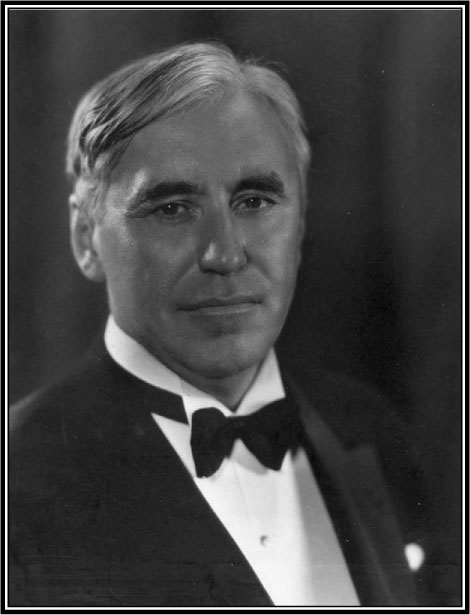

“Mack Sennett had a feeling for comedy that has never been equalled. He knew precisely what the audiences in those early days wanted. Unhappily, his inability to sense the subtle changes that were taking place in public tastes, led to his downfall. If we could have had only silent movies forever he would still be the world’s King of Comedy today.”

(Charlie Chaplin, 1956)

Ironically, only eleven years after making his comment about Mack Sennett’s inability to keep up with the public’s needs, Chaplin made a similar statement about himself. Two sound films, A King in New York and Countess from Hong Kong, which he made in England after his exile from the United States, were failures at the box office.

“I should have learned how to change with the times,” he told the London Daily Mail. “I had some of the finest actors in the world [Marlon Brando, Sophia Loren, Margaret Rutherford] at my command in these films but I didn’t know what to do with them when words counted more than actions!”

Silent films where actions counted more than words were also Mack Sennett’s forte. No one ever disputed his ability to produce the best comedy films when slapstick was the thing. More than 1,000 silent films, mostly one-and two-reelers that lasted only ten or twenty minutes, bore his name in the credits. He also made many two- and three-reel sound films, and a few full-length features. Some of these longer films were successful but most, unfortunately, were not.

Certainly no one today can question Sennett’s ability to unearth potential talent. Chaplin said many times that it was Sennett’s wisdom and vision of what might be that took him out of Fred Karno’s British revue, A Night in a London Music Hall, touring the United States in 1912. It was at Sennett’s Keystone Studio in Hollywood where Chaplin made his first thirty-five short films and where he created the “tramp” character that became his trademark for more than four decades.

The list of stars, of both silent and sound eras, given their first opportunity by Sennett can be gauged from this partial list of former Sennett discoveries who attended a party he gave, in 1932, to celebrate his twentieth year in Hollywood. Those present included actors Edgar Kennedy, Wallace Beery, Chester Conklin, Slim Summerville, Harry Langdon, Bing Crosby, W. C. Fields, Louise Fazenda, Monte Blue, Mae Busch, Eddie Quillan, Oliver Hardy, Stan Laurel, Edna Purviance, Gloria Swanson, and Charlie Chaplin.

Directors and producers present, who learned their trade under Sennett’s guidance, included Lloyd Bacon, Eddie Cline, Wallace McDonald, Del Lord, Frank Capra, Roy Del Ruth, and Eddie Sutherland.

But when Sennett died at the age of eighty, in 1960, he had spent most of his last ten years living alone in a small apartment overlooking Hollywood Boulevard. Only occasionally did a few of the friends he had made in his days of glory pay him a visit.

Mack Sennett was born Michael Sinnott, in Danville, a small town close to Montreal, Quebec, on January 17, 1880. His father was the manager of a small hotel. His great grandparents had emigrated from Ireland a century before Sennett was born. His mother, he used to tell people proudly, provided the rich people of Danville with the “finest and whitest laundry in all of the Province of Quebec.”

His education was far from being as limited as many writers have suggested in magazine articles and biographies over the years. He graduated from school at sixteen, top of his class, with honours in mathematics and English. “I was quite a whiz at chemistry, too,” he said. “In fact, when I left school I had two ambitions. One was to be a research chemist. The other was to be a singer.”

He never pursued the first dream, but by seventeen, although his speaking voice was normal for a boy his age, his singing voice was a robust bass, and he was often featured as a soloist in church and other choral groups around the Montreal area. “There was such a dearth of entertainment in Danville that we quite looked forward to one of the old-timers of the town dying,” he said. “The wake could sometimes last a week and I always got to sing.”

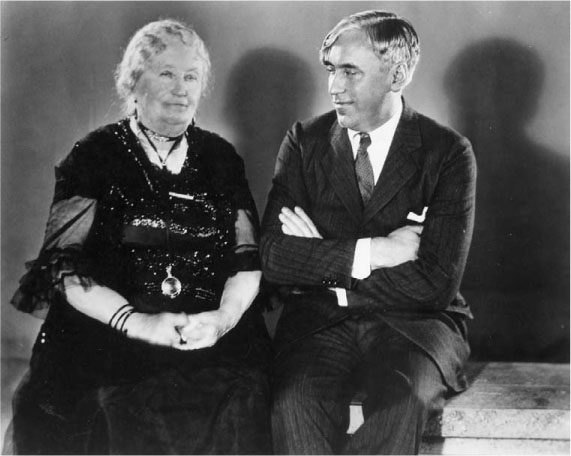

Mack Sennett with his mother.

His second dream received a boost when his father received a lucrative job offer from a construction company in East Berlin, Connecticut. “I have never been quite sure what his qualifications as a hotel manager had to do with building, but he got the offer and we moved.”

“I think everybody sang in East Berlin,” he told Film Weekly in 1928. “I was in big demand with my bass voice. So I renewed my dream of becoming not only a professional singer, but a professional singer in opera, perhaps even at the Metropolitan Opera House.”

But singing at concerts and in choral groups wasn’t making any money for the Sennett (Sinnott) family, so he found another job. “I was over six feet tall, weighed 220 pounds, so where do you think the labour exchange sent me? Where else but the American Iron Works in East Berlin, where I quickly learned to move iron castings, which weighed two hundred pounds, from place to place. I also learned not to go too close to the smelting areas. I still have scars on my hands to show where I got burned,” he said.

In East Berlin Sennett got a big boost for his operatic ambitions. The family purchased a large house so that his mother could take in boarders. “We had six or seven at a time and one of these boarders was a big contrast to the rough labourers who were the standard fare. The little man who arrived at our door one evening and stayed until we left town introduced himself as Signor Fontana. He wore a frock coat and, on occasions, a top hat. I earned his undying gratitude when I used my size and weight to stop the other boarders from kicking his hat around the room.”

Signor Fontana turned out to be a vocal coach. “I imagine his real name was Joseph Brown, or something like that,” said Sennett. “But it didn’t matter to me what he was called when he offered me free voice lessons in exchange for free meals. We couldn’t rehearse in the house because of the other boarders. I should mention that my bass voice when fully let loose is something rather like a bull moose in heat. So we went into the woods away from the houses and I received my first training there.”

