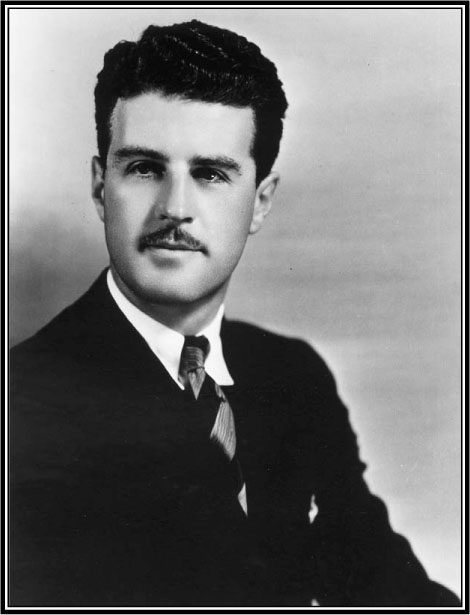

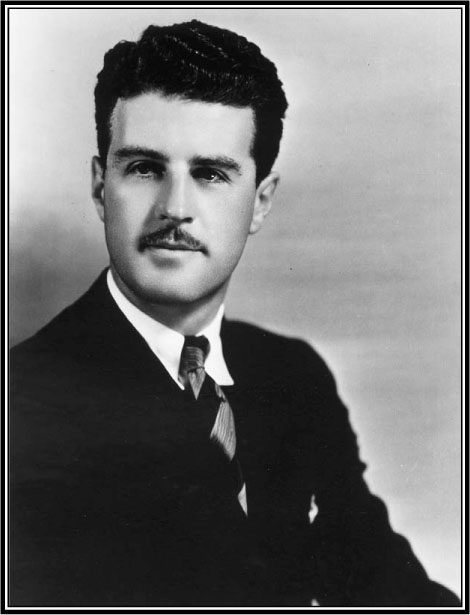

“Douglas Shearer is the only person I know in the world of motion pictures who has received twelve Academy Awards without ever having been seen on the screen. He knew about sound when sound hadn’t been invented. He has made many stars by his achievements in the development of studio and theatre sound equipment. I wonder where I would have been today if it wasn’t for the genius of this man. He is a star himself, but he will never admit it!”

(Spencer Tracy, 1963)

The film industry in Hollywood knew Douglas Shearer as a quiet man who shunned the nightlife of the community, and only rarely could be found at any of the many house parties that were the life-blood of the film industry in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. He was never known to raise his voice, no matter what the provocation. And no one, in the forty-one years he was employed by Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, could ever remember him being angry about anything.

But there was nothing quiet about his remarkable achievements. He was, and is, seventy years after the arrival of sound, still considered to have been the greatest soundman the motion picture industry has ever known. He was piping synchronized sound into theatres in California two years before Warner Brothers were said, in 1927, to have created “talking pictures” when they released The Jazz Singer.

A year before he retired, in 1968, Shearer was asked by a reporter for the Los Angeles Times if he was concerned that Warners got all the credit for “talking films” when MGM had actually been showing a sound movie for six months before The Jazz Singer was shown. “No,” he said. “I knew what the studio and I had achieved, and that was all that really mattered. I was working for the best studio in the world, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, so why should I be concerned about the claims of an upstart studio like Warners?”

Douglas Shearer was born in Westmount, Montreal, Quebec, in 1899. His grandparents came across the Atlantic to Canada from England. His father, Andrew, was born in England but was only four years old when his parents chose to cross the ocean to the New World in an old-fashioned sailing ship.

He loved to tell and retell a story about the ocean voyage his grandfather, a clergyman, his grandmother, and the four-year-old who grew up to be his father, made to Canada. “My grandparents arrived at the dock in London to board the ship with my father and a milking goat. No one blinked an eye as the quartet boarded the vessel. Probably they thought that men of the church were strange people,” said Shearer. “That the goat was to live in their cabin apparently upset no one.”

But on the eve of Good Friday, the day before the fourteen-day voyage ended, with the Reverend James Shearer scheduled to conduct a special church service for passengers and crew, he was approached by the ship’s captain. “Will it be a very messy service, Reverend?” he asked. “Messy,” said Reverend Shearer, rather puzzled, “why should it be messy?” “When you sacrifice the goat on the altar, will the blood fly very far?” “Sacrifice the goat! Is that what you people thought I’d brought it on board for?” roared Shearer. “Good heavens, captain. I brought it so my young son would be able to have fresh milk every day of the journey. He has a rather weak stomach.”

“Grandfather used to tell us it was the most undignified Good Friday service he had ever conducted. ‘I had a hard job to keep from laughing,’ he said. ‘For a joke I decided to tie the goat to the altar, and no one would sit in the first three rows of the chapel. Obviously, the captain had not been able to advise them of the real reason for the presence of the animal.’”

