Mexico’s Popular Protests and New Landscapes of Indignation

Claudia Delgado Villegas

“This really is not a problem: in Mexico whenever a corpse is sought many others are found in the investigation.”

—José Emelio Pacheco

On September 26, 2015, the streets of Mexico City roared with thousands of protesters marching to the Zócalo, the city’s main square, to meet once again with the parents of the forty-three normalistas of Ayotzinapa who disappeared in the state of Guerrero in 2014.1 September 26 was declared as “The Day of Indignation.” Indignation, because—after a year of what has been publicly condemned as a crime of state and the worst massacre of students in Mexico since 1968—there has been no justice, only 365 days of mass protests demanding two things: that the forty-three normalistas be presented alive, and that those responsible be brought before the law.2

A full year has passed without justice. The parents of the forty-three missing students and of the three students killed on September 26, 2014, in Iguala, Guerrero, came back to the Zócalo—the country’s symbolic political heart—so that the government could hear them loud and clear: they have not forgiven; they have not forgotten. Those forty-three are their children, their boys, the parents said, and they will never give up on them: “We know the government knows where our children are … hence we mandate them to present our forty-three alive.”

“If the government thinks we are stupid, well, today we’re here to prove them wrong.”

“Here we are, after a year, all of us standing and we’re not alone.”

“We’re not afraid of the government’s threats.”

“We will give our own lives until we find our children.”

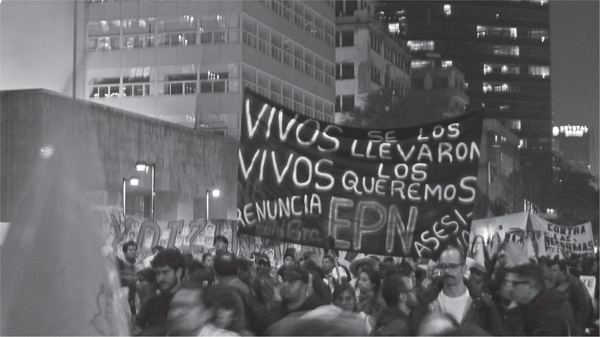

A year after the Ayotzinapa massacre, the motto “They were taken alive, we want them back alive!”3 echoes the logic of the worldwide popular mobilization around the forty-three disappeared students. The basic timeline of what happened on the night of September 26, 2014, has been read, seen, cried, discussed, and written ever since. There are very few in Mexico who do not know the story, or at least part of it, by now. It began when a convoy of normalistas was attacked and later kidnapped in the city of Iguala, about two hundred miles due south of Mexico City. Six people (three normalistas among them) were murdered. Guerrero state police, federal and military forces, and organized crime participated in the attack and the killings. The students were enrolled in the Rural Normal School Raúl Isidro Burgos, located in Ayotzinapa, a town about ninety miles from Iguala. The school is one of seventeen rural normal schools in Mexico.4 The normalistas were heading to Mexico City to join a demonstration for the forty-seventh anniversary of the student massacre of 1968, which is honored every year in the neighborhood of Tlatelolco.

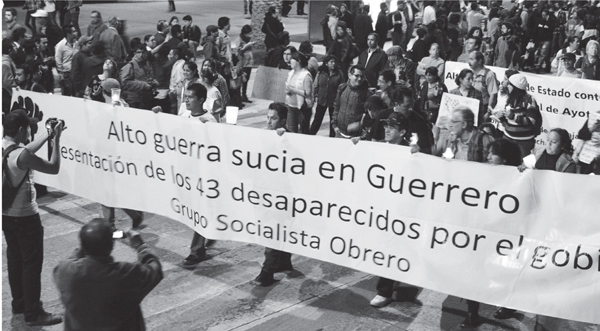

Hundreds of clandestine graves were found in Guerrero during the first year of deliberately ineffective federal and state investigations around the Ayotzinapa students.5 The first demonstration for Ayotzinapa took place in Guerrero’s capital city, Chilpancingo, three days after the massacre. An escalation of mobilizations, occupations, protests, and demonstrations in over twenty-five states in Mexico and hundreds of cities worldwide came after. A “global action day for Ayotzinapa” was called on the twenty-sixth day of every month for a year.6 The first demonstration in Mexico City happened on October 8, 2014.

