CHAPTER 4

Process-Oriented Architecture (POA)

Process Architecture is probably the least understood aspect of Process Improvement. However, the payoffs from a well-designed and well-managed architectural framework are enormous. Since processes adapt and change over time and are required to respond differently to varying environmental situations and strategies, this chapter provides an architectural model for planning, designing, and evaluating proposed changes in an organization’s operating environment. The Process-Oriented Architecture (POA) approach is concerned with planning and controlling all aspects of process creation, improvement, and retirement within an organization. The development of an effective architecture framework to manage process-related changes is key to the success of any process-focused organization. Furthermore, a truly effective POA coordinates efforts across department boundaries to ensure effective and cost-conscious improvement efforts throughout all areas of an enterprise. As Process Improvement is not a one-time effort, processes need to continuously adapt and respond to changes in a company’s environment, strategy, customer demands, business problems, and opportunities. The POA guides professionals as they propose changes to processes and related process components to respond to those events.

This chapter is organized around the following knowledge areas:

• Enterprise Architecture defined: What is the definition of Enterprise Architecture and how is Process Architecture related?

• POA defined: What is POA and how does it affect a company’s Process Improvement efforts?

• Core principles of POA: What are the driving principles behind a POA approach?

• Benefits of POA: What are the key benefits to introducing and implementing a POA Framework?

• POA Road Map: What are the key POA components and how do they assist with managing a company’s Process Improvement efforts?

Enterprise Architecture Defined

As business product and service cycles continue to change more and more rapidly, only flexible processes and maneuverable technologies can enable organizations to make the commitments required to continuously adapt and meet customers’ needs. Enterprise architecture is the act of translating business vision and strategy into an effective enterprise change by creating, communicating, and improving the key requirements, principles, and models that describe the enterprise’s current operations and enable its evolution. It is, first and foremost, an architecture approach used to describe the overall structure of an enterprise or a business unit. Second, it is about transforming a business and assisting organizations in making better decisions. This is accomplished when an organization gains an understanding of how complex their structures and processes are and ensures that proper business architecture and change management principles exist. Primarily, Enterprise Architecture seeks to model the relationships between the business, its processes, and any related components in such a way that key dependencies and redundancies from the organization’s underlying operations are exposed.

The term enterprise is used because it is generally applicable in many circumstances including

• An entire business or corporation

• A subset of a larger enterprise such as a department

• A conglomerate of several organizations, such as a joint venture or partnership

The term enterprise in the context of Process Improvement includes the entire complex, sociotechnical system within an organization including

• People

• Information

• Technology

• Processes

NOTE A common misconstruction is the notion that Business or Process Architecture is different than Enterprise Architecture, when, in fact, Enterprise Architecture is applicable to the entire organization including business, workforce, information, technology, and environmental perspectives. The belief is that Process Improvement professionals lead all process design and improvement activities in a way that encompasses all organizational viewpoints. At times, practitioners may focus more heavily upon one viewpoint or another, but they always link the interdependencies and interrelationships of these viewpoints to the business context and its temporal states (past, current, transitional, optional future, future, and retired).

Process-Oriented Architecture Defined

Process-Oriented Architecture (POA) describes the philosophical approach to process business architecture, development, and management. It is a framework that contains a set of core elements, such as operating principles, benefits, deployment activities, and various related components, that are used to design and develop processes that are interoperable and reusable.

It is a method of Enterprise Architecture that focuses on the relationships of all structures, processes, activities, information, people, goals, and other resources of an organization including any technical structures and processes as well as business structures and processes. Process Improvement practitioners can use the POA to build all-encompassing Process Ecosystems, which demonstrate how processes, systems, and other process elements are aligned, and to assist with facilitating and expediting Process Improvement efforts throughout all phases of development.

The POA also oversees the maintenance of an organization’s processes or capabilities and ensures that it depicts an organization both as it is today and as it is envisioned in the future. This includes both business-oriented perspectives and technical perspectives. In many ways, the POA serves as a communication bridge among senior business leaders, business operators, and Process Improvement professionals. Having this bridge ensures that all process-related improvements are coordinated and managed with an end-to-end perspective in mind rather than a traditional individualistic approach.