When Douglas Shearer was growing up, his parents lived in a beautiful home on a road his grandfather built himself and named Shearer Lane in Westmount, Montreal. It is still there today, much wider and longer, renamed Shearer Street, befitting its new importance. His father, who was the owner of a building and contracting company, built many of the houses there. A lumberyard he owned at the end of Shearer Street, where it joins St. Patrick Street, was later sold to the Northern Electric Company, still stands on the same site today.

When he was only in his teens, Shearer first became interested in what he described to his sister, Norma, as “the seemingly unlimited miracles of sound and light.” His father was a member of a syndicate that built one of the first power-generating plants in the Province of Quebec. Electricity was soon a very important thing in his life.

While attending Rosslyn School in Westmount, he used to run over to the power plant at the end of each school day to learn the secrets of electricity from plant engineers. His father provided him with a special room in the basement of the family home so he could experiment with the variety of electrical gadgets he continued to create.

An early success, or failure, depending on where you lived, was the building of a set of telegraph wires that ran across neighbouring properties and ended in the basement of a house almost half a mile away, where an equally enthusiastic young friend and experimenter lived. He hooked the wires up to the electrical system in his home and sent messages to his friend. Unfortunately, more than once he knocked out all the power circuits in an area covering several blocks around his house. Fortunately for young Douglas Shearer, no one but his father ever found out the cause of the blackouts.

After the fifth blackout, Shearer, Sr., bought Shearer, Jr., a camera. The younger Shearer soon became fascinated with light and lenses, and in 1915 had set up his own basement photographic studio and was producing some remarkable pictures of his pet dog and those of the neighbouring children who could be persuaded to pose. Unfortunately, all these achievements didn’t make him too popular at home since he invented his own evil-smelling chemicals to develop and print the photographs.

Reminiscing many years later, he recalled that the house “often smelled like rotten eggs. My father told me years later that some of his friends stopped coming to the house because the smell was almost overpowering. I can see why it might have been a little embarrassing, and why they finally built me a little hut in the garden where I could experiment alone.”

Shearer dropped out of high school half way through his graduating year. “I got the highest possible marks for mathematics,” he said, “as that was the only subject I could imagine would help me become an electrical engineer. In those days it wasn’t hard for a fourteen-year-old to get work, especially if, like me, you were prepared to do all the dirty jobs to learn a trade.”

Supervisors at the Northern Electric Company plant in Montreal were the first to realize that Shearer was not just a run-of-the-mill employee. Soon he was upgraded to experimental work in the use of electricity for carrying signals over long distances.

At eighteen he entered McGill University to study physics and engineering. “How did a high school dropout get into such a prestigious university?” asked a newspaper reporter in 1930 after he had just received his first Academy Award. “By persuading my old headmaster that I deserved a second chance,” he said. “He gave me a phony graduation certificate that could have got me elected prime minister of Canada.”

At McGill University Shearer joined the Officers’ Training Corps. World War One was raging in Europe and he hoped the things he learned would bring him an offer from the British Royal Flying Corps. But in 1918 his world came crashing down. “I had been accepted by the Royal Flying Corps, forerunner of the Royal Air Force, when probably the greatest flu epidemic of all time hit Montreal. I was one of its first victims. I was ill for nearly six months and when I was fit enough to rejoin the corps the war was over and they didn’t need any more Canadians. Which is perhaps just as well, for war records show that the average life span of a pilot in those days was less than one month.”

Plans to return to McGill University in September 1918 were halted when he discovered there was no money to pay his fees. “My father had suffered a number of major financial setbacks so, at nineteen, I had to go to work to provide some additional money for the family.” The Shearer family, at that time, consisted of his father and mother, himself, and two sisters, Norma, born in 1902, and Athole, born in 1903.

“I spent about two years in a machine shop, and the luckiest break in my life came when the company took on, as an experiment, a line of industrial power plant equipment. I learned very quickly all I needed to know about the principles of mechanics. Often I was sent out to talk to the top mechanical engineers of Canada working in a variety of industries from coast-to-coast. They became my teachers. I asked lots of questions and they were more than willing to answer and explain the mysteries of the many new discoveries that had arrived through wartime research. I doubt if I could ever have got this vast work experience if I had been able to return to McGill. That is why, at MGM, I have always preferred to hire young people with a smattering of knowledge, but willing to learn, rather than older more experienced technicians who have become set in their ways and feel they knew everything there is to know!”

In 1920 Shearer added a sideline to his now lucrative engineering work. “A friend was planning to buy a Ford dealership but was afraid to go ahead until he was sure he had the right man to handle the mechanical work in the dealership repair shop. ‘How about me?’ I asked. ‘Fords don’t break down often. I could do it in my spare time.’ He was delighted to think he would get a qualified engineer at part-time rates, so we went into business. I got no salary, but twenty-five percent of the profits.”

That same year his sister, Norma, then nineteen, convinced her mother, Edith, that she, Norma, and Athole should move to New York to further the singing, acting, and modelling career she had successfully started in Montreal, like Douglas, to earn money for the family.

