1

WHY CHRIST?

Christianity arose out of a particular human life ending in a disturbing, terrible death—then, resurrection. The meaning of Christianity is undecipherable without grasping the meaning of Christ’s life and death and living presence.

“Christ is the central spot of the circle; and when viewed aright, all stories in Holy Scripture refer to Christ” (Luther, Serm. on John 3:14). It is from Christ that Christianity derives its name, its mission, its identity, its purpose, its very life (Acts 11:26; John 15:1–5; Augustine, Hom. on the Epist. of John 1).

Christian Teaching Is Personally Grounded

At the heart of Christianity is a relation to a person. It is not essentially an idea or institution. It is a personal relationship to Christ. He is the one to whom faith clings and in whom faith trusts. “Being a Christian does not mean, first and foremost, believing in a message. It means believing in a person” (Gutiérrez, PPH: 130). Christian teaching hopes to show the way that leads to faith in this person. The Christian community emerges and lives out of personal trust in this person (Chrysostom, Comm. on John 57).

There is a discipline that attempts to understand this personal relation. The discipline belongs both in the academic world and the worshiping community. It studies God, hence is called theology. One of its major forms, Christian theology, studies God as known in persons who live their lives in close relation to this person.

Any who wish to reflect seriously upon Christian worship and the Christian life will want to know as much as possible about this relation. Those who are distracted from this purpose signal that they have elected not to inquire into classic Christian teaching, whose central interest is this relation. Those who remain focused on this inquiry must then try to understand why this one person is so important in this community.

Christians know God as the One revealed in Jesus. Other ideas in Christianity are measured in relation to that idea of God known in Jesus. The approach to that idea of God knowable only through the story of Jesus must begin with the study of Jesus himself.

His Unseen Influence

It is hard to think of a single person who has affected human history more profoundly than Jesus of Nazareth. This alone would make his story significant. Yet this is not the primary reason he is studied. He is not investigated as Alexander the Great or Napoleon would be—for their colossal power or dominance. His influence is not outwardly measured in terms of worldly power, but transforming power (Martyrdom of Polycarp; Athanasius, Incarn. of the Word 46–57; Clare of Assisi, Testament).

Historical study cannot ignore the history of Jesus. His footprints are all over human history, its literary, moral, and social landscape, and on every continent. Who has affected history more than he? No other individual has become such a permanent fixture of the human memory. He has been worshiped as Lord through a hundred generations.

Through the centuries Jesus has been memorialized in stone, painted on frescoes, and celebrated in song. Human history would not be our history without him. Something would be missing if historians ignored him or decided to study all figures except the one who has affected human history most. Indeed that is what makes it so puzzling when his name is purposely erased from high-school history texts.

The intellectual and moral reflection that has ensued from his life has penetrated every crevice of intellectual history, psychology, politics, and literature. One cannot understand human history without asking who Christ is and what he did and continues to do. No one is well educated who has systematically dodged the straightforward question—a question that committed Jews or Muslims may ask and study as seriously as Christians or agnostics or hedonists—Is Jesus the Christ?

The Decisive Question

Jesus turned this same question around when he asked Peter in a person to person voice: “But who do you say that I am?” Peter’s confession was clear: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Mark 8:29). This declaration remains the concise pattern for subsequent Christian confession, worship, and faith (Bede, Hom. on Gospels 1.16–17). In saying this, Peter stood in a personal relationship with another living person, Jesus of Nazareth—not with an idea, abstract system, or institution, but an actual you in a real relationship.

Note that the confession was not about Christ, but to him. Peter says: “You are the Christ” to one who is alive. If Christ is not still alive, forget about Christian confession—there is no one to whom to confess.

The meaning of Jesus’ life and death has never been a permanently obsolete issue to any generation since his appearance. It remains even today a matter of intense debate as to who Jesus was and what his life and death mean. Deeper even than the mystery of his historical influence is the simpler question that rings through Christian reflection: Why did God become human? (Anselm, Cur Deus homo).

Answering why is the subject of classical Christian teaching.

The Facts and Their Meaning

The bare facts of his life can be sparely stated. Date of birth: between 5 BC and AD 4. Place: Palestine. Ethnic origin: Jewish. Vocation: probably first a skilled construction artisan like his father, then a traveling preacher of the coming rule of God. Length of ministry: three Passovers (John 2:13; 6:4; 12:1). Date of death: Friday, 14 Nisan (the first month of the Jewish year), probably, by our calendar, April 7 AD 30 (or by some calculations 3 April, AD 33). Place of death: Jerusalem. Manner of death: crucifixion. Roman procurator: Pontius Pilate (AD 27–33). Roman emperor: Tiberius.

But the study of this person focuses not simply upon bare facts, but upon what his life meant—especially as it comes down finally to a single, decisive question: whether he is rightly understood as “Lord”—as the expected Messiah of Israel, Son of God—or not. There is no way to dodge this question so as to conclude that Jesus might be partially Lord or to a certain degree the Christ or maybe in some ways eternal Son or perhaps truly God. He must either be or not be the Messiah. He must either be or not be crucified and risen Lord of glory. Both women and men have given their lives to answer yes (Perpetua, Passion of the Holy Martyrs, Perpetua and Felicitas; Justin Martyr, First Apology 35).

The New Testament is bothersome because it calls upon every woman and every man within hearing distance to decide on their own about the true answer.

Person to Person: His Question to Us

Who Do You Say That I Am?

You. “Who do you say that I am?” This is the startling question that Jesus’ life constantly asks. The nearer anyone comes to him, the more clearly he requires decision. It is the unavoidable issue that the observer of Jesus’ life must finally struggle with. For Jesus himself presses the question and awaits an answer. To avoid that issue is to avoid him. To avoid him is to avoid Christianity altogether (Kierkegaard, TC: 66–71). Transformations occur when we listen. The closer we make him the object of our study, the more we become aware that he is examining us.

