Chapter 9

Protecting Your Communications in Zoom

IN THIS CHAPTER

Understanding Zoom’s security problems and how the company responded

Understanding Zoom’s security problems and how the company responded

Configuring Zoom’s security settings

Configuring Zoom’s security settings

Authenticating users prior to attending meetings and webinars

Authenticating users prior to attending meetings and webinars

Keeping the Zoom desktop client updated

Keeping the Zoom desktop client updated

You may be familiar with the concept of a first-world problem. For example, say that you’re routinely bored at work. That’s frustrating, but at least you’re employed and collecting a paycheck. Hundreds of millions of other people can’t say the same thing, even in a good economy. They would love to have your problem.

Zoom has experienced an equivalent quandary. On one hand, its suite of tools allows hundreds of millions of people to communicate in a seamless way. To Zoom became a verb, the holy grail of marketing. It has helped solve or at least alleviate critical business and social problems, especially in the wake of COVID-19.

On the other hand, though, Zoom’s popularity has attracted plenty of flies in the form of bad actors. The situation forced its management to face some existential questions. What if organizations, school teachers, and other folks couldn’t secure their sensitive conversations from prying eyes, disgruntled exes, and black-hat hackers? What if any troll could show grade-school children pornographic images during a math class?

Without substantial safeguards in place, organizations and employees alike would be justifiably loathe to hop on the Zoom train. They would find alternative communications tools and, in due time, Zoom’s popularity would wane.

Fortunately, you need not abandon Zoom to secure your communications. You do, however, need to understand its most important security and privacy controls. And that, in a nutshell, is the objective of this chapter.

Putting Zoom’s Challenges into Proper Context

I’m a big fan of quotes. One of my favorites comes from the American historian and former Case Western Reserve University professor Melvin Kranzberg. Among his six laws of technology is the following: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral.”

If anyone has ever uttered a truer statement, I have yet to hear it.

Think about it. The rise of the web around 1995 birthed a slew of new industries, companies, and types of jobs. Before then, the idea of a web developer didn’t exist, nor did do-it-yourself (DIY) travel sites, such as Travelocity, Priceline, and Expedia. Good luck trying to find a social-media influencer or a YouTube celebrity in 1994.

Understanding creative destruction

Plenty of winners emerged from this era, but which formerly massive industries have suffered? How about travel agents, newspapers, 24-hour photo development shops, and bookstores? Automated teller machines (ATMs) meant that banks didn’t need to employ nearly as many tellers as they once did. The ubiquity of email resulted in far fewer fax machines. A few enthusiasts aside, typewriters have largely died thanks to computers, email, and word-processing programs.

It turns out that the advent of the web is just part of a larger trend: As technology creates some jobs, companies, and even entire industries, it concurrently destroys others. In 1942, the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter coined a colorful phrase for this phenomenon that remains popular nearly a century later: creative destruction. (See bit.ly/zfd-disr for a fascinating data visualization on how quickly successful companies have fallen from grace.)

Compounding matters further, the rate at which people adopt new technologies has been intensifying for decades, a trend that shows no signs of abating. (See econ.st/2KuPw9w for more here.)

Case in point: Consider Pokémon GO, an augmented-reality game for smartphones. In September 2016, Niantic released the app in collaboration with The Pokémon Company. Remarkably, just a few weeks later, the creators reported that people had downloaded the app more than 500 million times. Not long after that the number exceeded 1 billion.

Managing the double-edged sword of sudden, massive growth

Consider Amazon, Facebook, Google, eBay, Reddit, Uber, Airbnb, Twitter, Netflix, Craigslist, Nextdoor, and Zoom.

What do they all have in common?

Many things. Most important here, though, one is that their founders weren’t following tried-and-true playbooks that guaranteed success. That is, it’s not like these folks were starting Subway or McDonald’s franchises circa 2012. As such, they understandably failed to think about every possible use — and misuse — of their products and services along the way.

From the onset, it’s essential to understand two things. First, Zoom is a not fundamentally insecure set of communications tools. Second, it is not a repeat privacy offender à la Facebook, Google, and Uber. Still, Zoom’s unprecedented growth unearthed some fundamental issues that its management and software engineers hadn’t considered, much less fully appreciated. You may have even heard of the most severe problem that the company has encountered to date.

Zoombombing

I often draw analogies and use metaphors to drive home my points, especially between Zoom communications and their brick-and-mortar counterparts. Here’s another one.

Gordon is meeting with a group of Japanese investors in his office. Young buck Bud has weaseled his way into Gordon’s waiting room. (In case you’re curious, I’m referencing the 1987 film Wall Street. What can I say? I’m a cinephile.) After a while, Bud becomes impatient and storms into Gordon’s office. He starts screaming at Gordon about a high-stakes deal involving his father’s airline gone bad.

Think of Zoombombing as the digital equivalent of this scenario. Unknown and unwanted intruders entered countless Zoom meetings and started bothering participants and acting inappropriately. Think of it this way: For years, one of Zoom’s most valuable features was letting people quickly meet with others all across the globe. Within a few weeks, you could argue that that feature suddenly morphed into a bug.

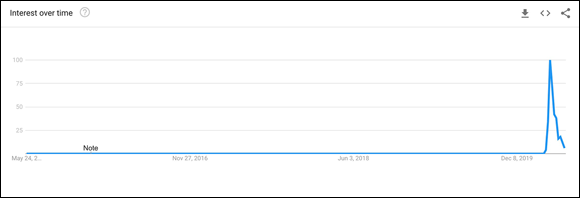

Prior to March 2020, the term Zoombombing effectively didn’t exist. (To be fair, though, trolls have long crashed many of the other videoconferencing tools that I reference in Chapter 1.) Don’t take my word for it, though. Figure 9-1 displays a Google Trends graph that proves my point.

