3

DIVINE SONSHIP

The confession that Jesus Christ is Son of God stands as a key confession of the primitive oral tradition, amplifying other concise confessions (“Jesus is the Christ,” “Jesus Christ is Lord”). John’s first Letter states: “If anyone acknowledges that Jesus is the Son of God, God lives in him and he in God” (1 John 4:15; Augustine, Comm. on First Epist. of John, Hom. 8.14). The 150 Fathers at Constantinople confessed the Son born of the Father by whom were all things made (COC 2: 58; 1 Cor. 8:6; SCD 13, 54, 86).

“Son of God” is concisely defined by the Russian Catechism as “the name of the second Person of the Holy Trinity in respect of his Godhead: This same Son of God was called Jesus, when he was conceived and born on earth as man; Christ is the name given him by the Prophets, while they were as yet expecting his advent upon earth” (COC 2:466).

The Title “Only Son”: What it Means

Both the Pauline term “his own Son” (Rom. 8:3), and the Johannine term “his only Son” (John 1:18) point to the unique pretemporal relation of Son to Father. The Son is unique, one and only (monogenēs, “only-begotten”) eternal Son, uncreated Son of God (Filium Dei, Creed of 150 Fathers).

This Sonship points to an eternal relationship, not to a temporal beginning point. Gregory of Nazianzus noted sharply: “Father is not a name either of an essence or of an action, most clever sirs. But it is the name of the relation in which the Father stands to the Son, and the Son to the Father” (Theol. Orat. 29.16, italics added). “One and only Son” (John 3:16, 18) indicates that Jesus is the only one of his class. The Greek term for one and only Son, monogenēs (Latin: unigenitum), came to have a pivotal function in all subsequent Christian teaching.

The One Son by Nature Distinguished from the Many Sons and Daughters by Grace

His eternal sonship is by nature, while the believer’s daughterhood or sonship in him is by grace. The daughterhood and sonship in which believers participate is not independent or autonomous, but entirely dependent upon their relation to this one and only Son of the Father. The term “one and only Son” distinguished all “holy men who are called sons of God by grace” from the one and only Son who is by nature consubstantial with the Father, in whose Sonship our sonship is hidden (Russian Catech., COC 2:467; Augustine, Trin., FC 45: 171–83; Chemnitz, TNC).

Calvin refined this distinction: “That we are sons of God is something we have not by nature but only by adoption and grace, because God gives us this status. But the Lord Jesus, who is begotten of one substance with the Father, is of one essence with the Father, and with the best of rights is called the only Son of God (Eph. 1:5; John 1:14; Heb. 1:2), since he alone is by nature his son” (Calvin, Catech. of the Church of Geneva; BOC: 18–20).

God sent his Son “that we might receive the full rights of sons” and daughters (Gal. 4:5). The mission of the Son is to bring humanity into a reconciled relation to the Father (Chrysostom, Hom. on Gal. 4). The faithful are called “into fellowship with his Son Jesus Christ our Lord” (1 Cor. 1:9). Through faith and love believers share in the life of fellowship with “the Father and with his Son, Jesus Christ” (1 John 1:3; Augustine, Comm. on First Epist. of John). “Because you are sons, God sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, the Spirit who calls out, ‘Abba, Father’” (Gal. 4:6; Marius Victorinus, Epist. to Gal. 2.4.3–5).

If the eternal Father had no eternal Son, it could not be said, as so often said in scripture:

- that God both sends and is sent;

- that God could be both lawgiver and obedient to law;

- that God could both make atonement and receive it;

- that God could both reject sin and offer sacrifice for sin;

- that God could at the same time govern all things, yet become freely self-emptied in serving love (Hilary, Trin. 9.38–42).

The Resurrection Declared What Was Prefigured in the Annunciation and Baptism

He who in due time was declared Son of God by his resurrection had been announced as Son of God at his annunciation and anointed as Son of God at his baptism.

Paul drew from a pre-Pauline oral tradition in announcing the startling subject matter of the gospel—Christ Jesus, God’s Son—“who as to his human nature was a descendent of David, and who through the Spirit of holiness was declared with power to be the Son of God [huiou theou] by his resurrection from the dead: Jesus Christ our Lord” (Rom. 1:1–4, italics added). In Jesus we meet a human being descended of David “as to his human nature,” whose hidden identity as Son of God was finally revealed in the resurrection. The resurrection was placed first in Paul’s sequence of topics, because only through that lens did the faithful rightly grasp the events that had preceded it (William of St. Thierry, Expos. Rom., CFS 27: 21–23; Luther, Comm. on Epist. to Rom: 20).

Long before the resurrection, the annunciation narrative had already signaled the identity of the coming One, according to Luke. Though his divine sonship would not be widely recognized until his resurrection, from the first announcement of the coming of Jesus, the angelic visitor indicated to Mary that “the holy one to be born will be called the Son of God” (Luke 1:35), the “Son of the Most High” (Luke 1:32; Irenaeus, Ag. Her. 3.9.1; 3.10.1).

In the narrative of Jesus’ baptism, the voice from on high declared: “You are my Son, whom I love; with whom I am well pleased” (Mark 1:11; Matt. 3:13–17; Luke 3:21–22; Lactantius, Div. Inst. 4.15). The Baptist also “gave this testimony” to the expected one who would “‘baptize with the Holy Spirit.’ I have seen and I testify that this is the Son of God” (John 1:32, 34). This did not imply an adop-tionist teaching, by which it might be assumed that prior to his baptism Jesus was not the Son of God, but was at that point adopted. Rather he was named what he always was (Hilary, Trin. VI.23–36).

Sonship and Time

In the relation of Father and Son, no notion of time appears (Augustine, Hom. on John). Jesus did not become Son at a particular stage but is eternally and pretemporally the Son, whose sonship was affirmed and celebrated at his baptism. Augustine argued that since “He is the Only-begotten Son of God, the expressions ‘has been’ and ‘will be’ cannot be employed, but only the term ‘is’, because what ‘has been’ no longer exists and what ‘will be’ does not yet exist” (Augustine, Faith and the Creed 4.6).

The Son enjoyed a pretemporal relation with the Father prior to the incarnation (Rom. 8:3; John 1:1–10; 1 John 4:9–14), a relation that time-bound mortals will never adequately fathom, but to which human speech can joyfully point. The notion of “pre”-temporal is paradoxical, because it must use a temporal prefix (“pre”) to point to that which transcends the temporal. Nothing exists “before” time except God.