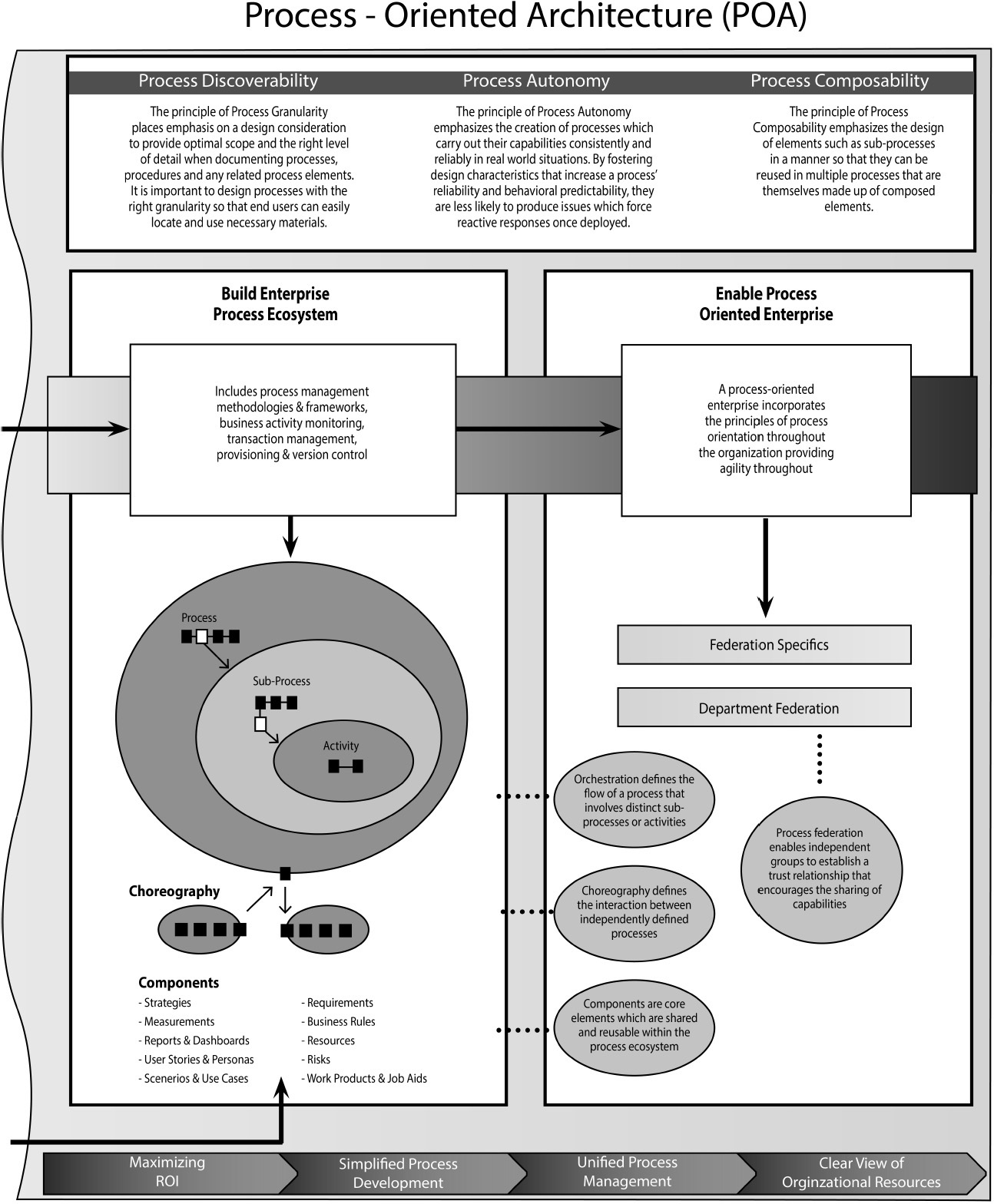

An effective POA is considered the foundation of process-focused organizations and enables enterprise visibility, alignment, and scalability. The diagram shown in Figure 4-1 illustrates the POA construct. In it, the linkage of processes to shared and reusable elements drives understanding of cause-and-effect relationships within an organization’s entire Process Ecosystem, enabling better decision-making as processes are created or changed.

