Chapter Four

Market Power: Capitalizing on Markets in Transition

Market power is simply company power specific to a particular market segment. Within the segment, you are the top dog, the big fish in your pond. Indeed, market power is always best measured in terms of a fish-to-pond ratio, where a 50 percent share of new sales into the target market segment is the entry stake and 80 percent is more likely to be the sustainable steady state. In your pea patch, you are quite simply the vendor of choice.

Thus it is that Google is the worldwide category leader in search, but not in China, where the market leader is Baidu. Facebook is the worldwide category leader in social networks, but in Spanish-speaking countries it is hi5, and in Brazil it is Orkut. In each of these market segments, the worldwide leader doesn’t have a little less power—it has a lot less, as in none to speak of. Customers in each of these markets have built a fence around their local vendor of choice, and that has fundamentally altered the dynamics in the marketplace.

Market power of this kind guarantees competitive separation from your category set. When you dominate a market segment to the point that customers and partners self-organize to marginalize your competition, you have truly achieved escape velocity. And why would market segments do this? Why would they confer on your company’s exceptional bargaining power, allowing you to earn margins well above the industry standard in the global market?

The primary reason is that they want and need you to give very special attention to their particular details. Global standard products go a long way toward meeting most of the specifications for any given category, but they never go all the way to meeting all the needs. That is left either to the customer or to some intermediary. This works fine for most cases, but in some segments, some of the time, the needs are high, the specifications are demanding, and the global value chain is simply not up to the task. This creates an opening for a company to develop special products and services, often augmented by a specialized value chain, and take the segment by storm. This is the reward of niche markets.

Thus Silicon Graphics and subsequently Sun workstations took the first decade or two of business from visualization-intensive segments like oil-and-gas seismic processing, computer-aided design for semiconductors, technical publications for user manuals, industrial design for consumer products, and special-effects cinema. Thus Lecroy’s digital oscilloscope became the instrument of choice for nuclear physicists, HP’s 12C became the calculator of choice for real estate agents, and Tandem computers became the engine behind all the ATM machines that retail banking could deploy.

Now, as these examples illustrate, while niche market segments may be lucrative, they are not particularly large. This raises the question, under what circumstances does a market-segment-focused strategy make sense, and when is the cost not worth the candle?

There are at least eight situations in which a segment strategy is likely to pay for itself many times over:

1. Gaining market adoption for a disruptive technology. This is the classic crossing-the-chasm scenario, wherein the goal is to accelerate mainstream acceptance of a disruptive next-generation technology by first winning over a beachhead segment, the way Lotus Notes won over global consulting, cellular telephony won over financial services, and networked attached storage won over high-tech engineering.

2. Penetrating a new geography. Regardless of how strong you are elsewhere around the globe, a new geography represents a new hill to climb. Just ask Google about its adventures in China or Nokia about its experiences in the U.S. market. Targeting an underserved segment, meeting its end-to-end needs all the way, is a great way to get market insiders pulling you in. Once you get a beachhead in the new geography, once you have a strong reference base among some constituency, then you are positioned to grow forward. This is the “land and expand” strategy as played by complex-systems vendors.

3. Getting out from behind the market leader. We have all heard the saying, When you’re not the lead dog, the view never changes. But how do you get out from behind a number one? You need to pull into an adjacent lane to pass. Underserved market segments provide just the opportunity. When these markets finally do commit to a vendor, their spending rate dramatically outperforms the market as a whole, giving your franchise a boost. You still have work to do to overtake number one, but you are no longer breathing its exhaust.

4. Anchoring a turnaround. When your company is on the ropes, you need a “can’t miss” market victory upon which to pivot to recovery. There is nothing like a niche market segment for solving this problem. Regardless of the size or fitness of your fish, there is always a pond in which you can make yourself the dominant species and then nurse yourself back to health. Look at how the Mac faithful kept an on-the-ropes Apple in the game during its dark years. Look at how Public Safety is keeping Motorola’s network franchise viable during its tough times.

5. Solving for the “stuck in neutral” problem. This is somewhat like a turnaround but actually harder to execute, because you do not have the energizing impact of a “near-death experience” to galvanize the troops. Tier 2 vendors, in particular, have a tough time energizing anyone—their customers, their partners, or their employees. Everyone tends to take their existence for granted, but no one is disposed to pay a price premium for their offerings. This portends a slow but steady slide into commoditization, acquisition, and dissolution. At any point on this decay curve, however, a management team can retake control of its destiny by targeting a niche market segment in need and becoming its favorite candidate. Win any primary, and you have delegate votes during the nominating convention. Come in middle of the pack, and you have none.

6. Capitalizing on a great niche opportunity. Let’s not forget, there are some great niche markets out there that any company, big or small, would like to have a leadership position in, pretty much at any time: pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, investment banking, oil and gas, automotive, health care delivery, and the like. These are highly concentrated markets where a handful of companies spend a boatload of capital on next-generation facilities and tools. The barriers to entry are high, as are the barriers to exit once you get installed, so you can build high-value sustainable franchises without ever leaving the niche. Ask Cerner about health care, ask Schlumberger about oil and gas, ask Sungard about financial services.