FIGURE 9-1: Google Trends searches for Zoombombing over time.

General trends are certainly informative, but by definition they mask individual stories. Tales of rampant Zoombombing pervaded local and national media precisely because Zoom exploded. For example, on April 6, 2020, the New York City Department of Education cited Zoombombing in its decision to ban its schools from using Zoom for remote learning. A few days earlier, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) had issued a formal warning about criminals who were effectively hijacking classrooms across the country. A few litigious folks even filed lawsuits against Zoom.

In hindsight, the advent and rise of Zoombombing stemmed from several interrelated factors. I briefly touch on them in Chapter 1, but it’s critical to explain them more fully here.

By way of background, at the end of 2019, 10 million people regularly used Zoom’s suite of communication tools. As former Bloomberg Technology cohost Cory Johnson used to say on air, “That ain’t nothing.” The vast majority of these people qualified as enterprise customers. That is, they happily used Zoom to communicate with colleagues, partners, subordinates, vendors, job applicants, and other businessfolks.

Then, in late 2019, coronavirus shook the world.

Despite adequate time to get ready for the inevitable, relatively few American institutions and companies were prepared for the end of normal life as they knew it. On the business front, even retail behemoths Amazon and Walmart experienced significant problems meeting customer demand. For its part, Zoom suddenly had to deal with two interrelated issues:

- A flurry of new users

- Fundamentally different types of users than those from its existing customer base

There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen.

— Vladimir Lenin

It’s impossible to overstate the enormity of Zoom’s challenge. One day, Zoom supported 10 million people, almost all of whom were enterprise customers. A few months later, it was providing critical services to 20 times as many folks across the globe from all walks of life. Very few companies have experienced anywhere near that type of exponential increase in such a compressed period of time.

The qualitative shift in Zoom’s customers and users was just as important as the quantitative one, if not more so. The nearby sidebar serves as a reminder that enterprise tech and consumer tech are two very different types of animals, a fact that many people failed to appreciate.

Unfortunately, some of Zoom’s most vocal critics disregarded this critical distinction: The communication needs of large for-profit firms dramatically differ from those of school teachers, religious organizations, and the countless other decidedly nonbusiness groups that adopted Meetings & Chat in droves. Sadly, social media and outrage culture don’t lend themselves to nuance and facts.

Before detailing the specific changes that Zoom has made to date, it’s instructive to think about them in a different context. (For a car-related analogy of the daunting task that Zoom suddenly faced, read the nearby sidebar.)

Interestingly and as an aside, Zoom’s tools held up just fine as its user base mushroomed. That is, its suite of tools experienced only a few minor hiccups. This remarkable achievement is a testament to Zoom’s modern technological underpinnings. (For more on this subject, see Chapter 1.)

Gauging Zoom’s Response

Here’s the good news: Zoom’s management didn’t not pooh-pooh Zoombombing. On the contrary, its top brass took a number of immediate and bold steps to staunch the bleeding. It’s even fair to say that CEO Eric Yuan and company overcorrected. In this way, the company’s actions parallel Johnson & Johnson’s famous 1982 Tylenol recall, a case study that remains a staple in most MBA programs nearly four decades later.

On April 8, 2020, Zoom announced it had hired Facebook’s former security chief Alex Stamos as an advisor. (Read his Medium post at bit.ly/zm-adpt.) Zoom also formed a security council to carefully guide its eagerly awaited next steps. What’s more, Yuan began holding weekly “Ask Eric Anything” webinars — via Zoom, of course. He used that time to update customers, users, employees, partners, and investors on Zoom’s progress and future plans. Rare is the organization that responds to a crisis in such a rapid, consequential, and transparent manner.

As Stamos doubtless counseled Zoom’s head honchos, hiring consultants, hosting information sessions, and forming committees presented respectable initial responses. By themselves, however, words alone wouldn’t put Humpty Dumpty back together again. Zoom would have to act quickly to shore up its wares, restore trust, and change the narrative.

Zoom quickly proved that it was up to the task.

Exhibit A: On April 2, 2020, Zoom announced that it was enacting a 90-day feature freeze. (See bit.ly/zfd-freeze for more information.) In laymen’s terms, Zoom had suspended the development and deployment of new functionality. Instead, the company shifted its focus to making its existing tools and features as secure as possible.

Bringing Zoom’s privacy and security settings to the forefront

Less than a week after Zoom announced that it was enacting a 90-day feature freeze, the company started pushing updates to its desktop client and mobile apps that put security front and center. Along these lines, Zoom added a new Security icon to the desktop client’s user interface or UI. With a single click on its in-meeting menu, users could now access these essential security-related options:

- Lock Meeting: Prevent others from entering the meeting.

- Enable Waiting Room: For more information on this topic, see Chapter 4.

- Allow participants to share screen: Enable or disable this ability for all meeting participants.

- Allow participants to chat: Prohibit participants from exchanging text messages during the call or allow them to do so.

- Allow participants to rename themselves: As Chapter 4 details, both options offer benefits and drawbacks.

Zoom had already offered many of these features. The UI change made it easier for users to access them. Other enhancements, however, required much more than just hiding an important field from meeting participants and moving options around.

Enhancing its encryption method

Laypeople generally don’t know or care much about arcane security matters, such as application encryption. I certainly understand the sentiment, but I’d be remiss if I didn’t provide at least a little technical detail about this essential topic.

Zoom now secures its users’ video, voice, and text communications more securely than it has at any point in its history. Still, for the time being, Zoom falls short of the industry’s gold standard: end-to-end encryption or E2EE. As the nearby sidebar illustrates, tools that use this industrial-strength method restrict messages to only intended senders and recipients.