A “National March for Ayotzinapa” was called for November 20 in Mexico City, to coincide with the anniversary of the 1910 Mexican Revolution. The protest marked the peak of the popular mobilizations for Ayotzinapa and thus contributed to defining the second decade of Mexico’s twenty-first century as an extraordinary period of social unrest and urban revolt. Protesters turned Mexico City’s urban heart into a cityscape of indignation.7 They took their anger to the streets to occupy and dwell in the urban space. They were a mass of outraged people using over two hundred years of political repertoire drawn from all the major revolts that had ever occurred in the Zócalo: there were impersonations of the priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, who led Mexico to independence in 1810; images of the Virgin of Guadalupe like the ones that accompanied him in the uprising; and banners showing Emiliano Zapata, peasant leader of the Mexican Revolution, or Che Guevara, or political slogans from the 1968 student movement, the Zapatistas of Chiapas (1994), or the peasants of Atenco with their machetes (2001).

In this playful exercise of keeping the talk of the streets alive, protesters found the means to effectively memorialize the nature of the times they are trying to change for future Tlachinollan generations. The most conspicuous examples included banners asking for the resignation of Enrique Peña Nieto from the presidential office—“Peña out!”8—and those denouncing the Ayotzinapa massacre as a crime of state—“The state did it!” The megaprotest of November 20 was organized to converge on the Zócalo from different starting points in the city. It moved in three caravans, each of them named for one of the murdered normalistas: Julio César Mondragón, Daniel Solís Gallardo, and Julio César Ramírez Nava. It took several hours for the thousands of protesters to finally reach the Zócalo.

In January 2015, Jesús Murillo Karam, then Mexico’s attorney general, aggravated the reasons for revolt when he informed the public that the forty-three normalistas of Ayotzinapa had been executed by the drug cartel United Warriors and their bodies burned in the Cocula municipal waste dump in Guerrero. He doomed himself by adding that these facts constituted the “historical truth”: meaning that the investigations and the protests should end, because the case was now closed. The government expected the parents to accept the reality of the death of their sons, period. An “anti-monument” with the number “+43” was built on Avenida Reforma in the seventh month after the massacre.9 Over 108 people had been detained by then, the majority of them members of the Iguala municipal police.10 The mayor of Iguala and his wife were arrested in July, becoming the first and only two public servants prosecuted so far. No federal forces or members of the army have ever been charged. On September 6, the so-called Interdisciplinary Group of Independent Experts (known by its acronym in Spanish as GIEI) submitted the “Ayotzinapa Report” to a government tripartite commission: the results of a six-month alternative investigation mandated by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, concluding that there was insufficient “scientific evidence” to show that the forty-three students were incinerated in Cocula.11 With this report, the parents said, the government’s “historic lie” was conclusively defeated by the truth.

On September 25, 2015, a day before the megaprotest called for the Day of Indignation, the parents of the normalistas ended a forty-three-hour hunger strike in the Zócalo: an hour for each of the forty-three missing, every hour representing their tireless struggle.12 Forty-three seats were placed for the press conference at the end of the collective fasting. The parents arrived at 2:00 p.m. sharp, walking out from the white tents of the small camp a few yards away. Their expressions were tired, worn, and humble. Many of them held their eyes downcast, yet they faced the hordes of cameras, reporters, and microphones. “We have hope,” they said, backed by a big white banner with the faces of the missing forty-three and the Amnesty International emblem. Words of hope were followed by words of outrage; each of the parents spoke of their own. The day before, the parents had met with Peña Nieto for the second time in a year. Their fury came from that doomed encounter too:

“We got nothing but lies from the president, and abuse from his presidential guards.”

“We’re angry because this government has done nothing but stab us in the heart.”

At the end of the press conference, one of the fathers spoke with me about the meaning of “indignation” and of summoning the outraged from the Zócalo. I recorded his words and later translated them into English:

For us, “indignation” is a word of respect and rage because we believe that all Mexicans and all human beings have a special place and that all of us are special. And when someone squashes our dignity as human beings, that makes us feel rage and demand that someone respect us; it is mainly a demand of self-respect. That is the meaning of “indignation” for us. We feel full of wrath because this government we have in Mexico believes that Mexicans are fools—that we believe whatever they say. We are angry because they believe we will remain silent, just because they control people through the television. But today we have shown them the dignity of the parents. This has been a year of relentless struggle and I think they will not stop us, despite the threats and all that we have been through this year; we will go on until we eventually find the truth.… For us, as the Zócalo is the heart of the city, and the city is the heart of this country in political, economic, and in all terms, we believe that’s the reason all eyes, all caring eyes, are looking to this place now, and that is why it is from here that the light of insurgency, the light of the discontent and protest, will shine on…. We hope that all Mexicans who have shown us their empathy and value each one of us [the parents], and especially those who feel our pain, we hope that they all take to the streets tomorrow, as will the rest of us. And we hope to hear a single cry: the cry for justice, and the presentation of the forty-three alive. But above all, we hope to show that together we are stronger.