The evangelists’ portraits of his life, offered by eyewitnesses, are poignant, simple, and stirring. He was born of a poor family, of a destiny-laden but powerless nation. The earliest traditions report that he was born in a squalid cave or stable among animals in an out-of-the-way village. He immediately became the refugee baby of a fleeing family seeking to escape a wave of killing. The town he grew up in had the reputation that “nothing good could ever come from there.” He spoke a language (Aramaic) that few spoke then, and now has been virtually forgotten.

He is never said to have written anything except with his finger in the sand. He worked with his hands as a common laborer. He owned nothing of value. To the poor he brought good news of the coming governance of God. His disciples were simple folk, involved in artisan trades. They included some reprobates whose lives were reshaped by their unforgettable meeting with him. Even in the face of cynical criticism, he did not cease to dine and converse with outcasts, to mix with the lowly and disinherited. He washed the feet of his followers. He intentionally took the role of a servant. He reached out for other cultures despised by his own people. Of all the people who might have been able to grasp the fact that he was to be anointed to an incomparable mission, it turned out to be a “woman who was a sinner.”

Remarkable things were reported of him. He touched lepers. He healed the blind. He raised persons from the dead. These events pointed unmistakably to the unparalleled divine breakthrough that was occurring in his people’s history—the decisive turnaround in the divine-human story of conflicted love.

He heralded a new age. He called all his hearers to decide for or against God’s coming reign. He himself was the sign of its coming. He called for complete accountability to God. His behavior was consistent with his teaching. He was born to an ethnic tradition widely despised and rejected; but he himself became even more despised and rejected by many of his own people.

His enemies plotted to trap him and finally came to take his life. His closest friends deserted him when his hour had come to die. He knew all along that he would be killed. Sweat poured from his face as he approached death. He was betrayed by one of his closest associates. He submitted to a scurrilous trial with false charges.

His end was terrible. His back felt the whip. He was spat upon. His head was crowned with thorns. His wrists were in chains. On his shoulders he bore a cross through the city. Spikes were driven through his hands and feet into wood. His whole body was stretched on a cross as he hung between two thieves. All the while he prayed for his tormentors, that they might be forgiven, for they knew not what they were doing. He rose from the dead.

Is There a Plausible Explanation?

This is a sketch of the Gospels’ portrait of Jesus. It is this one whom the disciples experienced as alive the third day after his death. This is the unique person whose extraordinary life we now try to understand.

How is it plausible that two thousand years ago there lived a man born in poverty in a remote corner of the world, whose life was abruptly cut short in his early thirties, who traveled only in a small area, who held no public office, yet whose impact upon us appears greater than all others? How is it that one who died the death of a criminal could be worshiped as Lord by billions?

This is the surprising paradox of his earthly life, but even this is not its deepest mystery. Why are people willing to renounce all to follow him and even die in his service? How is it possible that centuries later his life would be avidly studied and worshipers would address their prayers to him? What accounts for this surprising relation he has with this community?

Classic Christian teaching answers without apology: what was said about him then is true now; he actually was:

Son of God,

promised Messiah,

the one Mediator between God and humanity,

truly God

truly human,

who liberated humanity from the power of sin by his death on the cross,

who rose from the dead to confirm his identity as the promised one.

That answer better explains what his life is and means than any of its alternatives. It is theoretically possible for the study of Jesus to function without that basis, but in practice it is exceptionally difficult, for one is then forced to stretch and coerce the narratives to make any sense of them at all. The New Testament documents give determined resistance to any reader who discards that hypothesis (Jesus is Lord) because they imagine that they know a better explanation of his true identity. There is no other or better way to explain this amazing life. According to Christian confession, Jesus is either Messiah or nothing at all.

The study of Christ (Christology) is that discipline that inquires critically and systematically into this person, his relation to his Father and to us. In him the true relation between God and ourselves is alleged to be knowable.

Studying Him as One Who Is Following Him

I may be saved by grace through faith without passing an examination on Christology. But his life compels some explanation. When he tells me that my eternal destiny depends upon trusting in him, what am I to say? His life and death remain the central point of interest of Christian discipleship and education.

He is not fully studied as if only a man, though he was a man. This is a man for whom studying him means following him in his way. He cannot be studied in a book alone but on a long road.

The events surrounding this individual are alleged to stand as the supreme truth of the history of revelation. The study of Christ implies the study of the divine plan for which humanity was created. In him the purpose toward which history is moving is allegedly revealed. In Christ God actively embraces wounded humanity and enables humanity to answer to God’s active embrace.

This is not a study that can be rightly undertaken by those who remain dogmatically committed to the assumption that nothing new can happen in history or that no events are knowable except those that can be validated under controlled laboratory conditions. Here the laboratory is life, human life, human history, cosmic history.

The Study Occurs in the Midst of a Worshiping Community on Pilgrimage

The meaning of Christ’s life is studied within the context of a worshiping community, just as Islamic theology occurs within the community of Islam. No one can study basketball without ever attending a basketball game. The “game” in this case is a living person, Jesus Christ. If the once dead, now living Christ is regarded as now finally dead and gone, the game is not being played.

The New Testament itself frequently disavows that it contains an entirely new idea or understanding of God, for the one known in Jesus was already many times promised in history before Jesus, as seen in the Law and Prophets (Heb. 1:1–5). Yet in Jesus the reality of God is brought home and relationally received in an unparalleled way.

Our purpose is to understand and teach Jesus the Christ as he has been understood and taught by those whose lives have been most profoundly transformed by him. If we were studying Hasidic Judaism, we would hope the same of a Hasidic teacher. If we were studying Islamic Sufism, we would hope the same of a Sufist teacher. Christians also do well to study honestly the Vedas, Tao, the Mishnah, Gemara, Tosefta, or the Qur’an as carefully as they would hope others might take the New Testament. Let the evidence be fairly presented. Christian teaching does not wish to obstruct other voices from presenting competing claims or contrary evidence, but to ensure the accurate presentation of its own evidences.