Cyril of Jerusalem astutely noted that “He did not say: ‘I and the Father am one,’ but “I and the Father are one’ that we might neither separate them nor confuse the identities of Son and Father. They are one in the dignity of the Godhead, since God begot God” (Catech. Lect. 11 FC 61:226, italics added). That the Son is called “Very God of very God” means “that the Son of God is called God in the same proper sense as God the Father” (Russian Catech, COC II: 467; Council of Nicaea, SCD 54).

Son of the Father, Son of Mary

The Mission of the Son

The mission of the Son is to save humanity. “The Father has sent his Son to be the Savior of the world” (1 John 4:14). “When the time had come, God sent his Son” to “redeem those under law” (Gal. 4:4, 6). This only Son of the Father became flesh, entered history, and shared our humanity (John 1:14–18).

It was this One who suffered and died: “Although he was a son, he learned obedience from what he suffered and, once made perfect, he became the source of eternal salvation for all who obey him” (Heb. 5:8–9). His way of being a son was not a pampered, favored way, but a hard, narrow way. By this same narrow way do the faithful still enter into daughterhood and sonship, learning to trust the Father through life experiences suffered.

The Son was delivered to death, bore our sins, reconciled us to the Father, and brought us life (Rom. 5:9–11, 8:32), which is lived “by faith in the Son of God” (Gal. 2:20; Chrysostom, Hom. on Gal. II). Salvation hinges upon the fitting answer to the simple, straightforward question: “Whose son is he” (Matt. 22:41) whose narrow path led to the cross?

Whether Jesus Viewed Himself as Son of God

Did Jesus think of himself as Son of God? When tried before the Sanhedrin, charges were made to which Jesus did not reply. Put under oath (Matt. 26:63) he was asked directly the crucial question of his identity as Son: “Are you the Christ, the Son of the Blessed One?” (Mark 14:61). To make sense of this question, a premise is required: someone—either he or another—had claimed that he was the Son of God during his lifetime (Tertullian, Ag. Praxeas 16–18).

Jesus’ response before the Sanhedrin rulers, according to Mark, finally ended the suspense that had been in question during his entire earthly ministry: “I am,’ said Jesus. ‘And you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Mighty One and coming on the clouds of heaven’” (Mark 14:62). Note the shocking parallelism: Now I am being judged by you, but at some point you will be judged by the Son of Man who is now being judged. Only God exercises final judgment—hence the charge of blasphemy (Calvin, Comm. 17:255–58).

This passage reveals the intricate interweaving of the two titles “Son of Man” and “Son of God,” their affinity in the minds of the proclaiming church, and their complementarity. The Son of God “has been given authority to judge because he is the Son of Man” (John 5:27; 18:31; Tertullian, Ag. Praxeas 23).

Harnack balked. He thought that “The sentence, ‘I am the Son of God’ was not inserted in the Gospel by Jesus himself,” but constitutes “an addition to the Gospel.” Hence in his view, “The Gospel, as Jesus proclaimed it, has to do with the Father only and not with the Son” (What Is Christianity?: 92, 154). From Harnack’s complaint has emerged a whole scholarly industry—biblical historical criticism’s attempt to detach Jesus from divine sonship, a massive hundred-year enterprise that is now facing bankruptcy (Stuhlmacher, HCTIS: 61–76; Maier, EHCM: 12–26; Wink, BHT: 1–15).

It is likely that the acceptance of the title “Son of God” by Jesus has its origin and explanation not in the later memory of the disciples but in Jesus himself (Matt. 11:25f., Luke 10:21f.; Guthrie, NTT: 301–20; T. W. Manson, Teaching of Jesus: 89–115).

The divine sonship theme appeared prominently at the five most crucial moments of Jesus’ ministry: his baptism, temptation, transfiguration, crucifixion, and resurrection (Mark 1:11; 9:2–8; Matt. 3:13–17, 17:1–8; 27:40). In the temptation narrative Jesus was challenged as Son of God to perform miracles for his own benefit (Luke 4:1–13). He refused. A similar taunt was flung at his crucifixion: “Let God rescue him now if he wants him, for he said, ‘I am the Son of God’” (Matt. 27:44). Whether Jesus referred to himself as Son of God remains under debate, but these passages make it clear that Jesus was perceived by rememberers (including detractors) as having received and not disavowed the title Son of God.

The Reliability of Johannine Testimony

John’s Gospel requires special treatment on the theme of sonship, since it was for this very purpose that John wrote his Gospel—to make more explicit what had been implicit in the other Gospels—“that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God” (John 20:31: Tertullian, Ag. Praxeas 25).

If we were required for critical considerations to rule out John’s Gospel in forming our assessment of Jesus’ identity as Son of God, then the ample resources of canonical scripture would instantly become vastly skewed and off-center. Some critics have preferred to take John out of their private canon because of its presumed lateness. Hence it cannot be left to conjecture as to why classic Christian teaching regards John’s Gospel as a reliable narrative:

Technical studies have shown that John’s meticulous inclusion of specific topographical and factual details lends overall credibility to the Palestinian origin of his report (Cana, John 2:1–12; the discussions with Nicodemus, 3:1–21, and the Samaritan woman, 4; Bethesda, 5:2; Siloam, 9:7). John reveals careful knowledge of place names, customs, geographical sites, specific people and private relationships, and the precise movement of people from place to place that could hardly have been invented subsequently (or if invented, what could possibly be the purpose of such invention? R. D. Potter, Texte und Untersuchungen 73:320–37). Johannine language is closer to the Dead Sea Scrolls than the Synoptics, thus pointing to its Palestinian origin, even though the author was more likely in Ephesus when writing. The Fourth Gospel contains “evidences of a familiarity with Palestinian conditions during our Lord’s life which could not have been possessed by one who had not come in personal and contemporaneous contact with them” (Hall, DT 6:307; W. F. Albright, in W. Davies and D. Daube, Background of the NT and Its Eschatology: 170–71).

Although debates may continue as to the precise identity of its author, there can be little doubt, based on internal evidence, that the Fourth Gospel was written by one who had direct eyewitness contact with the events reported. If John was exceedingly careful in remembering details, but entirely inaccurate in reporting his major subject—Jesus as Son of God—that would constitute an implausible inconsistency rejected by widely respected scholars. J. B. Lightfoot, C. H. Dodd, C. K. Barrett, G. E. Ladd, R. E. Brown, David Wells, and other scholars have shown that John represents a reliable tradition of memory of Jesus. The Gospel shows how missionary teaching was occurring in settings far away from Palestine yet was grounded in the history of Jesus in Palestine (C. H. Dodd, Historical Tradition in the Fourth Gospel; L. Morris, Studies in the Fourth Gospel; A. J. B. Higgins, The Historicity of the Fourth Gospel; J. L. Martyn, History and Theology in the Fourth Gospel).