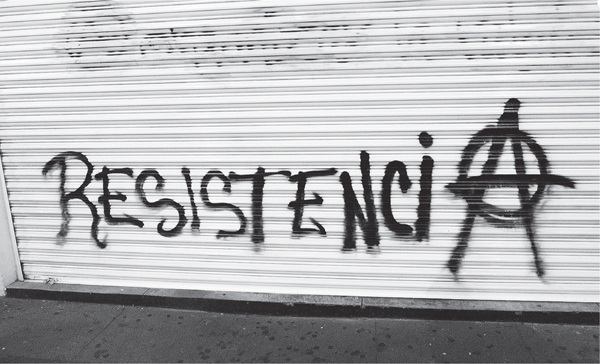

The Day of Indignation was gray and rainy. Once again, the parents marched through the streets of downtown Mexico City carrying 43 + 3 + 1 huge banners: forty-three prints of their missing sons, three for the students murdered in Iguala by police forces on September 26, 2014, and one for the activist Miguel Ángel Jiménez Blanco, who was assassinated in August 2015.13 The banners carried that day are the dreadful iconic image of Mexico’s present state of indignation, a state that (as I will show later on) has turned Mexico City into the city of indignation—a city of the outraged. But the Day of Indignation was also a day for the forty-three parents to share their learning and thank all those who, for an entire year, had not given up but kept assembling in the streets and everywhere else in support of their struggle: the normalistas of Ayotzinapa, unions, social organizations, peasants, students, youngsters, organizers, anarchists, teachers, mothers, fathers, sons and daughters, street vendors, street performers, indigenous people, intellectuals, feminists and women’s rights activists, LGBT people, advocates for human rights … the list goes on.

The parents thanked those assembled for having journeyed alongside them and asked us not to let them down. The names of the forty-three missing normalistas were read aloud by one of them at the +43 monument, one after another, followed by the chorus “present them alive.”14 After a couple of hours of slow walking—the pace due not to the exhaustion of the parents but to the packed streets—the megaprotest finally entered the Zócalo. This time, the stage for the grim political meeting had no roof and was only large enough to fit the forty-three parents: María de los Angeles. Rafael and Joaquina. Clemente and Luz María. Antonio and Hilda. Bernardo and Romana. Cornelio and María. Bernabé and Delfina. Margarito and Martina. Celso and Natividad. Francisco and Minerva. Leonel and Gloria. Margarito and Socorro. Damián and Dominga Antonia. Cristina. Ezequiel and Delia. Maximino and Soledad. José Alfredo and María Elena. Yolanda. Epifanio and Blanca. Ciriaco and Bernarda. Genoveva. Oscar and María Araceli. Israel and Ernestina. Nardo and María Isabel. Aristeo and Oli. Luciano and Eudocia. Carmen. Saúl and Nicanora. Santa Cruz and Abraham. Donato and Metodia. Macedonia. Lorenzo and Beningna. Francisco and Juliana. Joaquina. Eleucadio and Calixta. Estanislao and Margarita. Jaime and Inés. Nicolás and Marbella. Lucina and Juan. Celso and Micaela. Afrodita. Mario César and Hilda.15

The ones who spoke and the ones who listened dialogued the rest of that afternoon in the rain. One of the mothers spoke first:

Again we have shown the government that the people of Mexico are with us and haven’t left us alone. The parents are showing that the flame of indignation is still lit, that the flame of our anger is kindling. We have to punish this government because they are not going to do it themselves, and they are the only ones to blame for all that’s happening. The night of the twenty-sixth of September and the dawn of the twenty-seventh, the entire police force was involved; they all knew from 5:00 p.m. that the normalistas were going to Iguala. That’s why we ask Enrique Peña Nieto to leave, with his whole cabinet. He must return our children alive, so from here I say to him: “Don’t be an hijo de puta—you know where our children are.”

Another mother, an indigenous woman, spoke in her native language and translated her own words into Spanish:

To all those who raised their voices today, to all who did not stay at home, I say: today the sky is crying, because we have forty-three missing and thousands more. Today the sky weeps because of the missing students. Today I realize that our invitation was not in vain. We were heard. Today you took to the streets; today you walked together to defend our rights. To all those students who walked together with us, I say: this is the time to raise your voices, so that what happened to us does not happen to you, nor to your children or your grandchildren. It’s time to raise your voice and change this country. To change this government and not let them continue to rule. It is time now that no country, no indigenous people, should ever let another president take office. It should be every one of you taking the government, not them, not this government with their weapons. We as parents do not carry weapons, yet we are being blocked from passing through. They do not let us protest. As I told the riot police: “Who are you afraid of? Are you afraid of us? Are you afraid of the parents, of the students marching unarmed? Look at you: you have weapons, we don’t, and yet you’re afraid of us.”