Waiting for E2EE

You may be wondering, “When will Zoom deploy E2EE?”

I’d bet my house that you’ll see it sooner rather than later.

As I did my research and wrote this book, two events in particular stood out that helped me read the tea leaves.

On May 7, 2020, Zoom announced that it had acquired Keybase, the maker of a niche chat tool lets its users easily and securely share messages and files. Critically, Keybase offered its users end-to-end encryption or E2EE. The timely Keybase acquisition marked the first one in Zoom’s storied nine-year history. (To read more about it, visit bit.ly/zfd-acq.)

In a related strategic move, consider what Zoom did on May 22, 2020. On that day, the company published its cryptographic design for peer review on the über-popular code repository GitHub. Put simply, Zoom’s management wants other techies, advocacy groups, customers, and academics to do the following:

- Identify any potential flaws in its proposed security framework.

- Suggest improvements.

Trust me: Rare is the company that does such a thing. (See bit.ly/zfd-crypt for more information about this topic.)

Protecting your devices and communications

Even when Zoom builds E2EE into its offerings, you can and should increase your security by doing one critical, simple, but oft-neglected thing.

Drumroll… .

I’m talking about regularly using a virtual private network (VPN) on all your devices. They are downright essential when connecting to public Wi-Fi networks at coffee shops, airports, bookstores, and gyms. VPN providers accomplish this task by rerouting all of their users’ Internet traffic through their own secure servers.

Enabling default passwords and waiting rooms for all meetings

Sure, Zoom has made a heap of critical product changes since March 2020. That’s not to say, however, that Zoom was the wild west before that time. On the contrary, the company had long provided its customers with ample security controls. For example, Zoom had long allowed its users to create passwords for each of the following meetings:

- Newly schedule meetings

- Instant meetings

- All meetings that participants joined via the host’s meeting ID

The rise of Zoombombing forced senior management to rethink its default meeting options. To this end, in April 2020, Zoom enabled passwords and waiting rooms for all meetings by default. Put differently, hosts now have to actively disable these features for their meetings.

Increasing the length of meeting and webinar IDs

In Chapter 4, I describe how you can give your PMI to a friend or loved one without much concern. For other types of meetings, though, you probably want to use a disposable, randomly generated ID number.

In April 2020, Zoom announced that those random numbers would consist of 11 digits — up from 9. Here’s some math to help you get your head around this change. There are now 100 billion different possible unique meeting numbers. Every person on earth could concurrently host 14 different meetings if Zoom ever allowed it. (Remember that you can host only one meeting at a time per account.) What’s more, Zoom tracks these meeting numbers and recycles them intelligently and in an attempt to minimize fraud.

Configuring Zoom for Maximum Privacy and Security

So far, this chapter has introduced Zoombombing and described how Zoom responded by overhauling its security and privacy settings. Kudos to the Zoomies for all of their hard work. The ones I know have been burning the midnight oil.

Now it’s time to shift gears and talk about you. What specific steps should you take to protect your communications in Zoom as much as possible?

- Keep Zoom up to date.

- Enable two-factor authentication.

- Authenticate user profiles.

- Intelligently use passwords.

- Follow Zoom’s best security practices.

- Use your brain.

Keeping Zoom up to date

Like just about every software vendor today, Zoom updates its products on a regular and sometimes weekly basis. (This reality makes writing For Dummies books especially challenging, but I digress.) To be sure, Zoom has followed this practice from its early days. Since March 2020, however, Zoom has increased the frequency with which it pushes new versions. A 30-fold increase in users in a matter of months tends to alter any company’s standard operating procedure.

At a high level, Zoom updates typically fall into the following five buckets:

- Changes to its user interface: Zoom modifies its menus, icons, navigation, and the like. Collectively, these tweaks affect how all users interact with Zoom. Because it does not want to confuse or alienate its users, the company does not shake things up too often and too drastically in this vein. Radical UI changes typically result in chaos and mass user defections.

- Improved or entirely new functionality: Zoom introduces an enhanced or brand new feature. For example, as Chapter 4 describes, Zoom didn’t always let users apply virtual backgrounds to their video meetings.

- Bug fixes: Zoom fixes a feature that should have worked from day one. Alternatively, the company triages a feature on a specific operating system, such as MacOS or Microsoft Windows.

- Security enhancements: Zoom understands both that hackers are a sophisticated lot and trolls are shameless. To this end, the company makes regular security-related front- and back-end changes to minimize the chance that bad actors wreak havoc.

-

Back-end or underlying code changes: In some cases, Zoom doesn’t alter what its software does as much as how its software does it. While invisible to users and customers, these types of changes can significantly improve how a program or application performs. (For example, consider Slack’s much-heralded 2019 application rewrite. Industry analysts praised its new version as much faster and resource-efficient than its predecessor.)

Software engineers refer to this process as refactoring. At a high level, although end-users ultimately perform the same tasks, the new code usually allows them to run in a smoother, more reliable, and more efficient manner than before.

Software engineers refer to this process as refactoring. At a high level, although end-users ultimately perform the same tasks, the new code usually allows them to run in a smoother, more reliable, and more efficient manner than before.

On occasion, Zoom may push a new version with a single and critical change or fix. The vast majority of the time, however, the company bundles a series of changes and goodies into a new release. In this way, Zoom follows the industry’s best practices.

Locating your version of Meetings & Chat

With rare exception, you should always use Zoom’s most current version. Fine, but how can you tell? Follow these steps to find out:

- Go to the Zoom desktop client and select the zoom.us menu.

-

From the drop-down menu, choose About Zoom.

Zoom displays the version number in a new window. For example, as of this writing, I am running the latest version of Zoom: 5.0.5.

