Chapter Five

Offer Power: Breaking the Ties That Bind

Thus far in our discussion of escape velocity, we have imagined the pull of the past as a gravitational field holding our rocket ships prisoner to a home planet. That is how categories and competitive sets and even market ecosystems exert their claims on companies and keep them in their place. When it comes to offer power, however, it’s a different story.

To achieve escape velocity, your next-generation offers, the kind that really can free your company’s future from the pull of the past—the way that valued-added services have at Akamai, the way that the BSM suite did at BMC, the way that analytic servers did at Sybase—these offers must free themselves from the entanglements of a myriad of legacy commitments, a long tail of products and promises and one-off customizations, each with its own trickle of revenue, however paltry, each nattering for some share of the sales force’s attention, however small, each tugging at the sleeve of enterprise marketing to get some murmur of the total corporate voice, however faint. This is not gravity at work. This reminds us more of Gulliver.

You remember Gulliver, in the first of his travels, waking up in the land of the Lilliputians, surrounded by little people, unable to move, his giant limbs held captive by an infinitude of tiny threadlike ropes, staked to the ground all about his body. Thus did the six-inch-tall citizens of that land render him powerless to move; thus does the long tail of your legacy offer set exert its power over your next-generation giants.

How is this possible? How can it be that the mighty is so subordinated to the minuscule? In the world of business, it is easy. In any given quarter, you are doing your best to meet your revenue commitments, and not uncommonly you find yourself a bit underpowered to do so and very much at risk of falling short of plan. Indeed, you are much in need of a next-generation giant that could replenish your power. But instead, under the pressure of events and the compulsion to make the quarter, you find yourself taking revenue from wherever you can get it, grasping at any and all straws, fearful of cutting off any source of funds, however small.

We call this behavior picking up dimes in front of a steamroller, and while you know as well as we do this is an unworthy occupation, frankly you do not see any alternative. And so you fall into a pattern we call majoring in minors, in which the better part of the power your enterprise can deploy is diffused across a plethora of inconsequential transactions, all of which may, or even worse, may not equate to making the quarter. When this tactic does succeed, you get to start the next quarter even further behind the eight ball and see if you can pull it off again. And when eventually you do miss the quarter, as inevitably you must because you have not invested in anything that would allow you to really take charge of your destiny, you get to add the ultimate insult to injury, watching a competitor come out with a next-generation product that’s a far cry from what you could have done if only you had just gone and done it. That’s how Sony felt when it saw the iPod and how Motorola felt when it saw the iPhone.

Life is just too short to spend this way. To diffuse power across a landscape of inconsequential transactions is to waste decades of reputation and brand building in an unworthy pursuit, and worse, to ensure that you will never achieve the escape velocity that would free you from this fate. For rest assured, it is the escape-velocity offer that you seek. Offers are the only thing in the Hierarchy of Powers that customers can actually buy. If the proof is in the pudding, they are the pudding. And next-generation offers is our name for that very special subset of offerings that really do change the balance of power in your marketplace.

So how are you going to break out of this tangle? Well, like Gulliver, you are going to have to innovate, not just to create your future but also to coexist in your present and to release yourself from your past. All this entails a much broader model of innovation than most people have in mind, and so it is there that we will begin.

RETURN ON INNOVATION: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE

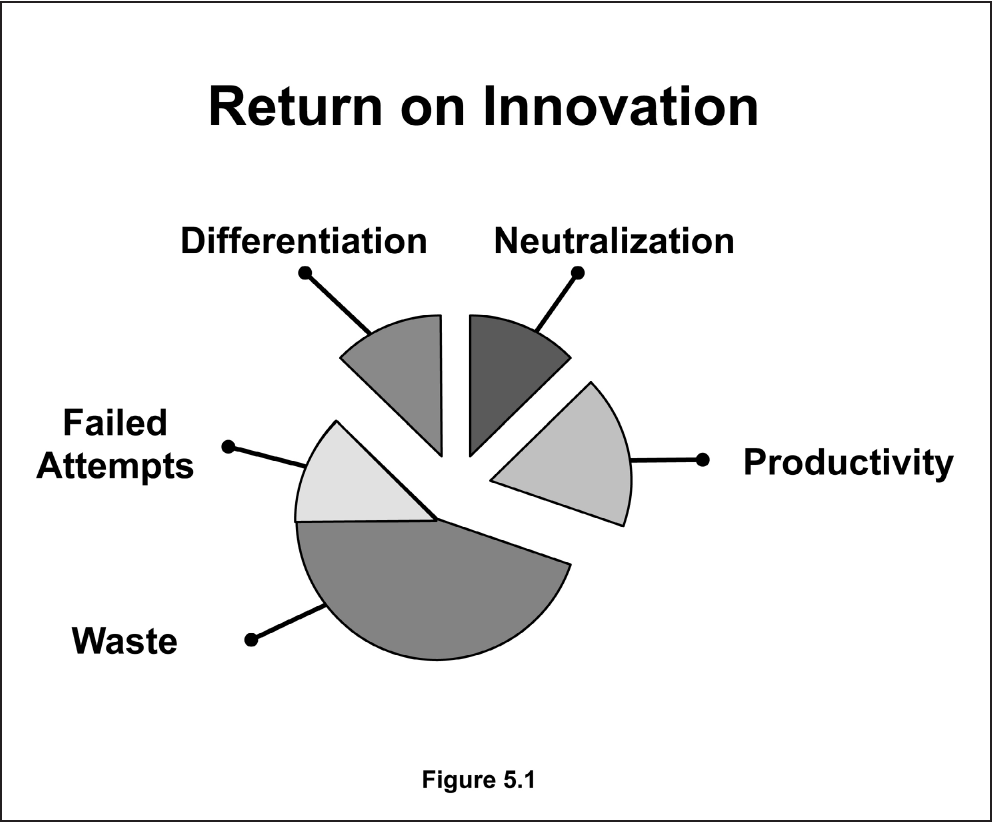

In our study of innovation in Dealing with Darwin, chapter 1, we developed a model to describe three different ways in which innovation creates economic value, along with two others that actually reduce value (see Figure 5.1).

Differentiation innovation is what creates distance from competitive offers, the deepest expression of your core capabilities, the stuff that crown jewels help create, some part of which will be at the heart of your next-generation offer. This is the engine that drives your future.