Rehearsals had to be moved to the local church hall when Sennett and Fontana heard rumours that some of the locals were planning a moose hunt in the woods near the town. “One of the boarders said they had heard several times the call of a female moose and where there was a female there must be a male.”

The church hall belonged to the Baptists of the community, much to the dismay of Sennett’s parents. “We were good Roman Catholics,” recalled Sennett. “And to step foot in even a Baptist Church hall at that time was enough to get the entire family thrown out of our regular Sunday place of worship. Fortunately, we had a very understanding priest who agreed I could train in the Baptist building if he was permitted to say a few prayers in the hall to ensure my soul wouldn’t go you know where.”

The Sennett (Sinnott) family moved to Northampton, Massachusetts, in 1900. “We had a bit of money saved from the boarding house, my foundry work, and my father’s construction job, so he decided on the move because he had a chance of a partnership in a contracting firm there. I wasn’t aware at the time that Signor Fontana was eagerly pushing for the move. He had quietly told my mother, perhaps rather sarcastically, that ‘Michael needs a much more experienced coach than me if he is to sing at the Met.’”

Years later the priest from East Berlin, visiting Hollywood at the invitation of Sennett’s mother, told him, “The good signor told me his ear drums were bursting from your bellows and he would be totally deaf if he had to listen to your singing much longer. And I fully understood, Michael. You will recall that we had to place you on a platform in the church, slightly higher than the rest of the choir. That was because so many of our singers were reporting constant earaches after the services. So we solved that by letting your voice rise gently, if that is the correct word, over their heads.”

Sennett said that the remark was one of the most upsetting he had ever experienced. “Thank you, father,” he told the priest. “I thought I was being chosen to stand out because my voice was so magnificent.”

In Northampton Sennett chose the Northampton Iron Foundry as a place of employment. It may well have been the most important move in his career. “The manager of the foundry was also a part-time actor in one of the local amateur companies,” he said. “He used to rehearse his lines in the lunch break and he would ask any of us around at the time to read the lines of the other characters. I enjoyed playing the different roles and one day he invited me to join him at the theatre, where they were casting for the next play.”

Before he knew it, Sennett was on stage playing role after role in everything from comedy to melodrama.

“I loved every minute of it,” he said. “I soon found myself playing the lead comedy parts. I learned the art of timing my lines in that little theatre.

“In the melodramas I rarely got a line unless it was as a butler announcing a guest. Even then the audiences laughed because it came naturally to me to create bits of business that weren’t in the script. The director encouraged me, and the audiences liked my style so well that week after week I got a round of applause when I made my first entrance in a play, often before I’d said a word.”

Sennett was quick to point out that it was an amateur company and no one got paid. “We always got full houses for the plays,” he said. “There was only one other place of entertainment in the town, the Academy Theatre, where sometimes the shows were first class, more often than not they were third-rate. We often outdrew the professionals at the box office, but that may have been something to do with our prices. Our top was 15 cents, compared to the Academy’s dollar or even $1.50.”

The money taken at the door was used to provide summer picnics for local children. “We spent a few bucks on a party at the end of each play, but most of the money went where it was needed most,” he recalled. “I used to dress up as a clown and go to the summer picnics. I shall never forget the looks of delight on the faces of the children when I made them laugh.”

In 1902 a chance encounter with one of the most renowned entertainers of the day led him to the start of a career in New York. “Marie Dressler, who had been appearing on Broadway for several years, was on a national tour with one of her plays, Lady Slavey, when she was booked into the Academy Theatre,” he said. “You can judge her importance from the fact that her play was advertised as staying two weeks. Most of the companies staying only one week had to provide a different play every second night.”

Sennett was playing the lead in a very funny play when he heard an unusual noise from the audience. “I thought I had a loud voice but all through the play I could hear a raucous laugh high above all the others coming from the back of the theatre. It was so infectious it had everyone else roaring with laughter and I had the most successful night of my amateur career.

“I asked one of the company to see who this loud-voiced person was, and he came back and said, ‘You’re never going to believe it, Mike. It’s Marie Dressler from the Academy Theatre show.’ I was stunned. Marie Dressler, laughing at me? She was only the best comedienne in the country at that time. I had heard that the Academy was having heating problems and might have to close for a day while the trouble was fixed, but I never dreamed Marie Dressler would come to see our little show. I couldn’t imagine I’d ever meet her, but after the final curtain came down she came backstage and asked to meet me. Me, can you imagine? She asked to meet me.

“I was rather overwhelmed by the presence of the great actress, but she quickly put me at ease. ‘You gave a wonderful performance,’ she said. ‘Have you ever considered becoming a professional actor?’ I told her I hadn’t, but I would from that day on. She handed me her calling card. On the back she wrote the name and New York address of one of Broadway’s most important producers, David Belasco. ‘Go and see him,’ she said. ‘Tell him I sent you. Tell him I want him to find you work in the professional theatre.’ On the front she had written, ‘This will introduce my friend, Mack Sennett.’ That’s how she must have heard my name when she asked who the comic in the play was. I didn’t like to tell her she had my name wrong. I figured I could tell Mr. Belasco if I ever got to meet him.”

The young Northampton lawyer who accompanied her to the show handed over his business card and urged Sennett to let him read any contracts before he signed them. “When I saw the name on the card I realized it was the man everyone was suggesting would be the next mayor of the town. When I was ready to have him read my contracts he was no longer in business as a lawyer, having become the governor of Massachusetts. He went on from there to become the president of the United States. His name was Calvin Coolidge.”

Dressler gave Sennett a great big smile, kissed him on the cheek, and wished him well. “Then she swept away with all the majesty and dignity only a really big star, like she was, could exhibit,” he said. “Let me tell you something, all my life I’ve remembered that exit and longed to make just one, somewhere, sometime, like it. But I never will now. Every exit I make has to have a pratfall in it so the audiences will laugh.”

Dressler’s visit had Sennett hooked. Two weeks later he told the foundry manager he was leaving to try for fame and fortune on the Broadway stage. “Everyone wished me luck, even gave me the door take from the last night of our show. I can’t remember, but I think it was about ten dollars. I’d saved about thirty more, so I headed for New York.”

David Belasco was out of New York when Mike Sinnott, soon to be Mack Sennett for the rest of his life, arrived at his office three weeks later. “I’ll make you an appointment to see Mr. Belasco next week, Mr. Sennett,” said his friendly receptionist. “If Miss Dressler sent you I know he’ll want to meet you.” And she added, “Mr. Sennett, if you don’t mind my suggesting this, I think you should buy a new suit for the interview. Mr. Belasco likes his actors to be well dressed.”

Sennett spent a few dollars from his meagre savings as the receptionist suggested. “I even went to a first-class barber, close to the theatrical boarding house where I had found a room, and got myself a real stage haircut. When I looked at myself in one of the store windows on 42nd Street I felt I was already on my way to becoming a Broadway star.

“One of the actors in the house where I was staying, a gruff-looking character actor, brought me down to earth with a bump when he looked me over and told me my Massachusetts shoes just weren’t good enough for Broadway. I must have looked a little taken aback, for I was already running rather low on funds. I’m sure he could tell. ‘Here,’ he said. ‘I’ve got a spare pair. You can have them.’”