7. Exploiting the “granularity of growth.” As Mehrdad Baghai has taught us in his book The Granularity of Growth, when markets mature and commoditize, value migrates from the core offer to the secondary elements surrounding it—test and measurement instruments for food safety in China; secure, rugged mobile computers for personnel in field service and delivery; video security to prevent shoplifting in checkout lines. Profit pools migrate to those niche segments that are more than willing to pay a premium to get their particular preferences met, and thus growth, as measured by revenue and earnings as opposed to units shipped, comes more and more from microcampaigns focusing specifically on opportunities like these.

8. Capitalizing on a market in transition. Here an entire segment’s infrastructure is being disrupted, and every company in the segment is looking for a safe haven that is compatible with the new world order. At the time of this writing, media and entertainment, risk management in financial services, call centers for consumer services, consumer advertising, and travel and hospitality are all markets in transition, all caught in a painful bind between legacy systems that are falling into disuse and next-generation systems that do not yet deliver the goods. The first whole-offer teams to arrive at their doorsteps with true end-to-end solutions to their problems will delight them so much they will want to marry them. And despite the confines of a niche market, wholesale infrastructure replacement is sufficiently lucrative that even the largest market leader should take an interest.

These are all reasons why you would want to adopt a market-power strategy. But you need to keep in mind some limiting factors, as well. Market-power development does not pay off in its first year. It does pay off reasonably well in its second year and quite handsomely in the third, as long as you have a financial runway and the patience and discipline to stay the course.

Second, market power plays a much bigger role in a complex-systems franchise than a volume-operations one. That’s because the former can readily develop niche-specific whole offers through the use of custom services, can modulate price points up and down on a case-by-case basis, can build high barriers to entry and to exit, and can be cash-flow positive throughout. A volume-operations business cannot make money at low volumes, cannot readily supplement its offers with services, cannot modulate price points, and so needs much more of a winner-take-all model.

Third, while these strategies are quite good for generating tens of millions of dollars of revenue for complex-systems companies, they do not normally generate hundreds of millions. Even when you include entry into adjacent segments, it is hard to see any niche-based strategy adding up to a billion dollars. Most level out below a half billion. That’s fine for a company going through its first growth spurt, and even fine for a company of several billion in size looking to supplement its portfolio, but it is subscale for the top end of the Fortune 500. There you’re more likely to use market power in conjunction with company power to build a combined strategy of organic growth complemented with one or more major acquisitions.

And finally, market-power strategies require specialized talent to execute, including some key players who are not currently on your bench at all. Whenever a generalist has to recruit a specialist, there is always risk, especially when both the level you hire at and the amount of empowerment you confer on the new hire are likely to raise eyebrows elsewhere in your firm. It is critical, therefore, to get buy-in to the need for market power prior to spending this kind of personal capital.

To navigate these trade-offs, we have developed three core rules for gaining maximum returns from targeting a market segment:

1. Big enough to matter. When you win leading market share in the segment, say anything over 40 percent, that amount of revenue has to be material to your enterprise’s total performance—ideally 10 percent or more of total revenues. So do that math. If you are a $100 million enterprise, market segments are a great way to double your size. That was how Documentum grew from $35 million to $350 million. If you are a $1 billion enterprise, you are pushing the limits of market-segment strategy, although you would still use it to cross the chasm with a disruptive innovation, as Sybase did with its analytics database server, taking it first to Wall Street, then to the database market at large.

2. Small enough to lead. This is the fish-to-pond ratio part of the math exercise. If the segment is already several hundred million and you are a new entrant, this is typically a nonstarter, although you can often carve off a high-growth subsegment and focus just there. This is how RIM was able to enter the PDA market, by focusing on mobile enterprise e-mail users as virtually their sole segment.

3. Good fit with your crown jewels. This allows you to take the segment by storm because, in addition to bringing focus to the party, you bring some unique capability that simply blows your target customer away. Gyration, a company with miniaturized gyroscope technology that was eventually acquired by Thomson Consumer Electronics, dominated the professional presentation market for mobile mice because you could control the screen with hand gestures. It was a small market, but big enough to matter to Gyration at the time, serving as a stepping-stone for their entry into the broader market for wireless mice and gestural remote controls.

Sticking with these three rules will help you target the right kind of opportunities. After that, you have to execute on them. That leads us to a playbook for creating market power, which we call target market initiatives.

