“I doubt if the motion picture industry will ever again see the likes of Sidney Olcott. He gave our industry a dimension and respectability that only he, in those early days, could envision. His role in the acceptance of motion pictures as a legitimate art form must never be forgotten. Sid Olcott must never be forgotten.”

(Will Rogers, 1928)

Eulogies of such magnitude are usually heard as final tributes at funerals and memorial services. But, on February 11, 1928, when Will Rogers and more than 200 other celebrities from the era of silent films gathered at a testimonial dinner, Sidney Olcott had never been in better health. He sat in the place of honour at the head table in the crowded ballroom of Hollywood’s Roosevelt Hotel, listening with obvious pleasure to the praise bestowed lavishly on his achievements.

Four months earlier, Olcott, at the age of fifty-five, had announced his immediate retirement. With the first sound films in production, Olcott, one of the most imaginative and innovative directors of the silent era, had been hailed as one of the few capable of making the transition. His unexplained retirement had stunned the industry.

Will Rogers was not alone in his praise. Star after star who owed their fame to Olcott’s skilled direction rose to add their tributes. Norma Shearer, Richard Barthelmess, Pola Negri, and Warner Baxter pleaded with Olcott to continue to direct their films.

Marion Davies, the beautiful actress-protege of multi-millionaire William Randolph Hearst, said, “I have made only one film of which I am truly proud. That film was Little Old New York, which Sid Olcott directed.”

Hearst, who had not even rated a head-table seat, rose from his place in the ballroom. “I have no words in which to express, adequately, my admiration for the artistry of Sid Olcott. If he changes his mind, these words of mine can be used as a binding contract. I will personally finance all the talking pictures he wishes to direct over the next ten years.”

Telegrams lauding Olcott came from the great director, D.W. Griffith, Olcott’s major rival, and such giants as English actor George Arliss. Their pleas were in vain. Olcott did not change his mind. Never again did he set foot in a film studio.

Twenty-one years later, when he died at the age of seventy-six, he was a forgotten man. Will Rogers had been dead for fourteen years. Many of his friends from the silent era who had failed to make the transition to sound were also dead or living in quiet retirement many miles from Hollywood. Those who had found a place on the sound stages had rolled back their ages and were trying hard to make people forget that they had been part of the early days of the industry. Sid Olcott was long erased from their memories.

Olcott was born on September 20, 1873, only three months after his parents had arrived in Toronto, Ontario, from their native Ireland. Christened John Sidney Alcott, he did not adopt the name “Olcott” until he was, at fourteen, a seasoned actor with credits in more than thirty plays.

His childhood was happy. Although the row house in which the Alcotts lived was far from luxurious, the family was never short of food and good clothing. Sidney’s father worked on a road repair gang. His mother augmented this income by using her considerable talents as a seamstress for a theatrical costume maker and repairer. Sidney himself contributed to the family income by delivering newspapers to nearby homes when he was only five.

When he started school at the age of six, Olcott continued selling papers before starting classes. In the evening he earned small tips by delivering costumes from his mother’s employer to nearby theatres.

His main friends came from a boy’s orphanage that stood across the road from the Alcott family home.

His enthusiasm for the theatre grew. “It had an aura of excitement that thrilled me,” he told the New York Times in 1927. “The day I received a twenty-five cent tip I decided my future lay in the world of entertainment. Anyone who could give a twenty-five cent tip had to be very rich and since I wanted to be very rich what better profession could I find.”

From that day on, Olcott hung around the city’s many live theatres every night. Friendly performers allowed him to stand backstage to get a close-up of the costumes he had delivered.

At nine he won his first role in a play. “They were rehearsing one Monday when I dropped by the theatre,” he told the Times. “I was already skipping school two or three days a week because I was convinced the only education I would ever need would come from the theatre. The director spotted me and asked if I would be interested in playing a small part.”

The director walked Olcott home, convinced his parents that the $1.50 salary he would earn each week the play ran would be useful to him in the years ahead, and four days later he made his stage debut.

Olcott’s one line didn’t make him a star, but it made him more stage-struck than ever. Despite his excitement he did not forget his friends at the orphanage. “The theatre manager let a few of the boys in every night to fill the empty seats,” he told the Times.

In the next year he obtained six more roles. “Some were quite substantial,” he recalled, “but I seemed able to remember lines instantly, however complicated, so I was very popular.” At eleven, he was advising set painters how to make their scenery more realistic. “It may sound incredible,” he said, “but they listened and did what I suggested.” At twelve he was named in the program as assistant set designer!

By the age of fourteen he had appeared in thirty plays. He had also managed to graduate top of his class at school despite missing many classes.

Since Alcott was pronounced “Olcott” he officially adopted the name. “More often than not the program printers spelled it Olcott. Besides, there was a famous actor of that time called Chauncey Olcott. I hoped someone might think we were related,” he recalled years later.

His first newspaper review came from a play critic in Peterborough, Ontario. It read: “The young boy, Sidney Olcott, as William, adds warmth and what little believability there is in a play so unbelievable. Young Olcott will go far. This play will not!” After his death, a yellowed and tattered copy of the review was found in his wallet.

In 1898, when he was, at twenty-five, a veteran of regional theatre in Canada, he decided his future lay not in Canada but on Broadway in New York City. Actors on the way down the ladder when they appeared in Canada with touring companies started him dreaming with their tales of life in the “big city.”

The luck of the Irish was with him from the moment he stepped off the train in New York. A sudden gust of wind swept the top hat from the head of a dignified gentleman walking a few yards in front of Olcott. Dropping his suitcases, he chased after the hat and returned it to its owner. “He thanked me, and seeing my suitcases, asked if I was in the city for the first time,” Olcott told the Motion Picture Herald in 1914. “When he learned I had just arrived from Toronto he handed me his calling card and suggested I visit his office if I found any difficulty getting a job. ‘You’ll find a small map on the back of the card showing where my office is located.’”

Half-an-hour later, sitting in a small room that a friendly police officer had pointed out as ‘clean and Godly,’ Olcott looked at the card for the first time. His jaw dropped when he read the name:

Mr. John Ince

Theatrical Producer and Manager

1620 Broadway, New York City

“I couldn’t believe my luck,” he told the film magazine. “In New York only thirty minutes and I had in my hand an introduction to one of the most reputable men in the theatre. Ince was one of the people actors in Canada told me to make an effort to meet.”

In less than an hour Olcott was sitting in the waiting room outside Ince’s office. A friendly receptionist heard his story and suggested he wait. Minutes later the inner door opened and Ince came out accompanied by a man Olcott recognized as one of Broadway’s most renowned actors. “Ince looked around and saw me,” recalled Olcott. “For a second he looked puzzled, then he smiled and invited me into his office.”