Sennett recalled retiring to his own room to put on the shoes. “I had to get away,” he said. “I was so overwhelmed by his generosity that tears were streaming down my face.”

Mack Sennett was to meet up again with his benefactor some fifteen years later in Hollywood and was able to repay the kindness without the actor ever realizing that he had met Sennett before in New York.

Sennett kept his appointment with Belasco. The renowned producer looked him over. “Miss Dressler says you are a good comedy actor,” he said. “She has impeccable taste, so I must believe her. But I think you need some solid grounding in the art of comedy before you will be ready for Broadway.”

“He directed me to the burlesque houses that were plentiful in New York at that time. I had never seen burlesque, didn’t have any idea what it was, but presumed that if it was endorsed by Mr. Belasco it had to be legitimate. So I went to the Bowery Burlesque Theatre and had my eyes opened. If this was New York theatre I could be a star very quickly. In fact, I could even teach the comics a thing or two!”

Sennett returned to his boarding house and buttonholed several of the residents. “How do I get into burlesque?” he asked. “Easy,” said one haughty actor, “you lower your standard of morals to theirs, you walk in the stage door, trip over the stage door keeper’s outstretched leg, and when you get up there’ll be someone waiting to give you a contract.”

“It was quite a while before I realized he was just being sarcastic and couldn’t possibly imagine why anyone would sink low enough to want to be in burlesque,” he said. “But I had enjoyed what I saw. The comics were funny. The ‘bump-and-grind’ strippers were appealing, though rather fat. But I just couldn’t understand why the sopranos and tenors were booed. To me they sounded quite good enough to be at the Metropolitan Opera House.”

One story Sennett told that never varied over the years is the tale of his New York debut. “I found out where the Bowery Burlesque actors ate and haunted these places, picking up bits of conversation and quite a few new friends who were not unhappy when someone bought them a sandwich and coffee. I was getting down to my last few dollars when one of my new friends told me there was a job opening at the Bowery. I raced over to the theatre and asked for the man my friend said could give me a part in the next week’s show.

“He told me they were looking for a dumb-looking character who would walk across the stage several times each show brushing imaginary dirt off the floor. I used my deepest voice when he asked me to try out my one line. It got me the job. I had to say, looking at the audience, ‘and they call this a one-horse town.’ I was astounded how the audience loved the line so I started adding bits of business to my character. After I’d said my line I pretended to trip over some invisible horse droppings and did a somersault into the wings. When they applauded I sneaked back and showed my head around the scenery. How many other people can say they stopped the show in their New York debut?”

The second week was rather a letdown for Sennett. “The only thing they had for me was the hind end of a horse,” he recalled in 1943. “I needed the money so I got dressed up every night for the role. Even though my face was never seen I joined the rest of the gang in the big dressing room every night before the show and put on my make-up. Why not! I was in the professional theatre.”

Unfortunately for Sennett, his second week in the “big time” was the week the police decided to raid the Bowery Burlesque Theatre. “Every last one of us was herded into paddy wagons and away we went to the police station. They kept us in cells all night without charging us. Next morning we were called up before the judge. He listened to the evidence of police officers who had obviously been thoroughly enjoying the show since they didn’t raid us till the final curtain came down. The strippers were fined a dollar or two. Some of the comics were fined for ‘lewd jokes.’ But when I arrived in the dock in my horse’s-ass costume the judge was obviously rather bewildered.”

“And what do you do for a living?” he said.

“I’m an actor,” I replied. “A character actor, sir.”

“And what character are you supposed to be in that get-up?” he asked.

“I’m part of an animal, sir,” I said.

“What part of what animal?” he asked.

“The ass-end of a horse, sir,” I said.

“Now make up your mind, Mr. Sennett. Are you an ass or a horse?” he enquired.

“A horse’s ass-end,” I replied.

Sennett always swore that he saw a glimmer of a smile on the judge’s face, and decided to play the moment for all it was worth.

“Actually, I’m going to be an opera singer, sir,” I said.

“I can’t quite see the point in this type of training,” said the judge, “but then I have never been to the Bowery Theatre.”

To the arresting officer he said, “Is there any evidence that this man spoke lewd or indecent lines on stage?”

“No, sir,” said the officer, “but he did fart twice rather loudly during his second on stage appearance as the horse.”

“Could you distinguish, officer, between the front and rear ends of a horse, and which of the two actors expelled the air?”

“Well,” said the officer, “not really, sir. It’s simply my judgement.”

“I’m afraid your judgement isn’t enough to convict this man,” said the judge. “Not guilty,” he said, and added, “If I were you, Mr. Sennett, I would try to find a more suitable place in which to enhance my singing career. Case dismissed.” Sennett later swore the judge winked at him as he left the dock.

Sennett’s ventures into the world of burlesque kept the wolf from the door. “I had to eat,” he said, “and if it meant doing pratfalls on the burlesque stages that were plentiful in New York at the time, I never argued and in fact learned a lot of stage tricks I used many times later in films. A lot of great comics came out of burlesque, as did so many of the great comedy routines. Some of them will last as long as there is any comedy left in the world.”

At this stage in his career Mack Sennett was still determined to become an opera singer. When he had a few dollars saved up he used it on singing lessons. “More than one studio threw me out,” he recalled in 1943. “I was loud, I admit, but to throw me out without giving me my money back, that hurt.”

In 1906 he said farewell to his dreams of becoming a vocal star. “I was in a Professor Valmar’s studio one day and heard him finishing his tuition of another singer. I listened and was bewitched by the superb tone and range of this unknown tenor. When the professor came out to me I commented on the magnificence of his earlier pupil’s voice. It was, I said, surely good enough to have won him a place in the Metropolitan Opera Company. ‘No,’ said the professor. ‘As a matter of fact he works every night in a restaurant, just off Broadway, as a singing waiter.’

“It was at that moment I decided to abandon my voice training. If he, with a voice like that, could reach no greater heights than a cafe, what hope had I?”

For two years Sennett stayed in the world of burlesque. “Frank Sheridan, who ran a touring burlesque show, gave me my first chance to become a real comedian. I was allowed to put my own ideas into well-worn skits and before I knew it I was actually writing comedy skits of my own,” said Sennett. “I travelled with Sheridan’s Burlesque company as far west as Chicago before we headed back east. I dreaded the day when we would reach Boston. I knew all my relatives would all be there to see me perform. By now I had convinced them, in my letters, that I was a big star. I dreaded what they would think.”

The day finally arrived. “Before we opened in Boston I asked Frank if he could tell all his comics to play down the crude jokes just for one night, and ask his ‘bump-and-grinders’ not to be quite as suggestive in their movements as usual. I even rewrote my own skits to take out anything that might offend my family,” he recalled.

Everyone co-operated but the audience. They sat on their hands and there wasn’t a single belly laugh that night. “My own skits went totally flat,” Sennett remembered. “I waited after the show for my family to come back stage, but no one arrived. Oh, my, I thought, has even this tame show offended them? I went back to my theatrical boarding house almost in tears.”