CREATING MARKET POWER: TARGET MARKET INITIATIVES

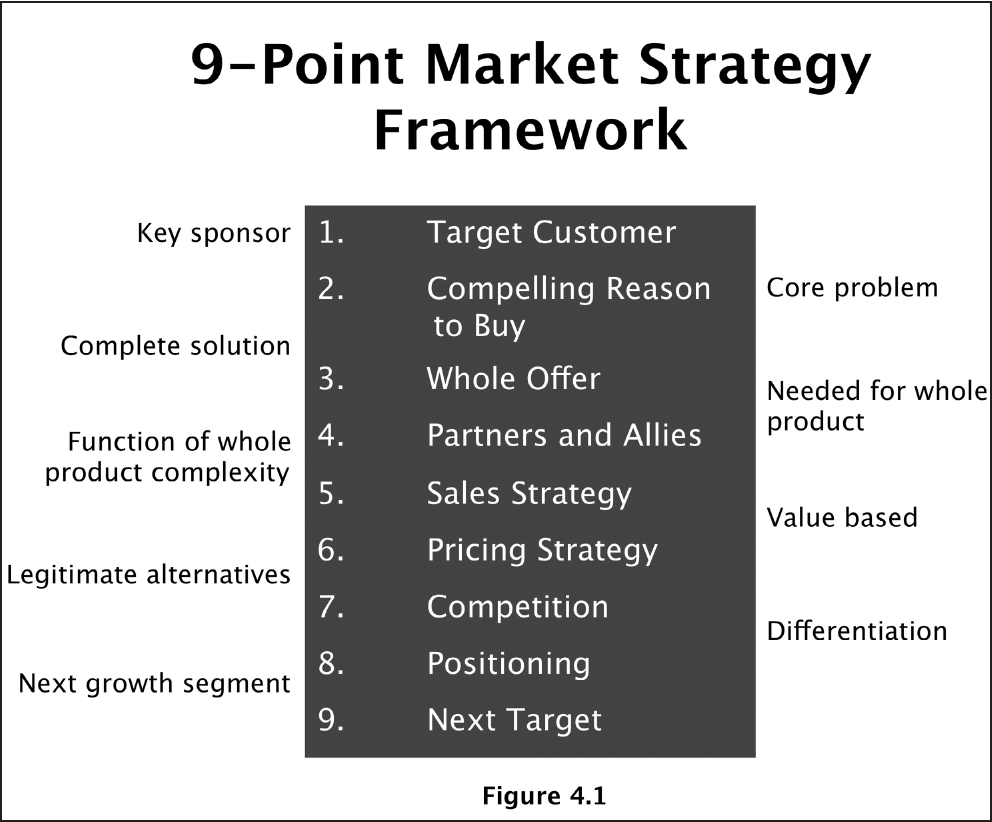

Target market initiatives (or TMIs, for short) are multiquarter, multiyear efforts to win dominant market share in a target market segment. They are developed around a sequence of tactics captured in a nine-point checklist (see Figure 4.1).

This list represents the table of contents for a playbook primarily targeted at complex-systems vendors, one we have been helping our clients run for over twenty years. It is anchored in the notion that market segments are word-of-mouth communities that reference each other when making purchase decisions. The goal of the playbook is to orchestrate a tipping point in your target market, after which word of mouth among customers, partners, and third parties endorses both the need to adopt a new solution and also the claim that your company is the preferred source. Once that tipping point is reached, the market actually comes to you voluntarily, dramatically reducing your marketing and sales costs while increasing your bargaining power. This is a beautiful thing.

The strategy works for all eight of the scenarios previously highlighted, but it creates the greatest returns for established enterprises when applied to scenario number 8, capitalizing on a market in transition. Here the shift in spending happens so quickly that the anointed vendor—rarely an incumbent—seems to come out of nowhere to decimate the competition. This creates an aura of invincibility around the new offer that can carry over into other markets, even ones not adjacent to the target market, as witnessed by Apple’s iPad, clearly a consumer product, having a revolutionary impact on mobile end points for enterprise IT. And so as we walk through the nine-point model, we will be using markets in transition as our anchor case.

TARGET CUSTOMER AND COMPELLING REASON TO BUY

Our journey begins by targeting a single market in transition, one segment out of many, and it is right here at the beginning, as often as not, that management teams go astray. It turns out that the concept of market segment is a very slippery fish. Different constituencies in your enterprise and ecosystem use the term in very different ways, the net of which is that most segment-based strategies don’t achieve the focus necessary to win. Here’s what’s going on:

- Sales professionals use the term market segment in the context of defining sales coverage and sales territories. In this usage, prospects are segmented primarily by size and by location, leading to coverage assignments like global accounts, major accounts, and indirect-channel accounts, which are further subdivided geographically into regions like New York, southeastern United States, Germany, or EMEA (Europe, the Middle East, and Africa).

Such taxonomies are useful for sorting out coverage responsibilities and commission entitlements, but they have no value for TMIs. That is because they do not align with the social structures that establish word-of-mouth communication boundaries. The key to tipping-point strategies is for prospects to hear the same message from three or four different sources, all from within their own community. “Major accounts in the Southeast” does not equate to a community—it is a bounded set only in the minds of a sales team. Thus sales territories are almost always a distraction for TMI strategies. Indeed, TMI strategies frequently play havoc with sales territories.

- A second way to segment markets is by subcategory. This is how industry analysts like Forrester and the Gartner Group track market share. They segment the PC category into the server market, the desktop market, the laptop market, each of which is a subcategory of PC. Similarly, Consumer Reports or J.D. Powers might segment the automobile category into luxury sedans, economy cars, trucks, SUVs, and the like.

Shares of subcategories are highly useful metrics for calibrating company power, but they are not useful for market power. Again that is because they do not align directly with the social structure of word-of-mouth communities, the critical transmitter of market-segment leadership perception. Just because you own a laptop or drive an SUV doesn’t mean you participate in a community of like-minded individuals.

So then how do communities align? In a word, socially. Specifically, in the social structure of business-to-business complex-systems markets, they align by industry, profession, and geography. That is:

- Executives in the entertainment industry all know or know of each other, to a much greater extent than they know executives in the automotive industry.

