“I cannot recall, in my lengthy career, directing an actress so knowledgeable and yet so eager to learn as Florence La Badie. She was, at eight, a polished professional. At eighteen she was astounding directors and fellow performers with her instant memory of complicated lines and her ability to achieve near perfection at the first reading. And yet she at all times remained so down to earth and so completely approachable. Her death is a major blow to the world of theatre and motion pictures.”

(Actor-Director Chauncey Olcott, 1917)

Florence La Badie was seen on the world’s movie screens for less than nine years. But in that short period of time she became one of the most loved and respected actresses of the early days of motion pictures. Giants of the early movie industry, like Mary Pickford and director D. W. Griffith, called her the most talented actress they had ever worked with. The silent movie serial, The Million Dollar Mystery, in which she starred, is believed to have been shown in more movie theatres around the world than any other weekly serial of that era.

But when Florence La Badie died mysteriously at the age of twenty-four, six months after a “car accident” from which everyone thought she had recovered, the movie industry closed ranks and had few, if any, comments to make about the incident. Newspapers — despite being provided with information that her death was worthy of investigation — never printed a word to dispute the official report that said her fatal car accident was just that, an accident.

A story printed in the Boston Globe in 1927, ten years after the “accident,” questioned the accuracy of the police report of 1917. The writer wondered why no one had apparently been concerned when the car in which La Badie had the “accident” vanished mysteriously, only days after the incident, from the garage to which it had been towed. It was never recovered and thus never officially checked to discover if the “accident” might have been a deliberate attempt to silence Florence La Badie.

But the story brought no response from readers. If there was any interest aroused it was obviously not important enough for the story to be followed up in subsequent editions. Or, as one reporter believed, they had been told to drop the incident by people in high places. It was almost as though Florence La Badie had been totally forgotten in only ten years.

It was not until 1943 that actress Valentine Grant, wife of screen director Sidney Olcott and one of La Badie’s best friends, spoke publicly of her belief that La Badie’s death was no accident. But today, almost six decades later, the mystery is no nearer being solved than it was in 1917. Only speculation remains as to why her silence was perhaps very important to a person or persons unnamed.

Florence La Badie was born in Montreal, Quebec, on April 14, 1893. Her parents were among the upper class society in the city. Her father was a banker, her mother simply that, a woman dedicated to giving her daughter all the good things in life.

The good things included the finest education a girl could receive. The Convent of Notre Dame in Montreal was renowned for the quality of its graduates. Tuition was expensive but education standards were high. Along with her fellow students, Florence La Badie learned to speak English, French, and German fluently. Her future was expected to be the wife of a prominent Montrealer, her duties to raise a family to follow in her footsteps.

But Florence La Badie had other ideas. At the age of eight she gatecrashed an audition seeking a young lady to play a small part in Ragged Robin, a new play starring a distinguished actor-director of that era, Chauncey Olcott. There were more than 100 applicants for the part, but Olcott told the New York Times in 1917, the year of La Badie’s death, that once he had heard La Badie there was no further question who would get the role. “She was so natural that I was convinced she must have rehearsed the role before arriving at the theatre. I was puzzled how she could have done that because I alone had control of the scripts and not one of the auditioners had early access to the dialogue,” he said. “I learned later that she, along with the other auditioners, read the part only once, but that she had an uncanny ability to be able to memorize lines on sight.”

Olcott was somewhat surprised to discover that the eight-year-old had come to the audition alone. “Where is your mother?” I asked. “At home,” she replied. “Does she know you are here?” I enquired. “Of course not,” replied La Badie. “She has no idea that I plan to become an actress when I leave school.”

At that moment one of the mothers attending the audition with her daughter entered the conversation. “I know Florence,” she said. “She attends school with my daughter. I doubt very much if the school, too, has any idea she is here.” Florence unhesitatingly confirmed this suspicion.

“It was obvious that I had a problem,” said Olcott to the New York Times. “She was the perfect girl for the part but I had no idea if her parents would permit her to be in the play. The solution was to request the mother who knew her from the convent to go with me, and Florence, in my carriage to the La Badie home.”

The butler who answered the door at the La Badie mansion ushered them in to what Olcott later described as “a drawing room of such immense proportions that I could have staged even the largest scenes for any one of my productions there. It was truly magnificent. Mrs. Helene La Badie swept into the room with such grace that I knew immediately where Florence had learned her confidence and style. The lady who had accompanied us, a Mrs. Levesque, introduced us, and I told my story. I anticipated an uphill battle but had the shock of my life when Mrs. La Badie eliminated all further discussion after she had heard the basic details.”