Jesus’ life has been at times partially, wrongly, or self-interestedly remembered. From these aberrations and digressions have flowed vexations for humanity: wars, divisions, inequities, and systemic injustices. A poorly developed, ill-formed understanding of Jesus Christ has at times blocked off the Word that he intends to speak to us. They have stunted the personal relation he offers us. Hence it is imperative to think clearly about him if we are to understand the personal relationship he offers.

The Meaning of “God” Is the Meaning Christ Has Given to the Name

The meaning of the word “God” is for Christians the meaning given the name of God by Jesus.

Many morally concerned Christians can honestly understand the church’s speech about the Father and the Spirit more readily than about the incarnate Son. The classic Christian teachers respected those whose integrity requires that they raise ethical questions earnestly and historical questions rigorously (Justin Martyr, Trypho; Origen, Ag. Celsus; Augustine, Ag. the Skeptics). That determination made them all the more determined to communicate the meaning given to the name God by Jesus.

Note this irony, however: Those who most doubt his claims often have been already seized in awe by those claims. They would not be so earnestly inquiring and doubting if the majesty of his presence were not so real. Hence it is often said, as Jesus himself said, that earnest doubters and idolaters may be nearer to salvation than those still morally asleep. Some who have been most actively engaged in social justice and political change who deny the identity ascribed to Christ by the apostles may nonetheless remain profoundly affected by his continuing presence. Many are struggling for justice because they have first undergone the pedagogy of his meekness, peacemaking, and hope. Those who most wearily wonder about the mystery of Christ have often been deeply affected by him already, and may by study come to that self-recognition.

This principle, aptly stated by John Knox, remains applicable to a secular-weary culture that is once again actively turning toward a new encounter with Christ: “Whether we affirm or deny, the meaning of ‘God’ is the meaning which Christ has given to the name” (MC: 7). H. R. Mackintosh remarks in the same vein: “The name of God has the final meaning that Jesus gave it…. He is an integral constituent of what, for us, God means” (PJC: 290, 292). The defining meaning of God for Christians is that meaning most clearly made known in Jesus’ life.

Identification with the Lowly

The incarnation is God’s own act of identification with the broken, the poor, with sinful humanity. God did not enter human life as a wealthy or powerful “mover and shaker.” God came in a manger, amid the life of the poor, sharing their life, identifying with the meek.

There is embedded deeply in the best of early ecumenical teaching a pungent critique of sexual inequalities and of the propensity of male users of power to abuse that power. Gregory the Theologian pointed out in the fourth century that “the majority of men are ill-disposed” to equal treatment of women, hence “their laws are unequal and irregular.” Does a husband who is unfaithful to his wife “have no account to give? I do not accept this standard; I do not approve this custom.” (Gregory of Nazianzus, Orat. 37.6, italics added).

When political activists imagine that only they are capable of providing a critique of the dynamics of social oppression, it is fitting to note this powerful strain of early Christian social criticism. The theologies of liberation still await a greater dialogue with classic Christian teaching. Marxist critics were not the first to ask about social location of interpreters or for an economic account of injustice. These criticisms run deep within early Christian history (Oden, The Good Works Reader, 2007). The ethical consequences of the gospel have been often grasped by those inquiring into Jesus Christ (notably Clement of Alexandria, Chrysostom, Ambrose, Francis of Assisi, Menno Simons, Grotius, Zinzendorf, and the Blumhardts).

It is not enough to speak of God’s own redemptive coming as if it lacked social consequence. These consequences have been spelled out in different cultures by Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, Calvin, Hooker, and Wesley. What that means for the increase of love and justice in society has been repeatedly addressed prior to our times, notably in such figures as W. Wilberforce, Phoebe Palmer, F. D. Maurice, J. H. Newman, and W. Rauschenbusch. None of these attempts to transform culture has a perfect score. But where does any perfect score appear within any human culture?

The temptation toward a moralized narrowing of theology into ethics seems to be an essential feature of all modern Christian thought (P.T. Forsyth, PPJC, 7, 9). That narrow view can be opened up by serious digging into classical Christian teachings concerning Jesus.

The plea for ethical accountability in speech about God is justified. It is a test that classical Christianity passes better than much modern Christianity (Athanasius, Incarn. of the Word 46–57: Augustine, CG 14). This moral narrowing that remains endemic to popular modern religiosity runs the risk of reducing the Word of Life to moralism (Fitzsimons Allison, The Rise of Moralism). Since Feuerbach and Nietzsche it has been a standard conceit of western intellectuals to suppose that a high view of the Son of God necessarily promotes a low view of moral responsibility. Those who buy into Marxist economic interpretation repeatedly sound this alarm. Such distortions are inconsistent with classical Christian teaching, where the assumption prevails that the confession of Jesus Christ as Lord has insistent moral meaning and culture-edifying implications. Christians who call for an identification with the poor do so out of a long tradition of voluntary poverty and generous giving, which follows from Christ’s willingness to become poor for our sakes.

Jesus Himself Is the Good News

Jesus did not come just to deliver good news, but to be himself the good news. The gospel is the good news of God’s own coming. Jesus is its personal embodiment. The cumulative event of the sending, coming, living, dying, and continuing life of this incomparable One is the gospel.

The gospel does not introduce an idea but a person—“we proclaim him!” (Col. 1:28, italics added). The “him” proclaimed is one whose life ended in such a way that everything that has occurred before and after has become decisively illumined by his epic narrative. “Him we proclaim, warning every man and teaching every man in all wisdom, that we may present every man mature in Christ” (Col. 1.28). What was written about him was not written simply as biography but as a gift and a living challenge. For biographies are written of persons who are dead, thus inactive. A biography is a written history of a person’s whole bios (“life”). A biography of a person still alive is by definition incomplete. Rather the gospel is the account of a person who remains quite active, palpably present, whose heart still beats with our hearts, one who died who is now alive (Augustine, CG 13.18–24; Bonhoeffer, Christology).