- Chief financial officers typically know peers in their profession across many different industries, as they often compete for each other’s jobs.

- And people who live in the geographies of England, Japan, and France show a strong preference to interact with other people who live there, and not coincidentally speak English or Japanese or French—go figure!

For a strong TMI effect, you really want all three clicking together. U.S.-located English-speaking CFOs in the entertainment industry—now there’s a tight word-of-mouth community. To be fair, you can “cheat” on this model by relaxing one of these three dimensions—typically industry—and still create segment power, say, around sales organizations in the United States (Salesforce.com), HR professionals in the United States (PeopleSoft), global consultancies beginning with the United States and EMEA (Lotus Notes), and the like. Also, in highly concentrated industries, you can often relax the geography standard, as in pharmaceuticals, oil and gas, and aerospace and defense, all of which transcend geographical dispersal.

This kind of “flexing” of the model creates headroom for very large corporations, which really need to find a way to exercise their global reach in order to be fully competitive and to reach materiality within an acceptable time frame. By contrast, the smaller you are, the more important it is to tighten your focus, because it is this very tightening of market dimensions that keeps the bigger fish out of your pond.

Finally, there is one other dimension of the concept of market segment that can still derail your efforts before they even get started—the false notion that segments have firm and fixed boundaries. To be sure, people actually know there are no fixed boundaries in the real world, but the execution mechanics of sales-territory assignment, sales compensation programs, and lead-generation marketing all conspire to drive organizations to simplify the concept.

This would be fine, except that sales teams are inherently interested in increasing the size of their territories and will focus incessantly on opportunities at or just beyond the edges of their pea patch. This leads to way too much time, talent, and management attention getting focused on borderline cases. You end up bickering over boundaries, all the while losing precious time in capturing the really key accounts in the segment.

So to head this problem off at the outset, point out to everyone involved that while social group boundaries are inherently fuzzy at the edges, social groups do have distinct and persistent centers. The center point of any target market segment is the “perfect target customer,” the poster child for that segment, the pure embodiment of the type of company, people, and problems that characterize that set.

So to communicate market focus, simply build a core use case around a day in the life of your poster child, then say to marketing, “Get us in touch with people like that,” and to sales, “Bring me deals that look like that,” and to engineering, “Create solutions for use cases like this one,” and to professional services, “Get smart about how we can help customers solve this sort of problem.”

All this brings us back to the number-one item on the TMI checklist: the target customer. In a volume-operations market, the target customer is usually one person who may or may not be buying for another person, say a spouse or child. But in a complex-systems market, there are multiple people who must approve a single purchase order, thereby turning the target customer into a hydra-headed beast. These include the budget creator (typically a line-of-business executive), the budget release monitor (typically a controller or other financial executive), the use-case sponsor (typically a department manager, to whom the use-case users report), and a specialist team that will actually take title to the purchase and support its use (typically the IT department in the industries we consult to), not to mention the ever-present purchasing department riding herd on the terms and conditions of the deal, especially price.

So who really is the target customer, specifically in a TMI, and even more specifically when targeting a market in transition? The answer is the department manager with the problem use case, backed by the financial support of the line-of-business executive to whom that department reports. Here’s why.

TMIs are about addressing unsolved problems. That means there is no budget specifically allocated to the solution, because no solution has yet emerged. But there is budget being spent on remediating the problem. That budget is coming out of the line-of-business executive’s P&L and is being spent by the department manager who owns the problem process. Everyone acknowledges this is an unproductive use of funds, but in the absence of a viable solution, what else can you do?

Companies in this state have a compelling reason to buy¸ as the following examples will illustrate:

- Risk managers in investment banks trading on their own accounts who cannot accurately assess the bank’s total risk position.

- Print publishers watching their circulation dwindle under the pressure of digital media.

- Health care providers whose emergency rooms have become holding areas for health services to the uninsured.

- Pharmaceutical R&D executives watching the deterioration of the industry’s blockbuster drug model and the escalating costs of in-house R&D.

- Licensed software package vendors watching market share shift toward software-as-a-service business models.

- Advertising agencies watching the deterioration of media buying as an overall funding vehicle for value-added services.

- Buy-side investors faced with a dearth of independent investment advice and analysis, now that these functions can no longer be subsidized by the sell side.

In every case, there is standard infrastructure in place that does not really meet the needs of the situation. The infrastructure team is not equipped to close the gap, so the performance of the department in question is deteriorating, increasing the risk that it will jeopardize the performance of the organization as a whole. The line-of-business executive is under pressure to fix this and, most important, has resources already committed to addressing the problem—just in a very inefficient way. The department manager is under pressure to come up with a better solution.

Given all this, you can see why a well targeted TMI, especially one targeted at a market in transition, has such a great chance for success. At minimum, you will definitely get a hearing, initially with the department manager, and if you pass that hurdle, then with the line-of-business executive (or vice versa—either path works). And the ask is, try us out, and if you find we are the real deal, then redirect your current spend away from Band-Aiding stopgaps and invest in a real solution instead.

That real solution is what we call the whole offer.