“Then if my daughter wishes to accept the role in your play,” she said, “she has my complete approval.”

Olcott said he was, for a moment, stunned. Recovering from his confusion, he asked Mrs. La Badie what terms of salary would be acceptable. “You must take that up with the Convent of Notre Dame,” she said. “We would never think of accepting money for Florence’s services, but I think a contribution to the convent from your company would be a very satisfactory solution.”

Olcott never did say what sort of financial arrangement he made with the convent, only to comment, “I wish I had a manager capable of bargaining on my behalf as did the Sister at the convent.”

The La Badie family agreed to Florence being used in publicity for the play, and the story of her participation was a major news item throughout the play’s rehearsal period. “Florence was so good that I rewrote the script to make her role much larger than we originally intended,” said Olcott. “She knew every line after one reading and on stage you would have sworn she was a veteran five times her age.”

The play was a big success. La Badie’s performance was a triumph. “She upstaged me at every turn,” said Olcott, “and so totally stole the show that I took her hand in mine and walked with her in front of the final curtain after each performance. I am sure that ninety percent of the applause was for her, not for me.” Since forty-one year old Chauncey Olcott was a renowned and popular performer of that era, his statement was unexpected, but generous, and probably true.

Despite her instant success on stage in Montreal, Florence La Badie’s life appeared not to change. In a 1914 interview with Motion Picture World, when her fame as a film actress was at its peak, she said that “once the play’s run was over, I went back to my normal life as an eight-year-old learning how to be an eighteen-year-old.”

She produced for the magazine writer a scrapbook that covered her life from 1901 to 1908. Just a few months after her “professional” debut she was once more in the news. Her father, as a prominent banker in the city of Montreal, was chosen to host a delegation of German bankers scheduled to visit the area. La Badie, with her command of the German language, was named “official interpreter” for the party. At nine, she translated financial discussions with “total ease,” said a Montreal newspaper. Asked by the 1914 interviewer how she managed to deal with the technical aspects of the translation, she said: “You must remember I lived in a home where banking was the major topic of conversation, and I was never afraid to ask questions if I didn’t understand what they were talking about.”

She topped her achievement as a translator by playing the piano and singing — in German — at a banquet given to honor the visitors. Those present gave her a standing ovation, said the Montreal newspaper.

Another Montreal paper quoted one of the German bankers, Herman Kreiner, a director of the Berlin Opera House, as saying: “In Europe this child would be a sensation in the musical theatre. Here, I understand, she simply goes to school. I was instantly rebuffed when I suggested to her parents that she be brought to Europe under the auspices of my bank to make special appearances. This is a unique talent being totally wasted.”

Two days later, in the same newspaper, Kreiner apologized to the La Badie family for his unintentional and uncalled for intrusion in their private lives. But he added: “This must not be taken to retract my feelings about the remarkable talents of young Florence La Badie.”

By the time she was ten, La Badie had appeared as a singer, or pianist, or both, at many concerts in Montreal that were organized for charitable reasons. One of these appearances was with the visiting Philadelphia Orchestra, formed only two years earlier. The German-born conductor, Fritz Scheel, is reported as saying: “This child is already a musical giant. She must be permitted to attend the Philadelphia Academy of Music, where I can personally supervise her musical growth.” He also pointed out that her ability to converse with him in fluent German was “heart warming.”

Florence La Badie was reunited with Chauncey Olcott on March 17, 1905, when he returned to Montreal for a St. Patrick’s Day concert. Although he was renowned for his dramatic roles, Olcott had started his career with a “black-face” minstrel show in the 1880s, and for several years he was the leading tenor with the Duff Light Opera Company, singing the lilting melodies of Gilbert and Sullivan.

His love of Irish songs, inspired by his ancestry, led him to make many appearances singing ballads from the old country. The Irish musical play, Mavourneen, was written specially for him and St. Patrick’s Day was always of special importance in his life.

“He wrote to me some weeks before his arrival asking if I would sing some Irish songs at the concert with him,” La Badie told the interviewer. “I recall one was ‘My Wild Irish Rose,’ which he had made famous.

“During our morning rehearsal, a gentleman named Ernest Ball came to see Mr. Olcott and I could hear them discussing a song they had written together. They called me over and asked would I like to give the first performance of their latest song. I could accompany myself at the piano if I wished. I asked to hear it and Mr. Ball played it for me. I was enchanted and said ‘yes, please,’ I would love to sing it. So that night I introduced ‘Mother Machree’ to the world. The audience stood and applauded and I was asked to sing it twice more.”