The Gospel: A Summary of the Person and Work of Christ

Reflections on Jesus are often divided into discussions of his person and work, that is, who he was and what he did. The good news (euaggelion, gospel) unites these two: the person of the Son engaged in the work of the servant-messiah. These are united in the good news of human salvation. “Gospel” is the unique term that concisely summarizes and links the person and work of Christ. Only this person does this work, which constitutes God’s good tidings to human history.

“Gospel” (eua gelion) is a distinctive New Testament theme, occurring over one hundred times, and embedded in Jesus’ preaching from the outset. His coming was announced as “good news of great joy that will be for all the people” (Luke 2:10; Cyprian, Treatises 12.2.7). “I must preach the good news of the kingdom of God to the other towns also, because that is why I was sent” (Luke 4:43; Tertullian, Ag. Marcion 4.8). The medieval Anglo-Saxon root (godspell) meant “good news” or “glad tidings” (Anglicizing the Latin bonus nuntius). The gospel, Luther thought, is to be sung and danced (Intro. to NT, WLS 2:561, commenting upon David bringing the ark to the City of David, 2 Sam. 6:14; cf. Maximus of Turin, Sermon 42.5; Gregory I, Morals on Job 27.46).

gelion) is a distinctive New Testament theme, occurring over one hundred times, and embedded in Jesus’ preaching from the outset. His coming was announced as “good news of great joy that will be for all the people” (Luke 2:10; Cyprian, Treatises 12.2.7). “I must preach the good news of the kingdom of God to the other towns also, because that is why I was sent” (Luke 4:43; Tertullian, Ag. Marcion 4.8). The medieval Anglo-Saxon root (godspell) meant “good news” or “glad tidings” (Anglicizing the Latin bonus nuntius). The gospel, Luther thought, is to be sung and danced (Intro. to NT, WLS 2:561, commenting upon David bringing the ark to the City of David, 2 Sam. 6:14; cf. Maximus of Turin, Sermon 42.5; Gregory I, Morals on Job 27.46).

The Second Helvetic Confession sparely defined the gospel as “glad and joyous news, in which, first by John the Baptist, then by Christ the Lord himself, and afterwards by the apostles and their successors, is preached to us in the world that God has now performed what he promised from the beginning of the world” (13, BOC 5.089, italics added; Ursinus, CHC: 101). God is now fulfilling what had been promised all along (Origen, OFP 4.1).

The good news of Jesus’ coming was understood as fulfillment of prophetic expectation, as in Isaiah: “How beautiful on the mountains are the feet of those who bring good news, who proclaim peace, who bring good tidings, who proclaim salvation” (Isa. 52:7; Irenaeus, Ag. Her. 3.13; Eusebius, Proof of the Gospel, 3.1). In Isaiah’s time the good news referred to the return of Israel from exile, yet it prefigured Jesus’ proclamation of deliverance of all humanity from sin (Augustine, CG 18.29; Calvin, Comm. 3:99–101).

The Earliest Christian Preaching in Acts

The earliest interpretations of the meaning of Jesus’ life are found in the oral traditions that flowed into the preaching reported in Acts (M. Hengel, Acts and the History of Earliest Christianity). That preaching has been concisely summarized by C. H. Dodd (APD: 21–24) in these six points:

- “God fulfilled what he had foretold through all the prophets, saying that his Christ would suffer” (Acts 3:18; 2:16; 3:24).

- This has occurred through the ministry, death, and resurrection of Jesus, of Davidic descent (Acts 2:30–31), “a man accredited by God to you by miracles, wonders and signs” (Acts 2:22).

- “God raised him from the dead” (Acts 2:24; see 3:15; 4:10), making him Lord and Christ (Acts 2:33–36), and “exalted him to his own right hand as Prince and Savior that he might give repentance and forgiveness of sins to Israel” (Acts 5:31).

- God has given the Holy Spirit to those who obey him (Acts 5:32). “Exalted to the right hand of God, he has received from the Father the promised Holy Spirit and has poured out what you now see and hear” (Acts 2:33).

- Christ “must remain in heaven until the time comes for God to restore everything” (Acts 3:21; 10:42). Having suffered as Messiah and having been exalted as Messiah, he would return as Messiah to bring history to a fitting consummation. So:

- “Repent and be baptized, every one of you, in the name of Jesus Christ for the forgiveness of your sins. And you will receive the gift of the Holy Spirit” (Acts 2:38).

These points recapitulate the core of the earliest Christian preaching. Subsequent creedal confession would generally adhere to this sequence and build upon it (J. N. D. Kelly, Early Christian Creeds; SCD; CC; COC 1).

The Pauline Kerygma

Paul’s conversion is usually dated to a short time after Jesus’ death. He understood himself to be passing on to others the tradition he himself had received from the risen Lord (1 Cor. 15:1–7; 16:22). Hence the earliest layer of Paul’s proclamation could hardly be assumed to have undergone extensive changes, philosophical mutations, or ideological developments that would have required considerable time to emerge and become integrated into other communities.

The alternative hypothesis is implausible—that Paul might have been surreptitiously passing on to Corinth views that had only later gradually developed between AD 33 and 50, for he himself specifically notes that this is the tradition he received, transmitting to Corinth what had been transmitted to him “from the beginning straightway” (“from the outset,” 1 Cor. 15:3; Chrysostom, Hom. on First Cor. 38). Paul specified his primary sources for the oral tradition he passed on, for he personally knew and had received “the right hand of fellowship” from “James, Peter and John, those reputed to be pillars” of the earliest Christian community (Gal. 2:8–9; Marius Victorinus, Epist. To Gal. 1.2.7–9), and from the risen Lord.

The gospel Paul had earlier received and subsequently passed on was carefully preserved in a Letter whose authenticity is seldom disputed: “Now, brothers, I want to remind you of the gospel I preached to you, which you received and on which you have taken your stand. By this gospel you are saved, if you hold firmly to the word I preached to you. Otherwise, you have believed in vain. For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day” (1 Cor. 15:1–4; Chrysostom, Comm. on Cor. 38.2–5).