THE WHOLE OFFER AND PARTNERS AND ALLIES

To capitalize on a market in transition, you have to be first to arrive with a true solution to the problem at hand, or what legendary marketing professor Ted Levitt and high-tech marketing pioneer Bill Davidow taught us to call the whole product. Subsequently we have taken to calling this the whole offer, as it applies just as well to service providers as to product vendors. And because this will be an end-to-end solution to a relatively complex problem, it will typically incorporate elements coming from companies other than yours, hence the pairing of whole offer with partners and allies.

The key tactic for swift TMI success is to make a preemptive strike—committing to something the competition either cannot or will not match—and leverage early wins to create an insurmountable lead. When that occurs, the word goes out that you are both the real deal and the safe buy, and prospects begin to give your competitors a much tougher time, often leading the latter’s sales teams to turn elsewhere in search of greener pastures.

The perfect preemptive strike is a whole offer, ready to go, that gets right to the heart of the problem. To have such a thing at the outset of your campaign, however, is quite a stretch. You’re much more likely to have a decent start and an insight or two that put you slightly ahead of the pack. How do you get to a preemptive punch from there?

Two key actions are required. The first is to hire a senior executive out of the target industry who is deeply familiar with the customer’s business problem and passionate about solving it. Sometimes this person can actually be an early-adopting customer for your offer, someone who is more excited about evangelizing it than staying in his or her current role. This person performs two critical functions. The first is to help you focus your whole-offer efforts precisely on the target customer’s compelling reason to buy, and the second is to leverage his or her prior business relationships to connect you to the line-of-business executives for budget and project sponsorship. People in this role also help the professional-services team prioritize which elements of the customer problem to take on in which order, as well as help the product team identify potential crown jewels to differentiate your solution.

The second action you must take early in the game is to isolate and feature a crown jewel at the heart of your solution architecture, something no other competitor has. Your sales team can redefine the entire basis of the sales competition by throwing this jewel down like a gauntlet and challenging the competition to match it. Let me give a small example.

In the early 1990s, right at the outset of the client-server software era, little Lawson Software, at the time a $40 million ERP application software company from Minneapolis, had to take on Oracle, SAP, and PeopleSoft. There was no way it could go head to head with these behemoths. It had to find a smaller pond within which it could grow to a bigger fish. To do so it targeted health care institutions, particularly ones called integrated delivery networks, or IDNs, and focused on attacking the problem of health care cost reduction through better materials management. This was at the outset of the Clinton administration, when health care cost reform was very much in the air, and poor materials management was a broken mission-critical process.

Now every ERP system has a materials management module, so how was Lawson to set itself apart? Well it turns out that hospitals stage their medical inventory on a par cart, a mobile unit that can be wheeled from one operating theater to another and that needs to be fully stocked at all times. This led to a lot of “just in case” duplication of inventory as opposed to a more efficient “just in time” replacement strategy. However, no other industry uses a par cart approach to inventory management, so naturally no ERP system supported it.

Lawson jumped into the breach. It quickly cobbled together a demo of par cart inventory management and promised to ship a working version in its next release. It accelerated that release, creating a separate branch of development focused on integrating the par cart capability. Its customer presentation focused on par cart–based inventory management as the key to solving the materials management challenge. And it provided extra on-site project support to get its first few customers up to speed.

The preemptive strike worked. Lawson became the segment leader, getting featured treatment at health care trade shows and solicitations from big systems integrators who wanted to expand their health care offerings with materials management. Sales forces from far bigger, more established software companies simply worked around Lawson as best they could or pursued other opportunities. The company grew an order of magnitude in the space of six years and went public, all achieved on a bedrock performance in health care.

Part of Lawson’s success was partner success as well. Every installation was not only an opportunity for a systems integrator to make money but also a chance to build a relationship with executives in a market in transition. Before Lawson had the inside track, partners would give the company lip service but had no real stake in its success. But once it became the segment leader, the bandwagon effect unfolded.

There is a key lesson here: before there is a viable market, do not look to partners for much help. Your unproven bet represents a substantial opportunity cost for them, and until the odds are stacked more in your favor, this is a bad bet for them to make. If at the very outset you really do need a deep partner commitment to complete your whole offer, then target a second-tier player looking for a chance to break into the top tier, and build up the size of their reward by committing to do everything you can to get them into your deals, effectively offering them a “virtual exclusive” in return for their early support.

For the most part, however, you have to rely on professional services from your own company to drive the first few projects and backfill the gaps in the nascent whole offer. This is, in effect, a Horizon 2 effort, meaning you have to adjust organization and metrics to get the support the TMI needs. But once you get past the tipping point, you can either recruit partners to handle the repeatable solution elements or monetize professional services in what has now become a Horizon 1 opportunity.

SALES STRATEGY AND PRICING STRATEGY

The sales strategy needed to exploit a market in transition is a cut above traditional solution selling. The latter qualifies a prospect based on whether or not there is budget in place and a commitment to engage. At the outset of a market in transition, there is frequently neither. Now what?

My colleagues Philip Lay and Todd Hewlin and I addressed this challenge in our March 2009 Harvard Business Review article entitled, “In a Downturn, Provoke Your Customers.” The principles we outlined apply equally well to preempting segment leadership in a market in transition. They include the following:

- Identify a business process and underlying system that the market transition is stressing to the breaking point.