There was a sequel to the Montreal concert, she told the interviewer. “In 1911, six years after the Montreal concert, I attended a matinee performance in New York of Barry of Ballymore, in which Mr. Olcott was starring. I was a little surprised to hear him sing ‘Mother Machree,’ which the program said had been specially written for the show and was being introduced to the public for the first time.

“I went backstage after the show was over and Mr. Olcott greeted me with warmth,” she recalled. “His wife, Margaret, whom I had met in Montreal, suggested that I join him on stage at the evening performance to sing ‘Mother Machree.’ They both remembered that I had introduced it in 1905 on St. Patrick’s Day. It was a remarkable evening. Although, of course, my face was by then well-known to moviegoers, and for more than a year my name had been used in film credits, on posters, and in advertising, nobody had ever heard my voice.

“Mr. Olcott introduced me to the audience and said that despite what the program told them I really was the first person to sing ‘Mother Machree’ back in 1905. He explained that it had not been used from that time until it was written into Barry of Ballymore.

“The reception was amazing. I almost wished I had continued with my singing when I heard the applause. I suddenly regretted the coldness of a movie studio where no one cared about my voice and there was no applause when a scene was ended.”

Florence La Badie had moved to New York early in 1908, one year after her father died from pneumonia in Montreal. “Mother and I had no financial problems,” she said. “Father had provided for us well, but we both wanted to get away from the city that held so many memories of him.

“We settled in New York because mother had two sisters living in New Jersey and one of father’s best friends was a Mr. Woodrow Wilson, who would become governor of New Jersey in 1910. They had first met at Princeton University where Mr. Wilson was the college president and my father was often a guest lecturer. And, of course, I felt that New York was where my future lay as an actress.”

Within a month of arriving in New York La Badie was working in the professional theatre. In an interview with the Motion Picture World she said: “We happened to bump into one of the cast of my first play in Montreal, Ragged Robin, and she said she knew of a young girl’s part in a play called The Blue Bird that would be perfect for me. Mother and I went to the New Theatre where auditions were being held and that same day I was hired for a six-week tour. Of course, mother travelled everywhere with me.

“My entry into the movies was really just as simple. Producer David Belasco, who saw The Blue Bird, asked if he could become my manager. Through Mr. Belasco I met Mary Pickford and her mother, and as Canadians we soon became firm friends. Mr. Belasco had sent her to the Biograph Studios, where she had soon made herself indispensable — that is Mary’s way — and she invited me to see her making a film. Before I knew it I was playing a very small role and within a week I was on the payroll of Biograph. It all sounds so easy, doesn’t it?”

Although, at first, movie-goers did not know the beautiful newcomer by name, since film companies were afraid to publicize individuals in case sudden popularity made them demand higher salaries, Florence La Badie soon became known to both movie-goers and avid readers of magazines and newspapers as the “Stanlaws Girl.” She earned this title when she became the favorite model of Penrhyn Stanlaws, then considered the finest still photographer in New York.

Glamorous pictures of her were splashed across front pages of magazines and newspapers. When her first film was released theatre managers took it upon themselves, much to the annoyance of the Biograph Company, to have stickers printed to paste over the posters saying the film featured the Stanlaws Girl, sometimes in letters bigger than the film title.

In 1909, when she joined the Biograph Company at $30 a week, the two most important actresses at the studio were Mary Pickford and a beauty named Florence Lawrence. “It didn’t take me long to realize that they were going to get all the best parts with the crumbs being thrown my way,” she told Picture Play in 1916. “I knew I had to go somewhere else if I was to achieve success, so when David Thompson, a casting director at Biograph, told me he was leaving to join the Thanhouser Company, based at New Rochelle, New Jersey, I eagerly accepted his invitation to move with him. Especially when he told me the owner of the studio, Edwin Thanhouser, had personally selected me from all the actresses at Biograph.”

When she arrived at the New Rochelle studio she found the company’s first priority was selling to the growing markets in France, Germany, and England. La Badie made a unique suggestion to Ed Thanhouser that made the studio the first to produce silent films in three different languages.

“Although, of course, there was no sound from the screens, I persuaded them to make three separate films, at least as far as my role was concerned. In each one I spoke my lines clearly into the camera in English, French, and German. Lip-reading was very popular among the deaf in that era,” she said, “so I wanted the watchers with that special ability to know exactly what I had said.”

David Thompson, who had convinced her to join the Thanhouser Company, was given the opportunity to become a director shortly after they both arrived at the new studio, and La Badie worked with him frequently until the end of her career. He confirmed her comment that she filmed the silent pictures in three languages.