Along with these women came the other parents. They spoke their own words, giving their faces, voices, and reasons to the same idea: “Neither the rain, nor the wind, nor the government—no one will stop this movement. We are all Ayotzinapa.”16 Meanwhile the crowd, sheltered by thousands of umbrellas, gave to the parents the cries of justice one of them had asked for the day before:

“No forgiveness, no forgetting, punishment to the murderers!”

“Urgent, urgent, the president must resign!”

“Not with tanks, not with machine guns, Ayotzi will not shut up! Not with tanks, not with machine guns, the people will not shut up! Not with tanks, not with machine guns, Mexico will not shut up!”

“Peña out! Peña out!”17

“It is raining rage,” read a small piece of blue cardboard attached to a Mexican flag. An older man carried it with his arms raised up. Maybe he was trying to make sure that everybody there, or anyone taking his photograph, could see the message and share it for the times to come. Maybe he was trying to stop the rain: the rain of rage his banner was referring to. Or maybe, like everybody else there, he was just trying to make sense of the student faces shown on those forty-three banners and the faces of the parents carrying them.

The morning of September 26, 2015, Mexican newspapers reviewed the most significant events in an attempt to make sense of the year that had followed the massacre of the normalistas. “Ayotzinapa, an open wound,” read a headline in La Jornada, one of the major daily newspapers in Mexico.18 Ayotzinapa occupied the front page along with news on Pope Francis’s visit to New York City, including his speech at the 70th General Assembly of the United Nations. The paper’s secondary news that day included the release of an official communiqué from the United Nations System in Mexico, ruling in favor of a “general reformulation of the investigation of the events in Iguala” and demanding “to clarify the irregularities [that have] arisen throughout the inquiries such as the use of torture to extract confessions, alteration of evidence, omissions and judicial deficiencies.” The day after that, the news reviewed all the major demonstrations demanding justice for Ayotzinapa, including the Day of Indignation and marches, rallies, and vigils in New York, Seattle, Paris, Madrid, Montreal, La Paz, Amsterdam, and Santiago de Chile, among other cities.

Trying to make sense of the major events that shape a country’s social history through the lens of news reports can be misleading, but it is worth doing in order to get a sense of the overall state of affairs in Mexico during the year that followed the Ayotzinapa massacre. Newspapers, like photographs, can capture a moment in time. I want to take advantage of this quality to make a brief journey through time and discover a more comprehensive framework for how affairs unfolded and the public responded during the year of indignation that began on September 26, 2014. I want to use it to reflect on the concrete conditions in which people are figuring out the potential of resistance and, ultimately, social change. In the months following the massacre, what did the front pages of La Jornada capture?

September 26, 2014. News of executions by the military reached the front page. These were not the executions of Ayotzinapa but of Tlatlaya, in Mexico state—the native state of Peña Nieto. The Mexican army had executed twenty-two people in the town of San Pedro Limón, Tlatlaya. News also referenced student conflict at the Instituto Politécnico Nacional, a major public university. Students were protesting against planned changes in the curriculum and internal regulations. The conflict started in mid-September, when the students declared an indefinite strike and closed down all the university facilities. Student demonstrations shut down the streets of Mexico City several times that fall.

The first news about the massacre of Ayotzinapa appeared a few days afterward, on September 28: “Police shoot normalistas in Iguala: 5 killed,” read a headline in the politics section. “Students report 25 injured—one of them brain dead—and an equal number missing.” “The body of a young man with signs of torture was found; PGJE [the General Judicial Attorney of the State of Guerrero] counted him as the sixth victim.” The same day, the economy section noted that the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean had issued a report pointing to the steep decline of wages in Mexico “to its lowest level in 40 years,” adding that in Mexican households “six out of 10 members live on less than $10,000 pesos per month”—that is, less than US$600.

November 26, 2014. The minister of the interior announced that for the government of Enrique Peña Nieto “Ayotzinapa is a priority, but we are attending to other conflicts too.” By then, news about US concern over Ayotzinapa had reached the front page: “US Senators concerned for the case of the 43.” “They urged Obama to offer support in the investigations.” So Ayotzinapa was now international news, alongside urban turmoil on the other side of the border: “The National Guard takes control of Ferguson.” “More riots across the US.” The paper reported protests in New York, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Chicago, Cleveland, Oakland, Newark, Atlanta, San Francisco, and Minneapolis, condemning a jury’s decision not to press charges against the white police officer who had killed Michael Brown on August 9.