“Young man,” said Ince, “I like your style. We haven’t been off the train two hours and here you are. Right now I need a messenger to deliver scripts and contracts to theatres and managements. Are you interested?”

Deciding this was not the time to tell Ince he was, at twenty-five, a veteran actor, Olcott accepted. The job paid $2.50 a week. Olcott decided it was a great opportunity to introduce himself to everything Broadway had to offer.

His climb to the top started only two weeks later. Olcott was busy dusting the outer office when Ince arrived. “Sidney,” he said sternly, “I am very disappointed in you. Please come into my office.” He pointed to a chair. “Sit down,” he said. “I have spent the past two weeks trying to find a young actor capable of playing the second lead in a new play I am about to produce on Broadway. Now I find I have that young man right here in my own office. Why did you hide your acting experience from me?”

Olcott stuttered his apologies and explained that he didn’t think he had the experience to deserve consideration for a Broadway show.

“Well,” said Ince, now smiling, “I was talking to one of my friends in the lobby of this building when you rushed in, as usual, in a hurry. You didn’t see me, or my friend, or you would have recognized a well-known actor who starred last year in a Toronto play in which you had a small, but, my friend tells me, a very well-acted role.”

Within hours Olcott read for the part and a contract for the run of the play was signed. On cloud nine, he was not even fazed when he discovered the star of When Harvest Days Are Over was only eleven years old. Like Olcott, Joseph Santley was already a veteran of the theatre. He and Olcott became friends from the first day of rehearsals and Olcott acted as his mathematics and English teacher during the play’s two-year run on Broadway and in theatres across the United States. “I was give a salary boost of $2 a week for the tuition,” he told the Telegraph in 1917.

Olcott and Santley followed their first success with two more Broadway hit plays, Rags to Riches and Billy the Kid. Their friendship lasted until Olcott died. Santley, by then a renowned film director, was one of the mourners at the funeral.

Santley, who died in 1971, moved from stage to film acting in the silent era, then to directing both silent and sound films. He was one of the first major film directors to move into television, where he pioneered many of the early live TV dramas.

In a 1970 interview with a writer from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Santley said of Olcott: “I knew from the day we met in ‘Pop’ Ince’s office that we would be friends for life. He had a quiet air of confidence that I liked. I tried many times to talk him out of retirement and believe the medium of sound films would have been enhanced and enriched by his original and inspiring ideas.”

During breaks between plays, Olcott returned to Ince’s office where he ran errands and cleaned the floors. “Why not,” he told the Motion Picture Herald. “I owed my career to him.”

Olcott was soon to be even deeper in debt to Ince, though neither knew it at the time. Film production companies in and near New York were, by then, turning out hundreds of one-reel films that were fast growing in popularity. Few established actors would condescend to appear before the cameras. But John Ince believed that the new entertainment craze had a big future. One day he suggested that Olcott might investigate the work possibilities at the Biograph Studio, where the demand for competent actors was increasing.

“The industry already intrigued me,” Olcott told the Motion Picture World in 1921. “So when ‘Pop’ Ince gave his blessing I had no hesitation.”

Thanks to his lengthy list of stage credits, Olcott was hired immediately. As a member of the Biograph stock company he played several different characters each day. “I recall playing in as many as ten different films in one week,” he said. But Olcott still found time to investigate the studio lighting, the crude set building methods and, most nights, he said, “I stayed behind and swept the studio floor.”

Frank J. Marion, Biograph’s sales manager, soon noticed Olcott’s enthusiasm and creative talents. He, and Samuel Long, manager of the company’s laboratory, had been discussing the possibility of forming their own independent film company. Olcott’s arrival gave their idea impetus.

Long raised $600 from relatives. Marion, who had the use of a loft in a 21st Street warehouse, had $300 which he used to buy wood and other materials for set building. The two convinced George Kleine, owner of the largest film distribution centre in Chicago, to guarantee their bank account so they could purchase a camera, film, and lighting equipment.

Olcott, when offered a year’s contract at $20 a week, was easily convinced to become the first employee of the new company. So Kalem (a name created from the initials of Kleine, Long, and Marion) came into being.

Kalem’s first contract, with Olcott, was signed on a Friday in June 1907. The following Monday Olcott arrived at the 21st Street warehouse to find a carpenter, a lighting man borrowed from a New York theatre, and a cameraman with very little experience.

“Frank Marion handed me the studio keys and told me he expected the company’s first film by Friday, at the latest,” Olcott told the Motion Picture World fourteen years later. “That was the first time I realized I was expected to direct for the company. I gave the carpenter a rough sketch of what I wanted him to build, sent the camera operator out to borrow furniture from some of my friends, and told the lighting man to rig up the best he could from the few lights Kalem had been able to afford.”

Marion and Long set to work creating a primitive laboratory while Olcott headed for ‘Pop’ Ince’s office to recruit whatever competent actors were available.

Sketching out in his mind a possible story, Olcott found Joseph Santley, Santley’s brother Fred, and another actor, Robert Vignola, who had worked with Olcott in Billy the Kid, waiting to see Ince.

The trio never did see the producer that day. “Sid was so enthusiastic,” recalled Joseph Santley years later, “that we left the office, grabbed a streetcar, and headed for the Kalem studio. By the time we got there Sid had a story line for us. The set wasn’t quite ready so he sat down and scribbled out on pieces of paper what I now believe must have been the very first film script. He rehearsed us as though we were preparing a stage production and by the end of the day we had completed Kalem’s first film.”

Sleigh Bells was a big success. George Kleine offered it through his distribution house as an “exclusive masterpiece from a company that will revolutionize the motion picture industry.”

The film didn’t set the world on fire, but it did nothing to diminish the stature of its principal actors. It is historic in that it used spotlights for the first time to emphasize individuals and objects essential to the continuity of the film. And it introduced Sidney Olcott to the industry as a highly competent director.

While Olcott was acting in some of the scenes, he deputized Robert Vignola as his assistant. As a result, Vignola too became a permanent member of the Kalem company. Within weeks, guided by Olcott, he was directing in his own right. Vignola went on to become one of the silent era’s finest directors. He moved into the sound era with considerable success, and when he retired in 1937 he owned a large home in Beverly Hills and a solid bank balance.

Olcott stayed with Kalem for seven years. The company prospered under his guidance. His hand-written paper on the use of backlighting for special effects, prepared in 1909, was mentioned by Alfred Hitchcock in a 1942 interview with the Los Angeles Examiner. “It is quite remarkable,” said Hitchcock. “What he suggested thirty-three years ago I still use today to create some of my most effective scenes. What a genius he must have been.”

One of the first rules laid down at Kalem by Olcott was a firm directive that no film be started until a complete “written synopsis” was prepared by the director and approved by himself. Many of the “scripts” he wrote himself. Others came from writers he trained in the new medium.