- Click on the white Done button to return to Zoom.

Updating your software

Unless someone in your IT department explicitly tells you otherwise, update all Zoom tools to their most recent versions on a regular basis. Failure to do so robs you of new features. More important, lagging behind puts you, your colleagues, and even your entire organization at risk.

To update to the latest version of Meetings & Chat, follow these steps:

- Go to the Zoom desktop client and choose the zoom.us menu.

-

From the drop-down menu, choose Check for Updates.

Zoom informs you that you’re either

- Running its latest version; or

- An updated version is available.

Assuming that the latter is true, continue following these directions.

-

Click on the blue Update button.

Zoom begins its update process while a green progress bar steadily moves from left to right at the bottom of the screen.

-

Click on the white Install button.

Zoom displays a wizard similar to Figure 9-2.

FIGURE 9-2: Zoom installation wizard for Macs.

-

Click on Continue.

Depending on your computer’s settings, you may need to specify whether you’re installing Zoom for all user accounts or for only your own user account.

- Click on Continue again.

- (Optional) Change the folder in which you want to install the new version of the Zoom desktop client.

-

(Optional) Depending on your computer’s settings, enter your computer’s master password.

Don’t confuse this password with your Zoom one.

-

Click on Install Software.

Zoom completes the upgrade process.

- When finished, Zoom reverts to the desktop client’s user interface.

Dealing with forced upgrades

Despite the myriad reasons to upgrade their software and the ease of doing so, far too many organizations and individuals invariably forget to stay current — or actively resist doing so.

In response, software vendors occasionally compel people to upgrade to more current versions. Failing to move to a contemporary version may render the program inoperable. More bluntly, the old version stops functioning altogether.

The reasons for forced upgrades vary, but the usual suspects include when a company:

- Forgoes supporting a legacy technology

- Introduces key enhancements to its products

- Patches a critical security flaw

- Responds to new regulatory requirements

Again, Zoom plays by the same rules as most software vendors. For example, on April 27, 2020, Zoom released version 5.0 of Meetings & Chat. It included a slew of new security features, most notably enhanced encryption. (Read the release notes at bit.ly/zfd-new5.) At that point, the clock started ticking on its predecessors, specifically version 4.6.

As the nearby sidebar describes, running outdated software poses significant risks to all concerned.

Enabling two-factor authentication

There are two types of companies: those that have been hacked, and those who don't know they have been hacked.

— John Chambers

Say that you are one of the billions of Gmail or Facebook users. You may think that setting a complex password for each account guarantees that you and only you can access it.

And you’d be spectacularly wrong.

Black hats all too often pierce or circumvent organizations’ intricate security measures. In this vein, the quote from former Cisco Systems’ CEO John Chambers is spot-on. That’s not to say, however, that users and customers remain helpless against hackers. Nothing could be further from the truth. To that end, this section covers one of the most effective steps that Zoom users can take to protect their accounts and their communications.

Zoom is one of a boatload of tech companies that provides two-factor authentication, or 2FA. (Rare is the bank, social network, ecommerce site, or popular tech service that hasn’t offered this option for years.) In a nutshell, 2FA requires users to authenticate their true identities on a separate device — typically a smartphone. In so doing, 2FA provides users with an additional layer of security beyond their account passwords. In the event that hackers obtain users’ passwords, 2FA usually stops them in their tracks.

Activating 2FA at the organizational level

To activate 2FA for users under your organization’s Zoom account, follow these directions:

- In the Zoom web portal, under the Admin header, click on Advanced.

- Click on Security.

- Slide the Sign in with Two-Factor Authentication toggle button to the right so that it turns blue.

-

Select the checkbox to the left of the option that you want to enable throughout your organization.

Zoom provides three options:

- All users in your account: This self-explanatory option is also the most powerful. If you click on it, then also click on the blue Save button. If you select this option, then the next two are moot.

- Users with specific roles: Zoom lists its three default roles, plus any custom ones that you created. (See Chapter 3 for more detail on user roles.) By selecting desired roles here, you are requiring the members with these roles to set up 2FA.

- Users belonging to specific groups: Zoom lists the user groups that you have created. (See Chapter 3 for more information on this topic.) If you select a user group here, then you force all of its members to set up 2FA.

Congratulations. You have now required some, or even all, members in your organization to turn on 2FA. This move is wise. Still, specific users must activate it based upon your selection(s) in Step 6 in the preceding list.

Turning on 2FA for yourself

Your account admin or owner has enabled 2FA for your user group or even the entire organization. Now it’s time for individual users to set it up for their specific Zoom accounts. Pick up your smartphone, get your popcorn ready, and follow these steps to secure your Zoom account with 2FA:

- (Optional) Open a web browser, go to

https://zoom.us, and make sure that you’ve signed out of your Zoom web portal. -

Sign back in to your Zoom web portal.

Zoom displays a screen that walks you through the 2FA process.

-

Open the Google Authenticator app on your smartphone.

If you have not downloaded and installed this app, then do both.

Although the precise steps may vary, you can also use the Microsoft Authenticator, FreeOTP, and Authy mobile apps.

Although the precise steps may vary, you can also use the Microsoft Authenticator, FreeOTP, and Authy mobile apps. -

In the Google Authenticator app, click on the blue plus icon in the top right-hand corner of the screen.

You’re indicating that you want to add 2FA for another site, app, or service.

- Press Scan barcode with your finger.

- Point your phone at your computer until it recognizes the QR code.

-

In the Google Authenticator app, click on the blue plus icon in the top right-hand corner of the screen.