January 26, 2015. Ayotzinapa was not much mentioned in the first month of the year, but the news on urban revolt worldwide kept coming. The front page informed of demonstrations against the so-called Public Security Act, promoted by Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy, attempting to amend the right to protest in Spain. In contrast, the streets of Athens were packed with supporters of Alexis Tsipras, leader of Syriza, who had won the Greek legislative elections and declared rejection of the austerity program imposed on Greece by the so-called European troika in exchange for bailout.

In the following months, updates on Ayotzinapa followed national and international concern for the deterioration of human rights in Mexico. There is a “before and after Ayotzinapa,” declared the president of the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) when giving his annual report (March 26, 2015). He described Mexico’s present situation as “the worst crisis ever” in terms of arbitrary detentions, forced disappearances, and torture. As the year continued, reports on the economic and social debacle happening in Mexico were as worrying as the ones on Ayotzinapa. “Concessions have 92 million hectares. Canadians dominate with 207 projects; have major deposits of gold. They are followed by US companies, China, Australia, and Japan” (April 26, 2015). A month later, economic news was not any better; headlines were as negative as the previous ones: billions of US dollars were being “injected into the market to stabilize the peso against the dollar.” “On Monday, for the very first time, the demand for dollars would not be fulfilled, and the Bank of Mexico placed only $30 million of the $52 million originally scheduled.” “The international reserve will keep going down until September 29” (May 26, 2015).

June 26, 2015. The annual US State Department report on human rights that became known in Mexico on this date noted “significant problems” in Mexico, “including the police and the army involvement in serious abuses, comprising extrajudicial killings, torture, forced disappearances and physical abuse.” There were additional concerns from civil society organizations like the UN and the CNDH on “poor prison conditions, arrests and arbitrary detentions, threats and violence against human rights activists and journalists, abuse of migrants, domestic violence, trafficking, abuse of disabled persons, discrimination against indigenous [persons], threats against lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender [persons], and child labor.”19

August 26, 2015. “Poverty unchanged for 22 years,” the paper announced, reporting the conclusions of the National Council for Evaluation of Social Development Policy (CONEVAL) on poverty in Mexico. Data showed the stagnation of family and per capita income from 1992 to 2014. The monthly family income in 1992 was Mex$3,500; in 2014, it was Mex$3,600. By then, the exchange rate was Mex$17.50 to the dollar, and Mexicans, according to data from the central bank, had transferred US$78 billion to bank accounts abroad or to business activities outside the country between January 2013 and June 2015.

September 26, 2015. The circle is complete. The journey through a year of indignation ends here. As mentioned at the beginning of this section, on the morning of September 26, 2015, newspapers included the remarks of Pope Francis at the 70th General Assembly of the United Nations in New York City. Curiously enough, he spoke of dignity, just as the parents of Ayotzinapa did in the Zócalo of Mexico City on the same day. His speech as head of state, making the fundamental connection between dignity and justice, was remarkably coincident with what the parents spoke of: how the Mexican state had trodden on the dignity of an entire people. No human individual or group must be permitted “to bypass the dignity and the rights of other individuals or their social groupings,” the pope said. Dignity must be built up and unfolded as a “collective right” and hence a condition that must come from the “limitation of power” by the law itself. Oddly enough, he made these remarks in the same room in which Peña Nieto was sitting at the UN. Peña Nieto had left Mexico in the middle of one of the gravest social crises in the nation’s history. He had preferred to ignore it—and yet he had to listen to it after all.

The popular revolt led by the parents of the forty-three missing students has everything to do with this universal sense of dignity. The parents themselves have put it that way. Yet, as I will show in the next section, the nature of this connection has deeper geographical grounds, arising to a great extent from the history of state violence in Guerrero, the home state of the normalistas and one of the poorest states in Mexico.

In the year since the massacre, the popular mobilization for Ayotzinapa has resulted in the escalation of state violence in Guerrero via increasing militarization and a new state security plan announced in October 2015. The strategy includes the substitution of federal forces for municipal police in twenty-two of the eighty-one municipalities in the state. The new police are under the command of the Ninth Military Zone.21 The involvement of both federal forces and the army in the massacre has been a major element in its public condemnation as a crime of state; hence, it is not meaningless to note that with this new plan Peña Nieto is moving the conflict back to square one by bringing the people of Guerrero more of the institutional violence at its origin.

