Chapter 44

by Karyne Johnson

I grew up in northern California, immersed, ensconced, and inexorably indoctrinated in the Mormon culture that my father, and generations of his family before him, had adopted unquestionably as their chosen faith. It was a doctrine passionately promulgated by zealous missionaries who enticed my great-grandparents from Scotland to America in the late 1800s to begin their lives anew under the tenets of a religion that gave them privileged access to a promised land of plenty, “safe from ridicule and strife,” in a community of like-minded fellow “Saints.” For all intents and purposes, “Saint” should be the operative word here, because even as a little girl growing up in a household hell-bent on adhering to the teachings of its prophets more than a hundred years after my great-grandparents’ conversion, I was fully expected to be a saint. Truth be told, I was anything but. And the promise of living in a place safe from ridicule and strife? That too proved to be a lifelong contradiction for me.

Being a member of the Mormon Church of Jesus Christ of the Latter-day Saints meant conforming to ideals, rules, and regulations that dictated one’s every thought and action. I resisted them for as long as I could remember. I was spirited and outspoken, more apt to challenge authority than acquiesce to it. I was put off by rigid thinking and dreamed of a life full of adventure and creative fulfillment. I longed to be appreciated and accepted for who I was and what I believed in. And perhaps more than anything else, I wanted my father, a pillar of the Church and the patriarch of our family and Mormon community, to be proud of me and not the saint I was expected to be.

My father cut an impressive figure. An MBA graduate of Palo Alto’s cerebral Stanford University, he was sophisticated and refined, highly intelligent, endlessly motivated, and a born leader. He excelled in high school, both academically and socially, parlaying his redheaded good looks and affable personality into easily won elections as class and club president. In spite of his rarely talked about, challenging undergraduate years at college, “Red,” as he was fondly known as by friends and colleagues, went on to serve a distinguished tour of duty in Naval Intelligence and further his education while a newlywed.

The firstborn, I came along when my father was on the fast track to success at school, with dreams of climbing the corporate ladder at AT&T. That he had wanted a son became apparent to me as I grew up in the shadow of his disappointment. Having a son was more than a point of pride for Mormon men like my father. A son meant that their legacy of leadership would be passed on for eternity. Daughters could never hold that priesthood position in the Church, could never attain the status and power that separated them from the laypeople in their congregations. Daughters could not become the “gods” the men aspired to be. So I never could be good enough or smart enough to live up to his expectations no matter how hard I tried. He may have faulted me for being a girl, but he couldn’t deny that I was persistent and dogged in my determination to be an independent, intelligent thinker like him.

But that may have been my downfall in his eyes.

By the time I was three years old, the Mormon Church would become his family and his all-consuming mission. He had rallied against it for years as a rebellious young adult, questioning its rules, defying its restrictions, and flaunting his predilection for fun and frat parties. But then a “revelation” changed everything. Now, as a husband and father, he found Mormonism not only embracing but empowering. He would spend the rest of his life persuasively espousing its virtues and sharing its message. Just as he soared to the highest executive ranks at AT&T, he rose to the influential, hugely powerful positions of bishop and state president in charge of eight congregations, charming and cajoling his flock with promises of eternal rewards for a life lived well according to prevailing Mormon ideals. I alone remained an unconverted bane in his mission.

Listening to him denounce the lifestyle sins of a non-Mormon world, I was not convinced that his way was the right way. I wanted more, more opportunities to learn, grow, evolve. I wanted the freedom to follow my dreams and my spiritual path to become the woman I knew I was. I didn’t want to be subservient or self-dismissing like my fellow Mormon sisters. I couldn’t remain demure and deny my desires. I did not want to defer to a man, father, or husband. Mormons have a mission to spread the word about their eternal kingdom. I was a girl on a mission, all right, but not the Church’s mission. As far as my father was concerned, I was a rebel, and he spent our years together trying to change that.