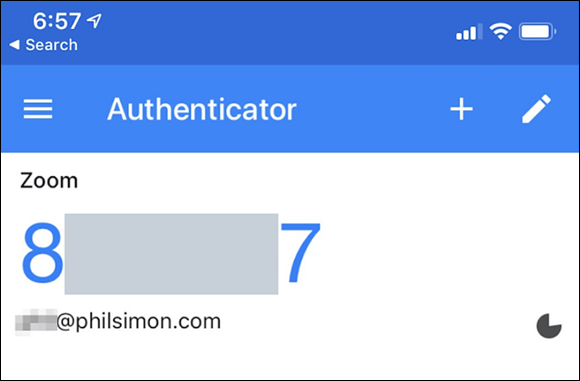

As Figure 9-3 displays, a six-digit verification code appears in your smartphone’s Google Authenticator app.

Note the timer in the lower right-hand corner of Figure 9-3. If it expires, then the Google Authenticator app automatically generates another six-digit code and resets the clock.

FIGURE 9-3: Partially redacted Zoom six-digit verification code in the Google Authenticator app.

- Returning to the Zoom web portal, enter the six-digit code from the app under the Enter the verification code header.

- Click on the blue Continue button.

You may already be using 2FA for other services, such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Gmail. If not, then you really should. For those of you who are curious about how 2FA works, the nearby sidebar provides a detailed example.

Remaining vigilant, even with 2FA enabled

Yes, activating 2FA adds some friction to Zoom’s sign-in process, but the juice is well worth the squeeze. You’ll considerably reduce the odds that someone hacks your Zoom account.

Note my phrasing in the preceding sentence: Reduce the odds. Lest you think that 2FA negates the possibility that hackers will be able to gain access to your account, be warned. Bad actors are devilishly clever.

Among the tools that hackers routinely employ in their attempts to circumvent 2FA is the SIM swap. (SIM stands for subscriber identification module.) They call phone carriers pretending to be you, often using data readily available on the Dark Web. Equipped with your mother’s maiden name, the make of your first car, your social security number, or just about anything else you can imagine, they call AT&T and Verizon. They are often able to convince call center reps to switch your phone number over a SIM card that they own and control.

Authenticating user profiles

Mary-Kate and Ashley are 19-year-old college students who decide to venture out to a bar one Friday night. At the door, a gruff bouncer asks for their IDs. The two try to flirt their way in, but he isn’t having any of it. He can see from their licenses that they aren’t legally old enough to drink. Mary-Kate and Ashley will have to try their luck somewhere else.

The preceding example is a decidedly low-tech version of user authentication. In a way, a bouncer verifying college students’ ages is the same as an enterprise system ensuring that a specific user can access sensitive employee and company data. Along the same lines, it’s not a stretch for Zoom to make reasonably certain that people are who they claim to be prior to allowing them to enter webinars and meetings.

Up until December 2019, Zoom provided some degree of user authentication, but not nearly the same level that it does as of mid-2020. Put another way, Zoom used to allow people to join meetings and webinars without formally authenticating users. In this example, Mary-Kate and Ashley would have had a better chance of pounding shots of whiskey despite being legally prohibited from drinking.

Zoom now allows hosts to restrict who can attend meetings in two ways:

- Users must use the email addresses tied to their Zoom accounts.

- Users can register only if their email address contains a specific domain.

For starters, Zoom requires owners or admins to enable authentication at the account level. Follow these steps to kick-start this process:

- In the Zoom web portal, under the Admin header, click on Account Management.

- Click on Account Settings.

-

Slide the Only authenticated users can join meetings toggle button to the right so that it turns blue.

Zoom displays a message asking you to confirm your decision.

-

Click on the blue Turn On button.

Zoom lets you know that it has updated your settings.

The first authentication option involves making meeting participants sign in to Zoom. Remember that, by default, Zoom does not require participants to have registered for Zoom accounts; they can join calls anonymously. (Forget about waiting rooms for the time being — a subject broached in Chapter 4.)

Enabling this authentication method means that only people with valid Zoom accounts can join your meeting or webinar. In other words, under this scenario, Zoom permits users to join irrespective of the email domains linked to their accounts.

Say that Elliot hasn’t created a valid Zoom account. (I’m referencing Mr. Robot here in case you’re curious.) Still, he discovers your meeting’s URL or PMI. In this example, when he attempts to join, Zoom displays the authentication message in Figure 9-4.

FIGURE 9-4: Zoom user authentication message.

Problem solved, right?

Not necessarily.

Within minutes, Elliot registers for a Zoom account with his Gmail address. He then attempts to join your meeting. Other than the waiting room, what’s to stop you from letting him in?

Absolutely nothing.

For this very reason, Zoom offers an additional and more powerful authentication option. The following example demonstrates the benefits of using it.

Say that your work at Spotify and you’re holding a sensitive company meeting. Maybe you’re finalizing Joe Rogan’s jaw-dropping $100-million podcast deal. You want to do more than just restrict participants to people who have created verified Zoom accounts. You allow people to join only if their Zoom accounts are attached to one specific email domain: spotify.com.

Zoom lets meeting and webinar hosts impose this more restrictive authentication level as follows:

- In the Zoom web portal, under the Admin header, click on Account Management.

- Click on Account Settings.

-

To create another authentication method, under Only authenticated users can join meetings, click on the white Add Configuration button.

Zoom displays the form in Figure 9-5.

-

In the first text field, enter the name of the custom configuration that you’re creating.

For example, I am calling mine Spotify.

-

Enter the email domain(s) that you want to approve in the Select an authentication method box or upload a comma-separated value (CSV) file in lieu of typing multiple domains.

Think of this list as a whitelist; only accounts tied to the email domains that you enter here can join your meeting or webinar.

Uploading a CSV file can save you a good deal of time and data entry.