Next night the word went out from the theatre management to Frank Sheridan. “No more white-washed shows,” they said. “We won’t have an audience by Saturday if you put Monday’s show on again tonight.”

“So we all went back to our regular routines, and the audience laughed and cheered everything we did. After the final curtain I went off stage and was stunned to find my parents and sister waiting for me. For a minute I was horrified at what they must be thinking. Then my mother spoke. ‘Michael,’ she said. ‘That was surely the funniest show we have ever seen. We have never laughed so much in our lives. And those beautiful dancing girls [the bump-and-grinders] were so delightful. You must have a very difficult job deciding which one to choose as your girlfriend.’”

Sennett said he was relieved when his parents left to go home to Northampton. “I kept waiting for the bubble to burst or that I’d wake up and find I’d been dreaming. But it didn’t happen.

“Next night Frank Sheridan and his wife stopped me on the way to the dressing rooms. Frank asked how my parents had enjoyed the show. I told him their reaction, and he laughed. ‘It was the same when my parents first came to see me,’ he said. ‘They loved the show and I’ve come to the conclusion that everyone, no matter what their upbringing, will laugh at down-to-earth comedy.’ I remembered that many times, years later, when I questioned the prudence of some comedy routine I wanted to put in my movies.”

Sennett hung around New York for the next five years. Occasionally he got small parts in the legitimate theatre and by 1905 was auditioning for parts in Broadway musicals.

“One of my first attempts to get into the big time was at an audition for the musical, King Dodo, starring Raymond Hitchcock. The director liked my voice but said he had only one thing to offer, a place in the dancing and singing chorus. Chorus boys with deep bass voices were then, as they are now, hard to find and I was told I had the part until Hitchcock saw me rehearsing one of the dance routines. ‘Remove that bumbler,’ said Hitchcock. The director protested. ‘We can improve his dancing, but just listen to his voice.’ ‘Fire him,’ said Hitchcock. ‘We don’t need singers that badly. With him in the show Broadway’s very existence is in peril.’”

Years later, when Sennett’s New York partners insisted that he hire Hitchcock at $2,000 a week for the movies, he protested but was overruled. But Sennett got his revenge. After a week at the Keystone Studios Hitchcock asked to be released from his contract.

“I made his life so miserable,” recalled Sennett, “that he said he hated and despised filmmakers. I accepted his resignation and as he left the studio I yelled after him, ‘If you’d been able to dance, Mr. Hitchcock, I wouldn’t have let you go.’ He had no idea what I was talking about.”

Hitchcock didn’t make another film for seven years, and his movie career was short and unspectacular. But he did return to Broadway for considerable success.

Sennett persevered with his attack on Broadway. He took dancing lessons and eventually made his Broadway debut. “After spending all that money on dancing instruction I was hired as a singer,” he said. “The show was A Chinese Honeymoon, with Thomas Seabrooke as its star. All my vocal coaches had complained that my diction was poor, but it stood me in good stead in A Chinese Honeymoon because all the singing had to be done with a Chinese accent. Seabrooke commended me for the authenticity of my delivery, and recommended that all the rest of the singers should listen carefully and try to reach my perfection.”

He worked in a number of other Broadway plays, often as a minor comic, but his great moment arrived when he was chosen to read for a part in the play, The Boys of Company B. The play starred John Barrymore, then in the early stages of a great career that was to last until his death at the age of sixty in 1942.

Sennett got a two-line part in Barrymore’s play. “He was just back from a tour of Australia and from the look of him he’d celebrated far too much and far too often while he was down there. He was only about twenty-five but he looked like a man of fifty. After having me parade across the stage two or three times he asked me only two questions. ‘Are you Irish?’ he asked. I told him my ancestors were. ‘Do you drink the hard stuff?’ he added. I told him I did not, which was a lie. ‘Good.’ he said, ‘you’ll only be on stage for a few minutes at each performance so I’ll expect you to make a note of all my exits and have my glass filled and ready every time I leave the stage. Can you do that?’ I needed the money so I told him I could. ‘Very well,’ he boomed. ‘Then you’ve got the part.’”

On the last night of the play Sennett recalls tripling the quantity of liquor in the glass for each of Barrymore’s many exits. “By the final scene he was rolling about the stage like a drunken sailor and for one night, at least, we had a comedy hit.”

When the Barrymore play closed after twelve weeks, Sennett decided to try David Belasco’s office once more. “I was surprised that he remembered me,” said Sennett to Film Weekly in 1925. “He seemed pleased to see me, even got out of his chair and greeted me like I might have been one of Broadway’s biggest stars. ‘Well, Mr. Sennett,’ he said. ‘You haven’t been setting the world on fire since I last saw you, but you couldn’t have come in at a better moment. I have something for you.’ I thought for certain I was about to be given the starring role in one of his plays, but my ego was sadly deflated when he told me he would like me to go out to the Biograph moving picture studio. ‘They need actors out there with Broadway experience,’ said Belasco. ‘Just tell them I sent you and that you’ve just completed a twelve-week season with Barrymore. Tell them I consider you an actor with great potential for the pictures industry.’”

In 1909 few of the actors at Biograph could claim to have had Broadway experience, or any experience at all, for that matter, and he discovered Belasco was right when he arrived at the studio at 11 East 14th Street. “I arrived there at ten o’clock in the morning and at ten thirty I had completed my first part in a film,” recalled Sennett. “By the end of the afternoon I had played three more characters. I have no idea if they were part of the same film or three different ones. I lined up at the end of the day with all the others and was paid five dollars for my efforts.”

“Can you come back tomorrow? In fact we can probably use you every day this week,” said the director. He added, “We only pay $20 for the five-day week, is that acceptable?” “I told him it was,” said Sennett. “It wasn’t until Friday when I lined up for the $15 balance of my salary that I learned his name was D.W. Griffith.

“The first night I rode back into the city on a streetcar with another young Canadian who was just getting her feet wet at Biograph,” he said. “Her name was Mary Pickford. I discovered David Belasco had also sent her to Biograph.”

Within weeks of his arrival at Biograph, Sennett was playing important roles as the villain opposite some of the most important actresses on the studio payroll. They included Linda Arvidsen (then D.W. Griffith’s wife), Mary Pickford, and Florence Lawrence. It was at Biograph that he first met Mabel Normand, who was soon to become the most important woman in his life.

Between 1908 and 1911 Sennett sold more than 100 script ideas to Griffith, mostly comedies. In 1910 Griffith pushed him into his first directing job when another director became ill. That same year he travelled with Griffith and a small group of actors to California where he stayed six months before finding he missed Mabel Normand too much. “I told Griffith I was heading east,” he said, “and he didn’t protest too much.”

Talking to Film Weekly in 1928, D.W. Griffith saw Sennett in a different light. He said, “It was Sennett’s great curiosity about everything to do with motion pictures that made him so indispensable to me. He would investigate the lighting, even help put sets together. On occasions, he actually advised me how to shoot a scene. I wouldn’t have told him so at the time but I actually listened. He told other actors how to stand, where to stand, and what moves to make to get the maximum effect. It was especially obvious that he knew instinctively what would be funny and what would not. When I decided to give him a chance to direct a film by himself he showed remarkable maturity for one who had been in the industry such a short time.”

