The “Spirit of Marikana” and the Resurgence of the Working-Class Movement in South Africa1

Trevor Ngwane

What is the political significance of the police killing of thirty-four miners who were on strike in Marikana? I think the strike represents a high point in what are still the early days of the workers’ movement resurgence in South Africa. For a short while the strikers at Lonmin stood heroically at the fore of the workers’ struggle against the bosses, thus becoming a true vanguard of the working-class struggle. They were rebelling not only against their exploitation at the workplace but, it seems to me, also against the oppression and misery of substandard living conditions in the shantytowns of Rustenburg, or what may be called South Africa’s “platinum city,” where the majority of them live. A wave of strikes followed, spreading to the gold and coal industries, and in 2014 a strike shut down all the platinum mines for five months.

The politics behind the Lonmin strike were revolutionary because the demands were based on what workers actually needed rather than what they thought the bosses could provide for them. The strikers continued the fight for several weeks after scores of their comrades were shot dead, injured, or arrested; the general attitude was that it was better to shut down the mines and even to die than to continue being exploited and oppressed by the mining bosses. “Nothing could be worse than being forced to work and live like this,” the workers seemed to be saying. It was more than a strike.

Marikana was about workers risking their jobs and their lives—fighting with collective determination, shared knowledge, and unwavering commitment—for a vision of a life that is different: decent, comfortable, and secure. Revolution happens when millions of workers stand together in united mass action with that vision—a revolutionary vision. This is what I call the “Spirit of Marikana”: the combative and inspired movement of workers against all odds.2

Even before the acrid smell of cordite and tear gas had cleared on that fateful sixteenth of August, 2012, conflicting versions and interpretations of the day’s events were divided along class lines. The ruling class and its apologists watered down news of the massacre and blamed the workers. The miners themselves, as well as other progressive forces, condemned “those who pulled the trigger and those who pulled the political strings,” pointing out that behind the massacre lay “the toxic collusion of capital and the state.”3 The massacre sharply revealed people’s loyalties: for or against the capitalist class. Fence sitting is difficult when matters come to a head in such a dramatic fashion; everyone has to choose a side. Unfortunately, the fact of the massacre itself distracted the public from learning the details of how the movement was organized, how it carried on in the wake of the massacre, and how it eventually ended in victory for the workers. The workers vowed to continue the struggle until the demand for R12,500 was won, saying that this was imperative in order to assuage the spirits of the dead and ensure they had not died in vain. This aspect of the Spirit of Marikana led the miners to go on strike again in 2014, behind the same demand.

The 2012 strike was organized and led by a strike committee that the workers elected from among their own ranks. Historically, workers have created their own forms of organization, outside and often against their unions and parties, during rapid upsurges of rank-and-file resistance or in revolutionary situations (Cohen 2011; Barker 2008). It is this “organic capacity” of the working class that I wish to highlight—that is, the ability of workers to fight for their needs and in the process displace established mediatory mechanisms by their spontaneous, autonomous actions (Ness and Azzellini 2011). The fight was led by and the process embodied in the strike committee, which can be viewed as an alternative “workers’ council structure [that] is ‘spontaneously’ generated because it immediately answers the organizational needs of grassroots struggle” (Cohen 2011, 48). What is necessary as a condition for working-class emancipation and the overthrow of the capitalist state is a well-rounded struggle that unites workplace and community struggles and overcomes the rifts between the economic, the social, and the political (Ness and Azzellini 2011, 7). The following section provides the context in which workers at Marikana went on strike in 2012 and again in 2014, highlighting the ways in which capitalist exploitation of workers has continued in the post-apartheid period, particularly in the mines.

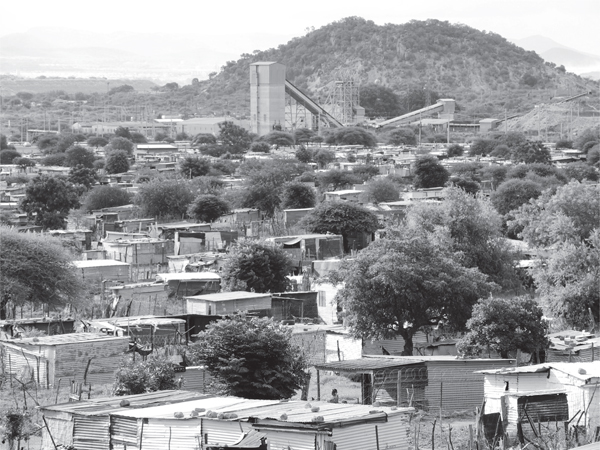

Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Thomas Piketty’s unlikely best seller analyzing growing inequality under capitalism, opens with a reference to the Marikana massacre. Despite some shortcomings in Piketty’s treatment of the event (see Alexander 2014a), he nevertheless sees Marikana’s importance as a symbol of the direct and tragic clash of capitalist and working-class interests in a global context where the rich are getting richer and the poor poorer. Neoliberal restructuring worldwide has led to workers losing many of the gains made in the postwar period. In a South Africa just emerging from apartheid rule and hardly recovered from it, workers had to weather the storm of the ANC government’s neoliberal economic policies. They won some rights, including the vote and the right to strike, but these newfound rights had hardly had time to make a difference before workers had to face the onslaught of privatization, outsourcing, labor flexibility, removal of exchange controls, and other neoliberal attacks (see Bond 2000; Terreblanche 2012). Soon post-apartheid South Africa became the most unequal country in the world. Unemployment went through the roof. Precariousness at work increased, and the cheap labor system fashioned under apartheid continued in mining and other sectors of the economy. Living conditions in working-class areas did not improve, with many workers forced to live in shantytowns that mushroomed for want of housing in the urban areas. Rustenburg, the capital city of platinum production in South Africa, has become the capital city of shantytowns.