Neutralization innovation is what catches you up to the changes competitors are making, what keeps you in good standing with your category norms, ensuring you are up-to-date with the latest improvements and compliant with the current standards. Its goal is not to make you different, but to make you the same and to do so as quickly and economically as possible. It represents the bulk of all work in the category and is the engine that drives your present.

Productivity innovation is what extricates you from your Lilliputian commitments, enabling you to resource your next-generation offers to the full extent they deserve. This is the engine that frees you from the pull of the past.

Failed attempts are just that: no program of innovation has a 100 percent success rate, or at least it shouldn’t if you are really trying to push the envelope. When failures happen, you must extract all the learning you can from them and then move on.

Waste is the real killer, the bad cholesterol in your bloodstream that becomes the plaque in your arteries. It takes on different forms, depending on the return on innovation you are pursuing, something we shall dig into in detail shortly. The key thing to remember for now is that waste is recyclable as fuel, hidden dollars already present in your budget you can liberate on behalf of your end goals if you will only, well, stop wasting them.

Following the lead of this model, we will describe a three-part program to drive offer power in your company to escape velocity, as follows:

1. Leverage innovation in productivity to free your resource commitments from the pull of the past,

2. Leverage innovation in neutralization to meet the revenue and profit obligations of the present, and

3. Leverage innovation in differentiation to create sufficient net new power to drive even greater future success.

Pish posh! We should probably have time for tea as well.

PRODUCTIVITY INNOVATION: MELT YOUR DIMES INTO INGOTS

There was a time when the dimes you are picking up in front of steamrollers were in fact dollars, and perhaps a time before that when they were gold pieces and well worth the effort. Now, however, each transaction entails an individually tiny but collectively lethal opportunity cost, each distracting just enough to keep you from refocusing on dismantling the expensive infrastructure required to do this kind of business. You know you can do better, but you never seem to find the time to do so.

Well, now’s the time, and following up on the strategies we outlined in the chapter on company power, here is specifically what you have to do:

1. Put a spotlight on the long tail of products or service offerings that collectively contribute, say, the last 10 percent of your revenue stream. Banish these products from your primary distribution channel. If that channel is direct sales, simply make them noncommissionable, not applicable to quota, not contributive to making the 100 percent club. They can still be included on an order, but for no go-to-market team credit. If your primary channel is retail, take them off the prime shelf space and put them into two-tier distribution, with fulfillment orders taken over the Web. And cease to market them whatsoever. You have not yet completely shut the valve on these things, but you have certainly blocked them from taking up valuable time and space in the go-to-market channels that matter to your overall success.

2. Put the entirety of the long tail under the governance of a single optimizing manager who is incented to extract resources and residual cash flow from these offers while minimizing customer dissatisfaction. Take revenue credit for these products away from the hosting organizations, but do not transfer the resources working on these offers. That gives them the L in a P&L without the P. At the same time, give the long-tail manager the right to take over any of these resources he or she feels will help maximize cash flow—at that point, they do transfer—but this should be entirely at the long-tail manager’s discretion, because there is no way to make residual cash generation work properly if you are a safe harbor for wounded products and stranded human assets.

3. Put in place a cross-functional end-of-life (EOL) process under the governance of this same optimizing manager that proactively attacks this problem before it becomes truly pernicious. The process should give plenty of warning and visibility into the status of end-of-life offers. Salespeople, channel partners, and current customers all should get one last bite at the apple. After that, they should be redirected to the new product road map for their future needs, or to a partner if those needs cannot be met in-house.

Under this plan, business units and other P&L entities are strongly incented to integrate EOL into their core planning and operations. When they fail to do so, they get taxed by virtue of having to resource an offer for which they get no revenue credit. The company can still make money from this offer, but the BU cannot. If that does not get their attention, then perhaps a change in management is in order.

The stock-keeping unit (SKU) is the easiest measurable unit of this kind of product rationalization, but in software and services, there are special configurations, unusual terms and conditions, orphaned code branches, and the like that cause the same problems. None of these can be addressed effectively within the units that host them. Not only is the web of favors just too strong; the skill set for optimization is too weak. It is critical, therefore, to organize productivity optimization outboard of the organizations you are seeking to optimize.

Finally, be ambitious for this effort. We really do believe you can melt dimes into ingots, and that those ingots can prove to be sustainable corporate assets. There is real cash to extract here, the supply of dimes is endless, and there is always a market somewhere for them, albeit not one you will access through your mainstream go-to-market channels. Just remember, no matter what you deem to be context, no matter how lacking in value it seems to you, it can be someone else’s core.