Billy Bitzer was probably the greatest cameraman from the silent era. He worked with Griffith from the early days of Biograph and stayed with him to the end of his career, filming his major successes including Birth of a Nation and Intolerance. Bitzer said in a Film Weekly article in 1940 that he had once considered leaving Griffith to go with Sennett when he left Biograph to form his own company.

“Griffith rarely gave other directors an opportunity to work on their own, and when he offered Sennett a chance to direct some comedies, he asked me to be his cameraman,” said Bitzer. “I was very impressed by the way he coaxed the humour out of actors who didn’t look like they had an ounce of humour in them. It was obvious that he was going to be a great director, different in style completely from Griffith, but he had a quality that could not be denied. I enjoyed working with him. He stood no nonsense from anyone. He wasn’t afraid to tell actors or technicians, including me, if he thought we weren’t getting the most out of a scene.

“When he told Griffith in 1912 that he was planning to form his own company I considered quite seriously accepting the offer he made me to join his Keystone Film Company. The money he offered was more than Griffith was paying, but I had a gut feeling somehow that my career would be more memorable with Griffith, so I stayed, and, of course, I have never regretted that decision.”

To finance his new company, Sennett entered into an association with two former racetrack bookmakers who were, in 1912, running a successful film distribution house. In Sennett’s autobiography he claims that he was forced into taking the two as his partners because he owed them a $100 gambling debt.

Many people, including the two former bookies, Charles Bauman and Adam Kessel, have denied this. “Sennett needed money,” said Kessel, “so Bauman and I agreed to finance his new company. He agreed that he would use our old Bison studio, near Los Angeles, where we had been making western films for our distribution house.

“He took a third share in Keystone, and we each took a third. Sennett didn’t put any money in the pot, he got his share for contributing his knowledge and experience in film production. We even agreed to buy the rail tickets from New York to Los Angeles for himself, Mabel Normand, the Biograph actress who was now his girlfriend, and actors Fred Mace and Ford Sterling.”

Sennett said in 1943 that he, Sterling, Mace, and Normand didn’t waste a minute of the six-day rail journey across the United States. “Even though I was the only one who had ever seen California I was able to describe the wonderful scenery to them, and by the time we arrived in Los Angeles we had the basic ideas prepared for more than fifty different films.”

One of Sennett’s favourite stories, which he told many times over in the years that followed, was that they started shooting their first film fifteen minutes after they stepped off the train. “There was a big Shriners parade going by the railway depot so I dashed into a store, bought a doll, and wrapped it in a shawl belonging to Mabel. I made her run up and down the line of Shriners as if she was desperately trying to find the father of her baby,” he said.

“The Los Angeles police joined in the chase, trying to catch Mabel. That was where I got my idea for the Keystone Kops. Two days later we finished the film in the Bison studio and had it ready for the film exchanges a week later. We never dared show it in Los Angeles. Too many Shriners and city cops might have recognized themselves.”

Several film historians have doubted the truth of this story, and Adam Kessel said many years later that he agreed that Sennett’s memory was faulty. “The story is a figment of Sennett’s imagination. They had no camera with them and couldn’t have got hold of one until the next day when they arrived at the Bison studio,” he said.

The old Bison Films studio, located at 1712 Allesandro Street [now part of Glendale Boulevard] in Edendale, a suburb of Los Angeles, was discovered by Sennett to be nothing more than an old grocery story that Bauman and Kessel had bought two years earlier.

Mabel Normand told Film Weekly in 1929 that Sennett brought in construction workers twenty-four hours after they arrived in Los Angeles. “He had no money to pay the workers or even buy the materials for the buildings he planned, but somehow he charmed the workers into waiting until the end of the month for their money and got all the wood he needed on credit. By then Bauman and Kessel had arrived and everyone got paid on time.”

The Keystone Studio sign went up on the rather dilapidated former store within a few days. Once the new buildings were ready, it was hoisted to the top of the biggest structure.

“Mack strutted around like a peacock on the road in front of the store,” Normand told Film Weekly in 1929. “He waved at everyone who passed, yelling out to passing streetcars that this was his studio.”

Sennett issued instructions to everyone in the studio that there were certain taboos that must never be broken by any director, actor, or writer. “We will never make sport of religion, politics, race, or mothers,” he said. “A mother must never get hit by a custard pie. Her daughter, yes, as often as possible. Mothers-in-law are fair game, but mothers, never.”

“I don’t believe anyone at Keystone ever broke those rules,” he said in 1959. “My own mother had come out to California to join me, and I wouldn’t have embarrassed her for any amount of money. She used to object, at first, to the girls we dumped in swimming pools. Their wet, clinging, rather revealing clothes used to upset her, but when Mabel Normand, who she adored, told her it was alright, it was alright!”

Once the basic Keystone buildings were in place, Sennett built his own office in a tower on top of the biggest structure. “I could see what was going on in every corner of the studio. I used a megaphone to move anyone I saw sitting around doing nothing into some action or other.” Presumably that is why Indians in full dress and warpaint can be seen as background extras in scenes supposedly taken in downtown Los Angeles.

By the time the studio was functioning, the Sennett-Normand romance was in full swing. Charlie Chaplin said, in 1958, that “one morning Sennett was in a wonderful mood and we knew the romance was functioning as romances should. Other mornings he would stomp around the studio scowling at everyone. Mabel would arrive late, also in a black mood, and we knew they had been fighting.

“At the beginning of 1913 everyone in the studio was part of a gambling syndicate that tried to estimate the day and month when Mack and Mabel would get married. I, and Slim Summerville, the actor, were the only ones who said they would never get married. Long after I had left Keystone I had a visit from one of the studio technicians. He gave me a wad of money and said they’d decided to wind up the pool. Summerville and I shared the kitty.

“Months later I bumped into Sennett and he jokingly asked why I had bet he would never marry Normand. Equally jokingly, I replied, ‘Because we think you are queer [homosexual], Mack.’ He went as white as a sheet and looked down at the ground. ‘How did you know, Charlie, how did you know?’ He dashed away and left me wondering. I recall Ford Sterling once said, ‘How come none of Mack’s girlfriends get pregnant, like ours do? Maybe the chasing is all show and he is trying to fool us.’ And I have wondered from that day on!”

Sennett and Mabel Normand spotted Chaplin a week before they left New York for California in 1912. “We decided to wait until we were settled in Los Angeles before hiring him,” said Sennett in 1943. “When we were ready to put him under contract we couldn’t find him.”

It took Adam Kessel a month to locate him, playing in a small vaudeville theatre in Altoona, Pennsylvania. “Kessel wasn’t at all enthused by the idea of signing this unknown to a year’s contract. ‘Frankly, Mack,’ he wrote me, ‘I don’t think he has any talent at all.’ But I insisted, so Kessel bought him a ticket on the train to Los Angeles. His contract was for $125 a week, a lot of money, but you see I believed he would be a big name, and eventually he was.”