The tendency of some modern critics to discredit the Johannine testimony is unjustified. Its high level of spiritual discernment makes it improbable that it might have been a manipulative attempt on the part of a later writer to falsify the narrative or put words in the mouth of Jesus inaccurately or to serve partisan interests. Where the Fourth Gospel restates points made in the other Gospels, there is reason to believe that it does so more accurately, more precisely, or in more specific detail than the others (C. K. Barrett, The Gospel According to St. John; W. Sanday, Criticism of the Fourth Gospel). Attempts to discredit John’s Gospel may be based more on ideological resistance to his high appraisal of the eternal Son than any internal or external evidence. Classical Christianity has chosen to rely on the historical trustworthiness of John as equal to that of the synoptic writers.

The sonship of Jesus to the Father is at the heart of the Johannine tradition. Jesus speaks of God as Father over a hundred times in John’s Gospel. The Son’s words, accordingly, are God’s own words (John 8:26–28). “The Father loves the Son” in a special way and “shows him all he does” (John 5:20), “so that ‘all things that the Father has’ belong to the Son, not gradually accruing to him little by little, but are rather with him all together and at once” (Basil, On the Spirit 8.20). Even as he walked toward death, he understood himself to be specially and uniquely sent and loved by the Father (John 10:17; Pearson, EC I: 49–69).

His union with God was more than a diffuse sharing in God’s purpose. It was such that he was uniquely God, the Son being in the Father, and the Father in the Son (10:38; 14:10–11). What the Father intended, the Son knew; and what the Son was doing, the Father knew (John 10:15; Matt. 11:27; John 10:30; Augustine, Hom. on John, Tractate 47–48). Yet Son and Father are distinguishable. The Father sends, the Son is sent; one commands, the other obeys (John 15:10–20; Tho. Aq., ST 3 Q20).

Does the Sonship Tradition Reinforce Social Inequalities?

Rich familial images pervade early Christian teaching: God as Father sends his Son for redemption. The church as mother maternally nurtures this growth. One cannot understand this paternity without this maternity: “You are beginning to hold Him as a Father when you will be born of Mother Church” (Augustine, The Creed 1).

Modern egalitarian complaints against Christianity, leaning toward romanticist, quasi-Marxist, proletarian, and some secular feminist ideologies, are prone to turn angry and testy, claiming that there is an overemphasis upon super-and subordination and little notion of equality in Christian Scripture and tradition. The seldom mentioned, but distinctive and beautiful, contribution of Christianity to the teaching of equality is found in its teaching on the servant of God. Equality implies servanthood (Phil. 2:6–11; Epiphanius, Ancoratus 28).

We find in classic exegesis a powerful statement on equality and gentleness. In triune teaching it distinctly belongs to God to be both equal and less than himself! “It pertains to the Godhead alone not to have an unequal Son” (Council of Toledo, CF: 103). The internal logic of triune relations implies and requires that God the Son is by nature equal to the Father, while voluntarily becoming utterly responsible to the Father. Intrinsic equality becomes voluntary poverty and subordination. The formula is so simple in its profundity that it first appears innocuous or unreasonable.

God the Son, by being truly human without ceasing to be truly God, is both equal to the Father and less than the Father—equal by nature and less by volition to service. By this paradox, the usual logic of equality is turned upside down. In the Godhead all historical inequalities are finally transcended. Equality and servanthood thus belong together and cohere congruently. This we see reflected in the Symbol of Faith of the Eleventh Council of Toledo, which serves as a consensual guide to Christian reflection on equality and servanthood:

Similarly, by the fact that He is God,

He is equal to the Father;

by the fact that He is man,

He is less than the Father.

Likewise, we must believe that He is both greater

and less than Himself:

for in the form of God

the Son Himself is greater than Himself

because of the humanity which He has assumed

and to which the divinity is superior,

but in the form of the servant

He is less than Himself, that is, in His humanity

which is recognized as inferior to the divinity.

For, while by the flesh which He has assumed

He is recognized not only as

less than the Father

but also as less than Himself,

according to the divinity He is co-equal with the Father;

both He and the Father are greater than man whose nature

the person of the Son alone assumed.

Likewise, to the question whether the Son might be equal to,

and less than the Holy Spirit, as we believe Him to be

now equal to,

now less than the Father, we answer

according to the form of God He is equal to the Father

and to the Holy Spirit;

according to the form of the servant,

He is less than both the Father

and the Holy Spirit

(Eleventh Council of Toledo, CF: 170–71; indentation and italics added)

The Preincarnational Life of the Son

Without the premise of preexistence, there can be no thought of the incarnation or Christmas. The temporal birth assumed and required a pretemporal life. The existence of the Logos necessarily preceded the incarnation. If the Savior is God, then that One must be eternal God, hence must have had some form of preincarnate being prior to the incarnation in time, just as he continues in exaltation after his incarnate life (Phil. 2:6–11; Chrysostom, Hom. on Phil. 7).

The Logos that is eternal by definition must exist before time. This is hardly an optional point of Christian theology. Far from being a later development shaped by Greek philosophy, the seeds of this premise were firmly embedded in the earliest Christian preaching, for how could the Son be born in time or sent from the Father on a mission to the world if the Son had no life with the Father before the nativity? There is no “before” with him. “Begotten before. Before what, since there is no before with Him?…Do not imagine any interval or period of eternity when the Father was and the Son was not” for the Son is “always without beginning” (Augustine, The Creed 3.8). “The Sources of Time are not subject to time” (Gregory of Nazianzus, Orat. 29.3).

What is the price of the neglect of this premise? It might seem that this might be alleged to be a later or inconsequential addition to the earliest tradition. That might be plausible if this theme were not so persistent in the earliest strains of oral tradition preceding Paul, or if it were not found in all the New Testament’s major writers. Not only attested by Paul, but by Luke-Acts, Hebrews, John, James, and other New Testament writings, the eternal life of the Son of God is assumed to be antecedent to the incarnation. Lacking the premise of preexistence, the nativity narratives are rendered meaningless. If the Son came into being only at his birth, then there can be no triune God, for the Son would not be eternal, hence not God (Augustine, Hom. on John 6:60–72, Tractate 27).