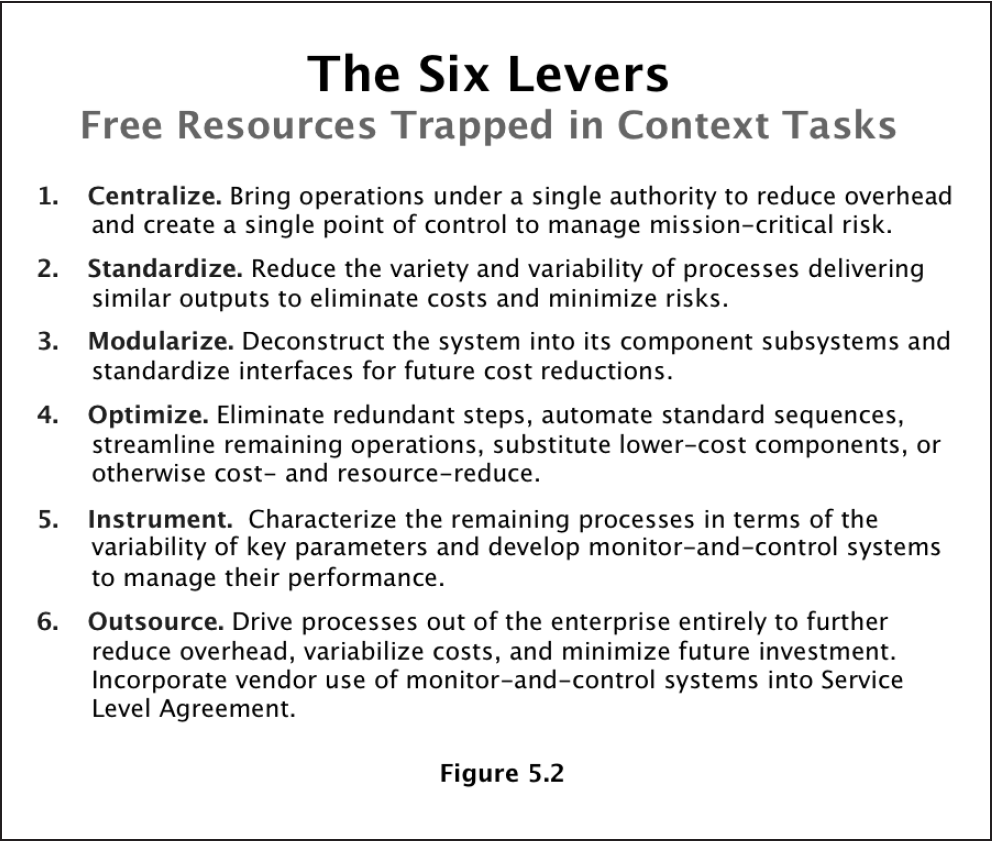

The framework that underlies the playbook for productivity innovation is the Six Levers model, modified from an earlier version presented in Dealing with Darwin, chapter 9. Let me recap it here so you can see how the smelter effect we are calling for is actually brought about (see Figure 5.2).

Levers 1 and 2 allow an organization to take control of a diffuse and dispersed set of products or practices by putting them under the direct supervision of a single executive, one who has a strong bent toward optimization. That executive will immediately begin to standardize disparate context activities as a means for reducing cost and diminishing risk. This will result in a significant release of resources on a one-time basis.

Levers 3 and 4 represent a second phase of productivity improvement. Here the optimization team deconstructs the most resource-consuming processes to more precisely target the major points of greatest inefficiency or ineffectiveness. These are hived off from the rest of the standard workflow to be reengineered for substantial performance improvement. This process of isolating, hiving, and improving modules of work continues until the bulk of the available gains have been achieved.

Levers 5 and 6 represent the final phase of optimization. At this stage the optimized processes are packaged for more efficient ongoing management and administration. This may occur in some form of automated system or an outsourcing agreement. In either case, management needs instrumentation to monitor the ongoing performance of the system, and that must come before its final disposition is approved.

As you can see, the six levers represent a systematic approach to squeezing out the costs from any set of products or processes. When you centralize the long tail, expect a last-minute flurry of innovation as offers try to combine with one another to get enough bulk to survive. That is the ingot-making part of the effort. If they do not, then it is time to sluice away the detritus. In technology-based businesses, there is always something worthwhile to recycle; it just has to find a home that is more sustainable to maintain than its current orphan status.

So let’s say this job is done. It won’t be that easy, but you should make consistent headway if you follow this approach, and you need to attend to two other types of innovation in parallel, each of which is even more critical to your future. You have got Gulliver untied, but he is still not a free man.

NEUTRALIZATION INNOVATION: MAJOR IN MAJORS, AND QUICKLY!

How can we call something innovation when its goal is to make you the same as someone else? True innovators should be too proud to copy, shouldn’t they?

Well, should Nokia have copied Apple’s haptic interface, or should it have not? At the time of this writing, it has allowed Apple to retain that differentiation for three and a half years, despite the overwhelming consumer sentiment in its favor. During this time RIM copied it for their BlackBerry, and Google for its Android, and Motorola embraced the Android and Google for its Droid smart phone. As a result, all three are in the smart phone hunt in 2011, and Nokia is nowhere to be found. This has had a devastating effect on its brand, calling into question its long-term viability. Sometimes pride is misplaced.

Neutralization innovation is the energy that drives the bulk of any current book of business. It is what keeps you in good standing with your customers, your partners, your suppliers, even your competitors. It lacks the glamour of differentiation innovation, but in terms of pure ROI, risk-adjusted, it is by far the best investment you can ever make. And that is why the bulk of your people spend the bulk of their time making sure you are just keeping up with the myriad of innovations coming out of your industry.

Why is this so valuable? Think about it from your customers’ point of view. Most of the time they just want to buy more of the same from the same vendors through the same channels, just so long as the offers are keeping pace with the competition. That’s because the transaction costs of reevaluating a whole new raft of products, qualifying a whole new set of vendors, and adapting their current systems to a whole new set of technical and organizational interfaces is normally not worth the effort.

So while keeping pace is not a very high bar to clear, its rewards are considerable—low cost, relatively predictable sales involving knowledgeable and thus easy-to-support end users—what’s not to like? How could anybody screw this up?

The answer is as simple as it is painful—people don’t want to follow; they want to lead.They don’t want to copy; they want to create. But now is neither the time nor place for either.

When all the market is asking for is “good enough,” yet we insist nonetheless on giving more than that, and worse insist on calling this delta value, we are doing everyone a disservice, not least of all ourselves. Even if we present this new offer at the same old price, we have typically overengineered it for most purposes and would have done better either by reducing price to capture new, less affluent customers or by raising our gross margins to fund other initiatives within our enterprise. And worst of all, we have taken time—often lots of time—during which our offers were not competitive because we had not gotten something “good enough” out in the interim.

As we have just noted, this is the fix that Nokia got itself in relative to Apple. By contrast, look what Microsoft did to neutralize Apple’s Macintosh innovations in the prior decade with its Windows operating system, or what Google is doing to Apple’s iPhone innovations at present with its Android platform.

So what is the right way to play the neutralization innovation game? In a word, speedily. Basically, there are two primary reasons to invest in neutralization. The first is to catch up to a competitor who has achieved escape velocity with its latest offer. The goal here is not to beat them at their own game, or even to equal their success, but rather to be good enough that your customers see you as competitive. You don’t dominate by these efforts—you just get yourself back in the game. So the key metric is, how fast were you able to do so?

The other reason to invest in neutralization is to contribute to your industry’s overall progress, producing a handful of new features from the top of your customer base’s wish list, thereby showing that you are continuing to invest in their interests. Some of these may simply involve cleaning up hygiene-factor issues, others may be genuine delighters, and all are welcomed. But there is no intent here to generate escape velocity. You don’t want to escape from these customers; you want to nurture the relationship with them. So nothing terribly disruptive, just good sustaining innovation to make things a bit better, and as before, the sooner the better. Don’t leave openings for your competitors to get in and disrupt these relationships.