In 1915 he told the Chicago Sunday Tribune that the company agreed to an unusual request by La Badie “because she rarely needed to do more than one take of a scene. To do three with her, each in a different language, was often cheaper than the five or six times they had to shoot scenes for other less competent actresses. It may sound strange to do silent films in English, French, and German, but we know it was appreciated and helped our distributors in Europe. We got a lot of letters from individuals who were astounded to find, when they lip-read Miss La Badie’s dialogue, that it was in their own language.

“Thanhouser’s French distributor sent us a large story from a major Paris newspaper telling of the satisfaction of the National Association for the Deaf, who were delighted to find that an American actress could actually speak French.”

Although La Badie had created a lot of attention in her short stay at Biograph, the studio had already given the title “The Biograph Girl” to another Canadian-born actress, Florence Lawrence. Many writers have suggested over the years that the first Biograph Girl was yet another Canadian, Mary Pickford, but she denied on many occasions that she ever used that title. So it was as the Stanlaws Girl that La Badie moved from Biograph to Thanhouser in 1910.

Later that same year, when Florence Lawrence was lured away from Biograph by Carl Laemmle to his new Independent Motion Picture Company of America (IMP), he decided to use her name in advertising since he couldn’t use the words Biograph Girl. That started the ball rolling. Biograph immediately put Mary Pickford’s name on their posters. And Thanhouser announced his Stanlaws Girl was, in reality, Florence La Badie.

At this point in the youthful history of the motion picture industry, the three highest-rated and best-known actresses, Mary Pickford, Florence La Badie, and Florence Lawrence, were all Canadian-born.

La Badie’s success story continued. In 1911 she made twenty films. In 1912 her total was no less than thirty-five. By 1912 her new contract with Thanhouser was for $160 a week. Mary Pickford, under contract to Majestic Films that same year, earned $275 a week. Pickford talked of those early days to Film Weekly in 1948. “These were incredible sums of money in those days,” she said. “We got together often just to talk about our good fortune.”

The occasional visits to the Thanhouser Studio by Governor Woodrow Wilson of New Jersey, which started in 1911 when La Badie arrived in New Rochelle, grew to be almost daily visits by 1912. Newspaper reporters who saw him there were told that movie making fascinated him. “But it was obvious to the film company employees that he was much more fascinated by eighteen-year-old Florence La Badie, the daughter of his old Canadian friend,” said Valentine Grant in 1943.

Grant recalled that the fifty-year-old governor’s visits became embarrassing to La Badie. “She told me it was a difficult situation to be in,” said Grant. “She didn’t want to offend such an important man who on many occasions gave approval for the studio to use government buildings for location shooting, buildings that were closed to other companies. And because he had been such a good friend to her father she accepted, with some misgivings, the gifts he frequently brought. They were never seen in public together but they often dined in private rooms down in the city. Florence was unhappy but was pressured by Ed Thanhouser to go along with the inconvenience for the good of the studio.”

In 1913, when Governor Wilson became President Woodrow Wilson he continued to visit La Badie at the studio as often as work permitted. “He told us on one occasion,” said Grant, “that as a former Governor of New Jersey he felt he had an obligation to come back to the state as often as possible to ensure nothing was being lost to New Jersey by his move to the White House. But we all knew he was really coming to see Florence.”