The monopoly of this violence has been recounted many times and by many scholars throughout the twentieth century. The history of grievances is intense, long, and painful, and Ayotzinapa has brought back part of this social memory along with the whole legacy of contemporary popular protest stemming from resistance in the second half of twentieth century. This legacy has given Guerrero nicknames like “Brave Guerrero,” “Red Guerrero,” or “Red Territory” (Montemayor 1991; Bartra 1996; Illades 2012; González 2015). It reaches back to the militancy of the Mexican Communist Party, the foundation of the Federation of Socialist Peasant Students of Mexico (FECSM), and the opening itself of the Normal School in Ayotzinapa in the 1930s (González Rodríguez 2015; Tlachinollan 2015). These are major left, militant, and populist social institutions that were or still are active in local and regional politics. Lucio Cabañas and Genaro Vázquez are two of the most well-known figures due to their leadership in the peasant guerrilla fighting of the 1960s and 70s.22 These two emblematic social fighters, as it turns out, graduated from the Normal School in Ayotzinapa. “Maestro Cabañas, the people of Mexico miss you!”23

State violence hit the guerrillas in Guerrero hard during the so-called Dirty War in the 1970s and early 80s, a period that joined the annihilation of uprisings in the countryside with the repression of student, activist, and worker insurgency in the city. This was a period of well-documented involvement of government forces in the systematic repression of popular protest throughout the country. In the 1990s, the massacres of Aguas Blancas (the 1995 attack and killing of members of the Peasant Organization of the Southern Sierra by state police forces) and El Charco (in 1998, where a group of students were shot by the army, which alleged they were guerrilla fighters) turned public attention back to Guerrero and its long history of power abuses and impunity. And then again in 2011, the federal police killed two normalistas of the Ayotzinapa School during a peaceful student blockade of the Mexico-Acapulco Highway. The killings occurred under two of the most corrupt and repressive state administrations: the governments of Rubén Figueroa Alcocer (1993–1996) and Ángel Aguirre Rivero (1996–1999), both members of the Institutional Revolutionary Party—the party of Peña Nieto.24

Hernández (2014, 124) has analyzed the “political economy of abandonment,” arguing that “abandonment” is the language the Guerrerenses use to claim the history of social inequality and dispossession as well as the collective and individual inability to meet people’s basic social needs. The language can thus be used to probe the connections among the conditions of poverty, social misery, proletarianization, and the contemporary escalation of migration to the United States, as well as the extent to which these are the result of state actions. The importance of his analysis in the context of the present work lies in the possibility of framing a contemporary geography of abandonment that traces different “rounds of dispossession,” carried out through state actions to utterly maintain the long-term class and ethnic inequality of Guerrero, which relegates indigenous peoples to the very bottom of the social hierarchy.25 The inhabitants of these geographies are, drawing on Hernández’s words, people who live on the margins of the state.

The majority of the parents of the forty-three missing students come from within this geography of dispossession: towns like Ayutla de los Libres, Tixtla, Omeapa, Atliaca, Atoyac, Xalpatlahuac, Tecoanapa, Alpuyecancingo de las Montañas, El Pericón, Huajintepec, Arcelia, El Ticui, Juan R. Escudero, Cuatepec, San Cristóbal, Tlatzala, Zumpango del Río, Monte Alegre, Apango, La Montaña, and Malinaltepec. As one of them testified: “The majority of the students of the Ayotzinapa School are poor. Our families are poor, and our only chance was to study in the Normal of Ayotzinapa…. We are indigenous. Maybe that’s why today they want to get rid of us” (Imprenta de Luz 2014).

Hernández (2014, 147) describes the state of poverty in Guerrero as follows:

According to the [sic] Mexico’s Consejo Nacional de Evaluación de la Política de Desarrollo Social, in 2005 Guerrero has the second highest rate of Índice de Rezago Social (Social Gap Index). CONEVAL recognizes three types of poverty in the country: pobreza alimentaria (food poverty); pobreza de capacidades (capability poverty) and pobreza de patrimonio (patrimony poverty). The data for Guerrero (with a total population of 3,115,202) is as follows: food poverty, 40.2%; 50.2%, for capability poverty; and 70.2%, for “patrimony poverty.” According to the same source, in 2005 in Guerrero, 19.9% of the population 15 or more years old was illiterate; 7.1% of the population between 6 and 14 years old did not attend school; 58.0% had incomplete basic education; 74.1% had no access to the health care system; 31.6% of the dwellings had soil floors; 29.2% of dwellings lacked toilets; 34.5% had no access to water supply; 8.5% no access to electrical power; and 33.5% of the dwellings had no refrigerator.