Both of these types of innovation need to be watched over carefully, because their fundamental goals run counter to the interests and instincts of R&D teams. No engineer gets up in the morning to be “good enough.” “Best in class” is more like it. But here’s the thing: Best in class is a sucker’s bet!

Customers don’t pay a big premium for best-in-class offers; they pay a small increment over the mean. They do pay a big premium for beyond class, the unmatchable offers we will discuss in differentiation innovation. And they do impose a penalty for being not in class, meaning you have slipped below the expected norms of any company in the category, presumably by not neutralizing fast enough. But for everything in between good enough and best in class, the premium paid comes nowhere near covering the cost.

Best in class ends up being nothing more than the most expensive version of being in class. You spend all of your R&D budget, and you have precious little to show for it. Exhibit A for this is General Motors over the past twenty years. Exhibit B is Microsoft Office over the past ten years. Exhibit C is SAP ERP over the past ten years. Contrast these massively expensive, hugely time-consuming low-yield efforts in neutralization innovation—remember now, we are not dealing with escape velocity here, just business as usual—with the lights-out successes of Dell in the 1990s or HP in their PC business in the past decade or Intuit over both decades. None of these companies produced an escape-velocity offer during the period, but all have leveraged frugal, well-managed, and most of all, timely neutralization innovation to great avail.

Of course the greatest neutralization innovation performance of all time goes to Bill Gates during his leadership of Microsoft. In the course of a couple of decades he neutralized escape-velocity offers from Lotus 1-2-3, MicroPro WordStar, Ashton-Tate dBASE, Aldus Persuasion, Novell Netware, Lotus Notes, and Netscape Navigator—hijacking billions and billions of dollars of revenues right from under their very noses. At no time did he have to make the best spreadsheet or word processor or file server or e-mail client to win. He had to make ones that were good enough to be competitive, and that he did with both speed and verve.

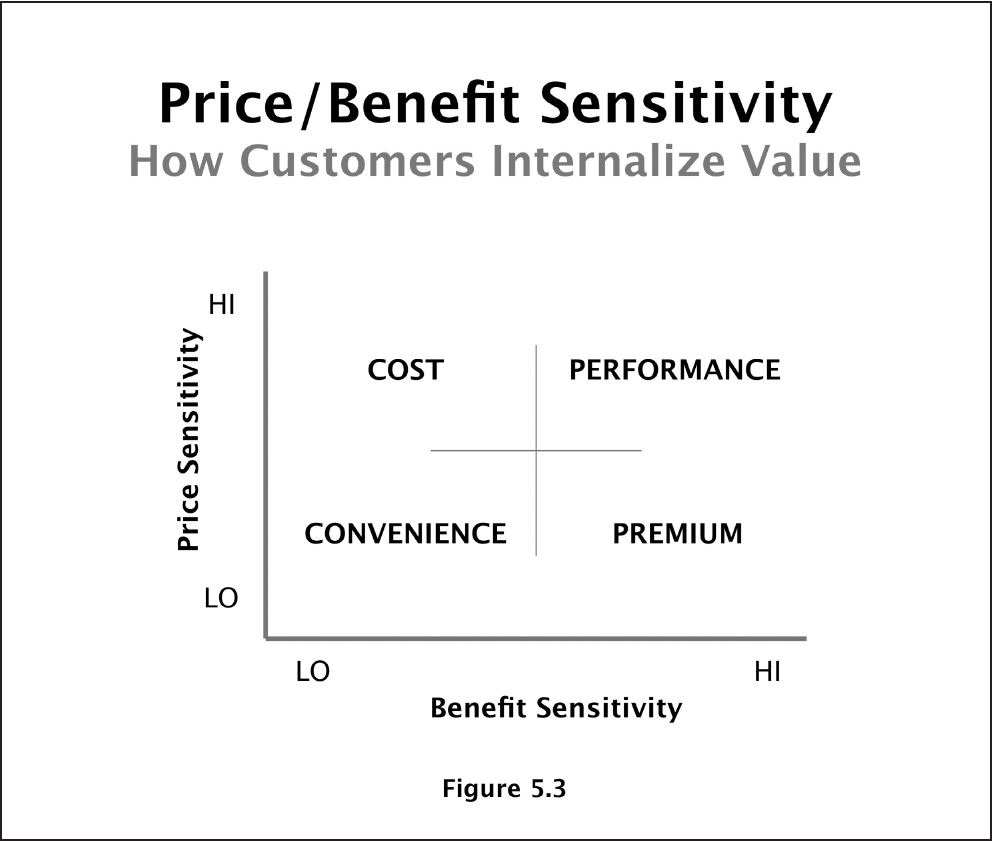

How do you do this? How do you keep R&D focused on pursuing true value creation and keep it from chasing mechanical rabbits around a racetrack? The key is to fence in the effort so that it produces the effects you care the most about, the ones that will truly resonate with your target customer. Here is a simple framework that can help with that targeting (see Figure 5.3).

The premise of this framework is that, for almost any class of purchase, customers self-segregate into one or another of these four quadrants and then choose their offers accordingly. Take yourself for an example:

- If you are very engaged in the benefits of an offer and not sensitive to its price, then you are in the premium quadrant, and luxury goods and services vendors worldwide seek your acquaintance. This is how I feel about Mont Blanc ballpoint pens, particularly the Authors series.

- If, on the other hand, you long for such benefits but are price sensitive, then you are in the performance quadrant, and you can spend hours determining which is the best buy—good, better, or best? This is how I feel about wine, especially Meritages; I am a bit of a sucker for a good shelf talker.

- Now, if you are not particularly benefit sensitive but you are price sensitive, then you fall into the cost quadrant, and lowest price is your primary decision criterion. This is how I feel about water served in restaurants—the tap water is just fine.

- And finally, if you are neither benefit sensitive nor price sensitive, then you are in the convenience quadrant, and you would just like someone else to make this decision for you. For me this is the zone for home-maintenance services.

Stepping back from this model, you can see, I hope, that spreading a neutralization budget evenly across all four quadrants is a bad idea. Indeed, it is hard to come up with a formula that could create more waste than that one—and yet, it is the most common one we see. Why? Because when you peanut-butter innovation across all bets, then everyone gets a taste, and nobody can call you out. Unfortunately, however, you end up underperforming in the quadrants that really matter, creating openings for your competitive set.