The core of Pauline preaching was collated and summarized by C. H. Dodd:

The prophecies are fulfilled, and the new age is inaugurated by the coming of Christ.

He was born of the seed of David.

He died according to the Scriptures, to deliver us out of the present evil age.

He was buried.

He rose on the third day according to the Scriptures.

He is exalted at the right hand of God, as Son of God and Lord of quick and dead.

He will come again as Judge and Savior of men.

(APD: 17)

There is strong evidence that the earliest Christian proclamation attested Jesus as Kurios (Lord), confirming Luke’s report of Peter’s first sermon in Acts 2:36. In debating the scribes, Jesus made it clear that the Messiah was not merely David’s son, but David’s Lord, implying that he himself was this divine Lord (Mark 12:37; Augustine, Tractates on John, 8.9; Taylor, NJ: 50–51; Ladd, TNT: 167–68). If so, this earliest Christian ascription of Lordship comes from Jesus himself and not from his disciples alone. This passage undercuts the common form-critical habit of late dating, which theorizes that the ascription of deity only slowly evolved and that Lordship was only much later attributed to Jesus (Bultmann, TNT 1: 121–33).

The earliest Christians were rigorously monotheistic, worshiping and proclaiming the one God. It was as monotheists that they worshiped and proclaimed Jesus Christ as Lord (Ursinus, CHC: 202–204). Thus the kernel of triune teaching was already firmly implanted in this earliest core of Christian confession (Pearson, EC 1: 260–75).

Early Creedal Summaries

Second century creedal digests echoed these primitive New Testament confessions. Ignatius (ca. AD 35–107) provided this early summary of core events that were to form the second article of the Apostles’ Creed on Christ: “Be deaf, therefore, whenever anyone speaks to you apart from Jesus Christ, who is of the stock of David, who is of Mary, who was truly born, ate and drank, was truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, was truly crucified and died in the sight of beings of heaven, of earth and the underworld, who was also truly raised from the dead” (Ignatius of Antioch, Trallians 9:1–2).

Irenaeus (ca. AD 130–200) was firmly convinced that the following confession had been reliably received directly from the apostles themselves and had not passed through a series of dilutions resulting from its development: “The Church, though scattered through the whole world to the ends of the earth, has received from the Apostles and their disciples the faith…in one Christ Jesus, the Son of God, who became flesh for our salvation” (Irenaeus, Ag. Her. 1.10.1). These short creedal confessions were designed to be memorized verbatim at baptism, in order that believers may have “salvation written in their hearts by the Spirit without paper and ink” (Irenaeus, Ag. Her. 2.4.1; Cullmann, Earliest Christian Confessions).

Far from being appended to Scripture, the baptismal rule of faith was understood as a summary of Scripture that contained nothing other than the teaching found in the earliest eyewitnesses who penned the Scripture (Pearson, EC I: 383). For this reason, since it was directly quoting the apostles, the rule of faith as recalled and passed on by Tertullian was understood by the church of North Africa to be resistant to any possibility or need of change or supposed “improvement” (irreformabilis; On the Veiling of Virgins 1).

The Heidelberg Catechism followed this same pattern: “What, then, must a Christian believe? All that is promised us in the gospel, a summary of which is taught us in the articles of the Apostles’ Creed, our universally acknowledged confession of faith” (II, Q22, BOConf. 4.022). Protestant confessions such as the Second Helvetic characteristically accepted the classical Christian teaching of ancient ecumenical formulae “summed up in the Creeds and decrees of the first four most excellent synods convened at Nicaea, Constantinople, Ephesus and Chalcedon—together with the Creed of blessed Athanasius, and all similar symbols,” and “in this way we retain the Christian, orthodox and catholic faith whole and unimpaired” (Confession 11, BOConf. 5.078). Orthodox, Catholic, and Protestant doctrinal definitions share this common consensus. It is to these ancient ecumenical formulations and their leading expositors that classic consensual Christian teaching primarily appeals, provided that “nothing is contained in the aforesaid symbols which is not agreeable to the Word of God” (Second Helvetic Confession 11, BOConf. 5.079).

The Gospel of God

It is this good news that awakened the church. Since the gospel brought the church into being, the church cannot claim to be sole arbiter of the gospel, but must humbly receive it (Eph. 5:23; Col. 1:18–24; Ursinus, CHC: 102–104). The church does not possess or own or contain the gospel. The very purpose of the church is to proclaim and make known the gospel that calls the church into being (Luther, Serm. at Leisnig [1523]; Melanchthon, Loci Communes).

Paul defined the subject of his letter to Rome as the “gospel of God” (Rom. 1:1; Origen, Comm. on Rom. 1.1–2). Mark entitled his narrative “the gospel of Christ” (Mark 1:1). Both thereby underscored the transcendent origin of the events surrounding Jesus of Nazareth.

The deepest need of humanity is for salvation from sin. This is the quandary to which the gospel speaks. The church that forgets the gospel of salvation is finally not the church but its echo. The church that becomes focused upon maintaining itself instead of the gospel becomes a dead branch of the living vine. The church is imperiled when it becomes intoxicated with the spirit of its particular age, committed more to serve the gods of that age than the God of all ages (Augustine, CG 4; Kierkegaard, Judge for Yourselves!; Two Ages).

Key Definitions: Person, Work, States, and Offices

Shorthand terms have often been used in the ecumenical tradition to encompass large masses of dialogue and consensual thinking into condensed formulae. In what follows I will introduce the most important of these terms pertaining to Christ, namely, those distinguishing between Christ’s person, his work, his states of descent and ascent, and his offices (prophet, priest, and king). Time is saved by carefully learning and remembering these distinctions from the outset.