Chaplin never reached his full potential at Keystone. “I didn’t create the tramp costume until I’d been there a month or two,” he said. “Sennett often claimed he devised it, but the basic costume was similar to one an old actor, Fred Kitchen, had used in our Fred Karno stage show. I got his permission to copy it. The moustache was the idea of director Del Lord. The big shoes also came from Fred Kitchen. Long after the “little old tramp” became famous I paid Kitchen an annual sum of money for the rights, and I wouldn’t have done that if Sennett created the costume.”

The Keystone Kops had not been created when Chaplin arrived at the studio, but Sennett claimed to have put him in a Kops uniform on his first day at Keystone. “But he just didn’t seem to fit in with the rough-and-tumble of the Kops, so we never used him a second time.”

Chaplin tells a different story in his autobiography. “I was never, at any time, in a Keystone Kops outfit or film. I was there in 1912 and the Kops didn’t exist until 1913. Their first film was called The Bangville Police. I remember it being made, because I didn’t find it very funny. How wrong I was!

“By that time I was nearing the end of my one-year contract with Sennett and had developed my own tramp character which used subtlety, not slapstick. I can never say I was anything other than bored with slapstick.”

In 1913 Mack Sennett repaid his debt to Marie Dressler. “Few females had achieved fame in comedy by 1913,” he recalled. “So when I told Bauman and Kessel that I wanted to make a six-reel film of Dressler’s Broadway hit Tillie’s Nightmare, using her as the star, they pointed out that such a venture would cost around $200,000 and that Dressler would want at least $10,000 a week. ‘I doubt,’ said Kessel, ‘if Miss Dressler would be interested in making a film even if we paid her that much.’ I casually mentioned that I was acquainted with the great actress and felt I could convince her to come to California.

“I talked to Dressler on the long-distance phone and was getting nowhere until I mentioned that I owed my entire career to her. ‘You do?’ she asked. ‘I don’t recall you appearing in any of my plays.’ I reminded her of the episode in Northampton and she roared with laughter. ‘I often wondered where you ended up,’ she said. ‘So what do you want me to do?’

“Ten minutes later I had convinced her that we had a film version of Tillie’s Nightmare that we proposed to call Tillie’s Punctured Romance. It was ready for shooting, I told her. ‘If you are ready, Mr. Sennett, so am I,’ said Dressler. But could you afford my price of $2,500 a week? I told her we would pay $3,000 and throw in a first-class ticket from New York to Los Angeles, plus all her hotel expenses and the use of a car and driver while she was here.

“‘How do I know you can afford that sort of money, Mr. Sennett?’ she asked. ‘How did you know, Miss Dressler, that one day I would become famous?’ ‘That’s enough,’ she said. ‘When do you want to start?’ ‘In two weeks,’ I said, knowing that the script I had said was ready hadn’t even been started. ‘Make my reservations,’ she said. ‘I shall be at your disposal for four weeks.’”

Sennett worked through the night, sleeping only briefly, for almost a week. “Then I knew I had a great story. I decided to give her the greatest film cast yet assembled. Dressler was to have top billing. I used every big name on the lot: Chaplin, Normand, Mack Swain, Chester Conklin, Minta Durfee, Edgar Kennedy, Charlie Chase, Alice Davenport, Wallace MacDonald, and the entire battalion of Keystone Kops. What a cast!”

Tillie’s Punctured Romance took three weeks and four days to film. It cost, according to Sennett, $180,000 to make. “It was a huge success and made us more than half-a-million, and it launched Marie Dressler on a film career that only ended with her untimely death in 1934. She was the most cooperative star I ever worked with,” he said.

There are many different stories of Gloria Swanson’s arrival at Keystone. The most popular is that Sennett was enchanted by her beauty and immediately signed her to a six-month contract. Others suggest that he wasn’t impressed with her at all but decided her husband, who had already made a few films at other studios, had great potential.

The husband was Wallace Beery. Copies of their wedding certificate have been printed with many stories over the years, but in her autobiography Swanson talks extensively of her Keystone days, but makes no mention of the presence of Beery or that she was his wife.

Sennett’s own version of their arrival on the lot seeking work is probably, for once, the truth. “Immediately Wally Beery walked into my office I recognized him as the man who had given me his second pair of shoes in New York fifteen years earlier. I didn’t remind him, but gave him a contract at the studio immediately. He seemed surprised at the speed in which I made up my mind and suggested I might also like to engage his wife, as they often worked together. I took one look at Swanson and was stunned by her beauty. I signed her, too. Beery never did find out I was the actor with ‘Massachusetts shoes’ in New York.”

Sennett denied vehemently printed reports that Swanson was ever one of his Bathing Beauties. “The story got around because I asked her to pose in a bathing suit with the girls to promote the third film she made with us. She agreed, providing it was only a one-shot deal to help sell this one particular film. And that is a fact, she never was a Sennett Bathing Beauty.”

Apart from the final few films Chaplin made before he left in 1913 for the Essanay Studio at a salary of $2,000 a week, Sennett’s first non-slapstick features were those made by Gloria Swanson. “She was just too dignified to use in slapstick, so we tried a few light romantic comedies. Universal had been making them for at least a year and they were very profitable. Of course, Swanson was a gigantic hit and the films made a great deal of money. By this time she had divorced Beery and he had gone on to better things with some other studio.”

Keystone Studio was, by now, turning out four or five two-reel films every week. Sennett’s contract actors included Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle, soon to be disgraced in a sordid sex trial that cost the life of young actress Virginia Rappe, and his wife Minta Durfee. Others included Louise Fazenda, Mae Busch, and Buster Keaton. Charlie Chaplin’s brother Sydney, who never achieved fame and later became Charlie’s business manager and is credited with making him a multi-millionaire, also worked for Keystone.

Sennett commented on Sydney Chaplin in 1959. “He was useless as a comic, had none of Charlie’s talents, but if only I could have realized his abilities as a business manager I would own this apartment block I live in, instead of renting this one-room shack.”

After Arbuckle was exiled from Hollywood, all his unreleased films were destroyed since no one would show them. His wife, Minta Durfee, stayed on at Keystone. Later, when her acting career was over, she greeted customers daily at a small store she ran in Hollywood for many years until her death in 1975.

At the end of 1917, Sennett decided to sever all connections with Keystone. He, Kessel, and Bauman came to an agreement by which they retained the name Keystone and Sennett was given the right to select forty of the company’s best films of which he would be the sole owner. Most important to Sennett was the fact that he would have ownership of the Keystone Studio. “I had the Keystone name down in twenty-four hours,” he said. “Within another twenty-four hours I had my own sign, ‘Mack Sennett Comedies,’ high in the sky.”

In 1917 Sennett was probably one of the wealthiest men in California. “My accountant told me I was worth about $12 million,” he said in 1943. “I owned two hotels, a movie theatre, and two studios. Keystone was making a million dollars a year profit with all taxes paid. It was time to move on.”

Sennett took the contracts of only a few of the Keystone directors and stars he felt would fit in with the new style of productions he had agreed with Paramount to produce. Paramount, in turn, agreed to give all Sennett productions maximum distribution under their banner.