Rustenburg is located seventy miles northwest of Johannesburg. Shack settlements pepper the landscape, often found next to mine shafts or adjacent to built-up working-class townships. According to census data, in 2011 the Rustenburg Local Municipality had an estimated population of 549,575, occupying an area of 1,322 square miles (Statistics South Africa 2011). Population growth there is higher than the national average, estimated to have ranged between 3.6% and 15% from the year 2000 to the present. This is due to migration by job seekers from within South Africa—only 7% of migrants originate from other southern African countries like Mozambique, Malawi, Swaziland, or Lesotho (Kibet 2013).

Poverty levels are high in Rustenburg, with 50% of the population recording zero monthly income, 11% earning less than R800, and 38% recording less than R3,200 (R1 is equivalent to about 70 US cents); only 64.7% of the eligible workforce is employed, mostly in the mining sector (Rustenburg Local Municipality 2011, 18). Other sectors of the economy are dependent on mining. The area grows good citrus, but agricultural activity “has been in constant decline due to pollution from mining processes” (Kibet 2013, 70). The termination of the apartheid regime’s subsidized regional industrialization program led to great job losses that were exacerbated by the mining sector’s adoption of flexible production systems.4 At the end of the 1990s the number of unemployed migrants swelled, with “100,000 living in informal backyard and shack settlements” (Mosiane 2011, 42). Rising poverty levels saw “the crime rate … increasing at a frightening pace” (Kibet 2013, 71). Rising unemployment levels have resulted in “an even more desperate reserve army of labour than in the early days of migrancy” (Forrest 2014, 161), creating conditions for the continuation of the super-exploitation of labor. The intrusion of labor brokers into the centralized employment system run by the recruitment company Teba, along with the increasing employment of locals rather than migrants and various other labor-cost-saving machinations on the part of mining capital, has resulted in “unacceptably low wages, poor conditions and low union levels [affecting] at least a third of labour hired by mines” (Forrest 2014, 165).

Since the end of apartheid and the growth of the unions, in particular the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM), there have been some major gains for miners in South Africa, including significant wage increases, better job security, and eradication of racist policies (Forrest 2014; Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu 2011). However, the mine owners have been reluctant to share their earnings with the workforce. The platinum boom of the 2000s brought enormous profits, benefiting shareholders and executives while labor received very little: “Between 2000 and 2008 workers at South Africa’s three largest platinum producers [Anglo American Platinum, Lonmin, and Impala] received only 29% of value added produced,” whereas on average during this period labor’s share of the value added in South Africa was about 50% (Bowman and Isaacs 2014, 5). The bosses have also sought and found ways to perpetuate the cheap labor system. Generally, “contradictions in the implementation of post-apartheid transformative legislation has resulted in a continued hyperexploitation of both local and non–South African labour” (Forrest 2014, 156).

The use of migrant workers continues to form the cornerstone of the cheap labor system, albeit with some changes (for example, there has been a shift away from employing workers from other countries).5 Central recruitment of labor has been modified, and the new order allows workers free movement and the ability to seek employment wherever they wish; this has tended, in the context of high unemployment levels and deteriorating economic conditions in rural areas, to ensure mining capital a steady and plentiful supply of skilled and unskilled labor, from which it can pull on its own terms. The power of capital over labor has also been increased by the move toward the use of labor brokers and contracting out in the employment of workers, which fragments the labor force into permanent and contract workers (Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu 2011). There is evidence that “mines use brokers for various reasons, an important one being to circumvent unions…. Brokers know that discouraging union membership is the key to sustaining low wages so that they can offer competitive rates to mines whilst securing their own profits” (Forrest 2014, 158). This has undermined labor solidarity and, together with the high competition for jobs, has rendered both groups of workers, permanent and contract, precarious given capital’s advantage in the situation.6

The NUM has responded ineffectively and sometimes badly to this threat of labor fragmentation. A 2004 report from the union secretariat (quoted in Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu 2008, 278) reveals that mid-level union leaders, when faced with retrenchments, use contract workers as sacrificial lambs to save union members. The NUM has only managed to recruit 10% of subcontracted workers, despite their increasingly high numbers in the sector (Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu 2008).

Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu (2008) have argued that the NUM’s success at recruiting workers in the apartheid era failed to translate into the new democratic order for a number of structural and political reasons. One of these was the new upward mobility of worker leaders: becoming a full-time shaft steward now meant a ticket to a high salary and an office job, which included being sent by the company to attend university courses. The bosses also started using shaft stewards as a pool from which to recruit foremen and managers. The practice over time has resulted in the union taking over or having an influence on recruitment processes. Such practices have in some instances led to corruption. The activities of the union leaders introduced social distance between rank-and-file workers and trade union leaders (Buhlungu 2010). Workers had to advance beyond the union to defend their own interests.