FIGURE 4-1 Process-Oriented Architecture Construct

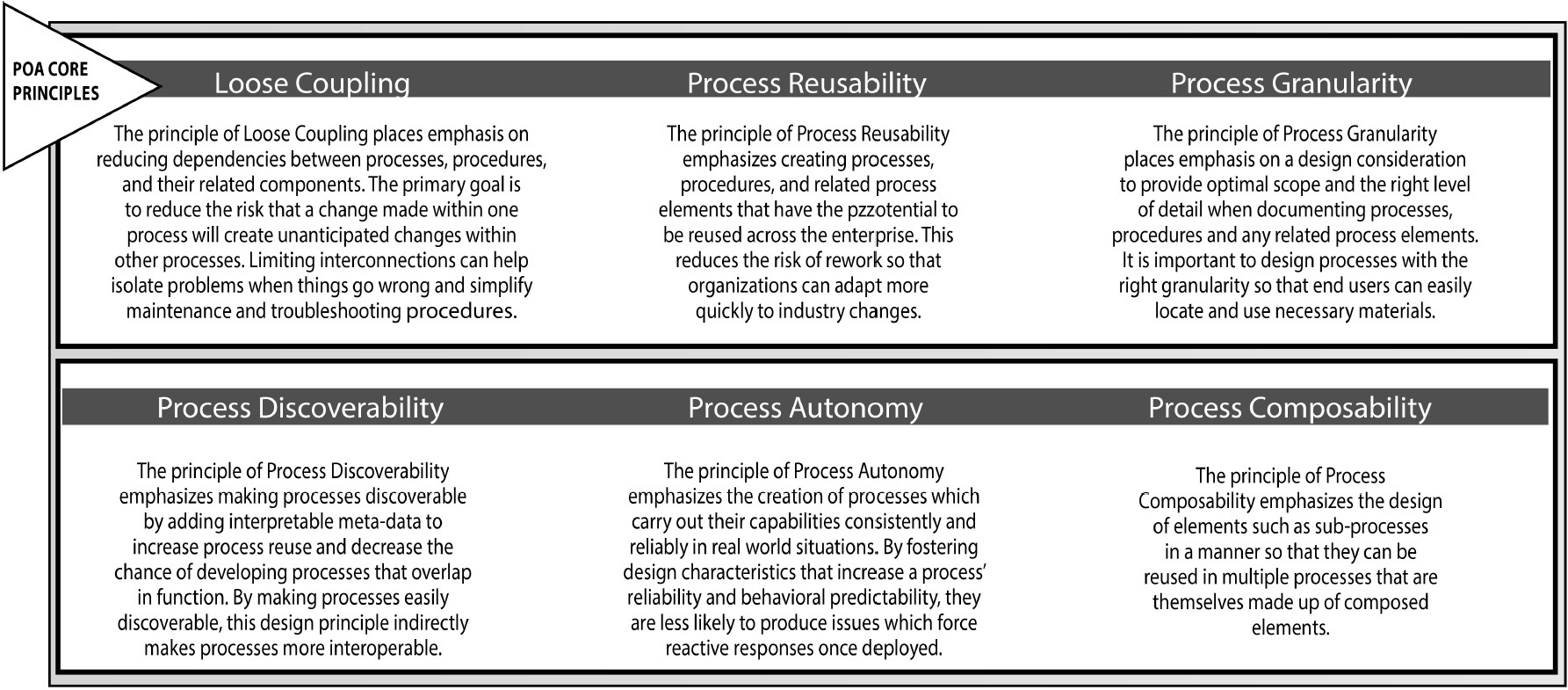

Core Principles of Process-Oriented Architecture

The Process-Oriented Architecture approach uses several architectural guiding principles to construct processes that business users can dynamically combine and compose into Process Ecosystems that meet continuously evolving and changing business requirements. The following guiding principles define the ground rules for development, maintenance, and usage of the POA to build Enterprise Process Ecosystems or business landscapes:

• Loose Coupling: This places emphasis on reducing dependencies among processes, procedures, and their related components. The primary goal is to reduce the risk that a change made within one process will create unanticipated changes within other processes. Limiting interconnections can help isolate problems when things go wrong and simplify maintenance and troubleshooting procedures.

• Process Reusability: This emphasizes the creation of processes, procedures, and related process elements that have the potential to be reused across the enterprise. This reduces the risk of rework so that organizations can adapt more quickly to industry change.

• Process Granularity: This emphasizes the design consideration to provide optimal scope and the right level of detail when documenting processes, procedures, and related process elements. It is important to design processes with the right granularity so that end users can easily locate and use necessary materials.

• Process Discoverability: Here the emphasis is on the creation of processes that are discoverable by adding interpretable metadata to increase process reuse and decrease the chance of developing processes that overlap in function. By making processes easily discoverable, this design principle indirectly makes processes more interoperable.

• Process Autonomy: This places emphasis on the creation of processes that carry out their capabilities consistently and reliably in real-world situations. By fostering design characteristics that increase process reliability and behavioral predictability, they are less likely to produce issues that force reactive responses once deployed.

• Process Composability: Here, the emphasis is on the design of elements such as subprocesses in a manner so that they can be reused in multiple processes that are made up of composed elements.

Benefits of Process-Oriented Architecture

There are several benefits to using a POA approach when building Process Ecosystems within an organization. These include

• Increased agility: POA enables organizations to respond quickly to new business imperatives, develop distinctive new capabilities, and leverage existing processes for true responsiveness.

• Reduced maintenance: Maintaining a subprocess or process component as a contained element simplifies the task of maintenance. Changes can be made once and in one place for all business processes that use the component, reducing the effort required to make modifications.

• Reuse of corporate assets: POAs promote the reuse of existing assets, increasing efficiency and reducing process development and improvement costs.

• Streamlined costs: Introduction of POAs within an organization frees up resources and helps to ensure that investments are focused on core capabilities aimed at growing the business instead of on maintenance and modifications to multiple processes.

• Shorter development times: The major benefit of reuse is shorter process development times and reduced development costs. Development times are also compressed because they must conform to a consistent architecture, even though elements from one process can be used in another.