Because of our opposing views on life and the Church, our relationship became more and more strained as I experienced more of life. I know he loved me, yet I feared him. He demanded perfection. I sought reality. He wanted me to fit into a mold. I wanted to break out of it. He discouraged my dating non-Mormon boys, and I found them much more interesting and fun than my Church-endorsed counterparts.

We did share a love of lovely things. A gifted writer, he taught me to appreciate poetry and classical music. We both admired fine antiques, were passionate about interior design, and held fast to our unwavering beliefs in self-sufficiency and free enterprise. That was our bond, our special connection, and I always remained grateful to him for teaching me to embrace the sensibilities and elegant refinements that define my life today. Sadly, the Church created a life-long schism between us that we couldn’t seem to overlook or overcome.

I realized early on that the best way to keep peace with my father was to stay under the radar, in conversation, in actions, and in all outward appearances. So while I appeased him by attending Brigham Young University, the college he and the Church chose for all good Mormons—especially for young women, whom it was generally understood would bring home a “returned missionary husband” along with their degree—once I was away from home, I started to think for myself in earnest. I had to adhere to a proper dress code under the threat of expulsion: no pants on campus, no sleeveless tops, prim attire at all times. But I shortened my hems when I took off for off-campus parties and dances where rock music, banned from campus life, liberated feelings unnaturally and forcibly repressed by the Church-run University, and tried to buck the system whenever I could.

I did come home engaged to someone I met in college, but my father was more than disappointed in my choice of life partner. I remember how he and my mother tried to do all they could to derail our relationship. That only furthered my resolve. I was married in a traditional ceremony in the Mormon Temple, secretly chafing under the required temple garments and restrictions imposed on me, albeit determined to be the best, most perfect wife I could be. Our union, ostensibly sealed for eternity, was tumultuous and trying. It lasted eleven years, produced two beautiful children, and took me to the East Coast, far from the Mormon stronghold I grew up in.

As my marriage unraveled, so too did my ties to the Church. My father’s controlling comments, once so strongly Church oriented, morphed into personal criticisms and judgments about my parenting, my career, my looks, my life choices. Behind my back, he tried to bribe my children into helping him bring me and our little family back to the Church so we wouldn’t be “cast out into the darkness.” It never worked.

Our last face-to-face conversation took place six months before he died and more than forty years after I left my father’s house as a married woman and traveled cross-country to start a new life. I flew out to California for my obligatory biannual visit, as always making sure my hair, clothes, and makeup were perfect before seeing him. I worried needlessly about whether I had gained that extra pound or two that my father would unfailingly and critically point out on my already model thin body, and I nervously anticipated whether I would measure up to the high standards and judgments that had plagued me all my life. Here I was, a successful career woman and the mother of two amazingly accomplished grown children, and yet I felt as vulnerable and insecure as I did when I was a little girl.

My father looked frail and beaten down by taking care of my Alzheimer’s-stricken mother, but his spirit was as strong as ever. He couldn’t let go of the fact that I had rejected his beloved faith, his spiritual laws. He implored me to return to the Church.

“I wish you would reconsider coming back to the Church,” he said as I bid him goodbye. “I don’t want to lose you and your family for all eternity.”

He unexpectedly passed away a few months later, never reconciling with the decisions I made about my life. I was sorry that he had never given me the emotional support and unconditional love I needed while he was alive and regretted the many father-daughter opportunities and conversations we missed. Was I ever worthy in his eyes? It’s amazing how much we crave affirmation from our loved ones, how their actions and words affect us on the deepest levels. I shuddered at the thought of carrying that burden with me for the rest of my days.

I sought out spiritual guidance rather than organized religion to find inner peace, taking comfort in the knowledge of the existence of a higher power and the possibility of messages from the other side. That’s how I found myself at one of Roland’s Channeled Messages for the Soul presentations in November 2008, not knowing what to expect but hoping for something nonetheless. What I received was more priceless than I could have ever imagined and set in a motion a series of “revelations” that have made all the difference for me in how I viewed my father.