It was in the context of disillusion with the union that workers at Lonmin embarked on a strike without the blessing and against the advice of the NUM. Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu correctly identify the structural and political factors that lie behind this disillusion, including the real failure of the union to effectively defend the interests of workers. But they lack a unified concept that captures the essence of these processes. They correctly note how the union increasingly became a stepping-stone for would-be political and business leaders—with some, such as general secretaries Cyril Ramaphosa and Kgalema Motlante (and more recently Gwede Mantashe) becoming secretaries-general for the ANC and deputy presidents of the country, and some, like Ramaphosa and Marcel Golding, becoming billionaire business owners (Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu 2008). Other structural factors they mention as having eroded the old union solidarity are the demise of the hostel system, which had made it easy for the NUM to organize workers in their living spaces and had created the possibility of upward and occupational mobility, and the entry of women workers into the mining sector. What is unclear in their analysis is how the structural and political factors are related to each other. What is missing in their analysis, I submit, is the concept of the “politics of class collaboration” that informs the political and strategic choices and trajectories of the NUM leadership both in their day-to-day and long-term practice. As Martin Legassick (2007, xxvi) has pointed out, agency (that is, leadership and organization) is primary, because consciousness does not mechanically reflect the objective conditions. I will turn to this idea later in the paper, after dealing with the question of the conditions in which workers live and the spaces in which they organize.

“Ironically,” Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu (2008, 265) observe, “the hostel system that was used as a form of near totalitarian labor control [under apartheid] became the organizational fulcrum of many of the union’s activities.” This observation points to the importance of the workers’ living spaces and their link to the workplace in the workers’ struggle against the bosses. Because the workers were concentrated in single-sex compounds and hostels, sleeping and eating together, once the NUM had made inroads into the workforce and become a presence in these spaces, union mobilization, communication, and solidarity were greatly facilitated. Indeed, the hostels’ public address systems were used to call union meetings. This was an instance of union politics and strategy successfully turning on its head the mining bosses’ plan to suppress union organization and labor militancy through the totalitarian hostel system. Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu see the demise of the hostel system as giving rise to an organizing problem for the NUM because when workers moved out to live in the shantytowns and villages that surround the mines, “the task of mobilizing workers [was] no longer a simple matter of getting every worker out of his or her dormitory to the stadium to listen to speeches and participate in singing” (Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu 2008, 283). This observation suggests that the NUM might have taken shortcuts in its choice of organizing methods; it also reveals a privileging of structure over agency in the authors’ analysis. It is not primarily the hostel structure that explains the success or otherwise of organizing. This becomes clear when we consider that during the 2014 platinum strike the bosses could not (as they did during strikes in 1987 and earlier) use the devastating weapon of firing all the workers and closing down the hostels, thus forcing workers to go back to their distant homes in order to crush the strike (Allen 2005, vol. 3). The workers lived in the shack districts of Rustenburg and were able to remain close to the mines during the strike; their living spaces were outside the reach of the bosses’ power.

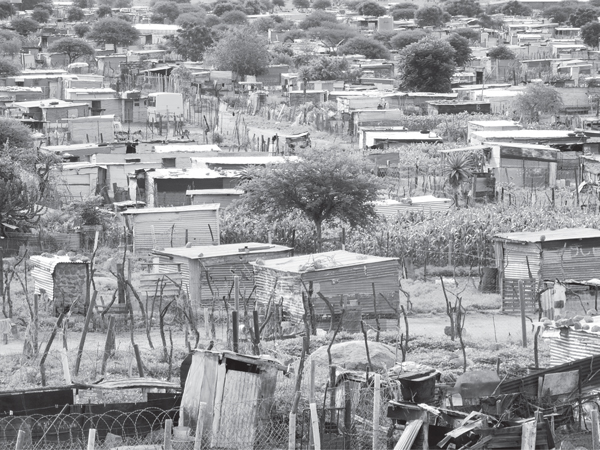

Nevertheless, the point above still underlines the importance of the workers’ living spaces. A consideration of workers’ lives in the informal settlements is important in understanding the Marikana massacre. The scrapping of apartheid’s influx control laws saw workers flocking into the towns and cities in search of employment and economic opportunities. The migration into Rustenburg put pressure on available resources in the town, especially housing: 17.6% of the population is officially estimated to live in the town’s twenty-four informal settlements (Rustenburg Local Municipality 2011).7 The desire for some control over personal space and the option to live with or be visited by kith and kin are the reasons why workers moved out of the hostels into the informal settlements. The mining companies agreed to pay a “living-out allowance” to compensate for the added expenses that workers took on when they left compounds where food and accommodation were subsidized by the employer. This “freedom” turned out to be contradictory in that many workers ended up using the allowance to supplement their meager wages, “cut[ting] their costs to the bone so as to save up money to return to their rural homesteads” (Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu 2010, 252). Greater freedom in fact was bestowed upon and enjoyed by the bosses, who through paying the living-out allowance thereby washed their hands of any responsibility for providing decent living conditions for their workers. The following description of life in one shack settlement in Rustenburg underlines this self-absolution by capital.