Kalem records show that weekly profits averaged $5,000 only three months after the company’s formation. The money was used wisely. Kalem purchased a four-storey building in Fort Lee, New Jersey, and converted it into a well-equipped studio complete with the most modern laboratory in the industry. Olcott said in 1943 that the New Jersey location was chosen because “it had many beautiful outdoor and waterside settings within walking distance,” a far cry from today’s decaying industrial areas near the location of the old studios.

Olcott recruited his actors in many different ways. One of his favorites was to find an actor with a wardrobe suitable for the film being planned. In need of an actor for a “society” film, Olcott encountered actor George Melford strolling down Broadway immaculately dressed in a “morning suit.” “You’re in,” said Olcott. “In where?” asked Melford. “My next picture,” said Olcott. After sitting down to a five cent drink, which Olcott entered in his weekly expense account, Melford joined the Kalem stock company. Like Vignola, Melford soon became a camera assistant and within weeks was a director in his own right.

Records show that Melford directed more than 200 films in a career that lasted until 1937, when he again became an actor in many major films including A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, The Robe, The Ten Commandments, and The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek. In a 1953 interview, while filming The Robe, he told a Picturegoer reporter: “My entire career is due to Sid Olcott. He is dead now, and few people remember him. But he had a strange ability to make many people, like me, get the most out of everything we did. While people like me are still alive Sid Olcott’s genius is still alive.” Picturegoer printed a terse explanatory note: “Sidney Olcott was a silent picture director who is often recalled more for the performances he got from his actors than for his directing abilities. He died in 1949.”

Actress Gene Gauntier made so many intelligent story suggestions to Olcott that he hired her to write on a full-time basis, the first writer to be hired by a film company exclusively to write scripts. Two other actors converted to directors by Olcott, Kenean Buel and James Vincent, became recognized as two of the industry’s best. Gauntier told an historical writer from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1949 that “Olcott’s greatest asset was his willingness to let people try things they had never done before. And he was never concerned that those he promoted might equal him in ability. He knew he was a genius but never flaunted it. If he created other geniuses he was delighted.”

In the early days of the industry, directors stole many of their stories from books and magazines, rarely — if ever — crediting the original writer. Certainly, none received fees for their work. All that changed when Olcott used not only the story but also the title of Lew Wallace’s Ben Hur for a one-reel epic. The estate of Wallace sued, and in the first court case of its kind, Kalem had to pay $25,000 to the late writer’s family.

Olcott’s film of Ben Hur was rather undistinguished, but because of the legal publicity it did record business and more than recouped the $25,000 court judgement. The film is still maintained in archives in the United States. From that day, most companies made sure they paid authors for their stories.

Olcott’s self-proclaimed policy, “If in doubt, do it,” got him into difficulties throughout his career. The Scarlet Letter, which he scripted and directed, was the first film to be banned by the National Board of Censors, the industry’s watchdog of the time. To get the one-reeler on the nation’s screens, Olcott had to shoot a new ending so that the “wronged” Hester married the minister who had “wronged” her. He wrote his own publicity material for The Scarlet Letter. “Is this the banned version, or the revised version? See for yourself.” Needless to say, it was the revised version, but it drew many thousands of bonus paying customers.

Just before his retirement in 1928, Olcott told the Motion Picture Herald that on many later occasions he deliberately made films with scenes or endings that he knew would be unacceptable to the Board of Censors. “I filmed, at the same time, the alternate scenes I knew they would demand,” he said. “When they banned the film I had to make simple changes. The banning drew crowds to the theatres and Kalem’s profits continued to rise.”

In 1908, when Olcott was thirty-five, he convinced the three Kalem owners to move out of New Jersey for the winter months. “The primitive cameras of the time froze easily in cold weather and outdoor shooting became impossible,” he told the New York Times in 1927. “Since we had discovered that audiences loved outdoor scenery I suggested a move to Florida for five months, where the scenery was not only different but available all winter long.”

A Jacksonville theatre owner, A. S. Hoyt, agreed to pay the cost of the unit’s move to Florida if Kalem would guarantee that he would get first showing rights for his theatre. Olcott and Hoyt decided to make each opening a gala occasion with the actors and director attending. The studio loaned its lighting equipment to floodlight the theatre front and thousands of people gathered to see the “stars.” The ten films made in Florida are on record as being the first “official opening nights” of the growing film industry.

Olcott’s company took over a boarding house named Roseland in Fairfield, on the outskirts of Jacksonville. The rooms used as bedrooms at night were converted to indoor sets during daylight hours when the weather outside was too rainy for location work.

Hoyt told Olcott at the end of the season that he had made a small fortune from the Kalem films. During the next summer he built three new theatres and founded the Hoyt chain, which at one time owned more than eighty movie palaces.

Kalem used hundreds of local people in the Florida films. Rarely did Olcott need to pay for their services, and the huge nightly audiences at the Hoyt theatre were often these same “extras” with their families. They cheered every time they recognized a scene or person on screen.

The Florida venture almost came to an end after the showing of the first film. A Florida Feud told the story of murder and revenge among the sharecroppers (tenant farmers who paid a portion of their crops as rent) of the area. Olcott must have come a little too close to the truth, and the sharecroppers didn’t like the way they were portrayed on screen.

Shortly after midnight on the night of the film’s premiere, a group of hooded men raided the boarding house and dragged Olcott into the street. Next day’s newspapers reported him as “badly beaten and left in a pool of blood.” Rushed to hospital in Jacksonville, he was diagnosed with broken ribs and many cuts and bruises. The New York Telegraph ran the story on its front page, reporting that “only intervention by Kalem actors and technicians saved Olcott’s life.”

Olcott loved the publicity. He ordered the Fort Lee laboratory to issue the film nation-wide together with a lurid account of his beating. Kalem records show that the company made enough money from this one film to cover all the Florida winter expenses. The nine additional films were a bonus.

Was the sharecroppers’ attack a hoax designed to create large audiences for the film? Olcott, many years later, admitted that he perhaps exaggerated his injuries a little. Kalem files show that he was back on the set, ready to direct, only twenty-four hours after the beating, suggesting that he may have exaggerated a lot!

Olcott and the other Kalem directors were still the only ones using a “scene and story” sequence, as the early scripts were known. Most directors not influenced by Olcott had only a rough idea of what they planned to film, improvising as thoughts occurred to them during the shooting. The few films made by Olcott that remain in archives contrast sharply with their intelligent continuity when compared to those of most other directors whose material had no pre-set pattern.

Success in Florida gave Olcott more ambitious ideas. Kalem quickly agreed to his suggestion that some of the winter profits be used to send a few actors and small crew to Ireland.