Other than the hostess, I didn’t know any of the people in the room that day. I looked around at the men and women, young and old, who perched expectantly on the folding chairs that had been set out in a semicircle and took note of the boxes of tissues that had been strategically placed in between them. Then Roland walked into the room with a disclaimer about the experience we were about to embark on, saying that the messages some of us were about to receive may not be what we expected but that they would be exactly what we needed to hear.

He moved from person to person quickly, stopping to hold a hand, offer an embrace, examine a ring, share a story. His mannerisms took on the persona of loved ones communicating from beyond, arms crossed here, fingers pointing there, soothing touches reminiscent of tender partings, laughter, tears. His presence was riveting, his messages poignant and personal for the recipients. I held my breath as he walked over to me.

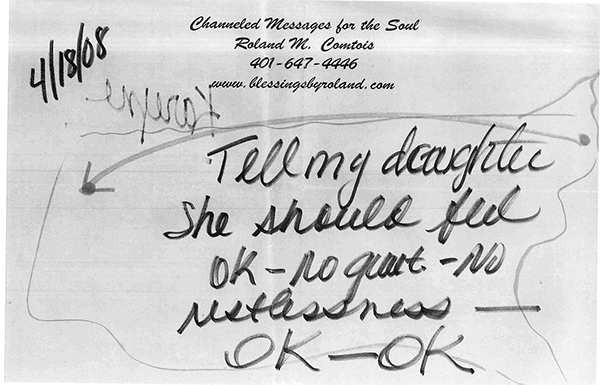

“Your father’s here. He said he is sorry for being so rigid and he has come to terms with the reality of spirit and religion. He had a spiritual awakening and he wants me to tell you …” Roland’s voice broke off in midsentence as he bounded to the front of the room to retrieve a large Purple Paper that had a map of the United States drawn on it with an arrow pointing from Connecticut to San Francisco. “This is for you,” he said. “Your father wants me to “‘tell my daughter that I am sorry she had to do so much traveling to California for the estate.’ ” And there was something else on it, a message written inside the outline of map:

“Tell my daughter she should feel OK—no guilt—no restlessness—OK—OK.”

It was dated April 2008. My father had passed away the first week in February. Since then, I had flown to California no fewer than five times, overwhelmed at having to deal with the exhausting cross-country flights, the stress and emotions that choked my every thought, the stacks and stacks of papers and receipts that overflowed from his desk and files. I was astounded that Roland had picked up on this and that my father knew how difficult these trips had been for me. Then there was that telltale expression my father was fond of repeating: OK, OK. When I read those two words, I actually heard his voice and knew at once it was, and could only be, a message from my father.

I saw Roland next a year later at a large group presentation in a historic mansion in Norwalk, Connecticut, when he had another Purple Paper message for me. It was dated March 26, 2009, and on it was the apology I waited a lifetime to hear.

“You were right. I was wrong.”

Bingo! I knew instantly what this meant. My father finally recognized and allowed me my spiritual quest and knew he had been wrong to force feed me the Mormon teachings.

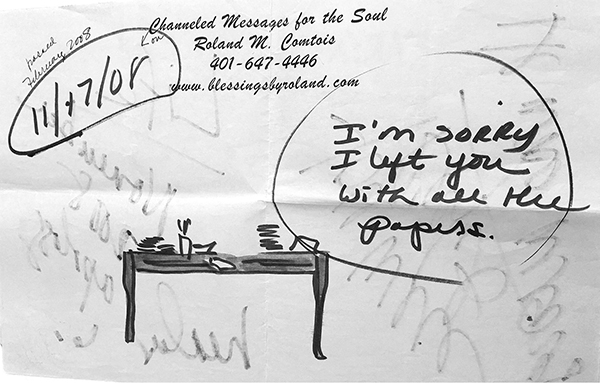

“Your father is here,” said Roland as he handed the paper to me. There was a big desk drawn on the paper with piles of papers on it. I recognized it immediately as my father’s. There was the unmistakable 1940s stapler with the rounded top that my father always kept on the desk, next to the leather pen and pencil cup. And the stacks and stacks of papers were placed exactly as I remembered them. It was an indelible icon from my childhood and Roland had portrayed the entire image as if he had seen it with his own eyes. It was a picture that needed no explanation. My jaw dropped. The paper read, “I’m sorry I left you with all the papers.”