“I went down by train to New York a couple of times in 1921 to see her work,” he said. “Father had decided to join them. We sold the house and I moved into an apartment. In New York I watched the photographers, where Norma was modelling, struggling to get good results with inadequate lighting. But when I suggested a few ideas from my own photography experience, I was gently ejected from the studio.”

It was a different story at the Biograph Studio, where Norma got a few small roles. Shearer found directors much more willing to listen to his ideas. “They actually offered me a contract to design a new lighting system for the studio,” he said, “but I had commitments in Montreal so reluctantly had to say ‘no.’”

He had been back in Montreal for two weeks when an unexpected letter arrived from Florenz Ziegfeld inviting him to New York “to explore the possibilities of making lighting more exciting for the Ziegfeld Follies.”

“Apparently a day electrician at Biograph, who worked nights in Ziegfeld’s Broadway theatre, told him some of the things I had suggested at the studio. I liked the idea of going back to New York, especially since it meant I would be reunited with my family, but I just couldn’t see myself letting my partner in the Ford dealership down. I am not too shy to say there were few engineers as good as I was at that time in Montreal. The dealership flourished as people got to know that cars from our salesroom were always in tip-top shape before they were sold, and if any problem did develop we fixed it expertly and promptly.”

By 1922 Norma was becoming well known in the many small film studios that had sprung up in New Jersey and New York City. “Irving Thalberg, working as a production assistant at Universal Studio in Hollywood, saw some of her work and was impressed enough to convince the studio head, Carl Laemmle, to offer her a twelve-month contract in California. When she decided to accept the offer, the whole family decided to move with her. Father thought he might be able to get back in the lumber business down there, and later did, very successfully, providing, often on a minute’s notice, any kind of wooden product the studios needed for sets.

“Athole got a few small roles in films at the Biograph studio in New York, but had no real ambition to become an actress. But when Mr. Laemmle offered her a position in his script department in California she jumped at the chance.”

Two years later, the Ford dealership owner decided to sell the franchise. “He had a very large offer and since I would get twenty-five percent of the money he received, I agreed with him that it was too good a chance to miss. I had long since left the machine tool company as the Ford job rapidly became a full-time operation. I had quite a lot of money in the bank so decided to visit California to see my family again.”

Shearer bought a return rail ticket, first class, packed his special belongings, sold his furniture, and gave up the lease on his apartment. “Why a return ticket, you may ask?” he said. “Well, I wasn’t really sure I wanted to leave Canada for good and with the ticket in my pocket I knew I could go home any time I wanted.”

Six months later he tucked the return half of his rail ticket deep down in the bottom of a box of souvenirs and decided to forget about returning to Montreal. “By that time Norma had moved over to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios. Irving Thalberg, who had first realized her potential when he was at Universal, told Louis Mayer, when he was invited to join MGM as a producer, that he would accept if the studio put Norma Shearer under long-term contract as an actress.”

At a party given by Thalberg in his home, Shearer met Jack Warner, head of Warner Brothers Studio. “All the studio heads were friendly in those days,” he recalled. “Warner asked if I planned to stay in California and I said ‘yes’ if I could find a job. He told me that in his studio everyone started at the bottom, and if I really wanted to learn the film industry I could have a job in the studio prop room. I accepted on the spot and started work the next day.”

For more than six months, Shearer moved props on and off the many sets at Warners. “I saw Jack Warner quite often, but any attempt to talk him into giving me a better job was fluffed off. ‘You need much more experience,’ he said. ‘In a year or two we’ll talk.’”

Any spare time he had, Shearer spent at MGM where Thalberg encouraged him to learn techniques that might improve the rather primitive cameras still in use in the industry. “In those days there were no unions and MGM, in particular, used to work from six in the morning and end sometimes as late as midnight, so I had lots of time to dabble in electrical and camera things at MGM.

“Something I have never forgotten, and have used as a guide throughout my career, was the example set by Louis Mayer. If the first set was opened at six, he was there. If the last lights were shut off at midnight, he was there. A lot of people don’t like him, but that is usually jealousy because of his success. It should be made clear that everyone who works for him respects him. He never asks anyone to do anything he wouldn’t do himself.”

In July 1925 Thalberg spoke the magic words Shearer had been waiting to hear. “We need you here at MGM,” he said. “Some of the things you have been doing are remarkable. I have talked with Mr. Mayer and you can start whenever you like. Your job will be to experiment with lighting, film, cameras, anything you want to do.”

“And sound?” asked Shearer. “That’s a long way off, if it ever comes,” said Thalberg. “But, yes, sound if you wish.”

Shearer’s first MGM contract was for one year at $150 a week. “Three times what Warner had been giving me,” he said, “so I marched in his office and asked when I could leave.”