If the eternal Son did not exist with the Father before his earthly ministry, then the teachings of Paul and John are drastically discredited. This is why the premise of preexistence is so insistent and pervasive in New Testament and ecumenical teaching (Pearson, EC I:195; Forsyth, PPJC: 261–90). “In the past God spoke to our forefathers through the prophets,” but “in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son” (Heb. 1:1–2). The Word of God is spoken through the life of the Son. These two recurrent terms—Word and Son—are principal titles ascribed to the pretemporal existence of the One who assumed flesh in Jesus. “He is called Son, because he is identical with the Father in essence,” and “Word, because he is related to the Father as word to mind” (Gregory of Nazianzus, Theol. Orat. 30.20).

The preexistent Logos theme has set boundaries for Christian teaching. It defends against the error that Jesus was first and foremost a good teacher whose teaching and death later caused his disciples to ascribe to him attributes of divinity. The modern expression of this is the tradition from David F. Strauss to Herbert Braun that seeks to reduce all talk of transcendence to human psychological or anthropological categories. The logic of the earliest kerygma was that God has chosen to come to humanity—not humanity to God.

Preexistence in the Pauline Tradition

Preexistence is not exclusively a Johannine idea, as is evident from its recurrent treatment in Pauline Letters (1 Cor. 8:6; 2 Cor. 8:9; Eph. 1:3–14). Paul taught preexistence in conspicuous passages. The Son was “in very nature God,” yet “did not consider equality with God something to be grasped” because he already shared fully in the divine life and was willing to become obedient unto death in order that the divine life be manifested to humanity in servant form (Phil. 2:5–11; Gregory of Nyssa, Ag. Eunomius 3.2.147). Not only is the Son “before all things,” but also “in him all things hold together” (Col. 1:16; Chrysostom, Hom. on Col. 3). The Son who is before all things is coeternal with the Father, hence nothing less than God (Hilary, Trin. 12.35–43; BOC: 577). It was through the resurrection that the primitive Christian community came to grasp and confess that the living Lord is eternal Son (Rom. 1:1–4).

“When the time had fully come, God sent his son.” Only one who already exists could be sent. This one was sent to be “born of a woman, born under law, that we might receive the full rights of sons. Because you are sons, God sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, the Spirit who calls out, ‘Abba, Father’” (Gal. 4:4–5, italics added). The triune premise saturates this Pauline passage. The speech of the Father through the Son is communicated through the Spirit to enable the sonship and daughterhood of the faithful.

Allusions to the preexistence of Christ appear embedded in the earliest oral traditions antedating Paul’s Letters (Phil. 2:6–11; 1 Cor. 15:47; Col. 1:17; 1 Tim. 3:16; F. Craddock, The Pre-Existence of Christ). They do not display any indications that they might have been appended later. They are attended with no speculative details or mythic ornamentations, but rather presented as intrinsic to the faith presumably shared by all who proclaim the gospel of God. Here form criticism may be correctly put to a service quite opposite from that assumed by many form critics, since they point toward establishing an early date for the preexistence theme (Taylor, PC: 62–78; A. M. Hunter, Paul and His Predecessors: 40–44; C. F. D. Moule, Colossians and Philemon, CGTC: 58).

Christ as Word of God—Logos Christology

The main stem of New Testament usage of Christ as Word (Logos) comes not from Greek philosophy but from the ancient Hebraic dabar Yahweh (“Word of God”) by which the world was made and the prophets inspired (Manson, Studies in the Gospels and Epistles: 118). Bultmann argued for the Hellenistic origin of the Logos language of the New Testament, but the more probable roots are Semitic (Cullmann, CNT: 249). John 1:1–3 is best seen in recollection of Genesis 1:1 (Ephrem the Syrian, Comm. on Tatian’s Diatess. 16.27; Augustine, Trin. 15.13).

John’s Gospel speaks of the Logos as active agent through whom God created the world (“through whom all things were made,” John 1:3). This is consistent with Paul’s language, that all things come from God the Father through Christ the Son: “For us there is one God, the Father, from whom all things came and for whom we live; and there is but one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom all things came and through whom we live” (1 Cor. 8:6, italics added; Chrysostom, Hom. on First Cor. 20.6; Ambrose, On the Holy Spirit 13.132). It is this eternal Word (logos) that becomes flesh (sarx), contrary to common Hellenistic assumptions and expectations. If the preaching of the early Christian kerygma had been seeking to accommodate to a Hellenistic audience, it would certainly not begin by saying: Logos becomes flesh. It is this enfleshed Logos, the Son, through whom God the Father is revealed (John 1:17–18; Athanasius, Ag. Arians, 2.18.24–36; Newman, Ari.: 169).

Pauline and Johannine views are far less in tension on preexistence than some have imagined. If preexistence receives intermittent but crucial reference in Paul, it receives persistent and decisive reference in John. The eternal Logos, whose glory the disciples beheld in Jesus Christ, not only appeared in time but also, according to John’s Gospel, was “in the beginning.” The Logos was God and was with God in the beginning (John 1:1–2), through whom “all things were made; without him nothing was made that has been made” (1:3; Didymus the Blind, Comm. on 1 John 1.1).

The preexistence theme is found in the Markan report of Jesus’ own teaching of himself as heavenly Son of Man come down from above (Mark 5:7; 9:7–31; 13:26; 14:61–62). This is consistent with his saying in the Fourth Gospel: “Before Abraham was born, I am” (John 8:58; Gregory I, Forty Gospel Homilies 16). Preexistence is assumed in the prayer of Jesus who, when his “time had come,” prayed: “And now, Father, glorify me in your presence with the glory I had with you before the world began” (John 17:5). The Son was glorified in the presence of the Father with a glory that was voluntarily given up in his earthly life. In humbling himself, the preexistent Logos constrained his divine glory with the Father to take on the form of a servant.

Only he existed before he was born. For the Son has two natures: “He was God before all ages; he is man in this age of ours” (Augustine, Enchiridion 10.35). “He was not first God without a Son [and] afterwards in time became a Father; but He has the Son eternally, having begot Him not as men beget men, but as He Himself alone knows” (Cyril of Jerusalem, Catech. 11). Hence the views of Paul of Samosata, Photinus, and Priscillian were rejected by orthodox exegesis insofar as they taught that the Son “did not exist before He was born” (John III, Council of Braga, SCD 233: 93).