The settlement of Nkaneng, also known as Bleskop, is located southeast of Rustenburg on land that is zoned for “agricultural” use and owned by the Royal Bafokeng Administration.8 Nkaneng is Sesotho for “by force,” a reference to the establishment of the settlement by way of a land invasion in 1994.9 It is also called Bleskop because it is situated next to the Bleskop Vertical Shaft, which is owned by Anglo American Platinum (Amplats). The settlement consists of approximately four thousand structures and has an estimated population of 11,879, with most of the residents coming from the Eastern Cape (Rustenburg Local Municipality 2011). Very close to the settlement in a southwesterly direction is the Bleskop compound or hostel. The settlement is on flat ground to the west of a hill and is situated about two miles away from Photsaneng, a small, old, formal township that is partly controlled by the Royal Bafokeng Administration.

The settlement is poorly serviced, lacking electricity, proper sanitation, running water, and community facilities. The road infrastructure is poor, laid out in a grid format where each shack has its own yard. The shacks are mostly made of corrugated iron. Poverty and uncertainty about the future of the settlement discourage residents from using brick and mortar for building; there is a hope that the state will one day build houses for the informal settlement dwellers. Some shacks have ventilated pit toilets courtesy of a government project that ran out of funds before completion, provoking allegations of corruption. Water is ferried into the settlement. At certain times you can see residents queuing with their containers, waiting for the water truck. Several green, stationary water tanks are elevated above the ground and look over the settlement like giant sentinels; these are mostly locked. Privately owned bakkies (small trucks) roam the settlement’s roads selling water to community members. The advantage to that system is that you get the water at your gate. Since there is no electricity, people rely on wood, coal, and paraffin for their energy. At night it is very dark because there are no street lights.

There are no community facilities such as halls, sports fields, or parks. Community gatherings and meetings are held in an open space marked by a thorn tree in the midst of shacks. Church services are conducted inside people’s shacks (some are built slightly bigger than normal for the purpose). There are a few ramshackle general stores built from brick and mortar; there are numerous spaza shops in the form of shacks that have a big “window” on a side wall that acts as a counter. A handful of shacks housing small businesses (a hair salon, a tailor, a fruit stand) form a row on the settlement’s eastern boundary, across the tarred road that leads to the compound. During the 2012 strike at Amplats all the dozen business shacks located there were burned down, and these were the only ones that reemerged.

Many people entertain themselves by playing the radio, visiting each other, drinking in the local shebeens, or taking a walk across the railway line to Photsaneng, which has a motor vehicle service station, a money lending establishment, and a couple of shops that sell household items (meat and beer can be bought and consumed on shop premises). Boarding a passing minibus taxi takes you east into the city of Rustenburg or, if you like, west to the small town of Marikana, where there are more shops and a livelier hustle and bustle than in Photsaneng.

The people who live in the area represent a cross section of the working class. The majority appear to be unemployed, self-employed, and/or underemployed workers. Mine jobs are preferred, but the increasing use of labor brokers exposes mineworkers to precariousness (Forrest 2014). Unlike during the days of apartheid, “the informal sector is a dominating presence in the lives” of migrant workers today (Cox, Hemson, and Todes 2004, 12). Many residents can be regarded as migrants in that they maintain ties with their homes and families in the rural areas.10 However, many recent migrants have not been able to secure formal employment and find themselves “in an increasingly marginal position economically, reliant on informal activities, or on poorly paid and insecure work in the formal sector (e.g., security and domestic work)” (Cox, Hemson, and Todes 2004, 12). Most come from the “deep rural areas” where poverty levels are high and employment prospects slim.11 As a consequence, migrants find themselves engaging in a range of activities more accurately regarded as “livelihoods” than “employment,” the same activities that are “crucially employed by the majority in the global south to adapt to changing social and economic conditions” (Mosiane 2011, 39; Rakodi 1995).

It can be surmised that living in these terrible conditions provided some of the pressure and motivation that steeled the resolve of the striking Lonmin workers to fight to win and to the bitter end. It should also be noted that many miners maintain two households: one in the shack settlement, where they might be living with a wife or girlfriend or relative, and the other at the rural homestead where the extended family lives. This splits the wage two ways and across a wide geographical space. Some miners live with their children in the shacks while maintaining their rural homes for stability, loyalty, culture, and a place to retire. These ties to the rural home have sometimes confused theorists about the class identity of migrants. As it is usually articulated, the theory of modes of production suggests that the rural area represents a peasant way of life and as such is precapitalist in essence; the migrant thus “oscillates” between two worlds and two modes of production, feudal or tributary and capitalist (see Wolpe 1972). Recent Marxist analyses of this question differ with this interpretation and suggest that capitalism can and in fact always has used different forms of labor exploitation, cultural practices, and political arrangements, as long as these operate within its logic and are subject to its laws of motion (see Banaji 2010). The miners of Rustenburg are proletarians who must struggle to make a life in the context of a complex reality that is constituted by underlying processes driven by the uneven and combined development of capitalism (Ashman 2012).