“He wants me to tell you that ‘the vision of how you want to live your life and see your future is right. Keep going,’ ” Roland said.

I nodded, eyes glistening with unbidden tears, as I reached for the tissue I found being handed to me. There was no doubt that my father had sent these messages. I could feel my soul, my heart, start to heal.

There were to be four Purple Paper messages in all from my father to me, prerecorded and dated by Roland to reflect the day they were received and written.

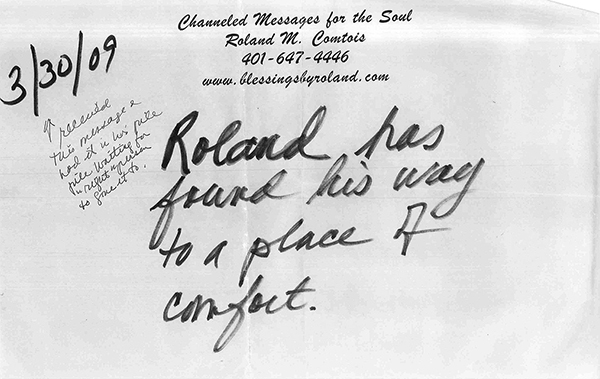

When we next met, Roland sought me out in the crowd. “I have been waiting to deliver this message to the right person,” said Roland, clearly confused by the name written on the paper. It was dated March 30, 2009. He handed it to me, saying, “I think this is for you.” I gasped out loud as I read it.

Written on it were the words “Roland has found his way to a place of comfort.”

The name Roland, my father’s name, was outlined in red. Red was his nickname, due to his red hair and his initials, R. E. D. Never in my discussions with Roland Comtois had my father’s name or nickname ever come up. The red outline around it erased any doubt about its origin and blew me away. Throughout his life, largely because of the unrelenting pressures and indoctrination by the Mormon Church, my father strived for perfection, always reaching for idealized goals that were unattainable here on earth. His expectations of me as his daughter were no less demanding and unrealistic. To know that a man so tortured in life had now found a place where he could relax and find comfort in just being himself was more than I could hope for. I breathed a liberating sigh of relief and experienced a lightness I had never known before. I had grown up with the notion that love was conditional and now, thanks to Roland’s Purple Papers, I knew that true love, eternal love, was freely given, no strings attached. His messages took away all the barriers and judgments that had existed between me and my father, absolved me from the self-defeating pain and anguish I had lived with for decades and wiped it all out, just like that.

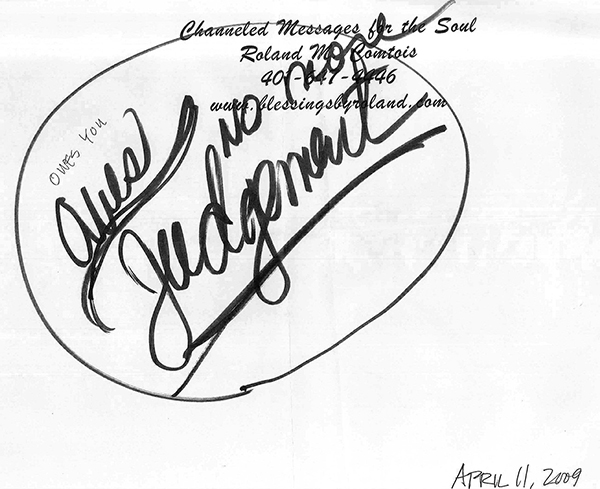

Everything dovetailed when I received the last of the Purple Paper messages from my father, dated April 11, 2009. “Your father says he owes you this,” Roland told me.

“Owes no more judgment.” These simple words written on purple paper had the power to change everything and instill the forgiveness I never imagined possible.