The Humbling of God to Servanthood

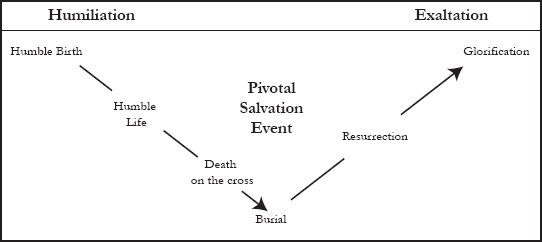

Humiliation and Exaltation

The humbling of the Son to servanthood is a major dogmatic grouping of topics that includes all Christological issues between his incarnation and his burial. It is distinguished from the raising of the Son to governance, which includes all topics from his resurrection to final judgment (Hilary, Trin. 9–11). Within this broad frame, Christ’s mediatorial work is seen in three offices that correlate generally with this chronological progression: prophetic teaching, priestly sacrifice, and regal governance, schematized as follows, as a map for the discussion ahead:

Stages of Descent and Ascent

Three Messianic Offices Linked with these Stages: | |||||

|

Prophetic |

Priestly |

End-time | |||

|

Teaching |

Sacrifice |

Governance |

The prophetic office is undertaken primarily during the descent, the period of humiliation. The priestly sacrifice focuses upon the pivotal event—the death of Christ—marking the end of God’s humbling and the reversal leading to exaltation. Fulfillment of the regal office is primarily associated with exaltation, ascent to the Father. The cross marks the boundary between descent and ascent of the Son. The salvation event had been prophetically promised to occur through suffering and death (Isa. 53:4–9).

Each step of Jesus’ life descended toward his death, followed by his further descent into the grave. The sacrificial death of the Savior marked the clear line between the two overarching phases of the Son’s ministry, in which divine powers and attributes were at first voluntarily constrained, then exercised (Chrysostom, Hom. on Phil. 7,8).

The humiliation of the eternal Son was marked by a temporary but not absolute cessation of the independent exercise of divine powers. This was chosen in order to show forth the voluntary acceptance of humanity, birth, finitude, suffering, and finally death and burial (Phil. 2:6–8). His exaltation was marked by a full resumption of the exercise of divine powers (Phil. 2:9–11). The Son’s exaltation confirmed the hidden meaning of his humiliation (Gregory of Nazianzus, Orat. 87).

The Humbling of the Eternal Son Under Limits of Time

The humbling of God was not an enforced humbling, but an elected, voluntary humbling (Theodoret, Epist. to Phil. 2.6.7). The humiliation (tapeinōsis) was temporary, lasting from birth to death, or more precisely from the Son’s first moment of conception to his last moment in the grave. The phase of exaltation begins with his resurrection and continues to the last day.

The eternal Son humbled himself first to birth, then to death, and only then was exalted to return to glory with the Father. The contrast between the two overarching phases of mediatorial ministry is based upon contrasting phrases of Philippians 2: he “made himself nothing” (verse 7), and “Therefore God exalted him” (9). The sequence of conditions was an original glory followed by suffering servant life followed once again by glory.

The humbling motif is found in the Nicene Creed in the phrase: “He came down from heaven” (descendit de coelis; Creed of 150 Fathers, COC 2:58). The descent theme is presupposed in the titles Son of God, Son of Man, Logos, and Lord, for how could the eternal Son become incarnate as a child without “coming down”—a spatial metaphor of descent, of self-chosen lowering of power, and of taking upon himself all human limitations including death? (Origen, Comm. on John 20.18; Doc. Vat. II: 563–67).

What is meant by the phrase, he “made himself nothing” (Phil. 2:7; Gk. heauton ekenosen; Lat. semet ipsum exinanivit)? This is sometimes referred to as the renunciation (or exiniation) of the Son, whose earthly ministry was characterized by self-emptying (kenosis) or voluntary abnegation of the divine glory (Hilary, Trin. 9.48). Not until the resurrection did he resume the full exercise of divine dominion.

The Disavowal of Uninterrupted Exercise of Sovereign Powers

This voluntary renunciation consisted essentially in the disavowal or partial and temporary abdication of full and uninterrupted exercise of divine powers, while the Son accepted the incarnate life and assumed the form of a servant (Chrysostom, Hom. on Phil. VI; Newman, Ari.: 163–66). It is this self-giving, serving love that Paul was commending as a primary pattern of human behavior to the Philippians.

This involved the temporary obscuring of the divine sonship to human eyes, being hidden in the flesh of humanity (Cyril of Alexandria, Third Letter to Nestorius). “He has hidden His majesty in humanity, does not appear with lightning, thunder, or angels, but as one born of a poor virgin and speaking with men of the forgiveness of sins” (Luther, Serm. on John 4, WLS I: 154).

The metaphor of voluntary emptying should not be confused with emptiness. Embedded in the metaphor is a paradox, for when one cup is emptied into another, the other becomes full. The self-emptying of the Logos is the filling of the incarnate Son, for in emptying himself, God reveals himself as enfleshed, filling a human body with his fullness (Gregory of Elvira, On the Faith 88,89).

During his saving mission, the Son “through the eternal Spirit offered himself unblemished to God” (Heb. 9:14). While engaged in his earthly ministry, “God gives the Spirit without limit” to the One sent by the Father (John 3:34–35; Chrysostom, Hom. on John 30.2; Augustine, Hom. on John 14). The humbling of the Son ceased when, upon accomplishing this mission, the Holy Spirit was given to the church as the Son ascended to the Father.

The triune premise is essential for understanding of the descent and ascent motifs. It was not the Godhead that became incarnate, but one of the persons of the Godhead. The Godhead as such was not humbled or lowered, but the one person of the Son embracing two natures, wherein the human nature was humbled. Hence it is said that the subject of the humiliation is the human nature, unconfusedly united with the divine nature, which “neither died nor was crucified” (Hollaz, ETA: 767; Schmid, DT: 381).

Form of God, Form of a Servant

The locus classicus text of this teaching is Philippians 2:5–11. The context in which this pivotal passage occurs is an appeal to follow Christ’s way of lowliness. Paul had just instructed the Philippians to “do nothing out of selfish ambition or vain conceit, but in humility consider others better than yourselves. Each of you should look not only to your own interests, but also to the interests of others” (Phil. 2:3–4). This way of lowliness was pioneered by Christ himself: “Let this mind be in you, which was also in Christ Jesus” (v. 5; Mark the Ascetic, Letter to Nicolas, Philokal. 1:155–56). What follows is quite likely an early Christian hymn or hymnic fragment, used or adapted by Paul (ACCS NT 8:236–254).