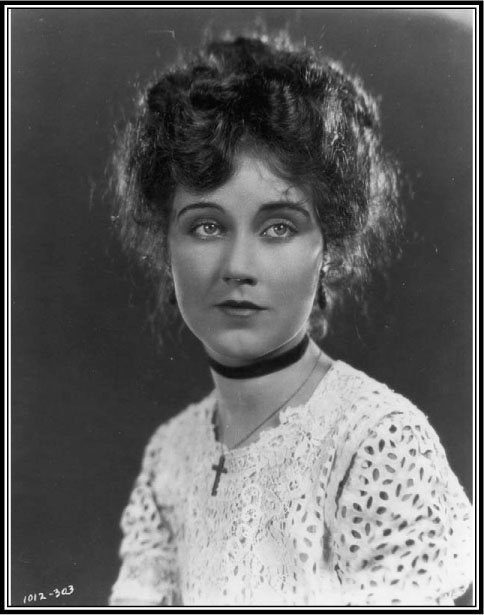

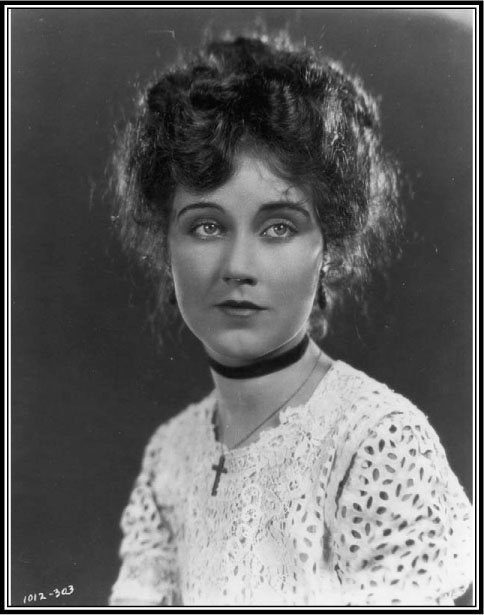

Florence La Badie

La Badie had her greatest success in 1914. Charles J. Hite, president of the Thanhouser Company, asked her to take the lead in a serial that would be issued worldwide to theatres in fifteen weekly episodes. It would, he pointed out, make her the first woman ever to be the star of her own weekly series.

She talked about the series in the Dramatic Mirror in 1914. “I really didn’t want to do it. I was afraid of overexposure, but James Cruze, who was also to be in the series, convinced me,” she said. “I valued his opinion and said ‘yes’ to Mr. Hite if the studio would make all the sets closed to all visitors so we could keep the endings of the unusual stories a closely guarded secret.”

“This may have been her story to the newspapers but she told me quite clearly that this was the only way she could hope to keep the President of the United States from constantly slobbering over her and pawing her,” said Grant.

The series, The Million Dollar Mystery, was proudly announced in trade magazines and news releases as Thanhouser’s most important production of the year. Hite signed the best supporting cast possible. In addition to James Cruze he hired Lila Chester, Frank Farrington, Marguerite Snow, and Sidney Bracy. “Florence read some of the stories and began to be enthusiastic about the series,” said Grant, “and the freedom from the president for three months was like a ton of bricks lifted from her shoulders.”

Each of the segments of the Million Dollar Mystery was a complete ten-minute movie with a continuing theme that was not resolved until the final episode. La Badie was the heroine of each episode with Cruze, Snow, and Bracy playing the same characters each week. Different actors of repute were added in each episode to play her rescuer or the villain.

At the start of the fourth week of shooting Ed Thanhouser surprised La Badie by bringing to the set a youthful but distinguished looking gentleman. “I would like you to meet your leading man for this week’s episode,” he told La Badie. “May I introduce His Grace, the Duke of Manchester, an important member of the British peerage. I must stress that at all times he must be referred to as ‘Your Grace.’” “Then you had better get me a new leading man,” said La Badie. Turning to the duke she said, “Don’t you have a first name?” “Of course,” he said, “it’s Robert.” “Then welcome, Robert, to the Thanhouser Studio,” said La Badie. “Let’s start rehearsing.”

La Badie told Picture Play in 1916 that the duke was a delight to have on the set. “Although he was not a great actor he was willing to learn and I spent hours with him going over the range of expressions he would need for the camera,” she said. “As far as I know it was the only film he ever made and it brought us a lot of publicity in the world’s newspapers. I should mention that he spoke French fluently and we were able to add his role in French to our releases for that country.”

But the duke and La Badie did not confine their get-togethers to the studio. Night after night they were seen in fashionable restaurants sitting, as the gossip columnists reported, “as closely as was allowable while preserving the correct decorum.” The “romance” blossomed for about four weeks before the duke sailed for home.

“Did you have any communication from him after his return to England?” asked the Picture Play reporter. “No,” said La Badie. “But I did have a letter from his wife telling me she had no intention of divorcing her husband. Good heavens, I had no idea he was married!”

Grant said she always believed La Badie’s public display of affection for the duke was intended to be “a message for the president.” But when President Wilson’s wife, Ellen, died in August 1914, Grant said La Badie told her that her days as an actress were very nearly at an end. “I know the president will not allow me to continue working in the public eye,” she said. “I believe he wants to marry me!”

“Closing the Million Dollar Mystery sets to visitors displeased the president,” recalled Grant. “The studio suddenly found its requests to use government buildings for location shooting were refused and police officers constantly harassed Thanhouser film units working in public parks or on streets where traffic was disrupted. Ed Thanhouser finally had to plead with Florence to make an exception to the closed set rules and admit the president so they could get the permits they needed. Florence relented, reluctantly, and her problems began again.”