In examining the role of the state in producing these local conditions of social vulnerability in Mexico, Robinson (2014) looks to the global scale to consider the role of the US in militarizing Mexico, and he analyzes this strategy as a counterpart to the capitalist globalization of the country. From this perspective, what happened in Ayotzinapa, rather than being considered an accident, must be understood within the context of the broad strategy of militarization that the United States has imposed on the Mexican government in order to protect the transnational corporate interests derived from NAFTA, Plan Mexico, and the Merida Initiative (and now, we might add, the Trans-Pacific Partnership). The United States, he maintains, “is just as much to blame as is the Peña Nieto and previous Mexican regimes for the grotesque crime in Iguala and for the reign of terror against the Mexican poor, the indigenous, and the working class. Plan Mexico has been funded with up to $3 billion from Washington. Steadfast U.S. support for one Mexican regime after another has helped contribute to the absolute impunity enjoyed by those who violate human rights, conduct forced disappearances and massacres, engage in wholesale corruption and violence on a daily basis.”

Paired with this large-scale perspective, González (2015) re-creates the contemporary social geography of Guerrero along three major lines: the waves of neoliberal reforms in Mexico,26 the state of “normalized” (systematic) violence, and the geopolitics around arms trading, drug production, and natural resources (mainly mines and gold).27 The latter involve US interests—and actual command over large parts of Mexico’s national territory. The local picture derived from this analysis describes a state of emergency in Guerrero due to structural violence,28 within an even larger state of “tolerated extermination” in Mexico due to the nationwide war on drugs: “The forced disappearances perpetrated by criminal groups, the military, the marines, and the police are another consequence of the war on drugs launched by the Mexican government, whose victims [may include anywhere from] … 70,000 dead and over 20,000 disappeared, according to the official count, to over 120,000 dead and disappeared, according to independent accounts. This is the grand ossuary the government insists on denying.” According to these data, an average of thirteen people have disappeared every day in Mexico since 2012 (González 2015, 51–52).

The Ayotzinapa massacre marks the pinnacle of governmental and social crisis in Mexico after three decades of NAFTA and the neoliberal labor and economic reforms of the administration of Peña Nieto. The technocracy in power is determined to increase poverty and inequality as it wages a war against the indigenous, the poor, and the working class. As we have seen, the state of Guerrero, the second-poorest state in Mexico after Chiapas and the home of the Ayotzinapa Normal School, remains a target of state violence and abandonment. Most of its labor force continues migrating to the United States, and people’s ability to meet their basic social needs is being reduced to smithereens, largely due to actions on the part of the state.29 If any conclusion can be derived from the foregoing analysis, it is the need to go further in examining the long-term connections between state actions and the origins of the Ayotzinapa massacre. Such a task surpasses the objectives of this work for now. Yet, as will be shown in the next and final section, there is another key bond behind this year of indignation and protests that needs to be addressed: the one connecting the mass mobilizations for Ayotzinapa to the rise of urban revolt.

Social crises in Mexico have so far gone hand in hand with a significant rise of urban protests. The protests for Ayotzinapa that shut down Mexico City’s downtown from the autumn of 2013 to the spring of 2015 are the latest in a series of mass mobilizations across the country. Since the insurrection of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation in 1994, these mobilizations have led many distinct movements for justice to the streets of Mexico City and—more remarkably—to the Zócalo itself. In 1994, the Zapatistas waged war against the Mexican state and were one of the first social movements to denounce neoliberalism as a system intended to annihilate human dignity. In 2001, they ended the “March of Dignity” in the Zócalo after years of sustained, peaceful civil resistance demanding the people’s right to land, work, housing, food, health care, education, independence, liberty, justice, and peace. These conditions, they said—and continue saying today—are nothing less than the primary conditions for anyone to live a life with dignity.

The mega-plantón (encampment) of 2013, held from May to September by thousands of dissident teachers from the national education workers’ union, will remain etched in the urban and social memory of Mexico City. For months, the teachers carried out demonstrations on the streets and occupied the 11 acres of the Zócalo with hundreds of tents, literally building up a city within the city to protest Peña Nieto’s education (labor) reforms, which had been approved in February 2013. With time their plantón grew to the point of actually becoming a sort of small town, with basic facilities, inhabitants, and a distinctive urban cultural and social rhythm.