- Call attention to the severity of the consequences of not addressing this situation immediately as well as to the improbability of conventional approaches being able to solve this problem long-term.

- Propose a dramatically different approach, one that involves shifting investment priorities and budget allocation from short-term remedial efforts to a viable long-term solution.

- Win executive sponsorship for a brief, highly focused services engagement to determine the feasibility and value of the proposed new approach.

- Based on the output of that engagement, propose an end-to-end solution to be funded by budget reallocation sponsored by the business process owner.

As you can see from the bullet points above, this is a far cry from everyday solution selling. In particular, it involves calling much higher in the prospect organization than normal and bringing to bear a more deeply informed point of view than is normally practical to develop. Both these responsibilities fall on the field marketing organization, which must adopt a practice we call referral-based marketing.

In referral-based marketing, you do not prospect for leads in the traditional sense of the term. That is because in a market in transition, people do not as yet have projects funded, so there are no leads per se. Instead, you must target “plausible suspects,” specifically in the thirty to forty most influential corporations in the market segment under transition. Winning projects in five to eight of these over the next four to six quarters will create the word-of-mouth tipping point you are looking for.

Within each of these targeted firms, your marketing team must identify the line-of-business executive most likely to be responsible for the broken mission-critical business process you’ve targeted; then your team must figure out a path of referral that can get someone in your company a meeting with that person. The meeting’s stated purpose is to discuss your company’s next-generation thinking about the impending problems hitting that prospective customer’s industry.

Another part of marketing’s job is to capture that next-generation thinking in a succinct form and to orchestrate the referral process that gets you the meeting. Sales’s job is to conduct the meeting, typically by bringing a very senior executive from your company to present your views. But this is not a sales call. You are not trying to get an order. Instead, you are trying to recruit a senior executive to sponsor taking a novel approach to a troubling problem, funding the effort by redirecting current spend away from its present uses. Typically the best person to conduct this conversation is the one you have recruited out of the target segment. And the objective of this first meeting is simply to close, or to get as next to closure as possible, on a commitment to coexplore the feasibility of your proposed approach.

All in all, this is a pretty big ask of marketing, particularly if you have built an organization focused on traditional lead generation in mature, cyclical growth categories. But there is a wonderful way to increase the odds of success considerably. It harks back to when you were first testing your whole-offer concept for the end-to-end solution, months before you were ready to actually go to market with it.

At that time, your marketing team was asked to help determine how compelling was the target customer’s reason to buy and how competitive was your proposed whole offer relative to the status quo. In so doing, instead of reaching out to industry analysts (who would not be focused on this issue as there is not yet a market under way), they were encouraged to reach out to the same thirty to forty companies that are now your sales targets. So in reality you already have beachhead contacts to work.

To be sure, the marketing team ended up calling much lower in the organization than you will, and they were asking much humbler questions, with the goal of getting as much customer input as possible to help shape the future whole-offer release. But in so doing, they inevitably gathered intelligence about the specific target company, and they almost always secured an invitation to come back and present the whole offer once it was ready. As a result, getting the desired appointment is not quite as challenging as it might at first seem, as you can put on the table specific pain points that are far from randomly selected.

All of this customization comes at a price, of course, which brings us to the topic of pricing strategy and its role in winning share during a market transition. Solution-based pricing is inherently value based, the returns to the customer being a function of the cost reduction and risk reduction gained from meeting a highly problematic challenge head-on. This value can often be an order of magnitude greater than the direct costs of the offering, and so discounting is normally neither required nor desirable.

For example, Autodesk is currently developing the market for 3-D simulation software for the construction of buildings. Architects have used this for years, but the company is now focusing on contractors and building owners, the value proposition being to detect and head off project-delaying disconnects among the various subsystems and subcontractors that must come together to create a complex structure. In this context consider the cost of overrunning a major construction project even one day. Compare that to what you could spend on software to prevent this outcome. The gap is so great, it becomes a no-brainer to buy, provided the whole offer really does what the vendor is promising. Pricing in such a case should never be the issue.

If, on the other hand, you discover in your TMI that price has indeed become a significant issue, it usually means you are making a mistake, typically of the following sort:

1. Talking to someone who cannot reallocate budget and therefore has to squeeze money out of existing allocations, or

2. Addressing an issue that is not as compelling as you think it is, or

3. Proposing a whole offer that either is not credible or does not properly fit the problem at hand.

Discounting price is a poor response to any of these concerns. Instead, when it comes to pricing strategies for winning market power, focus your thinking on whole-offer pricing, meaning the end-to-end cost to the target customer all in—that is, what is paid to you and to your partners, and what is spent internally to put the complete solution in place. Make sure this total number is consistent with all of the following:

1. The budget reallocation capability of the line-of-business executive sponsor (to be compelling, the whole-offer price must be significantly less than the current remediation spend);

2. The overall value to the customer, including time to break even on the investment (because there is always competition for funds within any organization);

3. The business interests of the partners or allies who must contribute to the whole offer (you want to make sure there is enough money here for them, or else they will not come to your party); and

4. The compensation system of the sales agents responsible for selling the whole offer (so that it is worth their while to spend their time, talent, and management attention on your offer instead of on whatever else is in their bag).