In early 1914 La Badie had two books of poetry published, one of which, Thoughts of a Young Girl, became a bestseller. “People would bring copies to the studio and wait outside for her to leave so she would autograph them,” said Grant. “She would talk to them for an hour if the president was anywhere around. She discovered that by having lots of people around she could drive the president away from the studio. Even though his wife was no longer alive, he was reluctant, so soon after the funeral, to risk gossip that might defeat his chances of re-election in 1916.

“Quite by accident, she found another very effective way of keeping the president at arm’s length. Helen Badgley, a four-year-old from New Rochelle who was appearing in a number of Thanhouser films, took a liking to Florence who, in turn, delighted in keeping Helen fascinated with some of the ghost stories that came easily to her creative mind. Helen told her friends, and it was arranged that up to ten could visit the studio each day at noon and four in the afternoon so they could listen to Florence. It was great publicity, and also a perfect screen to keep the president away. Parents came along with the young children and — presumably — the president feared that parents might talk. She kept this up until the end of 1914.”

In June 1914 she is reported by the New York World to have spearheaded a drive to raise funds for the illumination of the Statue of Liberty. The newspaper said: “Miss Florence La Badie, ‘The Million Dollar Mystery girl,’ led a cavalcade of cars from Broadway and Sixty-third Street to the United States sub-treasury on Wall Street. She drove in her new ivory white Pullman coupe presented to her by the Thanhouser Company in recognition of her services to the company and the motion picture industry.”

At the treasury she was met by hundreds of bankers and brokers who had agreed to promote the illumination fund among their employees and customers. La Badie gave a speech from the steps outside the treasury. “It is of great importance to our nation, in this time of war in Europe, that we display our willingness to accept the world’s refugees by lighting up the Statue of Liberty as a signal of welcome.”

The report said that thousands of school children, given a day’s vacation to join the demonstration, joined her in singing the United States national anthem. But if the drive to raise the illumination money succeeded, no subsequent stories in the World announced the fact.

During the early summer of 1914, a major story in the nation’s newspapers told of the search for a missing four-year-old boy, Jimmy Glass. The child had vanished from the garden of his parents’ home in New Jersey. The hunt to locate the missing boy came close to home for La Badie when someone reported to the child’s mother that a person resembling the boy had been seen at the Thanhouser Studios.

It was October when New Jersey Police Lieutenant James P. Rooney, accompanied by the boy’s mother, arrived at the studio with a warrant to check the company’s files for the home addresses of every young person used in a Thanhouser film during the previous six months. La Badie heard of Mrs. Glass’s visit and invited her to her dressing room while the police did their routine work. So fascinated did she become with the story that she asked to speak to the police officer about the case.

Next day, the following comment, made by Lieutenant Rooney, was printed in the New York Telegraph: “The actress lady [La Badie] just took me off my feet,” he said. “Ideas just seemed to pop out of her head like gun flashes, every one of them a peach. She certainly is going to help us in a mighty big way.”

One of La Badie’s ideas was to send a sketch of the missing boy, done by a studio artist, along with every reply to the mounds of fan mail that came into the studio daily. With the sketch was a small poster offering $1,000, which La Badie guaranteed, to the person giving information that led to the recovery of Jimmy Glass.

La Badie’s two friends, Mary Pickford and Florence Lawrence, asked that they too be allowed to send out the information in their mail. Each added an additional $1,000 to the reward offered. In October 1914, The Moving Picture World estimated that more than 2,000 pieces of mail containing the missing boy’s description left the three studios every day.

Hundreds of leads arrived at the studios and police departments in more than twenty states and four Canadian provinces followed these up. Unhappily, the boy was never found.

“Early in December, Florence and her mother, Helene, received invitations to spend Christmas in Washington at the White House,” said Grant. “Of course, the studio was delighted, they visualized great publicity possibilities, but Florence was terribly upset. She, and her mother, discussed the situation with Ed Thanhouser, who told them the invitation could not be turned down. He said it was an honour they couldn’t refuse. Florence was so upset that she begged time off from the studio until the new year. It was obvious to all of us that she didn’t want to go to Washington, and she came to our home on several occasions and did nothing but cry all evening. She told us she was afraid of the president.”

But there was no way out. La Badie and her mother were chauffeured to Washington in a limousine sent by the president. Much to their disgust, the studio had been refused permission to use the story in any publicity plans.

“When she came back to the studio, in January 1915, we were all shocked to see that she was a changed person,” recalled Grant. “She refused to say a word about her visit to the White House, and even a mention of Washington sent her into crying spells. She spent hours alone in her dressing room and didn’t seem very interested in any of the films she was making. She only made four films in the first three months of the year before requesting a six-month leave of absence, which Thanhouser approved and announced to the newspapers.