With many of the stories of “old Ireland” his father had told him as a boy deeply etched in his mind, Olcott, Gene Gauntier, Robert Vignola, and cameraman George Hollister sailed from New York to Queenston, Ireland. Hollister, one of the best cameramen in the industry, told the New York Telegraph that “the opportunity to work with Olcott would have taken me to the ends of the earth.”

Ireland was all Olcott had hoped for. “I fell in love the moment the ship docked,” he told the Telegraph on his return to New York. “I had the scene and story sequences written for several films and we were ready to shoot.” The company found a local boy with a natural flair for acting and two hours after they set foot on land they were filming The Lad from Old Ireland.

Gene Gauntier took over the writing. Vignola directed two of the films. The entire group, including Olcott, played parts in the films. Vignola recalled years later that he played four different parts in one of the films.

The unit completed five films in two weeks. Olcott then cabled Kalem for more money so the company could travel on to Germany. Records show that Frank Marion wired him an additional $300. It was enough to permit three more films to be made in Germany before the unit headed for home.

Only absent from the United States for a little over eight weeks, the unit arrived home to a blaze of publicity. As head of the first film unit to travel overseas for location shooting, Olcott found himself in demand as a speaker. “The Irish clubs all wanted to hear me,” he recalled. “I addressed eleven groups ranging in number from 50 to 1,000 in less than two weeks. As a result, all the films made in Ireland were profitable. It seemed everyone with Irish ancestry wanted to see the old country again.” The German films didn’t do too well, but Kalem still showed a handsome profit from the trip.

Profits were so good that Frank Marion urged Olcott to make another trans-Atlantic crossing in 1910. Remarkably, the success of the location shooting didn’t inspire other companies to follow suit and Kalem’s stock rose as their real scenery was compared to the cardboard sets and New York scenes which were getting to be a bore with moviegoers.

Gauntier, Vignola, and Hollister eagerly accepted Olcott’s offer of employment on the second European trip. He added actress Alice Hollister, wife of the cameraman, three more actors, Jack J. Clark, Jack P. McGowan, and Helen Lindroth, plus a scenic artist, Allen Farnham.

Olcott wasn’t a man to waste money. On the first day out at sea on the SS Adriatic, he called his group together and presented them with two scripts he planned to shoot on board. When the captain announced the unit’s plans there was a long line of people waiting to be chosen as unpaid extras. “The captain insisted on first-class passengers being given priority,” recalled Olcott.

Making his first film on board the Adriatic nearly cost Olcott his life. (Or was this another of his successful publicity stunts?) The script called for an actor to climb down a rope on the outside of the ship’s hull. No one volunteered, so Olcott once more became an actor. Unfortunately for Olcott, a porthole opened just above the spot where he was clinging to the rope and a cook dumped a can of garbage on his head. His hands slipped and he only regained control two feet before the end of the rope. He climbed, as the script demanded, into an open porthole two decks down. The camera filmed the action and it is still available to be seen in film archives in Washington.

Since the scene inside the cabin had already been shot, it had to be re-done so that Olcott would have the garbage on his face as he climbed into the room to face the jewel robber. “I had to decide which of the two evils was the lesser,” he told the Motion Picture Herald. “Whether I would go down the rope again or have a pail of garbage thrown over me. I decided the garbage was preferable.”

The completed film is today viewed as a comedy. When filmed it was intended as a drama. And, if Olcott is to be believed, it was almost the end of his career.

In Ireland, a film written by Gene Gauntier about Rory O’More, an eighteenth century revolutionary hero, upset the British authorities. With threats of expulsion from Ireland hanging over their heads, Olcott put the unit back in favour by producing two high-quality three-reelers, The Colleen Bawn and Arrah-na-Pogue. The two films were adapted by Gauntier from plays by the Irish-American dramatist Dion Boucicault. A poem by Thomas Moore provided the story line for You Remember Ellen. In eight weeks the unit made seven films, most of them two- or three-reelers.

Olcott made sure he paid for the screen rights and his meticulous accounting for every penny showed receipts from the authors or their agents. Thomas Moore received three pounds ($12) for the rights to his poem.

“I always accounted for every penny I spent,” said Olcott in 1942 to the Motion Picture Herald. The extent of his accountability is reflected in a couple of lines repeated on several occasions during the trip:

“Three shillings for service of extra girl after hours for

personal pleasure.”

“One shilling for Irish Whiskey to encourage extra girl to

become friendly.”

With huge profits coming in from virtually every film Olcott made, Kalem was not inclined to argue about this extra-curricular activity.

Even when Olcott and Kalem announced a third trip to Europe, in 1911, no competitors followed in the unit’s footsteps. Kalem films were eagerly awaited and the company moved to the top of the production ladder.

Because of adverse British reaction to the New York success of the film glorifying Rory O’More, Olcott — at Marion’s urging — decided to bypass England and Ireland. The 1911 unit, now eleven strong, including most of those who had made the two earlier pioneering trips, landed in France. They made five films there before heading to Spain and Morocco.

In Morocco, Olcott convinced two enemy Bedouin tribes to “hold a battle” for the camera. All went well until cameraman George Hollister got a bullet in his arm and had to be taken to hospital.

“This was the first time I realized they were using real bullets,” Olcott told an interviewer from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences in 1929. “I tried to stop the battle but the Moroccans were just getting in the spirit of things and wouldn’t listen. So I shrugged my shoulders, took over the camera, and shot some scenes which I am sure, if shown today, would be quite horrifying.”

Next day the battle ended and the two chiefs arrived arm in arm for their pay. “I gave them twice what I had promised and was never more happy to see anyone go away,” he said.

Shooting additional scenes with less warlike locals, Olcott came up with enough ideas to make four different films in just over two weeks.

With his Irish-Catholic background, Olcott had long been fascinated with the idea of making a movie based on the life of Christ. He sent his unit to the Holy Land while he headed for London in search of an actor to play Christ. The announcement that he planned a five-reel epic called From the Manger to the Cross drew storms of protest from church organizations and those who remembered Rory O’More as a rather unsavory character.

Olcott sensed he had a box-office winner. In a New York Times article in 1913, he said, “I knew then I had to make the film. With all that free publicity the film would obviously be a big profit-maker.”

In London he was shocked to find that actors and their agents were not interested in the role of Christ. Swayed by the bad press the idea was getting, actors feared association with Olcott would destroy their careers. On the verge of giving up, Olcott was approached by Thomas Blackmore, principal of Blackmore’s Theatrical Agency. He said he had the perfect actor for Christ, and the actor was willing to take the role. When Olcott met Robert Henderson Bland, a gifted Shakespearean actor who had already achieved some fame on the London stage, he agreed. Bland walked into Olcott’s hotel room wearing a long golden wig, dressed in a white flowing robe. “I am Jesus Christ,” said Bland. “I will portray myself in your film.”