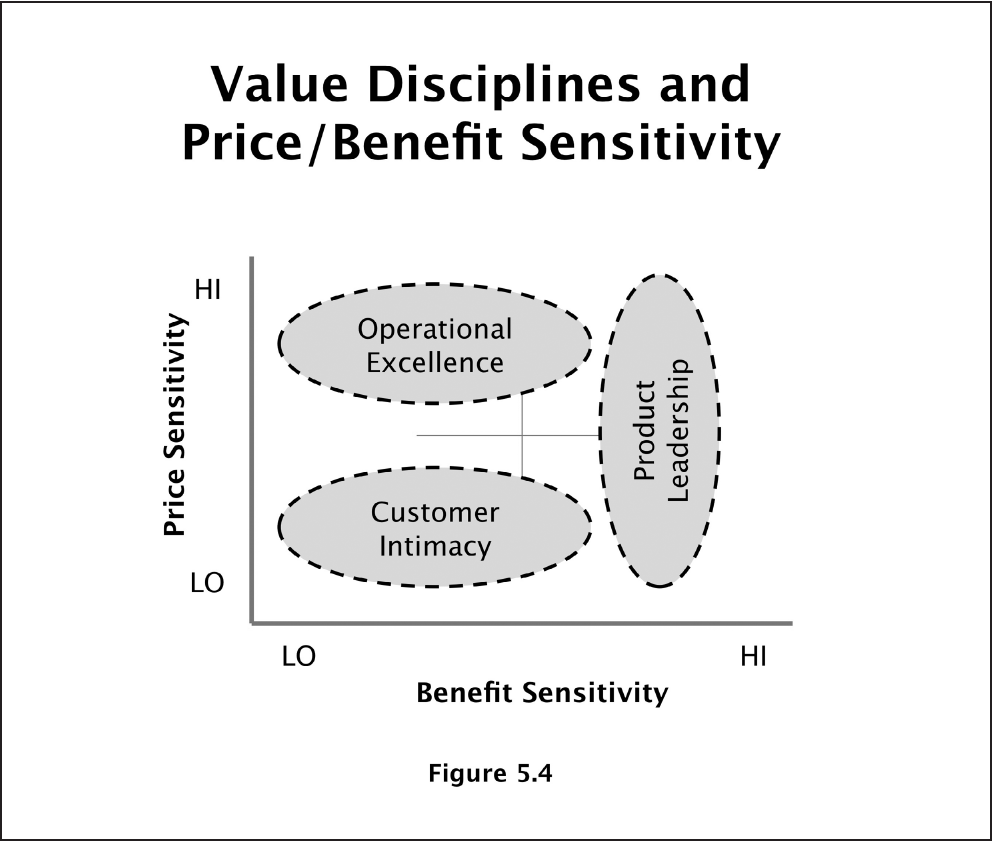

The right way to play this model is to bet on that pair of quadrants that best aligns with your core value proposition. To keep it simple, we will use value disciplines as a proxy for whatever that may be. In that context, here are the squares on which to place your bets (see Figure 5.4).

- Product leadership strategies are inherently targeted at benefit-sensitive customers. It’s up to you whether you want to start with premium and grow into value, or start with value and grow into premium. Just keep to the right-hand quadrants. You must neutralize every benefit that is competing for your target customers’ attention.

- Operational excellence strategies are inherently targeted at price-sensitive customers. Whether you start with a commoditization play on the left and grow into quality, or start with quality and pare down for lowest cost, just make sure you focus your innovation budget on the upper two quadrants. You cannot allow a lower-priced offer to go unchallenged.

- Customer intimacy strategies, by contrast, are all about earning a price premium and thus attracting customers who are not price sensitive. Whether you are playing a premium game or a convenience game is up to you, but this is one case where the one does not normally grow into the other. You should probably stick to just one of the bottom two quadrants to get the best bang for your innovation buck. You cannot allow some other vendor to worm their way past you in your target customers’ affections.

However you end up sorting out your priorities, just remember two rules: Don’t chase and Don’t apologize. That is, maintain the discipline of focusing your neutralization efforts away from the two quadrants that don’t matter. Let your target customers’ preferences be your command. Your colleagues’ second guessing should come in a very distant second.

Remember, we have been talking all this time about neutralization, not differentiation. The rules we have laid out help you keep the customers you have by ensuring that the money you spend on them goes where they will most reward it. This does not, however, help you gain new customers. Or to return to the analogy with Gulliver, we have him upright and operating as a free man in Lilliput, but we still have no way to get him back home. For that we will need a stronger value proposition, one that can woo away our target customers free from their current vendor loyalties and win them over as first-time buyers. In short, what we now need is differentiation innovation.

DIFFERENTIATION INNOVATION: “TAKE IT TO THE LIMIT, ONE MORE TIME”

When we talk about differentiation, we have to be careful. Everything is different from everything else, so by definition some amount of differentiation will result from any innovation you undertake. That is not what we are talking about here. Here, to get escape velocity, to get Gulliver out of Lilliput and on to Brobdingnag, we are talking about what Andy Grove calls the 10X effect.

The idea is simple. For a new offer to change the balance of power in any category, it needs to deliver value along some dimension that is an order of magnitude greater than the current market standard. An order of magnitude. How are you, how is anyone with a normal budget for a next-generation product, going to accomplish that?

The answer is, by making a very asymmetrical bet. In the language of core and context, you are going to treat every dimension of your new offer but one as context, and you are going to ruthlessly prune your investment across this universe of possible spend in order to put all your chips on one, and only one, square on the roulette table. You may not succeed, but you sure as heck are going to get noticed.