• Maximizing return on investment on legacy processes: As well as providing a level of reuse, joining a legacy process with newer elements created for other processes can prolong its life, allowing an organization to maximize its investment in legacy business processes that cannot easily be thrown away.

• Simplified and productive process development: A unified, easy-to-use set of process attributes and components enhances process productivity, promotes asset reuse, and fosters enterprise collaboration.

• Unified process management and monitoring: A POA that uses shared components and cross-process end-to-end tracking helps provide integrated governance and security.

• Clear and comprehensive view of an organization’s resources: Relationships between people, processes, systems, and goals are easily understood, and changes can be quickly and easily analyzed and implemented.

Process-Oriented Architecture Road Map

Organizations may have several thousand processes with hundreds of subprocesses and related components. The POA road map guides organizations as they progress into a process-oriented operating model and helps them manage the growing number of operational processes that may exist across an enterprise. The POA focuses on delivering the greatest return on investment while ensuring proper process governance is in place. Practitioners can use the POA to build an all-encompassing Process Ecosystem that demonstrates how processes, systems, and other components are aligned. This aids in the identification of organizational enablers and processes that support business success and add value and those processes that do not.

The POA road map is comprised of five steps:

1. Create a POA governance framework.

2. Implement a POA process model.

3. Manage processes.

4. Build an Enterprise Process Ecosystem.

5. Enable the Process-Oriented Enterprise.

The POA assists with meeting the following business objectives:

• Developing and applying governance principles

• Determining how the enterprise environment supports the business strategy

• Identifying operating components that will add value to business processes

• Mapping existing systems, policies, procedures, and other components to business processes

• Setting Process Improvement priorities and assessing the impact of the new processes on the current Process Ecosystem

Creating a POA Governance Framework

Proper architectural governance is crucial when building all-encompassing enterprise Process Ecosystems. Governance ensures all process-related activities are carried out in a planned and authorized manner. This includes ensuring there is a sound business reason behind each process change; identifying the specific processes, people, and systems affected by a proposed change; and ensuring that all changes are executed based on the POA construct and guiding principles. For businesses that are required to comply with the Sarbanes Oxley Act, this is a critical business activity, as section 404 requires that any processes that could affect the company’s bottom-line be auditable. This includes tracking who did what, to what systems, where and when, and ultimately why. Ensuring that an integrated POA governance framework exists enables organizations to implement end-to-end governance across the entire Process Improvement life cycle, thus simplifying how process authors and users discover, reuse, and change processes that effectively deliver on the promise of POA.

There are several subelements within the POA governance framework, including Design Governance, Implementation Governance, and Change Management and Operational Governance. These are discussed below.

Design Governance

Design Governance is an important part of an integrated POA framework that allows organizations to build process solutions according to plan, set priorities, model current and desired processes, and identify and prioritize candidate processes and process changes. Organizations often struggle with balancing long-term planning with the need to address immediate and short-term business requirements. As a result, the short-term requirements often take precedence over long-term strategic planning. When this is applied to enterprise process architecture, organizations often find themselves with several processes that deliver minimal business value and cause confusion and/or duplication.

Proper Design Governance for Process Improvement activities mitigates this issue and facilitates the identification, analysis, and modeling of candidate processes, policies, procedures, profiles, business rules, and other related process information. An effective Design Governance process examines existing processes and planned process improvements to determine which proposed changes should be deployed as new additions to a Process Ecosystem. It also registers reusable process elements to help speed value delivery wherever possible. In this phase of governance, management can assess the relevance and suitability of any proposed change to a Process Ecosystem quickly by using the POA as a reference architecture and source of control over the Process Ecosystem.

Design Governance also ensures that the right individuals within various organizations are coordinated to identify and analyze potential process improvements in a planned and managed fashion. This includes business owners and operators, enterprise architects, business analysts, project managers, process improvement managers, and portfolio managers who have an inherent stake in process work. When utilizing Design Governance mechanisms, processes can be proactively built and released into service as needed. This approach reduces late creation of single-purpose processes and promotes POA goals by avoiding chaotic process sprawl.

Being able to examine the impact of changes to the environment when modifying processes provides an essential service to the company. The more familiar team members are with the Process Ecosystem and its ongoing evolution, the more opportunities arise for improvements in its existing state of operation. The output from the Design Governance process is a set of candidate processes and changes that are inputs to the Implementation Governance process.

An example that illustrates Design Governance in practice is the deployment of a new product line within a company. When launching a new product, an organization must ensure that it can successfully design, build, and deploy the product into the market. Design Governance allows organizations to easily search for and reuse existing processes and components that support the organization’s current infrastructure. In this case, the company is able to reuse and enhance its existing processes, such as its Order Processing process, with new features to handle the new product, rather than creating a new process and potentially duplicating time, effort, and capital.