In the Form of God: Morphē Theou

The One who became Servant was the very One who “being in the very nature God [morphē Theou]” (Phil. 2:6), namely the preexistent Logos who subsisted in the form of God before the incarnation, enjoyed an existence equal to that of God (Council of Ephesus, SCD 118). The divine nature was his from the beginning.

The same theme recurs in Colossians: “There is but one Lord, Jesus Christ, through whom all things came, and through whom we live” (1 Cor. 8:6); “by him all things were created” (Col. 1:15). The premise of this language: Christ pretemporally existed in the form and glory of God. He “did not consider equality with God something to be grasped” (forcibly retained, Phil. 2:6).

By contrast, recall that Adam’s disobedience had been a presumptuous grasping for equality with God. Christ did not grasp self-assertively at the divine majesty which he already possessed (Hilary, Trin. 12.6).

He Made Himself Nothing

He voluntarily became lowly (heauton ekenosen, “He emptied himself,” Phil. 2:7). He did not inordinately claim the glory he rightly had. He made no display of it. The Son temporarily gave up the independent exercise of divine attributes and powers that manifested his equality with God. The text does not focus specifically upon what was emptied, but rather upon what the self-emptying called forth—the servant life. Kenosis did not extinguish the Logos, but the Logos became supremely self-expressed and incarnately embodied in the flesh.

Taking the Form of a Servant

In taking “the form of a servant [morphen doulou]” (Phil. 2:7), the contrast is sharpened between (a) the eternal One in the form of God who (b) voluntarily takes a constricted and limited temporal form as if slave. He came among us “as one who serves” (Luke 22:27), symbolized by his washing the feet of his disciples (John 13:1–20; Hilary, Trin. 11.13–15). Augustine warned against misreading this lowliness: “The form of a servant was so taken that the form of God was not lost, since both in the form of a servant and in the form of God He himself is the same only-begotten Son of God the Father, in the form of God equal to the Father, in the form of a servant the Mediator between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (Augustine, Trin. 1.7; Enchiridion 8.35). A brilliant analysis of this text is found in Hilary: “The emptying of the form is not the destruction of the nature. He who empties Himself is not wanting in His own nature. He who receives remains…. No destruction takes place so that He ceases to exist when He empties Himself or does not exist when He receives. Hence, the emptying brings it about that the form of a slave appears, but not that the Christ who was in the form of God does not continue to be Christ, since it is only Christ who has received the form of a slave” (On the Trinity 9.44).

Agreeably Leo thought the lowering to be necessary to the mediatorial role: “In what way could He properly fulfill His mediation, unless He who in the form of God was equal to the Father, were a sharer of our nature also in the form of a slave; so that the one new Man might effect a renewal of the old; and the bond of death fastened on us by one man’s wrong-doing might be loosened by the death of the one Man who alone owed nothing to death” (Letters, 124.3).

Made in Human Likeness

“Being made in human likeness” (homoioma, Phil. 2:7), being born, being under the law, he lived in poverty. The Son of God became that very kind of servant that corresponds with the conditions of human finitude. He lived in time and space under conditions that involved suffering, and death. It is not merely that the Son became a man. The emphasis is rather placed upon the comparison between the life of God and the life of humanity, the ordinary human life seen from the perspective of one who has descended from on high, from the most exalted state of glory. From that state he entered into the disadvantaged life of the poor, the neglected, those bound in rough circumstances, the hidden sufferers. In short, he became a slave (Phil. 2.7b; Leo I, Epistle 28 to Flavian 3).

The conditions common to humanity included physical development (being born and passing through stages of growth), intellectual development (learning as humans learn), and even moral development (submitting to parents and to the law), within a distinct historical context, under a particular political regime, of a particular ethnicity, and in a particular family. “His experience was that of every other man, eating, drinking, sleeping, waking, walking, standing, hungering, thirsting, shivering, sweating, fatigued, working, clothing Himself, sheltered in a house, praying—all things just as others” (Luther, in SCF: 144).

“In him God becomes oppressed man” (Cone, BTL: 215; Boff, LibT.: 60–61). “Down, down, says Christ; you shall find Me in the poor; you are rising too high if you do not look for Me there” (Luther, Serm. on Matt. 22:34–46). Being God he was found in human form, yet analogous to a human condition of the lowliest sort imaginable—as if a slave.

He Humbled Himself and Became Obedient unto Death

Though more than human, he was willing to become the least among humanity, despised and rejected (Julia of Norwich, “The Homeliness of God,” IAIA: 89). This humiliation extended over the whole of his earthly life.

The cross cast its shadow upon every step of his way from his baptism to his death (Barth, CD; 4/4: 52–67). He “became obedient to death” (Phil. 2:8).

“Although he was a son, he learned obedience from what he suffered” (Heb. 5:8). In his active obedience he chose to fulfill the obligation of the law; in his passive obedience he endured the penalty of human sin. Hence through the active and passive “obedience of the one man the many will be made righteous” (Rom. 5:19).

The humbling of the Son ends in death by crucifixion, “rectifying that disobedience which had occurred by reason of a tree, through that obedience which was [wrought out] upon the tree [of the cross]” (Irenaeus, Ag. Her. 5.16.3). In this disgraceful way—“even death on a cross” (Phil. 2:8)—he became “a curse for us” (Gal. 3:13). Such was, in brief, the humiliating schema (Phil. 2:7, “way of life”) accepted by the Son.

Why was this necessary to the divine plan? “He humbled himself, being made obedient even unto death, even death on a cross, so that none of us, though being able to face death without fear, might shrink from any kind of death that humans beings regard as a great disgrace” (Augustine, On Faith and the Creed 11). From his death we take hope. From his slavery we derive courage amid our analogous forms of limitation and suffering.

Voluntary Obedience of the Son to the Father

The notion of voluntary subordination appears in the sayings of Jesus: as enfleshed Son he wills to do nothing by himself, acknowledging that the Father is greater than he (John 5:30; 10:15, 30; 14:28; Matt. 11:27; Titus 2:13; 1 John 5:7).

To be temporarily subordinated within the conditions of time means to stand voluntarily in a lower class or order or rank. The subordination of which Paul spoke in Philippians 2:5–8 was a temporary one that ended when Jesus was exalted to the glory of the kingdom.