The Person and Work of Christ

The overall design of classical Christology is essentially simple and need not be confusing even to the novice. It hinges on a clear-cut distinction between who one is and what one does. A living person is not the same as that person’s work. The work (opus) is done by the person (persona, Gk. hupostasis). We do not commonly say that the person’s work is precisely the person, because the person precedes and transcends his work. Rather we say the person’s work (acts, actions, behaviors) reveals who the person is. Hence person and work are distinguishable, but not separable.

Nothing proceeds rightly in setting forth the work of Christ unless the unique Person doing the work is first properly identified. Every person is unique. But the Person of Jesus Christ is unique in a way that is utterly distinguishable from all other unique persons, since without ceasing to be human, this person is God in the flesh.

The work done by Jesus Christ could not have been completed by any other Person than one distinctly capable of mediating the alienated relationship between deity and humanity. To reconcile that relationship, one must have personal credentials in both ordinary humanity and true divinity. The reconciler must have standing with humanity and have standing with God. One must have a particular identity, a unique personhood to do that work (Leo I, Serm. 27; 63).

Classic exegetes thus begin their reflection with the distinctive identity of Christ, or the person of Christ as truly human and truly God—who he is (Augustine, Trin. 4; Hilary, and Gregory of Nazianzus on second article of the Trinity). For no one could fully accomplish this task unless that one were truly human and truly God.

Theandric Union: The Deity of Christ Is the Premise of His Saving Activity

Quietly operating in the overall design of classic Christian teaching is the principle of economy (oikonomia—the arrangement, plan, order, design of the foreseeing God). The central ordering economic principle of all talk of the person of Christ is the union of his humanity and divinity, one person having two natures. This is called the theandric (divine-human) premise (or the premise of theandric union). Theandric is a contraction of two words: theos and anthropos (theanthropos = God-man; Augustine, Trin. 1.13).

The mission of divine grace is the central ordering principle of all talk of the work of Christ, encompassing his life, death, exaltation, and continuing presence. “The doctrine of the mediator consists of two parts: the one has respect to the person of the mediator; the other to his office” (Ursinus, CHC: 164 italics added). An intrinsic order is here implied. One must first establish the personal identity of the Son, and only on that basis can one consider the work of the Son or the saving action of God in Jesus Christ. That is the sequence through which classic Christian teaching proceeds.

Person and work, though conceptually distinguishable, are intrinsically related, hence inseparable, always appearing together (just as you are presupposed in what you do, your acts cannot be considered apart from you). There is no mediation between God and man without this mediator who must be truly God and must be truly human.

The saving significance of his work for us is the reason why we study his person, his unique divine-human identity. Who Christ is is necessary to what he does. What he does proceeds from who he is. Melanchthon rightly understood: “Who Jesus Christ is becomes known in his saving action” (Loci, pref., CR 21:85).

The Order of Deity, Humanity and Union: The Key Issues of the Person

There is an aesthetically beautiful simplicity in the ordering of classical Christology. It examines in compact sequence three questions: the deity of the person; the humanity of the person; and the unique personal union of God and humanity in one person (Athanasius, Four Discourses Ag. Arians 3:26–28; Novatian, Trin. 9–28). The most decisive questions associated with the identity of Christ fall under one of these three:

- Is the Son truly God?

- Is the Son truly human?

- If both are answered yes, then how can these two affirmations be made to cohere?

This is the classic trajectory we will track in the ensuing chapters.

The Order of Salvation: The Basic Issues of His Work

Only when the classic exegetes had identified the Worker did they speak of the work of the Savior. The work of Christ is a phrase that sums up all the saving activity of God the Son on behalf of humanity. Whatever he has done that has saving significance is viewed all together as his saving work. Under the rubric of the work of Christ we will speak more broadly of his birth, life, and teaching, but focus primarily on his mission, death, and resurrection, as do the gospel narratives.

The study of salvation is called soteriology (peri tes sōtērias logo—that which concerns the Word of salvation). It studies the reconciling work this unique Person came to accomplish: the redemption of humanity. The Mediator came to mediate between God and humanity in a redemptive work that could only be accomplished by this unique Person. The study of God’s saving action includes the work of redemption (the atoning death and victorious resurrection) and the receptive application of that work in the community of faith and the world. The door of entry into the study of salvation is the discussion of the estates and offices of the Redeemer.

The order of salvation (ordo salutis) proceeds from person to work. The work includes everything from his descent from heaven to his ascent to heaven.

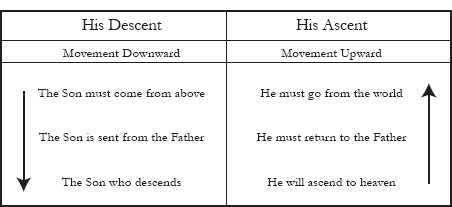

The Descent and Ascent of the Son

For this Person to do this work, it was necessary that he come to humanity in a manner fitting to his theandric identity. Humbled from an exalted state, he came to share in our human sphere in life and death. Having accomplished this mission, he returned as resurrected Lord in exaltation.

The redemption envisioned by God in eternity was accomplished in time by his Son Jesus Christ. Hence the whole complex story of his coming and going may be summarized in two basic states or phases. Classic Christianity plots the entire narrative in these movements:

Classic Christianity teaches that the Son who descends must ascend. The usual way of expressing these phases doctrinally is:

|

Humiliation |

Exaltation | ||

|

From incarnation to death |

From resurrection to heavenly session |

||

|

katabasis (descent) |

anabasis (ascent) |

Thus it is summarily said that the Son appeared in two states (“estates” or conditions), first as lowered, then as raised.

Humiliation does not mean that God has been degraded or diminished, but rather that God the Son freely enters our human condition by becoming flesh and becoming obedient unto death and burial (Phil. 2:6–9), after which there can be no further humbling. Then he is exalted to return to the bosom of the Father (Hilary, Trin. 2, 22; Longenecker, CEJC: 58–63).