Uploading a CSV file can save you a good deal of time and data entry. - (Optional) If you want to set this authentication option as your default, then select the checkbox.

FIGURE 9-5: Zoom form to create domain-specific authentication.

-

Click on the blue Save button.

Zoom confirms that you’ve successfully completed this process. Now, Zoom users won’t be able to participate in the meeting unless their accounts are tied to the email addresses that you specified. Zoom will block those who try.

Intelligently using passwords

As you may expect, Zoom offers a number of password-related protections:

- Set a password for an individual upcoming meeting.

- Set other password-related options for your Zoom account.

- Apply different security options for different user groups.

- Require more complex meetings and webinar passwords.

Setting a password for an individual upcoming meeting

George and Jerry are planning a meeting to discuss an idea for a TV show about nothing. It’s all very hush-hush. As the meeting’s host, Jerry should follow these directions to password-protect the meeting:

- In the Zoom web portal and click on Meetings.

- Click on the blue Schedule a New Meeting button.

-

Enter the information about your meeting.

Chapter 4 covers this topic in considerable depth.

- Select the Meeting Password checkbox and enter a password.

- Click on the blue Save button at the bottom of the screen.

Setting other password-related options for your Zoom account

Zoom allows people to use passwords in a variety of significant ways.

Follow these directions to invoke other password-related options:

- In the Zoom web portal, under the Personal header, click on Settings.

-

Slide the toggle button next to the password options that you want to enable.

Zoom provides the following password-related options:

- Require a password when scheduling new meetings: Generates a password when you schedule a meeting. Participants will need to enter the password to join the meeting. Note that this option excludes meetings held via users’ Personal Meeting IDs (PMIs).

- Require a password for instant meetings: Generates a password for your instant meetings.

- Require a password for Personal Meeting ID (PMI): Enable this option only for meetings with the Join Before Host activated or for all meetings using the PMI. Regardless of the one that you select, you’ll need to enter a password.

- Embed password in meeting link for one-click join: Appends a code to the end of the invitation’s URL that eliminates the need for attendees to use a password.

- Require password for participants joining by phone: Requires participants to enter a numeric password. If you created an alphanumeric meeting password, Zoom provides callers with a numeric version of it.

Zoom confirms that you have successfully changed that option.

Applying different security options to different user groups

Chapter 3 details the benefits of creating and populating user groups — a valuable feature for customers on premium Zoom plans. User groups allow organizations to easily apply, change, restrict, and lock a variety of different settings to different users. Customizing users’ security settings represents possibly the best application of user groups, as the following example illustrates.

Ricky, Shelley, Blake, George, and Dave sell residential real estate for Premiere Properties in Chicago, Illinois. (I’m alluding to the exceptional 1992 film Glengarry Glen Ross here.) When these five realtors hold Zoom meetings with their prospects, they sometimes forget to enable certain securing settings. Their inattention to detail rankles John, their nominal boss and the company’s Zoom account owner. For example, they schedule meetings without requiring user authentication. John wants to lock down their settings such that they can’t forget to do these important things.

John starts by creating a new user group called Realtors. He then places the five of them in it. Finally, he follows the following directions to customize the new group’s security settings:

- In the Zoom web portal, under the Admin header, click on User Management.

- Click on Group Management.

- Click on the name of the user group whose settings you want to change.

-

Under the Meeting tab, slide the toggle button next to the option(s) that you want to enable.

For example, some of the choices include requiring members of the group

- Use their PMIs when starting instant meetings or scheduling meetings

- Use a password when holding meetings via their PMIs

- Restrict their meetings’ participants to authenticated users

Depending on the option that you select or enable, Zoom may prompt you with a confirmation window asking you to confirm your choice. Alternatively, Zoom may display a message in green at the top of the screen that reads, “Your settings have been updated.”

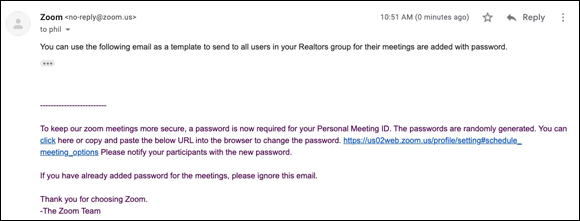

Zoom confirms your selection with an email similar to the one displayed in Figure 9-6.

FIGURE 9-6: Zoom email confirmation of new security settings for user group.

Here’s an example of this new security setting in action. John enables the Use a password when holding meetings via their PMIs setting for the Realtors user group. John notifies the group of this change in the #Announcements channel, but Shelley ignores it. He attempts to schedule a meeting with his prospects Bruce and Harriet Nyborg, once again without setting a meeting password.

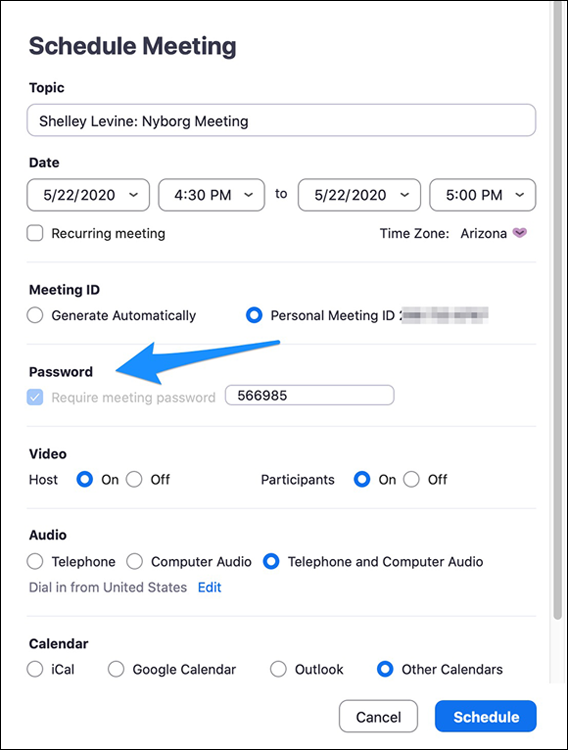

Shelley now has no choice but to use a password when he schedules a meeting. It’s a required field. As Figure 9-7 shows, Zoom won’t let Shelley uncheck the Password box. In other words, John has disabled all realtors’ ability to hold password-free meetings.