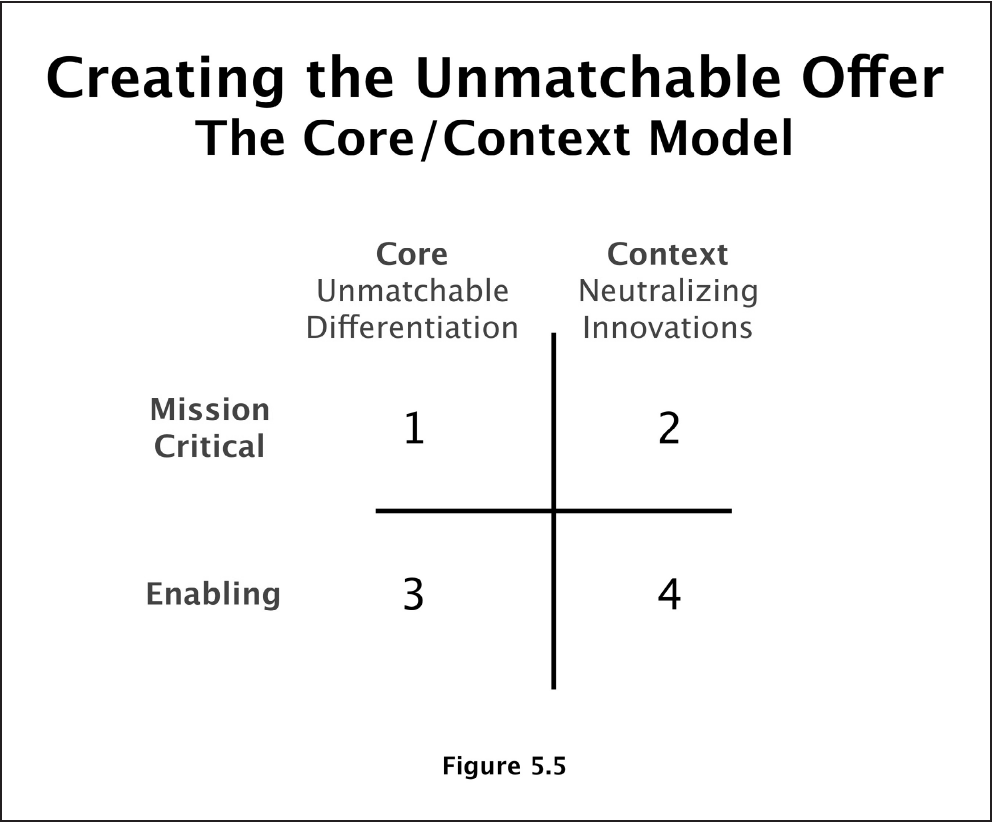

Here is the model we use to help teams come to grips with this challenge (see Figure 5.5).

Core is whatever contributes directly to the unmatchable differentiation of the offer in question. Context refers to all other features and properties. Clearly, the overwhelming bulk of the content of any offer is context, not core. But this is not a situation where size matters. It only takes a tiny bit of saffron to turn rice into paella, but it is all about the saffron. Same story with core. You will do whatever it takes to get the very best ingredients for core, making sacrifices wherever else you must to do so.

Nevertheless, the trade-offs between core and context are not made in a vacuum. There is another dimension to the unmatchable offer that must be taken into account—its overall performance relative to the category’s current norms, norms set in part by competitors who are off touting their cores. In relation to meeting norms, the key distinction is between those that are mission-critical and those that are simply enabling.

A mission-critical norm is one you cannot fail to meet. Doing so will cause your offer to lose credibility in the category, leave it open to competitive attack, and detract from its more innovative features. This is what happened to the Apple Newton, for example, which was quite innovative for its time but which had a handwriting recognition capability that simply did not work. At the same time, it is crucial that work against mission-critical norms be resourced as neutralization innovation, along the lines we just laid out, as it is easy to be seduced by the siren call of best in class, especially when your context is someone else’s core.

In activating the model, there is a priority of the quadrants relative to one another. In essence, you prioritize quadrant 1 (mission-critical core) over all other quadrant’s goals, and after that, you will prioritize quadrant 2 (mission-critical context) over any enabling elements. If you have resources left after that, you will tilt them strongly toward quadrant 3 (enabling core). Quadrant 4 (enabling context), if at all possible, you will outsource.

Now given the enormous priority granted to mission-critical core, it is vital to choose this highly privileged dimension with care. First of all, make sure there are customers out there who would leap at the chance to get something 10X along the lines you have in mind. And second, make sure that the 10X improvement you seek is made possible, ideally uniquely possible, by your company’s core capabilities and its crown jewels. This is key because it is unlikely you can ever create an order of magnitude differential acting on your own, and even if you could, it is unlikely you could keep others from copying you once you released your offer.

In sum, we need a highly desirable 10X effect enabled by our core capabilities and crown jewels. Consider, where you have seen examples of that? And just to keep you on your toes, I’m going to ban using Apple as an example, spectacular though it may be in this regard. Try the following instead:

- Salesforce.com created a 10X reduction in enterprise software installation and operating costs compared to the industry standards of Seibel, Oracle, PeopleSoft, and SAP. It did so by leveraging its core capabilities in hosted software architecture and the software-as-a-service business model.

- Skype created a 10X reduction in consumer long-distance telephony costs by offering it for free, anywhere in the world, as long as you were calling another Skype user. It did so by leveraging its crown jewel, a peer-to-peer Internet protocol that makes every subscriber’s computer part of the underlying network.

- Cisco created a 10X improvement in the videoconferencing experience, creating what they call TelePresence, by leveraging their core capabilities in routing and switching over the Internet protocol.

- Wikipedia created a 10X improvement in the accessibility and currency of an encyclopedia, outpacing the global standard of the Encyclopædia Britannica in less than a decade and forcing Microsoft’s Encarta out of business. It did so by leveraging its crown jewel, a collaborative governance model leveraging a cadre of generalist volunteer editors who in turn leverage a myriad specialist volunteer contributors.

- VMWare created a 10X reduction in the cost of data center provisioning by harnessing all the redundant capacity lying dormant in each and every computer and storage device. It did so by leveraging its hypervisor virtualization technology across a heterogeneous landscape of resources.

These are not exceptions. In the prior decade, Palm Computing created a personal digital assistant that was 10X more usable than the electronic organizers and pocket computers available at the time, leveraging its pen-based computing language called Graffiti; Dell gave us a 10X better shopping, buying, and support experience compared to IBM, Compaq, and HP, leveraging its Dell direct sales channel and build-to-order supply chain; and Motorola gave us a 10X more elegant mobile phone, the RAZR, leveraging its crown jewels in radio technology to enable a thinness previously unimaginable.