Bland told them he had received a vision during the night and that God had told him he was His chosen son. “Frankly, we thought he was mad,” said Olcott. “But we didn’t argue, he was obviously what we wanted.” Two days later Olcott and Bland sailed for Egypt where they found all pre-shooting preparations were complete.

Gauntier and the unit had built an outdoor stage that was large enough to hold sets for all the interior scenes. They had also obtained permission to shoot on the Sea of Galilee and along the procession route to Calvary. Local authorities, in exchange for generous handouts, guaranteed the company would have no troubles and as many extras as they needed, at no charge.

From the Manger to the Cross was the first five-reel film to be shot. Back in Fort Lee, Marion and Long rubbed their hands nervously as Olcott took five weeks to complete the film. The bills mounted as production time lengthened, but Kalem decided Olcott knew what he was doing and they offered no interference.

By the time for shooting came, Bland had grown his own golden hair to shoulder length and the wig was discarded. Olcott reported to Kalem that Bland was acting as though possessed. On his return to New York, Olcott told reporters that for the first time in his career he had allowed an actor to be in total command of every scene. “Bland needed no direction, he was superb,” said Olcott.

Bland told Olcott that he was totally unaware of the camera and what he did came naturally “through some strange and compelling force.”

Olcott, who played fourteen roles as well as directing the film, was a nervous wreck when the shooting ended. Gauntier took the negatives directly to New York while Olcott and the rest of the unit sailed to London where they had heard that Dean Inge, the “gloomy dean” of St. Paul’s Cathedral, had issued a statement praising Olcott for his determination to show the “true story of Christianity.” Olcott was received by the dean, an audience that prompted hundreds of letters for and against the movie in London newspapers.

A revived Olcott took his crew to Ireland, where they made four films in one week before sailing to the United States. Their return to New York was greeted with considerable press coverage and letters for and against the film filled the newspapers. Olcott admitted to a Films in Review writer some twenty years later that everyone from Kalem sent at least two letters to the papers. Some were designated to write in support, others asked that the film be banned. “Of the hundreds of letters the papers printed, we sent perhaps forty,” he recalled, “but I must admit we set the ball rolling.”

Robert Henderson Bland was brought by Kalem to New York for the special opening of the film in October 1912. Olcott had taken several months editing the hundreds of reels the unit had filmed.

Although Bland was not paid to travel first class, the captain of the liner, awestruck at the sight of the blonde giant strolling around in the robes he had used in the film, moved him into the best suite on board.

Bland was a sensation in New York. He refused to use any vehicle for his travels, walking everywhere. Crowds followed him every day and hundreds more waited outside his hotel for his daily appearance. Many knelt down or bowed when he left the hotel.

From the Manager to the Cross was screened publicly for the first time at John Wanamaker’s Auditorium in New York City on October 14, 1912. An orchestra of forty musicians played a specially written overture and accompanied the picture with an impressive score. Everyone of importance in the religious life of New York was invited. Most attended, as did civic leaders and important people in the film industry.

Reviews in the New York papers called the film “entrancing,” “spellbinding,” “inspiring,” and “the most wonderful use of the new medium of film.” Most of the earlier criticism was now over, and the few letters denouncing Olcott and Kalem for daring to put the story on film as entertainment were drowned out by the hundreds in favour.

Olcott was triumphant. The industry he loved acclaimed him as its greatest director. Bland, too, was basking in the film’s success. He stayed in New York for almost three months with Kalem willingly footing the bill. He received invitations to the homes of the city’s elite. The widow of John Jacob Astor IV (lost on the Titanic) threw a special alcohol-free reception for Bland, during which she asked him to “bless” her son, born after her rescue from the Titanic!

Offers came in to Bland’s hotel for him to appear on the New York stage and in other films. He turned every request down. At the urging of Olcott he made one personal appearance at the small theatre owned by Louis B. Mayer in Haverhill, Massachusetts. Just before he was scheduled to sail back to England, this time first-class, Frank Marion offered him a large cheque to say thanks for the publicity he had given the film. Olcott, who took the cheque to his hotel, talked for many years about an unusual happening when he met with Bland.

“I offered him the cheque, but he waved it away,” said Olcott. “He then grabbed the cheque and pressed it to my forehead and then his own. “There are others who need it more than I,” he said. He paused, then added: “There is a boys’ home in Toronto, Ontario, to which this money must be sent.”

Olcott emphatically denied suggesting the orphanage to Bland. “Why he said that I will only know after my death,” he said.

But the money did go to the orphanage that still stood across the street from Olcott’s first Canadian home. The New York Telegraph obtained a copy of an entry in the orphanage records that read: “Received from the Kalem Film Company, of New Jersey, U.S.A., at the express request of Jesus Christ, the sum of seven hundred and fifty dollars.”

Bland returned to England, but from that time on would only act in religious plays. He made only one other film, General Post, in 1920.

During World War One Bland became an officer in the British Army, winning medals for his apparent disregard for his own safety. He is said to have saved many lives with his heroism. After the war he wrote a book entitled From the Manger to the Cross, in which he declared that Christ had entered his soul during the filming and he was unaware of what he had achieved until he saw the film in New York. He said Christ stayed with him during World War One and made him invincible.

Asked years later what he thought of Bland and his book, Olcott would only say: “I believe he was one of the greatest actors of all time, but that he was an actor, nothing more.”

Kalem made millions of dollars profit from From the Manger to the Cross. It is still shown today to film societies and scholars studying early film making techniques. Even when compared with today’s advanced technology, it contains striking and beautifully composed scenes that have rarely been equaled. When sound arrived in the industry in 1928, historians searched for the original orchestral score in vain. They had hoped to record the music to play with the film. “Despite its silence, it is still a very moving picture,” said renowned director William Wyler in 1988.

Despite the obvious advantages of having a director of Olcott’s stature on the Kalem payroll, Marion, Long, and Kleine declined to increase his salary beyond $150 a week. Angry with their attitude, he resigned and joined forces with Gene Gauntier to produce films independently. Planning to shoot all year, they set up business in Jacksonville, Florida.

In 1914, after completing a series of successful and profitable films, Olcott and Gauntier once again set sail for Ireland. Most of his old unit went with him, leaving New York on June 11. Scripts were already prepared before the unit left and Olcott rehearsed his actors on board ship.

Although the trip had to be cut short when World War One erupted, it was a journey that had an immense effect on Olcott’s life. Before the boat reached Ireland, Olcott had fallen in love with actress Valentine Grant, who had been added to the unit at the last moment. In September they were married in a quiet ceremony in New York. It was a marriage that lasted, in harmony, until her death in 1948.