Requiring more complex meeting and webinar passwords

Generally speaking, people leave themselves susceptible to hackers in all sorts of ways. As but one example, the collective inability to understand — never mind follow — basic password protocols never ceases to amaze security experts. (Check out bit.ly/zfd-worst for a list of the 100 worst passwords from 2018. I’m sure that you can guess at least a few of them.) To nudge people in the right direction, many companies compel their users to create complex account passwords that include numbers, symbols, and/or minimum-length requirements.

FIGURE 9-7: Scheduling a meeting now that password field is required.

Zoom allows account owners and admins do the very same thing. That is, they can force members in their organization to create more intricate passwords for meetings and webinars in two ways:

- Mandate a minimum password length.

- Require all passwords to contain letters, numbers, and/or special characters.

To require members on your account to use strong passwords, follow these directions:

- In the Zoom web portal, under the Admin header, click on Account Management.

- Click on Account Settings.

- Click on Schedule Meeting.

-

Select the Meeting password requirement options that you want to turn on.

Your options here include

- Establishing a minimum password length (Zoom’s current maximum is ten characters)

- Including at least one letter

- Including at least one number

- Including at least one special character or symbol

- Only allowing a numeric password

-

After making your selections, click on the blue Save button.

Zoom confirms that it has successfully updated your settings.

Following Zoom’s best security practices

Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could they didn’t stop to think if they should.

— Jeff Goldblum as Dr. Ian Malcolm, Jurassic Park

As Chapter 4 describes, Zoom offers a bevy of robust features for meetings. (Short version: Thanks to Zoom, hosts and participants can perform many useful tasks.) There’s a chasm, though, between could and should. Put simply, just because Zoom lets you enable or disable a feature doesn’t mean that you should do it.

With that in mind, here are some tips on minimizing the chance that someone Zoombombs your meeting. More generally, follow the advice in this section to protect the privacy and security of your Zoom communications as much as possible.

Keeping your PMI private

Again, as Chapter 4 discusses, you wouldn’t give a stranger a key to your home. The same principles apply to your PMI. Giving it to your spouse or mother is benign. Sharing it on social media is a recipe for disaster.

Using waiting rooms

Yes, Zoom lets users with sufficient permissions disable waiting rooms for their meetings — and possibly for others employees in the organization. I’d advise against it, however, especially on a permanent basis. Visit bit.ly/zfd-diswr for directions on how to effectively make your meetings less secure.

Preventing removed meetings participants from rejoining

John is acting like a putz during the company Zoom meeting, a fact not lost on the other participants. You have warned him a few times to knock it off, but he’s incorrigible. As host, you finally boot him from the meeting. Everyone applauds.

By default, Zoom prevents John from jumping back in, even if he retained the host’s PMI or the meeting’s ID and password.

Again, depending on your formal Zoom role, you can change this setting. Still, I’d leave it as is. What’s more, if you’re a Zoom account owner or admin, then you may want to lock this setting such that non-administrative members cannot change it for themselves.

To do so, follow these directions:

- In the Zoom web portal, under the Admin header, click on Account Management.

- Click on Account Settings.

- Click on In Meeting (Basic).

- Slide the Allow removed participants to rejoin toggle button to the left to turn it off.

-

Click on the gray lock icon to the right of the toggle button.

Zoom displays a message asking you to confirm your decision.

-

Click on the blue Lock button.

Zoom confirms that it has successfully updated your settings.

Limiting who can control the main meeting screen

As Chapter 4 explains, Meetings & Chat offers a bevy of powerful screen-sharing features. If you want to dial back those options a bit, you certainly can. For example, say that you’d like to prevent participants from sharing their screens. Just follow these directions:

- Launch the Zoom desktop client.

- Start your meeting.

- Mouse over the bottom of the screen so that Zoom displays a menu.

- Click the up arrowhead (^) next to Share Screen.

- Select Advanced Sharing Options from the pop-up menu.

- Underneath Who can share?, select the Only Host checkbox.

- Close the screen and return to your meeting by clicking on the red circle in the top left-hand corner of the screen.

Using your brain

The history of technology teaches its students many important lessons. Perhaps at the top of the list is that even the smartest cookies cannot predict every conceivable problem that a software product, feature, or version may cause. First, the law of unintended consequences is alive and well.

Second and just as important, bad actors are a clever lot. They invariably employ sophisticated tactics to circumvent even the most thoughtful security and privacy controls. In this way, Zoom has had to confront some of the very same challenges that have plagued Facebook, Twitter, Google, Amazon, and other firms of consequence. All of this is to say that managers and software engineers can do only so much to mitigate the problems that invariably arise with massive usage.

At least you always take with you one of your most effective weapons to combat attendee mischief and malfeasance. I’m talking about the organ that lies between your ears. Think carefully and critically about what you’re doing in Zoom and with whom. Always be skeptical.

Exhibiting a healthy skepticism

Say that your son is a sophomore at a small northeastern university in a different part of the country. You and your spouse eagerly await your weekly Zoom call with him every Sunday afternoon at 4 p.m. You shared your PMI with him a year ago and thought nothing of it.