“Today, if you wish,” said Warner. “I only gave you a job to keep you happy. If someone else in the industry thinks you have more talent than you have shown working in the prop room, I wish them well with you.”

Warner rose, shook hands with Shearer, and signalled that the interview was over. Louis B. Mayer later said, “That was just one of the many mistakes Warner made. He couldn’t see talent even when it was right under his nose. Thalberg and I had been watching Shearer from day one, and we knew he was going to be a force to be reckoned with in the industry.”

Within six months Douglas Shearer’s name was on everyone’s lips in the industry. During the filming of Slave of Fashion, which starred his sister Norma, he approached Thalberg with a startling proposal. “I know we can’t make the entire film talk,” he said, “but let’s make a talking two-minute trailer that goes to the theatres the week before the film is shown.”

Many years after the moment he surprised Thalberg with his proposal, Shearer laughed about the producer’s shock when he heard the idea. “He was literally stunned,” he said. “When he recovered he said, ‘Are you really still talking about sound Douglas? How can we possibly make the trailer speak. No, I don’t want to hear about it, the idea is too ridiculous.’ He walked away, about ten feet, then he turned and walked back to me. ‘Can you really do it, Douglas?’ he asked.”

Knowing that his career could possibly be on the line from his answer, Shearer replied, “Yes, Irving, I can.”

Thalberg clapped him on the back and said, “Then do it, Douglas, do it!” Shearer discovered later that the usually unflappable Thalberg ran over to Mayer’s office and gave him the news. Mayer, whose greatest asset was his ability to make instant decisions, looked at Thalberg and smiled. “Then why are you wasting time over here when you should be working on the project,” he said. He indicated the discussion was over by dismissing Thalberg with a wave of his hand before turning away to talk to Ida Koverman, his secretary.

Shearer’s revolutionary idea was to add sound, both music and dialogue, to the Slave of Fashion trailer at each of the fifteen theatres where the film was to be presented the following week.

“The most important thing in the success of this idea was for the actors to speak their lines clearly during filming so the camera picked up every movement of their lips,” recalled Shearer. “When the pieces of the film to be used in the trailer were chosen, spliced, and edited, we stood the actors in a line, with their scripts, and they “dubbed” the words they were saying silently on the screen, as we do today with foreign language films. We recorded the dialogue on a regular record machine, and when we played it back synchronized with the trailer the result was quite startling.

“When Mayer saw the film he stopped work on every set and invited everyone to see what we had created. He warned the whole group that if they mentioned what they had seen they would be fired. There was great applause, and we felt as though we had cleared a major hurdle toward the creation of talking pictures.”

The initial recording was only the first step for Shearer. “I knew we needed more than just the dialogue so, with Mayer’s blessing, I had a studio arranger compose music to complement the two minutes of film. We added a music leader of ten seconds so the projectionist would have ample warning when to start his machine. Thirty musicians recorded the sound on a separate disc while the conductor watched the film on the screen so the music would be loud for the opening and ending, but subdued during the spoken dialogue. Remember, we hadn’t at that time discovered how to combine the dialogue and music on one disc.”

Douglas Shearer

Originally, it was Shearer’s intention to make fifteen copies of each sound recording and ship them, with two record players, to each theatre. “This worried us quite a bit,” he recalled. “We would need thirty reliable people able to synchronize the sound with the film, and we just didn’t have those people. We weren’t concerned about the projectionists, because the ten seconds lead music gave them a cue when to roll the film.”

For a while it was decided that the sound venture would only be risked at one of the fifteen theatres.

“Then I had an idea,” said Shearer. “I asked Irving Thalberg to give me one more day to come up with a solution. I drove to downtown Los Angeles and talked to the manager of one of the two radio stations then broadcasting in the area.

“I proposed that they should have the recorded sound and music in their studio and at a predetermined time they would put both discs, synchronized, on the air. We would provide each of the theatres with the best quality radio receivers available and I devised speakers, rather like the old megaphones the band singers used, to increase the volume of the reception.

“The radio station’s owners were enthusiastic about the idea, and agreed they would do it if MGM would invest quite a few thousand dollars they badly needed to buy new equipment for their studio. Mayer gave the OK and we started making plans and setting a date. We tried it out at one of the theatres in the middle of the night when there was no audience and the radio station wasn’t supposed to be broadcasting, and it worked beautifully.”

Mayer, Thalberg, Norma, and most of the studio heads went to one of the fifteen theatres and sat quietly at the back awaiting what they hoped would not be too much of a shock for the audience. “Well, it worked beautifully in all fifteen theatres,” recalled Shearer. “It was so successful that audiences stood and cheered and asked for it to be repeated. I had to telephone the radio station and set a time for a replay. They held us to ransom for a lot more money but Mayer agreed it was worth the expenditure. I have never seen so many excited people.”