A number of articles over the years suggest that Olcott achieved “miracles with actors and actresses considered just average” by hypnotism. Actress Alice Hollister and her cameraman husband George, who worked with Olcott on many occasions, were convinced that hypnotism was the secret of his success. “He could calm the most erratic actor in seconds, simply by looking him directly in the eyes,” said Mrs. Hollister. “We believe he used hypnotism. Just look at those piercing blue eyes and you’ll see what I mean.”

Other reports suggested he used hypnotism to obtain financial backing for his independent productions, but his inability to convince the extra girl in Ireland to be friendly without the use of whiskey, and his failure to convince Kalem to increase his $150 salary, suggest that hypnotism was a fancy of the Hollisters’ imaginations.

But there can be no doubt that Olcott did have some form of thought transference powers that enabled him to tell actors what to do without speaking a word. Mary Pickford told actor Sam De Grasse that it was this method that made her bow to his suggestions during the making of Madame Butterfly. “He spoke very little,” she said, “but I was never in doubt of his intentions. This is perhaps why I disliked him. I felt he controlled my mind.” (Could this be the method by which Robert Henderson Bland knew about the boys’ home in Toronto?)

Valentine Grant told the New York Telegraph that she said “yes” to Olcott’s proposal of marriage before he spoke a word. “I knew he was going to ask me and I blurted out the ‘yes’. Come to think of it, I don’t believe he ever did ask me.”

Mrs. Olcott told the Telegraph writer that on many occasions, while he was away on location shooting, she heard him telling her of happenings on the set. A day or two later, she said, a letter would arrive saying exactly the same words.

The Telegraph decided to test her statements. In 1916, Olcott, while in Boston, was told to write a series of words, given to him by the mayor of Boston, on a piece of paper. The words were revealed to no one else in the room. In New York, seconds later, Mrs. Olcott wrote down the same words on a piece of blank paper she was given. An open telephone line between the two cities confirmed that the words she wrote were the words given Olcott in Boston.

The experiment continued with words, numbers, and names for more than thirty minutes. Valentine Olcott was able to achieve ninety percent correct answers. When the experiment was tried in reverse, with Mrs. Olcott trying to send messages to her husband, the tests were a total failure.

Olcott had a sixth sense for impending disaster. He once called a friend, hundreds of miles away, urging that the friend take his wife and family away for the weekend. He said he sensed danger in their home. The friend did send his family to visit his mother, but he stayed home. Twenty-four hours later he was burned to death in a fire that was never satisfactorily explained.

Numerous other things are documented. Once, while on location in Florida, he halted shooting and moved his crew and actors to the shelter of a nearby barn. Only ten minutes later an unexpected twister swept through the area, killing several people and causing widespread damage. The twister swept through the location site but veered ninety degrees just before it reached the barn and the unit remained safe as the wooden structure was untouched.

The Olcott-Gauntier partnership lasted less than two years. The split was amicable. Gauntier was offered a lucrative writing contract with Universal films in Hollywood, and in the summer of 1916 she boarded a train west with Olcott’s blessing.

Olcott perhaps sensed that his own future also lay in California. Six months after Gauntier’s departure he and Valentine Grant were on a train heading for Los Angeles. Famous Players had offered him $1,000 a week to do nothing else but direct. Directing, he now knew, was to be his forte in life.

Before he left Florida, Olcott and his wife founded the Motion Picture Actors’ Welfare League for Prisoners. Olcott and other production companies took their films to jails, often giving the prisoners a look at films not yet released. The stars and director accompanied each film, encouraging prisoners to think positively about their eventual release. Olcott himself donated a dozen projectors to the jails and other producers proved to be equally generous.

Olcott encouraged newly released prisoners to visit him in Hollywood. Often he was able to find them work in the studios. A few years before his death, he told the Los Angeles Times that one of the industry’s top actors and a well-respected director were former prisoners who had “gone straight” on release. “I helped train them,” he said. “Neither has given me cause to regret my actions.”

The Welfare League remained in existence for more than fifteen years until prison entertainment became an official part of the rehabilitation system throughout jails in the United States.

Olcott received a hero’s welcome to Hollywood. “I was offered my choice of scripts, my choice of stars, and the right to amend the scripts any way I wished,” he told the Los Angeles Examiner in 1926.

His first choice was to direct another Canadian, Mary Pickford, then at the height of her popularity. The two feuded from day one on the set of Madame Butterfly. Pickford told the Los Angeles Times that Olcott “even tried to tell me, Mary Pickford, how to act. Even made me, no forced me, to do close-ups that I had never done before and didn’t like.”

Despite Mary Pickford’s displeasure, Madame Butterfly, a five-reeler, was a great success. The close-ups Olcott demanded showed a remarkable range of expression that Pickford had never been able to achieve before. One year later she requested Olcott to direct her in Poor Little Peppina. Again they feuded, but once more they produced a very successful film, both financially and artistically.

It is interesting to note that when Pickford made a financial settlement with Famous Players that gave her the right to total ownership of ten of her films, she selected Madame Butterfly and Poor Little Peppina as numbers one and two. Years later she told an interviewer from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences research department that despite their “artistic differences” she acknowledged Olcott to be one of the greatest directors of the silent era.

Stars like Will Rogers demanded Olcott as director of their films. The 1918 film, The Innocent Lie, which teamed Rogers with Olcott’s wife, Valentine Grant, is looked on today as an example of film making that was technically and artistically years ahead of its time.

Seven Sisters, starring Marguerite Clark, Diplomacy, with Marie Doro, The Smugglers, with Donald Brian (the Broadway actor who was born in Newfoundland) and Scratch My Back, with T. Roy Barnes and Helene Chadwick, all enhanced Olcott’s reputation in Hollywood.

In 1921 he directed The Right Way, a prison story that starred Edwards Davis and Helen Lindroth. Although Olcott refused to identify the actor he brought from jail to stardom, there is evidence to believe it was Davis. The story, written by Olcott, told of a prisoner’s determination to make good. Davis went on to make fifty more films and a reputation as a “gentleman.” He remained successful into the sound era, making movies until a year before his death in 1936. The identity of the former convict who became a director was also never revealed and his name is still a mystery.

Olcott was on top of the world in 1922 when he suddenly refused all new assignments offered him. Fellow workers said he had become depressed and was drinking on the set. Without any explanation he left his wife and home in Beverly Hills and bought a coach-class ticket to New York City. There he vanished.

Friends were puzzled. He left all his financial affairs in order. There was plenty of money for his wife and no debt. If Valentine Olcott knew the reason for his absence she told no one.