The Offices of the Earthly Work as Prophet, Priest, and King

An office is a position of trust, an assigned service or function, with specified duties and authority. The ancient Hebraic offices to which the expected One would be anointed were prophet, priest, and king. These provided a sufficient frame of reference for organizing and summarizing the whole redemptive work of Christ on earth within the bounds of his descent and ascent.

- as prophet he taught and proclaimed God’s coming kingdom;

- as priest he suffered and died for humanity;

- as king he is exalted to receive legitimate governance of the coming reign of God.

Sequential Correlation of Estates and Offices

Note that there is a sequential correlation between the two estates and three offices: he is humbled to undertake his earthly prophetic ministry, which ends in his priestly ministry; he is exalted to complete his ministry of governance in guarding and guiding the faithful community toward the fulfillment of the promises of God. One who grasps this sentence thoroughly has already touched the vital center of the inner structure of classic reasoning about the Word of Life. We will make clear each of its elements as follows.

Surveying the Christological Landscape in Advance

Looking ahead in overview: Even a beginner in the study of Christian teaching can distinguish between (1) the person and work of Christ, (2) the two natures of the one person in theandric union, (3) death and resurrection as key to the work of Christ, (4) the two estates, and (5) the three offices by which he accomplished his work.

These simple terms grasp the essential structure of classical Christology. Everything else falls into place in relation to this clear-cut structure. Classic Christianity seeks to make these distinctions plain and useful for baptismal instruction, discipling, and spiritual formation.

The order we are following is a composite of patterns formulated by the most deliberate systematic minds of the early periods of Christian teaching: Irenaeus, Tertullian, Gregory of Nazianzus, Cyril of Jerusalem, Hilary of Potiers, Augustine, and John of Damascus. This sequence is found in all of these figures. This sequence owes very little to any writer after the eighth century.

The same sequence is found in the structure of Thomas Aquinas’ treatise on the Savior. It falls into two major divisions:

|

The Mystery of the Incarnation |

The Mystery of Redemption | ||

|

The Person of Christ |

The actions and sufferings of Christ | ||

|

Divine-human union (Christology, ST 3 Q48–51) |

Birth, life, death, exaltation (Soteriology, ST 3 Q52–55) |

Calvin’s similar order (Inst. 2.14–17) has profoundly shaped Protestant Christology:

|

Two Natures United |

Order of Offices |

Descending and Ascending States | |||

|

Shows how the two natures of Mediator unite in one Person (Inst. 2.14) |

Prophet Priest King (Inst. 2.15) |

Christ has fulfilled the work of Redeemer to acquire salvation for us by his birth and death through DESCENT, and through his resurrection and ascension by ASCENT (Inst. 2.16–17) |

The Name Jesus Christ Encompasses His Person and Work

Christ (Messiah) is a title, Jesus a personal name. The unified name Jesus Christ welds together the person and office of the Savior. The inclusive name itself reveals the heart of the interfacing of the Jesus of history and the Christ celebrated by faith.

This office (Christ) cannot be viewed or understood apart from this person (Jesus). The person is never seen or attested “off duty” or as separable from the office, for Jesus is always the sent Son, the anointed One, whose work is the giving of himself, whose person is the Word made flesh, whose enacted word is his life. He cannot be reduced either to Jesus or the Christ as if divisible. The narratives of Jesus do not mention anything he did that could be understood as disconnected from who he was as Sent and Anointed One.

The teachings of Jesus are important to faith not simply because they are profound ideas, but because they are the teachings of this incomparable Mediator, Jesus Christ. There is no mention of his teachings whatever in the Apostles’ Creed and no attempt in any of the classic confessions to set forth the teachings of Jesus as conceptually separable from his person and work. His teaching with words is made clear in his embodied Word, the embodiment and personification of his teaching in his ministry and death and resurrection.

Faith in Jesus Christ is not the acceptance of a system of teaching or doctrine, but personal trust in him based upon an encounter with this living person whose life is his word and whose word is embodied in his life. His message is proclaimed only through his action, especially in the events surrounding his death. Jesus not only has a word to speak for humanity but himself is that Word. He not only does good works but also is the inestimable good work of God on our behalf.

This is why the most basic form of Christian confession is that Jesus Christ is Lord, which presupposes the pivotal recognition that Jesus is the Christ. Nothing is more central to New Testament documents than that confession based on that recognition. This is the quintessential integrating statement of the person and work of Christ.

Yet modern criticism has despairingly sought for a century to pry Jesus loose from his identity as the Christ on the one hand (Harnack and the German liberal tradition focusing separately upon Jesus’ teachings) or from any significant correlation between the remembered kerygma of the disciples with the known historical person of Jesus (Bultmann and Tillich, who had grave doubts that anything at all can be reliably known about Jesus, even though the community’s memory of the kerygma might be proximately known). Both the liberal tradition and the post-liberal tradition failed to sustain the orthodox apostolic witness by disuniting the Word from the historicity of the teacher.

The Nicene Organizing Principle of the Classic-Ecumenic Study of Christ

The prevailing organizing structure for the classic sequence of Christian teaching of Christ is found in the second article of the Creed of the 150 Fathers of the Council of Constantinople (traditionally called the “Nicene Creed,” but more accurately called the Nicaea-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381).

This creed may be found in virtually any prayerbook or hymnbook of the Christian tradition—Catholic, Orthodox, liberal or evangelical Protestant. It contains everything essential to this study and to Christology. Classic Christology consists in a commentary on the sequence of key biblical phrases compacted in the creed.

The three articles of the creed reveal its deliberate overarching triune structure, confessing faith in one God: God the Father, God the Son, and God the Spirit. Having already looked into the first article on God the Father in the first part of this study (“The Living God”), we will now treat point by point the series of topics of the second article on God the Son, leaving it to the end of this study to discuss the third article on God the Spirit. In this way it becomes clear how the whole of theology is a preparation for and confirmation of baptism.