Federal police destroyed the plantón on September 13, in order to have the space clean and ready for the celebrations of Mexico’s Independence Day on September 16. On October 5, one of its inhabitants said to me with a great sense of dignity: “Here is a sense of ownership; the government says it is theirs…. Well, we then also spoke and claimed a sense of ownership, but of people’s ownership. [The Zócalo] is ours, and the government has no right to take it away from us. When we say the Zócalo is ours, we are not saying that it belongs to the teachers, but that this is a place for social protest. That’s what we’re saying, that is why we have to return this space to the people.”

As much as they are echoing the rise of urban revolts all over the world, the social organization and militancy shown in the urban protests of the last two decades—from the Zapatistas to Ayotzinapa—are also indicative of an attempt to consolidate a class-based response to the particular social crisis being experienced in Mexico. On the one hand, an older generation of protesters takes inspiration from a lengthy tradition of hierarchical militancy in unions and urban social movements while a new generation of young urban protesters and social actors exercises more horizontal, multicultural, and self-managed forms of peaceful resistance. On the other hand, the protesters of these two generations have something in common: they are both addressing their call for social justice using strongly class-based language, and they are defending the people’s right to use and appropriate public spaces—like streets and squares—for social protest.

Marx and Engels stated in the Communist Manifesto that the history of all existing societies is the history of class struggle. This struggle passes through particular spaces and the political use that men and women make of them. All Mexico’s major political struggles have gone through the Zócalo, have assembled and rallied in the Zócalo, have spoken of justice from the Zócalo. The right to do so has been gained in the streets. Throughout postrevolutionary Mexico, most of the Mexican proletariat has converged in this space: teachers, electricians, railroad workers, and peasants. In 1938, the country’s sovereignty was symbolically defended against American neocolonialism in the Zócalo. On March 23, 1938, workers in Mexico City demonstrated in support of the presidential decree nationalizing the oil reserves. That day, President Cardenas stood on the balcony of the National Palace waving to protesters while a blanket hung on the facade of the Cathedral demanding the end of “capitalist oppression.” This was the same oppression that nearly a century before, in 1846, had marched with the firepower of the North American troops through Isabel La Católica Street to hang the American flag in the Zócalo. “To the Zócalo!”30 was the battle cry of the student demonstrations of July and August 1968, during which—for a moment—a red-and-black flag waved on the flagpole in the main square. The massacre of October 2 came after.

In 2014, the Ayotzinapa massacre once again took the struggle for social justice back to the Zócalo. Guerrero is a state with a strong heart and spirit of resistance, and the persistence and stubbornness of this spirit have contributed greatly to keeping the mobilizations for Ayotzinapa alive. But there is a deep historical connection between Ayotzinapa and Mexico City, and that connection passes through the production of space and its political use for social struggle. From this perspective, the urban protests for Ayotzinapa are as much about mobilizing people for justice as they are a battle for memory and belonging.

As public space, the Zócalo is a physical reflection of the struggle for inclusion in or exclusion from that “imagined community” (Anderson 1983) we call nation: that “illusory community” (Gilly 1997) formed by a superior and an inferior community linked by a relationship of command and obedience. If, in the construction of these imagined or illusory communities, history turns into an instrument for legitimizing the formation and continuation of these ties of command and obedience, then it is worth asking to what extent the urban protests for Ayotzinapa and the concrete ways we are memorializing it are challenging our ideas about this imagined community called Mexico. Whoever has the right to be in the Zócalo has the right to be in the city and hence has the right to be a part of the nation.

Last but not least, the Ayotzinapa massacre has quickened social protests from peaceful to more violent disputes for the public spaces that the local and federal administrations keep privatizing through major commerce, leisure, and consumption projects in the city. The dispute is generating a complex urban landscape of contestation: a cityscape of contestation. On the one hand, the city government struggles to comply with the neoliberal refunctionalization of Mexico City’s downtown as they push forward “touristification,” “thematization,” and gentrification projects, along with securitization and the enforcing of public order. On the other hand, the rise of popular mobilization against police repression and the abuse of state power is turning Mexico City’s downtown into a major arena of class struggle. The protests for Ayotzinapa are the continuation of this movement and hence an opportunity to change the city and the way we think about it.

In Mexico City’s case, the link between public space and urban protest is in harmony with the Global South’s distinctive notions of dignity and justice and hence provides a framework to examine new possibilities and reflect on the meaning of urban revolt. The city itself is becoming what Henri Lefebvre foresaw as a dimension of the possible: a means for spreading and practicing ideas of social justice.

(All photos for this chapter were taken during the demonstrations for Ayotzinapa in Mexico City, 2014–15, by Claudia Delgado Villegas.)