forty. From then on, Rackspace managers are charged to build on these strengths rather than try to focus on and correct your weaknesses. The amount of positive energy this releases should not be underestimated, and in a company whose strategy for core depends on people being upbeat and alert in every moment of engagement, it is nothing less than mission critical.

Overall, the truly impressive thing about Rackspace’s rise to company power is the simplicity of its approach. It really is all about fanatical customer support. By going “all in” on this vector of investment and innovation, the company had set itself apart from its competitive set and is redefining the buying criteria of the category.