Implementation Governance

Implementation Governance shepherds approved process changes and additions, as well as any related components, through the Process Improvement life cycle to ensure that the deployment of any proposed solutions is successful. Within Implementation Governance are methods to approve process deployment, ensure policy compliance, maintain adherence to applicable law, drive proper change management, analyze and assess for collusion, and provide clear segregation from other process changes.

In this phase, management can determine if process additions or improvements meet enterprise standards and guidelines before they are launched into an operational state. For example, for a process change to move into business execution, an organization may require that a series of accompanying artifacts and steps be completed in order to authorize the process improvement launch. This could include training and communication, process profiles, process maps, categorization and storage within the enterprise repository, and business endorsement from a process owner for the proposed process improvement. In many cases, Implementation Governance overlaps with Change Management and Operational Governance as process owners and process operators within operational environments respond to feedback about their performance, compliance with corporate strategies, consumer expectations, and feedback from internal team members regarding usability.

Change Management and Operational Governance

Change Management and Operational Governance ensure that processes are behaving correctly and provide a mechanism for absorbing change. When performance gaps are discovered, this oversight ensures that the proposed change actually closes performance gaps with POA guiding principles. Activities within this phase include process monitoring against performance targets and threshold tolerances, impact analysis, and strategic alignment assessment.

The Operational Governance process relies heavily on predefined business rules and business policies to ensure changes made within the Process Ecosystem do not disrupt ongoing business operations. A well-defined Change Management and Operational Governance process will fully detach process consumers and operators from the complexity of process change implementation and enforcement, change management standards, and process training and other nuances or impedances to interoperability. Similar to implementation governance, this phase also includes mechanisms to approve process deployment, ensure policy compliance, maintain adherence to applicable laws, drive proper change management, analyze and assess for collusion, and provide clear segregation from other process changes.

Often new processes are the representation of complex business rules. The mapping of proposed business rules on existing processes can reveal conflicts in business logic long before systems and people are expected to adhere to the new process. There are many cases in which two or more processes conflict and are only discovered postimplementation when proper inspection is not done during change management and operational governance reviews.

In a unified governance environment, processes governed within the Change Management and Operational Governance phase will have progressed through the Planning Governance and Implementation Governance phases. In many cases, organizations will have many existing processes that have not been subject to governance previously; however, it is recommended that they be integrated into POA using this governance framework.

Implementing Process Models

Establishing a common understanding of processes and subprocesses, associated business rules, and other related process components is an important milestone in establishing mature Process Ecosystems. Process Modeling is a technique used to enhance this activity and supports the effort of creating flexible process models that assist organizations in connecting critical process components across the business. The POA Modeling approach is a bottom-up method that consists of assembling integral atomic processes and/or subprocesses and components along with detailed descriptions into one central view. Its purpose is to document and communicate these components and enhance their reuse so that they are better managed and executed.

Process Modeling activity focuses on the practice of constructing process models that adhere to the guiding principles of the POA. These models provide visibility to the inner workings of a Process Ecosystem in order to make them improve and evolve as needed. They enable the development of more robust processes by providing a visual cue that can be used to understand the impact of performance and areas identified for change. As processes evolve, the associated Process Models that illustrate them must also change. New process models often have to be built or existing ones improved as more departments embrace a process-centric mind-set.

There are two key building blocks to implementing a proper POA Process Model:

• Registry and repository: Registries and repositories are built whenever information must be used consistently within an organization or group of organizations. Examples of these situations include organizations that

Transmit information through process- and/or procedure-level activities

Transmit information through process- and/or procedure-level activities Need consistent definitions of process-related information including processes, activities, organizations, and system names

Need consistent definitions of process-related information including processes, activities, organizations, and system names Wish to ensure the accessibility of information across time zones, between databases, between organizations, and/or between processes

Wish to ensure the accessibility of information across time zones, between databases, between organizations, and/or between processes Are attempting to break down silos of information captured within processes and related applications

Are attempting to break down silos of information captured within processes and related applications Suffer from poor collaboration and the communication that shared understanding of interdependencies would reduce

Suffer from poor collaboration and the communication that shared understanding of interdependencies would reduceA Process Registry typically has the following characteristics:

Protected environment where only authorized individuals within an organization are able to steward changes (e.g., a Process Ecosystem Administrator)

Protected environment where only authorized individuals within an organization are able to steward changes (e.g., a Process Ecosystem Administrator) Stored data elements that include both semantics and representations of the process components

Stored data elements that include both semantics and representations of the process components Semantic areas of a Process Registry that contain the description of process elements with precise definitions

Semantic areas of a Process Registry that contain the description of process elements with precise definitions Processes that are represented in a specific format that all operators, users, and managers can understand

Processes that are represented in a specific format that all operators, users, and managers can understand Process Model definitions and structures that have been reviewed and approved by appropriate parties

Process Model definitions and structures that have been reviewed and approved by appropriate parties• Proper asset management: A Process Model requires a definitive library to assist with managing and governing the business and technology assets involved in process creation and improvement. An asset in this context is considered to be any published work product shared or referenced across the organization that meets a recurring business or technical need, is directly related to day-today activities executed by business users, and has a positive economic value to the enterprise.