The theatre owners demanded that MGM repeat the sound effects every night for the rest of the week. “Once again I had to negotiate with the radio station and MGM paid over another fistful of dollars,” said Shearer. “Theatre managers called to tell us their theatres were packed every night of the week. A sample survey we made suggested many were people who had heard the ‘sound miracle’ once and went to hear it again and again.

“Everyone at MGM was stimulated and ecstatic with the result of the experiment. But the big letdown came the following week when Slave of Fashion was shown in its entirety. Unfortunately we had obviously not made it clear that only the trailer would have sound. Patrons started booing when the complete film was as silent as all the others they had seen until that time were. We had to take the film off after the Monday showing. It was a good film but we had to shelve it for awhile, only releasing it months later, with a silent trailer, to other theatres across the United States.”

Two years later, there was a sequel. MGM became the owner of a radio station in Los Angeles. The original owners had declared bankruptcy, and the courts decided that MGM, with its sizeable financial involvement, was the legal owner and must pay all the bills. The studio owned the broadcasting station for twelve years before selling it for a large profit to one of the national radio networks.

By 1926 sound was obviously going to be the big thing in the motion picture industry. Warner Brothers mortgaged their studio and joined forces with Western Electric, soon to become the elite of the sound world in American theatres, to win the race.

But the newsreel companies beat them all. Early in 1927 a Fox Movietone News film was shown in New York to a startled audience who heard people like Calvin Coolidge, Babe Ruth, and Charles Lindbergh speak to them from the screen. The Fox studio equipped about 100 theatres with equipment designed to amplify the voices and music of its newsreels.

The Warner and Fox methods of sound were to use disc recordings separate from the film, as MGM had with its radio and theatre experiment. Warner’s experiment with more than 100 Vitaphone short subject films was, at times, far from successful. If the film broke and had to be spliced, there was no way to change the sound on disc and often the pictures and voice were a long way from being synchronized.

Although it is always called the first talking film, Warner Brothers’ The Jazz Singer was not true sound on film; most of the film was silent with only a musical background, but at the end Al Jolson startled his audience by facing them and providing a brief vocal interlude.

Meanwhile, Douglas Shearer was busy at MGM. Thalberg, in his memoirs, talks about a meeting between himself, Mayer, and Eddie Mannix, the latter sent in by the New York head office of Loew’s Inc., owners of MGM, to be comptroller in Los Angeles. “Mannix asked Mayer what he was doing about sound film production,” he said. “Mayer looked flustered for a second and said, ‘Eddie, we’re ahead of everyone, we have the most advanced and informed sound man working for us. He has been here two years now and you can take my word for it that we will be first when the real sound on film is created.’ Mannix congratulated Mayer and left the room, no doubt to advise New York that everything was under control. I turned to Mayer and asked who this genius was. ‘You brought him here, you should know,’ said Mayer. ‘Young Shearer, that’s who I mean. Let’s give him a title, and double his salary before Mannix asks too many questions. Tell him I say he has freedom to experiment with sound any way he wishes and to hire a staff if he needs them. What shall we call him?’”

After some discussion, Douglas Shearer was called to Mayer’s office and advised, first that his salary had been increased to $300 a week, and second that he now had an official title, Director of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Sound Research Department.

Shearer laughed about this many times. “For almost a year I was the entire sound department. I knew the secret to sound films could only be found by putting the words and music on a strip of magnetic tape that ran with the film, but how to get it to work was the problem. I could find no one else who agreed with me so I hired no one.”

In 1928 Irving Thalberg married Norma Shearer. “You might have imagined I would be greatly enthused over the marriage,” said Shearer, “but it did nothing to help my career. Few of the people at MGM had any idea where my experiments were leading and I’m sure, for a while, most of the studio employees thought of me as someone being shunted off to a dead end job because I was Norma’s brother.”

But Shearer persevered and got permission to hire Professor Verne Knudson, an expert on acoustics employed at the University of California in Los Angeles, to design the new sound stages he knew would soon be needed. The resulting buildings were so solidly built that they have withstood several earthquakes and are still in use today by the Sony Corporation, which took over MGM in 1991. They are now used to house the production sets of many popular TV shows, including “Jeopardy” and “Wheel of Fortune.”

By now Shearer had, with the help of the Victor Recording Company, devised a method of recording sound on film. “Of course,” he said, “the soundtrack was recorded separately on a different film to that in the camera, and later we had to marry the two together to provide the complete picture. This allowed us to edit each separately and finally add a music track to the finished film, a much superior method to that used by other studios.”

When Shearer started work on his sound research there was no method existing to make the transfers of sound to the actual film. “My research department had by now about twenty employees; working in groups of four they tackled different problems that faced us,” he said. “I went from group to group, working with them and suggesting ways that hold-ups could be overcome.”

Little by little, Shearer and his team solved all the problems, and when it came time for MGM’s first complete musical, The Broadway Melody, to be filmed in 1928 for 1929 release, the sound department had the answer to all the difficulties that had faced them.