Since informal settlements are invariably established without the state’s approval or support and often against its wishes, the inhabitants have to organize themselves in order to have basic services such as water and sanitation, and to maintain a semblance of order and peaceful social living. As a result, in almost all of South Africa’s informal settlements there are people’s committees. These are formed by the community independently of the authorities and can be regarded as “civic” in that they aspire to take care of the affairs of the community as a whole, claiming authority over the community and acting as a kind of improvised government. In Nkaneng, as has often happened in other informal settlements, it was the original people’s committee that helped establish the settlement through, in this case, a 1994 land invasion that was peaceful and relatively uncontested by the authorities. The land invasion coincided with the demise of apartheid and the extension of the franchise to all.

This first committee formed around the leader of the invasion, an unemployed worker called Cairo, and concerned itself with allocating stands and setting up a basic social and political framework for a new settlement. However, Cairo’s committee was soon displaced by a leadership drawn from among the employed miners that was known as Five Madoda, a civic structure or “vigilante committee” linked to the Mouthpiece Workers Union. The political contestation of workers’ residential space was linked to the struggle for power between this union and NUM; the NUM dominated the hostels to such an extent that in reality workers living therein had no choice but to join it. Five Madoda appears to have organized itself in the nearby Bleskop hostel, from which it took control of the settlement and became a sovereign civic authority. The new union was formed in 1997 and came to be recognized by the bosses as a rival of the NUM. Its rise happened during a time of confusion and turmoil at Amplats, which was caused by the unbundling of JCI (the parent company) as well as workers’ fears and their militant action to defend their provident fund benefits. The formation and growth of the new union was accompanied by violence in the platinum belt, including assassinations carried out in the rural areas of the Eastern Cape (Bruce 2001).

Self-organization and self-government in South Africa’s informal settlements during the 1990s—throughout the country a period of violent political turmoil related to the birth pangs of the democratic order—was often accompanied by violent contestation for control of these areas. The committee that took over in Nkaneng, the Five Madoda, was jealous of its rule, and residents were treated as subjects of the committee rather than of the state. For example, police were not allowed into the area; the committee dealt with all disputes and engaged in crime fighting. It also supervised small business operations in the area, including the shebeens. It is apparent that its rule was less democratic or benevolent than Cairo’s earlier committee (for example, curfews were imposed on the settlement).

This was a period when Nkaneng was experiencing rapid growth and the state had more or less thrown up its hands and left the informal settlements to their own devices, necessitating the construction of local power centers. Abuse of power, opportunism, and criminality increasingly characterized the rule of Five Madoda. The committee ran a people’s court and meted out people’s justice in the form of fines and corporal punishment. The Mouthpiece Workers Union also appears to have been led by unsavory characters who involved themselves in criminal activities, including corruption and instigating violence and murder (Bruce 2001).

The Five Madoda was violently driven out of the township when the power of Mouthpiece waned and the residents were at the end of their rope. The committee was replaced by a people’s committee that had started operating in parallel fashion during the Five Madoda era. This people’s committee, sometimes referred to as a “street committee,” seemed to follow in the Five Madoda’s footsteps in its muscular control of affairs in the settlement. It, too, focused on crime fighting and running a people’s court that later lost credibility in the eyes of some community members due to its alleged partiality and harshness, which included the use of torture. In light of this single-minded focus on security-related functions, some commentators have suggested that a “rural vigilante militarism” was imported from the rural areas and adapted into the life of some urban informal settlements by migrants (Bruce 2001).

Later, the security function was removed from the people’s committee and transferred into the Community Policing Forum, a state structure in which police and communities jointly fight against crime (Pelser, Schnetler, and Louw 2002). The street committee was later replaced by a ward committee, a state structure meant to afford residents participation in an advisory capacity in local government matters (Republic of South Africa 2005). Political parties, especially the ANC, now operate in the area. It is clear that the struggle to improve living conditions is often coterminous with attempts to impose law and order upon workers, and the forms of these impositions are dynamic and unstable.

In Nkaneng-Bleskop, an especially interesting development in community organization has been the rise of a type of committee that is based on homeboy networks, called iinkundla. It coexists with the ward committee, the ANC local party committee, and a Community Policing Forum. But recently iinkundla seem to be gaining prominence and influence beyond taking care of matters when someone dies and resolving minor disputes. In a by-election held in 2012 the iinkundla were mobilized to support an independent candidate against an ANC candidate when the local government ward councilor, who is directly elected, passed away. Higher structures in the ANC attempted to impose their own candidate on the local branch as a result of factionalism in the party. This provoked a rebellion in which the branch’s preferred candidate, the local chairperson of the ANC Youth League, put himself forward as an independent and won the seat from the ruling party. The iinkundla threw their weight behind the independent, who has subsequently joined the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) of Julius Malema.12

The iinkundla system originated in the rural areas of the Eastern Cape, where the chiefs hold court in their homesteads. Inkundla literally means an open space like a courtyard and has connotations of transparency or publicness of the proceedings taking place therein. It is here that decisions affecting the community or the chief’s subjects are made, and here that disputes are resolved. When crime fighting became a harsh organized response under Five Madoda and the civic committee that succeeded it, both of which meted out heavy-handed and sometimes arbitrary justice, people from the Eastern Cape began to use their homeboy networks as dispute resolution mechanisms and as a way of protecting their “homies” from falling into the jurisdiction of the committee courts. The idea was that the iinkundla would deal with the wrongdoing of people who came from back home in Bizana, Ngqeleni, Mount Frere, and other Eastern Cape rural areas, mostly in the former Republic of Transkei. This reversion to a rural, “traditional” form of organization and justice underlines the relevance of the rural in the urban and demonstrates the survival of cultural and juridical practices and values that belong to an earlier way of life or are associated with precapitalist modes of production. Are these people torn between the old and the new? Or are they comfortably semi-urban, living in the urban areas while maintaining an essentially rural or traditionalist value system?