“She didn’t say goodbye to any of us and when we tried to reach her by phone at her home on Claremont Avenue, overlooking Riverside Drive, in New York City, we were always told she was not well and wished to be left alone. My husband [Sidney Olcott] and I were away for several months around that time on location shooting in Florida so we knew little of what was going on until we returned in late June.”

Newspaper writers who enquired were told she had been given time off as she was suffering from a nervous breakdown. Even writers who had known her well received the cold shoulder when they tried to contact her at home.

Early in 1916, while the Olcotts were once again in Florida filming, La Badie returned to the Thanhouser Studio as though nothing had been wrong. James Cruze, who joined the Kalem unit in Florida, said she apologized to all the crew and cast for her unfriendliness earlier in the previous year. She explained that she had been working too hard and that the breakdown and her behaviour were a direct result of that overwork.

Thanhouser officials were glad to see her back. They took out full-page advertisements in the trade papers to detail her film schedule for the year ahead. Within a few days she was hard at work again. She made five films in the first three months of 1916 before once more complaining that the workload was too heavy and she once again needed a rest.

In April, Thanhouser officially announced La Badie’s retirement. “She will spend a few years travelling to other countries,” said the official news release.

Nothing more was heard from her until April 1917, when the New York newspapers printed details of a car accident in which she had been involved. The New York World reported that “Miss La Badie was driving down a hill on the outskirts of Ossining, a small community near Westchester, New York, when the brakes apparently failed on the vehicle and she was thrown out of the car when it overturned at the bottom of the hill.” The story continued: “A male person in the car with Miss La Badie was seen to jump out during the car’s wild run and was apparently unhurt. He has not yet been located or identified.”

According to the story La Badie was taken to the nearby Ossining Hospital but was not considered to be in serious condition. “She is expected to leave the hospital within a few weeks,” the report concluded.

The Olcotts immediately phoned the hospital and asked for information on La Badie’s condition. “She is doing very well,” said the nurse who was attending her, “but it will be some time before she can have visitors.”

“Since we couldn’t see her, Sid and I wrote her a long letter and took it, along with a large bouquet of flowers, to the hospital,” said Grant. “We hoped perhaps the doctors might relent and let us see her, but we got no further than the reception desk.

“We were puzzled as to why her mother hadn’t contacted us, and try as we may we failed to reach her. Ed Thanhouser seemed reluctant to talk about Florence. When the subject got around to her accident he always excused himself from the discussion.”

The flowers the Olcotts delivered were never acknowledged by La Badie, and two weeks after the accident enquirers were told she was no longer a patient. Calls to her home by the Olcotts and others brought no response. The phone was never answered. A personal call at the house by the Olcotts found the doorbell also unanswered. “There were no lights, and the house looked as if it was no longer occupied,” said Grant.

“A few weeks later a ‘For Sale’ sign went up on the house and, we later discovered, the house and all the contents that they had gathered so lovingly over the years, were sold to a George Smith of Washington, D.C. Neighbors told us the furniture was moved out during the night and for a long while the house remained empty. We tried to locate Mr. Smith but ran into a dead end wherever we tried.

“We were not the only ones concerned. Florence and her mother had many friends who were puzzled about their seeming disappearance, but for some reason that seems incredible today, no one was seriously concerned enough to do anything about it.

“Two weeks later Sid and I left for California where he was to work with Famous Players,” said Grant. “We made one final check at the studio for information about Florence but Ed Thanhouser told us not to worry, although he wasn’t sure where she was travelling, we would no doubt hear from her in due course. We left our new address in Los Angeles with Ed and several other people, asking that it be given to Florence when they heard from her.”

Less than a month after reaching California, the Olcotts were shocked to read in the West Coast movie trade papers that La Badie had died on October 13 in the Ossining Hospital “from the after-effects of a car accident two months earlier” (the “accident” had in fact happened in April, six months earlier). Funeral arrangements were announced for October 28 from the Campbell Funeral Home, 66th Street, in New York.

“We immediately telegraphed a floral wreath and telephoned the Campbell Funeral Home asking that Mrs. La Badie please call us as soon as possible. We requested that she be told that we would welcome her in our home once she felt able to travel, but we never had an answer.

“Newspaper friends in New York told us later that the funeral was a quiet one, with only a few studio heads present, and with none of her contemporaries like Pickford or Lawrence attending. ‘Florence’s mother was not there,’ said one reporter who had known La Badie well. ‘When I asked the funeral director where I could reach her, I was rather rudely told it was of no concern to me or my paper!’”