No, it is not particularly astounding that products deliver 10X effects. It is rather somewhat more astounding that we do not make them do so more often. How come? OK, to be fair, it is not that easy. But it is possible more often than one would think. So what holds us back? In a nutshell: the asymmetry of risk.

Established enterprises, unlike start-ups, have a lot to lose: brand reputation, customer loyalty, market capitalization, just to name the top three. Moreover, when they make missteps, they are natural targets for lawsuits, further adding to the risk side of the equation. And finally, from a personal career trajectory point of view, most organizations tend to reward managers with unblemished records, withholding the top jobs from leaders who have taken big falls in the past.

The consequence of all of the above is as predictable as it is disappointing. Would-be leaders hold themselves back, checked by the fear of making a truly asymmetrical bet, the risk of looking like a fool. Not always, of course. We do have role models, people like Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, Larry Page, Sergey Brin, Shai Agassi, Jeff Hawkins, John Chambers, and Jimmy Wales—and if there is anyone on this list whose name you don’t recognize, by all means Google them; they will be there with page after page after page of hits, because that is what their kind of leadership and success in creating 10X effects leads to. Here’s my point: You too can do this. You. You who may not even have one page of Google hits. You who may have a next-generation product budget that would not buy the fuel for an hour’s flight in Sergey and Larry’s private jet. You can do this. Not every time. Not without help. Not without some really good crown jewels. But look around—are you really ready to say that those things are not available to you right now? In most of the firms we work with, the ingredients for creating 10X effects are present most of the time. They have been present in IBM for the past two decades, as they have in GE, GM, Intel, Oracle, and HP.

If you work at great companies like these, companies that have shipped 10X offers in the past but not recently, you do not lack the wherewithal to do it again. What is holding everyone back is the asymmetry of risk, so that is what you must put on the table. Until the risk of not producing a 10X offer begins to approach the risk of attempting to produce such an offer, it will be hard for the organization to commit. Nokia understands this risk today in a way it did not several years ago. So does Motorola. So does Dell. So do Kodak and Xerox. It is no coincidence that all these companies are taking much more aggressive actions today than they were in their recent past. They are making 10X bets now, not just because they want to, but frankly because they have to.

So why wait? Do you really think your company is immune from the disruptive forces that have shaken these other companies to their foundations? Do you really think it is safe to hold back in these times? Use the Hierarchy of Powers to take a good look at your current risk profile and you may discover that the asymmetry you presume exists is not there at all, not because the traditional risks have diminished but because the novel ones have expanded. If that is the case, then making the 10X bet may be the safest thing you can do. And the sooner, the better.

WRAPPING UP ON OFFER POWER

Offer power takes up more of the total management conversation than any other element in the Hierarchy of Powers. This is certainly understandable, as it is the only tier in the model where revenue can be earned. But most of what goes into offer power is best managed close to the product, the channel, and the customer—not in executive boardrooms.

Where executives can make a difference in offer power on a daily basis is in organizing the company explicitly around the three goals of innovation that structure this chapter: productivity, neutralization, and differentiation. The key principle is that every initiative should have one of these three, and only one, as its defining objective. Where teams are allowed to pursue two or more, waste inevitably ensues, followed by mediocre performance in the market, loss of momentum and morale, and general decay.

That is the situation that the management team at Symbol Technologies inherited when it took the helm in 2003. It was also the situation at Adobe when Rob Tarkoff took over its enterprise systems business. How each of these organizations responded demonstrates exemplary engagement with offer power.

Case Example: Creating Offer Power at Symbol Technologies—2003 to 2006

When Bill Nuti took over as CEO of Symbol Technologies, the company was reeling internally from the effects of an accounting fraud and externally had been experiencing a steady decline in market share over the prior five years in the very categories they led—namely, bar-code scanning and rugged mobile computing. He and his key lieutenants, Todd Hewlin, head of products; Todd Abbott, head of sales; and John Bruno, head of marketing and M&A—took matters in hand in the following ways.

Following the principle that one should articulate the future before making cuts in the present, Bruno led a repositioning of the company around three key data management capabilities—Capture, Move, and Manage—creating a comprehensive architecture that leveraged crown jewels from the first two (bar-code scanning for Capture and rugged mobile computing for Move), and creating a need for Manage (a software layer, to be developed both organically and through an acquisition, to connect these edge systems to an enterprise’s core IT). In effect, the team was able to put a new category in play—enterprise mobility—and carve out its part of the market—blue-collar and gray-collar workers (the former working more outdoors, the latter more indoors) as opposed to white-collar and no-collar (the former being professionals with smart phones, the latter being low-income consumers with feature phones). This enterprise mobility strategy enabled the company to breathe new life into its strongest markets and provided both engineering and sales with a vision to follow.

On the product side, Todd Hewlin confronted a highly fragmented R&D landscape in which rafts of products were all being created independently of one another. As a result, the company had some seventeen thousand SKUs and $100 million in excess inventory and spares for a revenue stream of $1 billion. He and his team laid out an operating plan to innovate in productivity, neutralization, and differentiation on parallel paths, all governed by a road map leading to the enterprise mobility vision, all organized around investing in a common platform architecture to underpin the full scope of Symbol’s Capture-Move-Manage capabilities.

This road map was key to the productivity initiative. The team was able to map every existing product and SKU to a point in the road map at which it would be displaced by a platform-enabled product—in effect, its end-of-life date. In this way some twelve thousand SKUs were targeted for elimination over a two year period. The EOL program manager, Suzanne Wenz, drove this effort on a “no surprises” basis for the entire two years. Customers and channel partners got ample warnings of EOL with plenty of time to make one last “lifetime buy” before the SKU was eliminated. And marketing and sales were both armed with the road map and the value propositions behind the new products so they could ease customers through this transition.

Meanwhile, development was coming out with next-generation products atop the new technology platform. This enabled more resources to go into new features as opposed to enabling infrastructure, including the ability to:

- Make the same rugged mobile computer look like a gun, a brick, or a big PDA, depending on the customer’s preference;

- Make keyboards (which wear out fast) that were field replaceable;

- Extend battery life to a full shift (a very expensive engineering task, but one that had to be done only once, after which it could be applied across the entire product line);

- Ship a variety of different devices that could all use the same cradles and accessories instead each having its own proprietary requirements; and

- Provide a common software stack so that customers’ applications could run on any of the devices instead of having to be written for each device separately.