The deployment of iinkundla networks to gain political support for the independent candidate suggests that these questions miss an important point. They are based on viewing the modern and the traditional in a dichotomous fashion—as if they exist in separate worlds and, when they do meet or coexist, operate according to different logics. This approach is consonant with a modernization-theory perspective. This theory sees all societies as moving from traditional to modern. Where traditional attributes exist, it is assumed to be only a matter of time before they disappear and are replaced by the new. The concept of articulation is deployed to explain the relationship of the old and the new in instances where these coexist. This approach is often found in early interpretations of the political economy of South Africa, such as Harold Wolpe’s “cheap labour thesis” (whereby two modes of production, the capitalist and the precapitalist, “articulate” in the form of the migrant labor system, thus realizing the superexploitation of labor). But if we view historical development as a multilinear rather than a unilinear process, then we will realize, as Banaji argues, that the laws of motion of the capitalist mode of production find ways of subsuming earlier economic and social forms into the logic of capital (Banaji 2010). Hence, the iinkundla system is not so much a return to the rural areas and traditional ways as the use and adaptation of these ways to new purposes in the city. Exactly how and why this happens are empirical questions that can best be answered through research guided by the correct theoretical framework; but first we must look at the other side of worker self-organization, which is organization within the workplace itself.

The most important thing about the Lonmin strike that precipitated the Marikana massacre is that it was led by the workers themselves and not their union, the NUM. Indeed, the NUM distanced itself from the strike and publicly condemned it. The workers refused to listen to the union’s admonitions, reflecting their distrust and unhappiness with the NUM and precipitating their break with it. Workers at Impala Platinum had been the first to embark on a strike that was hostile to the union, several months before the Lonmin strike. The Lonmin strikers formed a similar strike committee to lead and organize their action. They put forward the demand for R12,500 per month, which gained popularity among the workers. The strike that began as a rebellion of the rock drill operators (RDOs) soon spread, until it was supported by all the workers on the mine.

The strike committee was elected by the workers. It called regular meetings of the strikers, kept the strike together by instilling discipline and politics, and attempted to negotiate with management. Initially the strikers held their meetings at the company stadium next to the compound. Later, workers were refused access to the stadium and met at a sports field next to the Nkaneng-Wonderkop settlement or on the mountain where the shootings took place during the massacre. The move to the mountain was precipitated by a violent skirmish involving some strikers and NUM local leaders, after the workers marched to the union office. The mountain, because of its elevation, provided a better vantage point from which to observe attacks against the workers.

The story of the massacre has been told in detail in a book by Peter Alexander and a documentary film by Rehad Desai (Alexander et al. 2012; Desai 2014). Here I would like to note how the self-organization of the strikers before and after the massacre was surprisingly strong and resilient; the strike at no point showed any serious signs of flagging despite a relentless onslaught by the bosses and the state, who used a variety of tactics aimed at dividing and weakening the strike. The workers met every day on the mountain in the days leading up to the massacre and every day on the sports field after it. The impression I got when I attended one of these meetings—two days after the massacre—was of discipline, determination, and respect. Some leading members of the strike committee, such as Mgcineni “Mambush” Noki, the man with the green blanket, had died under a hail of bullets; new workers took their places. No one was allowed to wear a hat at the meeting, in deference to the dead. Yet the trauma of the massacre appeared to have only strengthened the workers’ resolve and increased their realization that unity was the key to victory.

Outsiders, including the media, were allowed to attend the general meeting and were directed to the committee if necessary. The meeting was already in session as we met with the committee itself on the edges of the bigger group, sitting on the ground in a small, tight circle to speak with the strike leaders. The strike meeting welcomed messages of support and encouragement and in this respect had to break its rules that prevented females attending and addressing the male gathering. There was a lot of singing when the workers came to and left the meeting in groups. Workers’ power was tangible in the very breath that we took.13

The full story of what happened during the massacre has yet to be told. The commission set up by the South African government has, after two years, completed its work and submitted its report, whose conclusions and recommendations have proven controversial (Alexander 2014). However, some facts seem to be indisputable: the police were ordered by the powers that be to violently crush the strike and proceeded to do this, hunting down fleeing workers like animals and shooting some who were cowering among the mountain’s huge boulders as they tried to hide from the police helicopters, armored cars, and sharpshooters. Some workers bled to death lying on the ground as the police kept medical help at bay.14 There was close cooperation and connivance between the state and capital in the repression of the strike; Lonmin lent its helicopter and jail facilities to the police. Evidence suggests that one worker was shot in the back by police at long range as he scrambled across a small stream in a desperate bid to escape; this evidence was not contested during the Farlam Commission hearings. On the day of the massacre, four mortuary vans were brought to the scene before it happened, together with thousands of rounds of live ammunition: the massacre was planned (Alexander 2014).