On Saturday, you receive an email from an unrecognized sender who purports to be your son. Still, something about the situation just rubs you the wrong way. This individual asks you to provide your PMI because he lost it.

What do you do?

Maybe nothing untoward is really taking place here. Maybe not. In this case, I would call your son or send him a text message explaining the situation. Based upon his response, your next step should be clear: Provide the PMI or report the email as the phishing attack that it appears to be.

Keeping privacy in mind during Zoom meetings

Regularly using your brain doesn’t just make it harder for hackers to wreak havoc; it can protect you from putting your foot in your mouth in front of others. Remember that meeting hosts can easily generate chat logs, subject to a few disclaimers. They just need to follow a few simple steps:

- Launch the Zoom desktop client.

- Start your meeting.

- Mouse over the bottom of your screen to invoke Zoom’s in-meeting menu.

- Click on the Chat icon.

- In the lower right-hand corner, click the ellipsis icon.

- From the prompt, click on Save Chat.

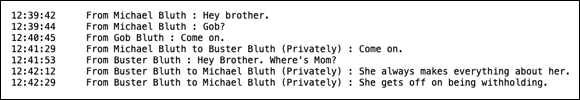

For example, Michael Bluth is hosting a meeting with his brothers Gob and Buster. During the meeting, at any point Michael can produce a chat log file because:

- He’s the meeting host.

- Michael has enabled participants’ ability to chat.

About five minutes into the meeting, Michael does this very thing. Zoom dutifully saves a simple text file to the default location on his computer. This file includes the following data from the meeting:

- All participants’ public chat messages

- Any private chat messages that Michael exchanged with Gob and Buster

- Any private chat messages that Gob and Buster exchanged with Michael

Michael’s log file looks something like Figure 9-8.

FIGURE 9-8: Zoom log file of chat activity during meeting.

Against this backdrop, keep the following privacy-related facts in mind as you use Meetings & Chat:

- Unless a host actively hits the Record button during a meeting, Zoom does not store video, audio, or chat content. That is, Zoom records nothing by default.

- When the host begins recording, Zoom provides both video and audio notifications to all meeting participants. If participating on a recorded meeting makes you uncomfortable, then you can always tell the host as much. You can also exit the meeting.

-

Think of each Zoom meeting as a quasi-private forum. If you want to slam your boss or mock your colleagues mid-meeting, then have at it. Zoom can’t stop you from exercising poor judgment. No tool can. Just remember that meeting participants are likely to notice inappropriate actions. When they do, prepare to suffer the consequences. In this way, Zoom is just like Slack, Microsoft Teams, email, and any other contemporary communications tool.

Whether you’re the host or not, think carefully about what you disclose both publicly and privately. There’s no guarantee that those messages from Zoom meetings will ultimately stay private. Say that you privately chat with colleagues, partners, customers, or other meeting participants. Someone could easily take screenshots of those private messages with a third-party tool and release them after or even during the meeting.

Whether you’re the host or not, think carefully about what you disclose both publicly and privately. There’s no guarantee that those messages from Zoom meetings will ultimately stay private. Say that you privately chat with colleagues, partners, customers, or other meeting participants. Someone could easily take screenshots of those private messages with a third-party tool and release them after or even during the meeting.

For more information on Zoom’s privacy policy, see bit.ly/zfd-priv.

Looking toward the Future

As I write these words, Zoom has nearly completed its self-imposed 90-day feature freeze. During this time, it has confronted a clear existential threat and made enormous progress. I’m hard-pressed to think of another company that has made such rapid, significant, and transparent changes to its product in such a short period of time — all while experiencing phenomenal growth. Brass tacks: Zoom’s current version (5.0.5) is its most secure yet. It has solidified the foundation of its products and paved the way for significant safety and privacy enhancements down the road.

It follows, then, that Zoom will never encounter another security- or privacy-related issue again, right?

Wrong.

I’m no soothsayer, but I do know this much: From time to time, every organization occasionally makes a blunder. I’m referring to both acts of commission and acts of omission. When any company drops the ball, the key questions to ask are

- How big is the gaffe?

- Whom does it affect, and how?

- What specific steps is its management taking to remedy the situation and prevent its recurrence?

- Did those steps ultimately work?

In the context of these questions, it’s impossible not to recognize and even applaud Zoom’s recent actions. Think about how it has responded to the legitimate security issues that prompted its 90-day feature freeze. Making the changes outlined in this chapter was no small endeavor. As someone who has studied consumer and enterprise technology for the last 25 years, I cannot recall seeing such decisive action and results from a software vendor under comparable circumstances. Zoom’s level of focus and execution put it in rarefied air indeed.

And I’m hardly the only person to take note. In fact, to say that many people noticed Zoom’s rapid response is the acme of understatement. Don’t take my word for it, though.

Early in this chapter, I mention that the NYC Department of Education banned teachers from using Zoom in their classrooms on April 6, 2020. Only a month later, the DoE reversed its decision. It determined that Zoom had fully addressed all of its security and privacy concerns. In fact, CEO Eric Yuan worked with the New York City school district himself. (See bit.ly/zfd-nyc2 for more details on this story.)

Zoom will forge ahead with impressive product improvements and valuable new features. Many of these updates and upgrades will rely upon cutting-edge technologies. (Chapter 13 describes some the specific ones that Zoom is using to enhance its offerings.) Expecting true product innovation from any company without the occasional bump in the road is a fool’s errand.

The April 2020 update also removed the Zoom meeting ID from the title toolbar. Some unruly meeting participants were distributing that number to uninvited guests.

The April 2020 update also removed the Zoom meeting ID from the title toolbar. Some unruly meeting participants were distributing that number to uninvited guests.