But Shearer didn’t devote all his time to sound. “I realized that if we were to get quality sound we had a lot of other things to eliminate first,” he said. “The cameras of that time were quite noisy. It hadn’t mattered while producing silent films, but now the primitive microphones picked up the whir and the soundtrack produced something like a cat purring continuously. First we tried putting the camera in a soundproof box, but the cameramen almost suffocated and the cameras soon became dangerously overheated in the closed area. The obvious solution was to build a more silent camera, so I devised that. At first the cameras were placed in one spot and were not movable. It quickly became obvious that this greatly limited photographic possibilities, so I devised a camera dolly that could follow the action.

“Most of the early sound films were just reproductions of stage plays with the camera planted where the audience would have been. There were no opportunities for long-distance shots or close-ups. Then there were the microphones. We tried hiding them in the clothing of the actors, but mikes were big and couldn’t be easily hidden. I produced a small microphone that was used in clothing for awhile but every time the actor moved the rustle of clothing was picked up.”

Shearer finally decided on using a static microphone hanging over the heads of the actors, just out of camera range. “This worked beautifully when the actors were able to stand still, but the sound faded in and out when they had to move. We already had our camera dollies and the obvious solution to record moving actors was a moving microphone, on a boom.

“It sounds so easy now, but at the time we had a hundred difficulties. The camera dolly and mike booms often collided. Shadows of the mike boom were constantly crossing the faces of the actors or could be clearly seen on the wall behind the action.”

At this point, Shearer decided to once again enter the lighting field. “I remembered what I had done in my small Montreal studio to eliminate shadows and convinced Mayer that he should put me in charge of all set lighting. I was fortunate to be associated with Cedric Gibbons, the art director. Before each film we discussed the light and sound difficulties and he came up with innovative set designs that eliminated almost every problem.” The credits “Sound by Douglas Shearer” and “Art Direction by Cedric Gibbons” appeared on hundreds of MGM films until 1960, when Gibbons died.

Louis B. Mayer was one of the founders of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, which annually awards Oscars to those people in the film industry considered to be the best in their own particular field. The first Academy Award for excellence in sound was awarded in 1930. The winner was Douglas Shearer for the soundtrack of The Big House. Jack Warner was so incensed by Shearer’s win, expecting his own studio to take the honours, that on the night of the awards he started a feud with Mayer that lasted, with the exception of one single day in 1943, until Mayer’s death in 1957.

The Big House, which starred Chester Morris, Wallace Beery, and Robert Montgomery, is available for film buffs to see on video. It is remarkable for its clarity of sound and consistency of volume, so often lacking in early sound films.

Shearer told the New York Times after the awards ceremony that few people had any idea of the problems sound recordists faced. “For example,” he said, “it took us a long time trying to discover how to record a simple thing like raindrops. At first they sounded like marbles dropping on a wooden floor. After many tries we came up with the answer. We learned to ‘damp’ the sound by putting several layers of blotting paper on window sills, or placing heavy layers of felt on the ground just out of camera range.”

On June 6, 1931, when Shearer was deep into his studio experiments, tragedy hit his life. His wife, distraught over the death of her mother, killed herself in front of hundreds of horrified spectators on Venice Pier, not far from the Shearer home in Santa Monica.

Venice police reported that Mrs. Shearer had approached one of the shooting galleries on the pier. The attendant told the police that she “played with the pistol for a few seconds before taking two wild shots at the targets, then she put the pistol to her head and fired.” Mrs. Shearer died instantly, said the doctor who was called to the scene.

Shearer testified at the inquest. “We all tried very hard,” he said, “but she was unable to recover from the shock of her mother’s unexpected death in May. One day I found her examining a revolver I kept at home, and I removed it from the house to my office as a precaution against what I feared. I hired a full-time nurse to stay with her at all times when I was not at home, but on June 6 my wife somehow slipped away.”

The Shearers’ next-door neighbour, Mrs. Waldo Waterman, told the inquest that Shearer had asked her, and her husband, to visit Mrs. Shearer as often as possible to keep her mind occupied, “but every conversation we had seemed to turn to her mother’s death and she would start weeping uncontrollably.” A verdict of suicide while of unsound mind was returned.

Immediately after the funeral Shearer returned to his research. “He even had a bed installed in his office,” said Martin Marsh, who worked with him. “He moved some clothes and toiletries in and it wasn’t unusual for him to stay there for several nights on a run.”

On August 20, 1932, just a little over a year after his first wife’s death, Shearer’s friends were surprised to read in the papers a brief announcement from Las Vegas. “Douglas Graham Shearer, 32, motion picture sound technician and brother of Norma Shearer, screen star, was married here today to Ann Lee Cunningham, 28, of Los Angeles. Immediately after the ceremony they left in Shearer’s private airplane to return to Hollywood where they will make their home.”