The strike went on for several weeks after the massacre before the bosses relented and granted increases of up to 22% for certain categories of workers. The demand for R12,500 (US$850) a month was not met, but it became a rallying cry in the wave of strikes that broke out in the South African platinum, gold, and coal mines for several months after the massacre. A strike broke out at Amplats, the biggest platinum mine, and it too was led by a workers’ strike committee. The workers subsequently joined the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU) en masse, deserting the NUM. In 2014, from their new home, they launched a five-month-long strike against all three platinum mining companies that involved 70,000 workers and demanded the R12,500. This time, the strike was conducted according to the regulations of the Labour Relations Act and as such was “protected,” with the bosses unable to fire the workers willy-nilly. By joining AMCU the workers sought the power and safety of the “union of the office,” the better to take forward the demands formulated during the struggles led by the “union of the mountain.” Even during the so-called wildcat strikes that first broached the R12,500 demand, and certainly in the course of the orderly five-month strike, relentless propaganda by the state and capital against the workers’ demands failed to suppress the solidarity that the broader working class felt with the strikers. The platinum strikers appear to have won the sympathy of millions and millions of ordinary workers by their struggle.

NUM leadership, including that of the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP), came out on the side of the police who shot the strikers. The strikers provoked the police, they said; the demand was unrealistic; the strike threatened orderly labor relations; and so on. A campaign of slander was waged against AMCU, labeling it a vigilante union that used violence to recruit (Tabane 2013). So Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu’s identification of structural and political factors leading to the decline of the NUM, and indeed of COSATU, misses a crucial point: namely, that it is above all the politics of class collaboration that explains the impending demise of these once-powerful trade union organizations. The hallmark of the politics of class collaboration is a lack of faith in the power of the working class to lead the struggle against the bosses and win. It is a failure to see workers as the embodiment of the solution to the problems of humanity that emanate from capitalism. Leaders of class collaboration tend to be enamored with the power of the bosses, and their bedazzlement blinds them to the power of the workers. They cannot see the gold under their noses, in their own meetings, down the streets where they live; they can only see the capitalists’ tinsel and be impressed by the high swivel chairs found in their boardrooms. They look for solutions everywhere except in the working class. Worker leaders unfortunately seek a path between the interests of the workers and the bosses, seeking accommodation between the classes rather than leading the struggle of oppressed against oppressor.

At the level of the state this politics takes forms like social democracy and Stalinism. The ANC government consists of social democrats, Stalinists, and neoliberals. In practice, the global economic crisis blurs the lines of demarcation between these political ideologies. The Stalinists and the social democrats seek a rapprochement between the bosses who benefited from apartheid capitalism and the workers who suffered under it. In this respect they disagree with the neoliberals, whose raison d’être is to trample on workers’ interests. At the workplace, union leaders have become adept at balancing the interests of the bosses with those of the workers—a futile exercise given the ongoing capitalist crisis.

Bezuidenhout and Buhlungu’s research, as noted above, suggests that the so-called understanding between the union and the bosses, on balance and over time, has served largely to undermine the NUM’s ability to defend and promote its members’ interests. This is the thing about the politics of class collaboration. One day it preaches wage restraint in the interest of profits and realism. The next it’s about supporting a capitalist government that is supposedly worker-friendly, and the day after that it condones a police massacre of workers on strike for a living wage. August 16, 2012, was just another day in the politics of class collaboration.15

The discussion of workers’ control at the workplace and in their living space raises a number of theoretical and strategic issues for the workers’ movement. First, there is a need to consider the alternative forms of political organization that the workers create. During revolutionary upheavals, soviet-type worker organizations, which often traverse industrial and residential districts, are formed by mobilized workers (see Barker 1995, 2008). However, as we have seen in the discussion above, it is possible in less revolutionary periods to identify two major forms of these organs of worker control and coordination of struggle: namely, those that operate at the workplace and those that operate at the living space. On the one hand there are workers’ councils and other autonomous self-management structures that have been formed primarily at the workplace, with the aim of workers taking control of production processes there (see Ness and Azzellini 2011). On the other hand there are the neighborhood councils, civic organizations, and other autonomous community-based structures that organize in the spaces where workers live.16 From a theoretical perspective, the latter have not been consistently approached as instances of worker control, probably because of the recognition that communities are likely to consist of different class elements and not just the proletariat. It is also the case that political parties have tended to occupy the political sphere in workers’ living spaces. Yet worker self-organization at the living space still has to be approached from a working-class perspective and be accorded its proper status and place.

Second, and more generally, there is the question of the unity of labor and community struggles. To what extent do worker-control structures that operate at the workplace and at the living space cooperate with each other? This is an empirical and a strategic question. Strategically, the strongest way forward for the workers’ movement is to unite the struggles at home and at work. Workers on strike need the support of their communities, including family, friends, neighbors, unemployed workers, youth, and so on. The workers’ social revolution is hard to conceive of without changes happening at both the workplace and the living space. What goes on at the living space is very important in building the movement.