Consider the example of Documentum, which led the adoption of computerized document management in the pharmaceutical industry, focusing initially on massive New Drug Approval submissions to the FDA, sometimes exceeding 500,000 pages. The target customer was the government-affairs department in each of the top forty pharmaceutical companies. But that department had no budget for the several-million-dollar expense of the total solution. So Documentum had to make its case instead to the line-of-business executives accountable for revenue from drugs under development. Its argument was simple: A patented drug averages $400 million a year in revenue (this was in 1992), or about $1 million per day. Currently it is taking your manual document-management processes anywhere from six months to a year to assemble a fully quality-checked FDA submission. That’s $200 to $400 million in lost revenue. Our system, we believe, can do it in six weeks and costs $2 to $3 million. Are there any questions?

Of course, there were. But the value proposition was so compelling that pricing was rarely an issue—as long as the budget was being sponsored by a revenue-generating entity. When there were hiccups, invariably it was because a cost center—either the government-affairs department or the IT organization—was trying to sponsor the project without sufficient line-of-business support.

Assuming you have success in dealing with all of the above, it is important that you, too, get your fair share of the whole-offer price. This will cover a blend of product and service and maybe even a little R&D, as well. It is important to keep this mix opaque to the marketplace, because that helps establish a value-based reference point that can support relatively high margins even after the R&D work is done and the service demands have been curtailed. These high margins are part of the higher returns necessary to warrant your undertaking market development risk in the first place.

COMPETITION AND POSITIONING

One of the rewards for attacking a market in transition is that there is no entrenched competition to overcome. Instead the competitive landscape is divided into two camps. On the one hand, you have the incumbent vendors, who have established relationships with the target company but whose offerings cannot meet the challenges of the transition; and on the other hand, you have new entrants like you, who may be able to solve these next-generation problems but do not have executive relationships or domain expertise in the target market’s business processes. The market is stalled because neither alternative is sufficient to move it out of stasis.

You would think the incumbents would have the advantage here, but they are actually somewhat poorly positioned. True, their relationships are long-standing, but over the years they have drifted down from the executive suite and now reside among the systems managers and technical specialists directly responsible for maintaining the systems they sell. This is not a population eager to adopt change. The pending market transition is putting both their job performance and job security under assault, and the last thing the people on this team want to do is draw attention to themselves.

New vendors like you are at least not tainted with the systemic failures that have led to the current set of broken mission-critical business processes. This is a positioning advantage. Moreover, because you represent a fresh point of view, the line-of-business executive on the hot seat is more than open to hearing your story. But because he or she is not a technology expert, your story has to be told, at least initially, in the business language of the problems and not in the technical language of the solution.

To meet this positioning challenge, it is critical that you incorporate into your team a domain expert who is fully versed in the language and processes of the target market. His or her job is to help you get the broken process clearly in view, help you understand why the installed systems cannot possibly address the challenge at hand (usually they are part of the problem), and help you craft a credible whole offer that leverages your crown jewels to solve the problem.

Having helped craft the solution, these same people are crucial to helping position it. Because they come out of the industry you are seeking to go into, they are often familiar with the incumbent solution vendors and thus able to give them their due while still pointing out their inability to address the specific challenge at hand. And because you have recruited them into your company, they are now familiar enough with your offering to explain how it is different and why it is game changing. Leveraging all these advantages, their positioning task is first to project a credible vision for a future state in which the problem is solved and then to describe a realistic path for getting there.

In sum, your positioning is anchored in:

- Your understanding of the problem,

- The crown jewels that let you approach that problem from a new angle, and

- Your appreciation for the details and complexities of changing from the current to the future state.

Note, in particular, that positioning messages in general are not about you or your products. TMI messages are all about being in service to solving a very tough problem. It is the problem, first and foremost, that binds you to the customer, and the more you have focused your communication in dialogues about the problem—as opposed to your solution—the more powerful your position will be.

NEXT TARGET CUSTOMER

The initial target customer for a TMI is a market segment in transition. Winning the segment leadership position in that market is the point of the exercise and is its own reward. But that is not the only reward.

Once you win any segment, you have elevated yourself into a privileged class, that of companies that have garnered a strong loyal base that will stick with them through thick and thin. This base will continue to support you with references and follow-on business for a long time to come. It makes a great beachhead for entering adjacent market segments. But how do you decide where to go from your first win?

A couple of rules of thumb to keep in mind are:

- It is easier to take a new solution to the same customer than it is to take the same solution to a new customer. Customer intimacy, in other words, is a stronger card to play in the market-power game than product leadership.

- It is easier to enter a new industry than a new geography. This is largely because in the same geography you can usually leverage the same set of whole-offer partners. When you enter a new geography, you are a stranger, and if you have to recruit local companies to the team, you are behind from the outset.

Both principles point to the same underlying point: business is a relationship sport. Yes, we will do volume-operations transactions with perfect strangers, although even then we want the reassurance of a branded product or service. But when it comes to complex systems, we are much happier dealing with people we already know. If one of these folks introduces us to a new party, well and good—that is part of the relationship dynamic, the word-of-mouth that underpins buying decisions great and small.