The peculiar heterodox view called “subordinationism” overextends this orthodox confession by arguing that the Son is not just temporally but eternally and by nature unequal to the Father (rejected by the Councils of Nicaea and Constantinople—a tendency found in Sabellianism, Arianism, and Monarchianism). Any subordinationism that fails to recognize Christ’s return to equality with the Father in glory has not been ecumenically received. Instead, the temporal subordination freely chosen by the Son demonstrated his obedience to the Father in his mission to fallen human history.

The Son, Not the Godhead, Was Humbled

The triune premise must be held firmly in place for such language to make sense. It speaks not of the temporary subordination of one divine nature to another, but of the voluntary, temporary subordination of the will of the Son to the Father, of one divine person to another on behalf of his mission to bring salvation to humanity (Eleventh Council of Toledo, CF: 170; see also SCD 284). It was the Son and not the Godhead that was humbled.

Amid the incarnate humbling of God, “so far as He is God, He and the Father are one; so far as He is man, the Father is greater than He,” and in this paradoxical way, “He was both made less and remained equal” (Augustine, Enchiridion 35). In making for himself no reputation and taking the form of a servant, he did not lose or diminish the form of God (BOC: 602–605).

This irony was given powerful ecumenical expression by the Eleventh Council of Toledo: “for in the form of God even the Son Himself is greater than Himself on account of the humanity He assumed, than which the divinity is greater; in the form, however, of a servant He is less than Himself, that is, in His humanity” (SCD 285; BOC: 602–604).

The Consequent Moral Imperative for Faith: Voluntary Servanthood

At the outset of this passage Paul was calling upon the Philippians to follow Christ’s example of lowliness of mind. His object is to elicit among the Philippians a similar attitude of self-submission, hoping that they would walk in humility, considering others better than themselves (Phil. 2:3)—that is what originally elicited Paul’s recollection and insertion of the primitive Christic hymn received from the oral tradition. Similarly you are not to grasp at equality with your neighbor but to choose the form of a servant in all dealings (Francis of Assisi, The Admonitions, CWS: 25–29; Augustine, Since God Has Made Everything, Why Did He Not Make Everything Equal? EDQ 41).

The humbling of the Son is not simply a single event of the birth narrative by itself. Rather, having been born into the world, the Son grew to maturity and had to choose again and again the way of the humble One, every moment of his life, until such choosing ended in death (John of Damascus, OF 3.21–29). All this was done willingly for human benefit. The narrative of Jesus’ earthly life reveals an ongoing ethical dimension in the humbling of God that awaits event after event to unfold in its own characteristic way of life: washing feet, reaching out for the sick and neglected, identifying with sinners, living without material comforts, dying on a cross.

His poverty consisted in the self-renunciation by which he assumed servant form—he was born in a stable, remained poor throughout his life, worked with his hands in common labor, was without a home of his own, and finally in his crucifixion was stripped of his robe and laid in the grave of another—all signs of poverty, of complete and willing lack of worldly resources. This poverty has made redeemed humanity rich by enabling persons to share in his glory by faith (Francis of Assisi, Admonitions, CWS: 32).

By his death he purchased life. By his divestiture we gain our inheritance. By his payment, we receive our passage (viaticum) to the eternal city (Gregory Thaumaturgus, Four Hom. 1; Chrysostom, Hom on 2 Cor. 19; Schmid, DT: 385). “Though he was rich, yet for your sakes, he became poor, so that you through his poverty might become rich” (2 Cor. 8:9).

Reprise: The Descending Sequence of Downward Steps of the Son’s Humbling

The humbling of the eternal Son proceeded in a long sequence of ever-lowering stages culminating in death and burial. Each step is an historical event told in the Gospels as a real and true narrative of a fully human life. Taken together, key events of the humiliation of the Son reported in Scripture are pictured as this poignant sequence of ever-lowering steps:

Being in the very nature God

He does not grasp for the equality with God due him

He empties himself

He voluntarily gives up unbroken independent exercise of the divine attributes

He is conceived by the Holy Spirit

He is born of a poor virgin in a humble manger

He was born a Jew, a son of the law

He was made one gender on behalf of two, a man, born of a woman

He willingly took the form of a servant

He first became a child

He become subject to human growth and development

He was circumcised signifying subjection to law though he was Giver of the law

He was made like his brothers in every way that he might make atonement

He humbled himself

He became obedient

He became voluntarily subject to instruction by parents

He worked in economic subjection lacking property

He was a common laborer in a manual occupation

He voluntarily subjected himself to the teachers of the law

He faced all the ordinary discomforts of human finitude

He took up our human infirmities

He was despised and rejected by men

He endured the reproaches and ill-treatment by others

He was a man of sorrows, familiar with grief

He faced suffering of body, mind, and spirit

He endured political subjection to unjust political authority

He became obedient, even unto death

Even the death of the cross

He experienced the abandonment of his followers

He became a curse for us, dying “outside the camp”

He was buried in a borrowed grave

He descended into the nether world to preach to the captives

Each step descended further than the previous one. It was an ever narrowing descent from heaven to hell. In sum he as Son of God humbled himself in every conceivable way. He became obedient to reveal the true nature of humanity amid the dreadful conditions of the history of sin. In doing so he was prepared to serve as the representative of humanity in the Father’s presence, presenting to God the perfect obedience due from humanity (Rom. 6:14; 13:10).

What the law was powerless to do “God did by sending his own Son in the likeness of sinful man to be a sin offering” (Rom. 8:3). “God made him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Cor. 5:21; Gal. 3:13; 4:4–5; Augustine, On Romans 48).

Nowhere in nature is the heart of God so fully revealed as it is in the history of Jesus: “God’s transcendent power is not so much displayed in the vastness of the heavens, or the luster of the stars, or the orderly arrangement of the universe or his perpetual oversight of it, as in his condescension to our weak nature,” wrote Gregory of Nyssa. “We marvel at the way the Godhead was entwined in human nature and, while becoming man, did not cease to be God” (ARI 24).

The Hidden Majesty: The Obscuration of the Divine

The divine humiliation was not an impoverishment of God but an incomparable expression of the empathic descent of divine love (Calvin, Inst., 2.13.3–4). God never did anything in history more revealing of the divine character than to become incarnate and die. By his coming the poor were blessed, the hungry satisfied, weeping was brought to laughter, the excluded embraced, and the reviled welcomed (Luke 6:20–23).