Assets are useful artifacts for process operators and improvement professionals that, in many cases, help facilitate or directly solve process-related issues if they can be found, used, reused, improved, measured, and governed. Ensuring proper asset management enables organizations to govern and reuse all types of assets, in turn, helping them optimize productivity and resources in their environment.

Regardless of the implementation, the imperative is to adhere to the POA standard of Modeling and link all processes together across the enterprise. It is the inter- and intradependencies between processes and their activities and data elements that help foster productive process improvement discussions. Process models are important as they provide the conduit to attach critical information such as where isolated use of corporate policy, law, compliance, business unit–level decisions/practices, requirements, business logic, work instructions, data sources, application dependencies, security attributes and logically see where each is used. They also act as the source for dynamically rendering points of consideration for effective governance. Consistency in approach and central management are paramount to the ability to harvest value from the investment in a Process Model. Models increase the productivity of process improvement managers and improve the quality of the models they produce, fostering reusability and extensibility within an enterprise Process Ecosystem.

Managing Processes

Process-Oriented Management refers to the practices recommended to keep Process Ecosystems in proper working order. In order to ensure proper maintenance and ongoing sustainability, the POA prescribes seven management practices: Business Management, Life-Cycle Management, POA Enablement, System Management, Compliance and Policy Management, Performance Management, and Semantic Integration. These are described below.

Business Management

Within every growing organization are activities that need to be performed to support process execution and governance. These activities include effective program management to wrap discipline around the quality-of-service targets the business sets out to achieve. This discipline ensures that operating goals are resident within the ecosystem of processes and threads those goals within each independent process, taking special care to reduce complexity and duplication wherever possible. In doing so, visibility of the entire process architecture is maintained. Productivity is increased and speed to value is improved in these cases.

Many organizations establish centers of excellence or departments with the sole purpose of governing their process landscape and its improvements. While this is more prevalent in large corporations where there are designated process officers or process improvement departments, the spirit of the intent can be achieved by grassroots cross-functional teams as well by adopting the constructs presented in this text. Regardless of the staff arrangement, the investment of time and attention toward disciplined management will return dividends. The most critical aspect of effective business management is to push information and decision-support data to flow across processes with transparency to everyone in the organization.

Life-Cycle Management

Process life-cycle management captures the following stages and phases involved in the conception, design, realization, and service of processes:

• Conception: Imagine, specify, plan, and innovate. A process starts to form as one imagines a way to accomplish an end goal and begins to outline a path to meet that goal. The conception phase is often iterative and rapid as it works to move to the next phase. Process conception presents an exciting opportunity to think without constraint about solving complex problems.

• Design: Describe, define, develop, test, analyze, and validate. After an idea is conceived, additional detail and consideration are given to known constraints and facts that result in a clearer design. In this step, information flows begin to be articulated. Simulation, assessment, validation, and optimization tasks are performed in an attempt to build as lean a process as possible with reuse in mind. Proper design at this stage also takes into account the core elements discussed in the Process-Oriented Core Principals: Process Reusability, Granularity, Discoverability, Autonomy, and Composability, as outlined in Figure 4-2.

FIGURE 4-2 Process-Oriented Architecture Guiding Principles

• Realization: Build and deliver. Following the design phase is the realize phase in which the process moves through stages prior to being placed into service. This includes registration of the new process using the governance practices, review by an Architecture Review Board, and establishment of performance monitors/alerts/activities. Many organizations find automation of life-cycle management immensely helpful. There are many tools available that provide rapid prototyping in the design phase and act as a repository for processes such as iGrafx (www.igrafx.com), Aris (www.softwareag.com), and OpenText (www.metastorm.com). Once processes are manufactured, they can be checked against original requirements established in the design phase using computer-aided simulation software. In parallel to these tasks, training and change management documentation work takes place to prepare the organization for the process going into service.

• Service: Use, operate, maintain, support, sustain, phase-out, retire, recycle, and dispose. In the final phase of the life cycle, the focus is on management of service information. In this phase, information regarding the process is published for the user community along with support information needed to operate the process and understand its purpose and availability in order to extract maximum value. A process is maintained regularly in order to ensure that it is still achieving its purpose. Because every process comes to an end, unintended consequences of process retirement must be carefully considered. One benefit of following the POA is the transparency of interdependent processes, data, and outcomes. It is for this purpose that we emphasize the value of process traceability during each phase of process management.