“He returned to work the next day as though nothing had happened,” said Marsh. “Perhaps he hadn’t realized that the story of his wedding had been printed in the Los Angeles papers, and when we got together to go in and congratulate him, he told us not to make a fuss about it. ‘I was lonely,’ he said. ‘And Ann has turned out to be a perfect companion to alleviate that loneliness.’ And that is all he ever said about the marriage. Only a few of his closest friends ever met his new wife. They kept to themselves and were rarely seen at any of the opening nights or at house parties. I never did meet her.”

In the early 1930s Shearer was named director of technical research at MGM. This position gave him total control over all the studio’s scientific and technical advancement work in film production, from camera to laboratory to projection and sound.

In 1935 he won two more Academy Awards. The first was for sound recording of the Jeanette MacDonald and Nelson Eddy film, Naughty Marietta. Available on videotape, it is a great example of the early work of Douglas Shearer. His other award was for his research and development in perfecting a method of automatic control of film cameras and sound recording machines.

Despite all the advancements with less noisy cameras, improved lighting, and better microphones in the studios, a big problem remained unsolved in the theatres themselves.

“Not only was the sound distorted in the theatres with the primitive amplification of those early days, but seats in certain parts of the theatres were never full. People just wouldn’t sit there because the sound was so loud and harsh. We needed good sound in the theatres just as much as we did in the studio if moviegoers were not to get tired of what was still considered by many to be nothing more than a fad. After all, Charlie Chaplin was still making silent films and packing the theatres with his genius.

“So I spent six months devising a two-horn system of sound reproduction that made it possible for music to come out of one speaker and voices out of another. You might say the concept was a forerunner of stereophonic sound.” The two-horn method was improved by Shearer over the years, and was still the basis of all theatre sound equipment in use forty years later when he died.

This system won him his fourth award at the 1936 Oscar ceremonies. The film about the 1906 earthquake, San Francisco, gave him a second Academy Award for the year; he always considered it his finest work.

“For this film we tried something different that has now become standard practice,” he said in 1943. “The director shot his scenes complete with dialogue. Then he turned over the film to me. We had devised a master film soundtrack that could be divided into eight individual tracks. Track one carried the studio dialogue. Track two the rumble of the earthquake. Track three falling walls. Track four crashing timbers. Track five the crackle of flames. Track six the screams of panic-stricken people. Track seven the sirens of fire engines. Track eight the discord of a piano as it crashed to the ground, and all other background musical effects.”

As the film was run off in the projection booth, Shearer’s creation, the first sound “mixer” used in the film industry, brought in the tracks individually, regulating their volume at a control board at which Shearer sat. “You might say I was a little like a conductor of a symphony orchestra as I blended the different sounds together on one single track,” he said.

When it was released, San Francisco had everyone hanging on to their seats in theatres around the world. At the 1936 awards ceremony, Clark Gable, one of the film’s stars, told the news media that he hadn’t seen the completed film until the premiere night in Hollywood. “It was incredible,” he said. “With only dialogue in the studio it seemed very tame, but with Douglas Shearer’s sound and John Hoffman’s earthquake sequences, it had me gasping for breath with its realism. The people around me were screaming as loud as those on the screen. I probably let out a few yelps myself.”

The year 1937 brought Shearer two more Academy Awards, for technical achievements in advancing the use of sound and for the development of a new camera drive system that guaranteed absolute camera speed accuracy at all times.

In 1940, one of the most enduring musicals of all time, Strike Up the Band, starring Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney, with its complicated musical score, earned him another Oscar.

At the awards banquet of that year he modestly told an interviewer from the Los Angeles Times that he never actually invented anything. “All I did,” he said, “was to take existing principles established by voice-reproduction techniques and use a little of my own skills in adapting these essentials to the new needs of sound reproduction by way of the screen.”

Three years after he made that statement Douglas Shearer, when he reread it, roared with laughter. “I hope he and his readers understood what I was saying. I’m not sure that I did!”

In 1941 he showed his amazing command of all aspects of motion picture production by devising a fine-grain film that provided greater clarity and crispness when magnified many times on the huge screens then being used in the bigger theatres. This put one more Oscar in his trophy case.

Little was heard of Shearer from October 1943 until early 1945. Those enquiring about his absence from the studio were told he was working on a major development for location work, and there was no set date for his return. It was some years before his absence was fully explained.

This was the story he told in 1947. “In September of 1943 I received a visit at the studio from the British ambassador to the United States. He had flown from Washington with a personal letter to me from the British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill. The letter explained that development of radar was a number one priority in the European war, and Mr. Churchill felt that my knowledge of sound and cameras might be useful in solving some of the problems that were plaguing them.

“Of course, I was flattered, but I felt any work of this sort should be done in conjunction with the United States government. I asked the ambassador if I could fly back with him to Washington so we could discuss how both our two governments could become involved.”

The British ambassador was more than willing to utilize the vast research facilities of the United States and a meeting was arranged at the White House with President Franklin Roosevelt and the United States’ military chiefs of staff.