The earthly ministry of the Son was not first to reveal the divinity of the Son, but rather to obscure it so that the mission might be fully accomplished through his suffering and death for all (Hilary, Trin. 9.6). The divinity of the Son was eclipsed for a season only to more fully manifest its glory in due time through the resurrection of the flesh. His majesty and deity became most clear through this unique descent.

God the Son assumed human nature for the very purpose that he might experience this humiliation of his human nature on behalf of the redemption of humanity (Council of Ephesus). In this humbling, the divine nature of his person was concealed, not in the sense of being deceptively disguised, but under the assumed servant form (morphē doulou) it was simply unrecognizable to sons and daughters of Adam and Eve drenched in a history of sin.

The Voluntary Restraint of Independent Exercise of Divine Attributes

The nature of God did not change in the incarnation. Rather it was precisely through lowliness that the Servant-caregiver was revealed and became knowable in history. He who is the “same yesterday and today and forever” (Heb. 13:8) became formed in our likeness without ceasing to be unchanging God. His divinity was not reduced, retracted, relinquished, or suppressed, but enhanced, set forth, offered, and expressed in this particular manner: humbly enfleshed. “He withdrew His power from its normal activity, so that having been humiliated He might also appear to be made infirm by the nonuse of His power…. Though He retained His power, He was seen as a man, so that the power would not be manifest in Him” (Ambrose, Comm. on Phil. 2, in Chemnitz, TNC: 493).

These are the elements that make the central mystery of the incarnation unfathomable to human egocentricity, yet transparent to faith. This humbling remains the central datum of Christian proclamation and experience. While lying in the cradle and dying on the cross, he did not cease to be the One in whom “all things hold together” (Col. 1:19), in whom the fullness of the Godhead was dwelling bodily (Col. 2:9).

In his temporal lowliness the Son “abstains from the full use of the divine attributes communicated in the personal union” (Jacobs, SCF: 145). It is as if the heir of a vast estate may have a great inheritance left to him, yet in his minority he may have only that use of it that is permitted by his guardian.

Classic Christianity was careful to define that he resigned “not the possession, nor yet entirely the use, but rather the independent exercise, of the divine attributes” (Strong, Syst. Theol.: 703). On certain occasions, on behalf of his mission, he does not abstain from full use but rather exercises divine attributes (as in miracles). He could have exercised this power that was temporarily and voluntarily surrendered: “Do you think I cannot call on my Father, and he will at once put at my disposal more than twelve legions of angels? But how then would the Scriptures be fulfilled that say it must happen in this way?” (Matt. 26:53–54; Chrysostom, Hom. on Matt. 84).

Gregory of Nazianzus cautiously taught with measured restraint and discrimination: “What is lofty you are to apply to the Godhead and to that nature in him which is superior to sufferings and incorporeal; but all that is lowly to the composite condition of him who for your sakes made himself of no reputation and was incarnate” (Orat. 19.18).

Note that the relational divine attributes of holiness, love, and justice are exercised during his earthly ministry, but those pre-relational (prior to creation) divine attributes (aseity with unlimited power, knowledge, and presence) are voluntarily restrained.

Note also the irony: The hidden majesty wills to become visible, comprehensible, and existent in time, yet in a lowly way. “Invisible in His nature, He became visible in ours; surpassing comprehension, He has wished to be comprehended; remaining prior to time, He began to exist in time. The Lord of all things hid his immeasurable majesty to take on the form of a servant” (Leo 1, Letter to Flavian). Kierkegaard chose a parabolic form by which to speak of this obscuration in his unforgettable parable of the king and the maiden (Phil. Frag: 31–43).

If constantly exercised, the divine omnipotence could have exempted Jesus from suffering for our sins, but this would have run counter to the purpose of his mission. Rather, he was willing to lay down his life, reminding his hearers that “No one takes it from me, but I lay it down of my own accord. I have authority to lay it down and authority to take it up again” (John 10:18; Athanasius, Ag. Arians 3.29.57).

The Omniscience of the Son Voluntarily Constrained

The New Testament picture of the Omniscience of the Son is complex: in some passages he knows what is going on in the minds of others and knows future events; in other passages he expresses surprise at learning something by observation or he professes ignorance and asks questions that assume he did not know the answer (Athanasius, Four Discourses Ag. Arians 1.11; J. S. Lawton, Conflict in Christology; Taylor, PC: 286–306). What is the difference? In one sentence he is viewed from the point of view of his deity; in another from the point of his humanity.

This troublesome point is greatly illumined by the triune premise, and confusing without it: the divine Logos eternally experiences full awareness of the cosmos, yet as incarnate Logos united to Christ’s humanity he has become voluntarily subjected to human limitations, ignorance, weakness, temptation, suffering, and death. As eternal Son he is equal with God in knowing and foreknowing, but in the mystery of his humiliation he is servant, obedient, willing to be vulnerable to time and finitude. As conceived in the womb, as born of Mary, as child of Joseph, the eternal Logos constrained or temporarily abnegated the full and independent exercise of eternal foreknowing, so as to become a little child (Gregory of Nazianzus, Fourth Theol. Orat.). Hence the paradox: unless we become as little children (as did the eternal Son) we will not grasp the meaning of God’s coming governance (John of Damascus, OF 3.22).

Chrysostom offered a compassionate reason why the saying that the Son “knows not the day or hour” was providentially given for the good of the disciples: to diminish anxiety, for if everyone “knew when they were to die, they would surely strive earnestly at that hour” (Chrysostom, Hom. on St. Matt. 77.1). “Since He was made man, He is not ashamed, because of the flesh which is ignorant, to say ‘I know not,’ that He may show that knowing as God, He is but ignorant according to the flesh” (Athanasius, Four Discourses Ag. Arians 3.43). The reason he assumed “an ignorant and servile nature,” was “because man’s nature…does not have knowledge of future events” (John of Damascus, OF, FC 37:324–25). Thus it is said that ignorance was assumed economically by the Lord (Athanasius, Four Discourses Ag. Arians 1.11, 3.28; Newman, Athanasius 2:161–72). So in his human nature he voluntarily chose to remain ignorant of the day on which the final judgment would occur (Matt. 24:36). “No one knows about that day or hour, not even the angels in heaven, nor the Son, but only the Father” (Mark 13:32).

When the Son of God took upon himself the weakness of humanity, he did not relinquish the strength of God.

Mild He lays His glory by,

Born that man no more may die,

Born to raise the sons of earth,

Born to give them second birth.

C. Wesley, “Hark the Herald Angels Sing”