Process-Oriented Architecture Enablement

Process-Oriented Management would not be complete without recognition of the value that enablement methodologies bring to the table. Agile, Total Quality Management, Lean Six Sigma, Business Process Reengineering, and Kaizen are well-documented methodologies that can be used to help organizations tune their processes to yield high quality. Each method is purpose built. Agile is engineered around delivery in an iterative fashion, while Lean Six Sigma eliminates waste from work/processes to achieve no greater than six defects per million opportunities. By extracting the best practices from methodologies such as these, organizations can better manage improvements at all stages of the Process Improvement life cycle.

Systems Management

Systems Management involves management of the information technology systems within the various processes in an enterprise. This includes gathering requirements, procuring equipment and software, distributing it to where it is to be used, configuring it, maintaining it, forming problem-handling processes, and determining whether objectives are being met. As processes become more and more reliable on technology solutions, the most critical element of Systems Management and Design is ensuring that process, not technology, is driving these requirements.

Compliance and Policy Management

Compliance and Policy Management is an organization’s approach to mitigating risk and maintaining adherence to applicable legal and regulatory requirements. The POA framework recommends policy and compliance activities be integrated and aligned within an organization’s Process Ecosystem in order to avoid conflicts and wasteful overlaps and gaps and to ensure proper visibility for all process users and managers.

A common business practice for Compliance and Policy Management is documenting business rules. Business rules are statements that define or control aspects of the business. They assert business structure and influence behavior by specifically describing the operations, definitions, and constraints that apply to an organization. By capturing and centralizing Business Rules within the Process Ecosystem, consistency of rules across process touch points is supported. This also increases visibility of operating practices and enables prompt and comprehensive decisions that comply with law, policy, contract-specific processes, and business unit policies.

The POA focuses on bringing business rules together with processes, subprocesses, and other components and merging them into an integrated, holistic, and organization-wide repository. In applying this approach, organizations can achieve such core benefits as ethically correct behavior, improved workforce efficiency and effectiveness, and improved compliance among the operators who regularly interact and use the processes.

Performance Management

Process-oriented performance management should encompass real-time availability and performance metrics of all processes within the Process Ecosystem, as well as design-time processes for comparison. Established key performance indicators that are attached to individual processes and process collection that aids in identification of processes that are both in and out of control create a competitive advantage. Effective performance management continuously compares the results of in-service processes with those retired and in design to ensure optimized processes are in service.

Semantic Integration

Process consumers and operators must have a shared understanding of the meaning of the various processes within their organization as well as any related components. A common and/or industry-specific vocabulary should be in place, one that includes taxonomies and business semantics for the terms used to describe process artifacts. A standard taxonomy gives stakeholders a common language to use when benchmarking, collaborating, and improving processes.

Building an Enterprise Process Ecosystem

Process Ecosystem is a term used to specify the processes in an organization that are directly involved in adding value to the company as well as their related components and supporting activities. These processes can be connected to each other in sequence, can be atomic, or can be composed of other subprocesses. Processes also contain several important attributes that can be added to form an all-encompassing repository of business information. Enterprise ecosystems identify all the processes that are interconnected and driving toward business success. Two fundamental architecture concepts, in addition to creation, are used to build a Process Ecosystem within the POA construct: Orchestration and Choreography.

Process Orchestration is the coordination and arrangement of multiple processes or subprocesses exposed as a single aggregate process. Process Improvement professionals apply Process Orchestration to design and improve processes using existing process components within an organization. In other words, Process Orchestration is the combination of multiple process interactions to create higher-level business processes. With Orchestration, the process is always controlled from the perspective of one business organization.

Process Choreography is more collaborative in nature, whereby several processes are sequenced to run in connection with one another; these processes may involve multiple parties and multiple organizations. Process Improvement professionals utilize Process Choreography to design and improve processes in an organized manner across multiple organizations. With Choreography, the process is usually controlled from the perspective of multiple business units.

As illustrated in Figure 4-3, a Process Ecosystem should be thought of as multiple processes that are interconnected and related to their environmental conditions. Ever changing, adapting, and serving an individual and collective purpose, the ecosystem must also have sufficient maintenance to remain in good health.

FIGURE 4-3 Process Ecosystem Overview

The Enterprise Process Ecosystem is a clear recognition of existing interconnections between processes. Successful businesses recognize the choreography and orchestration needed to organize the essential activities within a process or subprocess, as well as the order and conditions that drive when to trigger a process to be initiated and completed. This forms dependent and interdependent understanding and, when placed into the POA framework, illuminates all players’ roles within the ecosystem.