A year passed, and neither his wife nor his friends heard a word from him. Attempts to trace him in New York failed. It was a mystery that might never have been solved had it not been for the determination of publisher William Randolph Hearst, then king of the fabulous Hearst Castle on the “enchanted hill” in San Simeon, California.

Hearst, in need of a capable director to revive the flagging career of his beautiful actress-mistress, Marion Davies, viewed hundreds of films seeking the right person. The Will Rogers film, The Innocent Lie, intrigued him. He asked to see more Olcott films. Four films later Hearst was convinced. “Sidney Olcott must direct the next Marion Davies film,” he said.

Frustrated because he was unable to locate Olcott, Hearst used the columns of his New York paper to find him. Within hours of the publication of a story offering a substantial reward to any person able to provide Olcott’s present address, a New York tenement resident called the editor to say Olcott was living in a $3-a-week room in a run-down building. He was, said the caller, constantly drinking cheap whiskey and eating very little. “He is quite ill, and needs help,” she said. When Hearst received the message he sent a telegram to the tenant asking that she tell Olcott to call him immediately.

When no call came, Hearst boarded a train from Los Angeles to New York. Met there by his driver, he was taken directly to Olcott’s seedy address. He said later he was shocked by what he found. “But we carried him down to the car and took him to my New York apartment where a doctor was waiting.”

Valentine Olcott was notified that she should join her husband as quickly as possible. Hearst provided one of his private rail coaches to bring her to New York. Nurses and doctors were at his bedside twenty-four hours a day, and within weeks he had gained twenty pounds and no longer demanded alcohol.

Three months later Olcott walked on the set of Little Old New York with Marion Davies on his arm. Hearst had gathered together dozens of the industry’s major stars and they, together with hundreds of extras and technicians who had worked with Olcott in the past, stood and applauded his arrival. Olcott is said to have “cried like a baby.” But an hour later he was directing Marion Davies in her first scene.

Little Old New York is the only one of the fifty films made by Marion Davies that was acclaimed by critics in papers not controlled by Hearst. Olcott’s direction was applauded. Davies, who had been coached for each scene by Olcott, received rave reviews for her performance. It is interesting to note that Little Old New York is the only one of the films in which Davies starred that is remembered by photographs and a large theatre poster in the Hearst Museum at San Simeon in California.

Olcott was back! He never explained his absence to anyone, unless privately to his wife. And he never again directed Marion Davies. “There is a simple explanation for that,” said Robert Vignola. “Sid was an honorable man. He found the advances by Marion Davies quite unacceptable. He could not betray his wife or Mr. Hearst so he declined to work with her again.”

Olcott did, however, direct a number of films financed by Hearst. “I believe Hearst understood the situation without being told,” said Vignola, “and he was showing that understanding by giving Sid some fine films to direct.”

Stars were clamouring for Olcott to be their director. He was reported receiving $5,000 a week in the middle 1920s, a huge amount for that era.

George Arliss, the renowned English actor, gave the performance of his life in The Green Goddess. “I stood in amazement as Sid Olcott created a character for me in front of my eyes,” he said. “He gave me a power of expression I was not, until that time, aware I possessed. He was a brilliant, firm, yet never abrasive, director.”

Gloria Swanson worked with Olcott in The Humming Bird. “Sid was,” she said, “tough, yes very tough, but a magnificent director who taught me a great deal about true acting. The simple truth is that he was a better actor himself than any he ever directed.”

Norma Talmadge, directed by Olcott in The Only Woman, said, “I love him. I worship at the shrine of his brilliance.”

Pola Negri, star of The Charmer, said Olcott was “unique, totally dedicated to getting the best out of every performer. He paid the same dedicated attention to the small-part actor or actress as he did to the star. It made filming very easy for all of us.”

Warner Baxter, directed by Olcott in The Best People, said, “A genius. So patient, kind but firm in his determination to accept nothing but excellence from an actor.”

Richard Barthelmess signed Olcott to a three-picture deal in 1926. He was to be paid $8,000 a week for each week of shooting and $5,000 a week for each of three weeks for preparation and rehearsal. “Olcott was a man of great integrity,” said Barthelmess. He finished all three films a week early, thus losing $24,000. He could have stretched them out but he didn’t.”

Ransom’s Folly, The Amateur Gentleman, and The White Black Sheep were all big successes for Olcott and Barthelmess. The actor had a long and lucrative career, retiring to a beautiful Long Island estate. One year before his death in 1963 he spoke of Olcott. “I owe him my career and my success. That I was able to retire to this magnificent estate is a tribute to his remarkable work. In 1926 he taught me more about acting than I had learned in my entire career. Sadly, I was not aware of his death in 1949 to pay my proper respects. Perhaps what I say now may in a small way make amends.”

Shortly after Little Old New York was released, Olcott was pressured, against his better judgement, into directing Rudolph Valentino in Monsieur Beaucaire. He and Valentino’s wife, Natasha Rambova, were at loggerheads from the first day of shooting. “The woman is a total idiot,” Olcott told producer Adolph Zukor. “She knows nothing yet tells Valentino how to act and me how to direct. I want her off the set.”

In a biography of Valentino, Zukor tells how he used dozens of pretexts to keep Rambova away from Olcott. The result was a film in which Olcott obtained, said the New York Times, the best acting of Valentino’s career. The movie opened in New York, where it was filmed, and broke box office records across the country.

Olcott refused to work with Valentino again despite pleas from the great screen lover. “I told him bluntly,” said Olcott, “that I objected to his uncalled for advances and that since I was not permitted to damage his pretty face I would kick him you-know-where if he didn’t cease pestering me. Can you believe this poof came and sang love songs outside my hotel window in New York!”

In 1927 Olcott made just one film, The Claw, starring Norman Kerry. He then announced his intention of sailing for England “to spend twelve months making films in London for the British Lion Company.” George Arliss, who had arranged the contract for Olcott, met Olcott and his wife when they arrived in London. At a press conference at the Savoy Hotel, Olcott described the coming twelve months as “the opportunity of my life. I shall be working with many of England’s greatest actors.”

But Olcott was to be disillusioned. Shown the town by Arliss and his wife Florence, he wrote to Robert Vignola that “I wonder every night why I waited so long to film the enchanting scenery that startles and astounds me at every bend in the road.” Before the letter was even delivered, the film industry papers in Los Angeles headlined a story from London. “I will not be directing in England,” said Olcott. “I will not be part of films which glorify crime and criminals. I am suing British Lion Films.”

The Olcotts stayed long enough to win their lawsuit. The British court agreed Olcott had been falsely advised as to the nature of his work, and awarded him £10,000 (approximately $40,000 at that time) in damages.

When the Olcotts arrived home in October 1927, a pile of requests for his services was waiting on his desk. Shunning them all, he called a press conference and announced his total retirement.