So the ultimate criterion for a good next target customer is one that already has a relationship with one of your current target customers. That is the way to get the best return on both your marketing and your whole-offer investments.

WRAPPING UP

That wraps up the Nine-Point Checklist playbook for creating market power, specifically when targeting a market segment in transition. It is a remarkably reliable approach to generating escape velocity, particularly for complex-systems vendors. To conclude this chapter, we want to share a case example about a company that took these lessons deeply to heart, capitalizing on a market in transition and profiting dramatically by so doing.

Case Example: A Target Market Initiative at Sybase—2007 to 2010

In the summer of 2007, John Chen, CEO of Sybase, had more or less completed his mission as a “value investor’s” CEO. He had brought Sybase back from near extinction to become a $1 billion software company with highly predictable earnings and cash flow, valued at a little more than two times revenues. In short, he had done a superb job of managing the E in Sybase’s P/E ratio, but he had not really changed the price premium applied to those earnings. Now, he decided, he either needed a new challenge or he had to leave.

The challenge he embraced was to transform Sybase from a value to a growth investment. At the time, the company had some “hidden” crown jewels, both in mobile computing and data analytics, but it lacked the company power to get the larger ecosystem to take it seriously. And when Chen was advised that a market-power initiative could be a path back into company power, he confessed that Sybase, by its own self-diagnosis, was well behind in this area, having the ability to create leads but not to create market power as we were defining it.

In the latter half of 2007, the company took two key preparatory steps toward changing its situation. Under the leadership of Raj Nathan, chief marketing officer (recruited out of engineering!), it revamped its marketing organization top to bottom, realigning it around six key roles: product manager, product marketing manager, field marketing manager, corporate marketing manager, industry solutions manager, and technology marketing manager. At the same time, it activated these six roles by focusing on two TMIs, one in mobile banking, the other in data analytics for data aggregators.

By the beginning of 2008, however, the crisis in the financial sector was becoming a bigger and bigger national issue, and the data analytics team refocused its efforts on Wall Street and the challenge of risk analytics in an increasingly automated, algorithmic, and opaque trading environment. The team rallied around a domain expert, Sinan Baskan, who played the role of industry solution manager, and its New York–based regional sales leader, Eric Johnson, who played the role of the entrepreneurial GM.

Over the course of 2008, the following transpired:

- A Financial Services Council was formed, including direct reports to Chen from marketing, sales, engineering, and mobile transaction services. Chaired by the head of sales, Steve Capelli, to whom Eric Johnson reported, this council ran interference for the TMI when its needs ran counter to the normal inertia of the enterprise. In particular, it reprioritized the engineering road map to release a critical programming capability well before its scheduled time, and it reorganized the field to concentrate worldwide decision authority and field-marketing support under Johnson for the target segment.

- Corporate marketing, headed by Mark Wilson, reprioritized the entire 2008 budget to privilege efforts that supported the risk analytics TMI. This included funding a May event at the New York Stock Exchange where Alan Greenspan was interviewed onstage for an hour, discussing the risk crisis. This event by itself helped Sybase change its profile on Wall Street. The sales force was able to reignite interest in the firm and connect with the line-of-business executives in investment banks who had the power to reallocate budget to solve the burgeoning problem. To be specific, it brought the field team into contact with over one hundred chief risk officers at a time when the overwhelming bulk of Sybase’s customer relationships were in the IT departments.

- The sales team meanwhile, working with the product managers and product-marketing teams at headquarters, developed a provocation-based sales strategy to complement the referrals-based marketing being done by corporate. Each salesperson role-played a dialogue with the target line-of-business executives (who were played by Sybase senior executives), all in a fishbowl environment where everyone could learn from everyone else’s mistakes and successes.

- The Financial Services Council, working closely with the sales team, tracked account penetration progress at each of forty top accounts, meeting monthly to do whatever was necessary to get stalled progress unstuck.

- Finally, as noted above, the engineering team redesigned a critical piece of programming technology in order to accelerate delivery of critical whole-offer functionality, getting it to market well ahead of the prior cadence, where it was buried deep within the proverbial “next release.”

The net of all these efforts was that, despite a complete meltdown in the financial sector (or perversely, perhaps because of it), the financial systems segment outgrew the rest of Sybase eleven to one! This boosted Sybase’s company power and bought time for it to continue investing in its mobile computing initiatives, which were three to four quarters further back in the queue. Those investments came to fruition in 2009 in a number of enterprise mobility offerings, including a critical mobile application for SAP that let them deliver their business intelligence output to BlackBerries and iPhones. And that, in turn, led to an overall interest from SAP in Sybase that culminated in their merger in 2010.

So how did Chen fare with his “growth investor” company objective? During two of the toughest years in recent economic history, he took Sybase’s market cap from $2.2 billion in the summer of 2007 to $3.6 billion prior to the SAP acquisition. That acquisition came in at a whopping $5.8 billion. Not bad for three years’ work, especially when you consider that the valuations in the tech sector had been deeply deflated by the 2008 downturn. And if you look back to the pivot he engineered, the fulcrum for that pivot, the thing that rejuvenated Sybase’s company power and positioned it for its key moves in enterprise mobility, was the market-power initiative of 2008.