The ecosystem’s health can be maintained by employing strategies that include having clarity about the purpose of each process; ensuring process requirements and intended value and the rules that govern them; determining what resources are engaged in supporting them; identifying the risks and thresholds that need to be in place in order to be responsive; using the scenarios and cases/situations that the process should be triggered on, as well as what subprocesses and procedures they spawn. Monitoring the Process Ecosystem requires putting in place measures that report targets and threshold zones as close to real time as possible. Often, performance dashboards aid process workers in understanding where bottlenecks are occurring. This enables intelligent inspection and resolution. Without the enterprise Process Ecosystem perspective, bottlenecks can be misunderstood and valuable time and resources can diminish the value of the project simply due to a lack of visibility of more serious problems elsewhere.

Enabling the Process-Oriented Enterprise

Every organization has processes that are used with varying degrees of efficiency within the context of a department or suborganization. A Process-Oriented Enterprise seeks to incorporate the extension of a standardized process across the entire organization and distribute, or federate, processes in a gapless fashion.

Process Federation is the capability to aggregate and leverage process-related information across multiple sources into a single view. This allows companies to reuse shared components. In essence, it is the act of federating, or joining, process components, departments, and users into a unified federation. This enables independent groups to establish a trusting relationship that encourages the sharing of capabilities.

Process Federation can be very challenging for many organizations. It requires significant understanding of an organization’s entire business model, strong abstraction skills for those engaged in governance and process design, discipline, and conformity with the standards presented in the POA. It takes a high degree of discipline to achieve full federation. The complexity involved in designing processes for federation can be taxing too as the pressures of speed to value and individual departments challenge the value of federation to the core. This is especially apparent as the number of processes increases within the ecosystem. During these times, it is even more important to follow the framework in order to achieve the higher-order goals of a process-oriented enterprise.

Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we reviewed the definition of POA and its position as a core knowledge area within The Process Improvement Handbook. It provides a means to manage and understand change and describes how to use change as a strategic advantage and how to successfully install Process Ecosystems within an organization. Although it requires investment and maintenance, it yields a very definite return. From this chapter, we also identified the following key principles:

• There are six core principles of a POA: Loose Coupling, Process Reusability, Process Granularity, Process Discoverability, Process Autonomy, and Process Composability.

• POA enables organizations to respond quickly to new business imperatives, develop distinctive new capabilities, and leverage existing processes for true responsiveness.

• The POA road map guides organizations as they progress into a Process-Oriented operating model and is composed of the following five parts:

Creating a POA Governance Framework

Creating a POA Governance Framework Implementing a POA Process Model

Implementing a POA Process Model Managing processes

Managing processes Building an Enterprise Process Ecosystem

Building an Enterprise Process Ecosystem Enabling the Process-Oriented Enterprise

Enabling the Process-Oriented Enterprise• Process Ecosystem is a term used to specify all processes in an organization as well as any related attributes that are directly involved in adding value to the company.

• Process Orchestration is the coordination and arrangement of multiple processes exposed as a single aggregate process.

• Process Choreography occurs when several processes are sequenced to run in connection with one another and may involve multiple parties and multiple organizations.

• Process Federation is the capability to aggregate and leverage process-related information across multiple sources into a single view.

Chapter Preview

We have covered the key terms used in Process Improvement environments, the importance of Process maturity, as well as the need to properly architect all processes within an organization. Chapter 5 discusses the use of the architecture principles found in the POA to construct an Enterprise Process Ecosystem.

Transmit information through process- and/or procedure-level activities

Transmit information through process- and/or procedure-level activities Need consistent definitions of process-related information including processes, activities, organizations, and system names

Need consistent definitions of process-related information including processes, activities, organizations, and system names Wish to ensure the accessibility of information across time zones, between databases, between organizations, and/or between processes

Wish to ensure the accessibility of information across time zones, between databases, between organizations, and/or between processes Are attempting to break down silos of information captured within processes and related applications

Are attempting to break down silos of information captured within processes and related applications Suffer from poor collaboration and the communication that shared understanding of interdependencies would reduce

Suffer from poor collaboration and the communication that shared understanding of interdependencies would reduce Protected environment where only authorized individuals within an organization are able to steward changes (e.g., a Process Ecosystem Administrator)

Protected environment where only authorized individuals within an organization are able to steward changes (e.g., a Process Ecosystem Administrator) Stored data elements that include both semantics and representations of the process components

Stored data elements that include both semantics and representations of the process components Semantic areas of a Process Registry that contain the description of process elements with precise definitions

Semantic areas of a Process Registry that contain the description of process elements with precise definitions Processes that are represented in a specific format that all operators, users, and managers can understand

Processes that are represented in a specific format that all operators, users, and managers can understand Process Model definitions and structures that have been reviewed and approved by appropriate parties

Process Model definitions and structures that have been reviewed and approved by appropriate parties

Creating a POA Governance Framework

Creating a POA Governance Framework Implementing a POA Process Model

Implementing a POA Process Model Managing processes

Managing processes Building an Enterprise Process Ecosystem

Building an Enterprise Process Ecosystem Enabling the Process-Oriented Enterprise

Enabling the Process-Oriented Enterprise