Luther thought that “all errors, heresies, idolatries, offenses, abuses and ungodliness in the Church have arisen primarily because this [second] article, or part, of the Christian faith concerning Jesus Christ, has been either disregarded or abandoned” (Lenker ed., 24:224). “You must stay with the Person of Christ. When you have Him, you have all; but you have also lost all when you have lost Him” (Luther, Serm. on John 6:37).

Outline of the Central Article of the Nicene Creed

Note that the creed’s second article is ordered according to the pivotal twofold division that summarizes classic Christology: the person and the work of Christ (who the Redeemer is and what the Redeemer has done to redeem humanity), conceptually distinguishable yet practically united in a single integrated gospel. In this way the creed provides the core outline of this inquiry (with key Greek and Latin terms), as follows:

PART I. Who Christ Is—Word Made Flesh

Faith in the One Lord: Truly God, Truly Human

Personal trust: I believe (credo; Gk. pisteuomen).

Belief in one Lord (in unum Dominum; Gk. eis ena Kurion).

Confession of the Name Jesus Christ

I believe in Jesus (Credo in…Jesus).

Jesus is the Christ (Christum), anointed as proclaiming prophet, self-offering priest, and messianic king.

One Person: Deity and Humanity in Theandric Union

Only Son of God (Filium Dei; Gk. ton huion tou theou ton monogenē).

The Son is eternally Begotten (unigenitum; Gk. monogenē, “only-begotten”).

Of the Father (ex Patre natum; Gk. ton ek ton patros gennēthenta).

Begotten before all worlds (ante omnia saecula; Gk. pro pantōn tōn aiōnōn).

True God

The Son is God of God (Deum de Deo).

The Son is Light of Light (Lumen de Lumine; Gk. phōs ek phōtos).

The Nature of Divine Sonship

The Son is true God of true God (Deum verum de Deo vero; Gk. Theon alethinon ek Theou alēthinou).

The Son is begotten, not made (genitum, non factum; Gk. gennēthenta, ou poiēthenta).

The Son is consubstantial with the Father (consubstantialem Patri; Gk. homoousion tō Patri, of the same essence as the Father).

Creator and Savior as Preexistent Word: The Preincarnational Life of the Son

By the Son were all things made (per quem omnia facta sunt; Gk. di ou ta panta egeneto).

The Son’s mission was for us humans (qui propter nos homines; Gk. ton di hēmas tous anthrōpous).

He came for our salvation (et propter nostram salutem; Gk. kai dia tēn hēmeteran soterian).

The Humbling of God to Servanthood

God the Son descended to human history (descendit). The descent from heaven (de coelis) to earth.

The Incarnation: Truly Human

For us the Son became incarnate (incarnatus; Gk. sarkōthenta).

Was conceived by the Holy Spirit (de Spiritu Sancto).

Born of the Virgin Mary (ex Maria virgine).

Was made man (homo factus est; Gk. enanthrōpēsanta).

PARTS II AND III. Our Lord’s Earthly Life—He Died for Our Sins

Our Lord’s Earthly Life (Prophetic Office)

His Suffering and Death (Priestly Office)

Jesus was crucified (crucifixus).

For us (pro nobis; Gk. huper hēmen).

Tried under Pontius Pilate (sub Pontio Pilato).

Suffered (passes; Gk. pathonta).

Died and was buried (sepultus est).

Part IV. Exalted Lord

[He descended into the abode of the dead (descendit in inferna (not in the Creed of the 150 Fathers, but appearing in the creed of Rufinus, AD 390)]. He was raised again from the dead (resurrexit; Gk. anastanta).

According to the Scriptures (secundum Scripturus).

On the third day (tertia dei).

He ascended into heaven (ascendit in coelum).

His Coming Kingdom (Regal Office)

He now sits at the right hand of the Father (sedet ad dexteram Patris).

And he shall come again (et iterum venturus est) to judge the quick and the dead (COC 2:57–58).

Why This Organizing Principle?

“Before you go forth,” wrote Augustine, “fortify yourselves with your Creed,” for it is composed of words received from “throughout the divine Scriptures,” but which “have been assembled and unified to facilitate the memory” (Augustine, The Creed 1). The creed is compact, memorizable, serving the teaching function of bringing together the heart of the matter of Scripture.

Note that this organizing principle expresses both a logical and a chronological order. It is logical in that it proceeds from Christ’s identity to his activity, from his person to his work, from his being to his doing, from who the Mediator is to what the Mediator does to benefit humanity. This Person is required for this saving act, for who else could do this work of reconciliation?

Since there can be no salvation without a Savior, there is no soteriology without Christology. For if Jesus were not truly divine Son, then his atoning action on the cross would have been insufficient—merely an example of human heroism or altruistic generosity.

The order of the creed is chronological because the story of salvation is a history. This is a basic premise of Hebraic religion. History (which declares God’s salvation) unfolds chronologically as a linear, sequential development. Consequently the study of Christ proceeds according to the order of time (chronos), within which a pivotal moment occurs that divides time—appearing at the fullness of time (kairos).

This historical sequence could be schematized as a cycle of descent ending in death, followed by ascent ending in exaltation. The descending sequence is called the humbling (lowering, lowliness, humiliation) of God, because it takes the story of the Mediator chronologically from preexistence to death, in a descending order from the highest of the high to the lowest of the low. It reveals the lowliness of God to the greatest conceivable extent. In this study we will take that descent step by step in Parts I, II, and II ahead. Part IV must be portrayed in the reverse ascending order, since it begins in the depths and moves upward toward exaltation into the reception of the Son into the heavenly kingdom; hence it is called the exaltation of the messianic king.

In this way the twofold movement of descent and ascent, the humbling and exaltation of God the Son, provides a way of organizing exceptionally diverse materials of New Testament Scripture into a single memorable confession of faith encompassed in the Nicene Creed.

The four Parts of this study may be stated concisely:

He came.

He lived.

He died.

He rose.

The first question to be faced is: Who came?