Valentine Grant’s memories of Florence La Badie ended at this point. “The story doesn’t have any ending, I know,” she said. “To add anything more would be to speculate on things about which we have no real knowledge.”

Sidney Olcott also seemed reluctant to delve any deeper into the strange happenings of 1917. “It all happened twenty-six years ago,” he said. “Perhaps it might be better to leave it as one mystery without an ending.”

Mary Pickford, when asked about the mystery a few days later, said: “I think Sid and Val should not discuss those happenings of so long ago. There are things I could tell you, but you would say they were impossible to believe, so if you will allow me I would like to change the subject. These things happened so many years ago and there is no point now in trying to find out the truth. There are some things that are better left unresolved.”

Asked if she remembered Governor, then President, Woodrow Wilson visiting the studio, she became quite agitated and said: “I don’t wish to talk about or remember that man.” She walked out of the room without another word.

James Baird, a junior reporter for the New York Telegraph, aged seventeen at the time of La Badie’s death and still living at the age of ninety-three in 1993, claimed that he had discovered shortly after the “accident” that the brake line on La Badie’s car had been cut through with a knife.

“I reported it to my editor and he seemed quite excited when he read the story. But next morning, when I asked why it wasn’t printed, he told me the story had been killed and that I was to do no more digging about the car or Florence La Badie’s accident.

“The police handling the case knew the brake had been deliberately damaged because they admitted that to me after I had talked to the mechanic who checked the car in the garage where it was towed.

“Despite what my editor told me, I went back to the garage a few days later and discovered the car had vanished. The garage owner said ‘officials’ had taken the car. The mechanic who had told me about the brake damage had gone, too. ‘He got a better job,’ said the owner. Asked where, he said, ‘I have no idea.’ I reported these latest facts to my editor, but again he told me, angrily, to let the matter drop. Twenty-four hours later I was fired. Somebody up there with considerable power obviously told the paper to print nothing.

“Two days later, when I went back to the police office in Ossining to ask for their help in writing my story, which I felt I could sell somewhere, I discovered someone had blacklisted me. No one would talk to me. I was no longer welcome at the police office.

“With the war still on, good reporters were at a premium, and I figured I’d have no trouble getting a new job. But once I sent my name in to the editors I got no further than the front door. Finally, to get work I had to go to a small paper in upstate New York. Even up there I was contacted by two tough looking men who pinned me to the wall one night outside the house where I was staying. ‘Not got any more ideas about La Badie’s car, have you,’ said one. I told him that incident was closed as far as I was concerned. ‘Good,’ said the other man. ‘You’ll find it healthier to keep thinking that way.’ They then walked away.

“Quite by accident I met the maid who had been employed at the La Badie home on Claremont Avenue when Florence retired for the first time in March 1915. It took some time to gain her confidence but one day she told me something I had suspected for a long time. Florence had a baby in September [1915].

“I spent every spare moment I had over the next ten years searching the registers of births in New York and New Jersey and Washington, D.C. The baby was not registered in New York but in Washington, and the father was listed as George Smith. His address in the files was that of an office block that no longer existed. I have tried for many years but have failed to discover what happened to George Woodrow Smith, for that was the name the baby was registered under. I advertised for him in daily and weekly newspapers across the country. Spent all my money doing that but got no replies.

“And that is the end of my story,” he said. “I think it is obvious who needed to shut Florence’s mouth. But I can’t prove it. I don’t think it ever will be proved after all these years.”

Florence La Badie is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in New York. The grave is well tended by the cemetery, and the grave marker can still be clearly read. Occasionally some red roses are placed on the grave. But no one can say where they come from. Perhaps James Baird? Or perhaps George Woodrow Smith, if he was ever told the truth about his parents!

Of Mrs. Helene La Badie’s fate there appears to be no record. New York city and state files, which go back well beyond the year 1917, have no listing of her death. So, presumably, whatever happened to her must have occurred beyond the state line. The plot in Greenwood Cemetery was purchased jointly for Florence La Badie and her mother. Why her mother never joined her there is anyone’s guess.

And who was the unknown man who leaped to safety from La Badie’s car just before it crashed? That is one more mystery in the life of Florence La Badie that will likely now never be solved. Even James Baird was unable to suggest an answer to that riddle!

One more unanswered puzzle is why Florence La Badie, well enough to be discharged from the Ossining hospital before the end of April, contacted none of her friends after that date. James Baird added a final enigma. “Why would it take six months, until October, for her to die ‘from the after-effects of an April accident’ from which she had officially fully recovered?” he asked. “And how did she die? The death certificate said natural causes. At twenty-four?”