“I am officially retired as from this date,” he said. “I have no plans to direct any more films or to be further associated with the industry with which I have been involved for more than twenty years. This is my irrevocable decision.” Declining to answer any questions from the reporters, he left the room. And, as one story ends, “leaving Mrs. Olcott and two maids to serve tea and sandwiches.”

Never again did Olcott pass through the gates of any Hollywood studio. He welcomed show business friends to his home, but would never discuss the industry. His closest friend, Robert Vignola, said, “Even I am not permitted to talk about the films I am directing.”

Years later it was revealed by George Arliss that he had convinced Olcott, in 1929, to give him personal coaching for his roles in the sound remakes of The Green Goddess and Disraeli. “We went through both scripts many times,” said Arliss. “Valentine or Sid took the roles opposite me. We worked together for more than three months before I felt I was ready to face the cameras.”

When the Oscar nominations were announced, Arliss received a unique honor. He was nominated for the Best Actor award for both films. His role as Disraeli won the award. In London, where he was filming on awards night, Arliss told the Daily Express that “I owe everything to Sidney Olcott. His was a remarkable feat. He directed this actor without entering the studio and without any official credit.”

In the 1930s Olcott and his wife spent several summers in Ireland. In a small community just outside Cork he designed and paid for the construction costs of a chapel in memory of his parents. Some clippings in the British Film Institute suggest he did direct at least one film in Ireland, but no available records show his name as director.

During World War Two he opened the doors of his Beverly Hills mansion to servicemen and women. Every service club in the area was asked to notify him of visits by members of the forces visiting from Canada.

With the doors of Pickfair, where Mary Pickford reigned supreme, also open to Canadians, most servicemen and women headed there and ignored the Olcott invitation. His fame from the silent era was forgotten. Pickford and others still in the limelight were the magnets for service personnel. Those who did call Olcott and his wife were picked up by car from wherever they called and entertained royally.

Those who became Olcott’s guests found a call from him to giants of the industry like Pickford, Mayer, or Warner opened doors that were closed to most people. Those who stayed a few days were occasionally shown some of the silent films Olcott had directed. Often accompanying the films on piano was the classical pianist Jose Iturbi, a neighbor and friend of the Olcotts. “My first job as a pianist was playing for silent films,” Iturbi would tell the guests. “I loved it then, I love it now.”

Sidney and Valentine Olcott lived in comfort. They had a gardener, a chauffeur, two maids, and a butler who came in each evening to serve dinner. Among their friends were stars like Cary Grant, Katherine Hepburn, Humphrey Bogart, Alan and Sue Carol Ladd, and Charlie Chaplin. The latter brought over his own films for Olcott’s fascinated guests.

But Olcott never boasted of his own important role in the growth of the film industry. He took a back seat to the stars who were constantly in and out of his doors.

After the war, Olcott and his wife lived quietly. Their visits to restaurants ceased. Dining out with friends became more and more infrequent.

On March 12, 1948, Valentine Olcott died peacefully in her sleep. Olcott’s last public appearance, at seventy-five, was to attend her funeral. Within a month he had sold his Bedford Drive home and moved to the home of Robert Vignola, his friend from the beginnings of the film industry. Vignola’s wife had died on February 15, 1948, and he, like Olcott, was alone.

Olcott and Vignola remained in seclusion, with a house staff of five, until Sidney Olcott died on December 16, 1949.

“He had little to live for when Val died,” Robert Vignola told the New York Times. “He just went to bed and died during the night. A great man whose fame is of yesterday. Sid Olcott showed hundreds of people the way to fame and success. I, and many others, will not forget.”

Unhappily, most had. Less than 100 people attended the funeral service. In addition to Vignola, friends like Joseph and Fred Santley, George Melford, Herbert Brenon, and George and Alice Hollister were there to pay their last tributes. Only Jean Hersholt and Pat O’Brien were there to represent those still active in the industry.

This time the eulogy was brief. Robert Vignola said of his friend: “A friendship with Sid Olcott was a friendship for life. A friendship with Sid Olcott was something to be cherished. A friendship with Sid Olcott is something many of us hope to renew in the life hereafter. For eternity!”

Despite his long years of inactivity, Olcott died a wealthy man. His estate, in excess of $250,000, was divided among a few friends, with provisions for life annuities for many of his house staff including some who had retired years earlier. The American Cancer Society, the Salvation Army, the Motion Picture Relief Fund, and the Institute for Medical Research at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital all benefited from his generosity. In his will, made just one month before he died, he requested that one bequest be paid before all others. The sum of $5,000 was to go to the Boys’ Home in Toronto.

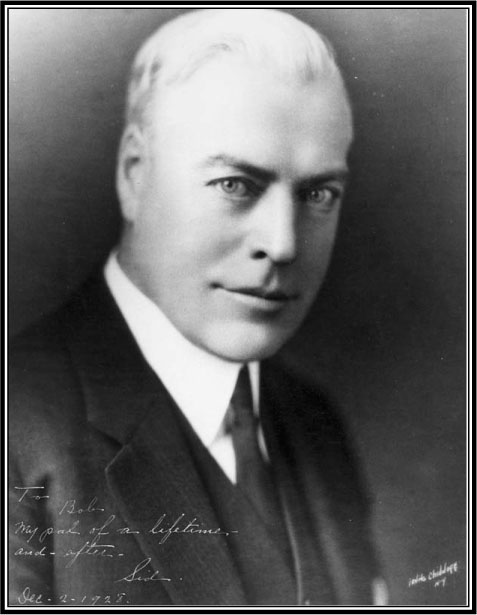

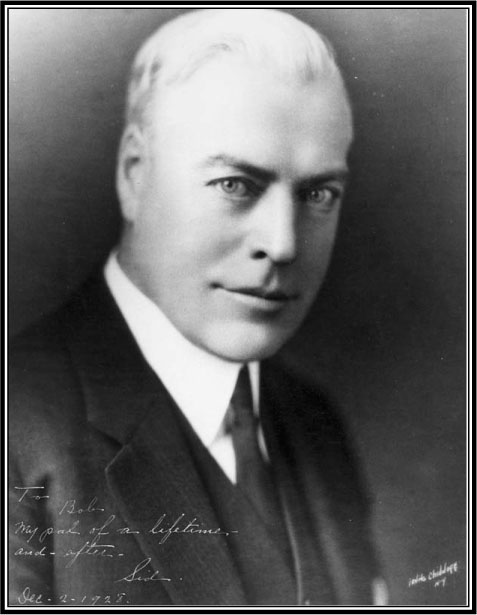

Sidney Olcott

A codicil to his will, added only days before his death, asked that his body be sent back to Toronto for burial in the cemetery where his parents lay. “I love Canada,” he had added at the bottom.