Interestingly, impressive as it is, this list of features did not create escape velocity, but as neutralization initiatives they certainly got the customers’ engines revving. As it turned out, the critical differentiation vector, the one that did definitively set the new Symbol product line apart from all its competition, was a 10X improvement in ruggedness—effectively taking a major customer liability off the table. For when a rugged mobile computer breaks, the business process it is enabling comes to a dead halt. This is a huge pain point for a substantial number of field sales and service organizations.

The new product survived not two hundred (the industry standard) but two thousand drop tests from three feet and was the first device ever certified for drops from seven feet. This major change in standard, supported by the new features, allowed one new product line called the MC-9000 to earn a whopping $240 million in its first year—by that time over one-seventh of the company’s total product revenue.

Now all of this would not have happened without innovation on the go-to-market side as well. Here the company translated its system vision into a series of vertical market initiatives led by market managers who were accountable for revenue quotas for each of their respective target markets. This helped prioritize development while ensuring that field sales had valuable propositions and products to pitch.

At the same time, product managers imposed a discipline of good-better-best onto product lines that heretofore had grown like Topsy, with dozens of variants of better, all competing with one another, while there was little coverage for either good or best. But the former are key to recruiting entry-level channel partners, and the latter to winning major accounts, so once the new discipline was installed, Symbol’s success on both fronts jumped dramatically.

On the sales side, Todd Abbott converted a product-oriented sales force, which was selling custom solutions to every single customer, into a platform-oriented solutions sales force, aligned by vertical target market. This transition, not unexpectedly, was painful, as many people and relationships had to be reoriented or replaced. In the midst of this, when customers complained about their old “tried and true” custom solutions going to end-of-life, Abbott had to hold firm and not let even the biggest customer drive any backsliding in the productivity rationalization effort. His message to his troops was simple: Sell what you have today, not only because that is better for Symbol, not only because that is better for the customer’s future, but because it is the best stuff we have. Stop wasting your time with the old stuff, picking up dimes in front of steamrollers. Stop majoring in minors.

The net outcome of all this was to drive up product revenues from $1.1 to $1.5 billion over a three-year period, leading to an acquisition by Motorola for $3.9 billion in 2006, an appreciation in market cap of 300 percent from the time the management team took over—all done within the same set of categories, all within the same set of vertical markets, hence a real testimony to offer power.

Case Example: Creating Offer Power at Adobe—2008 to 2011

In 2008 Rob Tarkoff was head of strategy and M&A for Adobe, famed earlier in its history for PostScript printing and the Acrobat Reader, touted more recently for its Creative Suite for digital designers and its Macromedia Flash Player for video on the Web. The then-new CEO, Shantanu Narayen, asked Rob to take on a different challenge—lead the enterprise software side of a corporation that was predominantly focused on consumer markets. Tarkoff inherited a mature business in Acrobat and a stalled business in software development tools for enterprise workflow. The business was definitely stuck inside the circle of his current competitive set, and no one had high expectations the situation would change, something which inevitably leads to loss of ambition, lack of discipline, and very slow cadences in development.

What did Tarkoff do? First he articulated a whole new vision for the enterprise group. They would help their business customers renovate their consumer-facing systems to bring them up to the new user experience standards being set by Google, Facebook, and the like. They called this effort Customer Engagement Management or CEM. To bring it to fruition, they would leverage Adobe’s Creative Suite, the enterprise IT tools, and the company’s user experience consulting group. He launched this vision, and in the next year the company conducted projects with a handful of flagship customers demonstrating the feasibility of this offering. But people both inside and outside the company were still highly skeptical that Adobe could fulfill this vision for enterprises on a scalable basis with the tools they had.

Tarkoff’s next step was to lay the groundwork for an escape- velocity move. He assigned a key aide, Rob Pinkerton, to head an initiative to pick a chasm-crossing beachhead segment, one that would take the CEM initiative through the Horizon 2 gap. Pinkerton leveraged our firm to help drive this effort. Here was Tarkoff’s take on that:

The biggest hurdle we faced in transforming an atrophying story around Adobe’s Enterprise workflow solution into a birthright to lead customer experience was getting everyone in the boat rowing together. The language, frameworks, and structure of the project gave us the confidence to do this. Every conversation became fortified by the same words, concepts, drill-downs on appropriate (rather than rat-hole) topics that helped advance the strategy and define our opportunity in the market. We saw possibilities we never imagined. More important, we developed an internal cadence that energized the business in completely new ways.

In addition, this project allowed everyone on the team from Tarkoff on down to get laser-focused on what was core to the success of the CEM initiative. Once they did, it became clear that Adobe was underpowered to deliver in some key areas. So that led Tarkoff to champion the acquisition of Day, a critical integrating platform for the CEM offer, referred to as the “hub of online interactions” for customers in their internal strategy documents. It also led him to drive for tighter integration with Omniture, an earlier acquisition that was being managed stand-alone and by so doing gave Adobe more credibility in the offices of marketers and enterprise buyers.

As these pieces came together, Tarkoff made a series of management changes under the new rallying cry of “All in!” This upped the cadence throughout his organization, throwing new leaders (including key members of the Day team) into high-energy, almost frenetic pursuit of the CEM mantle. It fundamentally changed the rules on what was allowed and encouraged within the organization and liberated the formal and informal CEM leaders to pursue new strategies for sales enablement and solution development. At the same time Shantanu Narayen, CEO, saw the potential and gave the CEM initiative a prominent position in Adobe’s quarterly investor-relations communications and in internal discussions about the core growth engines at Adobe. This was a bold move indeed because Adobe was entering a market where they had no significant track record to date and were claiming they were going to revolutionize it overnight.

The market response was extraordinary. Within the first quarter of launching the new Day-powered platform, Adobe was invited into face-to-face conversations with the top executives in over fifteen Fortune 500 companies with consumer-facing businesses. For the first half of the year the pipeline swelled as these conversations became a more prominent part of the marketing and line-of-business agenda. Adobe experienced tremendous wins at major customers, and as the company looks ahead to the rest of 2011, the prospects for growth in this sector are exceptional—significantly higher than any other portion of the business—placing the company on a very fast track to the materiality targets that signify a successful passage through Horizon 2.

Such is the power of offer power.