The Sennett-Normand romance was on one day and off the next. After one serious battle between the two, in 1918, when bottles and knives were thrown around in Normand’s home, she arrived at the studio the next day with a black eye. Sennett announced he was setting up a completely independent company for her, to be called the Mabel Normand Picture Company. He paid all the costs of building a completely new studio for her films alone. Sennett told friends he would have “lost her love” if he hadn’t given her the freedom to choose her own scripts and co-stars.

The venture was initially successful. Normand’s achievements under the Sennett banner had made her into one of the most popular actresses in the country. Fan mail came in from all over the world, and four secretaries were kept busy ten hours a day answering the queries and mailing out photographs. “Of course, she couldn’t sign every one of those photographs herself, so we hired an ex-con, a forger, to do nothing else but sign her name. That worked well until he began to work overtime forging Mabel’s name and my name on company cheques he had stolen.” One of the photographs, dated 1917, quite likely signed by the forger, was recently sold to a collector in London, England, for more than $5,000.

In 1919 Sennett and Normand came very close to marriage. Del Lord recalled the occasion in 1960. “We had all been invited. The party was set for 500 guests. The wedding was to take place at her studio. At ten in the morning, with the wedding scheduled to take place at noon, everyone was told the ceremony was cancelled. Sennett and Normand were nowhere to be seen. I asked him the following Monday what had gone wrong, and he simply answered, ‘You know Del, I really can’t imagine myself being married to a woman.’”

The artistic freedom given to Normand let to a deterioration in film quality. Before they knew it, her studio was in debt. Sennett, determined not to lose Normand, found a script he felt ideal for her. He invested $500,000 of his own money in Molly O, a film which took almost a year to make, an almost unheard of time when most films were still being made in less than a week.

Then tragedy struck. On the night of February 1, 1922, film director William Desmond Taylor was shot and killed in his home at 404 South Alvarado Street, one of the area’s better residential districts.

Mabel Normand was one of the chief suspects from the start. It was quickly suggested that she had been having an affair with Taylor, and she admitted, when questioned, that she had been at his home early in the evening of the night he was killed. Others implicated were the seventeen-year-old actress Mary Miles Minter, whose nightdress was found in Taylor’s bedroom. A hand-embroidered handkerchief bearing her name was on the floor of the murder room.

Sennett, who was interviewed by police along with other Taylor acquaintances, said he first heard of the incident early in the morning of Friday, February 2. “I read the story in the newspapers,” he said. He was asked no further questions.

Sennett told many interviewers that had it not been for the half million dollars he had invested in Normand’s film, Molly O, he probably would never have been declared bankrupt. His biggest worry after Taylor’s death, or so he claimed two decades after the murder, was not who was guilty but of the $500,000 he had spent on the unreleased film. “I remembered what had happened after the Fatty Arbuckle scandal and all I could think of was the half million dollars I would lose. Naturally I was concerned for Mabel, but I didn’t have the same strong feelings for her then.”

Douglas MacLean, a well-known film comedy actor, who lived with his wife next door to the Taylor home, told police he went to the window immediately after hearing what he thought was a gunshot. He said that Davis, Normand’s chauffeur, and her car, which he had seen at the Taylor house about seven o’clock, had gone when he looked out. “It would have been impossible for someone to leave the house following the shots, get into the car, and drive away before I looked from my window,” he said.

Although Taylor’s pocket watch, presumed to have been struck by the bullet, had stopped at exactly 7:21 p.m., MacLean claimed the gun shots were much later, probably shortly after eight, suggesting the 7:21 time was set by the killer to mislead the investigators. “I glanced at my watch as I turned away from the window,” he told the police. “It was several minutes after eight.”

Convinced that what he had heard was a car backfiring, MacLean said he thought no more of the incident until next morning when the police arrived at Taylor’s house. MacLean’s wife, Faith, told police investigators that she saw a rough looking man leaving Taylor’s home at about nine o’clock. “He had a cloth cap down over his eyes and a scarf that seemed to cover part of his lower face,” she said. “I wondered why he needed to be so muffled up because it was not a cold evening. It was quite dark and I only saw his outline.”

Edna Purviance, Charlie Chaplin’s leading lady, who lived two doors further down the road, confirmed Mrs. MacLean’s story. “I, too, saw this rough man,” she said. “I can’t be sure of the time, but think it was a little later than Faith said. It was quite dark and impossible for me to recognize the man. If I must describe him I will say he looked like my idea of a motion picture burglar.”

The investigation dragged on and finally reached the coroner’s court. The names of Mabel Normand, Mary Miles Minter, and Minter’s mother, who had openly said she disapproved of her daughter’s relationship with a forty-five year old man, were bandied about in a manner that suggested the police were convinced one of them was guilty of the crime.

Normand’s chauffeur testified that he and Mabel had left the Taylor home at about 7:15. “I saw Henry Peavey, Desmond’s servant, leave just after seven, a few minutes before we left,” said Davis. “He spoke to me as he passed the car. Apart from him I saw no person other than Miss Normand enter or leave the house.” Questioned about gunshots, he denied hearing any. “And I don’t see how I could have failed to hear them had they occurred while I was waiting for Miss Normand.”

Davis claimed that Taylor came out to the car with Normand, kissed her on the cheek, waved, and returned to his house. “Then I drove her home, where she dismissed me for the night,” he said. “I was home with my wife before eight-thirty.”

This evidence should have cleared Normand, but other evidence suggesting that she had been Taylor’s lover destroyed her career. The film, Molly O, was shelved indefinitely. When it was finally released, several years later, it was a big success. But by that time all rights to the film had passed from Sennett’s hands.

Normand’s career went steadily downhill. She was reported a year later to have been involved in a rather odd shooting incident at her home. A revolver bullet injured one of her guests, but he told police it was an accident and nobody was to blame. The matter was dropped despite the fact that neighbours claimed to have heard at least four shots and a lot of screaming.

That same year she was involved in a drug scandal, and newspapers reported she was addicted to cocaine. She died on February 23, 1930, after a long illness said to have been caused by her drug use.

Mary Miles Minter’s career also ground to a halt. Nobody wanted to see her films. Newspaper readers were convinced that she, too, had been one of Taylor’s sleep-in girlfriends. Her squeaky clean image was totally destroyed by the scandal.

Sennett’s agreement with Paramount survived until 1929, but his output declined and with the first sound films being made, they mutually agreed to end the contract. He joined Educational Pictures that same year and announced he would now only be making sound motion pictures. Despite its name, Educational Pictures produced a wide variety of films, few of which could even be remotely called educational.

In November 1933, creditors of Mack Sennett, Inc., asked for the appointment of a receiver to wind up his studio and film production. Mack Sennett was declared bankrupt a few months later.

“He didn’t stop working,” said Del Lord in 1960. “But now he was just an employee of other companies. He turned out a few sound films but it seemed as though the spark had gone. He told me he had ‘exhausted all the possible tricks of the fun factory’ and planned to retire to write screenplays for other directors.”