The Lonmin strike received support from the residents of Nkaneng-Wonderkop. This was especially true after the massacre, when, for example, the women’s group Sikhala Sonke (Zulu for “we are all crying”) was formed to organize support for both the miners and their families (SAPA 2013). This organization wrote and performed a play that portrayed the Marikana massacre from the point of view of the miners’ families. The strike also had an impact on the local committees of Nkaneng-Wonderkop. The old people’s committee affiliated with the South African National Civic Organisation, like COSATU in alliance with the ANC, continued to operate but was eclipsed by a new civic committee that was directly linked to the strike. The local ANC party branch was overtaken by the United Democratic Movement, a political party whose base is in the Eastern Cape, and later and more decisively by the EFF. The ANC lost its popularity in this informal settlement situated next to the mountain where the massacre happened.

During the Impala strike there was also a lot of community support. Workers’ meetings traditionally held at the mine hostel were instead held in the local informal settlement, Freedom Park, because the bosses refused to have the meetings on company premises. The meetings became community meetings that local residents attended and so were drawn into the strike. More than in any other strike in South Africa in the post-apartheid era, the platinum strikes seem to have begun to bridge the gap between community and labor struggles.

The views and analyses presented in this paper take as their premise the assumption that the working class is the revolutionary subject—that is, workers constitute the class that has the organic capacity to lead the struggle for human emancipation (Marx 1844). This assumption seems to hold when we analyze what happened at Marikana: how the workers, on their own and without the support of their union, waged a struggle that shook the mining capitalists and made history. It is true that the Lonmin strike itself was the culmination of a series of struggles that signaled increasing combativeness in the working class. Several other important struggles preceded it. There was the burgeoning movement of community protests called “service delivery protests,” which steadily increased in frequency over the past decade (Runciman, Ngwane, and Alexander 2012). And in 2007 and 2010 there were two major strikes by public sector workers, the biggest in the history of the country (Ceruti 2011). The political message of these strikes to the millions of workers watching was that it is okay to strike against “your own government.” Marikana was, however, a turning point (Alexander 2013). It was a critical event and an encounter that provoked “new forms of consciousness and political imagination in South Africa.”17 After Marikana, the workers’ struggle will never be the same again.

The fall of the NUM as the majority union in the platinum mines (it lost tens of thousands of its members to the AMCU) had the consequence of eroding its power in COSATU, thus adding grist to the mill of unionists beginning to vocalize their doubts about the strategic wisdom of subordinating organized labor to the politics of the ANC-SACP-COSATU alliance. The National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa (NUMSA), the biggest union in COSATU, held a special congress in 2013 in which it decided to pull out of the alliance and withhold election support for the ANC. During the congress workers spontaneously and out of their pockets donated more than R100,000 to the Marikana widows in an emotional outpouring of solidarity.18 NUMSA has subsequently formed a united front that seeks to unite labor and community struggles and serve as a stepping-stone toward the formation of a working-class party (Ashman and Pons-Vignon 2015). Julius Malema was the first influential politician to offer a public pledge of solidarity with the Lonmin strike. He launched his party, the EFF, at the mountain where the massacre took place—a party that would dramatically change public views of the South African parliament and its political alignments.

Marikana gave rise to a new mood of defiance and determination among ordinary people in struggle in South Africa. Many land invasions and house occupations that happened in the period after the massacre were named Marikana: the occupation of government houses in Mzimhlophe, Soweto; the informal settlement born of a land invasion in Philippi, Cape Town; the informal settlement born of a land invasion in Tlokwe, Potchefstroom; and more. Clearly Marikana grabbed the popular imagination as a struggle that showed determination, steadfastness, and a willingness to risk all. “We are not moving here; they must kill us as they killed the people in Marikana” is a common refrain among workers in struggle at the workplace or living space. There is a new confidence and hope, a sense of doing things ourselves, a sense that through struggle victory is possible.

The country has seen an increase in the number of community protests, with these becoming increasingly militant in the face of a heavy-handed response by the police. The demobilization and demoralization that set in during the past twenty years of “freedom,” including the stultifying grip of the politics of class collaboration, is slowly being shaken off. Despite the separation between community and labor struggles, and the fact that these are as yet early days, developments suggest that the workers’ movement is again in motion in South Africa. The support that Lonmin and Impala strikers received from their informal settlement communities has planted the seeds for the unification of labor and community struggles. Working-class agency is in the process of being recovered, and the organic capacity of the working class, long suppressed, is being released.19

The working-class movement has two legs: struggles at the workplace and struggles at the living space. The Marikana massacre highlights the importance of self-organization at the workers’ living space. There is a real possibility of uniting labor and community struggles in South Africa and in other countries, and of forging a revolutionary workers’ movement that will lead society out of the morass of the current global capitalist economic crisis. The capitalist class has no solution for the crisis; their focus is on how to manage it, but they are not even in agreement about how to do this. The events at Marikana brought out the organic capacity of the working class. They instilled new hope and heralded a new confidence, giving birth to the Spirit of Marikana. It is this spirit that socialists must protect, nurture, and develop as we move forward, led by workers in struggle.

Above, Nkaneng informal settlement with Karee minehead in the background; below, shacks at Nkaneng informal settlement. (All photos for this chapter by Trevor Ngwane.)

Above, domestic scene at Enkanini informal settlement, Wonderkop, next to the site of the Marikana massacre; below, leaders of the community committee at Freedom Park informal settlement, Rustenburg