“The rest is easy to explain,” said Shearer. “With the president’s blessing and support I started work at a location that is still top secret and we were able to perfect the radar that I believe helped shorten the war.”

He was offered a civilian award for his military achievements but declined the opportunity to have his work recognized. “I didn’t do it for personal glory,” he told President Roosevelt at a White House dinner he and his wife attended. “I did it to help save lives and get the war over and done with.” But he always kept, in his study with pride, a framed letter from Winston Churchill congratulating him on his work.

In 1947, Variety wrote a short article telling of a visit by Shearer to the Office of Naval Research (ONR) in Washington, where a special tribute was paid to him for his wartime achievements. “Among Shearer’s discoveries,” said an ONR spokesman, “were ways to reduce the complex mathematical computations required in methods developed by such scientists as Einstein and Dr. Robert Millikan, so they could be utilized much easier in a number of naval projects.”

Years later it was also revealed that his radar research had continued at a site close to Los Angeles into the 1950s. Using his radar and sound knowledge, he invented a device that allowed the United States to determine when and where nuclear explosions were taking place anywhere in the world. The principles of his findings are still in use today, probably by every major country in the world. At no time did he receive one cent for his work with the government, or for his discoveries.

Back in Hollywood in 1945, Shearer continued with his experimental work at MGM. Thirty Seconds over Tokyo, showing the first attack by the United States on Japan, starring Spencer Tracy, earned him another Oscar for his sound recording expertise.

Green Dolphin Street in 1947 and The Great Caruso brought him to the podium twice more to receive Oscars for his ever-improving sound methods.

Cinemascope was all the rage in the late 1950s, but audiences soon got tired of seeing the lines down the screen where the images from three projectors overlapped. With Ben Hur being prepared for production at MGM, Shearer concentrated his efforts on finding a way to produce wide-screen films using only one camera.

His invention, known as Camera 65, because of its use of sixty-five millimetre film instead of the standard thirty-five millimetre stock, and the creation of the film it used, brought Douglas Shearer his twelfth and final Academy Award in 1959. He also got rid of the curved screen, characteristic of Cinerama, and showed how Camera 65 could be shown on a flat, but wide, screen. It became known as Panavision. After the ceremonies he told the newsmen present that “thirteen might be an unlucky number, so I won’t try for any more awards. From now on I’ll be in the background letting the creative young minds at MGM take full credit for their achievements.”

In May 1961 he was once more in the news, but not in a way he enjoyed. Papers nationally printed a brief item that said, “Douglas Shearer, winner of many Academy Awards at MGM for his engineering expertise, was today divorced by his wife of twenty-seven years, Ann, fifty-six. ‘He was never at home,’ she said. ‘It was no longer a marriage.’ The court approved an agreed settlement dividing community property valued at $800,000 between them.”

In 1963 his name was on yet another award announced by the Academy. It was given to recognize the engineering work done by MGM in the creation and development of a background projection system that permitted exteriors to be shot indoors, with even studio technicians finding it difficult to tell which was the real outdoors and which was filmed in the studio. As the award was given to Shearer and the entire MGM research department, he declined to attend, saying, “It is time the department as a whole got the credit.”

Accepting the award, a young researcher at MGM said, “Mr. Shearer may not be here in person, but his inspiring presence was felt on many occasions during the development of this system.”

In 1965, when he was sixty-six, he married for a third time. There was only a brief announcement in the Hollywood Reporter that his new wife was named Avice and that the couple would live in Shearer’s Santa Monica home.

Three years later, in 1968, he retired. “I am no longer young,” he said. “At sixty-nine I am slowing down and at times it becomes difficult to get up in the morning and drive to work. The industry is not the same as it was when I first came to Hollywood in the late 1920s. A lot of the fun has gone from making films. There cannot be too many things now left to invent. Or, if there are, I can’t think of them. So what better time for me to retire.”

He was not seen in public again. A few months later, friends calling his home were told by his wife that Shearer was in a convalescent home due to a progressive and terminal illness. He allowed only his wife and two grown sons from his second marriage, Stephen and Mark, to visit him during the two years he remained under medical care.

In January 1971 Douglas Shearer died, leaving a huge legacy of advancements in a wide variety of technical fields associated with the motion picture industry.

He would have been very happy to see the prominence given to his death in the obituaries that were printed in national and trade papers. The New York Times gave his passing fifteen inches of space on its front page, an honour usually only offered to the giants of industry and politics and a few of the more important film actors and actresses.

At seventy-one, Douglas Shearer had earned his place in the sun. Many of his films that won awards, and even more of those that didn’t, are available today on videocassettes. Mark Warner, a film buff in Beaumont, Texas, was reported in a newspaper story printed in 1991 to have collected more than 100 of the feature films in which the credits listed “Sound by Douglas Shearer.” “He was the ultimate sound man,” said Warner. “There will never be another Douglas Shearer.”