In 1937 the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences honoured Sennett with a special Oscar. The citation read: “For his lasting contribution to the comedy technique of the screen, the Academy presents this special award to that master of fun, discoverer of stars, the sympathetic, kindly, understanding genius, Mack Sennett.”

Sennett had little to say on this auspicious occasion. Tears were streaming down his face as he said simply, “Thank you. Thank you, everyone.” The audience, consisting of the biggest names in the film industry, rose to its feet and applauded the weeping Sennett for five minutes.

Little was heard of Sennett over the next decade. He attended parties given by the biggest names in Hollywood, entertained friends at his Hollywood Boulevard apartment, but produced no new films. In the early 1950s he dropped out of sight.

In 1959, at an interview with the author, in the presence of Reece Halsey, an old friend who visited the King of Comedy every day, Sennett, after more than a few glasses of Scotch, started crying and said he wanted to get something off his mind before he died. Halsey told him to relax, that he had drunk too much. But Sennett persisted.

“I want you both to know that I killed Bill [William Desmond] Taylor,” he said. “It was me they saw leaving the house. I stayed there for about an hour after I shot him, looking for things that might incriminate Mabel. I found some letters she had written but I daren’t tell her I had them. I was at the end of the road about seven thirty when I saw her leave in her car, then I went down to the Taylor house. I got my cap and scarf from the studio wardrobe. I kept them on all the time until I got on the streetcar, then shoved them under the seat when no one was looking. The driver looked at me when I climbed on board and I’ve often wondered why, after Faith MacLean and Edna Purviance spoke up, he didn’t come forward to say I’d been on his streetcar. But he couldn’t have identified me; I kept my head down. I got off where I had left my car and drove home.”

Reece asked him why he had killed Taylor, Sennett opened his eyes wide and said clearly, “Because he was a bloody queer [homosexual] and stole Mabel by giving her drugs,” he said. Then he closed his eyes and fell asleep. When he woke up he claimed to have no memory of what he had said. “I know nothing about the murder,” he said. “Absolutely nothing.”

In the latter days of his life, Sennett had elaborated on many stories to make them more glamorous and interesting to the few people he could get to listen. Was this just one more of his fairy tales? Reece Halsey thought so. And there the matter ended. “He has never said anything like this before,” he said. “Mack has always had a vivid imagination.”

Marshall (Mickey) Neilan, a long-time resident of the Motion Picture Home, said before his death in 1958 that he often discussed the Taylor murder with Sennett because he had believed for a long time that Sennett might have committed the crime. “I hated Taylor for what he did to me and dozens, maybe hundreds of others, while pretending to head the industry drive against drugs. Only once did Sennett look me straight in the eyes, and from what we had been discussing, I knew he was about to confess to the murder. But a visitor came in and distracted Mack and that is the end of the story. Dozens of us believed it was Mack but we all hated Taylor and loved Mack so nobody even hinted this to the investigators. If only I had found the courage to kill Taylor myself I might have spent my final days on earth a much better person.”

In 1957 Sennett had been hospitalized for a prostate operation, but when he recovered he refused to go to the Halsey’s home in Beverly Hills to recuperate. “He demanded to go back to his apartment in Hollywood, so that’s where we took him,” said Halsey.

“He started writing again and tried to interest Jackie Gleason in starring in a film of his novel, Don’t Step On My Dreams,” he said. “But as far as I know he never received a reply from Gleason.”

The one-time King of Comedy lived alone, only venturing out to buy groceries at a nearby market. He drank a lot, slept a lot, and cooked all his own meals. Any spare time, when he was not sketching out ideas for comedy films, he spent feeding the pigeons that were always waiting on his windowsill.

Early in 1960, just after his eightieth birthday, when Reece Halsey realized that Sennett was no longer able to look after himself, he arranged for his transfer to the Motion Picture Country Home in Woodland Hills. He had to be carried to the car, protesting loudly that he didn’t want to leave his home.

Once there, however, he became delighted with his surroundings and the attention he was given. “He found many of his old friends from the silent era were also residents,” said Halsey. “He even arranged showings of some of his silent films for the residents. They curtailed his drinking and his health recovered for a short while.”

Mack Sennett, in his last few months on this earth, had once again become an important person. He was idolized by those who he had helped in the past but who, until he arrived at the Motion Picture Home, had no idea he was still alive.

Until only a few days before he underwent further prostate surgery on November 4, 1960, he was in contact with actress Shirley MacLaine. “He wanted me to play Mabel Normand’s role in a remake of Molly O,” she recalled in 1970. “It was obvious that he would never be well enough to undertake such a task, but I visited him and sent him flowers. It was the least I could do for one of the founders of our industry.”

Sennett didn’t survive the November 4 surgery. He died peacefully in his sleep just before midnight.

Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle’s widow, Minta Durfee, talked to reporters after Sennett’s death. “He kept me on at the studio after the trial destroyed Roscoe’s career. He paid me double my usual salary because he knew we had little money. And, without any fanfare, he paid all the lawyers’ fees for the three trials my husband had to endure.

“Although Roscoe was supposed to be barred from all the studios, Mack brought him in to Keystone and actually let him direct several films behind closed doors. He couldn’t credit him as the director so he said ‘Direction by Will B. Good,’ a most appropriate name. Unfortunately, someone talked and that was the end of his directing career, too.

“Later, when he was releasing films through Paramount, he gave Roscoe a lot of small roles. He had lost a lot of weight through the worry, and few people recognized him. He paid a lot more than the parts deserved, but that was Mack Sennett. He never forgot a friend. It’s a pity so many of his friends so quickly forgot about him.

“He would come into my store in Hollywood and buy some trinket worth about two dollars. Then he would offer me a $50 or $100 bill in payment. He knew well I couldn’t change bills of that size, so he told me he’d get the change next time he was in. But when next time came he claimed he couldn’t remember that I owed him anything and that I must be mistaken.”

Minta Durfee said she visited Sennett in his apartment between 1950 and 1958 at least once a week. When he was moved to the Motion Picture Home in Woodland Hills, quite a distance from Los Angeles, she visited as often as she could. “I didn’t have a car and it was a difficult place to get to, so I just wrote him long letters,” she said. “How this wonderful man could be forgotten by the industry is beyond my understanding.”

The funeral service, at the Church of the Blessed Sacrament in Los Angeles, proved that more than just a few people had not forgotten his contribution to the early days of motion pictures. The church was crowded with stars from both silent and sound eras. Among the pallbearers were his Keystone stars, Chester Conklin, Jack Mulhall, and Tom Kennedy. Del Lord, who had suffered a heart attack some months before Sennett died, climbed out of his wheelchair to place a custard pie on the casket. It was a solemn occasion, but the unexpected gesture brought gales of laughter and applause from those attending the funeral.

Sennett’s last request, made to Reece Halsey at the Motion Picture Home before he went into surgery, was that all his papers, photographs, letters, and contracts be handed over to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

Sennett was buried in Holy Cross Cemetery. For some years the grave had no marker until a Los Angeles newspaper story, stating this fact, created considerable concern in the film community. Many offered to pay for a large monument, but Reece Halsey urged that whatever be placed on the grave be simple. And that is how it is today.